ABSTRACT

This article outlines some of the key cultural shifts that influenced moviegoing for girls and women in British Malaya. To reconstruct the patterns of film exhibition during the silent and early sound era, it draws on archival resources, including American trade press, local popular press, and oral interviews with elderly Singaporeans; these were conducted in the 1980s, by the Singapore National Archives, when spectators who experienced silent moviegoing were still alive. Methodologically, this work draws on feminist film scholarship that focuses on the socio-cultural role of cinematic consumption at a defined, historical moment. The article contextualises cinemagoing within a wider framework of spatial geographies under colonial rule. It also interrogates the popularity of Hollywood on the national screens, and the related, gendered anxieties on moviegoing expressed across the Malayan public sphere.

Introduction

The last decade has seen an increased interest in the social, economic, and gendered aspects of cinemagoing in the past; the dynamic field of study referred to, especially in European academia, as New Cinema History.Footnote1 Scholars working on the American context, such as Shelley Stamp, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, and Diana W. Anselmo, made tremendous strides in bringing the experiences of silent film audiences to the forefront of film history, the discipline which has been dominated—until the early 2000s—by the historiographies of authorship and textual qualities of specific films.Footnote2 Yet, the developments in histories of cinematic distribution and consumption outside of the hegemonic paradigm of Europe and North America, and specifically into Southeast Asia, remain vastly overlooked. The insightful articles by Dafna Ruppin and Nadi Tofighian constitute a notably rare exception.Footnote3 This work aims to sketch some of the empirical parameters of moviegoing in the silent, as well as early sound era in British Malaya, by drawing on film advertising, oral histories conducted in the 1980s by the Singapore National Archives, and other fragmentary traces of fan practices that emerged from the popular press of the era.

Both Anselmo and Stewart focus on a marginalised viewership—Anglo-American girlhood and African Americanness respectively—which forces them to engage with fiction writing or scrapbooks; primary sources not favoured by the historical protocol.Footnote4 Unlike the opinion pieces written by middle-class, male, and usually white journalists, girls’ attachment to cinema rarely left an imprint on the archive. If women’s stories are ephemeral, then we need to start ‘miscellaneous acts of collection’ to unearth them.Footnote5 As Kathryn Fuller-Seeley observes, we can never have more than a partial understanding of the practices of fans removed from us by a century; such fleeting glimpses can be, nonetheless, ‘valuable and fascinating.’Footnote6

Capitalising on these feminist approaches, this study opens with a discussion of Dulcie Mable Foston, an avid moviegoer from Singapore whose name was published in American monthly Motion Picture Magazine in 1919. Dulcie was seventeen years old at the time. Starting with an individual, the article aims to shed light larger issues of gender, race, and class, that impacted Malayan public life. As a microhistory, it searches ‘for answers to large questions in small spaces,’Footnote7 diversifying silent film historiographies. It also emphasises the agency of historical actors whose impact is often diminished. Then, it moves on to examine the key cultural dynamics that influenced Dulcie’s experience of the movies during her girlhood and twenties: outlining the patterns of exhibition in her hometown, and the popularity of Hollywood fare. Through the process of ‘reconnecting film texts to specific contexts of exhibition and reception,’Footnote8 it aims to illuminate the opportunities—and constraints—inscribed in public leisure for young women. Lastly, it delves into the gendered anxieties on moviegoing expressed across the Malayan public sphere.

Dulcie Mable Foston

Dulcie Mable Foston could not wait to get her hands on the newest issue of Motion Picture Magazine. The title was her favourite for a while now; she always looked forward to her monthly dose of celebrity gossip, fashion advice and film reviews. At $3 for a yearly subscription, it was not cheap, but as far as she was concerned, it was well worth it.Footnote9 She was nearly 9000 miles away from Hollywood, yet, the glossy pages packed with stories of stars and glamour, made her feel as if the global film capital was only a stone’s throw away. This time, however, she was getting particularly impatient.

‘You should not get your hopes up,’ her mother might have told her, knowing all too well the odds were not in her favour. Dulcie was charming, no doubt, but was she really star material? Luckily, Mrs Folston was not right; not this time at least. Dulcie gasped as she saw her name next to the photographs of other young women selected for the popular Fame and Fortune contest.Footnote10 Still, the posed studio photograph she submitted for the competition was nowhere to be seen; her presence on the page was limited to name and name only. Why? The reasons behind this move are unclear—did the editors deem her to look too Asian, and therefore not fit for the contests? After all, one of the explicit reasons behind such ventures was to extol the virtues of white femininity. The titular promise of fame and fortune was extended to white women, and white women only.

Dulcie was only a month shy of seventeen when her name was featured in the Fame and Fortune contest in May 1919. The editors of Motion Picture Magazine received an astonishing 4000 photographs from readers each month, so the competition was intense.Footnote11 Despite her young age, she was no stranger to the spotlight, having danced and sang at local events.Footnote12 At the time, she lived at 19 Seah Im Road, Keppel Harbor, Singapore, most likely with her mother, two sisters, Gwendoline (or Gweneth), and Mavis, and a brother named Colin. She was the youngest of four. Although she might not have looked like it, with her somewhat light complexion, she was Singapore born and bred. In fact, her family had been living in the rapidly growing metropolis for at least two generations. The census records classified the girl’s mother as Eurasian. Her maternal great-grandfather arrived in the first half of the nineteenth century from Sumatra, when Singapore—nicknamed ‘Sin-galore’—was still a relatively small, crime-ridden port town. Dulcie’s father, who died when she was less than two years old, hailed from Chennai, India.Footnote13 Although her mother re-married in 1912, she became a widow, again, only a year later. While it is difficult to know how the family managed their finances, or whether they received inheritance after the passing of Dulcie’s stepfather, it is possible they were supported by extended family members. Two of Dulcie’s uncles were doctors for the Malayan Medical Service, suggesting a middle-class standing.Footnote14

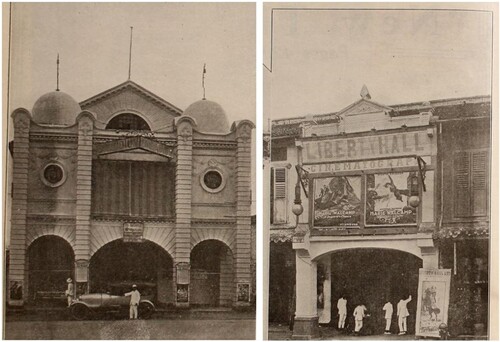

I take Dulcie’s story as an entry point for a wider exploration of urban moviegoing across the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States; separate administrative entities known conjointly as British Malaya. Dulcie’s birth in 1902 coincided with the rapid popularisation of photoplays as public amusement. The medium came to Singapore in May 1897, less than two years after the Lumiére brothers showcased the technology to a Parisian audience.Footnote15 It took place in the hall adjacent to Adelphi Hotel, on Coleman Street (). This testifies to the speed with which film circulated in the region. This was no backwater outpost, but a place at the very centre of transitional, modern developments.

Figure 1. Adelphi Hotel, Singapore, in the mid-1920s. Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Pacific Pursuits: Postcards, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Gelatin silver print.

Those living in peninsular hinterland, and outside of metropolitan areas, were no strangers to moving pictures either. Indeed, Ruppin and Tofighian postulate that, ‘several different cinematographic companies and devices’Footnote16 were present in Southeast Asia around fin de siècle. Travelling companies moved from one Malayan town to the next, showcasing the wonders of the cinematograph to enthusiastic crowds of men, women, and children. Screenings of the 1900s tended to take place in tents made of canvas and bamboo, erected specifically for that purpose, and taken down after a few months.Footnote17 At least three permanent cinemas open in Singapore during the 1900s.

In terms of her ethnic makeup—with an Anglo-Indian or Indian father, and Eurasian mother—Dulcie was hardly representative of the city’s movie-struck girls. Alexius Pereira indicates that ‘despite discrimination from the Europeans’ Eurasians held considerable privilege over Asians.Footnote18 Then as now, most Singaporeans were of Chinese heritage, with Europeans and Eurasians accounting for only two and one per cent of the local population, respectively.Footnote19 But the statistic fails to adequately capture the nature of Singapore as an interconnected, plural capital. By the dawn of the twentieth century its residents represented no less than fifty-two different nations.Footnote20 Other historians illustrate how global port cities of the Malayan archipelago were at the epicentre of the tectonic shifts caused by the forces of consumer capitalism, and rise of communication technologies. Like other outposts of the empire, Singapore was ‘tied loosely to a network of local, diasporic, national and imperial affiliations that made them impossible to define through any one homogenizing concept of race or nation.’Footnote21

Arguably, as being both Eurasian and middle-class, Dulcie and her family occupied higher echelons of society. As such, she is more of an exceptional, rather than an ordinary case study. But her value for this historical investigation lies somewhere else. Looking at individual movie fans is useful because their experiences move us away from an erroneous notion of historical spectatorship as a monolith. Here, I draw on works by brilliant feminist scholars—namely Stamp, Annie Fee, and Anselmo—to uncover the meaning of cinema to girls and young women at a specific, historical moment.Footnote22 I aim to unpack some of the dynamics that structured the attractions, and dangers, of moviegoing. It is an act of interweaving cinemagoing into the rich tapestry of Malayan modernity. By contrasting the narratives emerging from various communities, this article demonstrates how historical practices are invariably gendered, but also how femininity intersects with other elements of identity, generating unique experiences.

By 1920, in her late teenage years, Dulcie could choose to attend one of at least eight movie houses: Harima Hall, Palladium, Gaiety Theatre, Liberty Hall, Arcadia, the Empire, the Marlborough and Alhambra ().Footnote23 Because the last two were located on the beachfront, just next to each other, they were commonly referred to simply as hai kee, meaning ‘by the sea.’Footnote24 Some locals who patronised Alhambra in the 1930s had vivid memories of the sounds of waves crushing in high tide, as the movie plots unfolded onscreen.Footnote25 Indeed, it is easy to imagine Dulcie having similar experiences, hearing the murmur of the sea as she marvelled at the daring adventures of the serial heroine Beverly Clarke in The Great Secret (1917).Footnote26 What emerges from the oral histories of the era is that many parents preferred to escort their children to the movies, or at least delegate a grandparent or aunt to join them.Footnote27 Being the youngest of five children, Dulcie could have gone to the shows with one of her siblings, or one of many members of her extended family.

Mapping urban segregation

Before delving further into cinemagoing and its meanings, it is necessary to sketch colonial dynamics that permeated structures of Malaya, geographically and ideologically speaking. After all, histories of spectatorship rest upon ‘the specific situation of viewing.’Footnote28 These viewings, in turn, have tangible foundations, organised spatially within the city and its communities. While the society in which Dulcie operated was incredibly diverse, it was far from egalitarian. Inequalities were inscribed in the patterns of urban planning all over Malaya, as colonial governments allocated Malays, Chinese and Indians separate residential districts.Footnote29 Needless to say, the areas seen as the most desirable were reserved for the exclusive use of Europeans.

Furthermore, the regime used explicitly racist logic to rule over its subjects. Colonial administrator Frank Swettenham famously commanded the entrepreneurial, hard-working spirit of the Straits Chinese, contrasting them to Malays, whom he viewed as superstitious, lazy, and vengeful.Footnote30 Ideas of racial inferiority reduced them to a lower stratum of society. British officials succeeded in constructing strong occupational and, by proxy, economic divides between specific ethnic groups in the territory. This is the reason why colonial modernity can be a slippery term, ‘an uneven and heterogeneous thing to which different racial and socioeconomic groups had uneven claims.’Footnote31 The level of segregation—prevalent when it came to housing—was also replicated, to some degree, in the practices of leisure. Nadi Tofighian clarifies that racially exclusive social clubs were prevalent amongst the white elites. In excluding Asians, these gatherings worked to create a sense of allegiance amongst European diaspora, further solidifying British power.Footnote32

The presence of structural racism is what, paradoxically, makes silent moviegoing such an interesting phenomenon. Scholars indicate that spectatorial practices in the early film period in Southeast Asia were fragmented, but also how that fragmentation was not dictated by race alone. Through her analysis of cinema as a social institution in Dutch-ruled Java, Ruppin shows that auditoria were partitioned into three or four segments, each representing a different price range.Footnote33 Although the cheapest sections were marked clearly as ‘Natives only,’ others were ‘potentially available to all members of colonial society,’Footnote34 as long as they were able to afford the fee.

Tofighian uncovers evidence of paralleled practices at a cinematograph show in Kuala Lumpur in 1906.Footnote35 Affluent Chinese women sat side by side their European counterparts, obscuring ethnic divides, yet levelling those of class. James Burns comes to a similar conclusion, writing that cinemas in Malaya were divided across economic, rather than ethnic lines. Thus, they ‘proved to be one of the few public places where colonizers and colonized mixed (…).’Footnote36 In the following decade, Singapore’s consul general described ‘the cinematograph show’ as a highly diverse site, populated by Malays and Chinese alike.Footnote37 An American trade publication added that ‘Europeans always sit in the best seats, but the natives make about 85 per cent of the patronage of the theatres.’Footnote38 While Western reports on British colonies are informed by racial prejudice, and need to be taken with a grain of salt, it appears that spatial arrangements were informed by economic status, and that such categories could be, at times, transgressed. In other words, it was money, and not skin colour alone, which dictated who sat where.

Many historical studies emphasise the fact that the urban expansion of the 1920s offered opportunities to rupture the boundaries of racial division so persistent to rural life. Historian Lynn Hollen Lees maintains that ‘commercial entertainment and mass culture worked to bridge and, consequently, to lower the boundaries of ethnic differentness. By the 1930s, the towns of British Malaya had drawn many of their inhabitants into a culturally hybridized, transnational commercial culture.’Footnote39 Despite separating different groups of citizens, the darkened space of the theatre enabled some intermingling. Contemporary film advertising supports this view. Take, for instance, the promotional material circulated by the managers of Singapore’s Gaiety theatre—at the junction of Albert and Bencoolen Street—which appeared simultaneously in Chinese, Malay, and English-language outlets.Footnote40 Even in a smaller township of Ipoh, managers used film posters that included text in several languages.Footnote41

As commercial film venues flourished, they started to distinguish between the well-to-do and the general public, concentrating on one segment of their audience. With her conspicuously white looks, Dulcie was a beneficiary of this unjust system. It is probable that Dulcie did not visit Alhambra too often; after all, the Beach Road was four miles away from her family home. Car ownership was rare, so as most Singaporeans she would have relied on cycling, rickshaws, and so-called mosquito buses to get around. She might have attended high-brow establishments, like the Palladium, where she would have been surrounded by a handful of Europeans as well as affluent Chinese patrons. On such occasions, Dulcie might have been joined by one of her cousins, who lived in a tight-knit Eurasian enclave on Selegie Road, near metropolitan amusements.Footnote42 One of the city’s earliest movie palaces, Palladium promoted itself as ‘house of refinement’ catering to the ‘select few.’Footnote43 Perusing contemporary Anglophone press, one comes across numerous and rather explicit references to the class of its patrons. In praising its offerings in 1923, Malaya Tribune described Palladium as ‘the rendezvous of Society.’Footnote44 Interestingly, while Palladium was owned by a Chinese entrepreneur Tan Cheng Kee, its customer-facing management remained white.Footnote45 In the oral history conducted by the National Archives of Singapore, an ethnically Chinese woman remembered that, in the 1930s, Palladium’s balcony seats were off-limits to everyone but Europeans.Footnote46 If this was the case, then perhaps Dulcie was able to capitalise on the privilege that came with passing for white.

Hollywood influence

The fact that Dulcie was invested in American film culture, represented here by her interest in Motion Picture Magazine, underlines the importance of Hollywood as a transnational product during the late 1910s and beyond. The dominance of American narratives on screens of Malaya and the Straits Settlements is undeniable: in 1935, Film Daily Yearbook estimated that out of all the features distributed in the region, seventy-two per cent came from the United States; a further fourteen per cent were, unsurprisingly, British productions.Footnote47 Earlier breakdowns, however, point to a significant portion of films—as many as nineteen-per cent—being imports from mainland China.Footnote48 For the urbanites of Singapore, Penang, and Kuala Lumpur, moviegoing was synonymous with American movies. Decades later, many retained fond memories of watching Westerns and action serials, listing Hoot Gibson, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd amongst personal favourites.Footnote49 To step into the theatre, then, meant to step into the realities of other, distant lands.

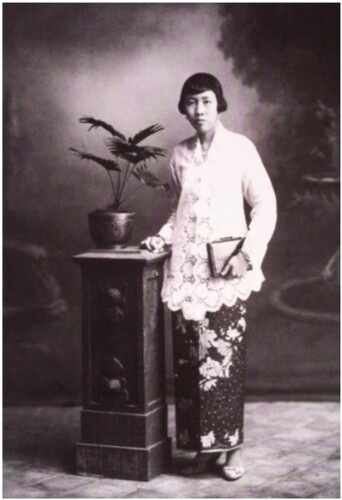

Most colonial subjects had no personal relationships with whites, who constituted an enclosed, elite circle.Footnote50 Movies were a key avenue through which they had familiarised themselves with conspicuous consumption. It was especially through screen stars—with permed hair and lavish gowns—that modern Malayans had learnt about, and often embraced, Western ideals of fashion and beauty.Footnote51 Betty Guat Beng Seow, who was born in 1910, made similar observations. ‘Dress, going out, speaking (…) I mean … they get western ideas from the movies,’ she explained, reflecting on the influence of cinema on her peers back in her teenage years.Footnote52 Consequently, discourses on cinema and its hazards could not be separated from wider debates on Westernisation and its impact on the local youth. ‘Younger Chinese, Eurasian, and Sinhalese women,’ Hollen Lees (2017, 240) suggests, ‘bobbed their hair and sometimes wore European-style frocks.’Footnote53

Numerous scholars established that the desire to imitate stars was a common feature in testimonies on moviegoing shared by the elderly.Footnote54 In terms of film fashion and consumerism in the UK, Annette Kuhn summarises that female cinemagoers could ‘buy, they could improvise, or they could go without.Footnote55 Of these, improvisation appears to have been the favoured strategy.’ Girls took inspiration from screen hairstyles because it did not require the spending that a Hollywood-worthy wardrobe would incur. A star-inspired haircut was much more attainable than a star-inspired dress.

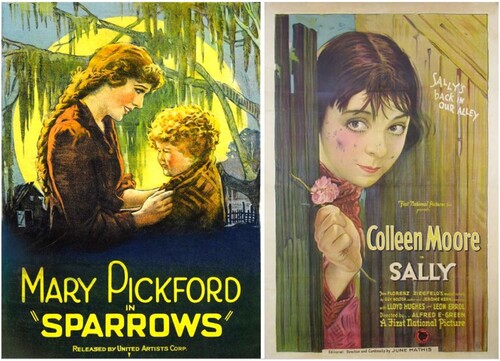

Indeed, similar tactics were popular amongst film fans in Malaya. In a biography published in the early 1990s, a Chinese Malaysian Betty Lim remembered cutting her hair short in her youth. The decision was influenced by her soon-to-be husband, who persuaded her to emulate the style of Colleen Moore, an actor he admired ().Footnote56 The girl’s parents did not approve of such a drastic change. Her fiancé was, of course, delighted. In embodying a popular screen idol, Lim was not only rebelling against parental expectation; she was also expressing what she aspired to be, giving free rein to her sexual agency and power. Interestingly, movie actresses became a shorthand for specific haircuts in parts of East Asia during the 1930s. In Japan, a short bob took its name from Louise Brooks, who set the trend.Footnote57 Historian of Japanese culture Lois Barnett highlighted the correlation between Westernised appearance and forming new, more autonomous identities for the country’s women.Footnote58 Malaya Tribune noted that modern girls of Japan wore their hair in Hollywood fashions, modelling their sartorial choices after Joan Crawford, Key Francis, and Carole Lombard.Footnote59

Figure 3. (a) and (b). Sparrows (1926) was exhibited in Singapore in early 1927, causing some controversy. Sally (1925) starring Colleen Moore screened at Singapore’s Victoria Theatre in July 1927. ‘The Cinema Bill,’ Malaya Tribune, 13 October, 1927, 8.

The relationship between Hollywood and glamour was eagerly reinforced by the Malayan press. One column from the Strait Times—likely a re-print of a more general release from the American film studio—informed the readers of the beauty secrets of the most sought-after movie personalities. Pola Negri advises women not to sleep late; Norma Talmadge focuses on beautiful hair in cultivating attractiveness. Marion Davies believes beauty can be maintained with outdoor activity, as well as ‘plenty of soap and water.’Footnote60

This is not to say that young women of Malaya were unanimous and uncritical in adopting Western mores; far from it. Even if the popular discourse painted film spectators as passive observers, fully absorbed in the on-screen message, numerous film historians have since theorised how silent film audiences made sense of photoplays in their own, distinctive ways, depending on their lived experience.Footnote61 Academics theorised ‘colonial mimicry’ as much more than an act of straight-forward reproduction of habits associated with white agents.Footnote62 Mechanisms of imitation are performative and self-aware. Firstly, audiences that flock to cinemas are seldom, if ever, taking movies at face value. Rather, they use their lived realities to make sense of what they see onscreen, actively adapting, appropriating, and re-fashioning desirable aspects of film culture. In her fascinating study on educational films in British Malaya, Nadine Chan illustrates how films were often received ‘in ways loosened from their original intent.’Footnote63 Being a yield of white hegemony, Hollywood favours American, imperial values. Emotional responses to film are multifaceted, and—especially in the case of marginalised groups—are fraught with contradictions. These political processes naturally complicate spectatorial pleasures for Asian viewers, who are faced with a series of ideological and representational dilemmas. This positionality, both fascinating and complex, is worth mentioning, even if it falls outside of the purview of this piece.

Secondly, and of equal importance, is the increasingly global context in which moviegoers experienced the movies. Port cities, including Penang and Singapore, were characterised by a bewildering level of syncretism. These were vibrant, cosmopolitan arenas that had welcomed cultural convergence for centuries. While modern girls imitated movie costumes by wearing shorter skirts and long beaded necklaces, they continued to draw on local modes of dress, such as sarong kebaya (). Their clothes attested to fusion and hybridisation. Su Lin Lewis determines that during the Jazz Age, traditional Malay garments gained new patterns—cowboys and palm trees—encapsulating Hollywood inspirations.Footnote64 Young fashionistas also looked to other Asian traditions for inspiration.Footnote65 An article in Straits Echo commended Peranakan women for their unique sense of style:

She wears the comfortable Chinese coat and trousers `a la Canton, but the next moment she is ready to slip into the “sarong” and “kebaya.” She can be as much at home with the tight-fitting Shanghai “cheong sum” as she is with the European skirt. She presents a mixture of styles and fashions of different places and periods.Footnote66

Hazards of cinemagoing in the press

A considerable body of literature investigates the fertile ground between film and print culture in the United States during the first three decades of the twentieth century.Footnote67 The local press is an invaluable source for the film historian, not only because it featured cinema adverts, but also because it created a space in which individuals could deliberate the pleasures and pitfalls of the movies. Readers kept abreast of debates on film culture, discussing the conditions of moviegoing, praising their favourite actors, or scrutinising film content. Similar polemics emerged in the Malay setting although, as one would expect, were compounded by distinctively local considerations. To map the intersections between film and Malayan print culture we need to acknowledge it as, to some degree elitist. During the first two decades of the twentieth century printed materials remained expensive, and as such, most periodicals made no attempt to cater to a broad section of society. Low accessibility of texts was compounded by literacy rates, which remained low outside of the most privileged, middle-classes of Europeans, Peranakan Chinese, and urban-dwelling Malays.Footnote68

In her study of the Anglophone Asian public sphere in 1930s Singapore, Ai Lin Chua chartered a series of lively discussions, where editors and keen readers wrestled with the harmful influence of the movies.Footnote69 Elsewhere, she asserted that the Malaya Tribune, a bestselling daily in the country by mid-1930s, catered predominantly to Asian intelligentsia instead of the white elite.Footnote70 Mark Emmanuel highlights the highly interactive role of periodicals in the era; opinion pieces and reader letters constituted such a substantial part of their coverage that he calls them ‘viewspapers’ rather than newspapers.Footnote71

The idea that cinema introduced youngsters to inappropriate content was a vested topic. A reader of New Strait Times advised fellow moviegoers to exercise caution when going to the pictures with children. Sparrows (1926) starring Pickford was, in his mind, too violent and ‘depressing’ to be suitable for them:

Adults can watch this morbid nonsense and treat it as such, but anyone who doubts the importance of placing such a spectacle before children should cast his mind back to his childhood days and recollect how easily his mind received impressions of the wrong kind. The general atmosphere of this picture is one of misery and ill-treatment.Footnote72

The sickly sentiment [of American films] appeals to romantic young girls, and the spurious chivalry to callow youth. But all unbeknown to them, the insidious poison saps their moral foundations. A single visit to a cinema has ruined many an innocent girl or boy (…) To-day [sic] boys and girls learn their fashions and pick up their morals from “stars” of Hollywood. What a shame!Footnote74

Hazards of cinemagoing were combined with other issues on the pages of the vernacular press. Contributors writing for a Malay-language magazine Saudara had strong opinions on urban modernity, of which cinemagoing was a key element. Debates on the growing independence of women captured Saudara’s interest with particular force, as it presumably threatened the unity of ethnic Malays. As one would expect from a publication based on the principles of Islamic reform, shifting social patterns were met with suspicion, if not outright criticism. At the same time, Saudara’s revenue relied on adverts for various goods and commercial spaces—cinemas, record labels and dance halls—that were not aligned with a conservative Muslim worldview.Footnote76 One column stated that Muslim women were becoming more and more indecent because all their desires were indulged; English-educated girls were free to sport foreign fashions, and ‘allowed to go to cinema and other centres of leisure in the evenings.’Footnote77 This situation was blamed on Malay men, who did not exert enough control over female family members, so they were free to do as they pleased. Therefore, gender compounded the perception of some of these threats. Various agencies—be it the government, cinema operators, or families—were seen as responsible for guarding women against corrosion related to mass consumer culture. Left to their own devices, they were bound to go astray.

In many ways, playhouses encapsulated the most dreaded aspects of modern living. They stood in opposition to religious values; these were spaces where, as another letter to Saudara asserted, both genders intermixed late into the night.Footnote78 Rooted in these conversations was a sense that women’s participation in commercial recreation is almost universally an act of transgression. It is not the ideology propagated by the movies that causes a problem, but the settings in which the screenings take place. This is not to say that such concerns were unique to the Malay discourse. Far from it. Readers of the Anglophone press often suggested that movies are detrimental to young people’s emotional growth, regardless of their content. It was the spatial organisation of the screenings that was met with reservations. One concerned Singaporean reasoned that movie halls, which screened pictures late into the evening, were quickly becoming a refuge for the ‘juvenile vagrants.’Footnote79 Recreational facilities where youngsters could witness the wonders of nature, such as parks and aquariums, were infinitely more wholesome than ‘the streets and the cinemas,’ places that another contemporary observer understood to be ‘full of poison.’Footnote80

Criticism of this kind was expressed in other parts of the globe during the earlier decades, chiefly in the 1910s and 1920s. Questions regarding cinema, cheap sensationalism, and corruption, made their way into the public realm in other countries of the region. In Bangkok, another Southeast Asian metropolis, the advent of cinemas permitted middle- and working-class women to interact with men; a fact featured in popular literature of the period.Footnote81 Jasmine Nadua Trice posits that conversations around movie theatres as unruly spaces were common in the Philippines throughout the 1920s.Footnote82 Stamp uncovered the ways in which American journalists cast a shadow of moral degradation on women embracing cinemagoing.Footnote83 Moving picture theatres were dangerous precisely because of their material qualities; because they tempted unmarried women to engage in ‘untoward’ romantic conduct. Much of this reasoning sought to regulate girls’ mobility, or remove them from the public sphere altogether. Confining women to domesticity, or monitoring their activities outside of it, was a preferred solution.

In Malaya, the belief that movie halls were perilous sites was closely associated with the appearance of more relaxed modes of courtship. A growing number of Malayans was defying traditional, patriarchal mores by choosing love marriages over arranged marriages of their parents. Both crowded and darkened, cinemas provided, to borrow Stamp’s turn of phrase, ‘a measure of privacy and anonymity beneficial to romantic encounters.’Footnote84 Or so it was feared. In 1931, an article in the Malaya Tribune quoted Mr. Ong Eng Lian, who cautioned against giving too much freedom to young Asian women, traditionally brough up with ‘a certain amount of restriction.’ To lift these restrictions meant to put their reputation, and subsequent value in the patriarchal system, at stake. He described the habits of the local-born modern girl as follows:

Those girls met their young men, who were perhaps not introduced to the family, at a cinema. The $1 seats were not good enough for them. They were up-to-date girls and they must go upstairs. After the cinema they went for a “bite” and after that to one of those favourite parts of Singapore for a dance. And to be up-to-date those girls took an alcoholic drink and danced the fox-trot.Footnote85

Although all movie-struck girls had to negotiate their way through patriarchal assumptions, some were afforded more independence than others. Keong Poh Chan was twelve years old at the outset of the 1930s. She remembered the decade as a time when all social outings with her peers had to be chaperoned, even though her father had relatively liberal views on the societal role of women. Chan also added that going to the movies was, alongside playing badminton, one of the few instances when a girl like herself could socialise with boys.Footnote88 Her memories reflect a social reality in which cinemagoing in larger mixed groups was increasingly normalised.

Urban habits need to be read in conjunction with religious sensibilities and traditional expectations, which naturally varied from one ethnic group to the next. At the same time, Lewis’ scholarship on Penang complicates this rather insular view, positing that various citizens of Malaya observed and learnt from each other. ‘Generally,’ she writes, ‘the Straits-Chinese and Eurasians were seen as more liberal, providing a model which some Indian, Sinhalese and other communities sought to emulate to modernise themselves.’Footnote89 Even within a given community, different people had different takes on how to raise their daughters.

Young women of European backgrounds were not subject to the same level of regulations upheld, for instance, by Peranakan families. It is possible that Dulcie, who was raised in accordance with Anglican values, could navigate the city with relative ease, at least when contrasted to girls of Malay, or even Straits-Chinese heritage. Still, it is difficult to assume the level of parental pressure she would have experienced based on religion and ethnicity alone. One of Dulcie’s younger cousins, Ronald Milne, described the weekly routines of his teenage years by recalling that he would meet with a large group of friends and neighbours on most Fridays, and head to the open-air cinema on Singapore’s Boundary Road.Footnote90 He also noted that the group was ethnically exclusive, but not limited to one gender. Another Eurasian, Noel Arthur Pereira, elaborated on the courtship rituals he engaged in during the 1930s. Most of the time, he participated in picnics, dances and cinemagoing as part of a larger group. When meeting his girlfriend in the city, he was not chaperoned.Footnote91

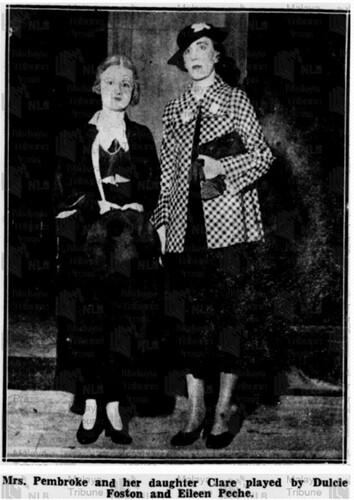

Now, I want to bring my attention back to Dulcie Foston, whose entry into Fame and Fortune competition opens this article. Dulcie grew up with movies in the most literal sense; cinema came of age at the same time as she did. Except for dispersed traces of her existence in the archival trail–her name appears in the census, as well as other governmental documents–we have no record of her interests, favourite films, or other pastimes. She was not a magazine editor whose musings remain for posterity, but a girl who, like countless others, found pleasure in movies. If, for a brief period in 1919, Dulcie imagined herself as a movie star in the making, then she did not envision such a path for too long. Seven months later, the editors named Virginia Brown Faire, a highschooler from Brooklyn, one of the four winners of the annual edition of the contest.Footnote92 Two years later, and only eighteen at the time, Dulcie followed in the footsteps of her two older sisters and started working as a teacher.Footnote93 Drawing a sizable salary—and getting married only in her late thirtiesFootnote94—she must have had both means and time to go to the movies.

At some point during the 1930s, she moved to Wilkinson Road, which was much closer to Singapore’s commercial district than the previous address of her childhood and teenage years. While she was not destined to work in the film industry, she nourished her interest in acting. Sporadic mentions of Dulcie’s name in the press paint a picture of an eager performer, firmly embedded in her local community.Footnote95 In 1936, she was cast in the main role of a play Nine ‘Till Six performed by Singapore’s Young Women’s Christian Association’s (YWCA) ().Footnote96 The review published in The Straits Budget spoke highly of her speech, and the ‘poised, cool, competent’ woman she embodied on stage.Footnote97

Figure 5. Dulcie Foston, left, in a play staged by YWCA in Singapore. Photo published in Morning Tribune, 24 July 1936, 12.

In 1932, Dulcie and her sister Mavis visited Bournemouth; they travelled on a Balorean, a luxury liner bound for Southampton.Footnote98 This could have been the first, but certainly not the last time she set foot on British soil. At the age of forty-three, Dulcie and a small child, Tottie—presumably her daughter—emigrated to the UK, with the passenger records indicating they were heading to Glasgow from Durban, South Africa, their previous residence.Footnote99 In moving across the continents, her life exemplified the interconnectedness of the empire, and the mobility it allowed, especially to white, and white presenting people. Dulcie Marshall passed away in Taunton, in the South West of England, nearly seven thousand miles away from her birthplace. She was eighty-two years old.Footnote100

Conclusion

This article drew on multiple sources–memoirs, newspaper coverage and American trade press–to delimitate how girls living in British Malaya could have experienced cinemagoing. Interviews conducted in the 1980s, with elderly people who witnessed silent movie culture first-hand, have been particularly instrumental to this quest. What makes personal narratives so important is their ability to destabilise the concept of a standardised, national audience. To borrow from Kuhn’s astute observation, oral histories produce concrete examples of leisure habits, and the way in which they were interwoven into the fabric of ordinary lives.Footnote101

Movie fans of Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Penang, were fragmented because of their cultural heritage, as well as the overlapping lines of class division. Although class mattered a great deal, traditional mores—identifiable with one of Malaya’s key groupings—impacted the ways in which young women could relish in what the city had to offer. Perhaps Dulcie had an easier task when asserting her right to ‘territory and autonomous spaces’Footnote102 than other urbanites, such as Betty Guat Beng Seow. The problem of controlling Malayan girls was evidently not limited to cinemagoing. Being a popular pastime, however, it brought these anxieties into sharper focus. While many Muslims observers supported progressive views on gender roles, they also favoured new versions of womanhood that ‘did not totally negate the existing traditional culture.’Footnote103

Regardless of their ethnic allegiance, female moviegoers were inversely positioned at the junction of issues relating to Americanisation, commercial amusements, and the gendered dynamics of the public sphere. While some observers were apprehensive about messages carried by Hollywood, others saw the spatial organisation of film exhibition as a reason to worry. For many viewers, however, cinema was physically, and ideologically liberating: a place where they could admire and appropriate foreign fashions, but also one away from home, where they could enjoy their time with their boyfriends and girlfriends.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sharon Crozier-De Rosa for her excellent work as an editor, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. I am also grateful to Nicholas Hallows for his support and proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agata Frymus

Agata Frymus is a Senior Lecturer in Film, TV, and Screen Studies at Monash University Malaysia. She is the author of Damsels and Divas: European Stardom in Silent Hollywood (Rutgers University Press, 2020). Her work has been published in Feminist Media Studies, Celebrity Studies, and Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, amongst others.

Notes

1 Lies Van De Vijver, ‘Going to the Exclusive Show: Exhibition Strategies and Moviegoing Memories of Disney’s Animated Feature Films in Ghent (1937–1982)’, European Journal of Cultural Studies 19, no. 4 (2016): 403–18; Daniela Treveri Gennari et al., Italian Cinema Audiences: Histories and Memories of Cinema-Going in Post-War Italy (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2020).

2 Shelley Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture After the Nickelodeon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000); Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2005); Diana W. Anselmo, ‘Made in Movieland: Imitation, Agency, and Girl Movie Fandom in the 1910s’, Camera Obscura 94, no. 32 (2017): 129–63; Diana W. Anselmo, ‘Bound by Paper: Girl Fans, Movie Scrapbooks, and Hollywood Reception during World War I’, Film History 31, no. 3 (2019): 141–72.

3 Dafna Ruppin and Nadi Tofighian, ‘Moving Pictures cross Colonial Boundaries: The Multiple Nationalities of the American Biograph in Southeast Asia’, Early Popular Visual Culture 14, no. 2 (2016): 188–207, 189; Dafna Ruppin, ‘The Emergence of a Modern Audience for Cinema in Colonial Java’, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 173, no. 4 (2017): 475–502; Nadi Tofighian, ‘Mapping the Whirligig of Amusements in Colonial Southeast Asia’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 49, no. 2 (2018): 277–96.

4 Stewart, Migrating to the Movies; Diana Anselmo, Queer Way of Feeling: Girl Fans and Personal Archives of Early Hollywood (Oakland: University of California Press, 2023).

5 Amelie Hastie, Cupboards of Curiosity: Women, Recollection, and Film History (Durham and London: Duke University Press 2007), 229.

6 Kathy Fuller-Seeley, ‘Archaeologies of Fandom: Using Historical Methods to Explore Fan Cultures of the Past’, in The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, ed. Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (London: Routledge, 2018), 27.

7 Charles Joyner, ‘From Here to There and Back Again: Adventures of a Southern Historian’, in Shapers of Southern History: Autobiographical Reflections, ed. John B. Boles (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 137–63, 153.

8 Carolyn Birdsall and Elinor Carmi, ‘Feminist Avenues for Listening In: Amplifying Silenced Histories of Media and Communication’, Women’s History Review 31, no. 4 (2022): 542–60, 547.

9 To put this in perspective, a rickshaw puller would earn approximately $20 a month at the time. A blacksmith would earn anywhere between $1.35 and $2.33 for a day of work. Extrapolated from Blue Book for the Year 1924. Colony of the Straits Settlements (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1925), 2; and Jim Warren, ‘Living on the Razor's Edge: The Rickshawmen of Singapore Between Two Wars, 1919–1939’, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 16, no. 4 (1984): 38–51, 51.

10 ‘Contest Girdles the Globe. Countless Beauties Seek Fame and Fortune’, Motion Picture Magazine, May 1919, 68.

11 Number extrapolated from Lisle Foote, ‘The Fame and Fortune Contest: Week of December 20th, 1919’, Grace Kingsley’s Hollywood, December 20, 2019. https://gracekingsley.wordpress.com/2019/12/20/the-fame-and-fortune-contestweek-of-december-20th-1919/ (accessed June 16, 2024) and Misha Orgeron, ‘You Are Invited to Participate: Interactive Fandom in the Age of the Movie Magazine’, Journal of Film and Video 61, no. 3 (2009, Fall): 3−23.

12 ‘Juvenile Choir Concert’, Straits Times, April 29, 1915, 6.

13 ‘Death of Mr H.F. Foston’, Strait Times, May 17, 1904, 5; ‘Funeral Note’, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), May 18, 1904, 307.

14 ‘Marriages: Leicester-Sworder’, Pinang Gazette and the Straits Chronicle, June 12, 1925, 6.

15 ‘The Ripograph, or Giant Cinematograph’, Straits Times, May 12, 1897, 2; ‘The Ripograph’, Straits Times, May 13, 1897, 2.

16 Ruppin and Tofighian, ‘Moving Pictures Cross Colonial Boundaries’, 189.

17 K.T. Ming, ‘The First Moving Pictures Arrive in Town’, Ipoh Echo, January 16–31, 2008, 7.

18 Alexius A. Pereira, ‘The Revitalization of Eurasian Identity in Singapore’, Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 25, no. 2 (1997, Special Focus: Transformations of Ethnic Identity in Malaysia and Singapore): 7−24; 10.

19 Swee-Hock Saw, ‘Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967’, Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 1 (1969, Singapore Commemorative Issue, March): 36–49, 42.

20 J.R. Innes, Report on the Census of the Straits Settlements Taken on the 1st March 1901 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1901), 29–33. Cited in Tofighian, ‘Mapping the Whirligig of Amusements’, 280.

21 Su Lin Lewis, ‘Cosmopolitanism and the Modern Girl: A Cross-cultural Discourse in 1930s Penang’, Modern Asian Studies 43, no. 6 (2009): 1385–1419, 1388.

22 Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls; Annie Fee, ‘Les Midinettes Révolutionnaires: The Activist Cinema Girl in 1920s Montmartre’, Feminist Media Histories 3, no. 4 (2017, Fall): 162–94; Anselmo, ‘Bound by Paper’.

23 Advertising, Strait Times, November 1, 1918, 10; ‘Eastern Kinematographs Association’, Straits Times, March 13, 1917, 8; Advertising, Strait Times, November 1, 1918, 10; ‘The Way They House the Pictures in Distant Singapore’, Motion Picture News, May 15, 1920, 4204, 4212.

24 Jan Uhde and Yvonne Ng Uhde, Latent Images: Film in Singapore (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 149.

25 Suk-wai Cheong, The Sound of Memories: Recordings from the Oral History Centre, Singapore (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2019), 59.

26 ‘Picture Shows’, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, October 22, 1917, 5.

27 Daniel Chew, Oral history interview with Noel Arthur Pereira, Communities of Singapore (Part 1), May 2, 1984, accession no. 000423/13, disc 2, National Archives of Singapore.

28 Robert C. Allen, ‘Relocating American Film History. The Problem of the Empirical’, Cultural Studies 20, no. 1 (2006): 48–88; 52.

29 Beng-Huat Chua, ‘Race Relations and Public Housing Policy in Singapore’, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 8, no. 1 (1991, Winter): 343–54. See also Joel S. Kahn, Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay World (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2006).

30 Frank Swettenham, Malay Sketches (London: John Lane, 1895), 3–4. Racial stereotyping got even more problematic and elaborate in his subsequent publications. See Swettenham, The Real Malay (London: John Lane, 1899).

31 Nadine Chan, A Cinema Under the Palms: The Unruly Lives of Colonial Educational Films in British Malaya (PhD thesis, Los Angeles: University of Southern California, United States, 2015), 290.

32 Nadi Tofighian, Blurring the Colonial Binary: Turn-of-the-Century Transnational Entertainment in Southeast Asia (PhD thesis, (Stockholm: Stockholm University, Sweden, 2013), 159–60.

33 Ruppin, ‘The Emergence of a Modern Audience’, 483.

34 Ibid., 487. See also Charlotte Setijadi-Duhn and Thomas Barker ‘Imagining Indonesia: Ethnic Chinese Film Producers in Pre-independence Cinema’, Asian Cinema 21, no. 2 (2010): 25–47; M. Sarief Arief, Politik Film di Hindia Belanda (Yogyakarta: Mahatari, 2010), 20. In colonial Burma of the silent film period, the Burmese, Eurasians, Chinese, Indians, and Europeans were also watching movies under the same roof. See Chie Ikeya, Refiguring Women, Colonialism, and Modernity in Burma (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011), 104.

35 Tofighian, Blurring the Colonial Binary, 177.

36 James Burns, Cinema and Society in the British Empire, 1895–1940 (London: Palgrave 2013), 25.

37 Edwin S. Cunningham, ‘Malaysia. Moving Pictures Abroad’, The New York Clipper, June 7, 1913, 4.

38 E.I. Way, ‘The Export Market. Motion Picture Theatre Operation and Construction in Eastern Asia. British Malaya’, Exhibitors Herald-World, March 15, 1930, 69.

39 Lynn Hollen Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786−1941 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 238.

40 ‘Gaiety Cinema’, Malaya Tribune, September 2, 1926, 4.

41 Hollen Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects, 239.

42 Louise Clarke, ‘Within a Stone’s Throw: Eurasian Enclaves’, in Singapore Eurasians: Memories, Hopes and Dreams, ed. Myrna Braga-Blake and Ann Ebert-Oehlers (Singapore: World Scientific, 2017), 71–9.

43 Singapore Centenary: A Souvenir Volume (Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, 1919). Available at ‘Enter the Picture Palace’, National Library Board Singapore, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/exhibitions/sellingdreams/entertainment.php (accessed April 1, 2024).

44 ‘Foolish Wives’, Malaya Tribune, May 3, 1923, 6.

45 ‘The New Alhambra. A Preliminary View’, Malaya Tribune, January 13, 1916, 9; ‘Palladium Licence’, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, June 25, 1924, 7.

46 Yu-Lin Ooi, Oral history interview with Betty Guat Beng Seow and Koon Teck Lim, Communities of Singapore (Part 1), July 12, 1989, accession no. 000802, disc 5, National Archives of Singapore. The interviewee refers to the cinema as Pavilion, which was a name used in later decades, but not in the silent film era. This is an interesting seating arrangement if we consider that, in the US, balcony seats were considered inferior, and offer reserved for Black patrons; see David Morton and Agata Frymus, ‘A United Stand and a Concerted Effort: Black Cinema-going in Harlem and Jacksonville During the Silent Era’, in The Palgrave Handbook of Comparative New Cinema Histories, ed. Daniela Treveri Gennari, Lies Van de Vijver, and Pierluigi Ercole (London: Routledge, 2024), 27–35.

47 ‘British Malaya’, Film Daily Yearbook, 1935, 1040; Kay Tong Lim, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema (Singapore: Landmark Books for Meileen Chooy, 1991), 21.

48 Timothy Barnard, ‘Film Melayu: Nationalism, Modernity, and Film in pre-World War Two Malay Magazine’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 41, no. 1 (2010): 47–70, 49.

49 Daniel Chew, Oral history interview with Ronald Benjamin Milne, Communities of Singapore (Part 1), July 18, 1984, accession no. 000447, disc 3, National Archives of Singapore; Yu-Lin Ooi, Oral history interview with Betty Guat Beng Seow and Koon Teck Lim, 12 July, 4 September, 1989, disc 5, disc 20.

50 Marjorie Topley, Cantonese Society in Hong Kong and Singapore: Gender, Religion, Medicine and Money (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), 298.

51 Cinema Advert, Malaya Tribune, July 5, 1927, 6.

52 Yu-Lin Ooi, Oral history interview with Betty Guat Beng Seow and Koon Teck Lim, Betty Guat Beng Seow, July 10, 1989, disc 5.

53 Hollen Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects, 240.

54 Sally Alexander, ‘Becoming a Woman in London in the 1920s and 1930s’, in Metropolis London: Histories and Representations since 1800, ed. David Feldman and Gareth Stedman Jones (London: Routledge, 1989 [2016]), 264; Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship (London: Routledge, 1994), 205; Annette Kuhn, An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 73; Treveri Gennari et al., Italian Cinema Audiences, 124.

55 Kuhn, An Everyday Magic, 120.

56 Betty Lim, A Rose on My Pillow: Recollections of a Nyonya (Singapore: Armour Publishing, 1994), 17–18.

57 Ruri Ito, ‘The Modern Girl Question in the Periphery of Empire. Colonial Modernity and Mobility among Okinawan Women in the 1920s and 1930s’, in The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, ed. Alys Eve Weinbaum et al. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 240–62, 241.

58 Lois J.E. Barnett, Film and Fashion in Japan, 1923–39: Consuming The ‘West’ (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023), 25.

59 ‘Japan’s New Woman: Beauty Contests and European Dress’, Malaya Tribune, July 21, 1934, 11.

60 ‘The Eternal Question. Famous Women on the Secret of How to be Beautiful’, Straits Times, February 23, 1929, 7.

61 For African American experience of the movies, see Stewart, Migrating to the Movies; Cara Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2014). For a discussion of queer, female experience, see Anselmo, Queer Way of Feeling. Notable works on silent Hollywood and its reception in different national contexts include Laura Isabel Serna, Making Cinelandia: American Films and Mexican Film Culture before the Golden Age (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Rielle Navitski and Nicolas Poppe, eds. Cosmopolitan Film Cultures in Latin America, 1896–1960 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017).

62 Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge 2004 [1994]), 122.

63 Nadine Chan, ‘Making Ahmad Problem Conscious: Educational Film and the Rural Lecture Caravan in 1930s British Malaya’, Cinema Journal 55, no. 4 (2016): 84–107, 86.

64 Su Lin Lewis, Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920–1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 248.

65 Thienny Lee, Dress and Visual Identities of the Nyonyas in the British Straits Settlements; Mid-Nineteenth to Early-Twentieth Century (PhD Thesis, Sydney: University of Sydney, Australia, 2016), 58−62.

66 ‘Miss Nonya’, Straits Echo, October 30, 1937, 8, cited in Lewis, ‘Cosmopolitanism and the Modern Girl’, 1411.

67 See, for instance, Kathy Fuller-Seeley, At the Picture Show: Small-Town Audiences and the Creation of Movie Fan Culture (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996); Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls; Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909–1949 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001); Martin L. Johnson, Main Street Movies: The History of Local Film in the United States (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018); Richard Abel, Motor City Movie Culture, 1919–1925 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020); Agata Frymus, Damsels and Divas: European Stardom in Silent Hollywood (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 2020).

68 Sandra Khor Manickam, ‘Common Ground: Race and the Colonial Universe in British Malaya’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40, no. 3 (2009, Asian Cold War Symposium): 593–612, 594.

69 Ai Lin Chua, ‘Singapore’s Cinema-Age of the 1930s: Hollywood and the Shaping of Singapore Modernity’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13, no. 4 (2012): 592–604. See, for instance, the letter cited in the article: Molly Oh, ‘The Evils of the Modern Cinema’, The Student, August 1935, 31.

70 Ai Lin Chua, ‘Nation, Race, and Language: Discussing Transnational Identities in Colonial Singapore, circa 1930’, Modern Asian Studies 46, no. 2 (2012): 4–5.

71 Mark Emmanuel, ‘Viewspapers: The Malay Press of 1930s’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 41, no. 1 (2010, Symposium on Malay Print Culture), 3.

72 Movie Fan, ‘Criticism of Sparrows’, Straits Times, February 19, 1927, 10.

73 Chua, ‘Singapore’s Cinema-Age’, 595.

74 Joseph Benison ‘The Cinema. To the Editor Malaya Tribune’, Malaya Tribune, December 30, 1931, 3.

75 Anselmo, ‘Made in Movieland’, 137.

76 Wan Suhana binti Wan Sulong, ‘Saudara (1928–1941): Continuity and Change in the Malay Society’, Intellectual Discourse 14, no. 2 (2006): 179–202. See also Wan Suhana binti Wan Sulong, ‘Religious Issues in Malaya: A Study of Views and Debates in Saudara, 1928–41’, World Journal of Islamic History and Civilization 1, no. 3 (2011): 152–162.

77 Hashim bin Umar, ‘Modem Bagaimanakah Yang Lagi Akan Datang’, Saudara, vol. VIII, no. 624 (1936), 4, cited in Wan Suhana binti Wan Sulong, Saudara (1928–1941): Its Contribution to the Debate on Issues in Malay Society and the Development of a Malay World-View (PhD thesis, United Kingdom: University of Hull, 2003), 157−8.

78 Miss Pulau Pinang, ‘Berkehendakkan Modem Yang Sebenar’, Saudara IX, no. 663 (1936): 4, cited in binti Wan Sulong, Saudara (1928–1941), 154.

79 Cock Sing, ‘Vagrants. To the Editor of the Straits Times’, Strait Times, March 5, 1921, 10.

80 ELS, ‘To the Editor of the Strait Times’, Straits Times, March 2, 1931, 18.

81 Scott Barmé, Woman, Man, Bangkok: Love, Sex, and Popular Culture in Thailand (Maryland: Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), 73.

82 Jasmine Nadua Trice, ‘Epistemologies of the Body in Colonial Manila's Film Culture’, Feminist Media Histories 6, no. 3 (2020): 104–36.

83 Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls.

84 Ibid., 48.

85 ‘The Modern Girl. Chinese Literary Association Debate’, Malaya Tribune, December 31, 1931, 11.

86 ‘As They Do It in Hyderabad and Singapore’, Motion Picture Herald, July 2, 1932, 15.

87 ‘The Modern Girl. Chinese Literary Association Debate’, 11.

88 Yeo Geok Lee, Oral history interview with Keong Poh Chan, Communities of Singapore (Part 1), October 12, 1987, accession no. 000802, disc 4, National Archives of Singapore.

89 Lewis, ‘Cosmopolitanism and the Modern Girl’, 1403.

90 Daniel Chew, Oral history interview with Ronald Benjamin Milne, disc 3.

91 Ibid.

92 Barbara Allen, ‘A Rose in the Bud. Impressions of Virginia Brown Faire’, Motion Picture Classic, April 1920, 46–7.

93 Blue Book for the Year 1921. Colony of the Straits Settlements (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1922), 130.

94 ‘Married at Cathedral’, Straits Times, November 25, 1940, 9.

95 ‘Christmas at the Hospital’, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, December 28, 1923, 12.

96 ‘Nine till Six. Y. W. C. A Production at Victoria Theatre’, Morning Tribune, July 24, 1936, 12.

97 ‘Singapore Girls Act as London Girls’, Straits Budget, July 30, 1936, 23.

98 Balorean passenger list, 1932. Names and descriptions of British passengers, passengers no. 133 and 134, PM 23, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960.

99 Carnarvon Castle passenger list, 1946. Names and descriptions of British passengers, passengers no. 354 and 355, PM 23, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960.

100 England & Wales, Civil registration death index, 1917–2007, Dulcie Mabel M Marshall, vol. 23, 1309.

101 Kuhn, An Everyday Magic, 10.

102 Carrie Rentschler and Claudia Mitchell, ‘Introduction: The Significance of Place in Girlhood Studies’, in Girlhood and the Politics of Place, ed. Carrie Rentschler and Claudia Mitchell (New York City: Berghahn Books, 2016), 2.

103 Mahani Musa, ‘The Woman Question in Malayan Periodicals, 1920–1945’, Indonesia and the Malay World 38, no. 11 (2010): 247–71, 254.