ABSTRACT

The status of single women in the eighteenth century was precarious; homelessness and economic dependence plagued the lives of those who chose not to marry. This was the case, at least, for Mary and Charlotte Winn, the unmarried sisters of the 5th Baronet of Nostell Priory. Like many single women, the Winn sisters’ archive is sparse. But such a sparseness can be utilised and, in this instance, provides the opportunity for creative methods of recovering women’s voices. By exploring the materiality of Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters, this article demonstrates how these sisters negotiated their distance from the family home through the space they occupied on the page. Paradoxically, moreover, it is this distance that has ensured the survival of their papers. As such, the article concludes by considering the epistolary afterlives of the Winn sisters’ letters and addresses how their manuscript legacy has posthumously afforded them a place in the family’s history. In effect, paper ties to landed estates, though fragile, remain exactly that – ties.

Introduction

Girls who have been weakly educated, are often cruelly left by their parents without any provision; and, of course, are dependent on, not only the reason, but the bounty of their brothers … In this equivocal humiliating situation, a docile female may remain some time, with a tolerable degree of comfort. But, when the brother marries, a probable circumstance, from being considered as the mistress of the family, she is viewed with averted looks as an intruder, an unnecessary burden on the benevolence of the master of the house, and his new partner.Footnote1

The status of single women in the eighteenth century was precarious. A transformation in understandings of kinship and conjugality meant that, in Perry’s words, ‘the family you were born into, lost ground to the family that was created by marriage.’Footnote4 This had a particular impact on those who never married: ‘women became less important as daughters and as sisters and became more important … as mothers and wives.’Footnote5 Such precarities were heightened by the fact that sibling relationships also had the potential to threaten idealised gender roles. Amy Harris has shown how ‘[o]lder sisters’ power as elder siblings sometimes conflicted with gendered expectations of women’s passivity or docility’ and ‘sibling power [was] constantly shifting based on gender, birth order, and marital status.’Footnote6 Such a disruption, conversely, did allow certain women some freedom: in wealthier families, as Ruth Larsen has demonstrated, remaining single ‘did not mean women led secluded lives, but enabled, and encouraged, them to be active and powerful forces within the elite family and the wider world.’Footnote7 At Nostell Priory, however, the 5th Baronet’s predisposition for overspending meant that such a luxury was not an option for the Winn sisters and for them, to use Bridget Hill’s words, their time ‘in the family home lasted as long as their parents’ life.’Footnote8 Compounding this displacement is also a noticeable scarcity in writing penned by single women: Amy Froide has rightly drawn attention to the ‘lack of personal writings by most singlewomen [that] makes it difficult to assess emotional intimacy.’Footnote9 But, as this article will demonstrate, when such remaining papers are valued for their materiality as well as their content, it is possible to uncover how sibling relationships were negotiated in more subtle ways. While in many cases ‘[f]inancial and residential dependence on a brother … translated into a loss of autonomy for the sister,’ the letters of Mary and Charlotte Winn demonstrate how single women could regain a certain level of autonomy through the space they occupied on the page.Footnote10

Mary and Charlotte Winn were two of nine siblings born to the 4th Baronet of Nostell Priory and his wife Susannah Henshaw.Footnote11 Neither sister ever married and thus both remained single for the entirety of their adult lives. Both Mary and Charlotte resided at their father’s West Yorkshire home until 1765, at which point their younger brother, another Rowland, inherited the estate. This was a defining moment in the sisters’ lives; without the spousal commitment that their other siblings benefitted from, Mary and Charlotte faced both the emotional toll of leaving their family home and the economic precarity that came with relying on their brother for the payment of their annuity. This transition was especially challenging given the influential role the sisters held at Nostell Priory prior to their father’s death. Throughout their early adult lives, they managed practical and economical aspects of the estate in the 4th Baronet’s absence, from overseeing workmen to monitoring his post – perhaps made possible by the premature death of their mother.Footnote12 The sisters were trusted with more personal matters too; in 1761, the 4th Baronet asked his daughters for advice on their brother’s proposed marriage to the Swiss heiress Sabine d’Hervart, to which they replied with trepidation about being ‘greatly at a loss to keep up a conversation with her,’ and expressed concern that her presence would threaten to ‘interrupt our present Felicity, which too frequently happens when two families are united in one.’Footnote13 Incidentally, the younger Rowland ignored the concerned expressions of his father and sisters and the couple were married in 1761, a fact which perhaps accounts for the hostility between the in-laws when Rowland, now the 5th Baronet, and Sabine inherited Nostell four years later.

It is this moment that provides a particular focal point for this article; upon their brother’s inheritance of the Nostell estate in 1765, the sisters were dismissed from their home to allow room for the 5th Baronet and his new family. With this geographical distance, came emotional distance. Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters from their time after leaving Nostell complain repeatedly about unreceived replies, express regret at not being allowed to see their niece and nephew, and most commonly chase the payment of their allowances. These letters are just a small part of the mass of material in the Nostell archive: the sisters’ voices appear sporadically between 1760 and the 1790s; Rowland’s replies are largely lost aside from the odd answer copied onto the back of an original letter; and any indication of their epistolary circles beyond the Nostell family no longer remains (if one ever existed at all). The Nostell archive is also noticeably deficient in evidence pertaining to the economic particulars of the sisters’ relationship with their brother, and no records remain that detail Rowland’s payment of their annuity.Footnote14 Peculiar too is the fact that Mary and Charlotte never lived together after leaving Nostell, as was customary for families with more than one unmarried sister.Footnote15 Instead, they each resided across a number of London addresses: Charlotte at Nassau Street from 1766, Half Moon Street from 1772, and Wigmore Street from 1783, and Mary at New Norfolk Street from 1766, Bolton Street from 1768, and Great George Street from 1770. Mary appears to have spent a number of years living with their younger brother, Edmund, prior to his death in 1782, and it is evident that she also spent prolonged periods of time in Bath, presumably for the social season. In her old age, Mary settled in Exmouth, Devon. On account of these factors, the paper traces of Mary and Charlotte Winn remain in a fragmented state with little cohesion and numerous gaps, painting a patchy narrative of the sisters’ lives.

To counter these gaps, my analysis looks beyond the content of Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters. I supplement their written word with a consideration of the form, composition, and materiality of their pages. Attention to the material make up of these letters allows us to recognise epistolary lives that have not been intentionally saved and curated, but are present nonetheless. As such, this article seeks to demonstrate how the material understandings that informed sibling correspondences can be indicative of wider familial, ancestral, and household displacement. Mary’s and Charlotte’s extant papers display how the sisters negotiated their distance from the family home through the space they occupied on the page. Paradoxically, moreover, it is this distance that has ensured the survival of their voices. Consequently, I conclude this exploration with a consideration of the epistolary afterlives of these papers, addressing how textual additions to Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters have retrospectively afforded the sisters a place in their family’s history. The letters of the unmarried Winn sisters provide an example of how distance from, as opposed to proximity to, the paternal home could result in the survival of women’s manuscript traces.

Charlotte Winn (1737-1797)

Charlotte Winn was the sixth child (and sixth daughter) of nine siblings born to the 4th Baronet and Susannah Henshaw.Footnote16 Charlotte was her brother’s senior by two years and, compared with her sister Mary, appears as the more reserved of the two. Her letters remain polite and respectful despite her brother’s continued disregard. Charlotte suffered throughout her life with ill-health, which regularly impacted the contact she kept with her family. Nonetheless, thirty-eight letters penned by Charlotte are extant in the Nostell archive today; they are well-mannered and endearing but seldom elucidate how she spent her time, the circles that she moved in, or any details of her life outside of the immediate family. Charlotte’s understanding of the material composition of her writing, however, reveals insights that her letters’ content only points to in muted ways.

Charlotte’s letters are consistently neat in their form, and mostly adhere to the polite conventions of eighteenth-century letter-writing – they open with well-wishes, seldom exceed more than a page in length, and close by sending love to Rowland, Sabine, and their children. Such formulaic conventions were crucial to maintaining epistolary relationships, as Anni Sairio and Minna Nevala have commented: ‘writing in the right order [was] … a sign of politeness towards the recipient.’Footnote17 Charlotte’s hand remains uniformly tidy regardless of her ongoing ill health, and it scarcely varies across the thirty-year correspondence she maintained with her brother. Despite this fact, Charlotte repeatedly refers to her penmanship negatively. Writing to her sister-in-law on the 7th of January 1786, for example, Charlotte apologised: ‘I have little News to Entertain You with so beg you will Excuse the Stupidity of this Scraul … I am scarce able to write.’Footnote18 Likewise, addressing her brother in November 1777 Charlotte penned: ‘haveing no particular news to entertain you with, I shall not trouble you any longer with my scrawl,’ and in June 1783 she reiterated ‘I have at present no particular News to inform you with, therefore hope you’ll excuse this Stupid Scraul from a poor Invalid who does her best to subscribe herself Dr Bror.’Footnote19 Charlotte’s repeated use of the word ‘scrawl’ is conspicuous here. Reference to a writer’s ‘scrawl’ is likely to appear within any eighteenth-century correspondence; given the informality of the term, its use often denotes intimacy between writers, and such phrases can be seen as part of what Diana G. Barnes has termed ‘an epistolary vocabulary.’Footnote20 Significant in this case, however, is the fact that Charlotte’s declarations of her ‘scrawled’ hand are paired with an inability to command the pen; on the 16th of November 1782 she closed a letter to her brother by apologising ‘finding my Eye with Writeing still very weak beg you’ll excuse this sad Scraul.’Footnote21 Charlotte evidently associated her ‘scrawled’ handwriting with an incapacity to write and, as such, hints at a visual component to the term – she apologises for the appearance of her letters. Rachel Bynoth has exhibited how ‘admitting faults with the composition of letters,’ was one of the ways in which these documents ‘reinforced patriarchal hierarchies within family groups.’Footnote22 In repeatedly critiquing the appearance of her writing, therefore, Charlotte alludes to the wider power dynamics behind her epistolary relationship with her brother. Even if her letters did not appear as such, in dubbing them ‘scrawled’ missives she inadvertently reduced their worth.

Scholarship has touched upon how eighteenth-century authors might obscure their handwriting in order to disguise their correspondence – Frances Burney famously used a ‘feigned hand’ to communicate with her publisher, and Abigail Williams has shown how Johnathan Swift’s Journal to Stella was ‘made deliberately hard to read in order to create a complicity and closeness.’Footnote23 According to Stacey Sloboda, eighteenth-century copybooks proclaimed that ‘[n]eat penmanship was considered an especially useful accomplishment for young women’ and, as Deborah Heller has commented, ‘handwriting was regarded as a form of self-presentation.’Footnote24 Distinct in this case, however, is the fact that Charlotte’s writing does conform to these polite conventions, yet she refuses to give it such credit; her writing remains consistent despite assertions of her ‘scrawl’ and inability to command the pen. These comments, in consequence, suggest a correlation between her understanding of the appearance of her script and her motivation for putting pen to paper. Significantly, Charlotte’s references to her scrawl are often weighted with negative emotion; she condemns ‘the Stupidity of this Scraul,’ her ‘Stupid’ and ‘sad Scraul.’ While largely superficial, her repeated use of the term scrawl is indicative of how language associated with the appearance of letters can shed light on wider epistolary relationships, and their insecurities.Footnote25 If handwriting was a form of ‘self-presentation,’ then Charlotte’s perfect ‘scrawl’ is indicative of her uneasy and self-conscious attitude towards conversing with Rowland.

Crucially, Charlotte’s references to untidy script only appear when her letters do not relate anything of consequence. Each of her apologies are paired with regrets at not reporting any news; the ‘Stupidity’ of her ‘Scraul’ is a product of having ‘little News to Entertain … with.’ Charlotte and Rowland’s epistolary relationship, it appears, was one centred around necessity. Charlotte only deemed her writing neat if it detailed important information, regardless of the physical appearance of her hand. As Lindsay O’Neill has identified, the distribution of news within eighteenth-century letters was a key element of their purpose: ‘[c]orrespondents usually placed news at the end of a letter, as though it was an expected component, but one divorced from the letter’s initial purpose.’Footnote26 Charlotte apologises, then, because her letters stray from the norm. If, as Susan Whyman writes, ‘the epistolary balance between self-expression and controlled use of norms tipped towards more freedom’ in the eighteenth century, then Charlotte’s lack of news should not be a problem.Footnote27 That it is, though, and to such an extent as to alter her aesthetic understanding of her writing, demonstrates how Charlotte and Rowland’s correspondence was impersonal, detached, and anonymous – it reserves no room for individualism and represents the lack of intimacy between the pair.

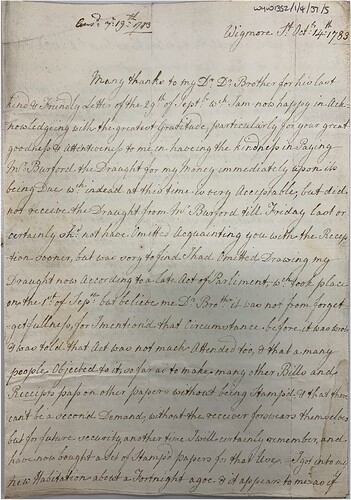

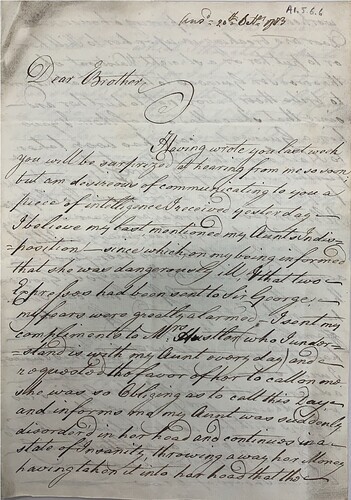

Conversely, on the occasion when Charlotte’s writing does appear to change, she makes no reference to this. During the October-November of 1783, Charlotte sent Rowland a set of four letters detailing their aunt’s poor state of health.Footnote28 Two of the letters in this collection, however, were most likely penned by a scribe – they pay little resemblance to the usual appearance of Charlotte’s hand. , for instance, is typical of Charlotte’s letters. This letter, dated the 14th of October 1783, was written just three days prior to the letter depicted in , which displays a different script entirely. Both letters are nonetheless signed ‘Ever Affectionate Sister Chartt Winn.’Footnote29 Beyond obvious changes in handwriting, there are also several stylistic changes between this scribal hand and Charlotte’s usual papers. Flourishes on the letter ‘d,’ dashes at the end of shorter lines, and the use of the older style letter ‘e,’ all support the likelihood that this second missive was written by a scribe (one with a much more traditional epistolary education than Charlotte, or someone much older).Footnote30 Contrary to her previous ‘scrawls,’ in this instance when Charlotte’s writing is clearly different, and especially so to a family member, she makes no mention of its appearance – or indeed that the letter was written by anyone else at all. What these two letters do convey, however, is important news: Charlotte discusses her dismay at her aunt’s not acquainting ‘family … first’ in regard to her illness, and writes to Rowland that ‘I dont think it right you should be kept in the Dark.’Footnote31 When read in line with her repeated apologies for untidy script at the lack of reporting anything of consequence, it seems Charlotte does not mention the appearance of her handwriting in these letters because she does not need to excuse her correspondence; this exchange is necessary and, incidentally, newsworthy. Likewise, the more traditional script and the fact that the scribe was most likely male, adds a certain level of authority to Charlotte’s writing here, one that her own hand does not ordinarily convey. These factors, alongside Charlotte’s references to the appearance of her script in letters that present no difference in neatness but do consist of more trivial content, display how she employed aesthetic understandings to the composition of her letters as a sort of epistolary censorship – a means of traversing the unpredictability of her brother’s communication. As such, while Charlotte’s voice remains sporadic in the Nostell archive and with little in the way of a comprehensive record, an exploration of the form of these papers can illuminate a more complex narrative surrounding the Winn siblings’ relationship and the extent of Charlotte’s distance from the family. The sensitivity Charlotte paid to her script communicates her awareness of the precarious status she held.

Mary Winn (1736-1800)

Mary Winn was one year Charlotte’s senior, and three years older than her brother, Rowland.Footnote32 In stark contrast to Charlotte’s polite demeanour, it was Mary who caused the most strain. Much more headstrong and independent than her sister, Mary never had any qualms about reproaching her brother for his ineptitudes; her feisty personality appears to have cost her a relationship with many of her siblings and she went a number of years without speaking to Charlotte despite the solidarity offered by their shared situation. Unsurprisingly, Mary’s papers display a much more explicit use of her letters’ materiality as a means of negotiating a relationship with her brother.

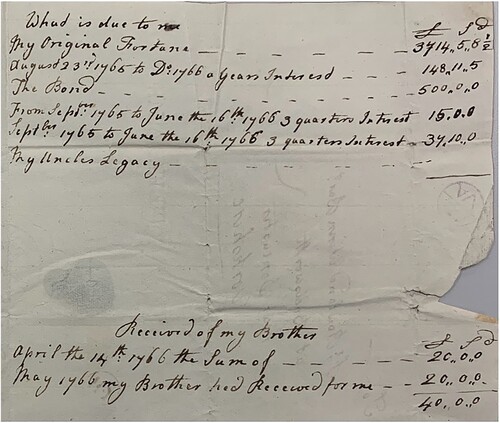

Whereas Charlotte’s papers consistently adhere to letter-writing conventions, Mary’s pages are often dramatically altered in order to accentuate her reasons for writing. In instances where she reproaches Rowland for the ever-late payment of her annuity, for example, Mary purposefully adjusts the form of her letters to ensure her requests are not overlooked. In one instance, dated the 30th of August 1766, merely a year after the death of their father and Rowland’s inheritance of the estate, Mary alters the entire second page of her letter to provide a detailed breakdown of the money she is owed (see ). ‘According to your desire’ she writes, ‘I have sent on the other side of this Letter an exact account [of] how our affairs stand between us.’Footnote33 That this missive was specifically requested by Rowland instantly indicates a level of distrust between the pair. But more than this, in providing a breakdown of costs Mary uses the form and layout of her letter to interrupt and displace the social and informal nature of how siblings were expected to correspond. Letters were fundamental to maintaining familial ties and, as Amy Harris has noted, ‘[l]ove or fondness was meaningless without … affectionate expressions in deed and in spoken and written word.’Footnote34 Far from a relaxed conversation between brother and sister, Mary’s epistolary accounts display formality, organisation, and an awareness of her brother’s (poor) financial management. As James Daybell asserts, such manipulations ‘are fundamental to the material rhetorics of the manuscript page.’Footnote35 Just as Charlotte’s adherence to polite conventions is symptomatic of her and Rowland’s lack of intimacy, Mary’s fiscal missives allude to a business-like exchange in the place of sibling affection.

Figure 3. Letter from Mary Winn to Rowland Winn providing a breakdown of the money she is owed, 30th August c. 1766. West Yorkshire Archive Service WYW1352/1/4/2/60.

Mary’s method of corresponding did not go unnoticed; on the 23rd of January 1773, following a lengthy account of the difficulty she faced in receiving her annuity, Mary wrote:

… in your last Letter I received from you, you told me you never hear from me, but when you want Money, I do confess it it is very true, but the reason of my not troubling you with any of my Scrawls was because I use to write both to yourself & my Sister and they were never answer’d so thought they were not acceptable.Footnote36

Ever the more headstrong and confrontational of the pair, Mary also made more explicit use of the materiality of her letters to bolster or reinforce their contents. Rowland’s ongoing hostility had lasting consequences on the Winn sisters, and they remained unwelcome at Nostell even once their nephew (another Rowland) inherited the estate in 1785. During the latter years of her life, Mary rekindled a relationship with her niece, Esther Sabina, who had incidentally also been banished from Nostell on account of her elopement with the family baker.Footnote37 This renewed friendship materialises in the form of a small cache of seventeen letters, spanning the years 1797-1799. These letters are penned by Mary and addressed to her niece, and plot the pair’s disputes with the 6th Baronet and his widowed mother. This correspondence not only displays how Mary’s resentment endured long after her brother’s death, but it also reveals how ‘the Malice … of the family,’ to use Mary’s phrase, was experienced by generations to follow.Footnote38

Particularly evident in this set of letters is Mary’s manipulation of the material qualities of her paper. Writing on the death of her sister-in-law Sabine in 1798, Mary acknowledged her choice to disregard using black wax to seal her letter:

You will be surprised to see I have Not Cealed this Letter with Black Wax, but Sir Rowland has not thought [it] proper to acknowledge any of us as his Relations by not ordering his Steward to write to acquaint us of his Mother’s death, which is always done to the most distant Relation when such an Event takes place in a family.Footnote39

An exploration of the broader paratexts of this set of letters is equally as revealing about Mary’s lasting displacement from her family. Her use of postscripts, for example, reveals the extent to which her banishment from Nostell impacted her ability to settle for years to follow. Postscripts hold an ambiguous place in the body of the letter; appearing after the signature they are inherently distinct from the missive itself, on par instead with ‘the dating formula’ that begins the document.Footnote44 But as Fay Bound notes, these appendages could also be seen as intimate salutations giving ‘an impression of unwillingness to part with a lover, or of emotional expression being unable to be contained by the parameters of the text.’Footnote45 Susan Whyman has also noted how such additions can indicate the writer belonging to a certain social or religious group; Quaker postscripts for example largely display ‘spiritual love instead of [the more common] ‘humble services’.’Footnote46 The postscript, therefore, while detached from the letter and often sparse in its content, has the potential to illuminate hidden details about its author.

Mary’s postscripts in the cache of letters addressed to her niece expose how she endured a permanent state of homelessness after her departure from Nostell. These additions play a purely functional role; they include directions and instructions for where (and to who) Esther Sabina should send her replies. Across the total of seventeen letters, Mary added a postscript detailing her location to fourteen, and out of these fourteen postscripts, covering just two years, she provides six different addresses. These can be particularly lengthy additions such as the postscript added to the letter from the 19th of September 1798 in which Mary writes ‘Direct your Letter for me at Mrs Fetherstones on the Cliff Scarbrough Yorkshire,’ or to the one dated the 30th of August the same year: ‘If you answer this in the Course of a Fortnight, your Letter will find me at Sr George Stricklands Bart at Boynton, near Malton, Yorkshire.’Footnote47 Where more brief postscripts exist such as that added to a letter dated May the 23rd c.1797 which simply notes ‘Maddox Street,’ they are paired with supplementary instructions for postage in the body of the letter itself: ‘do give me a line under Cover to Sir George Allenson Winn Road Lower Brook Street London.’Footnote48 Across this set of letters, Mary’s repeated use of her postscript to provide address instructions alludes to a nomadic lifestyle and lack of a fixed and permanent home. This is especially poignant given the fact that Mary had, by this point in her life, been banished from Nostell longer than she had lived there. Many scholars have written on the importance of having a fixed address to constructions of identity; beyond providing a ‘myriad [of] social privileges’ it was also the site of self-expression.Footnote49 Eighteenth-century fiction, as Beth Cortese has demonstrated, ‘showed how daughters … had to create their own comfortable marital home following the loss of their family home and its connection to their identity.’Footnote50 In never marrying, Mary was not afforded such a luxury – her identity remained tied to Nostell Priory. Consequently, Mary’s use of her postscripts to provide frequent updates regarding her address symbolises not only her displacement from the Nostell family and its epistolary network, but also alludes to the restraints this placed on her sense of identity.

Richard Terry has demonstrated how postscripts were ‘inevitably bound up with an author’s self-consciousness about concluding or failing to conclude.’Footnote51 In this respect, it is possible to read Mary’s additions as symptomatic of her broader melancholy at not having a permanent home. As she lamented on June the 23rd c.1799, less than a year before her death:

I went to Bath in the Spring, and passed five Weeks there, and was only Just returned to this place when I received your Letter, since that time I have been in a very unsettled state, wishing very much to settle in Yorkshire, and nothing can I hear of, that is likely to suit me so am obliged to continue in a ready furnished House in Exmouth, without many comforts about me, which I have been accustom’d to, there is nothing like a place of ones own, and there is a pleasure in having every thing neat.Footnote52

Epistolary afterlives

Thus far, I have demonstrated how the form and material understandings of the Winn sisters’ letters yield numerous insights into the strains and tensions of their relationship with their brother. These readings go some way towards revealing how both Mary and Charlotte relied on the exchange of paper to maintain and negotiate their emotional, social, and financial proximity to their parental home. But in spite of their ongoing and lasting exclusion from the family, the fact remains that the sisters’ papers are extant within the Nostell archive today; Mary and Charlotte are very much a part of the manuscript legacy of their family, even if their lived experience was far from this. With this in mind, my analysis now turns to the afterlives of these texts, exploring the journey such pages took after they were posted. Here, I address the superscriptions and additions outside of the body of the letter: hallmarks such as postal stamps, added labels, and catalogue markings all expose the afterlives of these papers. Through these additions, it is possible to piece together the wider contours of Mary’s and Charlotte’s status in the family – their letters received the home at Nostell that the sisters were long denied.

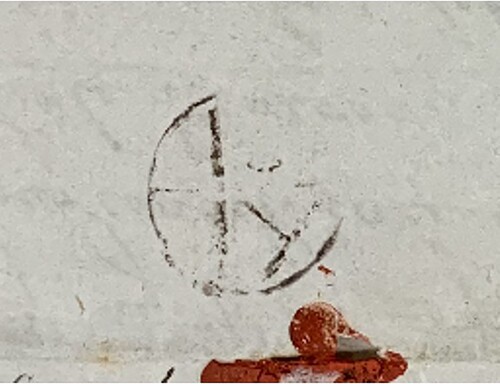

As has been established, Rowland’s epistolary relationship with his sisters was irregular and often far from cordial: the state in which Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters remain in the Nostell archive only serves to reinforce this. Across approximately a third of the sisters’ letters is an annotation in Rowland’s hand, appearing at either the top of the page or on the envelope. These are mostly brief and take the form of reminders, such as ‘Miss M- Winns Letter from London Augst 30th 1766’ or ‘Answer’d this Letter ye 20th Octbr 1770.’Footnote54 The most common of these labels is Rowland’s note as to whether he replied to his sisters or not. This inscription, though brief, holds numerous insights. More consistent with his dates, Rowland often provides information otherwise unknown. Likewise, in cases when Mary and Charlotte do recall the date of their writing, Rowland’s inscription, alongside the postmark, reveal the length of time it took for their letters to arrive and be replied to. Markman Ellis has made use of such ‘metadata’ to analyse Elizabeth Montagu’s letter collection, shedding light on how these marks can plot a letter’s journey.Footnote55 In a similar vein, such additions on the Winn sisters’ letters provide a real-time perspective to their correspondence. Rowland’s longest absence, for example, occurred in 1783. Charlotte wrote to her brother on ‘July 15th’ but Rowland’s memorandum indicates that he did not answer the letter for almost six weeks: ‘Ansd [on the] 25th Augst 1783.’Footnote56 While the postmark is not clear (see ), it does demonstrate that this letter was in transit on the 15th, 16th, or 18th of July, meaning Rowland waited almost forty days before answering his sister. These material indicators, moreover, are substantiated by the sisters’ pleas about Rowland’s lack of reply. On the 23rd of March 1782, for example, Charlotte lamented her brother’s lack of reply to at least four of her previous letters: ‘I hope you rec:d within these last 6 Months the 4 Letters I have wrote to you … none of which you have been so kind in favouring me with an Answer.’Footnote57 Once such supplementary markers, therefore, are contextualised with the sisters’ appeals for a regular correspondence, Rowland’s labelling serves to exhibit his less than reliable epistolary practices and his emotional distance from his siblings – replying to their letters was evidently not a priority.

Figure 4. Postmark on a letter from Charlotte Winn, 15th July 1783. West Yorkshire Archive Service, WYW1352/1/4/37/3.

The sisters’ constant pleas regarding unreceived letters are bolstered by the postmark evidence these papers bear; Rowland alienated his sisters from the emotional and epistolary hub of their family home. But while Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters illustrate their permanent removal from the Nostell estate, the fact these papers remain part of the archive today is testament to the longevity of such documents – indeed, that the letters are labelled at all attests to some interaction with these pages beyond the point they were received. Nostell Priory’s archive is vast and in 1776 Rowland commissioned Robert Adam to create a ‘room for keeping the family writings’; the product of this commission is the muniments room, which is extant in the house today (albeit empty).Footnote58 Such alterations, alongside the fact Mary and Charlotte were also accustomed to receiving letters written by their brother’s steward (who it is likely would have worked in the muniments room), suggests the sisters’ letters were stored in this space. Dena Goodman has demonstrated how changes in the use of eighteenth-century furniture sought to distance men’s and women’s writing, not to merge them. Gentlemen enjoyed larger writing spaces ‘when engaged not in the leisure of writing familiar letters but in the work of the pen,’ in contrast to women’s ‘small writing desk[s].’Footnote59 At Nostell though, it seems that women’s papers could be found within and amongst the much more masculine estate papers that made up the rest of the muniments room: extant labels on the bookcases include ‘steward annual accounts and papers relative to the same.’ Pigeonhole labels such as ‘Lettres et Papiers d’Affairs dans la Suisse’ also suggest that the papers of Sabine (Rowland’s Swiss wife) were similarly preserved in this room.Footnote60 Nostell’s muniments room was used for storing the family papers up until their removal to the county archives in the 1980s, a fact which perhaps accounts for the survival of the eighteenth-century labels. And, while the discovery of papers in much more unconventional locations (under floorboards and within library crevices) suggests that archival preservation was not the family’s utmost priority, the residual paint traces of the pink, white, and green Robert Adam decorative scheme alongside gilt lettering on the inside of the extant bookcases indicate that this room was significantly esteemed in the eighteenth century. That Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters may have appeared together with those relating directly to estate management, in a location that was evidently of important value, demonstrates how women’s papers could coexist alongside those of a more formal and masculine nature, within the prized walls of the house itself. Susan Whyman, in the context of the Verneys at Clayton House, has revealed how letters, when retained for prolonged periods of time in the family home, continued ‘functioning as a legacy, shaping, not just reflecting, a family ethos,’ ‘[l]ong after their genesis.’Footnote61 The longevity of the sisters’ letters at the site from which they were long excluded from, therefore, affords them a retrospective legacy within the family through the paper mementos they left behind. As James Daybell has noted, such letters ‘were “monumentalized,” considered worthy of preservation, and assumed a particular status within the household.’Footnote62 In this context, Mary’s and Charlotte’s paper traces exist not only within the masculine realm of estate management, but also within the patrilineal ancestry of the family name. Paradoxically then, it is through their brother’s impersonal archiving that the sisters have gained a place in their family’s history, despite their ongoing emotional and familial displacement.

More than this, the fact that the sisters’ papers remain within the Nostell collection today despite the displacement they experienced during their lifetime is testament to the importance of these fragile traces. As Leonie Hannan asserts, letters ‘linked women to … ‘spaces’ or networks of exchange,’ even those from which they were excluded.Footnote63 The epistles discussed in this article are not only the legacy of the Winn sisters’ exclusion from their family home, but they are also the very sites of their involvement with it. These pages provided Mary and Charlotte with a space to negotiate their proximity to the country house while also exposing the wider privileges and precarities surrounding the survival of such documents. Indeed, these patchy narratives embody the ambiguous and often-strained nature of single women’s experiences of the country house. When valued for their material as well as textual insights, such narratives are not necessarily as sparse as they may first appear, and fragmented archives such as those of Mary and Charlotte Winn, can be equally as revealing as comprehensive records. While Wollstonecraft may have been correct in her statement that unmarried sisters were ‘an unnecessary burden on the benevolence of the master of the house,’ Mary’s and Charlotte’s letters remain embedded with and alongside those of the rest of their family – in today’s setting they are difficult to view with ‘averted looks.’ As such, paper ties to landed estates, though fragile, remain exactly that – ties. The materiality and form of these letters demonstrate that, for Mary and Charlotte Winn, the space they occupied on the page was fundamental to maintaining a connection to their ancestral home.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katie Crowther

Katie Crowther is a research assistant on the digital project the Elizabeth Montagu Correspondence Online and a research associate at the University of York's Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies. She recently completed her PhD, Women’s Paper Traces: Material Manuscripts, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Country House, at the University of York in collaboration with the National Trust.

Notes

1 Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men: with A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and Hints, ed. Sylvana Tomaselli (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 141. This passage was originally quoted in Bridget Hill, Women, Work, and Sexual Politics in Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1989), 228.

2 Ruth Perry, Novel Relations: The transformation of Kinship in English Literature and Culture, 1748-1818 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 42.

3 Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility, ed. John Mullan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 6. For scholarship on brother/sister relationships in eighteenth-century fiction see: Deborah J. Knuth Klenck, ‘“You Must be a Great Comfort to Your Sister, Sir”: Why Good Brothers Make Good Husbands,’ Persuasions On-line 30, no. 1 (2009), https://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol30no1/klenck.html? (accessed October 6, 2022); Ellen Pollak, Incest and the English Novel, 1684-1814 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003); Julie Shaffer, ‘Familial Love, Incest, and Family Desire in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century British Women’s Novels,’ Criticism 41, no. 1 (1999): 67-99; Naomi Tadmor, ‘Dimensions of inequality among siblings in eighteenth-century English novels: the cases of Clarissa and The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless,’ Continuity and Change 7, no. 3 (1992): 303-33; Susan Allen Ford, ‘‘Exactly what a brother should be’? The failures of brotherly love,’ Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal (Print Version) 31 (2009): 102.

4 Ruth Perry, ‘Brotherly Love in Eighteenth-Century Literature,’ Persuasions On-line 30, no. 1 (2009), https://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol30no1/perry.html? (accessed October 6, 2022).

5 Ibid; see also, Perry, Novel Relations, 34.

6 Amy Harris, ed., Family Life in England and America, 1690-1820 vol. 3 (London: Routledge, 2016), 168; Amy Harris, ‘That Fierce Edge: Sibling Conflict and Politics in Georgian England,’ Journal of Family History 37, no. 2 (2012): 157.

7 Ruth Larsen, ‘For Want of a Good Fortune: elite single women’s experiences in Yorkshire, 1730-1860,’ Women’s History Review 16, no. 3 (2007): 397.

8 Bridget Hill, Women Alone: Spinsters in England, 1660-1850 (London: Yale University Press, c. 2001), 70.

9 Amy M. Froide, Never Married: Singlewomen in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 54.

10 Ibid., 62.

11 For a biographical record of the Winn siblings see: Kerry Bristol, ‘Families are ‘sometimes … the best at a distance’: sisters and sisters-in-law at Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire,’ in Women and the Country House in Ireland and Britain, ed. Terence Dooley, Maeve O’Riordan and Christopher Ridgeway (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2018), 33-56.

12 See for example Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 4th Baronet, 23 May 1765, Nostell Priory (Winn Family), Baron St Oswald, Family and Estate Records, WYW1352/1/1/4/18, Wakefield, West Yorkshire Archive Service. All subsequent archival references to the Winns are from this collection.

13 Susannah Winn, Ann Winn, Mary Winn, Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 4th Baronet, 28 November 1761, WYW1352/1/1/4/15.

14 I am particularly grateful to the expertise of Kerry Bristol for this knowledge, and her impeccable familiarity with the Nostell archive.

15 Froide, Never Married, 55-56.

16 The Winn family tree can be found in: Bristol, ‘Families are ‘sometimes … the best at a distance,’ 35.

17 Anni Sairio and Minna Nevala, ‘Social Dimensions of Layout in Eighteenth-Century Letters and Letter-Writing Manuals,’ Studies in Variation and Change in English 14, (2013), https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/14/sairio_nevala/ (accessed October 4, 2002).

18 Charlotte Winn to Sabine Winn, 7 January 1786, WYW1352/1/4/11/1.

19 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 16 November 1777, WYW1352/1/1/5/6/4; Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 23 June 1783, WYW1352/1/4/37/4.

20 Diana G. Barnes, ‘Emotional Debris in Early Modern Letters,’ in Feeling Things: Objects and Emotions Through History, ed. Stephanie Downes, Sally Holloway, and Sarah Randles (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 115.

21 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 16 November 1782, WYW1352/1/4/3/13.

22 Rachel Bynoth, ‘A Mother Educating her Daughter Remotely through Familia Correspondence: The Letter as a Form of Female Distance Education in the Eighteenth Century,’ History 106, no. 373 (2021): 739.

23 George Justice, ‘Burney and the Literary Marketplace,’ in The Cambridge Companion to Frances Burney, ed. Peter Sabor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 149-50; Abigail Williams, ‘‘I Hope to Write as Bad as Ever’: Swift’s Journal to Stella and the Intimacy of Correspondence,’ Eighteenth Century Life 35, no. 1 (2011): 112.

24 Stacey Sloboda, ‘Between the Mind and the Hand: Gender, Art and Skill in Eighteenth-Century Copybooks,’ Women’s Writing 21, no. 3 (2014): 341; Deborah Heller, ‘Elizabeth Vesey’s Alien Pen: Autobiography and Handwriting,’ Women’s Writing 21, no. 3 (2014): 364.

25 In a similar vein Amanda Vickery’s study of the vocabulary surrounding descriptions of wallpaper, concludes that individuals ‘were adept in applying their everyday language of aesthetic discrimination in very precise ways to … particular visual characteristics.’ Amanda Vickery, ‘‘Neat and Not To Showey’: Words and Wallpaper in Regency England,’ in Gender, Taste, and Material Culture in Britain and North America, 1700-1830, ed. John Styles and Amanda Vickery (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2007), 219.

26 Lindsay O’Neill, The Opened Letter: Networking in the Early Modern British World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 171.

27 Susan Whyman, The Pen and the People: English Letter Writers 1660-1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 21.

28 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 17 October 1783, WYW1352/1/1/5/6/6; Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 2 November 1783, WYW1352/1/1/5/6/7; Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 4 November 1783, WYW1352/1/4/1/48; Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 10 November 1783, WYW1352/1/4/1/47.

29 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 17 October 1783, WYW1352/1/1/5/6/6.

30 WYW1352/1/4/1/48 contains a letter written by James Coxeter in the same hand, suggesting he could be acting as Charlotte’s scribe. Coxeter is also mentioned in Charlotte’s will indicating a close relationship between the two and worked for the Bank of England, which would attest to his more traditional style of handwriting. See: Will of Charlotte Winn, Spinster of Saint Marylebone, Middlesex, 28 April 1797, The National Archives, Kew. PROB 11/1290/22; Merchants, etc. Declaration of the Merchants, Bankers, Traders, and Other Inhabitants of London, made at Grocers’ Hall, December 2nd, 1795 … (London: Philanthropic Reform, 1795), 35.

31 Charlotte to Rowland, 14 October 1783, WYW1352/1/4/37/5.

32 Bristol, ‘Families are ‘sometimes … the best at a distance,’ 44.

33 Mary Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 30 August c. 1766, WYW1352/1/4/2/60.

34 Amy Harris, Siblinghood and Social Relations in Georgian England: Share and Share Alike (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 67.

35 James Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practice of Letter-Writing, 1512-1635 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 2.

36 Mary Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 23 January 1773, WYW1352/1/4/3/30.

37 Bristol, ‘Families are ‘sometimes … the best at a distance,’ 63.

38 Mary Winn to Esther Sabina Williamson, 3 December c. 1797, WYW1352/1/4/36/6.

39 Mary Winn to Esther Sabina Williamson, c. 1798, WYW1352/1/4/36/4.

40 Sue Walker, ‘The Manners of the Page: Prescription and Practice in the Visual Organization of Correspondence,’ The Huntington Library Quarterly 66, no. 3-4 (2003): 327. See also Joe Nickell, Pen, Ink, & Evidence: A Study of Writing and Writing Materials for the Penman, Collector, and Document Detective (New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press, 2000), 89-91.

41 See for example Mary Winn to Esther Sabine Williamson, 3 May 1797, WYW1352/1/4/36/14; Mary Winn to Esther Sabine Williamson, 15 September c. 1797, WYW1352/1/4/38/19.

42 Mary Winn to Esther Sabina Williamson, c. 1798, WYW1352/1/4/36/4.

43 My understanding of this phrase stems from the work of Serena Dyer and Chloe Wigston Smith see: Serena Dyer, ‘Barbara Johnson’s Album: Material Literacy and Consumer Practice, 1746-1823,’ Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 42, no. 3 (2019): 263-282; Serena Dyer and Chloe Wigston Smith, ‘Introduction,’ in Material Literacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Nation of Makers, ed. Serena Dyer and Chloe Wigston Smith (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 1-16; Daybell also alludes to a similar understanding writing of ‘the range of literacies (written, visual and oral) associated with letter-writing,’ Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England, 16.

44 Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England, 12.

45 Fay Bound, ‘Writing the Self? Love and the Letter in England, c. 1660-c. 1760,’ Literature and History 11, no. 1 (2002): 9.

46 Whyman, The Pen and the People, 151.

47 Mary Winn to Esther Sabina Williamson, 19 September 1798, WYW1352/1/4/36/3; Mary Winn to Esther Sabina Williamson, 30 August c. 1798, WYW1352/1/4/36/7.

48 Mary Winn to Esther Sabine Williamson, 23 May c. 1797, WYW1352/1/4/36/2.

49 Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 6.

50 Beth Cortese, ‘Home Economics: Female Estate Managers in Long Eighteenth-Century Fiction and Society,’ in At Home in the Eighteenth Century: Interrogating Domestic Space, ed. Stephen G. Hague and Karen Lipsedge (Milton: Taylor and Francis, 2021), 140.

51 Richard Terry, ‘‘P.S.’: The Dangerous Logic of the Postscript in Eighteenth-Century Literature,’ The Modern Language Review 109, no. 1 (2014): 41.

52 Mary Winn to Sabina Williamson, 23 June 1799, WYW1352/1/4/36/17.

53 Will of Mary Winn, Spinster of Littleham, Devon, 10 June 1800, The National Archives, Kew. PROB 11/1344/53.

54 Mary Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 30 August 1766, WYW1352/1/4/2/60; Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 10 October 1770, WYW1352/1/4/2/27.

55 Markman Ellis, ‘Letters, Organization, and the Archive in Elizabeth Montagu’s Correspondence,’ Huntington Library Quarterly 81, no. 4 (2018): 624.

56 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 15 July 1783, WYW1352/1/4/37/3.

57 Charlotte Winn to Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet, 23 March 1782, WYW1352/1/1/5/6/5.

58 Memorandum for Mr Adam, listing work to be completed at Nostell Priory, August 1776, WYW1352/3/3/1/5/2/20. See also: ‘The Nostell Priory Muniment Bookcases – circa 1776,’ NT 959803, National Trust Collections, National Trust and Robert Thrift, accessed October 4, 2022, http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/959803; ‘The Nostell Priory Muniment Bookcases – circa 1776,’ NT 959804, National Trust Collections, National Trust and Robert Thrift, accessed October 4, 2022, http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/959804.

59 Dena Goodman, Becoming a Woman in the Age of Letters (London: Cornell University Press, 2009), 229.

60 Megan Wheeler, ‘The Nostell Priory Muniment Bookcases – circa 1776,’ National Trust Collections, last updated 2017, accessed October 7, 2022, https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/959803.

61 Susan Whyman, ‘‘Paper Visits’: The Post-Restoration Letter as Seen through the Verney Family Archive,’ in Epistolary Selves: Letters and Letter-Writers, 1699-1945, ed. Rebecca Earle (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), 25.

62 James Daybell, ‘Gendered Archival Practices,’ in Cultures of Correspondence in Early Modern Britain, ed. James Daybell and Andrew Gordon (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2016), 214.

63 Leonie Hannan, ‘Making Space: English Women, Letter-Writing, and the Life of the Mind, c, 1650-1750,’ Women’s History Review 21, no. 4 (2012): 601.