ABSTRACT

This article explores some of the ways in which queer women living in country houses have used their economic privilege and class leverage for their own purposes, disrupting and reshaping country house living to make space for their own independent endeavours. It takes as its case study the life of Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie (1895–1985), an innovative woman potter in the early British studio ceramics movement who rejected aristocratic, familial and societal expectations of duty and lineage to self-fashion an identity as an artist. Pleydell-Bouverie created a separate household on her family estate of Coleshill where she prioritised pleasurable domesticity with her female partners alongside creative expression and productivity. This essay investigates Pleydell-Bouverie’s use of the estate – both the conditions it afforded her and its ecological materiality – as a resource in her experimental artistic practice and in her alternative, non-heteronormative mode of living.

Introduction

In their introduction to the edited volume, Women and the Country House in Ireland and Britain (2018), the editors noted that although the figure of the ‘landed wife’ appeared frequently in the collected essays, unmarried women were ‘a rarer sight … reflecting their greater invisibility among the family papers of the wealthy elite’.Footnote1 But what of those women who were not only unmarried but actively sought a same-sex partner? Given the dynastic and familial expectations foundational to the notion and survival of the aristocratic country house, how have non-heteronormative or queer women built a life within this context? This essay presents a single case study, that of Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie (1895–1985), who used the economic privilege and agency afforded to her through her aristocratic background to reconfigure country house living and establish a separate household on her family estate of Coleshill, north-east of Swindon.

In removing herself from the historically coded and gendered spaces of the main house to an outlying cottage on the estate (Mill Cottage), Pleydell-Bouverie constructed an environment that enabled creative productivity and allowed her to live as she wished with her female partners. Surveying papers and correspondence that survived due to Pleydell-Bouverie’s artistic connections (rather than being retained by a family archive), this article will consider the ways in which Pleydell-Bouverie challenged contemporary expectations in relation to class, gender, sexuality and their intersections. It will interrogate her conversion of a space used historically by working people, her undertaking of physical labour and her appearance, and her mastery of wheel-thrown studio pottery, a discipline previously associated solely with men of a lower, artisanal class. It will question to what extent Pleydell-Bouverie’s choices and experiments were evidence of her exploration of gender identity, and to what extent they signified a search for modernity – a new way of living – in which she could escape and even defy the bonds of family and aristocracy and instead fashion an identity as an artist. As well as observing the practical benefits of Mill Cottage to Pleydell-Bouverie and her female partners, notably the privacy it gave them, this article will draw on archival correspondence to explore the significance of the ‘rural idyll’ to their queer way of life and the centring of private pleasure and creativity over familial duty and responsibility. Furthermore, I argue that Pleydell-Bouverie’s queering of the estate reached beyond her mode of living and encompassed her rejection of the heteronormativity long associated with inheritance and country house living, such as improving the appearance of the land. Instead, she used the estate as a material resource in her own artistic practice, which prioritised process and experimentation. Finally, I consider my 2019 visit to the extant physical fabric of Coleshill and question the obscuring of this queer aspect of the country house and estate in the curatorial interpretation presented to visitors.

Purchased by collectors and museums since the 1920s, the ceramics made at Coleshill by Pleydell-Bouverie, and those made there by her partner, potter Norah Braden (1901–2001), feature in more than thirty museum collections across Britain and North America [ and ]. Although these handmade ceramics have been recognised, praised and collected, there has been little serious contextual and critical engagement with the wider artistic practice of this pair, or their position as women artists. Most frequently, the two women have been written about solely in relation to other contemporary (male) British potters, their biographies (Braden’s often full of inaccuracies) inserted into wider narratives about British studio pottery as a movement.Footnote2 Like many long-practising women artists, towards the end of her life Pleydell-Bouverie eventually received recognition in the form of one small retrospective exhibition accompanied by a pamphlet and, five years later, a short monograph, which provides vital factual information but little in the way of critical or contextual analysis.Footnote3 Pleydell-Bouverie herself published occasional articles on her glaze recipes but most primary source material relating to these women takes the form of notebooks given by them to the Crafts Study Centre (CSC), Farnham (part of the University for the Creative Arts).Footnote4 The CSC also holds the archives of other craftspeople, including Bernard Leach, whose archive contains dozens of letters sent to him by Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden. My recent discovery of Braden’s personal papers (now donated to the CSC) provides further evidence of their life together at Coleshill and forms the bedrock of my ongoing doctoral research. This article therefore represents a first attempt to situate the domestic life created by Pleydell-Bouverie on her family estate in the wider context of other queer interwar relationships in a rural setting, questioning the extent to which her life and work subverted the role expected of her as a member of the aristocracy and the granddaughter of an Earl.

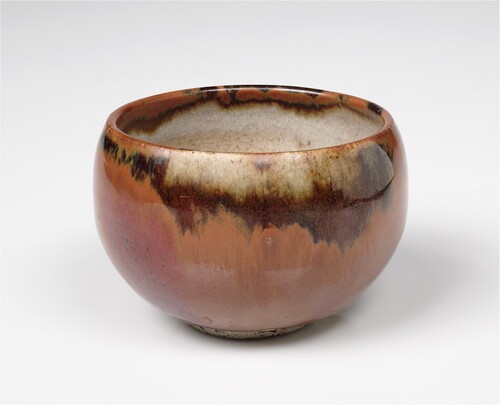

Figure 1. Bowl, stoneware with grass ash glaze and brushed iron decoration, made by Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie at Coleshill, c. 1928–36. From the collections of the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, P.74.135.

Figure 2. Vase, stoneware with box ash glaze and brushed iron decoration, made by Norah Braden at Coleshill, c. 1928–36. From the collections of the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, P.74.173.

Coleshill House was the second home of the Pleydell-Bouverie family after their principal residence, Longford Castle, Wiltshire. Built by Sir Roger Pratt (1620–84) between 1650 and 1660, for his cousin Sir George Pratt, Coleshill was thought to have been at least partly designed by Inigo Jones and was described by Pevsner as ‘the best Jonesian mid-seventeenth century house in England’.Footnote5 Known for its double flight staircase and carved ceilings, Coleshill was admired into the twentieth century: an extensive article, with accompanying photographs, appeared in Country Life in 1904.Footnote6 The estate included the village of Coleshill as well as surrounding farms and woodland. Coleshill House was inherited by Katharine’s father Duncombe Pleydell-Bouverie (1842–1909), the second son of the 4th Earl of Radnor. He and his wife Maria Elenor Hulse (d. 1936) had three children – a son, Jacob (1887–1914), and two daughters, Mary (1885–1965) known as Molly, and Katharine (1895–1985). After Duncombe’s death in 1909 and his son’s subsequent death during the first months of the First World War, Coleshill was inhabited only by Maria and her two daughters, neither of whom would marry or have children.

After ‘canteening’ in French hospitals during the First World War, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie turned to ceramics. Seeing Roger Fry’s handmade ceramics produced for the Omega Workshops inspired her to attend one of the few pottery courses available at that time, at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London. After a chance meeting with pioneering studio potter Bernard Leach (1887–1979) in 1923, she joined his new pottery in St Ives, Cornwall, for a year. A paying student, Pleydell-Bouverie helped out with odd jobs and observed Leach and Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke (1894–1932), a visiting Japanese potter who re-built Leach’s three-chambered climbing kiln, the first of its kind in Europe. She was joined in St Ives by her partner, the artist Ada Mason, known as ‘Peter’ (1897–1942), whom she had met at the Central School and lived with in London. After a year at the Leach Pottery, Pleydell-Bouverie decided to return to Coleshill with Mason and build a pottery of her own, converting a cottage attached to a water mill. With unlimited and free access to material available on the estate, the pottery was perfectly situated. Power was provided by the river; endless wood was available for fuel for the kiln and to use in glazes; and five different types of clay could be dug in the vicinity. Pleydell-Bouverie commissioned her own two-chambered wood-fired kiln, designed for her by Matsubayashi. Mason left the pottery in 1928 shortly before Pleydell-Bouverie was joined by potter Norah Braden, who was quickly established as her new partner and lived at the Mill for months at a time until the breakdown of their relationship in 1936 [].

Figure 3. Photograph of Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie (seated) and Norah Braden at Coleshill, c. 1928–30. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, BHL/9184.

While Pleydell-Bouverie’s removal of herself from the main house at Coleshill did not fundamentally alter the day-to-day running of the estate or challenge the conventions of her family’s daily life at the main house, her choice to create a separate household on the periphery of the estate was a radical one. Moving from a domestic space associated with leisure to one formerly lived in by employees or tenants, associated with production and labour, was unusual, as was her willingness to carry out the dirty and exhausting work involved in running the pottery. From their letters to Leach, Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden appear to have carried out almost all of the day-to-day running of the pottery, including substantial physical tasks such as wedging the clay and packing and unpacking the kiln. In order to fire the kiln, both women slept in shifts on camp beds in order to feed it more than two tons of wood over the course of thirty-eight hours. Their investigations into ash glazes were hugely experimental but also labour intensive. Although estate workers provided the firewood and much of the cut wood and plant material, Braden and Pleydell-Bouverie separated it, carefully burnt it and sieved and rinsed the resulting ash at least four times, in order to gain a small, useable amount. This was then incorporated into a glaze and, after much trial and error, tweaking and adjusting, successful glaze recipes were meticulously noted down by Pleydell-Bouverie. Her undertaking of physical labour formerly associated with men of a different, artisanal, class, as well as her precise and scientific experimentation and note-taking, was, according to Moira Vincentelli, ‘an unspoken but significant statement of resistance to her assigned place in the social structure’.Footnote7

As well as the labour involved in preparing the clay and glazes, there was substantial physical skill required in working the Japanese-style wheel on which Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden threw their pots. Historically, wheel throwing had been viewed as an artisanal occupation rather than a creative act, performed by male labourers of a lower class in the service of male ceramics designers. Throughout the nineteenth century, women had worked in the ceramics industry but in very specific roles. Working-class women had been employed as cheap labour in the industrial production of pottery but were only permitted to carry out basic tasks such as carrying clay, working moulds, glazing, operating potters’ treadles and wheels, and later operating machines such as the jigger and jolley. Such role restrictions ensured that they did not threaten their male counterparts, whose more complex roles were protected by trade unions.Footnote8 Middle-class women had been employed as ‘paintresses’, decorators or fine model makers in order to make use of their supposed ‘natural’ dexterity and affinity with colour, their talent for designing two-dimensional motifs supposedly originating from their skill as homemakers.Footnote9 Studio pottery, however, placed importance on a single artistic mind designing, making and decorating the pot, with special emphasis placed on throwing on the wheel. Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden were some of the first female studio potters to fully master the wheel, ignoring previous concerns about its status and the impropriety associated with women using it, most likely stemming from the ‘unladylike’ seated position required, with legs straddling the wheelbase.Footnote10

Vincentelli further argues that Pleydell-Bouverie’s choice of pottery over other art forms, with its traditional masculine connotations, may be interpreted as ‘a manifest demonstration of an alternative gendered identity’.Footnote11 As demonstrated above, the making of pottery in England had long been associated with men, but it is difficult to gauge the extent to which Pleydell-Bouverie’s choice was intended to demonstrate a differently gendered identity or was an emancipatory attempt to enter a historically male profession. A survey of surviving correspondence shows no hint at either intention specifically, instead revealing Pleydell-Bouverie’s fascination with pottery, determination to work with clay and self-proclaimed lack of interest in going ‘back to living the life of a perfect gent after the first war’.Footnote12

Undoubtedly, pottery was an unexpected choice for an aristocratic woman but not as much as it would have been twenty years earlier when throwing pottery was solely the preserve of working-class men. Arguably, craft-related class-transgression began with the first Arts and Crafts generation, including William Morris and his circle. Zoë Thomas has pithily summarised the male anxiety caused during this period by ‘the persistent associations of the ‘minor arts’ with trade [which] made artists anxious to continue to be associated with the middle classes’.Footnote13 This was no doubt the root of Roger Fry’s observation of, ‘ … a certain social class-feeling … a vague idea that a man can still remain a gentleman if he paints bad pictures, but must forfeit the conventional right to his Esquire if he makes good pots or serviceable furniture.’Footnote14 This anxiety had led to the creation of elite, male-only spaces such as the Art Workers’ Guild, but by the 1920s these concerns held much less sway. By then, Fry and Leach’s philosophising about the wheel and pottery’s popularity among an educated middle class meant that Pleydell-Bouverie’s decision to take it up might be viewed by her peers more as bohemian eccentricity than genuine class-transgression, or a transgression at most from upper to middle class. For the first time, pots were approached from an intellectual position. As Edmund de Waal has noted, the interwar epoch was one ‘when making pots was precious and rarified, the occupation of a middle-class Bohemian vanguard.’Footnote15 Nevertheless, Pleydell-Bouverie’s background created expectations in those who met her. The unlikeliness of someone of her position taking up ceramics was highlighted in a comment by her friend, the potter Michael Cardew. Given her aristocratic background, Pleydell-Bouverie was not at all what he was expecting:

I thought it [her aristocracy] all sounded a bit intimidating: my idea of a potter was that he or she had to be primitive, living like a peasant, close to the ground. But when we actually met, the reality was not alarming at all. I had been expecting someone fragile and over-civilised, very delicate, very ‘Dresden China’. But to my relief I found myself talking to a tall, strong girl, not much older than me, who was built like a peasant, with a peasant’s large and practical hands.Footnote16

It is therefore possible that both women dressed in trousers and a masculine style only while working in the pottery, making this a practical choice to facilitate their work rather than a gendered statement. Interpreting dress worn during this period is complex, as demonstrated by Doan’s work on the range of both masculine and feminine dress available to women during the 1920s and the ambiguity this entailed. Doan argues that we must be careful in reading ‘masculine’ dress as ‘male’:

In the decade prior to the publication of Hall’s novel [The Well of Loneliness], and even for a short time after, boyish or mannish garb for women did not register any one stable spectatorial effect. The meaning of clothing in the decade after the First World War, a time of unprecedented cultural confusion over constructions of gender and sexual identities, was a good deal more fluid than fixed.Footnote19

Although keen to remove herself from some of the strictures associated with country house living, Pleydell-Bouverie did not entirely reject the lifestyle associated with it and continued to take full advantage of her privilege in order to use the main house as a venue to host guests, but on her own terms.Footnote22 Cardew recalled visiting Coleshill and although days were spent in the pottery, everyone dined and bathed in the main house. Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden returned to the Mill to sleep, while he was shown to a room in the upper storey of Coleshill House. But he commented on never being made to feel ‘intimidated or out of place […] even the butler never let me feel the inadequacy of my wardrobe’.Footnote23 A woman was employed to clean and ‘potter’ at the cottage and Pleydell-Bouverie had her own car that could be used for outings, as well as the chauffeur-driven vehicle attached to the main house. Braden especially was unaccustomed to this level of comfort and sophistication, which added to her enjoyment of her life at Coleshill. But in contrast to the main house, Mill Cottage provided privacy. Like many country houses in convenient locations, Coleshill House received a constant stream of visitors, including people known to the family who came to stay or ‘dropped in’ on their way further west or back to London, as well as (according to Pleydell-Bouverie’s cousin Doris) a large number of ‘appreciative and learned visitors’ who ‘were never refused entry’.Footnote24 The latter were not welcome at Mill Cottage – it was not open to the public and work was not sold from there but transported to London to be sold in galleries. Nor was it a maison d’artiste, a semi-public home that showed off the work of artists, such as the homes of some other queer women artists working in this period including Eileen Gray and Romaine Brooks in Paris, or Gluck in London. Mill Cottage was intended to be a refuge from these interruptions, allowing Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden to focus on themselves and their work.

This arrangement at Mill Cottage provided Pleydell-Bouverie with an opportunity to live independently with her partners. Given the ‘negative stereotyping’ of non-heterosexual women that followed the obscenity trial of Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness in 1928,Footnote25 one may imagine that her choice to live separately from the main house was an attempt to avoid this. However, as there is no mention of the censorship trial in Pleydell-Bouverie’s surviving letters from this period, and as she had established the pottery with Mason years prior to the trial, living in Mill Cottage was more likely to stem from a combination of personal and practical factors. There also seems to have been little eyebrow-raising from their immediate circle of friends or from Pleydell-Bouverie’s family, who accepted that she shared her life and homes with women, according with Bourdieu’s argument that ‘the higher up the class scale the more socially constituted differences between the sexes are able to be contravened’.Footnote26 Surviving correspondence from Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden to Leach, detailing their life at Coleshill, hints at no awkwardness between Katharine and her wider, aristocratic family, who regularly welcomed first Mason and then Braden at the main house, included them at mealtimes, and were happy to engage in such familiar association as collecting them from the train station. However, this behaviour differed to that of some of Braden’s middle-class family, who seem to have viewed her artistic work, her relationship with Pleydell-Bouverie, and later, her spinsterhood, with suspicion and embarrassment. In 1954, after the death of her mother (to whom she was devoted), Braden became estranged from her two older brothers and their families and later, her will made no mention of any family members.

But Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden’s arrangement was not unusual in their wider circle, which encompassed other queer men and women. This network centred loosely around Muriel Rose and Peggy Turnbull’s The Little Gallery (1928–39), so-called because of its size, located in a former laundry depot on Ellis Street, off Sloane Street, London. The Little Gallery exhibited and sold traditionally-made objects (such as quilts) by anonymous makers as well as crafts by contemporary artist-craftspeople, including Michael Cardew, who described himself as ‘three-quarters homosexual’, and a number of women in same-sex partnerships such as textile designers and makers Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher, weaver Elizabeth Peacock (who shared her life with farmer Mollie Stobart), and designer and illustrator Enid Marx (whose partner was historian Margaret Lambert).Footnote27 Hilary Bourne, who later became a weaver and a founder of the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft, was an employee of the Little Gallery when she met her partner, theatre designer Barbara Allen. Dense with romantic, friendly, artistic and business connections, this network of queer, female artists and gallerists foregrounded the work of women not connected to the masculine, urban centre of the art world and instead asserted the value and artistic potential of crafts and handmade objects.Footnote28 As well as providing a social network, the Little Gallery created economic opportunities for these craftspeople, some of whom lived rurally, to sell their work to a metropolitan clientele, thereby enabling them to fashion independent creative lives outside of the heteronormative sphere. Like other galleries in London that exhibited and sold the work of Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden, the urban environment was key to publicising, exhibiting and selling work during one of the most severe periods of economic depression of the twentieth century, whereas the rural environment was key to its making.

Much scholarship on artistic women in same-sex relationships during the interwar period has focussed on metropolitan centres as sites of activity, especially Paris, with its connotations of liberality and anonymity. However, from the late nineteenth century onwards, some queer writers and artists instead gravitated towards rural environments in order to live more freely, following an approach articulated by poet Edward Carpenter (1844–1929). Building on the writings of Henry David Thoreau (1817–62), Walt Whitman (1819–92) and William Morris (1834–96) in relation to land and nature, Carpenter combined a ‘back-to-the-land’ approach – an escape from civilization and a return to nature – with early ideas of ‘free love’ and the pursuit of personal relationships that were, ‘free and joyful, healthy and creative, long-lasting or short and always unconstrained by external laws or expectations’.Footnote29 From 1898, Carpenter lived openly with his male partners, and provided a template for others looking to create alternatively-structured households or communities. These included C. R. Ashbee (1863–1942), who considered Carpenter his mentor, and whose Guild of Handicraft sought to establish a cross-class, socialist, homosocial community of artists and craftspeople.

Although the pastoral idyll had long been more commonly associated with masculine same-sex eroticism, the effect of the rural environment in ‘naturalizing’ that which was viewed as ‘unnatural’ held appeal for women too. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of queer women artists and craftspeople established themselves rurally. These included a number of the craftswomen listed above who exhibited at The Little Gallery, as well as designer May Morris and her partner Mary Lobb who lived in Kelmscott, Oxfordshire; writers Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland in Maidon Newton, Dorset, and Vita Sackville-West in Sissinghurst, Kent. Radclyffe Hall lived mostly in London and Rye with her partner Una Troubridge, but her deployment of ‘neo-pastoral conventions’ in her novel The Well of Loneliness (1928) forms the bedrock of her portrayal of her famous female protagonist, Stephen Gordon, who is firmly situated within the rural landscape and the world of the local landed gentry. Stephen loves Castle Morton (a large country house) and the memory of it remains with her long after she is banished from it and moves to the urban centres of London and Paris. According to Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, this is an example of a lesbian author using ‘pastoral literary traditions to develop a reverse discourse that argues for the naturalness of women’s same-sex love relationships and/or the congenital equality of lesbians.’Footnote30 The country house was also central to the life and work of Vita Sackville-West, whose writing, according to Suzanne Raitt, ‘reimagined the natural world as a space in which sexuality could be renegotiated and enjoyed in safety and seclusion.’ Raitt’s assessment of the rural aspect of Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf’s relationship concludes that ‘the locus for the creation of authentic art is the delicate riverside idyll of lesbian desire, innocent of the ugliness of heterosexual anger and oppression.’Footnote31 This identification of the natural environment (a ‘riverside idyll’ no less) as one peculiarly suited to both same-sex relationships and the facilitation of ‘authentic art’ reflects precisely what Pleydell-Bouverie aimed to achieve at Mill Cottage.

The beauty of the estate was familiar to Pleydell-Bouverie but made an impact on those who visited, including critic Ernest Marsh, who noted that ‘a more delightful setting for the production of pottery could scarcely be imagined than the little house adjoining the old disused water-mill situated on the edge of the park … ’.Footnote32 Coleshill was a revelation to Braden, who had been born in Margate and subsequently lived in various London suburbs. It was not only the physical environment, the charming, natural surroundings that made an impression, but the lifestyle and leisure afforded to her while she was there, or as Marsh described, ‘the needful relaxation from the arduous and exacting work associated with pottery making’.Footnote33 At first, Braden expected only to stay at Coleshill for a couple of months in order to make components for her own kiln, which she hoped to build at her mother’s new house, Cobwebbs [sic] in West Hoathly, Sussex. But a closeness formed quickly and she was moved by the care she received from Pleydell-Bouverie (nicknamed ‘Beano’), whose thoughtfulness and attentiveness made a great impression. In March 1928, Braden wrote to Leach that she had had the flu and had been left by herself at the cottage with strict instructions not to move unless it was to go out and sit in the sun. However, on venturing outside she found that Pleydell-Bouverie had left an armchair, footstool and cushions for her, in a picturesque spot by the water:

Beano has done everything in her power to make life happy for the last two months […] This is so typical of her thousand daily humanities. Life here is so peaceful Ricky [nickname for Leach] dear – and would be almost perfect if I could dispel the eternal grey cloud – the prospect of returning home so soon.Footnote34

Although Braden’s letters are filled with rich, descriptive passages, conveying her pleasure in being at Mill Cottage with Pleydell-Bouverie and her reluctance to leave, these sentiments are accompanied by feelings of guilt and descriptions of her selfishness:

Except for a little ‘turning’ [finishing pots on the wheel], I’ve lain here practically the whole day and expanded every fibre and gathered the fullness of such pleasures of this divine leisure. This morning I lay on my back and Beano read aloud. In the afternoon, she wrote – I sewed. […] I’ve been thinking of [‘Peter’] Mason a great deal today and other lonely people and the thousands stiffled [sic] in towns and thinking how lucky and spoiled I am – how selfish. I talk of it with horror everyday to myself – and yet seem to continue just as before.Footnote36

A life without the expected momentous events does not move forwards with the same headlong zeal, rushing from one prescribed achievement to the next – meeting, marrying, reproducing – and instead encourages indulgence and dawdling and miraculous repetition, offering those dissenters from convention an opportunity to stay inside their most heightened, precious moments forever.Footnote37

The period that the two women worked together at Coleshill proved to be the zenith of both of their careers, corresponding as it did with a high point for the wider studio pottery movement in Britain. During this period, in which the distinctions between applied and fine art were least delineated, ceramics were often allied with abstract art and sculpture. During the 1920s and 1930s, handmade ceramics were often divorced from the domestic environment, sold in high-end galleries both on and off Bond Street, and widely exhibited, often in shows alongside works by artists including Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ivon Hitchens, Paul Nash and Ben Nicholson. Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden’s work was exhibited in London by the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society and the National Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers and Potters, and in exhibitions held at galleries including the Little Gallery, Paterson’s, the Zwemmer Gallery (in Paul Nash’s important 1933 exhibition, Artists of To-Day) and The Brygos Gallery. It was frequently favourably reviewed, especially in The Times and was included in museum exhibitions in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent and at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, as well as shown internationally and included in an exhibition of British crafts that toured North America.

Coleshill was key to this success and to their growing reputation. But the estate not only provided the means, equipment and privacy – the conditions – for making ceramics but it is quite literally in the pots too. Along with the clay being dug from the ground nearby and trees chopped down to fuel the kiln (this task carried out by estate workers), more unusually, the plant life on the estate formed the basis of all the glazes, producing a huge range of delicate colours, entirely from and of the natural world ( and ). Ash glazes had been used historically in the creation of East Asian ceramics but Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden’s experimentation broke new ground in the context of twentieth-century Europe. With little to go on other than the volume Manures for Fruit and other Trees (1908) by A. B. Griffiths and some words of advice from potter Nell Vyse (1892–1967), Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden set about creating a range of delicately-hued glazes using ash created by burning plant material available on the estate, including ‘holly, laurustinus, beech, elder, rose, honeysuckle, larch, box, maple, vine, ivy, peat, stone pine [and] nettle’.Footnote40 Far from seeking simply to record the natural world, Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden sought to make it an integral part of their work.

At a time when most other British studio potters were looking to Bernard Leach and his Anglo-Asian style, which took much from Chinese, Japanese and Korean ceramics, Pleydell-Bouverie wrote:

I want my pots to make people think, not of the Chinese, but of things like pebbles and shells and birds’ eggs and the stones over which moss grows. Flowers stand out of them most pleasantly, so it seems to me. And that seems to matter most. […] Don’t run away with the idea that I want to imitate stones or pebbles […] But I do want the reaction of someone who sees my pots to be: ‘That looks natural’.Footnote41

This particular, native connection of Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden’s work was commented upon by, W. A. Thorpe, a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum who published an extensive 1930 article in Artwork on the two women. As well as praising the three-dimensional forms of their pots (significant given that women had until recently been thought incapable of producing ceramic forms), Thorpe identified a particular ‘English’ idiom to their work through the direct connection to landscape and to the flowers that were sometimes displayed in the pots they made. He wrote that ‘the glazes are original because they open the art of pottery to a ceramic expression of English sentiment’, and that they brought indoors ‘a bit of landscape’.Footnote43 Thorpe correctly identified the centrality of the Coleshill estate and ‘English sentiment’ in the work of both Braden and Pleydell-Bouverie. The latter’s enthusiasm for nature, which originated in her rural upbringing on the estate, was made tangible in her incorporation of it in her pots. The materiality of the work was specific to the locus of the estate – Pleydell-Bouverie’s pots were of the place itself and therefore can be read as a celebration of her surroundings and her alternative way of life. They also evidence her wider interest in rural England and its folk traditions including country dancing, in which she participated frequently throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, and can arguably be connected to a broader, increasing artistic appreciation of English landscape during the interwar period.Footnote44

Pleydell-Bouverie’s appropriation of the estate for personal, creative means differs from traditional narratives of aristocratic women interacting with their estate in order to ‘enhance the prestige and cultural capital of their families’.Footnote45 These gendered narratives usually centre on the creation or transformation of land, which even if done as a means of self-expression has been interpreted as a nurturing act and a contribution to future generations (land being central to the inheritance). Conversely, Pleydell-Bouverie’s focus on the present, rather than the future, and her use of the plant life on the estate as a material resource, with a view only to how it would benefit her own work and artistic practice, suggests an indifference towards future inheritance or children, in reproductive futurism, that speaks to her non-heteronormative lifestyle.Footnote46 If, as Sara Ahmed claims, ‘the promise of the family is preserved through the inheritance of objects’ (in this case, of the estate), Pleydell-Bouverie’s lack of interest in its future speaks to her conscious breaking of this familial promise, severing the link between family and estate, and focussing her labour and energies on her own artistic output rather than towards any domestic purpose.Footnote47 In this sense, her pots embody Pleydell-Bouverie’s queering of the estate and her prioritisation of her role as an artist over that as a female aristocrat.

One could argue that these actions, coupled with the sale of the house and estate by Pleydell-Bouverie and her sister Molly in 1945, accord with Peter Mandler’s assessment of many landowners during the interwar period who voluntarily ‘sold up’ in order to release funds and live more comfortably elsewhere, ‘indicating a deeper estrangement from traditional roles’.Footnote48 However, although Pleydell-Bouverie may have felt estranged from her traditional role within an aristocratic family, close reading of the details of the sale of Coleshill, undertaken by Karen Fielder, reveals a more complex situation. In her thesis, Fielder argues,

The archives suggest that Mary Pleydell-Bouverie and her sister [Katharine] felt a sense of duty to ensure the preservation of Coleshill for posterity even in the absence of heirs […] Arguably the sisters would have been keen to offload the house, and relief from its financial burden cannot have been far from their minds, but they were nonetheless conscious both of its architectural significance and of its importance as an emblem of family heritage and dynastic longevity.Footnote49

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are no studio pots more ‘country house’ than those created by Pleydell-Bouverie, the granddaughter of an Earl, using natural materials from an estate long cultivated by labourers working in service to the family. However, by using Coleshill estate for her own means, by building, establishing and occupying her own spaces and forging her own, non-heteronormative path, Pleydell-Bouverie disrupted the expectations placed on her as an aristocratic woman and her role in the creation of family and lineage. Instead, using the economic and social privilege afforded to her, she pursued her own agenda and created a queer life devoted to art and nature. Arguably, rather than a family estate or descendants, it is Pleydell-Bouverie’s pots, stamped with her maker’s mark, and her glaze recipes, that stand as her legacy.

The legacy of Mill Cottage is less straightforward. Coleshill House was mostly destroyed by a fire in 1952 and its ruins subsequently razed to the ground. Today, the remaining estate, including the Mill, is cared for by the National Trust. Inspired by Alison Oram’s case studies of the heritage industry’s presentation of sexuality in relation to historic houses,Footnote50 I revisited the extensive photographs and notes I made on a visit to Coleshill Mill on 8 September 2019, to ascertain the visibility of Pleydell-Bouverie’s legacy and ‘queering’ of the estate. On that day, the Mill was open to visitors and staffed by enthusiastic, male volunteers, who were keen to explain the history of the estate, the building and the mill workings, including the typology of the water wheel, the technicalities of how flour was produced and how the Mill had been brought back to working order in 2005. These volunteers spoke only of the functionality of the Mill as a space for labour, as well as a site of technological complexity and as one of the ‘most unaltered working watermills in the country’. This information was presented on one of a series of laminated information sheets, perhaps produced by the volunteers themselves. These chronological sheets detailed the families who had lived and worked there since the late 1600s and explained Pleydell-Bouverie’s use of the Mill, describing the new water wheel she commissioned in 1922, and the building of the kiln – focussing predominantly on the physical fabric. No mention was made of Mason or Braden. A separate interpretation panel, part of the formal curatorial presentation of the Mill (printed onto board and with National Trust branding) more explicitly celebrated Pleydell-Bouverie’s achievements as a ‘pioneer of studio pottery’. But again, Mason was omitted from the narrative and Braden was mentioned only in the following brief statement:

She [Pleydell-Bouverie] was later joined by fellow potter, Norah Braden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helen Ritchie

Helen Ritchie is Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Applied Arts at The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. She is also a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge, researching the studio ceramics of Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie (1895–1985) and Norah Braden (1901–2001). She writes and lectures widely on British studio pottery, contemporary craft and European design post–1850, and has curated a number of exhibitions, often in collaboration with contemporary artists. She is the author of Designers and Jewellery 1850–1940: Jewellery and Metalwork from The Fitzwilliam Museum (2018).

Notes

1 ‘Introduction’ in Women and the Country House in Ireland and Britain, ed. Terence Dooley, Maeve O’Riordan and Christopher Ridgway (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2018), 10.

2 Both women appear on the periphery of full-scale biographies of their better-known male peers, Bernard Leach and Michael Cardew, and were perceptively described in the autobiographies of these men. See Emmanuel Cooper, Bernard Leach: Life & Work (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003); Tanya Harrod, The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew, Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012); Bernard Leach, Beyond East & West (London: Faber and Faber, 1978); Michael Cardew, A Pioneer Potter: an Autobiography (London: Collins, 1988).

3 Crafts Study Centre, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie (Bath: Crafts Study Centre, 1980); Crafts Council, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie: A Potter’s life 1895–1985 (London: Crafts Council in association with the Crafts Study Centre, Bath, 1986).

4 For Pleydell-Bouverie’s glaze recipes see Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, ‘The Preparation of Ash for Stoneware Glazes’, Pottery Quarterly 6, no. 22 (1959); ‘Wood and Vegetable Ashes in Stoneware Glazes’, Ceramic Review nos 5 and 6 (1970); ‘Ash Glazes’, Ceramic Review, no. 51 (1978).

5 Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Berkshire (London: Penguin, 1966), 118.

6 ‘Country Homes: Coleshill House, Berkshire’, Country Life, no. 383 (7 May 1904).

7 Moira Vincentelli, Women and Ceramics, Gendered Vessel (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 222.

8 Cheryl Buckley, Potters and Paintresses: Women Designers in the Pottery Industry 1870–1955 (London: The Women’s Press, 1990), 21–37.

9 For an overview of the role of women in the British ceramics industry, see Buckley, 1990, chapters 1–3. Further literature is also available on individual decorators, for example, Colin Andrew, ‘The Lewis Girls of Doulton Lambeth’, Journal of the Northern Ceramic Society, no. 34 (2018): 163–84.

10 There were a small number of other women in England who had learnt to throw previously, but none achieved the success of Pleydell-Bouverie and Braden. Hannah Barlow (1851–1916) made Art Pottery for Doulton and unusually threw her own pots as well as decorating them – presumably she was taught by one of the male throwers also working for Doulton. Generally, throwing tuition for women was hard to come by prior to 1916. Other early women studio potters who threw on the wheel include Dora Lunn, Frances Richards, Dora Billington, Denise Wren, Sylvia Fox Strangways and Sybil Finnemore.

11 Vincentelli, Women and Ceramics, 145.

12 Letter from Pleydell-Bouverie to Enid Marx, 27 September 1981, from the archive of Enid Marx, Archive of Art and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum, AAD/2007/3/185, part 2.

13 Zoë Thomas, ‘Between Art and Commerce: Women, Business Ownership, and the Arts and Crafts Movement’, Past & Present 247, no. 1 (May 2020): 151–96, 160.

14 Christopher Reed, Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture, and Domesticity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 114.

15 Edmund de Waal, Bernard Leach (London: Tate Gallery, 1997), 68.

16 Michael Cardew, ‘St. Ives and Coleshill Days’, in Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, (Bath: Crafts Study Centre, 1980), 10.

17 Laura Doan, Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture (New York; Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2001), 119.

18 See Bonnie White, ‘“A Better England”: Women’s Agricultural Labour and the National Association of Landswomen, 1919–1923’, Agricultural History Review 69, no. 2 (December 2021): 255–73.

19 Doan, Fashioning Sapphism, 96.

20 Ibid., 110.

21 Harrod, The Last Sane Man, 61.

22 For more on socialising in country houses during the interwar period see Adrian Tinniswood, The Long Weekend: Life in the English Country House between the Wars (London: Jonathan Cape, 2016), chapter 14.

23 Cardew, A Pioneer Potter, 77.

24 Crafts Council, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie: a Potter’s Life 1895–1985, 14.

25 Bridget Elliott, ‘Art Deco Hybridity, Interior Design, and Sexuality between the Wars Two Double Acts: Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher/ Eyre de Lanux and Evelyn Wyld’, in Sapphic Modernities: Sexuality, Women and National Culture, ed. Laura Doan and Jane Garrity (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2007), 111.

26 Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction, A Social critique of the Judgement of Taste (London; New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), 382–83, quoted in Vincentelli, Women and Ceramics, 145.

27 Cardew reference from Notes for Autobiography, vol. II, p. 993, Archive of Art and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum, AAD/2006/2/2/19, quoted in Harrod, The last sane man, 385.

28 For more on this network see Lotte Crawford, ‘Muriel Rose and Peggy Turnbull’s The Little Gallery: Elevating the Profile of Modern Craft through Interwar Shop Displays’, The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 46 (2022): 102–15. For The Little Gallery see Muriel Rose: a modern crafts legacy, ed. Jean Vacher (Farnham: Crafts Study Centre, 2006).

29 Jan Marsh, Back to the Land, The Pastoral Impulse in England, from 1880 to 1914 (London: Quartet Books, 1982), 22.

30 Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, ‘Introduction: A Genealogy of Queer Ecologies’ in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, ed. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2010), 24.

31 Suzanne Raitt, Vita and Virginia, The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 16.

32 Ernest Marsh, ‘Studio Potters of Coleshill, Wilts. Miss K. Pleydell-Bouverie and Miss D. K. N. Braden’, Apollo, no. 38 (December 1943): 162–64, 162.

33 Ibid.

34 Letter from Norah Braden to Bernard Leach dated 30 March 1928. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, no. 2425.

35 Nina Lübbren, Rural artists’ colonies in Europe 1870–1910 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 79.

36 Letter from Norah Braden to Bernard Leach dated 15 July 1928. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, no. 2468.

37 Rebecca Birrell, This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century (London: Bloomsbury Circus, 2021), 155.

38 Letter from Norah Braden to Bernard Leach, undated and fragmentary. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, no. 2479.

39 Tanya Harrod, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th century (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 260.

40 Crafts Council, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie: a potter’s life 1895–1985, 17.

41 Letter to Bernard Leach written 29 June 1930. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, no. 2500.

42 Letter to Bernard Leach written 17 December 1932. From the papers of Bernard Leach at the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, no. 2513.

43 W. A. Thorpe, ‘English Stoneware Pottery by Miss K. Pleydell-Bouverie and Miss D. K. N. Braden’, Artwork 6, no. 24 (Winter 1930), 260.

44 For a summary, see Frances Spalding, The Real and the Romantic: English Art between Two World Wars (London: Thames & Hudson, 2022), chapter 4.

45 Dooley, O’Riordan and Ridgway, Women and the Country House in Ireland and Britain, 11.

46 For more on reproductive futurism, see Lee Edelman, No Future Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2004).

47 Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2010), 46.

48 Peter Mandler, The Fall and Rise of the Stately Home (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 242.

49 Karen Fielder, ‘X’ Marks the Spot: The History and Historiography of Coleshill House, Berkshire (University of Southampton: unpublished PhD thesis, 2012), 198.

50 Alison Oram, ‘Sexuality in Heterotopia: Time, Space and Love Between Women in the Historic House’, Women's History Review 21, no. 4 (2012): 533–551.

51 Ibid., 547–48.