Abstract

The co-production of resilience in European urban neighbourhoods is explored based on the experiences from a case study. Within the current ‘resilience imperative’, co-production processes involving multiple stakeholders can be a key factor for increasing cities’ resilience. Co-produced resilience processes are more successful when embedded in collaborative forms of governance such as those associated with urban commons and when fulfilling needed roles with a community. Through the application of the R-Urban approach in a neighbourhood of Colombes (near Paris), the co-production of a commons-based resilience strategy is described. This involved a group of designers as initiators and a number of citizen as stakeholders of a network of civic hubs. The specific strategies involving a participatory setting, collective governance aspects and circular economies are analysed in the light of co-production theories and practices. Internal and external challenges are identified within the implementation process. The nature of conflicts and negotiations in this co-production approach are discussed, and the role of the architects/designers as agents within the process is investigated. Reflections from this example are provided on the limits and promises of this approach and the lessons learned from R-Urban for collaborative civic resilience.

Introduction

Given the unknown and unpredictable effects of climate change (IPCC, Citation2014) and the multiple challenges of resource depletion, loss of welfare and economic crises, many current ways of living are not resilient. Hazards and crises precipitated by the impacts of climate change will become increasingly frequent and severe. Cities will need to find ways to adjust and thrive in these rapidly changing circumstances as a ‘resilience imperative’ (Lewis & Conaty, Citation2012).

Resilience theory was first introduced in the 1960s–70s as an area of ‘new ecology’ (Holling, Citation1982). It was then further developed across disciplines, and subsequently entered the mainstream academic discourse via ‘social–ecological resilience’ with a focus on ‘socio-ecological systems’ (Folke, Citation2006). In the last few decades, definitions of resilience have proliferated in many different fields, i.e ., physics, ecology, business studies, psychology, geography, social science aspects of urban and regional planning (e.g., Godschalk, Citation2003; Gunderson, Citation2000; Holling, Citation1973; Shaikh & Kauppi, Citation2010; Timmerman, Citation1981; Werner, Citation1995). This has led to a deeper understanding of the conditions required by complex socio-ecological systems to thrive with uncertainty and unpredictable change. Sustainability is traditionally associated with development and growth based on a dynamic equilibrium (Botkin, Citation1990; Scoones, Citation1999; Zimmerer, Citation1994). The resilience discourse has challenged (and updated) the discourse on sustainability due to its emphasis on uncertainty and disruption. Resilience discourse has introduced a more dynamic perspective on change processes, addressed through subsequent notions such as ‘adaptative capacity’, ‘transformation’, ‘transition’ (Brown, Kraftl, & Pickerill, Citation2012; Folke et al., Citation2010; Walker, Holling, Carpenter, & Kinzig, Citation2004), and ‘resourcefulness’ (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013). Resourcefulness is a relatively new concept that addresses the necessity to identify, make available and redistribute resources of space, knowledge and power across local actors and communities to improve resilience. The notion of resourcefulness situates resilience in a more positive light, relating it to the agency of empowerment of the community

Resilience and empowerment

The resilience discourse on adaptation and mitigation has also been adopted by major international development, research and policy institutions, such as the Resilient People, Resilient Planet document by the United Nations (Citation2012), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the World Bank (Welsh, Citation2014). More recently, the policy discourse on resilience has helped to shift the focus from the idea of mitigation to include more emphasis on adaption to climate change (Nelson, Citation2014). European Union directives tend to consider resilience mainly from technological and environmental perspectives (i.e., Critical Information Infrastructure Protection (CIIP), European Public Health Alliance (EPHA)), with little emphasis on social, cultural and political dimensions (Hornborg, Citation2009) or the ‘bottom-up’ practical perspective (Vale, Citation2014). This policy framework has prompted research in the area of engineering solutions that tackle ‘emergency’ aspects rather than ‘empowerment’ aspects of resilience processes (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013).

However, the empowerment aspect addressed in the resilience discourse has been adopted by national and local policy to some extent, particularly in the context of the recession following the global economic crisis of 2008. ‘Community resilience’ in these policies focuses on community self-reliance and empowerment by reducing the state contribution and encouraging volunteering and community activity (Office, Citation2011). Although some governments are starting to recognize the vital impact of community empowerment on austerity economy, and promote supporting policies (e.g., the Big Society flagship programme of the UK government; Cameron, Citation2011; Government, Citation2010), little research has been done on the challenges communities have in achieving long-term resilience. Research is particularly needed to understand and analyse the evolving and aligning strategically community resilience projects in relation to other initiatives, support frameworks and top-down policies in order to produce convergent policies and actions with large-scale impact.

Resilience supporting the political status quo

Despite a widespread use across a range of fields and sectors, the concept of resilience is significantly under-theorized in terms of power, conflict, contradiction and culture (Hornborg, Citation2009; Wilkinson, Citation2012). Resilience is thus put forward as a politically neutral term, which maintains a simplified rhetoric of ‘sustainability’ and offers technocratic (adaptive management) solutions, arguably framed within, and using pervasive, capitalist logic and vocabulary (Welsh, Citation2014).

Resilience theory is also seen as offering a scientific vocabulary for market-based approaches to climate change by framing adaptive change in terms of ‘leveraging’ social and natural capital (Nelson, Citation2014). Furthermore, by encouraging the idea of active citizenship, whereby people and communities take responsibility for their own social and economic well-being rather than relying on the state, resilience has been also associated with normalized neoliberal ideology (Joseph, Citation2013). This is illustrated by the ‘Big Society’ project, with its focus on localism and community as a way of legitimizing the dismantling of the welfare state and the provision of public services (Cretney & Bond, Citation2014).

In a similar manner, ‘top-down’ resilience strategies, as defined externally by experts and state agencies, place the onus on individuals, communities and neighbourhoods to become more adaptable to various external threats. However, this approach is paradoxical because instead of empowering communities, it reproduces wider social and spatial inequalities (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013). Indeed, some argue that resilience represents the preferred means of maintaining business as usual (Diprose, Citation2015), promoting ‘responsibility without power’ (Peck & Tickell, Citation2002, p. 386), and producing active citizens and institutions whose purpose is to maintain the status quo rather than challenge it (Welsh, Citation2014).

Commoning resilience

In parallel to this neoliberal framing of resilience, groups that challenge such dominant societal structures have also been mobilizing resilience strategies within a different ideological approach (e.g., Transition Towns movementFootnote1). Aspects of adaptive capacity and transformation have been used to strengthen local communities and promote anti-capitalist activist projects rather than maintaining dominant economic and political systems (Cretney & Bond, Citation2014; Hopkins, Citation2010; Goldstein, Citation2012). Movements such as Transition Towns, or Incredible Edible, which act in this manner, have been extensively studied (Barnes, Citation2014; Connors & McDonald, Citation2011; Feola & Nunes, Citation2014; Mason & Whitehead, Citation2012), but little research has been done on the link between these grassroots resilience initiatives and the ‘new commons’ movement, which is concerned with communal management of land and resources as a project of resistance to privatization and globalization (Brown et al., Citation2012).

The term ‘commoning’ has been coined by historian Peter Linebaugh (Citation2009). His work describes how people live in close connection to the commons over time. The term, which turns a noun into a verb, refers to the social process that creates and reproduces the commons (An Arkitectur, Citation2010). It is also grounded in Ostrom’s earlier work on the community governance of common pool resources (Ostrom, Citation1990) and the further development of a commons-focused interdisciplinary political theory (De Angelis, Citation2007; Bollier, Citation2014; Capra & Mattei, Citation2015; Negri & Hardt, Citation2009; Stavrides, Citation2016), which marked the ‘return of commons’ (Gutwirth & Stengers, Citation2016) in the academic and political discourse.

This notion of ‘return of commons’ questions the current democratic foundations and the dual regime of public/private ownership, reclaiming commonly produced values as a new revolutionary project. Grassroots resilience movements are producing new social and economic values and have an important role in ‘re-commoning’ the assets necessary for a community to sustain collective activities in the neighbourhood and beyond (Brown et al., Citation2012). These movements contribute to the new political–economic agenda of ‘commons’, within a broader process of connecting and expanding the fissures in the logic of capitalism by proposing new alternatives (Holloway, Citation2010). The study of commoning related to resilience movements combines contemporary discussions on resilience with those on co-produced democracy (Negri & Hardt, Citation2009; Harvey, Citation2014; Hirst, Citation1993; Bawens, Citation2015). This can offer radical possibilities for resilience theory to go beyond its neoliberal framing (Welsh, Citation2014) and forge new understandings of the world as an unstable and crisis-prone social–ecological economy (Nelson, Citation2014).

At present, little research has been done on the nature of processes of collaboration and co-production entailed by the practices of different governance models, the multiple actors involved and the diverse methods used in the movements and activities mentioned above (Goldstein, Citation2012). Performative accounts of such commons-based resilience can usefully explore the gap between theory and practice (Wagenaar & Wilkinson, Citation2013; Radywyl & Biggs, Citation2013).

This paper focuses on one such example by trying to understand the processes and challenges within the implementation of a participative strategy of civic resilience through a network of urban commons. The case study is situated in the suburban town of Colombes, north-west of Paris.

The paper is structured as follows. First, the problematics of co-produced resilience are contextualized within current resilience theory. This helps to explain the importance of empowerment and commoning within neighbourhood resilience. Then the concept of co-production is introduced in the light of commons-based resilience theories and practices. The next section analyses the nature of co-production within the R-Urban strategy. This strategy consists in establishing a network of civic hubs that host and support resilient practices, tools and spaces for local actors. The strategy is based on three main principles: Networking, Participation and Local ecosystems. This is followed by a section analysing the methodology of co-producing resilience in the implementation of R-Urban in Colombes, which is taken as case study. The results of this implementation are then discussed with a focus on the social, economic and ecological benefits and the quality of the governance process within R-Urban in Colombes. The penultimate section identifies specific internal and external challenges of the project around issues of governance, sustainability of processes and structures, legal and institutional support, and access to space. The paper concludes with a critical reflection on the results of this approach and the lessons that can be learnt from this example of collaborative civic resilience, formulating a set of recommendations for practitioners and policy-makers, as well as for further research in the area.

Co-production

The term ‘co-production’ was originally defined in the late 1970s by political economist Elinor Ostrom as ‘the process through which inputs used to produce a good or service are contributed by individuals who are not “in” the same organization’ (Ostrom, Citation1996, p. 1073). Ostrom related co-production with resilience and commons, stressing the importance of collective governance in holding these aspects together (Ostrom, Citation1990).

More recently, the term ‘co-production’ has been deployed in public services policy, particularly after the global economic crisis of 2008, in order to describe a more effective and cost-efficient transformation through the involvement of users in the design and delivery of these services (Boyle & Harris, Citation2009). However, this particular concept of co-production can be used to cover the withdrawal of public services, and marginalize the goal of shifting power relations between stakeholders involved with services and their production (Petcou & Petrescu, Citation2015).

Within academia, critics such as Freire (Citation1970) have highlighted the need for counter-hegemonic approaches to knowledge construction in oppressed communities in order to challenge the dominance of more powerful interests and perspectives. Ethical and political legitimacy of decisions is also weakened if the voice of affected people is absent in the making of those decisions (Young, Citation1990). In this context, deeper engagement with those being ‘researched’ is encouraged as part of achieving a ‘more open and democratic process of knowledge production’ (Brock & McGee, Citation2002, p. 8). This is particularly important when producing knowledge for sustainability and resilience (Pohl et al., Citation2010; Polk, Citation2015) because resilience requires multi-agency responses and partnerships between diverse groups (Trogal & Petrescu, Citation2015).

Engaging with multiple stakeholders, such as researchers, practitioners and communities experimenting with ways of implementing resilience on the ground, is arguably key for a successful process (Beilin & Wilkinson, Citation2015; Boyd & Juhola, Citation2014; Cretney, Citation2014; Robards, Schoon, Meek, & Engle, Citation2011). More broadly, the term ‘stakeholder’ has been used to describe various actors, human as well as non-human, participating in, and affected by, an environmental issue (Vigar & Healey, Citation2002). This level of multi-stakeholder engagement in co-producing resilience has to be rooted in a political ecology standpoint, and requires ideas, tools, space, time and agency if it is to succeed (Maguire & Cartwright, Citation2008; Cahn, Citation2000; Robbins, Citation2004). A co-production approach to resilience needs indeed to enhance the ‘capability to act’ (Sen, Citation1999) of as many as possible.

Co-production of resilience: the R-Urban strategy

The R-Urban model has been developed by atelier d’architecture autogérée (aaa), an interdisciplinary research and design practice based in Paris.Footnote2 Researchers and architects worked together with other public and civic actors to design and build infrastructure for the co-production of resilience (Borne, Citation2012). This infrastructure is in the form of a network of civic hubs that host and support resilient practices, tools and spaces for actors and activators (R-Urban, Citation2014).

The R-Urban model follows previous models of resilient neighbourhood development, such as Howard’s (Citation2013 [1889]) Garden City (1889) and Geddes’s (Citation1915) Regional City and the Transition Town (Hopkins, Citation2008). However, R-Urban is not a direct application of theory, Instead, it works through an iterative and exploratory practice and a theoretical strategy that constantly inform and re-inform each other.

R-Urban follows the eco-urbanism turn in urban planning (Rohe, Citation2009) by engaging with the issues of ‘resilient cities’ (Vale, Citation2014) at the key scale of the neighbourhood. The choice of this scale can actively enable the proactive engagement of local residents in resilient processes. The current discourse on sustainable neighbourhood development in the Northern hemisphere tends to concentrate on green technologies, strategies for smart and efficient use of resources, carbon footprinting and low-carbon development. It primarily pays attention to climate resilience by verifying performance using assessment tools with the aim of enhancing competition among developers and fostering innovation (Sharifi, Citation2016). However, little research has been done on the different stakeholders involved in the processes that projects such as R-Urban adopt at the neighbourhood level, the influence of market forces, the issues in achieving social equity, and the building of diverse and inclusive communities active in resilient transformations (Holden, Li, & Molina, Citation2015).

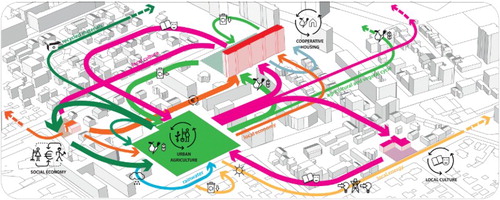

The R-Urban strategy adopts a pluralist approach that provides platforms for various stakeholders to participate in the planning and decision-making process (Sharifi, Citation2016). It does this through the creation of a network of citizen projects and grassroots organizations around collective civic hubs hosting economic and cultural activities and productive practices that engaged with local resources and contributed to increasing resilience. This includes activities and places for urban agriculture, recycling and reuse, community energy production, water and energy consumption reduction and community economies. The hubs are key elements for providing the infrastructure to enable change and offer space, training and capacity building for resilient practices to emerge and strategically connect to each other. These civic hubs also act as ‘urban transition labs’ (Nevens, Citation2012) and enhance the ‘capability (of the community) to act’ – an essential condition for achieving resilience (Sen, Citation1999). The network functions through locally closed systems starting at the neighbourhood level with the potential to scale up at the city level.

Unlike other top-down regeneration strategies facilitated by external managerial structures, in R-Urban the researchers, architects, designers and planners act as initiators, facilitators, mediators and consultants within a ‘pluralist’ approach that provides a platform for wider participation. This can result in a more effective and sustainable implementation, which allows non-specialists and ordinary citizens to rapidly participate in a co-production process. The strategy is conceived as a process to physically transform an urban context. This contributes to the social and political emancipation of those living and acting in this context; enabling them over time to become more ecologically, economically and politically affluent. Citizens are encouraged to change the city by changing their way of living and working in it (Harvey, Citation2008). R-Urban attempts to avoid market speculation by proposing alternative funding, based on a combination of institutional support for implementation, public and civic investment as well as self-funding for running costs, and by putting in place cooperative management structures.

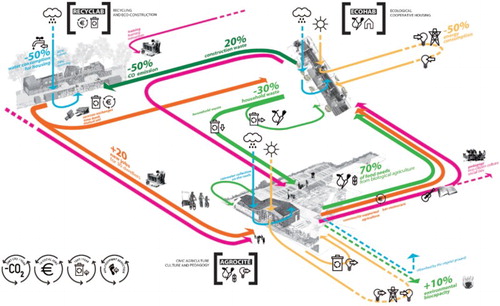

The hubs and their local ecological systems constitute a form of the urban infrastructure that can contribute to a wider ecological transition in neighbourhoods, understood as a relational process rooted in new collaborative social and economic practices. The R-Urban hubs act as prototypes for new ways of building and managing the neighbourhood and demonstrate the positive impacts of ecological transition. Together with a reactivated local community, a number of ecological/environmental parameters were also directly improved through the way in which the hubs were conceived and functioned, as shown in the next section ().

The measurement of such positive impacts is important for prototyping models of resilient neighbourhoods (Mapes & Wolch, Citation2011). Usually these impacts are used to define the market value of a neighbourhood (Sharifi, Citation2016). In the case of R-Urban, the positive impacts are directed to the local citizens themselves in terms of diversity, modularity, social capital, innovation, overlap, tight feedback loops, ecosystem services (Lewis & Conaty, Citation2012), redundancy, connectivity, continuous learning and experimentation, high levels of participation, and polycentric governance (Biggs et al., Citation2012). These processes are captured in the three main principles of the R-Urban strategy.

Figure 1 R-Urban-predicted effects in different urban sectors

Networking

The R-Urban strategy established the conditions for resilience networks and initiatives to emerge in a neighbourhood through a variety of active individuals and local organizations becoming stakeholders in the R-Urban collective hubs, with civic support. These networks valorize the resourcefulness of neighbourhoods (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013), and help produce a more even power distribution within the regeneration process as drivers for community resilience (Hopkins, Citation2008). Collective physical assets – the hubs – make the network visible and anchor the feedback loops in this territory.

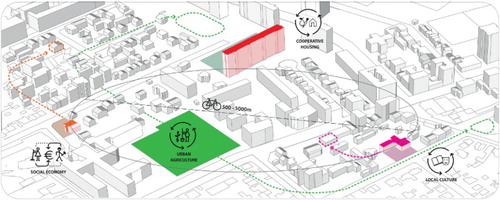

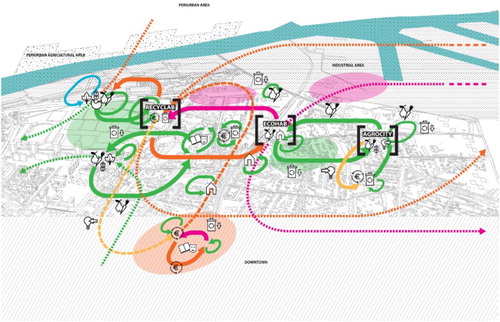

Temporary available spaces are negotiated and made available for mid- or long-term use for R-Urban activities, including vacant sites for urban agriculture, recycling activities and housing. There are further plans for existing buildings to host cultural and productive activities, social housing estates to be transformed into co-housing estates involving the inhabitants in the collective management and maintenance of the estate. These temporarily used plots need to be controlled and governed by citizens to prevent them becoming drivers for market intervention (Blokland & Savage, Citation2008). In R-Urban each civic hub is flexibly connected to a small local network and at the same time is part of the wider R-Urban network, enabling an open system of diverse hubs and productive practices to emerge ().

Participation

R-Urban valorizes the valuable social capital existing in neighbourhoods. It achieves this by enabling all citizens who choose to become involved to participate fully in the implementation of the strategy. This includes participating in events and training programmes, to developing their own activities, and supporting and running the hubs. Citizens are thus not only participants but also agents of innovation and change, generating alternative social and economic organizations, collaborative projects and shared spaces, producing new forms of commons. The new types of jobs, skills and specialisms emerging from this process allow a third sector of collaborative green services in the area of environmental management (Wong, Wong, & Boonitt, Citation2015) and diverse community economies (Gibson-Graham, Cameron, & Healy, Citation2013) to emerge ().

Local ecosystems

The R-Urban hubs generate local ‘ecosystems’ of services and products that connect existing and emerging civic projects and practices. Residents are encouraged to buy local products and also to create local products. These activities provide the basis of an urban metabolic system within the neighbourhood (Castán-Broto & Allen, Citation2011; Ferrao & Fernandez, Citation2013; Douthwaite, Citation1996; Rapoport, Citation2011). The emerging local circular economy (Andrews, Citation2015; McKinsey & Co., Citation2012) is managed by local actors to provide social, ecological and economic improvements for the neighbourhood.

Unlike Industrial Ecology (Tibbs, Citation1992) or Cradle to Cradle (Braungart & McDonough, Citation2002) marketized technocentric approaches, R-Urban hubs are run by citizens to maintain an ecology of local practices. The urban metabolic system thus becomes a tool for community resilience and is a form of commoning in itself. The R-Urban spatial design processes facilitate the activity of citizens through the democratic governance of a commons associated with concrete hands-on action as a catalyst for urban transformation, innovation and creativity. The eventual aim is to develop long-term impact through the development of socio-ecosystems at the local, regional and international scales to facilitate new ‘commons’ within a wider collective urban resilience movement ().

R-Urban methods

The suburban town of Colombes, near Paris, was selected as the first area for developing the R-Urban strategy. It has a mix of private and council estates housing 84,000 residents. It has several social issues (e.g., youth crime, typical of large-scale dormitory suburbs combined with a consumerist, car-dependent lifestyle typical of more affluent suburbs). Despite a high unemployment rate (17% of the working-age population), Colombes has a high number of local organizations (about 450) and a very active civic life ().

The implementation of the R-Urban strategy in Colombes took seven years. As an ‘exemplary’ case by ‘the force of its example’ (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006), the process was useful for generating and testing R-Urban as a potential commons-based resilience strategy for other suburban towns in Europe.

The research methods were developed through practice by aaa working with a wider interdisciplinary research team acting as a think tank. The original initiative was started by aaa in 2008 and subsequently developed into an action research project through a series of funded activities. These included international exchanges between R-Urban stakeholders and actors in similar projects in Europe and beyond to help develop the co-production methods.

The co-production process including the conception, building and governance of a network formed around three civic hubs. This strategy involved different actors (academic, public and civic) in a two-fold co-production process:

co-production of a resilient context, through collaborative mapping, design and building

co-production of practices of resilience through circular economy, ecological systems and civic governance

Co-producing a resilient context

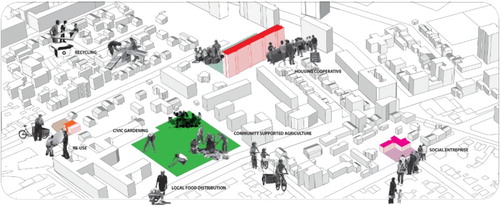

In 2009 aaa contacted representatives of Colombes Municipal Council, including the mayor and applied for funding to implement the R-Urban strategy, with the municipality agreeing to act as partner. A coordination team was formed that included aaa as the lead research team, municipal departments and council representatives. From 2011 to 2015, the project involved the design and building of three hubs – Agrocité, Recyclab and Ecohab – and aimed to create a civic network around them. Each hub aimed to provide complementary facilities: housing, urban agriculture and local culture, recycling and eco-construction to enable citizen-run services and local economic and ecological systems ().

A R-Urban executive team was formed with emerging stakeholders and representatives of the municipality. The European Union funding programme informed the co-production process through formal assessment sessions and feedback on the implementation of the project. Residents were recruited via self-interest in the project at the outset through a series of debates and workshops organized by aaa in Colombes. The executive team was dissolved after the local elections as a result of the change in local politics and the withdrawal of the municipality from the project partnership. The hubs have nevertheless continued to be effectively self-governed by stakeholders, users associations and aaa.

Appropriate locations within available plots in the city were located using a participative mapping process that shortlisted three locations for the first three hubs. This involved collective discussions on land availability and accessibility to decide the location and programming of the hubs ().

Consequently, the city’s planning department identified three sites owned by the city that could be used for the development of the three proposed hubs. Two of the hubs – Agrocité and Recyclab – were subsequently developed and built over two years, 2011–13. Following the change of municipal representation after local elections in 2014 the development of the third hub – Ecohab – was cancelled due to the local authority withdrawing the available municipal site ( and –).

Table 1 Agrocité, Recyclab and Ecohab functions (2015)

Co-producing circular economy, ecological systems and civic governance

According to Ostrom, collective governance is key for the resilience of commons as it involves an ‘agreement’ and a ‘shared concern’ not to destroy the resources on which all members of the community depend (Citation1990). The R-Urban governance strategy is based on a multipolar network involving local and regional actors, formed around the various nuclei of activities that animate forms of exchange and collaboration. Each hub is thus proposed as a commons organization as part of a mutual coordination platform that brings together various entities. R-Urban is conceived as an actor network as described by Latour (Citation2005) in which both humans and non-humans (hubs, materials, devices, frameworks, regulations) have agency.

The R-Urban hubs were designed to set up local circular economies in the neighbourhood using seed funding to construct physical infrastructure (the hubs) and provide development and training courses.

This aim of the initial investment was to enable the emergence over time of a diversity of small economic practices:

gift economies (voluntary or solidary)

material (swaps, loans, barters) and non-material exchanges (knowledge and skills, time)

collaborative economies

monetary economies

These diverse economies are an important asset for a commons-based economic transition (Gibson-Graham et al., Citation2013).

The hubs are also conceived as nodes of an ecological metabolic system emerging in the neighbourhood. Within the hubs, organic waste is collected from the neighbourhood and composted for urban agriculture and a local heating system; rainwater is collected and grey water filtered and reused; waste is recycled or reused; and energy is produced locally. The common pool of resources is visible and circular, involving actively all R-Urban members in its reproduction.

The hubs were deliberately created as non-profit associations. Any common benefit would be reinvested and distributed across the project to enlarge the pool of physical and social resources and the commoning process in general.

The functions of the hubs were not pre-established but were meant to emerge slowly according to available skills and implications. Participants were involved in co-producing over time the programme of the hub, which is conceived as an open system. Each of the proposed activities or emerging practices is governed by the group participating in the co-production of these dynamic and resilient systems in order to evolve rhizomaticaly, transforming and adapting according to who joins in the ecosystem.

R-Urban in practice

The positive socio-ecological impact of R-Urban in this case study is the direct result of a commoning circular economy based on community-run ecological systems. The hubs and their components provided an appropriate infrastructure for an effective framework for governance, enabling the various ecological and economic loops formed to work together coherently for the benefit of the local community ().

Table 2 R-Urban hubs impact, 2015

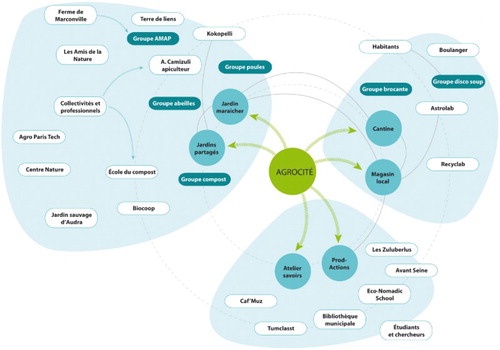

One of the main ecological and economic systems generated by the Agrocité garden involved locally produced vegetables and animal products (eggs, honey, worm compost). These were distributed locally through the mini market, the canteen and the shop. The Agrocité canteen provided a hybrid economic model, where a group of unemployed inhabitants from the area (men and women) took turns to prepare canteen meals once a week, cooking dishes with vegetables from the garden and donating 20% of the profit to cover part of Agrocité’s expenses.

Also, the School of Compost (which ran periodically at Agrocité) implemented an external training programme. This paid for Agrocité’s maintenance expenses through a small rent to the hub.Footnote3

Another important system concerned organic waste: peelings from the canteen, waste from the neighbouring markets and local shops (Biocoop shop La Bruyere), beer malt from local breweries (Astrolab), as well as organic domestic waste from the neighbourhood were collected. These were turned into compost for the garden and also used for heating and seedlings, the latter being produced in collaboration with the municipal environment department. These systems are not only material but also include services such as those offered by workshops (knitting, crocheting, cooking, aromatherapy) involving unemployed women living in the neighbouring tower blocks of Colombes, the Community Supporter Agriculture (CSA) scheme involving a farmer from the region, the beekeeping course and the School of Compost training course for compost masters to enable them to be employed by the municipality.

The non-consumerist shop sold products from the garden and the canteen but also from other local producers (honey and bee products, local beer, syrups and jams). The systems were linked to specific spaces (storage areas, processing and distribution spaces) and generated collective and coordinated activity timeframes ().

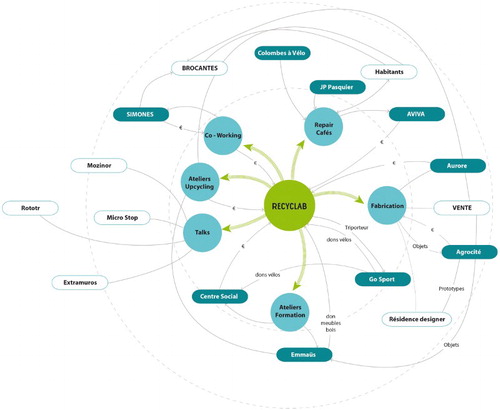

The recycling system in the Recyclab hub operated through the collection of materials (wood, metal textiles) from various local sources including joinery from demolition, scrap from carpenters’ workshops and wood packaging. This system generated a variety of social and economic relationships including: working with a sport retail chain that recycled old bicycles sent to Recyclab to be turned into cargo bikes by being partially self-built by the users; a local college (Lycée Valmy) providing textile waste to be used by designers in residence at Recyclab; and furniture recovery via a local group of manufacturers using the co-working space at Recyclab. In addition, local volunteers, including a retired professional engineer, regularly shared their know-how at the Repair Cafes ().

At Agrocité, concentric actor-networks were formed around different groups and initiatives to manage the various ecological systems: the market garden, chickens, bees, compost, flea markets, disco-soup events, prod-actions and the canteen. This network-based micro-management of ecosystems weaved together the economic, the social and the ecological. Each system acts at the same time as a process and a commons and all activities participate in the overall commoning process: ‘We are here to share: to share time, knowledge, products, meals, music,’ according to one local inhabitant.Footnote4 Specific goods and services also generated specific networks in a similar way at Recyclab through co-working programmes, repair cafés, up-cycling workshops, manufacturing and training workshops (–).

Local partnerships were formed in parallel with the gradual development of the user and stakeholder networks. These involved numerous organizations and local institutions to develop activities in relation to R-Urban including the Régie de Quartier, the Cultural and Social Centre Fossés-Jean, the Social Centre Europe, Lycee Valmy, the Biocoop La Bruyere and the Aurore organization. The overall network started to construct a resilient environment across the neighbourhood. At the same time, the network constructed greater social trust and proactive civic dynamics, which are very important assets in times of crisis and uncertainty (Platts-Fowler & Robinson, Citation2013). This has been evidenced by the quality of the relations between members, that started to collaborate in order to accomplish collective tasks, the growing number of initiatives and partners in the network, and the transformation within different individual subjects (from isolated unemployed to socially active and eventually self-employed in a collective business).

One result of R-Urban in practice is that it has become a reference for municipalities, professionals and project leaders. New urban resilience hubs are planned for the Parisian region (R-Urban Gennevilliers, R-Urban Bagneux and R-Urban Montreuil). R-Urban is now setting up a wider Development Trust to operate across local and regional scales, which will take the form of a Cooperative Society of Collective Interest (SCIC), working with a network of like-minded partners including AgroParisTech, CHP, Habitat Solidaire, La NEF, Le Labo ESS, L’Atelier ESS and Terre de Liens. The SCIC will offer a mutual coordination platform for all hubs and provide a mechanism for developing governance and solidarity.

As a result of the practical demonstration of R-Urban, various researchers, artists, activists, interns and visitors became interested in adopting the R-Urban strategy in other contexts. In order to disseminate and develop the R-Urban strategy in these other contexts, a number of clear principles and protocols were set up by aaa to integrate and support this wider network of commons. An R-Urban Charter was developed to help create opportunities for new initiatives and new hubs to emerge in other neighbourhoods, other cities and other countries (http://r-urban.net/en/charter/).

Governance challenges

Despite the various successful outcomes of the R-Urban strategy in practice, the co-production process within R-Urban nevertheless faced numerous internal and external challenges. If the framing of a project does not deal directly with the idea of resilient response related to life-threatening conditions, then it is more difficult to maintain a focus because the imperative of resilience is not of immediate concern. This raises the question of how to promote a resilience agenda with citizens who are not particularly ecologically literate or socially active, and have other more immediate priorities related to work, health and housing. Some citizens in Colombes were unaware of the resilience imperative because they lacked any connection or involvement with the place in which they lived. Education for resilience was needed in this context, and R-Urban was meant to allow a gradual familiarization with resilience issues through mutual learning and community of practice (Wenger, Citation1998).

Involvement and understanding

The large majority of local citizens who did not join the R-Urban community did not necessarily understand the idea of self-management, collective social organization, the economic and ecological benefits or the modest architecture and the deliberately improvised aesthetics of the hubs (i.e ., the integration of reused and recycled materials). The R-Urban way of working needs time to allow capacities to develop in citizens and diffuse through the community. The development of the practices such as urban agriculture may well be new to urban citizens.

The R-Urban project placed particular emphasis on making visible the direct benefits of improved social relations, health conditions and peer learning processes. In reality, it proved difficult to maintain the long-term involvement of people who lived and worked in precarious conditions. People attended the activities according to their availability depending on their work and family commitments. Interestingly, those who were able to attend R-Urban activities together with their family proved to be the most stable and regular participants.

Cohesion and conflict

Like many collective projects, R-Urban generated both cohesion and conflict (Coy & Woehrle, Citation2000). Most internal conflicts occurred between users with different visions about the collective management of the project or who attempted to appropriate tools and opportunities for their own personal purposes. The management of such interpersonal conflicts was always led by a group of users and stakeholders in dialogue with the protagonists. Conflict resolution skills were key in selecting the leaders of the two hubs. These leaders were confirmed democratically by the users’ organizations to coordinate the management of the hubs. In an ‘agonistic’ project such as R-Urban, which has no predetermined agenda, the conflicts, with only few exceptions, were not particularly subversive and disruptive but, in fact, more activating and transforming of the project itself. As Chantal Mouffe points out, agonism is the keystone of radical democracy (Mouffe, Citation2005). An ‘agonistic space’, according to Mouffe, allows the possibility of a conflict of interests and values, and the expression of different alternatives, which are arguably a prerequisite for truly collaborative resilience.

Institutional support

In terms of external challenges for R-Urban in Colombes, there was a distinct lack of institutional support structure in place (for this type of project). New and exceptional agreements had to be negotiated with various authorities. Setting up the system of plant filtering for the grey water and the installation of the compost toilets, required derogations from the city services because the off-grid sewage system in this urban area was not legal. This involved a negotiation for the non-payment of the grey water treatment provided by the city services as it was not used by the R-Urban hubs. The only regulation in place that truly supported R-Urban civic resilience practice related to local energy production, which enabled this energy to be sold to the national grid at a good price. The small surplus from this price fixing was then returned back into the R-Urban hubs to cover maintenance costs.

Access to space

Access to space for temporary use by the hubs proved to be a major challenge. The speculation pressure on land is enormous in dense cities (Harvey, Citation2008). Access to space was a political issue for a municipality which supported speculative development in Colombes.

The leases obtained for the two R-Urban hub sites were only short-term (of one year duration). The municipal administration was not confident enough to provide medium- or long-term leases for such an experimental project, which extended beyond their term of office. They wanted to have the possibility to develop the land further. From their perspective, R-Urban was considered to be only a temporary project.

The role of power in resilience strategies

A key difficulty in the implementation of the R-Urban strategy was the complexity of the power relations with the municipal administration. In particular, there was resistance by the municipal services in Colombes to adopt fully the protocols established within the co-produced management of the project. According to the funding contract, the municipality was supposed to act as a partner and facilitator of the implementation of the strategy and not as a client or authority.

The process of transitioning requires a partner-state, which supports and facilitates citizen initiatives rather than managing in the usual top-down fashion (Bawens, Citation2015). It proved extremely difficult to transform the normative relations with elected officials and municipal services, and to change their understanding and habits to act as facilitators rather than managers. This hierarchical governance model, the fear of decision-taking within new processes, the lack of capacities and ecological literacy combined with a resulting passivity and indifference, were the key reasons why most administrators and elected officials in Colombes did not play an active role in a project in which the municipality was meant to be an official partner.

The tensions described above culminated in a situation of conflict generated by the change in the municipal administration following local elections in May 2014. The new administration decided to abolish and demolish the R-Urban hubs.Footnote5 This situation raises serious questions about the limitation of current political regimes to be able to address and accommodate civic resilience (Shearman & Smith, Citation2007; Scharmer, Citation2010) – particularly over the medium-term. The absence of local government support raises the question of whether civic organizations have sufficient capacity to co-produce resilience via commoning practices at the neighbourhood level.

Legislation to protect commons

Currently, there is a lack of specific legislation to protect the commons in Europe (Capra & Mattei, Citation2015). No political definition and legislation exists to protect what could be called a ‘right to resilience’ through commoning (Petcou & Petrescu, Citation2015). In the absence of such legislation, there is a need for the state to ‘assist, enable and support’ (Weston & Bollier, Citation2013, p. 199) the institutionalization of commoning for resilience approaches and to sustain the human rights that are part of this process.

Without political definition and protecting legislation, the commons depend on the good will of local governments or other external administrations. However, these organizations can refuse to recognize the legitimacy of self-organization (Gutwirth & Stengers, Citation2016). With some irony, the new administration in Colombes decided to demonstrate its interest in ‘resilience’ with plans to build a 4000 m2 privately owned vertical farm in Colombes (Arc Sportif Masterplan, June 2016), while at the same time aiming to demolish an existing farm held in common (Agrocité). This presents a new form of ‘enclosure’ (Linebaugh, Citation2009), as in other cases of privatization of community-controlled resources already well under way elsewhere (Alden Wily, Citation2015; Bollier & Helfrich, Citation2012; Padilla, Citation2015).

The local decision to dismantle R-Urban triggered a wave of solidarity amongst professionals, researchers, citizens and residents of Colombes who have engaged in different forms of protest. This is a new stage within the R-Urban co-production process which is now framed as an advocacy campaign and political struggle. It aims to defend the socio-ecological commons created, to challenge the local government adversity and claim recognition of the success of the project.

Colombes inhabitants have engaged at a political level. As an 80-year-old member of the canteen and gardeners group stated:

This is a project which is very good for us. One should not touch it. To think it could disappear is a scandal. Yes, I said the word, and those around me said: you’re right!’.Footnote6

However, R-Urban is not alone in its struggle for social and environmental justice as other communities have also failed (Pulido, Kohl, & Cotton, Citation2016).

Conclusions: transcending the limits of resilience co-production

The R-Urban hubs and processes endeavoured to demonstrate what citizens can achieve if they engage in different ways in co-producing resilience and transforming themselves from users to stakeholders and from relatively passive inhabitants to initiators of collective resilience practices and economies. R-Urban showed that architects and researchers could play an important role in designing and creating new conditions for resilient living through communing. The project also underlines the challenges of such an approach in terms of conflicts and political blockages, the general lack of supportive regulations and the lack of civic skills and expertise for such project development. New local regulations should be negotiated and implemented for the needs and advancements of such projects. Provision for community-run spaces to develop resilience practices should be provided through regulations in neighbourhood planning.

R-Urban demonstrates the relevance of a political–ecological approach to resilience through co-production and collective governance. It further demonstrates how this process can be made visible and physical through a network of self-managed hubs. Such a approach enhances the control by the community over the metabolic system of the neighbourhood. It specifically addresses ecology in political terms ‘not only preserving the commons but also struggling over the conditions of producing them’ (Negri & Hardt, Citation2009, p. 171) as a form of commons-based resilience.

Although it appears that governments may support the idea of ‘community resilience’, this can easily change. Community resilience can be perceived as a threat to governments by empowering communities to promote a post-capitalist agenda (Cretney & Bond, Citation2014; Scharmer, Citation2010). This is why civic initiatives at the neighbourhood and city level are particularly vulnerable to mainstream politics. However, it is at this level that the processes of co-production can potentially provide new forms of social and ecological self-governance and offer solutions for securing resilient transformation. Local governments must understand their evolving role as partners and facilitators rather than as managers in such processes.

Although the R-Urban experiment was blocked by politicians, it would be a mistake to consider it as a failure. The positive results and the extensive interest it has raised demonstrate its potential impact at several levels: society, the professions and the policy-makers. This attempt to produce a commons-based resilience can be understood as a ‘generative institution’ (Capra & Mattei, Citation2015). This can challenge existing public institutions to recognize communities ‘responsibility with power’ to prompt change at different levels and identify policy and procedural gaps.

R-Urban has demonstrated through its ecological, economic and social results that resilience can be co-produced at the neighbourhood level. What was perhaps underestimated was the importance of its political agency. A commons-based resilience project is a political project too and skills for negotiation with mainstream political institutions are needed. These negotiations should be considered as integral part of the co-production process.

Recommendations for future research arising from the R-Urban experience are as follows:

the development of new legislation to protect commons-based resilience and to provide access to legal support for organizations working in the area of civic resilience at the neighbourhood and city level

the promotion of civic alliances with citizens at national and trans-national levels, providing shared knowledge, academic inputs and proactive support through policy developments on co-produced resilience

co-production of town and neighbourhood planning to include provision of access to space for experimental projects of civic resilience

training to increase ecological literacy within the public and civic sector to enable co-produced resilience within neighbourhoods and cities

funding and support to advance practice-based research and produce new performative knowledge in this area

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous time and energy given by the wider research team, design team and residents involved in R-Urban.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCiD

Doina Petrescu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3794-3219

Notes

1 Transition Town Network was founded in 2006 by Rob Hopkins in Totnes, UK, and has now become global. It focuses on connecting grassroots initiatives to increase self-sufficiency to reduce the potential effects of peak oil, climate destruction and economic instability (https://transitionnetwork.org/; Hopkins, Citation2011).

2 r-urban.net; urbantactics.org.

3 Participants in the training programme also used the canteen during the programme, aiming for a local economy that mixed reciprocal exchange (hardware and know-how), contribution to the commons and also provided personal benefits.

4 Parole d’Habitants (https://vimeo.com/156241755).

5 One year after the inauguration and successful implementation of the two R-Urban hubs, the new municipality decided to prevent their continuation for political reasons. The newly elected Mayor of Colombes positioned herself against the previous mayor who supported the implementation of the project in Colombes by publicly stating that her political agenda was divergent from the R-Urban agenda. In a radio interview at the time, the new chief executive of the municipal government stated that ‘We have no moral obligation in relation to this organisation (aaa and R-Urban) because it was not our choice’ (Radio Classique, broadcast 18 September 2015). In June 2015, the new mayor decided to replace the Agrocité hub with temporary private car park for 80 cars. At the same time, without any reason given, the municipality refused the renewal of the temporary lease for Recyclab and subsequently asked for its removal. Immediately after this decision was announced, a request for demolition of the two R-Urban hubs was processed through a litigation procedure at the Tribunal Administratif. The case went in favour of the municipality concerning Agrocité. However, the request for the Recyclab removal was rejected. Although R-Urban contested the judgement about Agrocité at the Court de Cassation, Agrocité is currently under threat of demolition and eviction by force. The mayor mentioned at one of the sessions of the City Council the presence of another urban regeneration project conducted in a neighbouring area by the Agence Nationale de Renouvelement Urbain (ANRU – The National Office for Urban Renewal) within a top-down regeneration scheme, as one of the main reason to remove the R-Urban hub. This happened despite R-Urban being internationally recognized for pioneering citizen-led urban regeneration, as confirmed by the numerous international prizes awarded to the project.

6 See note 4.

References

- Alden Wily, L. (2015). The global land grab: The new enclosures. In D. Bollier & S. Helfrich (Eds.), o.c., resp. p. 132–140 et p. 157–160.

- AnArchitektur. (2010). On the commons: A public interview with Massimo De Angelis and Stavros Stavrides. E-flux, 17. Retrieved July 10, 2016, from http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/150.

- Andrews, D. (2015). The circular economy, design thinking and education for sustainability, Local Economy, 30(3), 305–315. doi: 10.1177/0269094215578226

- Barnes, P. (2014). The political economy of localization in the transition movement. Community Development Journal. doi:c10.1093/cdj/bsu042

- Bawens, M. (2015). Sauver le monde: vers une économie post-capitaliste avec le peer-to-peer. Paris: Les liens qui libèrent.

- Beilin, R., & Wilkinson, C. (2015). Introduction: Governing for urban resilience. Urban Studies, 52(7), 1205–1217. doi: 10.1177/0042098015574955

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E.L., BurnSilver, S., Cundill, G., Dakos, V., … West, P.C. (2012). Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. The Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37, 421–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-051211-123836

- Blokland, T., & Savage, M. (Eds.). (2008). Networked urbanism: Social capital in the city. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Bollier, D. (2014). Think like a commoner: A short introduction to the life of the commons. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

- Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (Eds.). (2012). The wealth of the commons. A world beyond market and state. Amherst: The commons strategies group/Levellers Press.

- Borne, E. (2012). Atelier d’architecture autogérée: sous les pavés, la résilience urbaine, Le courrier de l’architecte. Retrieved June 12, 2016, from http://www.lecourrierdelarchitecte.com/article_3626

- Botkin, D. B. (1990). Discordant harmonies: A new ecology for the twenty-first century. New York: Oxford University.

- Boyd, E., & Juhola, S. (2014). Adaptive climate change governance for urban resilience. Urban Studies, 52(7), 1234–1264. doi: 10.1177/0042098014527483

- Boyle, D., & Harris, M. (2009). The challenge of co-production: How equal partnerships between professionals and the public are crucial to improving public services. London: Nesta.

- Braungart, M., & McDonough, W. (2002). Cradle to cradle: Remaking the way we make things. New York: North Point Press.

- Brock, K., & McGee, R. (Eds.). (2002). Knowing poverty: Critical reflections on participatory research and policy. London: Earthscan Publications.

- Brown, G., Kraftl, P., & Pickerill, J. (2012). Holding the future together: Towards a theorisation of the spaces and times of transition. Environment and Planning A, 44(7), 1607–1623. doi: 10.1068/a44608

- Cahn, E. S. (2000). No more throw-away people: The co-production imperative. Washington, DC: Essential Books.

- Cameron, D. (2011). PM’s speech on Big Society, 14 February. Retrieved from http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/speeches-and-transcripts/2011/02/pmsspeech-on-big-society-60563

- Capra, F., & Mattei, U. (2015). The ecology of law: Toward a legal system in tune with nature and community. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Castán-Broto, V., & Allen, A. (2011). Interdisciplinary perspectives on urban metabolism. A review of literature, Project Proposer and Co-Applicants. London: UCL.

- Connors, P., & McDonald, P. (2011). Transitioning communities: Community, participation and the Transition Town movement. Community Development Journal, 46(4), 558–572. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsq014

- Coy, P.G., & Woehrle, L.M. (2000). Social conflicts and collective identities. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cretney, R. (2014). Resilience for whom? Emerging critical geographies of socio-ecological resilience. Geography Compass, 8(9), 627–640. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12154

- Cretney, R., & Bond, S. (2014). ‘Bouncing back’ to capitalism? Grass-roots autonomous activism in shaping discourses of resilience and transformation following disaster. Resilience, 2(1), 18–31. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2013.872449

- De Angelis, M. (2007). The beginning of history: Value struggles and global capital. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Diprose, K. (2015). Resilience is futile: The cultivation of resilience is not an answer to austerity and poverty. Soundings, 58, 44–56. doi: 10.3898/136266215814379736

- Douthwaite, R. (1996). Short circuit: Practical New approaches to building more self-reliant communities. Dartington: Green Books.

- Feola, G., & Nunes, R. (2014). Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the transition movement. Global Environmental Change, 24, 232–250. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.011

- Ferrao, P., & Fernandez, J. (2013). Sustainable urban metabolism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B. H., Scheffer, M. Chapin III, F. S., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4): 20. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum.

- Geddes, P. (1915). City in evolution. London: Williams & Norgate.

- Gibson-Graham, K. J., Cameron, J., & Healy, S. (2013). Take back the economy: An ethical guide for transforming our communities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Godschalk, D. (2003). Urban hazard mitigation: Creating resilient cities. Natural Hazards Review, 4(3), 136–143. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2003)

- Goldstein, B. E. (Ed.). (2012). Collaborative resilience: Moving through crisis to opportunity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Government, H. (2010). Decentralisation and the localism bill: An essential guide. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Gunderson, L. (2000). Ecological resilience—In theory and application. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 31, 425–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.425

- Gutwirth, S., & Stengers, I. (2016). Le droit à l’épreuve de la résurgence des commons in Revue juridique de l’environnement (rje) 2016/1.

- Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53(9–10), 23–40.

- Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen contradictions and the end of capitalism. London: Profile Books.

- Hirst, P. (1993). Associative democracy: New forms of economic and social governance. London: Polity.

- Holden, M., Li, C., & Molina, A. (2015). The emergence and spread of ecourban neighbourhoods around the world. Sustainability, 7(9), 11418–11437. doi: 10.3390/su70911418

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Holling, C. S. (1982). Myths of ecology and energy. In L. C. Ruedisili & M. W. Firebaugh (Eds.), Perspectives on energy: Issues, ideas, and environmental dilemmas (3rd ed., pp. 8–15). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Holloway, J. (2010). Crack capitalism. London: Pluto Press.

- Hopkins, R. (2008). The transition handbook: From Oil dependency to local resilience. Totnes: Green Books.

- Hopkins, R. (2010). What can communities do. Retrieved February 14, 2013, from http://www.postcarbon.org/Reader/PCReader-Hopkins-Communities.pdf

- Hopkins, R. (2011). The transition companion: Making your community more resilient in uncertain times. Totnes: Green Books.

- Hornborg, A. (2009). Zero-Sum world: Challenges in conceptualizing environmental load displacement and ecologically unequal exchange in the world-system. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 50(3–4), 237–262. doi: 10.1177/0020715209105141

- Howard, E. (2013 [1889]). Garden cities of to-morrow. London: Routledge.

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Joseph, J. (2013). Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. Resilience, 1(1), 38–52. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2013.765741

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, M., & Conaty, P. (2012). The resilience imperative: Cooperative transitions to a steady-state economy. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

- Linebaugh, P. (2009). The Magna Carta manifesto – liberties and commons for all. Oakland: University of California Press.

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. doi: 10.1177/0309132512454775

- Maguire, B., & Cartwright, S. (2008). Assessing a community’s capacity to manage change: A resilience approach to social assessment. Retrieved from http://adl.brs.gov.au/brsShop/data/dewha_resilience_sa_report_final_4.pdf

- Mapes, J., & Wolch, J. (2011, February). ‘Living Green’: The promise and pitfalls of new sustainable communities. Journal of Urban Design, 16(1), 105–126. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2011.521012

- Mason, K., & Whitehead, M. (2012). Transition urbanism and the contested politics of ethical place making. Antipode, 44(2), 493–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00868.x

- McKinsey and Company (2012). Circular economy report Vol. 1 – 2012. Retrieved accessed May, 7, 2016 from www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/business/reports

- Mouffe, C. (2005). On the political (Thinking in action). New York: Routledge.

- Negri, A., & Hardt, M. (2009). Commonwealth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nelson, S. H. (2014). Resilience and the neoliberal counter-revolution: From ecologies of control to production of the common. Resilience, 2(1), 1–17. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2014.872456

- Nevens, F., et al. (2012). Urban transition labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 50(Special Issue: Advancing sustainable urban transformation), 111–122.

- Office, C. (2011). Strategic national framework on community resilience. London: UK Government.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Padilla, C. (2015). Mining as a threat to the commons: The case of South America. In D. Bollier & S. Helfrich.

- Peck, J., & Tickell, A. (2002). Neoliberalizing space. Antipode, 34(3), 380–404. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00247

- Petcou, C., & Petrescu, D. (2015). R-URBAN or how to co-produce a resilient city. Ephemera, 15(1), 249–262.

- Platts-Fowler, D., & Robinson, D. (2013). Neighbourhood resilience in Sheffield: Getting by in hard times. Sheffield: CRESR/Sheffield City Council.

- Pohl, C., Rist, S., Zimmermann, A., Fry, P., Gurung, G. S., Schneider, F., … Wiesmann, U. (2010). Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: Experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Science and Public Policy, 37(4), 267–281. doi: 10.3152/030234210X496628

- Polk, M. (Ed.). (2015). Co-producing knowledge for sustainable cities: Joining forces for change. London: Routledge.

- Pulido, L., Kohl, E., & Cotton, N.-M. (2016). State regulation and environmental justice: The need for strategy reassessment. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(2), 12–31. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2016.1146782

- Radywyl, N., & Biggs, C. (2013). Reclaiming the commons for urban transformation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 50, 159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.020

- Rapoport, E. (2011). Interdisciplinary perspectives on urban metabolism. A review of literature. UCL Environmental Institute paper. London: UCL.

- Robards, M. D., Schoon, M. L., Meek, C. L., & Engle, N. L. (2011). The importance of social drivers in the resilient provision of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.12.004

- Robbins, P. (2004). Political ecology: A critical introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Rohe, W. M. (2009). From local to global: One hundred years of neighborhood planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75(2), 209–230. doi: 10.1080/01944360902751077

- R-Urban. (2014). R-Urban. Pratiques et reseaux de resilience urbaine. Retrieved from http://rurban.net

- Scharmer, C. O. (2010). Seven acupuncture points for shifting capitalism to create a regenerative ecosyste economy. Oxford Leadership Journal, 1(3), 1–21.

- Scoones, I. (1999). New ecology and the social sciences: What prospects for a fruitful engagement? Annual Review of Anthropology, 28, 479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.479

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shaikh, A., & Kauppi, C. (2010). Deconstructing resilience: Myriad conceptualizations and interpretations. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 3(15), 155–76.

- Sharifi, A. (2016). From garden city to eco-urbanism: The quest for sustainable neighborhood development. Sustainable Cities and Society, 20, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2015.09.002

- Shearman, D., & Smith, J. W. (2007). Challenge and the failure of democracy. Westport: Praeger.

- Stavrides, S. (2016). Common space: The city as commons. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tibbs, H. B. C. (1992). Industrial ecology – an agenda for environmental management. Pollution Prevention Review, Spring 1992, 167–180.

- Timmerman, P. (1981). Vulnerability. Resilience and the collapse of society: A review of models and possible climatic applications. Environmental Monograph No. 1, Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Toronto.

- Trogal, K., & Petrescu, D. (2015). Architecture and resilience: Strategies to deal with global change at a human scale. Introduction to Architecture and Resilience at a Human Scale conference proceedings, 10–12 September, Sheffield.

- United Nations. (2012). Resilient people, resilient planet: A future worth choosing. New York: United Nations (United Nations Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Global Sustainability).

- Vale, L. J. (2014). The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Building Research & Information, 42(2), 191–201. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2014.850602

- Vigar, G., & Healey, P. (2002). Developing environmentally respectful policy programmes: five key principles. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 45(4), 517–532. doi: 10.1080/09640560220143530

- Wagenaar, H., & Wilkinson, C. (2013). Enacting resilience: A performative account of governing for urban resilience. Urban Studies. doi:10.1177/0042098013505655

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5.

- Welsh, M. (2014). Resilience and responsibility: Governing uncertainty in a complex world. The Geographical Journal, 180(1), 15–26. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12012

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Werner, E. (1995). Resilience in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(3), 81–85. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772327

- Weston, B. H., & Bollier, D. (2013). Green governance. Ecological survival, human rights and the law of the commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkinson, C. (2012). Social-ecological resilience: Insights and issues for planning theory. Planning Theory, 11(2), 148–169. doi: 10.1177/1473095211426274

- Wong, C.Y., Wong, C.W.Y., and Boonitt, S. (2015). Integrating environmental management into supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(1/2), 43–68. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0110

- Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Zimmerer, K. (1994). Human geography and the “New ecology”: The prospect and promise of integration. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 84, 108–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1994.tb01731.x