ABSTRACT

Addressing work environment design methods has become increasingly important due to pandemic-induced changes in the ways and locations of work. This research addresses work environment design through a theory-informed workplace design framework to study the co-design process, the impact of spatial atmosphere on workplace experience and satisfaction, and infrequently studied spaces, i.e. meeting rooms and breakout areas. This case study is based on co-design methods, a workplace design intervention study and its evaluation. Comprehensive design is addressed through analytical dimensions of design, i.e. instrumental, symbolic, aesthetic and perceived dimensions of atmosphere and affordances. Furthermore, the spatial experience is explored through need-supply fit theory and workplace satisfaction. The pre-design results showed that employees have distinct design preferences based on perceived and analytical dimensions for technical, hybrid and creative meetings and individual work and recovery events. The workspace interventions were designed using the design information gathered from the co-design process; the changes implemented in intervention spaces increased employee satisfaction towards them. The study’s methodology contributes to establishing a theory-informed workplace design framework supporting user-centred workplace design and evaluation and indicates a role for spatial atmosphere in need-supply fit formation.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic strategically shifted the role of offices due to increased hybrid and multilocational work during and after the pandemic. Offices are still preferred by many for formal and informal work meetings, socializing and training activities although some employees prefer working from home for both individual and collaborative tasks (Appel-Meulenbroek et al., Citation2022; Bosch-Sijtsema et al., Citation2010; Halford, Citation2005; E. Yang et al., Citation2021). Employees in today's organizational culture often have the choice to work where it suits them best (Wohlers & Hertel, Citation2017), and recent studies have shown that remote and hybrid work allows flexibility with a positive impact on employees. However, full-time remote work may impact employee well-being through weakened work-life boundaries, increased technical work demands and intensified psychological and emotional work demands (Chan et al., Citation2023). The long-term impact of asynchronous communication and remote meetings on organizational culture and innovative sustainability is unknown (Chafi et al., Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022). It is, therefore, important to understand which factors in the physical work environment support working in the office and attract employee presence.

Work environment research considers the compatibility between employees and their surroundings through workplace satisfaction and environmental fit. Workplace satisfaction, by definition, is supported when the work environment is aligned with employees’ activities and personal needs (van der Voordt, Citation2004; Vischer, Citation2007; Wohlers & Hertel, Citation2017). Post-occupancy evaluation methods consider how the environment and its elements support satisfaction towards physical, spatial and organizational factors (Candido et al., Citation2016; Maarleveld et al., Citation2009).

The extent to which the physical work environment meets employees’ needs is a key determinant of employee satisfaction with their work environment (van der Voordt, Citation2004). The outcome is a combination of personal characteristics, activity patterns, needs and preferences, which influence the formation of satisfaction towards the physical dimensions of the workplace (Budie et al., Citation2019; Rothe et al., Citation2011). Workplace satisfaction, which has been shown to correlate significantly with perceived productivity and performance, is linked to employee well-being and perceived health (Bodin Danielsson & Bodin, Citation2008; Budie et al., Citation2019; Candido et al., Citation2021; Groen et al., Citation2019); design strategies should, therefore, strive to achieve environmental compatibility. Change processes, including co-design processes and preceding relocation, have an important impact towards satisfaction formation, especially in the context of new work environments (Sirola et al., Citation2022). Recent reviews of workplace design approaches have highlighted the importance of understanding how health and well-being support workplace characteristics and their design strategies (Bergefurt et al., Citation2022; Colenberg & Jylhä, Citation2022; Forooraghi et al., Citation2020).

The proactive approach to increasing workplace satisfaction requires understanding how different design decisions impact employees. Researchers and designers need to elucidate which combinations of spatial elements and design solutions support positive experiences to understand this. The quantitative methodological approaches that measure workplace satisfaction (Candido et al., Citation2016; De Been & Beijer, Citation2014; Haynes, Citation2008) favour research settings that study measurable factors in the work environment, such as office layout, privacy, distraction or interaction-affording factors. The quantitative research approach and its limitations may lead to the dichotomy of studying private versus open spaces. At the same time, there is only a little research on separate spaces in the work environment, such as meeting rooms, concentration-supporting spaces and recovery spaces (Brunia et al., Citation2016; Gjerland et al., Citation2019; Haynes, Citation2008).

Employee reactions towards interior aspects of the work environment are challenging to measure quantifiably, and the methods used to understand these phenomena are explorative and qualitative (Brunia et al., Citation2016; Sander et al., Citation2019). Workplace aesthetics, which is linked to affective experiences and is indicated as influencing employee behaviour (Barton & Le, Citation2023; Sander et al., Citation2019), has remained an under-researched topic compared to objectively and subjectively measurable interior elements: for example, ambient factors, such as lighting, acoustics or thermal comfort; and architectural features, such as layout or spatial privacy (Bergefurt et al., Citation2022). Access to daylight, scenery and plants has shown positive effects on employees, thus biophilic design has generated more attention than general interior design (Beute & de Kort, Citation2014; Kellert & Wilson, Citation1993; Zhong et al., Citation2022). However, understanding affective workplace experiences is important because employees do not experience their environment neutrally (McCoy & Evans, Citation2005; Sander et al., Citation2019).

The need-supply fit theory, the sub-theory of person-environment fit (Edwards et al., Citation1998; Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005), provides a theoretical model to explore workplace alignment and satisfaction formation. Both personal and environmental variables influence fit formation, positively impacting workplace satisfaction when employee needs are considered through functional, psychological and physical viewpoints (Budie et al., Citation2019). The mismatches between spatial and behavioural dimensions negatively affect satisfaction and perceived productivity (Candido et al., Citation2021). The research applying the need-supply fit model has taken two approaches: through a general fit, such as Gerdenitsch et al. (Citation2018), or a more focused approach, for example, in studies applying models with a combination of factors such as activity, task complexity and personal need for privacy (Hoendervanger et al., Citation2019) or IEQ factors (Radun & Hongisto, Citation2023). The fit approach can be linked to workplace design research because current models test attributes that are directly linked to workplace design solutions.

A limited amount of research exists concerning workplace design processes, co-design methods or how design knowledge is incorporated into workplace design (Rolfö et al., Citation2017); this is a recognized knowledge gap (Brunia et al., Citation2016; Colenberg et al., Citation2021; Gjerland et al., Citation2019). Prior studies have noted the positive impact of co-design processes on employee empowerment (Vischer, Citation2007), but the impact may be adverse if employees perceive them as pseudo-participation (Søiland, Citation2021).

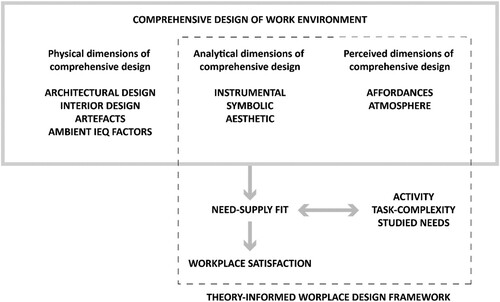

This study tests a theory-informed workplace design framework through a co-design process. The framework includes need-supply fit and workplace satisfaction as theoretical models for workplace experience. It connects the workplace experience to the comprehensive design through the perceived dimensions of atmosphere and affordances. The perceived dimensions and workplace experience are connected to the design process through an analytical model of instrumental, symbolic and aesthetic design dimensions.

Furthermore, this research aims to study whether the need for atmosphere can be used as a design attribute in the need-supply fit formation through which the design information attributes can be collected in a co-design process and those attributes identified that need to be implemented into the intervention design to support workplace satisfaction formation. This study also contributes to understanding infrequently studied spaces in offices, meeting rooms and breakout areas.

Constructing a theory-informed framework for workplace design and research through co-design

This study considers workplace experience from the design perspective and the attributes of spatial support through co-designing spaces for different work activities. To extend the spatial understanding of spatial support, the work environment design is considered here through both the perceived attributes of atmosphere and affordances and the analytical design dimensions: instrumental, symbolic and aesthetic. These dimensions help in understanding how the combination of spatial attributes and artefacts contributes to the experience of design outcome and workplace satisfaction.

Co-design approach to produce information

Co-design practices, which foster interdisciplinary collaboration and involve users, build on the participatory design tradition that originated from the notion that users affected by design should have a voice in the design process (Blomberg & Karasti, Citation2012). Even though co-design has the potential to support the efficiency of design processes by ensuring the compatibility of users’ needs and the design outcome (Antonini, Citation2021; Binder et al., Citation2011), they are not yet formalized research practices with a standardized model for generating new academic knowledge in many research areas (Busciantella-Ricci & Scataglini, Citation2024), including work environment research.

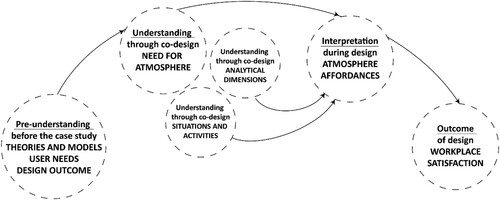

Design, as a practice, is based on pre-understanding, understanding, interpretation and reflection-in-action (Schön, Citation1983; Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996). Designers who start a new project already have a preconceived idea of the design process's end product. Available parameters guide the design objectives in the initial stages. Interpretation and understanding develop and guide the designer towards the project's explicit needs as the project proceeds (Schön, Citation1983; Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996). Co-design methods can increase understanding; workplace designers may thus benefit from frameworks that guide them in collecting design information. The potential benefits of co-design processes in the work environment context include making visible the users’ tacit understanding of their needs: not only towards the need for privacy and interaction but also towards the awareness of the situations and the related embodied experiences, which are enforced by emotion and reflection (Binder et al., Citation2011).

Theory-informed workplace design framework connects the design process and employee experience

An evidence-based design aims to provide the best available information for design processes from research (Bae et al., Citation2019). The extensive post-occupancy evaluation research concerning work environment satisfaction provides evidence-based design information that can be applied, for example, to design acoustics and lighting. The elements and artefacts that form the physical work environment are on the dimensions of architectural design, interior design, artefactual and ambient attributes when the comprehensive design is approached from a design perspective (Hoff & Öberg, Citation2015). Thus, they cannot be treated as attributes of the same scale or form. Furthermore, they form entities, and even if similar elements and artefacts are included in the design, the comprehensive work environment experiences vary. Therefore, this study approaches the comprehensive physical work environment from a design perspective, and the theory-informed framework aims to reach from the physical environment’s design towards the perceived environment that employees experience.

The theory-informed framework presented in this study () considers workplace experience from the design perspective. The designers operate on all the comprehensive design dimensions as presented in . The artefacts and attributes implemented into the design contribute to forming affordances and spatial atmospheres. These perceived dimensions of the comprehensive design need a mediating model to link to the physical environment and its attributes. Therefore, the theory-informed workplace design framework also considers the comprehensive design from an analytic viewpoint through the instrumental, symbolic and aesthetic dimensions. The need-supply fit and satisfaction form an overarching theoretical model that guides the design process to fulfil employee needs through the comprehensive design.

The analytical and perceived dimensions support framing the design process to limit the boundaries, focus decision-making and provide a way to interpret information. Experienced designers apply this process to align with the needs of the situation they are addressing (Plowright, Citation2014; Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996).

Perceived space: affordances and atmospheres

A comprehensive work environment design traditionally includes spatial organization, architectural and interior design elements, artefacts and ambient conditions (Hoff & Öberg, Citation2015). Those categorisations, however, do not express the experiential nature of the design and how the environment is perceived by its users. The perceived environment can be considered through the concepts of affordances and atmosphere: Affordances can be characterized as environmental properties of what the environment provides, furnishes or is for (Gibson, Citation1986; Norman, Citation1988), i.e. how it supports different activities. The different elements of a comprehensive design together create a spatial atmosphere, which can be understood as an emotional-sensory perspective on design and architecture. Atmosphere ties together the properties of the space and a person’s direct immersive experience within and of that space (Canepa, Citation2022). The atmosphere is integral to how surroundings are perceived as factors and artefacts integrated into the comprehensive design to generate interconnected, multisensory impressions; thus, different atmospheres are considered to emanate from the physical properties of the environment (Böhme, Citation2017; Canepa, Citation2022). Psychological research approaches spatial experience through an aesthetic dimension (Sander et al., Citation2019), which is considered to support creative thinking when experienced pleasantly and has been shown to support physical and emotional restoration: restoring, promoting and strengthening employees’ cognitive and emotional resources (Beute & de Kort, Citation2014; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004a). Conversely, undesirable aesthetic outcomes may lead to avoiding specific spaces (Babapour Chafi et al., Citation2020).

Both atmosphere and affordances are something one senses or perceives in the space. It has been suggested, theoretically, that the connection between affordances and atmospheres is that affordance-based atmospheres invite users to sense space in a certain way (Griffero, Citation2022). Norman's intake of man-made affordances (Norman, Citation1988, Citation1999) has been widely adopted by industrial designers, and the theory has been applied in affordance-based design, although the Gibsonian approach to affordances is based on ecological systems (Gibson, Citation1986; Maier, Citation2011). Additionally, some studies propose that affordances may attract or hinder actions and behaviour (Withagen et al., Citation2012, Citation2017), adding another dimension of consideration to the workplace design. The design’s affordance dimension is particularly interesting in contexts where workplace design provides multiple opportunities for choosing a workspace. Nevertheless, employees may not actively switch their spaces according to their activities, which has been shown to impact work environment satisfaction (Hoendervanger et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, it has been proposed that an informal atmosphere affords social connections (Colenberg, Citation2023).

Understanding the comprehensive design: symbolic, aesthetic and instrumental dimensions

Design-related understanding of affective experience can be considered through the multidimensional model, which posits that each artefact’s arrangement contains instrumental, symbolic and aesthetic dimensions (Elsbach & Pratt, Citation2007; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004b; Vilnai-Yavetz et al., Citation2005). This paper uses this model as an analytical framework for comprehensive design.

The instrumental dimension of artefacts and their arrangement, which promotes goals and performance in the work environment, has been theoretically linked to affordances by providing behavioural opportunities (Chemero, Citation2003; Gibson, Citation1986; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004b, Citation2004a). A well-designed instrumental dimension of the workspace fulfils the definitions of workplace satisfaction (van der Voordt, Citation2004) and need-supply fit formation (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005). However, the other dimensions, the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions, are also an inherent part of a comprehensive design. Even the most neutral and lean workspace generates an affect, thus these dimensions require further inquiry.

The symbolic dimension elicits meanings or associations towards how the space is intended to be used (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2019; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004a), mediating what spatial design conveys to its user, for example, formality, playfulness or creativity. The aesthetic dimension includes the selection of colours, textures, forms and their arrangement (Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, Citation2004a; Sander et al., Citation2014). An aesthetically pleasing work environment has been shown to increase workplace satisfaction and employee well-being (Bodin Danielsson, Citation2015; Kirillova et al., Citation2020). Understanding this impact in more detail is important because the positive environmental effects increase cognitive flexibility, creative problem-solving, organizational commitments, helping behaviours and performance (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2019; Sander et al., Citation2019).

Method

This design research study applies a co-design methodology to produce design-related information on employee needs and preferences. It is also an intervention study to test how the design-related information can be applied to the design process and how employees perceive the implemented changes in their environment. The methodological approach to the study follows the three phases of the research-by-design process: the pre-design, design and post-design (Roggema, Citation2017).

Co-design as a research approach

Research-by-design is an approach to studying design-related challenges in real-world settings. The approaches range from reflective and analytical studies of completed design projects to generating new knowledge through the design process itself (Roggema, Citation2017; Verbeke, Citation2013).

This study applies the three phases of research-by-design as defined by Roggema – pre-design, design and post-design (Roggema, Citation2017) – through the methodology of the participatory co-design tradition (Blomberg & Karasti, Citation2012). This paper, after presenting the empirical results of each phase of the study, explores the three-phase process approach and the applied theory-informed framework through hermeneutic inspection to distinguish the pre-understanding, understanding and interpretation during the design process (Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996).

Co-design-based design research has different aims compared to quantitative research approaches. Formulating a theory-based hypothesis and its empirical testing is plausible in research settings with known variables. Design research may produce prototypes; in this study, the intervention design integrates many types of information, including theoretical. Prototypes as such present the designers’ ways to build the connection between fields of knowledge and progress towards the design outcome. The designing of prototypes produces knowledge that can be fed back into relevant disciplinary platforms to support theory building (Koskinen et al., Citation2011; Stappers, Citation2007).

Context of the study

The current investigation was conducted in a combi-office of a participating technology company that provides smart healthcare solutions. Local companies were asked if they would like to be involved in the project, and the case study office was chosen because of its typological layout, size and location. This case study was conducted within an interdisciplinary research project with the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; an ethical review of the project was thus conducted and approved by the Ethical Board of the FIOH, as required by the FIOH for all studies involving human participants. The study was initiated by the research team and was not part of the organizational change process.

Approximately 50 employees occupied the company's 600 m2 headquarters at the project’s start. The research group decided on the spaces of intervention before the pre-design phase. The first author led the data collection and intervention design processes. Researchers organized an online event to present the research project to the employees and recruit study participants. Participation in the study was voluntary, and volunteers signed a research consent form, informing participants of their rights.

The diverse workspaces consisted of private, shared and open offices with assigned workstations; the shared spaces included meeting rooms, breakout areas, production and product testing areas. The changes focused on shared meeting rooms and the breakout area; no changes were implemented at the assigned workstations. The intervention area comprised a multifunctional workspace (quick meetings and individual work), a formal meeting room (board meetings and on-site visitor meetings), an informal meeting room (team meetings, product development and brainstorming) and a breakout area (lunches, coffee breaks, weekly hybrid meetings with remote teams).

The pre-design phase was conducted in May; the post-design phase, 10 weeks after the intervention set-up, was completed in November–December. Only participants working full-time or hybrid in the office participated in the post-design phase. Study participants (n = 15) were male (53%) and female (47%), aged 28–53, whose job descriptions included administrative, product development, customer service and marketing tasks.

Pre-design phase process and methods

Pre-design phase methods were designed to collect information on daily activities and their related needs and to co-design surroundings for work and recovery-related scenarios. The theory-informed framework is applied in the pre-design phase to support the planning of the methods to collect design information that belongs to both the analytical and perceived dimensions of design.

Semi-structured interviews

The interviews with the study participants were organized online via Zoom. They were video and audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews covered the topics of (1) background and job description; (2) assessment of assigned workstation, shared workspaces and breakout area; (3) tasks and task-related needs and (4) recovery during the workday. The theory-informed design framework was used to collect information on the task- and recovery-related needs, such as the need for privacy, interaction, knowledge sharing and online applications, such as Zoom and Teams. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by categorization in the NVIVO qualitative data analysis tool. The established use of the intervention spaces was assessed from the interview data with a thematic analysis. The study participants’ typical tasks, workday recovery habits and related needs were also analysed from the interview data with a thematic analysis.

Co-design workshops

The participants were invited to the co-design workshops to co-design work and recovery scenarios in groups of 3 or 6. The workshops were organized online via Zoom. PowerPoint files were prepared for the workshop facilitator and participants. The tasks were presented in the participant versions of the PowerPoint files for participants to complete individually or together. The participants were asked to email the completed files to the facilitator after the workshop. The organizer’s version of the PowerPoint file included inspirational images, for example, for the facilitated discussions. The workshops contained the following tasks:

Individual task: Describe your favourite place and related activities and feelings. Participants filled out a questionnaire with the following questions and prompts: My favourite place is … ; In my favourite place, I do … ; Where?, When?; Together or alone?; What is the place like?; How do you feel in your favourite place?; and, What is the atmosphere like in the place?

Individual task: Describe 3–4 daily situations and related feelings at work. Participants filled out a questionnaire to describe 3–4 situations through the following questions and prompts: The time is … ; The place is … ; Together or alone?; What do I do in the situation?; and What do I feel in the situation?

Group task (three participants in group): Co-designed scenarios – Select three daily work or recovery-related situations and describe their related feelings and spatial atmosphere. Participants filled out a questionnaire to describe three situations consisting of the following questions and prompts: The situation is … .; ‘How do you feel in the situation?’, ‘What is the space like?’ and ‘What is the atmosphere like?’.

The co-design scenarios were selected from situations discussed during the second task with the guidance of the researcher facilitating the workshop: The selected scenarios focused on the situations that had the potential to be implemented into the intervention design. Therefore, the emphasis was on the typical uses of the pre-selected intervention spaces.

The spatial characteristics that were supportive of co-designed scenarios were discussed with visual examples, which included prompts of ‘What does the situation need?’, ‘What is the light like in the space?’, ‘What kinds of materials?’, ‘With or without colours?’ and ‘What is the colour palette like?’. The visual examples included images of different work environments, different natural lighting examples, material samples, and colour collages. The co-design workshops were video and audio recorded. The workshop recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis of co-designed scenarios

The co-design workshop dataset was thematically analysed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) using the NVIVO qualitative data analysis tool. The first part of the co-design scenario data was categorized under workshop prompts, and the analytical design dimensions were divided into the following categories: feelings, spatial characteristics and atmosphere. The data, which analytical dimensions, spatial characteristics and atmosphere inform, were deductively analysed next. The facilitated discussion was categorized into instrumental and aesthetic dimensions. The analysed data are intentionally kept information-rich because the interrelations of the workspace attributes are complex and interlinked.

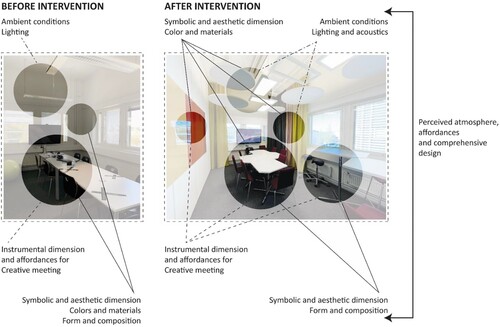

Design phase

The thematically analysed pre-design information was used to guide the design process. The design process focused on the intervention area (see , spaces A–D). The intervention, in this study’s context, refers to a temporary refurbishment of the participants’ work environment within four spaces. Each space's established purpose and use remained as such, and the design focus was targeted to improve the spaces’ atmospheric properties through symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of the theory-informed framework. The lighting and acoustic improvements were also enhanced. Supplementary Table 1 presents the detailed list of implemented changes.

Post-design phase process and methods

The post-design evaluation was conducted 10–12 weeks after implementing intervention changes within the company. This study phase included only on-site participants because some employees continued to work from home during the post-design period.

Semi-structured evaluation interviews

The participants (n = 9) were invited to on-site evaluation interviews 10 weeks after completing the intervention set-up. Two interviews occurred online via Zoom due to tightened remote work recommendations. Both on-site and online interviews were video and audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The evaluation interviews examined (1) usage of intervention spaces, (2) spatial support towards work in each intervention space, (3) recovery in the breakout area, (4) spatial support towards privacy and interaction, (5) spatial satisfaction, (6) perceived atmosphere and symbolic characteristics and (7) opinions of furniture, colours, materials, lighting and soundscape. Furthermore, the perceived symbolic characteristics between the informal and formal meeting rooms were discussed.

Evaluation workshop

The participants were invited after the evaluation interviews to online evaluation workshops 12 weeks after completing the intervention. Two workshops were organized with 4 or 5 participants in each. The evaluation workshops were video and audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The intervention spaces were separately discussed with the workshop participants in terms of (1) How spaces were used, (2) Which elements afforded the activities, (3) Which elements supported the activities, comfort and workspace satisfaction and (4) How participants perceived the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of the space.

Analysis of evaluation

The evaluation interviews and workshops were transcribed verbatim and analysed by thematic categorization (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) in the NVIVO qualitative data analysis tool. The increased or decreased workplace satisfaction experienced with the implemented intervention design was logged from individual evaluation interviews. Using a bottom-up approach and thematic content analysis, the following categories were identified and clustered from interviews and workshops. The analysed data were intentionally kept information rich to understand the workspace attribute interrelations. This paper presents the data categorized altogether under the themes Workspace satisfaction and supporting factors, Perceived atmosphere, Factors supporting the workspace comfort and satisfaction, Symbolic dimension and its perceived impact on the space and atmosphere and Aesthetic dimension and its perceived impact on space and atmosphere.

Results

The information produced in this study is presented through the pre-design, design and post-design phases (Roggema, Citation2017), followed by a reflective analysis of the theory-informed design framework and its application in this study’s design process.

Pre-design phase: task analysis and employee needs

The pre-design interviews were analysed to understand different situations: Interviewees brought up several individual work, collaboration and recovery situations. About 58% of the discussed collaborative situations were categorized as meetings: weekly company meetings, team or project meetings; design, technical development, coordination, release or retrospective evaluation meetings; client or sales team meetings; and board meetings. The participants were asked about the privacy and interaction need-supply fit attributes. The need for interaction in meeting situations was acknowledged. The need for privacy concerning meetings was brought up, which included product development, clients and board and steering group meetings – participants expressed that these discussions were considered confidential within the company. The need for knowledge sharing also varied depending on the job specifications. For example, software developers shared their knowledge through digital methods, but marketing people also used drawing boards. Most recovery situations were either lunch or coffee breaks, but nine examples of physical activity, such as walking, were brought up.

Pre-design phase: co-design workshops generated co-designed scenarios

The participants (n = 15) were next invited to co-design workshops, which comprised three tasks. The first two tasks were organized to support the participants’ orientation into a creative mindset and to support their design thinking. The participants discussed their favourite place during the first task, intended to activate design thinking. Eleven participants discussed their favourite places that were closely connected with nature: in nature, in the countryside or at the summer cottage. The participants explored in the second task their typical workday situations, which consisted of focus-oriented individual work tasks, collaborative and meeting events, and recovery situations.

The co-design task consisted of free and facilitated discussions. The free discussion was prompted with questions concerning feelings during the activity, spatial characteristics and spatial atmosphere. The facilitated discussion prompted more detailed design information to provide organisation-specific knowledge. The co-design scenarios produced design information for the spatial atmosphere and instrumental, symbolic and aesthetic dimensions, which belong to the perceived and analytical dimensions of comprehensive design within the theory-informed workplace design framework (see ). presents the results of the third workshop task. Fifteen scenarios were co-designed and combined into groups of two or three. The scenarios were grouped into hybrid, technical and creative meetings, individual work, recovery alone and recovery together. The meeting scenarios presented were noticeably different regarding emotions during the meetings and requirements and preferences for the supportive surroundings. One example is the richness of the comprehensive design: the hybrid and technical meetings were considered to require a lean design that maintains the focus on the task at hand. However, the creative meeting was perceived to be best supported in a rich environment that supports out-of-the-box thinking.

Table 1. Co-designed atmospheres and spatial design preferences.

Design phase: co-design information supported intervention design process

The co-designed scenarios were used to guide the design of the intervention area spaces: the multifunctional workspace, formal meeting room, informal meeting room and breakout area. The pre-design interview dataset was used to establish how the case study company used the intervention spaces (). The appropriate co-designed scenarios were next assigned to the intervention spaces, and the thematically categorized design information was used to formulate the design aims. presents the pre-intervention photos and layout of spaces. The aesthetics were sparse, and symbolic dimensions were minimally expressed, while all spaces afforded their designated functions. Therefore, the design aims to improve the comprehensive design through the spatial atmosphere and symbolic and aesthetic dimensions. presents the design aims. The bottom half of presents the intervention design outcome, and Supplementary Table 1 presents a detailed list of implemented changes.

Table 2. Co-design informed intervention design aims.

Post-design phase: evaluation of intervention

Nine on-site or hybrid working participants were invited to the on-site interviews to assess how they perceived the changes implemented in the intervention area on the comprehensive level and through different analytical and perceived dimensions (). The post-design phase of the research connects the design process to the user experience and addresses the formation of need-supply fit through perceived spatial satisfaction. The evaluation interviews and workshops confirmed that the ways of using the studied spaces had remained unchanged. Workplace satisfaction was perceived overall to increase after interventions in each intervention space. The exceptions were that two participants for the multifunctional workspace and one participant for the formal meeting room did not perceive an increase or decrease in satisfaction towards those spaces. The interviews and workshops inquired about the reasons for increased satisfaction. The new lighting, curtains, colours and acoustics, in addition to space-specific features, such as, for example, the shape of tables in the informal meeting room and the ability to move around in the informal meeting room, were named in all intervention spaces.

Table 3. Post-design evaluation of the intervention spaces.

Work-supporting factors were also considered, in addition to the instrumental dimension, to originate from the atmosphere, the perceived dimension of the framework, which emanated from the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of design, i.e. the framework’s analytical dimensions. For example, the informal meeting room design was inspired and guided by the co-designed creative meeting scenario. Participants considered that the new atmosphere supported informal collaboration, out-of-the-box thinking, and free discussion. The symbolic dimension was perceived to be created from versatile furniture and playfully shaped tables, which made the space seem less formal and more creative. The aesthetic dimension and its contribution to the atmosphere were attributed to colours, tactile materials and shapes. Supplementary Table 2 presents the evaluation interview and workshop results in more detail through the factors that support workspace comfort and satisfaction and how symbolic and aesthetic dimensions contribute to comprehensive design and spatial atmosphere.

Reflective analysis of the co-design process and applied theory-informed workplace design framework

The study is reflected in this section through a hermeneutic circle (Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996) by considering how understanding emerges during the study’s research study design, pre-design, design and post-design phases and how the produced information is connected to the theory-informed design framework. The parts of the framework are discussed in connection to the emerging information in this study.

The role of pre-understanding in the study set-up and the design process

Design practice can be considered from a problem-solving perspective or a hermeneutical approach. Workplace design requires understanding complex interrelations of activities, needs and surroundings; thus, applying hermeneutical analysis supports understanding workplace design practice. Snodgrass and Coyne distinguish pre-understanding, understanding and interpretation from the design process (Snodgrass & Coyne, Citation1996).

presents the hermeneutic reflection of this study and the stages of processing design-related information. The pre-understanding in this study was essential for defining the theory-informed design framework and planning the methods to increase the understanding of user needs and preferences (i.e. through the pre-design phase), which, in turn, is essential for successful design outcomes. The outcome was analysed in this study through the concept of workplace satisfaction (van der Voordt, Citation2004). Satisfaction was increased throughout the intervention area, which indicates a successful design process. The need-supply fit model mediates the connection between workplace satisfaction and comprehensive design. To build on a need-supply fit model consisting of activity, needs, surroundings,, and task complexity (Hoendervanger et al., Citation2019), the need for the atmosphere was selected as a novel attribute for considering the perceived comprehensive design’s impact. Affordance is the perceived attribute that mediates work environment support through activities; however, the essential space-specific affordances were present on the company premises to support the desired activities, so this study focused on the design of spatial atmospheres.

The atmosphere and analytical dimensions of comprehensive design, specifically the symbolic and aesthetic, were important attributes of the framework for increasing the understanding towards successful design outcomes; therefore, the study design aimed to collect detailed information on these attributes (cf. ). The first part of the scenario development produced information concerning the atmospheres and symbolic and instrumental dimensions. The second part of the scenario development increased the understanding through the instrumental and aesthetic dimensions. As such, the contents of provide information for a designer on how the space could be designed. The information concerning atmospheric characteristics alone would leave an extensive interpretation of what the needed atmosphere looks like. The information on symbolic and aesthetic dimensions guided the design process to implement the spatial atmospheres through the comprehensive design preferred by this study’s participants. The co-design process was critical for increasing the understanding of needs. It is important to note that designers’ different approaches in co-design processes produce information that leads to different outcomes.

Discussing design through the term interpretation is apt because designing a workplace is not a direct transfer of information into the design but rather an interpretation of individual needs, possibilities within available premises, available resources and the design of individual spaces that form a cohesive entity. Categorizing the information produced in co-design scenarios through the theory-informed workplace design framework made the design information visible and structured during this case study. This enhanced the design process by providing a tool that enabled considering the activity, user needs and preferences to create surroundings whose design was based on informed understanding and interpretation.

Atmosphere as an attribute in the need-supply fit equation

All participants considered increased workplace satisfaction in the informal meeting room (). The implemented design enriched the space with colours, tactile materials, forms and furniture composition in a way that was informed by the participants. The design aimed towards an inspiring, stimulating and informal atmosphere, enabling movement and standing during the meeting. shows how different artefacts and design features in the informal meeting room contribute to the different dimensions of comprehensive design. The colours and materials, for example, are part of the functional attributes, such as tables, chairs, curtains and drawing boards, which contribute to the instrumental dimension and affordances. The comparison of the photos shows that the space afforded the activity of meetings before the intervention, but the atmosphere was uninspiring and sparse. The framework links the perceived comprehensive design to workplace satisfaction through need-supply fit. This study considers the differences of co-designed scenarios through atmospheres, which are different in the studied meeting scenarios and also for individual work and recovery events. Thus, the results of the co-designed atmosphere indicate that the need for an atmosphere is a potential attribute for need-supply fit studies. The atmosphere poses a challenge as a research attribute because it is not as easily definable as, for example, privacy. However, the atmospheres can be accessed through the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of comprehensive design.

Discussion and conclusions

The post-pandemic workplace design cannot be fully grounded on previous expertise and evidence because employee requirements towards work environments have changed. Therefore, it is important to collect timely information on employee needs and integrate them into design practices. This study approaches workplace design and research through a theory-informed workplace design framework consisting of comprehensive design through perceived and analytical viewpoints and experience of comprehensive design through need-supply fit formation and workplace satisfaction. Also, this study examines the design of spatial atmosphere and its impact on workplace satisfaction as a perceived dimension of comprehensive design.

Practitioners often base spatial features of design decisions, such as atmosphere and aesthetic choices, on their personal experience of design, visited buildings and internet searches (Bae et al., Citation2019). Finding ways to communicate the spatial features between employees and designers in the co-design context is important for increasing the designers' understanding of the situation from employees’ perspectives and preferences. The need for the atmosphere was used in this research to guide the co-design communication and design process to achieve workplace satisfaction formation in the intervention area. The framework served as a communication tool for discussing design-related information at a level that describes them in sufficiently general terms. It also produced design information on a level that enabled the integration of employee needs and preferences into the design to support workplace satisfaction formation.

The analysis of the collected design information from the co-design process revealed that the participants’ perception of atmosphere and spatial characteristics contained information on the symbolic and instrumental design dimensions. Therefore, a facilitated discussion was a necessary step in this co-design process to collect more detailed information on the aesthetic dimension of the space. Understanding aesthetic preferences is important in designing a satisfactory spatial atmosphere. Furthermore, the atmosphere descriptions served as beneficial metaphors for the design process when the co-design information was interpreted and implemented into the design.

Recent studies (Chafi et al., Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022) indicate the importance of social interaction at the workplace, which often occurs in the meeting rooms and breakout areas that are studied in this case study. This study produced co-designed information on spatial atmospheres for meeting rooms and breakout areas. The distinct atmosphere needs towards, for example, creative and technical meetings indicate that the perceived atmosphere may be an important addition to work environment research, such as the need-supply fit studies because they often combine activity, spatial surroundings, and different needs towards the environment. Employee perceptions of the atmosphere in different spaces may be important in multilocational work environments because the environment influences employees’ workplace location choices. Furthermore, the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of the environment may impact whether employees choose a space that supports their tasks and activities. More research is needed to comprehensively understand whether the user needs and preferences are common across organizations during different activities concerning spatial atmospheres.

Previous research has focused on objectively measurable factors in workplace satisfaction studies (Candido et al., Citation2016; Maarleveld et al., Citation2009) or preferred quantitative approaches to study subjective experience. This leaves details of comprehensive design undefined, for example, narrowing the complex entity of workplace aesthetics into a single question item (Forooraghi et al., Citation2023). The metareviews, such as Bergefurt et al. (Citation2022), show that attributes impacting the spatial atmosphere, such as colours and lighting, are studied in limited settings, or the studies are focused on single attributes. Extending the concept of comprehensive design further from the physical comprehensive design into perceived and analytical comprehensive design enables studying the attributes and artefacts of workplace design as entities. Therefore, this study suggests that further research is performed concerning employee needs and preferences towards perceived comprehensive design through the spatial atmosphere to understand its role in need-supply fit and satisfaction formation.

Limitations

The research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may impact the results compared to post-pandemic workplace design. Furthermore, this study researches complex interrelations of work environment design through a single case study in which design solutions and empirical results cannot be generalized to other organizations. Rather, more case studies are needed to provide guidelines towards spatial atmospheres for different activities. The co-design processes are traditionally organized in face-to-face settings, providing opportunities for using different materials and creative toolkits that support full interaction between organizers and participants. Zoom-mediated workshops significantly limited the use of traditional tools and interactions, which likely impacted the workshops’ outcomes. However, this technology allowed researchers to organize multiple workshops, inviting fewer participants per workshop and being able to focus on all participants and interact with them fully.

The co-design research approach produced a rich dataset, which is important for understanding the complex relationships of design attributes, artefacts, and their qualities and how employees perceive them as part of the comprehensive workplace experience. Nevertheless, the study presents a theory-informed design framework that provides future opportunities to study the dimensions of comprehensive design in other organizations to inform their workplace design processes and work environment experience research.

Implications for research

The changes brought about by the pandemic and multilocational working may hinder existing workplaces from meeting the criteria for satisfaction and need-supply fit supporting workplaces. It is, therefore, essential to develop methods that support design processes and enable more efficient integration of employees’ current needs into the design. The post-pandemic workplace redesign is also a compelling time for research because it offers ample opportunities to study the design processes. However, to study workplace design, it is essential to understand what kind of information designers collect and use in design to understand whether the designers make informed design choices and if they need new tools for design processes. Based on this study, a design-linked, theory-informed framework supports a wider collection of design-related information for research purposes to gain a deeper understanding of the productivity and well-being supporting factors of work environments.

Implications for practice

This paper presents several implications for practice. The results indicate that grounding the co-design methodology in a theory-informed workplace design framework supports collecting design information that combines the activity, surrounding environment, user needs and preferences to support workplace satisfaction. The employees and designers have different perspectives on the designed environment; thus, the communication and co-design, through the activities, emotions and spatial atmosphere, enable both stakeholders to share the same vision of the designed scenario and create a basis for a more detailed understanding of the design outcome. The framework also offers ample opportunities to communicate the design needs and solutions in more detail to achieve the best outcomes. The theory-informed workplace design framework may support designers to analytically understand needed design goals and desired outcomes in workplace design.

Authors contributions

Markkanen led the planning, data collection, intervention design and data analysis. Markkanen wrote the paper, and Herneoja provided comments on the early version of the article. Herneoja led the Academy of Finland research project, where the material for the paper was collected. Aale Luusua and Ville Paananen are acknowledged for their valuable comments on the article.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonini, M. (2021). An overview of Co-design: Advantages, challenges and perspectives of users’. Involvement in the Design Process. Journal of Design Thinking, 2(1), 45–60. https://jdt.ut.ac.ir/

- Appel-Meulenbroek, R., Kemperman, A., van de Water, A., Weijs-Perrée, M., & Verhaegh, J. (2022). How to attract employees back to the office? A stated choice study on hybrid working preferences. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 81, 101784–101795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101784

- Babapour Chafi, M., Harder, M., & Bodin Danielsson, C. (2020). Workspace preferences and non-preferences in activity-based flexible offices: Two case studies. Applied Ergonomics, 83, 102971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102971

- Bae, S., Bhalodia, A., & Runyan, R. C. (2019). Theoretical frameworks in interior design literature between 2006 and 2016 and the implication for evidence-based design. The Design Journal, 22(5), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1625177

- Barton, G., & Le, A. H. (2023). The importance of aesthetics in workplace environments: An investigation into employees’ satisfaction, feelings of safety and comfort in a university. Facilities, 41, 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1108/F-03-2023-0016

- Bergefurt, L., Weijs-Perrée, M., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., & Arentze, T. (2022). The physical office workplace as a resource for mental health – A systematic scoping review. Building and Environment, 207(Part A), 108505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108505

- Beute, F., & de Kort, Y. A. W. (2014). Salutogenic effects of the environment: Review of health protective effects of nature and daylight. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 6(1), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12019

- Binder, T., De Michelis, G., Ehn, P., Jacucci, G., Linde, P., & Wagner, I. (2011). Design things (eBook). The MIT Press. https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

- Blomberg, D., & Karasti, H. (2012). Ethnography: Positioning ethnography within participatory design. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 106–136). Routledge.

- Bodin Danielsson, C. (2015). Aesthetics versus function in office architecture: Employees’ perception of the workplace. Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, 27, 11–40.

- Bodin Danielsson, C., & Bodin, L. (2008). Office type in relation to health, well-being, and job satisfaction among employees. Environment and Behavior, 40(5), 636–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916507307459

- Böhme, G. (2017). Atmospheric architectures: The aesthetics of felt spaces (T. Engels-Schwarzpaul, Ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bosch-Sijtsema, P. M., Ruohomäki, V., & Vartiainen, M. (2010). Multi-locational knowledge workers in the office: Navigation, disturbances and effectiveness. New Technology, Work and Employment, 25(3), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2010.00247.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brunia, S., De Been, I., & van der Voordt, T. J. M. (2016). Accommodating new ways of working: Lessons from best practices and worst cases. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 18(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-10-2015-0028

- Budie, B., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., Kemperman, A., & Weijs-Perree, M. (2019). Employee satisfaction with the physical work environment: The importance of a need based approach. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 23(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijspm.2019.6372

- Busciantella-Ricci, D., & Scataglini, S. (2024). Research through co-design. Design Science, 10, 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2023.35

- Candido, C., Gocer, O., Marzban, S., Gocer, K., Thomas, L., Zhang, F., Gou, Z., Mackey, M., Engelen, L., & Tjondronegoro, D. (2021). Occupants’ satisfaction and perceived productivity in open-plan offices designed to support activity-based working: Findings from different industry sectors. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 23(2), 106–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-06-2020-0027

- Candido, C., Kim, J., De Dear, R., & Thomas, L. (2016). BOSSA: A multidimensional post-occupancy evaluation tool. Building Research and Information, 44(2), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2015.1072298

- Canepa, E. (2022). Architecture is atmosphere. Notes on empathy, emotions, body, brain, and space. Mimesis International.

- Chafi, M. B., Hultberg, A., & Yams, N. B. (2022). Post-pandemic office work: Perceived challenges and opportunities for a sustainable work environment. Sustainability, 14(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010294

- Chan, X. W., Shang, S., Brough, P., Wilkinson, A., & Lu, C. q. (2023). Work, life and COVID-19: A rapid review and practical recommendations for the post-pandemic workplace. In Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 61(2), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12355

- Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 15(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326969ECO1502_5

- Colenberg, S. E. (2023). Beyond the coffee corner - Workplace design and social well-being [Delft University of Technology]. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:51968bff-1313-437f-8e36-0966cf6b19e0.

- Colenberg, S., & Jylhä, T. (2022). Identifying interior design strategies for healthy workplaces – A literature review. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 24(3), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-12-2020-0068

- Colenberg, S., Jylhä, T., & Arkesteijn, M. (2021). The relationship between interior office space and employee health and well-being – A literature review. Building Research & Information, 49(3), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2019.1710098

- De Been, I., & Beijer, M. (2014). The influence of office type on satisfaction and perceived productivity support. Journal of Facilities Management, 12(2), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-02-2013-0011

- Edwards, J. R., Caplan, R. D., & Van Harrison, R. (1998). Person-environment fit theory: Conceptual foundations, empirical evidence, and directions for future research. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of organizational stress (pp. 28–67). Oxford University Press.

- Elsbach, K. D., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). The physical environment in organizations. The Academy Management Annals, 1(1), 181–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/078559809

- Elsbach, K., & Stigliani, I. (2019). The physical work environment and creativity. In O. Ayoko & N. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Organizational behaviour and the physical environment (pp. 13–36). Routledge.

- Forooraghi, M., Miedema, E., Ryd, N., & Wallbaum, H. (2020). Scoping review of health in office design approaches. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 22(2), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-08-2019-0036

- Forooraghi, M., Miedema, E., Ryd, N., Wallbaum, H., & Babapour Chafi, M. (2023). Relationship between the design characteristics of activity-based flexible offices and users’ perceptions of privacy and social interactions. Building Research & Information, 51, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2023.2180343

- Gerdenitsch, C., Korunka, C., & Hertel, G. (2018). Need-supply fit in an activity-based flexible office: A longitudinal study during relocation. Environment and Behavior, 50(3), 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517697766

- Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Psychology Press.

- Gjerland, A., Søiland, E., & Thuen, F. (2019). Office concepts: A scoping review. Building and Environment, 163(August), 106294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106294

- Griffero, T. (2022). They are there to be perceived: Affordances and atmospheres. In Z. Djebbara (Ed.), Affordances in everyday life (pp. 85–95). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08629-8_9

- Groen, B., van der Voordt, T., Hoekstra, B., & van Sprang, H. (2019). Impact of employee satisfaction with facilities on self-assessed productivity support. Journal of Facilities Management, 17(5), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-12-2018-0069

- Halford, S. (2005). Hybrid workspace: Re-spatialisations of work, organisation and management. New Technology, Work and Employment, 20(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2005.00141.x

- Haynes, B. (2008). Impact of workplace connectivity on office productivity. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 10(4), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/14630010810925145

- Hoendervanger, J. G., De Been, I., Van Yperen, N. W., Mobach, M., & Albers, C. (2016). Flexibility in use: Switching behaviour and satisfaction in activity-based work environments. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 18(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-03-2013-0017

- Hoendervanger, J. G., Van Yperen, N. W., Mobach, M. P., & Albers, C. J. (2019). Perceived fit in activity-based work environments and its impact on satisfaction and performance. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101339

- Hoff, E. V., & Öberg, N. K. (2015). The role of the physical work environment for creative employees – A case study of digital artists. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(14), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.971842

- Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1993). The biophilia hypothesis. Island Press.

- Kirillova, K., Fu, X., & Kucukusta, D. (2020). Workplace design and well-being: Aesthetic perceptions of hotel employees. Service Industries Journal, 40(1–2), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1543411

- Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redstrom, J., & Wensveen, S. (2011). Design research through practice : from the Lab, field, and showroom (eBook). Morgan Kaufmann.

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-Job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

- Maarleveld, M., Volker, L., & van der Voordt, T. J. M. (2009). Measuring employee satisfaction in new offices – the WODI toolkit. Journal of Facilities Management, 7(3), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/14725960910971469

- Maier, J. (2011). Affordance based design: Theoretical foundations and practical applications. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller GmbH & Co. KG.

- McCoy, J. M., & Evans, G. W. (2005). Physical work environment. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. R. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of work stress (pp. 219–246). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412975995.n9

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. Doubleday.

- Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions, 6(3), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1145/301153.301168

- Plowright, P. D. (2014). Revealing architectural design: Methods, frameworks and tools. Routledge.

- Radun, J., & Hongisto, V. (2023). Perceived fit of different office activities – The contribution of office type and indoor environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 89, 102063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102063

- Rafaeli, A., & Vilnai-Yavetz, I. (2004a). Emotion as a connection of physical artifacts and organizations. Organization Science, 15(6), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0083

- Rafaeli, A., & Vilnai-Yavetz, I. (2004b). Instrumentality, aesthetics and symbolism of physical artifacts as triggers of emotion. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 5(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463922031000086735

- Roggema, R. (2017). Research by design: Proposition for a methodological approach. Urban Science, 1(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci1010002

- Rolfö, L., Eliasson, K., & Ek, J. A. E. (2017). An activity-based flex office: Planning processes and outcomes. 48th Annual Conference of the Association of Canadian Ergonomists: 12th International Symposium on Human Factors InOrganizational Design and Management (pp. 330–338).

- Rothe, P., Lindholm, A.-L. L., Hyvönen, A., Nenonen, S., Lindholm, A.-L. L., & Hyvönen, A. (2011). User preferences of office occupiers: Investigating the differences. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 13(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/14630011111136803

- Sander, E., Caza, A., & Jordan, P. (2014). A framework for understanding connectedness, instrumentality and aesthetics as aspects of the physical work environment. Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management, 1–33.

- Sander, E., Caza, A., & Jordan, P. (2019). Psychological perceptions matter: Developing the reactions to the physical work environment scale. Building and Environment, 148, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.11.020

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner : how professionals think in action. Basic Books, cop.

- Sirola, P., Haapakangas, A., Lahtinen, M., & Ruohomäki, V. (2022). Workplace change process and satisfaction with activity-based office. Facilities, 40(15/16), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/f-12-2020-0127

- Snodgrass, A., & Coyne, R. (1996). Is designing hermeneutical? Architectural Theory Review, 2(1), 65–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264829609478304

- Søiland, E. (2021). De-scripting office design: Exploring design intentions in use. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 23(4), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-10-2020-0039

- Stappers, P. J. (2007). Doing design as a part of doing research. In R. Michel (Ed.), Design research now (pp. 81–91). Birkhäuser. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7643-8472-2_6

- van der Voordt, T. (2004). Productivity and employee satisfaction in flexible workplaces. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 6(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/14630010410812306

- Verbeke, J. (2013). This is research by design. In F. Murray (Ed.), Design research in architecture : An overview (pp. 137–159). Ashgate.

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I., Rafaeli, A., & Yaacov, C. S. (2005). Instrumentality, aesthetics, and symbolism of office design. Environment and Behavior, 37(4), 533–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916504270695

- Vischer, J. C. (2007). The effects of the physical environment on job performance: Towards a theoretical model of workspace stress. Stress and Health, 23(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1134

- Withagen, R., Araújo, D., & de Poel, H. J. (2017). Inviting affordances and agency. New Ideas in Psychology, 45, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2016.12.002

- Withagen, R., de Poel, H. J., Araújo, D., & Pepping, G. J. (2012). Affordances can invite behavior: Reconsidering the relationship between affordances and agency. New Ideas in Psychology, 30(2), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.12.003

- Wohlers, C., & Hertel, G. (2017). Choosing where to work at work – towards a theoretical model of benefits and risks of activity-based flexible offices. Ergonomics, 60(4), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2016.1188220

- Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., Weston, J., Joyce, C., Shah, N., Sherman, K., Hecht, B., & Teevan, J. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

- Yang, E., Kim, Y., & Hong, S. (2021). Does working from home work? Experience of working from home and the value of hybrid workplace post-COVID-19. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 25(1), 50–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-04-2021-0015

- Zhong, W., Schröder, T., & Bekkering, J. (2022). Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 11(1), 114–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.07.006