ABSTRACT

In 2012, Africa RISING conducted participatory community analysis (PCA) as the first phase of a participatory development approach in the Ethiopian highlands. The PCA identified trends, constraints, and opportunities – and shed light upon how farmers perceive livelihoods to be changing. Inputs, diseases, pests, soil fertility, post-harvest management, and fodder shortages were seen as challenges, while off-farm income has become increasingly important. Gender differences in livestock and crop preferences for food security and income sources were observed. PCA established development priorities in a way that researchers may have approached differently or missed, providing research development priorities for Africa RISING scientists.

En 2012, « Africa Rising » a conduit une évaluation communautaire participative (PCA) qui constituait la première phase d'une approche participative de développement sur les hauts plateaux éthiopiens. Cette évaluation a permis d'identifier des tendances, des contraintes et des opportunités – et apporté un éclairage sur la manière dont les agriculteurs perçoivent les changements dans leur vie. Les contributions, les maladies, les parasites, la fertilité des sols, la gestion post-récolte et les pénuries de fourrage étaient perçues comme des difficultés, alors que les revenus non-agricoles sont de plus en plus importants. Concernant les préférences en matière d'élevage et de cultures, relativement à la sécurité alimentaire et aux sources de revenus, des différences de genre ont été observées. La PCA a permis d'établir des priorités de développement, dans une approche que les chercheurs auraient pu utiliser différemment ou ignoré, et de ce fait éclairé les scientifiques de Africa Rising sur les priorités pour la recherche en développement.

En 2012, como parte de la primera etapa de un enfoque de desarrollo participativo en las tierras altas de Etiopía, África rising realizó un análisis comunitario participativo (acp). Éste identificó tendencias, limitaciones y oportunidades, clarificando en qué sentido los campesinos perciben que sus medios de vida están transformándose. Aspectos tales como insumos, enfermedades, plagas, fertilidad de la tierra, gestión posterior a la cosecha y forraje, fueron calificados como desafíos, constatándose que los ingresos conseguidos fuera de la parcela se han vuelto cada vez más importantes. Asimismo, en lo que respecta al tipo de ganado y cultivos como opciones para garantizar la seguridad alimentaria y las fuentes de ingreso, se detectaron diferentes preferencias vinculadas al género. El acp estableció prioridades de desarrollo que los investigadores pudieron haber abordado de manera diferente o podrían no haber notado, estableciéndose así preferencias —dirigidas a los científicos vinculados a África rising— a la hora de investigar el desarrollo.

Introduction

Ethiopia is an agricultural nation experiencing remarkable growth amidst persistent food insecurity. Ethiopia still imports grain to feed itself, and nearly 40% of its population are undernourished or food insecure (Von Grebmer et al. Citation2014). The agronomic, economic, social, and environmental constraints to farming are very important across Ethiopia, as agricultural performance is a major determinant of food security (Ferede et al. Citation2013; Motbainor, Worku, and Kumie Citation2016). Many additional factors influence agricultural performance and food security in Ethiopia, including access to technology and markets, agronomic and environmental conditions, pest and disease pressures, socio-economic status, and institutional and policy constraints. However, information on these factors is scarce in Ethiopia and sub-Saharan Africa in general.

Crop–livestock systems in Ethiopia require context-aware development efforts to effectively meet community needs. Ethiopia has a diversity of languages, ethnic groups, religions, and topography including altitude, rainfall, temperature, and soil type (Yimer, Ledin, and Abdelkadir Citation2006). Farm-level decisions can vary with geography and environment, thus context-aware approaches to agricultural research are potentially more likely to be successful in areas with diverse agro-ecologies and social backgrounds (Lyon et al. Citation2011). This article describes an approach to sustainable intensification in the Ethiopian highlands as part of the Africa Research in Sustainable Intensification for the Next Generation (Africa RISING) project, designed to improve farm and landscape practices, markets, food security, and livelihoods in a participatory manner sensitive to critical socio-cultural and environmental contexts.

Participatory approaches to development

An increasing desire to improve accountability to the rural poor has encouraged development approaches that include communities in problem identification, project planning, and implementation of solutions – instead of simply telling smallholders what to do. Agricultural development pathways are influenced by both extrinsic and intrinsic factors, which are location specific (Meijer et al. Citation2015), and benefit from inclusive and locally adapted strategies. Participatory approaches were designed with this in mind, aiming to empower communities to identify and prioritise development challenges, and to improve the genesis and adoption of solutions.

Participatory approaches embody a shift in strategy towards building human resources and empowering communities throughout the agricultural research and development agenda. Such approaches in agriculture utilise an array of different participatory methodologies and tools, including farmer field schools, farmer-to-farmer extension, agroecosystems analysis (AA), participatory rural appraisal (PRA), and rapid rural appraisal (RRA). Participatory approaches, employing packages of methodologies and tools, are intended to operationalise community-based farmer-to-farmer extension and joint learning through a specific framework. These approaches, including the participatory research and extension approach (PREA) (Kamara et al. Citation2008), can effectively deliver scientific research to farmers, empower local ownership, and boost technology adoption. Using PREA, extension agents serve as facilitators instead of instructors, and guide the process by which farmers solve their own challenges. For example, PREA has been successfully used in Nigeria to improve weed management (Chikoye et al. Citation2007) and control Striga hermonthica (Kamara et al. Citation2008). Participatory methods have been used to empower stakeholders in ways that conventional development approaches do not.

While participatory approaches can be deployed in positive ways, it is also important to acknowledge their limitations. First, building relationships and encouraging equitable communication is not an instantaneous process. There can be social, political, or economic contexts that even seasoned field agents might not completely understand when facilitating a discussion or a meeting. Establishing trust between programmes and beneficiaries requires long-standing investment in and maintenance of relationships in the face of unexpected challenges. In addition, projects that are wholly designed before implementation risk “mining” their constituents for information instead of co-designing interventions. Further, while participatory approaches can amplify marginalised voices, power relationships between stakeholders may not necessarily change themselves (Schut et al. Citation2015). Participatory development cannot follow a specific protocol, and must instead adapt to challenges as they present themselves.

This article presents work conducted by Africa RISING in the Ethiopian highlands, using PREA to identify limitations to sustainable agricultural development, and to prioritise solutions while building capacity and partnerships to effectively implement those solutions. This describes an early opportunity for Ethiopian scientists involved in Africa RISING to interface with farmers, use shared experiences to inform and develop research activities, and to build a foundation for deploying additional participatory tools in future engagements with target communities.

Africa RISING and PREA

Africa RISING is a research-for-development initiative led by Consultative Group for International Research (CGIAR) partners, working to improve food, nutrition, and income security among agricultural households in the Ethiopian highlands. It utilises PREA to identify, troubleshoot, and alleviate problems in highland crop–livestock agricultural systems. PREA provides farmers with opportunities to identify factors constraining their livelihoods, to capture the context of problems across different locales, and to build the foundation for collaborative problem solving.

Four key stages in using PREA are: community engagement and mobilisation; joint action planning with target communities; on-farm implementation and experimentation; and monitoring, experience sharing, and lesson learning. Under Africa RISING, community engagement included a participatory community analysis (PCA) at kebele level (a kebele being the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia), where community stakeholders identified significant challenges to agricultural livelihoods within their communities. The PCA was important in identifying different livelihood strategies from farmers’ perspectives across spatially and demographically diverse areas of the highlands, and to see how these livelihoods have been evolving. Further, the PCA captured crop and livestock priorities across gender and kebeles, and provided a forum for farmers to identify key challenges related to crops and livestock, and to discuss how to address them.

The PCA had five primary objectives: (a) knowledge sharing and information gathering on key community livelihoods, particularly on crop and livestock production systems, processing, and marketing; (b) identification of constraints to livelihood improvements; (c) identification of available technologies, opportunities for improvement, coping strategies, and entry points for strengthening sustainable livelihoods and food security; (d) identification of kebele-based organisations and local leaders to form innovation platforms (IPs); and (e) utilisation of the PCA findings to guide the development of the Africa RISING research agenda.

Agricultural IPs have been employed in sub-Saharan Africa to promote integrated agricultural research for development (IAR4D) efforts in a context-specific, community empowering manner, to unite diverse stakeholders in creating strong returns to development investments, and to spur institutional change (Schut et al. Citation2015). Building a foundation for the establishment of IPs was an important goal of the PCA, as the IPs would represent a diverse partnership to enhance multi-directional knowledge transfer, intervention planning, experimentation, and monitoring and evaluation. These multi-stakeholder IPs would facilitate expansion beyond participatory research into improved power dynamics and community agency, addressing complex problems through an adaptive and self-deterministic framework. Initially, Africa RISING R&D agents would actively facilitate IP establishment, but would quickly transition to a consultative role.

Materials and methods

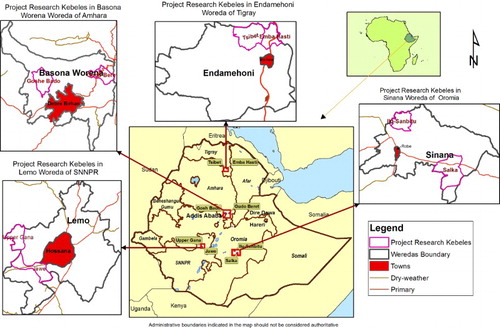

The PCA was initiated after two-day training in Addis Ababa to outline methods and familiarise resource persons with the tools to be used. In each of the four Ethiopian Africa RISING sites, eight resources persons were designated from local and CGIAR partners. Following the workshop, the PCA was conducted over a three-week period between 20 June and 6 July 2012 in eight research kebeles across four woredas (districts) in four different regions (), taking three to four hours per day over two to three days in each kebele.

It was recognised that the Ethiopian highlands are extremely diverse topographically, climatically, in respect of population distribution and accessibility of markets. The delineation of the study sites was undertaken on the basis of administrative boundaries, the size being large enough to encompass a range of bio-physically defined areas with contrasting farming systems and a range of social institutions, as well as including two kebeles in each region. Following initial selection of wheat-producing woredas, further stratification was undertaken on the basis of elevation, rainfall, and population density, as well as market access in order to include a wide spectrum of variability (). Further bio-physical and socio-economic characterisation of the study sites was undertaken as part of a detailed baseline study at a later stage.

Table 1. Location and characterisation of PCAs by region, woreda, and kebele, showing the number of participants.

Participation in the PCA discussions was arranged by local extension staff in conjunction with kebele leadership, involving 30 to 40 people in each kebele. This provided an opportunity not only to undertake the PCA, but also importantly to introduce Africa RISING. No attempt was made at this early stage in the PREA process to characterise participants, other than by gender and age. However, participants were asked what criteria were generally used by the community to differentiate households, these being categorised by five asset or capital types (). Although these varied between kebeles, three broad household categories were identified, namely poor, medium, and better resourced. However, no attempt was made to link these to either constraints or opportunities. The resource categories were intended for use later in the PREA cycle as more detailed joint farmer–researcher planning took place.

Table 2. Criteria for assessing household differences identified during the PCA by participants.

Discussion groups were facilitated by multi-disciplinary teams from partner universities, research institutions, and regional and zonal bureaus of agriculture in separate groups of men, women, and young men. Since considerably more men participated than women, as often occurs in local meetings, it was not possible to form groups of younger women. Information from group meetings was then shared in general meetings, allowing men and women to share their different gender and age perspectives on the topics discussed.

The discussion groups provided a gender-neutral space to talk about potentially sensitive topics. Discussion topics included livelihood sources and trends on- and off-farm, reasons for shifts in livelihood strategies, crop and livestock priorities and challenges, value chain analyses of important farming-based livelihoods, existing water availability, and opportunities for improvement across these topics. The PCA also assessed whether crop-based livelihood activities were more highly prioritised for food security or for sale as a cash crop, and asked participants to rank their priorities for future intervention. These areas of discussion were standardised across PCAs through qualitative discussion tools used by each team of facilitators.

Crops were identified and ranked by participants for food and income across kebeles and genders. Challenges to crop and livestock production were identified through value chain analyses of ten community-identified crops, with men, women, and youth groups selecting commodities of the highest priority to them: Barley – in two kebeles, Carrots – one, Enset (Ensete ventricosum) – two, Faba bean – six, Maize – one, Pepper – one, Potato – four, Teff ( Eragrostis tef ) – one, Sasula (Impatiens tinctoria) – one, Wheat – six; as well as five livestock types: Cow – in four kebeles, Donkey – four, Ox - four, Sheep – six, Poultry – two. These value chain analyses were facilitated by a tool that asked participants to identify challenges (ranked by priority), coping strategies, and opportunities for each crop across the following stages of the value chain: input procurement, production, storage, processing, and marketing. Value chain analyses framed further discussion of the most pressing production challenges.

At the end of each meeting, discussions were held among farmers and resource persons on how to link stakeholders into IPs that could spearhead future improvements. The identification of local and externally based institutions in each kebele important for agricultural development provided opportunities for linking different organisations to coordinate R&D activity. Subsequent to the PCA, these linkages have been strengthened into active IPs functioning at both strategic (woreda) and implementation (kebele) levels.

Data were collected during the PCA process with guidance from facilitators. This included the use of pairwise ranking or show of hands in less contentious cases and completed using standardised tables during group discussions, and shared in general discussion. The number of times livelihood strategies, crop production challenges, and livestock production challenges were prioritised were tallied to compare the relative importance within each of these categories. Likewise rankings of livestock types and crops for both cash and food security across genders were tabulated to compare their relative importance, then analysed for differences in mean ranking between cash and food purposes using R, employing both the t-test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (Wilcoxon Citation1945). Comparisons of means that were different than zero in both tests at p < 0.05 were reported as significant. Lastly, the most important institutions for agriculture were calculated as the percentage of respondents that identified each institution, split by gender.

The PCA provided the first step of Africa RISING’s PREA process, which was instrumental in shaping Africa RISING’s research agenda. In combination with the PCA, additional methodological tools, including key informant interviews, household typology building, and a quantitative baseline data were undertaken. Only the results of the PCA are presented here.

Results

Knowledge sharing on community livelihoods

The PCA identified trends and perceptions of key livelihoods, with 42 livelihoods described as static, improving, or declining across communities (). Vegetables production was cited the most times as an important livelihood source, followed by wheat, faba bean, milk production, equines for transport, and potatoes. The number of times each livelihood source was prioritised varied across kebeles. For example, vegetable production, important for women and youth – although the most commonly mentioned livelihood source in four of the eight research kebeles – was the least commonly mentioned in Salka kebele, where equines for transport ranked first, providing opportunities for young men. Blacksmithing, selling stone, home construction, and banana production were all mentioned just a single time in a single kebele as an important livelihood, and were not considered important in other kebeles. Non-agricultural livelihoods were often considered increasing, while the production of many essential food security crops was perceived to be stable or in decline. For instance, buying and selling goods and remittance transfers were always reported as increasing in importance, followed by the sale of eucalyptus timber (where grown), labouring for others, making and selling local drinks, and transport using equines ().

Figure 2. Number of times a livelihood source was prioritised and described as stable, improving, or declining across kebeles.

Table 3. Main livelihood trends by region and kebele.

Crops considered to be decreasing or mainly decreasing due to disease problems or poor market conditions included enset, barley, maize, potatoes, sorghum, faba bean, and field peas. Enset was considered to be on the decline primarily due to disease pressure, while sorghum, dairy, and field pea followed as most consistently decreasing in importance. Crop-based livelihoods considered to be mainly increasing due to favourable market conditions included lentils, sasula, sugar cane, teff, and vegetables. Sasula is a high value crop used for cosmetics, grown in the two kebeles of Endamehoni woreda, and serves as an important cash crop. Chickpea and coffee, although mentioned in only two kebeles, were considered to be static due to disease. Factors thought to be influencing livelihood trends most commonly centred on changing prices and demand, disease, and an increased need for cash in the household.

It was important to differentiate between crops planted for income and those planted for consumption and household food security. The relative importance of different crops for cash and food security by men, women, and young men is presented in and . There were significant differences between the importance of many individual crops for cash and food purposes in different kebeles, which were commonly described by agro-ecological suitability, gender, and age preferences. Barley was ranked as having the highest importance for food security in six kebeles and then ranked low for cash, across gender and age groups in all kebeles. Other crops ranked highly for food included wheat, faba beans, barley, teff, and maize. Important for cash were teff, wheat, lentils, potatoes, and faba beans. The crops important for cash and food consumption included teff, wheat, and faba bean, with potatoes, field peas, lentils, and vegetables ranked as more important for income than for food.

Table 4. Crop preference ranking for cash by men/women/youth and kebele (1 = highest rank).

Table 5. Crop preference ranking for food security by men/women/youth and kebele (1 = highest rank).

There were differences between the food and cash rankings of less commonly mentioned crops as well, highlighting further specialisation between crop-based livelihoods. For instance, chat (Catha edulis), grown and chewed with a mild stimulant effect, had no utility as a food source and was only mentioned once as a cash priority. Vegetables including cabbage, pepper, garlic, haricot beans, onions, and rough pea were often ranked as relatively important for cash by women, but of low importance for food security. In many cases, specific vegetables were grown for a specific market opportunity. For example, garlic was grown in only one kebele, where it was ranked second for cash importance by women but only seventh for food security.

Livestock priorities showed important differences across genders and youth (). Overall rankings, but with important gender and age preferences, in order of decreasing importance were oxen, cows, sheep, donkeys, poultry, goats, horses, mules, and lastly bees for honey. Although there were differences between kebeles, oxen were consistently highly ranked by men – less so by women and younger men. Cows and poultry, often managed by women, cows for milk and butter, and poultry for eggs and meat were ranked highly by women. Small ruminants were also ranked highly by women and less so by men. Equines, especially donkeys and horses, were ranked lower than cattle and small ruminants but were regarded as essential for transport by young men.

Table 6. Livestock preference ranking by men/women/youth and kebele (1 = highest rank).

Identification of constraints to livelihood improvements

Per the results of value chain analyses in PCA discussions, crop and livestock production challenges are reported in and . For crops, three of the four most commonly identified challenges were related to agricultural inputs: access to quality seed, high fertiliser costs, and limited access to agrochemicals (). The other top-four challenge was disease and pest pressure. Weed pressure was another major production-related problem, followed by lack of rainfall and perceived impacts of climate change. Storage and processing, particularly pest damage, lack of extension and knowledge sharing, and insufficient storage infrastructure, were commonly reported as well. Lastly, marketing challenges were many and varied, but consistently illustrated a lack of access to technical information and resources, information asymmetry, and market weaknesses.

Challenges identified with livestock showed similar tendencies to crop production (). Input problems (including grazing land) were most commonly mentioned, highlighting lack of access to feed, veterinary products, clinics, and improved breeds and artificial insemination technology. Also important were production challenges, led by livestock disease, housing and hygiene, and predation. Problems associated with prices and the inability to participate in functioning markets were similarly reported for livestock, as they were for crops. Production challenges were broadly similar in each area, with men, women, and youth prioritising crops and livestock important to them. Men tended to consider cereal and cash crops, with women more concerned with legumes and food crops, giving priority to cows, poultry, and small ruminants.

Identify opportunities for strengthening sustainable livelihoods

The highest priority areas for future intervention, in response to the cross-cutting problem areas and trends identified across kebeles by the PCA in objectives one and two, are presented in . For crop-based livelihoods, the highest priority areas included improving community-based seed multiplication, improving soil fertility and reducing erosion, and improving household nutrition through promotion of fruit and vegetable production. For livestock, the highest priority areas included the improvement of animal feeding, building linkages with agro-vet suppliers, and improving processing capacity for dairy operations. Building interlinked watershed protection plans to improve water access was a crosscutting priority area. Priority rankings were similar across all regions, with men, women, and youth again prioritising technologies relevant for livelihoods important to them.

Table 7. Priorities for future interventions and monitoring.

Identify organisations and leadership, building a basis for IPs

PCA participants prioritised over 70 institutions as important for agricultural production, based either within or outside the kebele but conducting operations inside the kebele (). These institutions collectively provide a variety of important services, such as agro-inputs on credit, improved water, education and health support, and access to kebele development agents. For organisations based within the kebele, the most commonly mentioned as important for agriculture included woreda and kebele-based administration offices for agriculture and farmer training centre offices, churches and/or mosques, welfare-focused community-based organisations (CBOs) particularly Edir and Eikub, the kebele health clinic, and local schools. Edir is an association established among neighbours or workers to raise funds for emergencies, while Eikub is an association established by a small group to provide rotating funding to improve livelihoods. Outside the kebele, the woreda administration was mentioned the most often as important for agricultural activities, followed by NGO and government projects. Institutions prioritised less frequently included cooperative unions, research organisations, banks, credit and savings associations, and local markets. Women and youth identified a wider range of institutions, while men were often more hesitant in their suggestions, prioritising woreda- and kebele-based administrations and cooperatives over NGOs and CBOs.

Figure 5. Institutions identified as important for agriculture, ranked by percentage of respondents (men, women, and youth).

Africa RISING facilitated forming IPs from key identified institutions within each research site, to work from a systemic perspective and prioritise farmers’ needs and opportunities. Strategic IPs formed at the woreda (district) level focus upon higher levels of change-making, promoting innovation in specific value chains and facilitating operational IPs. Operational IPs coordinate local development activities, serve as innovation clusters for on-farm R&D, and are entry points for additional interventions. In contrast to IPs that focus on single commodities, Africa RISING IPs address innovations within broader crop–livestock systems, taking into account institutional, social, and policy contexts that affect sustainable intensification and food security. Each IP was supported by a technical group providing training, linkages and learning, and assistance with cross-cutting themes such as gender. IPs engaged in regular activities as part of PREA to boost participatory capacity, and collaboratively build on PCA results.

Utilise PCA findings to guide development of Africa RISING research agenda

The PCA results provided community-based evidence and perspectives to anchor the development of the Africa RISING research agenda, as well as the protocols and tools to be employed in Africa RISING interventions. Seven key themes were identified for clustering Africa RISING’S research activities in the Ethiopian highlands: (1) feed and forage development; (2) field crop varietal selection and management; (3) integration of high-value products into mixed farming systems; (4) improved land and water management for sustainability; (5) improved efficiency of mixed farming systems through crop–livestock integration; (6) cross-cutting problems and opportunities; and (7) knowledge management, exchange, and capacity development. Based on these themes, 15 Africa RISING action-oriented research protocols were developed ().

Table 8. Africa RISING research protocols.

Discussion

Knowledge sharing on community livelihoods

Information gathered by this PCA illustrates the evolving pressures facing smallholders, and the imperative for development agents to recognise and adapt to the shifting rural landscape. For example, women ranked dairying and faba bean as important activities – livelihood sources that have been the target of many past interventions – yet both were said to be in decline: dairying due to reduced availability of grazing land, and faba bean due to disease. If these pressures continue, the viability of these key livelihoods will be increasingly tenuous. While wheat, vegetables, and equine transport were on the rise due to favourable market conditions, the fastest improving livelihood strategies were trading activities, remittances, and the eucalyptus sector – all off-farm income sources. Even in agricultural areas, the PCA showed that practitioners must incorporate increasingly important non-agricultural opportunities.

Faba bean, wheat, barley, teff, and potatoes were the most commonly prioritised crops for both income and household use, but the fact that three were reported to be on the decline – faba bean, potatoes, and barley – is a significant concern. The primary driver for decline in each of these three crops was identified as crop disease, suggesting that farm-level disease management capacity is insufficient across a variety of crops and locales. This indicates that there may be an opportunity to synergistically improve regulatory, storage, and seed production capabilities across multiple crop types.

The PCA highlighted the importance of context specificity, even as broader themes emerge. For instance, garlic was only mentioned once each as a food and a cash source, but was ranked second most important for income when it was mentioned. Also, the fact that eucalyptus was considered a food priority despite its inedibility may indicate that eucalyptus holds specific uses for food security, such as augmenting incomes to purchase food during the hunger season. Indeed, it is important to simultaneously consider both scalable interventions that apply broadly, and smaller-scale priorities that might not match with regional trends.

Gender differences across livestock, particularly in how men, women, and young men regarded poultry, cows, oxen, small ruminants, and equines, indicate that it would be prudent for livestock-focused interventions to work with gender and age sensitivities. Men ranking oxen higher than women follows traditional roles where men are primarily responsible for activities requiring draft power (Ogato, Boon, and Subramani Citation2009). Conversely, poultry production requires lower levels of economic and traditional social capital and is often the responsibility of women and youth (Gebremedhin et al. Citation2016), which was reflected in the higher ranking of poultry among these groups. Because cows and dairy production are highly prioritised by women, interventions to increase dairy productivity and improve marketing are likely to supplement female incomes. Additionally, opportunities for young men as transport contractors using donkeys and mules are likely to be popular within that demographic.

Identification of constraints to livelihood improvements

PCA results point to a wide-ranging insufficiency in the seed multiplication and distribution chains for food crops, cash vegetable crops, and dual-purpose cash and food crops. Both men and women identified limited input access as a constraint across many crop-based livelihoods. Although fertilisers, herbicides, pesticides, and seeds were accessible through cooperatives and local vendors in some cases, they were often reported as prohibitively expensive, adulterated, counterfeit, or ineffective. Input access was also insufficient for livestock, including veterinary drugs, improved breeds, feed, and productive grazing land.

Seed system capacity could be improved for most crops through the establishment of semi-formal seed certification schemes, or strengthening the innovation capacity of actors within the system. Improving input provision, including credit and contract mechanisms, might be implemented in ways that benefit multiple crop and livestock strategies simultaneously. Further, consistent marketing challenges indicate a potential lack of access to technical skills and resources, information asymmetry, and weak market linkages.

Worryingly, but not surprisingly, both men and women identified a broad tranche of constraints that either directly or indirectly can be expected to worsen under a changing climate. First, farmers reported increasingly erratic rainfall and more frequent droughts and floods. Second, pests and diseases were seen as problematic both for production and storage. The effects of climate change on pests and diseases are poorly understood, but may increase through a number of different mechanisms (Gornall et al. Citation2010). Third, declining soil fertility and increased soil erosion was recognised as contributing to production declines. Climate change may exacerbate erosion and/or soil fertility challenges in developing countries (St. Clair and Lynch Citation2010). Fourth, inadequate access to draft power and farm equipment results in late land preparation and planting, which hinders yields. These results indicate that addressing near-term insufficiencies with seed system and with input access should be combined with increased climate resilience.

Identify opportunities for strengthening sustainable livelihoods

It is important to continue to consider the interrelationships between problem areas identified above, as trying to remove a single barrier may be obstructed by limitations affecting other areas. For example, adoption of a new crop production technology may be prevented by inadequate access to information, seed supply, or an unfavourable policy environment (Asfaw et al. Citation2012). Conversely, there may be areas that can be targeted for improvement simultaneously to alleviate multiple pressures. These positive and negative pressure points can more readily be identified when working in an iterative participatory mode, as farmers understand and can communicate the realities experienced on the ground.

Continued monitoring of problem areas identified by the PCA will offer insight into the effects of interventions and the adoption of new practices, as well as how pressures upon agricultural livelihoods change. Intervention priority rankings are presented in , which provided the groundwork upon which future Africa RISING interventions were established. Approaches to sustainable intensification in the Ethiopian highlands, Africa RISING included, should consider priority areas and rural interventions as deeply interlinked and set within complex systems, and should be approached with systems thinking in an adaptive learning mode whenever possible.

Identify organisations and leadership, building a basis for IPs

Kebele members currently have limited understanding of which services are provided by which institution, which complicates efforts to coordinate. It is important to develop a collaborative environment across diverse stakeholders to facilitate capacity building, the implementation of sustainable solutions, and institutional innovation (Schut et al. Citation2015). Farmer-to-farmer technology diffusion and innovation will require the IP to select and mentor lead farmers, while local seed producers will need support to produce accessible, quality seed of well-adapted improved varieties. This represents a strong intersection between participatory development and traditional agricultural R&D.

The CGIAR system explicitly recognises the need to include all stakeholders along the “farmer–research–development” pathway, and IPs provide a mechanism to unify diverse actors under common cause. Partnership across IP institutions addresses high-priority challenges in an integrated and innovative way, working more effectively than strictly bottom-up or top-down strategies. Further, recognition of institutional influence upon development agendas can push beyond historical blinders. The IP structure is collaborative, much like participatory approaches in general, which can have transformative benefits but can be slow and require commitment and maintenance to yield results.

Utilise PCA findings to guide development of Africa RISING research agenda

Perhaps most importantly, the PCA provided a farmer-based foundation for the development of the Africa RISING research agenda. Farmer livelihoods and perceptions generated in the PCA provided an essential context and focus for the interventions to follow, and gave insight into how agricultural livelihoods are evolving across the Ethiopian highlands. This is highly relevant to the success of food security, development, and health initiatives. Given the complexity of agricultural systems and constraints, it is important to embed farmers in the identification, evaluation, and dissemination of food security solutions.

In order to avoid poor diffusion of solutions or misalignment between farmer needs and project activities, it was essential that farmer opinions carry weight early in the planning process of the Africa RISING research agenda. Inadequate local input has led to problems with agricultural development projects in Ethiopia in the past, as the issues that experts prioritise may in some cases dominate other challenges more relevant from farmers’ perspectives (McGuire Citation2008). In conjunction with other tools and approaches employed by Africa RISING – including key informant interviews, household typology building, and quantitative baseline data – the PCA identified problem areas that may have otherwise been missed, strengthened partnerships, and provided a pathway for capacity building and problem solving through IPs.

While the development community has encountered many of the issues identified in the PCA before, the PCA provided opportunities for communities to identify key agricultural challenges and link them to solutions in a self-directed manner. The Participatory Forest Management approach utilised in Ethiopia since the 1990s is an example of how community inclusion can translate into rural empowerment, increased equity, and reduced land degradation (Gobeze et al. Citation2009), which applied similar principles to Africa RISING’s agricultural development approach. Africa RISING now continues along its PREA cycle, implementing interventions developed through the PCA and IP process, which will be reported in subsequent articles.

Conclusions

The landscape of agricultural livelihoods in Ethiopia is shifting, and participatory approaches can help farming communities and development practitioners to adaptively align development strategies within evolving contexts. PCA not only served to identify and target challenges and trends in the highlands, but also returned agency to communities to better control development pathways.

While livelihood sources and challenges varied geographically, multiple priorities were consistently observed. Non-agricultural income streams are becoming increasingly important, while key crop value chains are threatened. Issues of input acquisition, pest and disease pressure, soil infertility, and post-harvest challenges were similarly themed across livestock and crop production. Gender differences in the importance of small ruminants, poultry, and oxen were revealed, as were differences in the utility of specific crops for food or household income. While local-scale context remains very important, the PCA revealed opportunities to systematically address barriers that cut across multiple crop and livestock types, such as seed system development, input provision, and climate resilience. The establishment and facilitation of IPs through local partner capacity building, not only in production and marketing but also training and policy advocacy skills, will build on these results through adaptive problem identification and problem solving.

The Africa RISING project has been enriched through participatory methods, and will leverage this experience to better implement participatory approaches in the future. Africa RISING has observed how participatory approaches can unite diverse stakeholders to identify focal points for intervention, and amplify the voices of farmers, including women and youth. Interventions clarified through the PCA were unlikely to have emerged in the absence of a participatory approach. However, it is recognised that participatory processes can require additional expense, a degree of adaptability and openness, and a longer timeline, which can be difficult given tight deadlines and deliverable requirements. The PCA served as an early opportunity for Ethiopian scientists involved in Africa RISING to interface with farmers, inform, and develop research activities, and build a foundation for iterative partnership in the future. Although participatory methods may not be appropriate in all situations, Africa RISING is a case where the challenges were strongly outweighed by the benefits – producing actionable information and relationships to improve food security and livelihoods.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Feed the Future Initiative for their generous financial support of Africa RISING.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Tobias Lunt is an independent researcher based at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA.

Jim Ellis-Jones is a professional Agriculturalist with specific expertise in participatory research and extension methods, at Agriculture-4-Development, Silsoe, UK.

Kindu Mekonnen is a Crop-Livestock Systems Scientist working at the International Livestock Research Institute, Ethiopia.

Steffen Schulz is a Project Manager at Deutsche GIZ GmbH, Ethiopia.

Peter Thorne is a Senior Scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute, Ethiopia.

Elmar Schulte-Geldermann is the Leader of Seed Potato for Africa Program at the International Potato Center, Kenya.

Kalpana Sharma is a Plant Pathologist at the International Potato Center, Ethiopia.

ORCID

Tobias Lunt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9901-4191

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asfaw, S., B. Shiferaw, F. Simtowe, and L. Lipper. 2012. “Impact of Modern Agricultural Technologies on Smallholder Welfare: Evidence from Tanzania and Ethiopia.” Food Policy 37 (3): 283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.02.013

- Chikoye, D., J. Ellis-Jones, T. Avav, P. M. Kormawa, U. E. Udensi, G. Tarawali, and O. K. Nielsen. 2007. “Promoting Integrated Management Practices for Speargrass (Imperata Cylindrica (L.) Raeusch.) in Soybean, Cassava and Yam in Nigeria.” Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment 5 (3/4): 202.

- Ferede, T., A. Belayneh Ayenew, M. A. Hanjra, and M. Hanjra. 2013. “Agroecology Matters: Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Implications for Food Security in Ethiopia.” In Global Food Security: Emerging Issues and Economic Implications 71–112. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Gebremedhin, B., E. Tesema, A. Tegegne, D. Hoekstra, and S. Nicola. 2016. “Value Chain Opportunities for Women and Young People in Livestock Production in Ethiopia: Lessons Learned.” Accessed April 5, 2017. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/78636.

- Gobeze, T., M. Bekele, M. Lemenih, and H. Kassa. 2009. “Participatory Forest Management and Its Impacts on Livelihoods and Forest Status: The Case of Bonga Forest in Ethiopia.” International Forestry Review 11 (3): 346–358. doi: 10.1505/ifor.11.3.346

- Gornall, J., R. Betts, E. Burke, R. Clark, J. Camp, K. Willett, and A. Wiltshire. 2010. “Implications of Climate Change for Agricultural Productivity in the Early Twenty-First Century.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365 (1554): 2973–2989. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0158

- Kamara, A. Y., J. Ellis-Jones, P. Amaza, L. O. Omoigui, J. Helsen, I. Y. Dugje, N. Kamai, A. Menkir, and R. W. White. 2008. “A Participatory Approach to Increasing Productivity of Maize Through Striga Hermonthica Control in Northeast Nigeria.” Experimental Agriculture 44 (03): 349–364. doi: 10.1017/S0014479708006418

- Lyon, A., M. M. Bell, C. Gratton, and R. Jackson. 2011. “Farming Without a Recipe: Wisconsin Graziers and New Directions for Agricultural Science.” Journal of Rural Studies 27 (4): 384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.04.002

- McGuire, S. J. 2008. “Path-Dependency in Plant Breeding: Challenges Facing Participatory Reforms in the Ethiopian Sorghum Improvement Program.” Agricultural Systems 96 (1–3): 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2007.07.003

- Meijer, S. S., D. Catacutan, O. C. Ajayi, G. W. Sileshi, and M. Nieuwenhuis. 2015. “The Role of Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions in the Uptake of Agricultural and Agroforestry Innovations among Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 13 (1): 40–54. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2014.912493

- Motbainor, A., A. Worku, and A. Kumie. 2016. “Level and Determinants of Food Insecurity in East and West Gojjam Zones of Amhara Region, Ethiopia: A Community Based Comparative Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Public Health 16 ( June): 503. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3186-7

- Ogato, G. S., E. K. Boon, and J. Subramani. 2009. “Gender Roles in Crop Production and Management Practices: A Case Study of Three Rural Communities in Ambo District, Ethiopia.” Journal of Human Ecology 27 (1): 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2009.11906186

- Schut, M., L. Klerkx, M. Sartas, D. Lamers, M. McCampbell, I. Ogbonna, P. Kaushik, K. Atta-Krah, and C. Leeuwis. 2015. “Innovation Platforms: Experiences with Their Institutional Embedding in Agricultural Research for Development.” Experimental Agriculture FirstView ( October): 1–25.

- St.Clair, S. B., and J. P. Lynch. 2010. “The Opening of Pandora’s Box: Climate Change Impacts on Soil Fertility and Crop Nutrition in Developing Countries.” Plant and Soil 335 (1-2): 101–115. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0328-z

- Von Grebmer, K., A. Saltzman, E. Birol, D. Wiesman, N. Prasai, S. Yin, Y. Yohannes, P. Menon, J. Thompson, and A. Sonntag. 2014. Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hidden Hunger. Vol. 83. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Wilcoxon, F. 1945. “Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods.” Biometrics Bulletin 1 (6): 80–83. doi: 10.2307/3001968

- Yimer, F., S. Ledin, and A. Abdelkadir. 2006. “Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen Stocks as Affected by Topographic Aspect and Vegetation in the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia.” Geoderma 135 ( November): 335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.01.005