ABSTRACT

Although plant clinics are considered an important mechanism in the service delivery to farmers, not much is known about their functioning in the daily reality of plant doctors and farmer-clients. This article reports on an exploratory study describing the functioning of eight plant clinics in Rwanda. Personal and organisational commitment, publicity, and proactive communication with farmers and local leaders are key factors explaining higher attendance of some clinics. Farmer attendance is under-reported by 40–50%. Data management needs improvement to make clinic records reliable tools for decision-makers. This type of assessment can help improve operations and realise the plant clinics’ potential.

Introduction

As elsewhere in developing countries, pests and diseases are a major constraint to agricultural productivity in sub-Saharan Africa (Vurro, Bonciani, and Vannacci Citation2010). Agrochemical dealers are often farmers’ only available source of information and advice when a crop problem emerges. Insufficient knowledge about the relevant pests and diseases may lead to misdiagnoses and inappropriate use of pesticides, resulting in excessive production costs and occasional development of pesticide resistance as well as increase in the incidence of secondary pest outbreaks (Mahr, Whitaker, and Ridgway Citation2008). Many small-scale farmers in Africa lack access to timely advice and information on how to deal with plant health problems.

In order to address this challenge, plants clinics were started in a number of countries from 2005 onwards (Boa Citation2009; Plantwise Citation2015). A plant clinic is a simple service located in a rural area, mostly market places, cooperatives, or community premises, where agricultural extension workers trained as “plant doctors” provide general plant healthcare such as diagnostics and advice on any problem (biotic or abiotic) on any crop for everyone who needs the advice, free of charge (Boa Citation2009). The plant clinics differ from other extension approaches, such as farmer field schools and other group-based methods, in two ways: they offer an open, regular service (typically once a week or fortnightly) and demand is defined by the queries farmers present at the clinic (Danielsen et al. Citation2013). The establishment of plant clinics as regular rural services is believed to have significant potential to improve farmers’ ability to take timely action against new or endemic pests, as evidenced by a growing body of studies and testimonies (Hirschfeld, Davis, and Ezeomah Citation2016).

Rwanda is one of the countries that have embraced plant clinics as a means to enhance the country’s preparedness to deal with plant health threats. Since 2011, plant clinics have been operational through collaboration between the Rwanda Agriculture Board (RAB) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI), Ministry of Local Government (MINALOC), and Plantwise, a global CABI-managed programme to support the establishment of durable plant health services for farmers.Footnote1 Various districts are implementing plant clinics in collaboration with RAB. There are now 66 plant clinics in Rwanda run by 217 trained plant doctors (RAB Citation2014). The clinics are well aligned with Rwanda’s National Agricultural Extension Strategy, which promotes “multi-approach and multi method extension” in order to meet farmers’ diverse needs for extension services (MINAGRI Citation2009). RAB and MINALOC consider the plant clinics a valuable means to improve plant health advisory services for farmers and to strengthen disease vigilance at the field level, thereby contributing to reducing crop losses caused by plant health problems. The relevance of the plant clinics was confirmed by a survey from 2015 showing that more than 90% of interviewed clinic users were satisfied or very satisfied with the services provided, and referred to plant clinics as their main source of crop health information (Nsabimana, Uzayisenga, and Kalisa Citation2015). According to the Plantwise Online Management System (POMS), a global repository of plant clinic data used to estimate attendance, around 60% of the Rwandan plant clinics register an average of less than five farmer queries per clinic session, while only 20% of the clinics register an average of over seven queries per session.Footnote2 Similar attendance figures are observed in Ghana, Malawi, and Zambia (unpublished data). So far little is known about the reasons for differences in clinic attendance within and between countries. One of the few published studies, from Uganda, found that plant clinics operated by NGO–local government alliances were less affected by the unconducive policy and institutional environment that shapes agricultural extension. This partly explained why these alliances were better able to sustain higher farmer attendance compared to plant clinics operated by local governments alone (Danielsen and Matsiko Citation2016).

Despite the rapid increase in number of plant clinics and widespread agreement about their unique role and potential for targeting an unmet farmer demand, there is limited information on the daily practice around the implementation of plant clinics. Most information deals with attendance, farmer profiles, and type of queries. By exploring the functioning of the daily practice of implementation and consultation, this article seeks to identify possible benefits and potential improvements to the way these plant health advisory services function. We therefore examined the operations of selected Rwandan plant clinics in order to identify key factors that influence the patterns of farmer attendance at plant clinics. We discuss the scope of plant clinics for meeting farmer demand for plant health advice in the context of Rwanda’s agricultural extension policies.

Methodology

This study had an exploratory character and aimed to capture the way the selected clinics operate through the experiences of both plant doctors and farmer-clients during the visits. We selected eight cases (clinic sites) from different parts of the country for observations and conducted 49 interviews in total. This yielded a description with a mix of qualitative and quantitative data. In order to identify factors that influence farmer attendance three domains were examined (adapted from the framework by Danielsen and Matsiko Citation2016): clinic operations (staffing, publicity, funding, logistics, personal and institutional commitment); farmers’ perceptions (quality, relevance, visibility, timeliness); and accuracy of the clinic records. Methods included: direct observation of plant clinic sessions; semi-structured interviews with farmers, plant doctors, clinic coordinators and the national data manager; and review of plant clinic records. The two latter staff categories comprise RAB staff at either regional or central level, who have also received plant doctor training.

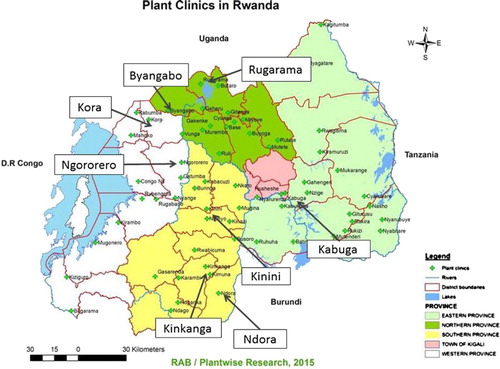

Eight plant clinics were selected based on the number of clinic queries recorded in POMS from April 2015 to March 2016 (, ): four clinics with low attendance (≤5 queries per session on average) and four with high attendance (>7 queries per session on average). The definition of low and high attendance was based on an overall analysis of available POMS data for all Rwandan plant clinics as well as the generally accepted notion by the RAB clinic coordination of the high–low cut-off point. Five of the clinics operate from market places and three from village centres (two mobile clinics and one fixed clinic). Four of the selected plant clinics use a tablet for recording.

Table 1. Characteristics and location of plant clinics selected for the study.

Each of the eight plant clinics were visited once over a period of six months from April to September 2016. A total of 11 plant doctors were followed during these sessions to observe how they organised and carried out their work and how they engaged with farmers during live plant clinic “consultations” (plant doctor–farmer interactions). The plant doctors were interviewed about the plant clinic operations, the constraints they face and what possible solutions they envision. Five plant clinic coordinators and the national data manager were interviewed about clinic operations and record keeping. Two plant clinic users and two non-users (men and women) were interviewed at each clinic site (32 in total). They were selected among farmers visiting the clinics and market people, respectively. They were asked about their perceptions and experiences with the plant clinics as well as their reasons for attending or not. Write-ups from interviews and observations were compiled for analysis. Information about clinic regularity, farmer attendance, and gender patterns was drawn from POMS and plant clinic logbooks and compared between the two. The examined factors were grouped into high, partial, or low according to their relative importance to explain differences in farmer attendance.

Plant clinic operations in Rwanda

RAB is the main organisation responsible for plant clinic activities under the Plantwise programme. The plant clinics are manned by “plant doctors” who are extension workers employed by district local governments and who have received two three-day training courses on field diagnosis, delivery of plant health advice, and plant clinic operations. Usually, there are two plant doctors present per plant clinic, a Sector Agronomist (SA) and a Socio-Economic Development Officer (SEDO). Sessions of 3–4 hours are held twice a month. The clinics are a simple physical set up consisting of a table, some chairs, an umbrella, a banner, examination tools, factsheets, and basic reference materials. Plant clinics use various means to advertise the clinic sessions: farmer meetings including lead farmers, extension workers, banners, and megaphones.

The plant doctors take notes about farmer queries (crops, diagnosis, and advice) in a prescription form, recording information in paper form or electronically using a tablet. The plant doctors using tablets write a short recommendation on a piece of paper given to farmers who don’t have a telephone or are unfamiliar with them. Farmers who have a telephone and know how to use it receive the recommendations in a short SMS message. In the paper-based plant clinics farmers receive a copy of the prescription form. This information is also recorded in the Plantwise Online Management System (POMS) with the intention to make it available for use by different agricultural stakeholders in the country (RAB Citation2014). The plant doctors also keep a logbook to register basic information about the clinic session: start and end time, number of male and female farmers attended, and the number of queries received during the session.

What do the plant clinic records reveal?

First, we explored the plant clinic data to find patterns in farmer attendance and regularity of clinic sessions.

summarises the number of queries presented at the eight plant clinics according to the data recorded in POMS (Part A) and the logbooks (Part B). The totals (far right column) show similar attendance patterns of the two dataset, with the logbook numbers being slightly higher (1,139) compared to the POMS numbers (1,022). Yet, when comparing the query numbers across clinics and months, several differences appear. Sometimes the POMS numbers are higher, sometimes the logbook numbers. Not all “empty” months are the same for the two datasets. This is partially due to the fact that the data reporting periods are slightly different for the two systems: POMS is updated on the twentieth day of the month and the logbook records on the thirty-first day, in both cases through the Zonal Coordinators (interview with the Plantwise National Data Manager, January 2017). Yet this does not fully explain the differences in query numbers.

Table 2. Number of farmer queries attended at the selected plant clinics per month according to POMS (Part A) and logbooks (Part B).

Further data discrepancies were revealed as we compared the number of sessions held per clinic and the average number of queries received (). While the two datasets are fairly similar for Ngororero, Kora, and Byangabo clinics, there are larger differences for the rest. POMS recorded a larger number of sessions, in total 150 sessions compared to 119 in the logbooks, a difference of ∼26%. Conversely, for seven of the eight plant clinics, the average number of queries/session was higher for the logbook data compared to POMS. The overall difference was ∼40%. In the case of Kinini and Kabuga, both categorised as low-attendance clinics, the average number of queries was remarkably high; however, these averages were based on only three sessions for each clinic.

Table 3. Total number of clinic sessions and average number of queries per session as recorded in POMS and the logbooks.

While POMS only registers the number of queries, the logbooks also register the number of visiting farmers. On average, each farmer brought 1.09 queries to the clinic sessions (data not shown), which shows that the number of queries seems to be a fairly accurate estimate of farmer attendance.

Neither of the two data sources for clinic attendance showed clear gender differences between high- and low-attendance clinics: the participation of male farmers was higher in all clinics, with an overall male–female distribution of 61–39% (data not shown).

Farmer attendance was only partially related to plant clinic regularity (). According to the POMS data, six plant clinics held 20 or more sessions in the study period, which is close to full compliance with the planned schedule (24 sessions in a year). Among the four low-attendance clinics, Kinini and Kabuga reported fewer sessions while Byangabo and Kora plant clinic reported as many sessions as the high-attendance clinics, but they received fewer clients.

The plant doctors and clinic coordinators gave various reasons for the discrepancies between the two databases. Filling a prescription form, which is the basis of the POMS data, is considered time consuming (approximately 15 minutes per form, by observation), and is therefore not always done, especially when there are farmers waiting or when several farmers present the same problems. The last is often the case since approximately 40% of all POMS queries examined here were on maize stalk borer and cassava viruses (data not shown). A plant clinic coordinator explained:

“If ten farmers present a problem with maize stalk borer, it feels pointless to the plant doctor to fill ten prescription forms with the same information. In these cases they often give group advice to save time. Sometimes the number of farmers is recorded in the logbook, sometimes not.” (Plant clinic coordinator, January 2017)

“It is difficult to say, because when the tablets were introduced in May 2015, the ten best-performing plant clinics were chosen to participate in the pilot so they already had a good turnout. But the tablets definitely save time and bring the data more quickly into the system.” (Plantwise National Coordinator, September 2016)

Plant clinic operations and farmer perspectives

Clinic staffing

The total number of formally assigned staff to each clinic and the degree of staff rotation in the study period did not differ much between low- and high-attendance clinics. Most plant clinics had a SA and a SEDO as plant doctors most of the time. As an exception, Kinini plant clinic had only one plant doctor from its establishment in April 2014 up to June 2016. The SAs were not always at the clinics, since they were often busy with other activities.

The plant clinics dealt with the effects of workload and competing obligations of the plant doctors in different ways. At the four high-attendance plant clinics, the absence of one plant doctor did not stop the plant clinic session from running, as their colleague would run the plant clinic alone. In contrast, we observed that Kabuga and Kinini clinics (low attendance) were cancelled more often when one of the plant doctors was absent. The reasons for cancellation were occasionally noted in the logbooks. These included participation in meetings, training, itorero (cultural training), or genocide memorial.

Publicity and visibility

Overall, high-attendance plant clinics tended to have better publicity and higher visibility compared to the lower attendance clinics. Some plant doctors emphasised the importance of good personal communication with farmers and farmers groups. The Rugarama and Ngororero plant doctors, for example, were proactive in their communication with farmers. One explained how they organise their work.

“The plant clinic session day is known by the farmers and sector authorities because we include it in our action plan. We sometimes change the operating time when we have urgent activities from our organisation. In such a case we inform the farmer promoters so that they can tell the farmers the exact time that we will be available.” (Rugarama plant doctor, June 2016)

“Sometimes I see the plant clinic session and other times I don’t see it. So I get confused about the operating time.” (Plant clinic user, Kinini plant clinic, May 2016)

The location of the plant clinics in the market also appeared to influence the effectiveness of the publicity. Some did not have a suitable location. For example, Kinini plant clinic was placed behind the market which meant that most farmers returned to their homes without reaching the clinic site or even being aware of its existence.

Using the village chief and cell executive secretary (“cell” is the administrative unit preceding village level) for advertising the plant clinics had a positive effect according to the plant doctors of Ndora, Kinkanga, Rugarama, and Ngororero (high-attendance) plant clinics. They explained that these authorities are more trusted and respected by the farmers than other persons working in or outside the institution. In some plant clinics, both high and low attendance (e.g. Kinini and Ndora), farmer promoters announced the clinic operation day to fellow farmers after the Umuganda programme (a type of community work) every last Saturday of the month. Only Kinkanga plant clinic used a megaphone during the study period to spread the message: “Here we give advice on crop health for free.” We observed that farmers came to the plant clinic while the megaphone was on (visit to Kinkanga plant clinic, 20 April 2016), with 14 farmers attending the clinic that day (data not shown).

Perceptions from non-clinic users demonstrated the challenges of getting a clear message across to potential clients. A client from the Rugarama plant clinic told how she was ridiculed by some of her fellow farmers:

“There are some people who are informed about this plant clinic but they don’t come. They were laughing at me one time I was coming here with samples. What I did, I stayed calm and told them that the disease cannot recover without showing it to the doctor. Some farmers may stop coming here after being ridiculed by fellow farmers.” (Rugarama plant clinic user, June 2016)

Logistics and funding

All plant clinics had similar logistics and funding conditions. Staff time is fully covered by RAB and local governments. The plant doctors who are employed as SA normally get 69,500 Rwandese francs (RWF) (= ∼US$86) per month from the local government to cover transport and communication costs related to all field work (of which the clinic sessions are only a small part), which they considered sufficient.Footnote3 They also get a motorcycle as part of their job. In contrast, the SEDO get half the amount for communication compared to the SA but no transport allowance or motorcycle. The plant doctors who are employed as SEDO said that this is not enough to cover the plant clinic activities, even with the additional allowance of 5,000 RWF (= ∼US$6.3) provided by Plantwise to each plant doctor per clinic session. Some of the plant doctors (from both high- and low-performing clinics, such as Kinkanga and Kinini) occasionally use their own means for transport, airtime, and to pay for manpower for carrying and cleaning the materials, while others transport the materials themselves (e.g. Kora). We observed that all plant clinics, except Kinkanga, had stopped using the megaphone because of the cost of batteries (1,050 RWF=∼US$1.3). This is despite megaphones being perceived by the plant doctors as one of the best ways to make farmers aware about the plant clinics.

Organisational and personal commitment

Overall, there was a notable difference in the commitment shown by the districts and the individual plant doctors. At the time of the study, the plant clinics had been included in the institutional work plans of RAB but not of the district local governments. In Kinkanga, Ndora, Rugarama, and Ngororero (high attendance), the plant clinic work was part of the formal 2015–16 performance contract of the plant doctors. This was not the case in the low-attendance clinics, although the Kabuga plant clinic was in the plant doctors’ action plan.

Despite the formalisation of the plant doctor role in some districts, the plant clinics were still largely regarded as a “RAB project” by local government managers, making it in practice an appendix to their core activities. This, together with the limited operational funds available to the SEDOs, appeared to affect the plant doctors’ commitment, especially at low-attendance clinics, to mobilise farmers and run the clinic. So far there has been limited involvement of District Agronomists (DA) in the plant clinics (only the DA of Ngororero is a plant doctor) which signals limited institutional ownership and incentives to get involved. The DA is a crucial link to the local government authorities in order to achieve their sustained buy-in to the plant clinics. The case of Kinkanga plant clinic also demonstrates the limited district ownership. Unlike the year before, the plant clinic work was not included in the 2016–17 performance contract of the plant doctors because the SA (also a plant doctor) who had been highly influential in formalising the plant clinic was transferred to another sector.

The importance of personal commitment was apparent from the interviews. Plant doctors having a large number of farmers attending their plant clinics explained that first of all, they are committed and they like their job. They feel they own the plant clinics (interviews with plant doctors from Kinkanga, Rugarama, Ngororero and Ndora, April to September 2016). Second, they involve farmer promoters in mobilisation (see previous section), and third, they talk about the plant clinics in every encounter with the farmers. They said that to be successful, it is necessary to be enthusiastic and self-motivated. They also mentioned that they support each other as a team and try to be consistent in running the plant clinics, even if there is something going wrong, for instance with the logistics or competing tasks.

Quality and relevance of advice

There was no apparent variation in farmers’ satisfaction with the clinic advice between high- and low-attendance clinics: there was positive and negative feedback across all clinics. All interviewed clinic users said that they trust the recommendations given by the plant doctors. Several of them were return users who came back with more queries:

“It is my third time I visit this plant clinic because it is important to me. Here we get advice on our plant health problems. Most of the farmers who don’t attend this plant clinic go directly to buy pesticides which sometimes are not recommended for the pest and disease. But here, we become sure on the treatments that we are using.” (Female farmer, Kinini plant clinic, May 2016)

“To come or not at the plant clinics is the same. My fellow farmers showed the problem they have in their cassava and banana crops but up to now there is no solution.” (Non-user, Kinkanga plant clinic, April 2016)

Discussion

The daily practice of implementation and consultation

The observations on the functioning of the plant clinics, the way plant doctors and clients meet and exchange information showed how the clinic sessions are operating in a context full of personal and institutional constraints. Small expenses for the operation, like the cost of new batteries for the loudspeaker, can be sensitive and frustrating points for the officers who are in charge. The comments of interviewed farmers about the usefulness of the advice, and the farmers’ inability to act on it because they do not have access to chemical “plant remedies”, are another example that help us to understand the operation of these clinics in their context. This understanding goes beyond attendance numbers and is essential for explaining the impact and potential of this innovative approach to service delivery.

Farmer attendance

The study findings present a mixed picture of reasons why there are consistent differences in attendance between plant clinics. We categorised the examined factors in three groups – high, partial and low importance – according to their relative importance to explain the differences in farmer attendance (). Other factors not addressed here are likely also to influence farmer attendance, such as distance from the farmers’ home to the clinic, crops grown, purpose of growing, and socio-economic status of farmers.

Table 4. Overview of examined factors and their relative importance to explain differences in farmer attendance at eight selected plant clinics.

All the plant clinics had fairly similar basic conditions in terms of staffing, logistics, and funding. Yet there was a notable difference between high- and low-attendance clinics in terms of organisational and personal commitment. The plant doctors from the high-attendance clinics appeared to be more proactive and creative in publicising the plant clinics, communicating with farmers and engaging local leaders. They also generally had a stronger team spirit, supporting and helping each other with logistics and coping with workload. Some of the low-attendance clinics opted more easily for cancelling clinic sessions if one of the plant doctors was absent or operational funds were not available or insufficient, which indicates poor accountability. Institutional buy-in – evidenced by the inclusion of the plant clinics in the plant doctors’ performance contracts – was found to be of major importance to motivate and support the plant doctors. The organisational commitment and positive clinic staff attitude mutually reinforced each other, thus signalling the existence of a supportive environment.

Staff stability was overall fairly good in the study period which also contributed to consistency in clinic operations for most plant clinics. The correlation between clinic regularity and farmer attendance gave a mixed picture. Two of the low-attendance clinics (Kora and Byangabo) were as regular as the high-attendance clinics (). These findings are vastly different from neighbouring Uganda, where clinic irregularity was closely related to low farmer attendance (Danielsen and Matsiko Citation2016).

The plant doctors recognised the need to improve the clinic publicity. The fact that more than half of the non-users (62%) had not heard of the plant clinics confirms that the clinic providers face a major challenge in making the clinics visible and creating sufficient awareness about this new type of service within farming communities. Similar figures have been found among non-users in Uganda (Brubaker et al. Citation2013) and Malawi (Mandula et al. Citation2016). Comments from non-users such as “plants cannot have clinics” or “I don’t need the service” show that it will require some effort to explain and demonstrate what the plant clinics are and what they can do.

We did not find a correlation between quality and relevance of the advice and farmer attendance. There was predominantly positive feedback from clinic users, but also negative comments from both high- and low-attendance clinics. The most common complaints referred to farmers’ inability (with or without advice from plant clinics) to manage important diseases such as cassava viruses and banana bacterial wilt and the lack of inputs at the plant clinics. Similar observations have been made in Malawi (Mandula et al. Citation2016) and Uganda (Mur et al. Citation2015) where some farmers did not feel served because the plant clinics could not provide the required “medicine”. These challenges are largely beyond the scope of the plant clinics. Plant doctors need to manage farmers’ expectations to avoid disappointment, while engaging in collective action with other key stakeholders to solve these major problems.

Although there were no apparent differences in gender patterns between clients from low and high-attending clinics, female farmers were largely under-represented, comprising on average only 31% of all clients. This confirms findings from various countries, including Rwanda, that women generally have less access to plant clinics due to differences in gender roles, education, and asset ownership (Kilalo, Olubayo, and Toroitich Citation2014; Mur et al. Citation2015; Mandula et al. Citation2016; Silvestri and Musebe Citation2016). The local governments and RAB need to pay attention to the gender dimension to ensure equitable access to the information provided by plant clinics for all farmer groups, men and women alike.

Plant clinics in Rwanda are still not fully integrated into the core extension activities of local governments. They are largely seen as a complementary project partially dependent on funding from Plantwise. The project status is reinforced by the fact that RAB is the organisation with overall responsibility for plant clinic activities, while the local governments figure as collaborators. Local governments are responsible for a wide range of activities (e.g. health, social protection, education, and community development), while RAB focuses on agriculture only. It is likely that the leading role of RAB limits the local governments’ sense of engagement and accountability towards plant clinic operations compared to their core activities. The fact that SAs were not always present in the clinics because they were often busy with other activities shows that the local governments do not fully “own” the plant clinics.

Integration and ownership

In order to strengthen the role and status of the plant clinics, the district authorities need to take over responsibility by including them in institutional work plans, budgets and performance contracts. However, this will only happen if the local governments see the added value of the plant clinics and if they fit into the existing structures and work dynamics. Ngororero local government is showing signs of organisational ownership through the committed involvement of the District Agronomist who helps to run the plant clinic. This study did not look specifically at the coordination between RAB and the local government, but other studies have highlighted the challenges of establishing effective plant clinic coordination across institutions. Experiences from Uganda show that inter-ministerial plant clinic coordination was hindered by differences in mandates, roles and management procedures, as well as poor accountability and incentive systems and weak enforcement of regulations (Danielsen, Matsiko, and Kjær Citation2014). To what extent this applies to Rwanda too cannot not be deduced from this study. However, RAB and local governments need to address the aspects of capacity, organisation, and governance in order to reap the mutual benefits of their collaboration.

The current policy and institutional environment in Rwanda seems highly conducive for embedding plant clinics into the diverse “extension landscape”. In contrast, the institutionalisation of plant clinics in Uganda has been challenged for years by an unstable policy environment as well as incompatible institutional mandates and extension approaches (Danielsen, Matsiko, and Kjær Citation2014). According to the National Agricultural Extension Policy (MINAGRI Citation2009), the Government of Rwanda actively supports the development of pluralistic services and the use of diversified methods and approaches to address the many needs of farmers for advice and information. Since 2012, the government has made a significant effort to strengthen agricultural extension through the expansion of the Twigire Muhinzi (TM) extension model which is based on farmer field schools (FFS) and farmer-to-farmer extension. This has led to a notable increase in the proportion of rural households accessing advice, up from 32% to 69% (Wennink and Mur Citation2016). The TM extension system provides a valuable skills base and organisational structure which the plant clinics can benefit from and vice versa. Farmer promoters could, for example, assist as “plant nurses” or “nursing aids” to address well-known, easy-to-diagnose problems. There are ongoing efforts to train FFS facilitators as plant doctors in order to create synergies between the different types of extension services and enhance the clinics’ resilience to staff turnover and workload (interview with the Plantwise National Coordinator).

This evidence suggests that there is significant potential to improve services to farmers through plant clinics. Potentially, these clinics could grow into one-stop shops by widening the portfolio of advice and information to include, for example, soil fertility management, choice of varieties, seed quality, postharvest management, nutritional value of bio-fortified foods, and even animal nutrition and health. By involving service providers with complementary skills and by playing a stronger role in linking farmers to agro-vets, microcredit schemes and markets, the attractiveness for farmers of regularly visiting the clinics is likely to increase substantially.

Plant clinic records

The registration of farmer queries for monitoring and progress tracking has received a great deal of attention by the implementing institutions because the data can be used to assess and improve the overall clinic functioning. The fact that logbook data showed a higher number of queries per session (40% higher than POMS) and POMS data a higher number of clinic sessions (26% higher than the logbooks) indicate that both records under-report on plant clinic activities (). Overall, the Rwandan POMS data seem to under-report by at least 40–50%. Although neither POMS nor logbook data were fully complete and accurate, both datasets showed similar overall attendance patterns (), thus confirming our initial assumption that there are substantial differences in farmer attendance among Rwandan plant clinics.

There were several reasons for the inaccuracies and inconsistencies between POMS and logbook data: the prescription form is not filled for every query if several farmers present the same problem; the filling of the form is perceived as time consuming and therefore not always done; POMS and logbook data are reported to the programme coordination on different dates; there is a lag period from when the prescription form is filled in to when the data are uploaded to POMS; some prescription forms are rejected due to incorrect filling; and sometimes the plant doctors forget to fill the logbook. In Kenya, the change from paper prescription forms to tablets has greatly improved data accuracy and completeness (Wright et al. Citation2016). It was beyond the scope of this study to assess this aspect.

The procedures for managing plant clinic data need to be reviewed in order to create a leaner and more practical system that allows for accurate recording of clinic attendance. The current under-reporting can potentially undermine policy buy-in to the plant clinics on the grounds that they are not efficient or cost-effective enough. The existing practices are time consuming and the two systems are not properly aligned. POMS is a key source of information to track farmer attendance, monitor plant doctor performance and inform relevant stakeholders about patterns of pests and diseases (Finegold et al. Citation2014). POMS-based data management training is therefore an important part of the plant health system strengthening efforts of the Plantwise programme. In contrast, the logbooks have a more informal status and have therefore not received the same attention as POMS. Rwanda is one of the few Plantwise countries to consistently use logbooks to record clinic activity. More attention should be paid to the potential role of logbooks as a complementary source of clinic information for managers and decision-makers.

Conclusion

This exploratory study has brought new insights into the operations of Rwandan plant clinics and why some appear to have consistently lower or higher farmer turnout than others, despite fairly similar basic conditions in terms of staffing, funding, and logistics across districts. Personal and organisational commitment combined with good publicity and proactive communication with the farmers and local leaders stood out as important determinants of higher attendance. Despite the staff and funding restrictions faced by all districts, the high-attendance clinics seem to have created a virtuous circle of motivation and accountability, reflecting both on the individuals and the institutions. Other factors not addressed in this study are likely also to influence farmer attendance, such as distance from the farmers’ home to the clinic, crops grown, purpose of growing, and socio-economic status of farmers.

Overall, there is room for improvement of the plant clinic operations. Women are under-represented at both low- and high-attendance clinics. Access to affordable quality inputs and effective measures against the big, rampant diseases remain major challenges for the plant clinics. Although the systems for managing plant clinic data are relative well-functioning in Rwanda compared to other countries, they did not give the full picture of the plant clinics’ activities and tended to under-report farmer attendance. This is a risk to the perceived value of plant clinics. Improvements are required in order to make clinic records reliable tools for managers and policymakers at both district and central levels.

The agricultural extension policy in Rwanda provides a highly conducive environment for integrating plant clinics into the diverse extension landscape and exploring the potential synergies and complementary functions of plant clinics, FFS, and farmer-to-farmer extension. There is an unexplored potential in widening the services that can be provided through the plant clinics. In order to create a solid institutional base for this, local governments need to formally embed the plant clinics into the districts’ work routines and budgets.

This article provides new details around the human and organisational complexities of plant clinic operations. We conclude that such assessments can help improve the realisation of the clinics’ potential in a given context.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participating plant doctors, farmers, and plant clinic coordinators for providing insightful information and views on plant clinic operations for the study. Thanks to Dannie Romney for constructive comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Jean Claude Noel Majuga holds a Masters in plant sciences, with a specialisation in natural resources management, from Wageningen University, The Netherlands. He has a Bachelor’s degree in horticulture.

Bellancile Uzayisenga is a researcher working for the Rwanda Agriculture Board. Her key research interest is plant biosecurity. She holds an MSc in plant sciences with a specialisation in a plant pathology and entomology, from Wageningen University, The Netherlands and has 10 years’ experience working with crop protection research and extension. She is the National Coordinator of Plantwise in Rwanda.

Jean Pierre Kalisa is Plantwise Officer at RAB and a plant doctor trainer. He holds a Masters of advanced studies in integrated crop management from the University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. He has 12 years’ experience working in different aspects of agriculture extension. Before joining Plantwise in 2013 he was a coordinator of the Crop Intensification Program (CIP) in Southern province.

Conny Almekinders is an Associated Professor in the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation group at Wageningen University. With a background and PhD in the plant sciences, she now focuses on interdisciplinary research and socio-technical interaction in the field of agricultural and rural development.

Solveig Danielsen is Research Coordinator of Plantwise, CABI. She holds a PhD in plant pathology from the University of Copenhagen. She has 20 years of experience working in plant health, agricultural research and extension, policies and institutions in developing countries. Before joining CABI in 2012 she was an Associate Professor at the Centre for Health Research and Development, University of Copenhagen.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 CABI’s global Plantwise programme aims to contribute to improved food security and rural livelihoods by promoting networks of plant clinics, improving the management and use of plant health data and strengthening the links between key actors in plant health. It operates in 34 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Plantwise replaced the Global Plant Clinic, a former CABI-led initiative, in 2011.

2 POMS accessed 01.05.2017.

3 US$1 = 810 Rwandese francs (RWF).

References

- Boa, E. 2009. “How the Global Plant Clinic Began.” Outlooks on Pest Management 20: 112–116. doi: 10.1564/20jun05

- Brubaker, J., S. Danielsen, M. Olupot, D. Romney, and N. Ochatum. 2013. “Impact Evaluation of Plant Clinics: Teso, Uganda.” CABI Working Paper 6. Wallingford: CABI.

- Danielsen, S., J. Centeno, J. López, L. Lezama, G. Varela, P. Castillo, C. Narváez, I. Zeledón, F. Pavón, and E. Boa. 2013. “Innovations in Plant Health Services in Nicaragua: From Grassroots Experiment to a Systems Approach.” Journal of International Development 25 (7): 968–986. doi: 10.1002/jid.1786

- Danielsen, S., and F.B. Matsiko. 2016. “Using a Plant Health System Framework to Assess Plant Clinic Performance in Uganda.” Food Security 8 (2): 345–359. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0546-6

- Danielsen, S., F.B. Matsiko, and A.M. Kjær. 2014. “Implementing Plant Clinics in the Maelstrom of Policy Reform in Uganda.” Food Security 6 (6): 807–818. doi: 10.1007/s12571-014-0388-7

- Finegold, C., M. Oronje, M. Leach, T. Karanja, F. Chege, and S. Hobbs. 2014. “Plantwise Knowledge Bank: Building Sustainable Data and Information Processes to Support Plant Clinics in Kenya.” Agriculture Information Worldwide 6: 96–101.

- Hirschfeld, M., T. Davis, and B. Ezeomah. 2016. “Plantwise Evidence of Impact.” Plantwise summary report. Wallingford: CABI.

- Kilalo, D., F. Olubayo, and F. Toroitich. 2014. “Analysis of the Process of Plant Clinics: A Case Study for Kenya.” Plantwise study report. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

- Mahr, D.L., P. Whitaker, and N. Ridgway. 2008. Biological Control of Insects and Mites: An Introduction to Beneficial Natural Enemies and their Use in Pest Management. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Mandula, B., T. Mayani, A. Chikomola, and F. Kayuni. 2016. Farmer Participation in Plant Clinics in Malawi. Lilongwe: Ministry of Agriculture of Malawi and Self-Help Africa.

- MINAGRI. 2009. National Agricultural Extension Strategy. Kigali: Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources, Rwanda

- Mur, R., F. Williams, S. Danielsen, A.G. Belanger, and J. Mulema, eds. 2015. “Listening to the Silent Patient. Uganda’s Journey Towards Institutionalizing Inclusive Plant Health Services.” CABI Working Paper 7. Wallingford: CABI.

- Nsabimana, J.D., B. Uzayisenga, and J.P. Kalisa. 2015. “Learning from Plant Health Clinics in Rwanda.” Plantwise-CABI. Kigali: Rwanda Agriculture Board.

- Plantwise. 2015. Plantwise Strategy 2015–2020. Wallingford: CABI.

- RAB. 2014. Plantwise Initiative in Rwanda. Annual Report. Kigali: Rwanda Agriculture Board.

- Silvestri, S., and R. Musebe. 2016. “Participatory Assessment of Farm Level Outcomes and Impact of Crops Pests and Diseases Management.” Plantwise study report. Nairobi: CABI.

- Vurro, M., B. Bonciani, and G. Vannacci. 2010. “Emerging Infectious Diseases of Crop Plants in Developing Countries: Impact on Agriculture and Socio-economic Consequences.” Food Security 2 (2): 113–132. doi: 10.1007/s12571-010-0062-7

- Wennink, B., and R. Mur. 2016. “Capitalization of the Experiences with and the Results of the Twigire Muhinzi Agricultural Extension Model in Rwanda.” Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute.

- Wright, H.J., W. Ochilo, A. Pearson, C. Finegold, M. Oronje, J. Wanjohi, R. Kamau, T. Holmes, and A. Rumsey. 2016. “Using ICT to Strengthen Agricultural Extension Systems for Plant Health.” Journal of Agricultural & Food Information 17 (1): 23–36. doi: 10.1080/10496505.2015.1120214