ABSTRACT

Parivartan Plus is a structured sports mentoring programme for girls, implemented in a Mumbai slum where social expectations around gender-appropriate behaviour and good parenting restricts girls’ mobility and visibility in public spaces. This article presents practice-based learning from developing and implementing programme theory to empower girls in achieving changes in their everyday social interactions at home and beyond. Gender and social norms theory were combined with local practical wisdom to turn main implementation challenges into opportunities. The article reflects on the strategies that gave visibility to, and achieved community endorsement for, the erosion of restrictive gender norms while ensuring community safety.

Introduction

Gender equality is both a goal in itself, and a means to achieve a wide range of health and development outcomes (United Nations Citation2015). Global evidence shows that – across social and geographical settings – unequal gender norms are harmful to adolescent girls’ development and freedoms (John et al. Citation2017). In India, mobility restrictions limit girls’ access to formal education and economic opportunities and thus lead to early marriage (Phadke Citation2007). Various programmes exist that address gender norms with several integrating sports components (John et al. Citation2017). The integration of sports activities is partly explained by the recent surge of “sport for development” programmes in lower and middle-income countries, promoted by both local and international agencies. Since 2001, for instance, the United Nations Office on Sport for Development and Peace (UNOSDP) began to coordinate efforts to promote the role of sport and physical activity in international development, education and public health (Hayhurst Citation2013; Kidd Citation2008). The Declaration of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes sport as an important enabler of sustainable development, highlighting its role in promoting tolerance and respect that contribute to the empowerment of women, young people, and communities (United Nations Citation2015). Participation in sport leads to physical well-being and comes with many health and other benefits for the individual: developing life skills, building self-esteem, strengthening self-efficacy, improving motivation and encouraging personal responsibility (Srivastava and Sumrani Citation2012).

Donors and corporate social responsibility programmes share great enthusiasm for sports programmes; yet some critics have started questioning the often exaggerated claims about the developmental powers of sport (Guest Citation2013; Kidd Citation2008). Particularly in gender programmes, the onus is put on girls to act as “new agents” of social change, overlooking the broader structural inequalities and gender relations that marginalise girls in the first place (Hayhurst Citation2013). Little is known about how sport can reframe the unequal gender norms that are critical obstacles to gender equality (Hayhurst Citation2013). Indeed, economic and socio-political realities, as well as gendered expectations within the family and community, constrain girls’ agency and ability to change. That girls even have the option to participate in sports programmes cannot be assumed (Guest Citation2013; Hayhurst Citation2013) which calls for attention to more inter-cultural sensitivity in development programming (Coalter and Taylor Citation2010; Kidd Citation2008). To transform gender norms, change strategies must be implemented at the individual, family and community level (Dworkin, Fleming, and Colvin Citation2015) based on robust theories of change (Jewkes, Flood, and Lang Citation2015).

This article aims to extract practice-based insights from developing and implementing a culturally-sensitive gender transformative sports programme. We describe in more detail how we designed the programme theory, applying cutting-edge knowledge in gender programming while ensuring inter-cultural sensitivity in implementation. We then reflect on the main implementation challenges and how they turned into opportunities, ultimately contributing to achieving norm shifts. We end by highlighting particularly effective programme strategies, concluding with reflections on the importance of “staging” change in gender transformative programming.

Parivartan for girls

STRIVE, a research consortium on the structural drivers of HIV, investigates what programmes work to tackle social norms that underpin gender inequality. It sponsored “Parivartan for Girls”, a sports and mentoring programme designed to increase adolescent girls’ self-esteem, self-confidence and educational aspirations while addressing entrenched norms against women’s use of public space. The idea was first inspired by “Parivartan for Boys”, which was designed to promote gender-equitable attitudes among adolescent boys by engaging cricket coaches to serve as role models for healthy masculinity. It was developed jointly by the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW) and Apnalaya, a local NGO with deep roots in the Mumbai slum community where it was piloted (Miller et al. Citation2015). The collaboration between ICRW and Apnalaya, and Apnalaya's long-standing relationship with the local community provided an ideal context to pilot and explore the viability of a girl-focused sports programme. The adaptation for girls required a radical rethink of the programme design: there were no local female role models for girls in sports and playing sports requires girls to be active in ways generally considered socially inappropriate. This research and demonstration project was designed to determine whether a female-focused Parivartan programme could empower young girls and erode dominant norms that question the appropriateness of adolescent girls inhabiting public spaces and prioritising their health and wellbeing over household responsibilities.

At the design stage, we used participatory research with community members to operationalise all components of the intervention and test assumptions. We used problem trees and safety mapping with eight groups of girls, five groups of mothers and four groups of fathers to explore local beliefs. These revealed that restrictions on girl’s ability to play or aspire to sports relate back to her future marriageability and that the gendered division of labour – with women’s primary responsibility to look after the family, children and in-laws – keeps girls at home. This itself plays into beliefs that they lack the abilities to play sport as it is seen as an activity for boys. Parents expressed concerns about sports-related injury affecting the girls’ marriageability. With a girl seen as somebody else’s property (paraya dhan), good parenting implies handing her over at marriage without any blemishes. The perceived threat of sexual harassment in public spaces, with potential reputational damage, was the main barrier, both for leisure and for attending school. Girls’ presence in public spaces could easily evoke potential opposition from both parents and community members given the strong community norm that good parenting meant protecting girls from the male gaze – an expectation closely policed by relatives and neighbours. The dominant gender system creates a culture of impunity for boys who behave disrespectfully toward girls, with community blame targeted at the girls and parents instead (John et al. Citation2017). While some development practitioners recommend involving men, boys, women and girls simultaneously in change processes (John et al. Citation2017), we intentionally chose not to engage men and boys in evaluating whether a girl-centric approach to change is viable in this setting. At this stage, the most important interpersonal contacts for girls are in fact with their parents who are sanctioned when she is seen not to comply with societal values of good feminine conduct. We hypothesised that change in gender norms might begin by changing what girls and parents believed others in their surroundings would say if they saw a family’s girl out and about.

We held discussions with parents, girls, and community stakeholders to identify the most appropriate sport for the project. The choice fell on “kabaddi”, a contact team sport that requires no equipment and only limited resources and space, both critical factors in a resource-deprived, crowded slum. At the programme’s core were ten mentors, selected from gender-progressive families within the slum. They participated in intensive gender training and then guided teams of 12 to 16-year-old girls through a structured programme of sport and life education, running over a period of 15 months. The mentors helped girls develop awareness of their potential by improving their physical fitness and increase self-confidence by facilitating participatory discussions on a variety of topics, ranging from life skills and health to gender, violence and sexual harassment. The programme aimed to support girls’ activities in the family and the larger community. Family engagement was achieved through the formation of parent reflection groups, while community endorsement was sought through involving key community stakeholders into attending girls’ public kabaddi events and tournaments.

During implementation, we adopted a prospective design of qualitative case studies with ten mentors and 15 athletes, each interviewed at three time points, including a year after the end of the programme. Semi-structured interviews were recorded, transcribed and translated verbatim, and we combined thematic and narrative analyses, with more details provided elsewhere (Bankar et al. Citation2018). These case studies allowed the study of subtle changes in day-to-day social interactions and negotiations as well as the sustained changes in aspirations, gender attitudes and perceived shifts in gender norms among reference networks, defined as all people whose expectations matter to the individual in a particular context. Monitoring data included attendance registers, field notes from trainers and staff on meetings with parents, and minutes of monthly meetings with mentors to discuss challenges encountered and changes initiated or adaptations made during the sessions.

The processes of change observed among mentor and athletes are written up in more detail elsewhere (Bankar et al. Citation2018; Cislaghi et al. forthcoming). Briefly, the case studies demonstrate how mentors contested mobility restrictions by taking risks as a group first, with collective agency an important step towards greater individual agency in day-to-day social interactions. Parivartan helped them negotiate a “respectable” identity, sidestepping reputational risk such that their presence in public spaces became de-sexualised. More assertive communication was central to the change processes. Demonstrating greater negotiation skills within the family helped athletes and mentors win parents’ trust in their ability to be safe in public spaces. Parents became active players: their aspirations for their daughters changed. As daughters negotiated increased freedoms, mothers were strategically important in changing dynamics at home. This was reinforced by contact with mentors who modelled a culturally appropriate “alternative” young woman who was more educated and was not yet married by the age of 20. Both girls and parents started to resist the social sanctions from neighbours and relatives. The programme achieved endorsement at the community level for eroding dominant gender norms while ensuring the safety of girls. While results are reported elsewhere, in this paper, we focus specifically on offering findings to other practitioners who might be interested in adapting and implementing the Partivartan Plus intervention.

Designing a theory of change based on theory and local context

Parivartan’s theory of change (ToC) was informed by theory, formative research and grounded knowledge of the community. The underlying assumption was that by participating in sports, girls would increase their confidence and self-esteem. By aspiring to a collective goal, they will learn negotiation skills and teamwork, and become more powerful to claim space as a group. These competencies will transfer into their individual lives and ultimately translate into continued education and delayed marriage. The main barriers identified in the ToC were those related to social expectation around gender-appropriate behaviour and good parenting as explored through the formative research.

We drew on both social norms theory and gender theory. Social norms theory (Cislaghi and Heise Citation2018; Morris et al. Citation2015) posits that beliefs about social expectations strongly influence behaviour. Individuals’ actions are understood as a function of a setting’s existing system of beliefs and expectations that intersects with individuals’ attitudes and agency. A distinction is made between descriptive norms (one’s beliefs about the behaviour of others) and injunctive norms (one’s beliefs about what others approve and disapprove of) (Goldstein and Cialdini Citation2007). Gender performance theories draw attention to the symbolic aspects and visible display of gender. By “doing” or performing gender, individuals systematically reproduce socially constructed differences between women and men (John et al. Citation2017; Ridgeway Citation2009). Relational theories of gender (Connell Citation2012) see gender as a multidimensional structure operating in a complex network of institutions. Gender relations are contained, created, and constructed, and the everyday practices of individuals are shaped by gendered power relations. The practical implications of these theories for programme design were that attention must be paid to facilitating shifts in cognition and behaviour of girls, and to making that change visible. It informed our focus on bringing about subtle and gradual changes in the day-to-day social interactions of girls at home and in the community. When vanguard girls and young women within a local community start behaving differently in visible ways, change becomes more accessible for the other girls. Increasing visibility of girls in public spaces and relaxing mobility restrictions was both considered essential and an anticipated challenge. Girls’ restricted access to public space evolves from socially produced fear: when girls transgress social restrictions, it brings shame upon the entire family (Paul Citation2011; Phadke Citation2007). Girl’s presence in public spaces invites social sanction as parents are seen as incapable of providing a good upbringing (Phadke Citation2007). Empowering girls thus requires not just increasing their capacity to resist social expectations but also changing the expectations that parents and the community put on them. At a practical level, this demonstrated the importance of engaging parents in supporting their daughters and of fostering community openness to girls’ asserting more agency.

The partnership between ICRW, an international organisation at the cutting edge of gender programming, and Apnalaya was integral to the programme. The local NGO’s in-depth knowledge of the community significantly assisted the mentor-based role model strategy. Apnalaya was able to identify “positive deviant” families previously engaged in their development and educational initiatives, facilitating the recruitment of suitable young, educated women aged 18–24. They received intensive training in gender and sports coaching to become mentors and local role models the community could easily relate to. Ten mentors guided teams of athletes through a structured programme running over a period of 15 months.Footnote1 Girls met twice a week: once for two hours to play kabaddi at the sports ground on Sundays, and once for one and a half hours of reflection sessions mid-week at a local Apnalaya centre. The gender curriculum alternated card series session with group education activities (GEA). The card series introduced topics on life skills, for example, dealing with emotions, goal setting, dealing with peer pressure, enhancing self-esteem; gender equality, gender roles and discrimination regarding schooling and mobility; and healthy habits for adolescents. This involved a better understanding of puberty and how to respond to instances of sexual harassment, or other forms of violence girls may face in the community. Topics introduced and discussed in one week were reflected on through role play and games in the group education sessions the next week. Mentors facilitated all sessions except for one. To avoid all possibility of misinformation, a female doctor stepped in on the topic of menstruation and bodily changes during puberty. The expected outputs included a cadre of 10 mentors trained in gender and sports, and 100 girls finishing the structured curriculum.

Proactive family engagement was promoted with the formation of parents’ groups. For the duration of the programme, monthly reflection group sessions were planned with both mothers and fathers of participating girls, facilitated by Apnalaya staff. These discussion sessions covered communication skills between parents and daughters, the value of girls and girls’ education, benefits of delaying marriage and issues around sexual harassment. The expected outputs included the exposure of parents of at least 100 girls to gender-sensitisation with 10 to 15 fathers mobilised to speak out in favour of girl’s education, participation in sports and enhanced mobility. The parents and girls were to form a new reference group or network, getting visibility within the community for resisting the social pressure of prevailing gender norms and opting for more gender progressive ones.

A Community Advisory Board was established to ensure buy-in, gain advice and feedback on all proposed activities from all critical stakeholders. The advisory board included members of Mahila Mandals (Women's Federation), youth groups, NGOs and CBOs working on the issue of women and girls, religious and political leaders, school representatives, higher educational institutions working on social work and counselling, police and BMC (municipal corporation). Ongoing interactions with stakeholders during the implementation stage further guided adaptations to overcome local barriers. Community ownership was sought throughout, with parents, girls, and community stakeholders all choosing kabaddi as the preferred sport. Girls playing kabaddi in public spaces was perceived out-of-bounds, and community members insisted that the sports sessions be organised in a school ground closed off by a boundary wall, with a security guard present to ward off the gaze and unwanted attention of boys and men. A tournament was planned towards the end of the programme to foster community endorsement and create visibility of girls involved in sports.

We now move onto reflecting on the main challenges during implementation of this carefully structured programme.

Reflecting on implementation challenges

Recruiting and retaining participants into a kabaddi programme

Recruiting the required number of athletes for ten kabaddi teams took much longer than anticipated: a total of 450 eligible families were approached to obtain consent for 150 girls to participate. It is at this stage that mentors started engaging intensively with parents of athletes. They visited them several times to complete consent procedures for participation in the programme. When fathers were frequently absent during these visits, their consent was bypassed when mothers were happy to sign the consent forms.

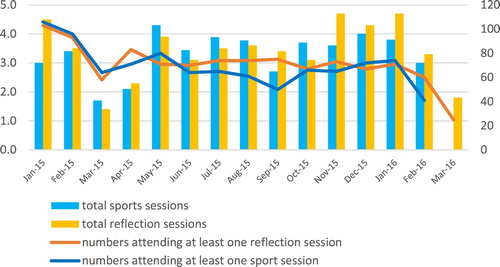

The programme started at the end of December with 35 out of the 150 girls never attending a single session. presents the average number of kabaddi and reflection sessions held by mentors and the number of girls who attended at least one session each month. There was a considerable drop off in the first couple of months, and by February a third of those recruited had dropped out. Various reasons explain this early dropout with the main two being: the ambivalence of the girls (not all girls had an aptitude for, or interest in, sports) and reluctance among parents. Some parents withdrew their support once they realised that participation required a long walk (45 minutes to one hour through the community) to the sports ground. Parent's initial concerns about kabaddi injuries affecting the girls’ marriageability did not have a significant impact on attendance or cessation. There were six instances of injury over the 15 months, with the two more serious ones that needed medical attention leading to the permanent withdrawal from the sports sessions.

Figure 1. Average number of kabaddi and reflection sessions, and number of girls who attended at least one session per month.

In March, fewer sessions were held, and attendance dropped because of exams, but it picked up afterwards. During the rainy season, the sports sessions had to happen indoors for three months from June and attendance dropped further in September. The programme team therefor scheduled a mini-tournament in October at the usual school ground with parents invited to attend to reignite interest and support. About 30 mothers and one father came to see their daughters compete.

Logistical challenges coordinating the use of sports grounds and availability of mentors

All ten teams needed to share the school ground on Sundays with groups accommodated over three time slots. Four groups (two junior groups, age 12–14 and two senior groups, age 15–16) shared the morning slot from 11 am to 1 pm; two junior groups used the ground from 2 to 4 pm, and two junior and two senior groups shared the late afternoon slot (4–6 pm). The complicated logistics of limited time and space turned into an advantage at times that mentors were absent due to illness or family commitments. Other mentors stepped in with teams adjusting and giving athletes the opportunity to interact more closely with other mentors and role models. Similarly, some girls switched to a different kabaddi team midway through when timings clashed with new academic commitments or other regular engagements. Girls and their parents came to know a pool of mentors, each one having a unique background, personality, and a range of aspirations.

Two mentors discontinued their engagement with Parivartan on the demand of future in-laws as marriage negotiations were in progress (Bankar et al. Citation2018). When the first mentor dropped out in July 2015, another mentor who lived in the same area took over her group of athletes. As they had coordinated visiting families together during the recruitment, there was sufficient rapport with the parents of the athletes. A similar arrangement was not possible for the second mentor who dropped out in November 2015. While initially the other mentors took turns running the reflection and sports sessions this proved untenable, and the team dissolved. Some athletes joined other teams, but six athletes discontinued, disgruntled with loss of rapport with a single mentor.

Engaging fathers

The formative research predicted difficulties with organising reflection groups with fathers given both time constraints and gendered expectations around parental responsibilities. A review of parenting interventions (Panter-Brick et al. Citation2014) shows that the gendered nature of family functioning and community action perpetuates gender biases in programme design by focussing uniquely on mothers. Our experience (partly) illustrated this point in the first group session covering the understanding of young girls’ dreams, desires and aspirations. Fathers confessed ignorance and said it was not a topic routinely discussed within the family or community: “I don’t know … her mother must be knowing”, “I don’t talk to my daughter much” and “these are not the things that we discuss at home”. A few men could not conceive that girls’ aspirations might go beyond doing household chores and childcare. This confirmed that matters regarding education and upbringing of children was considered the remit of mothers, while fathers saw it as their responsibility to participate in community initiatives on housing, electricity, and other civil matters. Poor attendance during this first session precluded continuation and the Parivartan group sessions with fathers.

Men unwilling or unable to attend father groups is not unique to our context, yet care should be taken not to marginalise them even further by programme evaluations neglecting to report on father participation and impact (Panter-Brick et al. Citation2014). Most interventions engaging men have focussed on HIV prevention, reproductive health and addressing gender-based violence (McAllister et al. Citation2012). Evidence from parenting programmes involving fathers is mainly from the Global North, targeted at young children (< 8years) or children at risk of maltreatment (Panter-Brick et al. Citation2014). With responsibility for childcare so central to gender inequality, there is little evidence on engaging men as fathers and caregivers in the global South (McAllister et al. Citation2012). One intervention in Turkey, also a patriarchal and sex-segregated society, encouraged fathers to go beyond the role of breadwinner and disciplinarians. Promoting reflection on childhood experiences of relating to their dads was a successful entry to exploring more open emotional expression in their family relationships. (Barker, Doğruöz, and Rogow Citation2009).

The Parivartan messages reached fathers at home, primarily through mothers though increasingly through daughters themselves. In retrospect, home was a safer context for men to observe and undergo gradual change; a group setting might have evoked posturing against change. Most men lent their tacit support by approving their wives’ involvement, leading us to reflect on how patriarchy operates when men may support change without wanting to be seen as advocates for gender transformation. It raises an important question about how far to go in seeking father’s support as a “culturally appropriate” strategy or whether there are subtler trajectories in transforming fathers. We tried to engage fathers but did not go the full length, even sometimes bypassing them by taking consent from mothers. Thus initially many fathers did not know the full details of Parivartan, particularly that it had a sports component. Some mothers had deliberately not told their husbands, which in some cases did lead to the daughter’s withdrawal when the father found out. Once beyond the first couple of months, only three or four girls had to drop out because of a father’s objection. The timing seemed relevant as quite a few fathers came to realise that their daughters played kabaddi at the time of the public tournament towards the end of the programme. This did not lead to a backlash, but instead, fathers accepted girls’ engagement in sports with a sense of pride as they witnessed their daughters’ perform in public. Gender dynamics within families did change and increasing girls’ and women’s agency within, rather than against, the institutions of family and community avoids adverse consequences (Khurshid Citation2015).

Reinforcing effective strategies

In this section, we highlight the strategies we found particularly compelling and thus worth advocating for in other sports-for-development programmes, or programmes addressing gender.

Combining sports with a curriculum on gender

Sport as a vehicle for a gender transformative programmes was beneficial and valuable as girls playing sports challenged gender norms in and of itself. But sports sessions on their own are not sufficient; instead, they need combining with a well-structured curriculum of reflection sessions including gender expectations, myths, bodily autonomy and rights. The awareness gained through reflecting on ideas in this curriculum ultimately led to changes in beliefs and expectations that then needed to be put into practice with peers, at home and in the wider community. The ideas and concepts taught in the reflection sessions on negotiation, agency and rights complemented the skills gained from playing a team sport. The sports ground was a safe place to practice different ways of being and dressing. The athletes received a sports outfit (track pants and jersey), but given the prevailing culture of shaming women's bodies, nobody was forced to wear it against their comfort level or their parents’ objections. Many remained in salwar kameez the first couple of weeks and changes were gradual, while others changed into the outfit at the ground. Once a few girls started wearing the sports outfit, others saw how inconvenient the salwar kameez was for playing kabaddi. While physical exercise and playing sport helped develop girls’ sense of ownership over their bodies, the discussion sessions on “knowing the body” made girls reflect on myths and restrictions and helped them deal with feelings of shame and discomfort.

Changes went beyond the sports ground as within a few months many walked to the ground dressed in their sports attire, while a minority stayed in burkha until they reached the school ground. Not surprisingly this invited comments from neighbours and name-calling by men and boys. Mentors and athletes navigated this social disapproval with an increased level of confidence, emboldened by the safety of the group. The initial inconvenience of the long walk to the sports ground provided the opportunity to spend more time together and develop friendships and to cultivate collective agency and practice in challenging men or boys on the way. Social interactions in public spaces changed gradually and became quite central to girls and women feeling safer in public spaces. This change process was not straightforward and depended heavily on the mentors’ growth process and the ways they strategised to keep safe and build confidence (Bankar et al. Citation2018). Collective agency in taking risks and claiming space as a group has been shown an important step towards greater individual agency (Bankar et al. Citation2018; Kippax et al. Citation2013). With this gradual and strategic approach, there were no reports of serious incidents or adverse consequences. Instead, it gave clear visibility to the introduction of alternative ways of dressing and moving through the community for young women and girls.

Engaging mothers to facilitate changes at home

The direct engagement with mothers during reflection groups kept mothers from feeling excluded from their daughters’ process of transformation. When it came to the topic of understanding girls’ dreams, desires and aspirations, mothers became emotional. They acknowledged their daughter's educational and career aspirations and reflected on how their own hopes had been crushed by societal expectations and poverty. Anticipating that their daughters’ future might replicate their own, ultimately inspired their desire for change, providing a solid base and opening for alternative ways of thinking and acting.

While these group sessions were important opportunities for mothers to reflect, ultimately it was the athletes initiating change at home that catalysed change. The home was the next “practising ground” for more assertive communication. At every stage, athletes were encouraged to share ideas and reflections at home to engage parents. Mothers and sisters were often captive audiences, curious about the new concepts covered during the reflection sessions. Mothers were initially and conventionally the ones to strategically negotiate with their husbands, yet both parents started to be more open to the athlete daughter’s views. Sharing was helpful in endorsing aspirations and accepting changes in her way of communicating: whether it was asking permission to do something, or participating in discussions she would not have done previously. The mere fact that many athletes started communicating with fathers and elder brothers was evidence of subtle changes in day-to-day relating within the family. The frequent interactions of the parents with the mentors as acceptable role models made a powerful contribution to this change process at home (Bankar et al. Citation2018).

Mentor-based approach building role models within the community

As young women from the slum community, mentors were best placed to “translate” new ideas to parents and practising new skills gained during their intensive gender training. Initially, interactions focused on persuading parents to let their daughters participate. The selection process of mentors started in August 2014 and came with its own initial challenges (Bankar et al. Citation2018). The official programme launch happened in November 2014 when mentors had gone through two sets of training, enabling them to stage and anchor the entire event. Mentors had done group formation sessions with their teams and each team “performed” either a dance or a song on stage in front of an audience consisting of parents and key stakeholders (though not the wider community). This inspired trust and demonstrated endorsement by respected community members.

Once the programme started, mentors collected athletes at their homes to walk to the sports ground together, and informal chats provided another opportunity for the gender curriculum to reach parents. Regular contact with “positive deviant” young women regarding educational aspirations and achievements reinforced what was possible in the community. Mentors reflected on relationships of trust building, with parents actively seeking advice on their daughters’ education. Hence mentors had become integral parts of the reference groups of both the athletes as well as their parents.

Throughout the programme, the mentors were strong role models for the athletes and gained respect from parents and neighbours for providing a community service. They were increasingly seen as leaders through their increased networking. Going beyond the expectations of the programme three mentors were nominated to a community vigilance group, a committee within the Shivajinagar police station designed to help ensure a safer community for all. They thus became responsible for reporting any crime or violence that occurs in their neighbourhood to the police. Many women in the community feel reluctant or do not know how to report violence. Anticipated safety concerns about girls in public spaces were alleviated not just for the girls and their parents: Parivartan seems to have facilitated positive social connections leading to greater community safety.

Enhancing visibility of change: public tournaments for community endorsement

While the programme launch was not open to the wider community, the kabaddi tournament planned towards the end of the programme was. As influential community leaders, the members of the advisory board actively encouraged community members to attend the tournament in January 2016, as girls competed in public in front of big audiences of mainly men and boys. It was a public declaration to the community that girls can and do play sport, and moreover that parents within the slum allowed their daughters to do so. Several fathers openly cheered their athlete daughters and made public declarations to support their daughter’s education. The tournament was also a platform for mentors to take stands on the girl’s empowerment in front of a big audience and foster community endorsement for Parivartan. Parents who had initially refused for their daughters to join the programme expressed the desire to enrol their daughters after the tournament.

Given its success in enhancing the visibility of change, it was decided that the best graduation ceremony would involve another public tournament, held nine months after the programme ended. Athletes who had dropped out now turned up to play and be seen to graduate from the sports programme, a total of 96 girls. Future programmes could consider staging these public tournaments earlier and more often.

The community endorsement for Parivartan eroding dominant norms was a significant achievement with the reputation of the local implementing partner instrumental in providing credibility to this new initiative. With a relationship of trust built over 40 years of community development, Apnalaya could gauge the extent of risk that was acceptable. Parents were often willing to consider their daughter's continued participation because Apnalaya supported it, which has implications for scale-up. Stakeholders interested in far-reaching and sustained changes, including governments and international donors have the responsibility to support local organisations that are truly embedded in the community and can help transform norms through its convening abilities. While social theory and international expertise in gender-programming were critical, the expert judgement by Apnalaya and the strategies developed by the mentors should be fully acknowledged, credited and made transparent. National and state governments in India need to provide spaces for credible civil society engagement and help deepen their presence in the communities, rather than continuing top-down development programmes.

Conclusion

The successful implementation of Parivartan for girls suggests that it is possible to effectively implement a sports-based programme in a slum community where girls have no role models, no aspirations for careers and no sense of collective power. We did not overlook the structural inequalities that marginalise girls but instead paid full attention by engaging with all levels of the social ecology in the programme theory. In particular, we understood that in contexts where individual agency is largely constrained, social change starts at the level of day-to-day social relations that individuals and groups cultivate (Kippax et al. Citation2013). Gender-relational and gender performance theory helped us focus on gradual and subtle changes in daily social interactions by mentors and athletes claiming space in their neighbourhoods and the community. Charting out a comprehensive strategy to support young women and girls to contest restrictive norms, it is possible to set in motion the creation of new norms encouraging girls’ agency, development and well-being. Besides a comprehensive ToC, we needed the flexibility to deal with ground realities by keeping our focus on the end goal increasing aspirations for education and delayed marriage.

Many of the initial obstacles to the implementation proved to be opportunities. At the start, not all parents could be convinced to go against the norms and let their daughters participate in a sports programme. Indeed, only one-third of families with eligible girls gave consent, and we did not anticipate a near 50% drop out by the end. In contrast, participating girls changed impressively and affected change in their families, indicating that we need to “stage change”. Rather than putting energy in convincing reluctant families to join, we need to work with families most ready for change. Social norms theory encouraged us to create, develop and expand reference groups that grew from the most gender-progressive families within the slum, and to foster community endorsement through promoting visibility of girls and families aspiring to better education and growth opportunities for daughters. This can then effectively instigate a desire for change in others, witnessing realistic alternatives within the community.

By fostering community ownership and accountability, Parivartan has facilitated the creation of new positive social connections within the community which seems to have led to more community safety. Not just through the nomination of mentors on the community vigilance group, but by creating a sense of safety among participating girls as they practised challenging unwanted attention from men and boys and rebuke harassment as they walked through public space without demeaning consequences. While sport was an excellent vehicle for gender-transformation, not all girls had the aptitude or interest to play kabaddi. In the future, we may need to supplement it with other leisure alternatives to maximise the potential of challenging gender norms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deep gratitude to all the mentors and girls on the Parivartan programme. Without their enthusiasm and participation, we could not have undertaken the programmes and research. We would also like to express our gratitude to Mr. Arun Kumar and Ms. Rama Shyam and others on the Apnalaya team who worked closely with us on Parivartan Plus.

We are very grateful to the Department for International Development (UKaid) for funding the STRIVE research consortium on tackling the structural drivers of HIV/AIDS, for making this collaboration possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Martine Collumbien is an Associate Professor in Sexual and Reproductive Health Research, Faculty of Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

Madhumita Das is the Director, Program and Innovation at CREA, New Delhi, India.

Shweta Bankar is a Technical Specialist at International Centre for Research on Women, Mumbai, India.

Beniamino Cislaghi is an Assistant Professor in Social Norms at the Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

Lori Heise is Visiting Professor at the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, US.

Ravi Verma is the Regional Director at the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) Asia Regional Office in New Delhi, India.

ORCID

Beniamino Cislaghi http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6296-4644

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Details on the programme tools are available at http://strive.lshtm.ac.uk/resources/parivartan-girls-programme-tools.

References

- Bankar, S., M. Collumbien, M. Das, R. K. Verma, B. Cislaghi, and L. Heise. 2018. “Contesting Restrictive Mobility Norms among Female Mentors Implementing a Sport Based Programme for Young Girls in a Mumbai Slum.” BMC Public Health 2018 Apr 10;18 (1): 471. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5347-3.

- Barker, G., D. Doğruöz, and D. Rogow. 2009. “And How Will you Remember me, my Child? Redefining Fatherhood in Turkey.” In Quality/Calidad/Qualité, p. 34. New York: The Population Council.

- Cislaghi, B., S. Bankar, M. Collumbien, L. Heise, and R. K. Verma. Forthcoming. “Daughters Negotiating and Mothers Strategizing Access to a Sport Based Programme for Young Girls in a Mumbai slum.”

- Cislaghi, B., and L. Heise. 2018. “Four Avenues of Normative Influence: A Research Agenda for Health Promotion in low and mid-Income Countries.” Health Psychology 37 (6): 562–573. doi: 10.1037/hea0000618

- Coalter, F., and J. Taylor. 2010. Sport-for-development Impact Study. A Research Initiative Funded by Comic Relief and UK Sport and Managed by International Development Through Sport. Stirling, Scotland: University of Stirling.

- Connell, R. 2012. “Gender, Health and Theory: Conceptualizing the Issue, in Local and World Perspective.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (11): 1675–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006

- Dworkin, S. L., P. J. Fleming, and C. J. Colvin. 2015. “The Promises and Limitations of Gender-Transformative Health Programming with Men: Critical Reflections From the Field.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (sup2): 128–143. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751

- Goldstein, N. J., and R. B. Cialdini. 2007. “Using Social Norms as a Lever of Social Influence.” In The Science of Social Influence: Advances and Future Progress, edited by A. Pratkanis, 167–192. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

- Guest, A. M. 2013. “Sport Psychology for Development and Peace? Critical Reflections and Constructive Suggestions.” Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 4 (3): 169–180. doi: 10.1080/21520704.2013.817493

- Hayhurst, L. M. C. 2013. “Girls as the ‘New’ Agents of Social Change? Exploring the ‘Girl Effect’ Through Sport, Gender and Development Programs in Uganda.” Sociological Research Online 18 (2): 8. doi: 10.5153/sro.2959

- Jewkes, R., M. Flood, and J. Lang. 2015. “From Work with men and Boys to Changes of Social Norms and Reduction of Inequities in Gender Relations: a Conceptual Shift in Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls.” The Lancet 385 (9977): 1580–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4

- John, N. A., K. Stoebenau, S. Ritter, J. Edmeades, and N. Balvin. 2017. “Gender Socialization During Adolescence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Conceptualization, Influences and Outcomes.” In Innocenti Discussion Paper 2017–01, p. 61. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti.

- Khurshid, A. 2015. “Islamic Traditions of Modernity:Gender, Class, and Islam in a Transnational Women’s Education Project.” Gender & Society 29 (1): 98–121. doi: 10.1177/0891243214549193

- Kidd, B. 2008. “A new Social Movement: Sport for Development and Peace.” Sport in Society 11 (4): 370–380. doi: 10.1080/17430430802019268

- Kippax, S., N. Stephenson, R. G. Parker, and P. Aggleton. 2013. “Between Individual Agency and Structure in HIV Prevention: Understanding the Middle Ground of Social Practice.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (8): 1367–1375. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301301

- McAllister, F., A. Burgess, J. Kato, and G. Barker. 2012. Fatherhood: Parenting Programmes and Policy - a Critical Review of Best Practice. London: Fatherhood Institute/Promundo/MenCare.

- Miller, E., M. Das, R. Verma, B. O’Connor, S. Ghosh, M. C. D. Jaime, and H. L. McCauley. 2015. “Exploring the Potential for Changing Gender Norms among Cricket Coaches and Athletes in India.” Violence Against Women 21 (2): 188–205. doi: 10.1177/1077801214564688

- Morris, M. W., Y.-y. Hong, C.-y. Chiu, and Z. Liu. 2015. “Normology: Integrating Insights About Social Norms to Understand Cultural Dynamics.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 129: 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.03.001

- Panter-Brick, C., A. Burgess, M. Eggerman, F. McAllister, K. Pruett, and J. F. Leckman. 2014. “Practitioner Review: Engaging Fathers – Recommendations for a Game Change in Parenting Interventions Based on a Systematic Review of the Global Evidence.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 55 (11): 1187–1212. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12280

- Paul, T. 2011. “Space, Gender, and Fear of Crime Some Explorations From Kolkata.” Gender, Technology and Development 15 (3): 411–435. doi: 10.1177/097185241101500305

- Phadke, S. 2007. “Dangerous Liaisons: Women and Men: Risk and Reputation in Mumbai.” Economic and Political Weekly 42 (17): 1510–1518.

- Ridgeway, C. L. 2009. “Framed Before we Know it: How Gender Shapes Social Relations.” Gender and Society 23 (2): 145–160. doi: 10.1177/0891243208330313

- Srivastava, M., and Z. Sumrani. 2012. “Case Study: All aboard the Magic Bus.” South Asian Journal of Management 19 (3): 123–144.

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.