ABSTRACT

This article makes a case for a reconceptualisation of aid and development programme design. Specifically, it questions the role of the international “development expert” in the design and implementation process. We argue that by employing “design thinking” as a guiding principle, the way in which aid programmes are envisaged and delivered can be radically overhauled, resulting in dramatically improved outcomes for the users of aid. We argue that practical improvements in delivery are achievable through locally rooted, “user-driven” development solutions that originate from the beneficiaries themselves. Design thinking as applied here goes significantly further than other programme design and implementation methodologies that champion locally owned, needs-driven assistance. Furthermore, we make a case for this approach addressing wider problems within the sector, namely the perception, in some quarters, that aid is intrinsically “neo-imperialist” in design and ideologically driven.

Introduction

This article is about the role of experts in development and redefining how we think about helping strangers. In particular, we make a case for trusting people to help themselves.

There is currently a great deal of cynicism about the role of experts among the general public in donor countries, epitomised by U.K. minister Michael Goves' infamous retort that “people in this country have had enough of experts”. While this article in no way endorses such a view, we do question the degree to which development has become such an expert-led sector. Specifically, we question the way in which expert-designed programmes crowd out the voices of those who understand the challenges best; the users of aid. Here we define “users of aid” as individuals, organisations, groups, and governments who are affected by taxpayer and donor-funded aid and development programmes, typically in developing and transitioning countries. The term, therefore, covers many potential actors within the “donor/recipient” framework that governs North–South relations. What they have in common, despite differences in terms of power and levels of engagement, is their position with respect to donor-driven notions of development and how these might be achieved.

We argue, instead, that experts and expertise are important to the process of development but not in the manner that the present model is currently conceived. We make a case for a form of beneficiary-led aid (Flint and Meyer zu Natrup Citation2014) facilitated and supported by experts, but not defined by them. In particular, we position ourselves at odds with the “expert as saviour” approach in which technocrat international development consultants, occasionally but not always relevant country experts, are parachuted into communities to address local development issues. Rather, we outline a model of development based on “design thinking” – one focused on the users of aid as co-creators of all relevant programme details; a model that involves a transfer of power from the funders of aid to the users of aid. We argue that this approach, while redefining how aid is practised, is nonetheless actionable within current parameters. At its core, it demands a change in mindset, redefining what “development expertise” entails and how aid is delivered. We argue that the approach brings numerous benefits – to donors and users alike – with respect to value for money, and, more importantly, effectiveness and sustainability.

The article is set out as follows: we outline weaknesses within current aid delivery models, detail how a model incorporating design thinking might address the challenges raised, offer a view of how the approach might operate in the “real world”, and assess the implications of such an approach to the sector as a whole.

A broken model

“Aid doesn’t work” is a refrain we hear regularly in parts of the media in countries like the U.K. “Why is YOUR cash given to foreign dictators” asks the Daily Express. “Misplaced charity” argues the Economist, “U.K. aid money: generosity or wasted spending?” asks the B.B.C., “New report confirms that aid money is wasted (we told you so)” crows a TaxPayers’ Alliance media release. An Ipsos MORI poll in 2012, which surveyed opinions across 24 countries, found that a majority of respondents (51%) believed that their country’s aid spending was wasted. The 2018 Oxfam scandal has done little to improve this public trust. This is not to say that people don’t believe that aid is important, but that there is increasing scepticism with respect to how it is spent. Even the most ardent supporters of aid spending would be prepared to admit that funds could be better targeted and better spent.

The literature surrounding aid is vast, and academic debates on aid have raged for over half a century (Rostow Citation1960; Frank Citation1971; Baran Citation1973; Wallerstein Citation1974; World Bank Citation1990). More recently, in the wake of movements like “Make Poverty History”, themselves inspired in part by the U.N. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a “great aid debate” has arisen, pitting opposing ideological perspectives against each other and affording their proponents a certain degree of celebrity status. The two “stars” of this debate over aid have unquestionably been Dambisa Moyo (who came to prominence with her bestselling book Dead Aid) and her “opponent” Jeffrey Sachs (whose book The End of Poverty has become a core text on many university reading lists). While not necessarily household names, both have developed high media profiles. Moyo (Citation2010) represents a “radical” school of thought on aid, heavily shaped by neo-liberal logic, demanding an end to aid (the argument put forward is that aid exacerbates poverty). This school of thought also includes analysts like William Easterly (Citation2006) and Robert Calderisi (Citation2006). Unlike Moyo, Calderisi (Citation2006) does not demand an end to aid, but a halving of funding on the basis the smaller budgets are easier to manage and there is less scope for corruption and mismanagement. On the other side are the proponents of aid, led by Sachs (Citation2005), who argue that while there are issues with respect to implementation, aid can offer a way out of poverty – high profile allies include Giles Bolton (Citation2007), Paul Collier (Citation2007), Jonathan Glennie (Citation2008), and Amartya Sen (Citation1999). Leftwing critiques, more in the tradition of Marxist/dependency (critical) theorists of the 1960s and 1970s, have also contributed to the debate, albeit with less of a profile – for example, Paulette Goudge (Citation2003), Kothari and Minogue (Citation2002), and Yash Tandon (Citation2009).

What unites them all, at the most basic level, is a view that aid does not always work in the way that it is intended. Unfortunately, with respect to this nearly 15-year-old great debate, actionable solutions for the sector as a whole remain thin on the ground. Drawing on our disciplines of academia (Flint) and aid worker (Meyer zu Natrup) respectively, we propose a “simple” solution – that all aid and development programmes “on the ground” need to start with the direct involvement with those affected.Footnote1 We posit that current models of “consultation” and “participation” are largely box-ticking exercises, with little meaningful impact on how aid is delivered (Cooke and Kothari Citation2001; Mohan Citation2001; Flint and Meyer zu Natrup Citation2014). Given the lack of meaningful input from affected communities, it is little surprise that aid projects and programmes fail. They fail because they are poorly designed, with little genuine understanding of the end user. While this point is generally acknowledged, little has been done over the past decades to actively change how aid is delivered. Instead, what we observe is a continuous tweaking of the model, to little effect. Without direct input, from the beginning, by the users of aid, little of substance can be achieved.

Accordingly, we do not argue against aid but rather the way in which it is practised. This in itself is not particularly novel (or novel at all). Unlike critical theorists (Kothari and Minogue Citation2002; Goudge Citation2003; Tandon Citation2009), we don’t look to the structural level, but look instead to how aid programmes are conceived and operationalised. We find, quite simply, that as aid and development programmes are not designed for specific intended users, they cannot work. Innovations like needs assessments toolkits have seen improvements, but have not solved the problem of poor programme outcomes.Footnote2 The key problem with such tweaks is that aid and development design, even with the best needs assessments (which are rarely done), is formulaic in nature. In order to work, experts need to be engaging with users, not focused on established questionnaire and focus group templates.

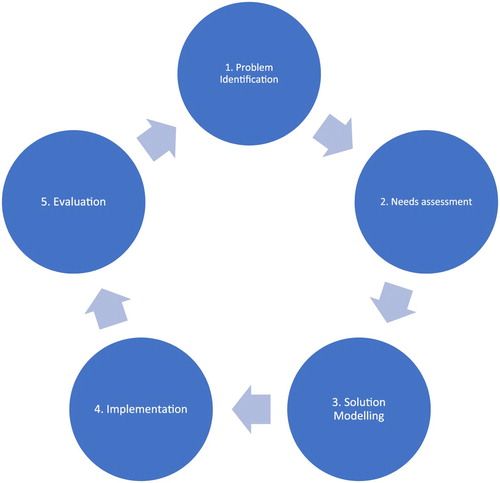

As set out in , a typical design cycle for any aid or development programme consists of five main stages. While some donors and implementers might seek to extend the needs assessment period and insert inception phases during the implementation phase, the timeframe in which the aid-affected community can be engaged is limited. This model, driven by a results-based management methodology and focused mainly on demonstrating value for money, does not allow for a truly collaborative co-creation process. Using private sector language is helpful here in making the point that, in short, the aid “product” is developed and tested without ever really asking the “consumers” what they require.

A key failing in many critical (leftwing) approaches to the question of aid is that while the critiques have merit and, in many respects, the injustices of the global economic order are unquestionably part of the development conundrum, such approaches rarely offer “actionable” solutions short of overwhelming (and revolutionary) structural change. While our approach can be viewed as “problem solving”, we situate ourselves some way from both the Sachs and Moyo schools. We propose an opportunity for radical change but within the current system and framework; change capable of delivering a range of achievable gains while not denying the need for greater justice within the global political economy more generally. Importantly, we focus on the process inherent in developing such programmes rather than the end result. At present, aid programmes are result rather than process orientated, leading to less than optimal outcomes. What we propose instead is a model that focuses on the process of aid delivery and development programme design, trusting the participants to arrive at their own desired goals. It is important to stress that we are talking about the goals of those at whom the aid and development funds are directed, here defined as aid users. Under this scenario, the aid sector, largely headquartered in the Global North, will serve as an “eco-system” for providing funding, technical assistance, research capacity, and project delivery infrastructure. It does not, however, set the aims of what is to be done. This represents a fundamental change with respect to agendas pertaining to goal-setting on the part of donors, who are asked to (partially) fund programmes while giving up a significant degree of control.Footnote3 The model presupposes moving away from any target-driven governing frameworks even, for example, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – trust needs to be at the core of the process, there cannot be caveats if genuine empowerment is to take place. In this sense, the model proposed can be described, for want of a better phrase, as “radical reformist”. Our reformist approach radically expands the engagement of aid users beyond extractive needs assessments (essentially sites for data mining) towards meaningful co-creation. With this in mind, we envision a user-driven process of programme design based on multiple iterations and rapid “prototype” testing, resulting in bespoke programmes (not programmes derived from templates).

A design thinking model of development

It is uncontroversial to state that, while advances in user consultation and needs assessment have been made, donor programmes remain top-down expert-led affairs. As sets out, the basic model, familiar to all in the sector, from major international financial institutions like the World Bank, bilateral agencies like USAID and DFID, private charitable bodies like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and NGOs, runs along predictable lines. Operationally, the benefits of this problem-solving approach, derived and adapted to some extent from expert-dependent fields like engineering and management (e.g. product development science, lean management, and total quality management techniques), are that donors can subscribe to a “rational”, “evidence-driven” and “goal-orientated” approach that has clearly defined procedures and parameters. Over the last 20 years, in order to make the process more “human”, earnest endeavours to make global development and aid efforts more participatory have been introduced. However, even in the best examples, development experts have succeeded only in making the programmes slightly more participatory. In effect, the underlying ownership of the work remains with the donor, imposing its vision (however benignly intended) on the poor. The current model relegates the users of aid to the sidelines; they are “programme takers”, not “programme makers”, regardless of levels of consultation and participation. The model we propose addresses this underlying problem of ownership that results in so many aid and development programmes failing.

There are numerous problems with the model in that any development practitioner will be familiar with (see, e.g., “insider” accounts like Mosse Citation2005; Bolton Citation2007). Based on our personal experience in the field, we focus specifically on the following key problems: the experts brought in to design the programme frequently have insufficiently nuanced local knowledge, they are not embedded; needs assessments are conducted with little real input from affected communities (generally used for data mining); solutions are modelled in accordance with established practices and often ideologically – and politically – informed; programmes are implemented by outsiders brought in on short-term contracts; and programmes are evaluated in accordance to narrowly defined criteria. Furthermore, programme goals are often aspirational, rather than addressing more modest, but realistic targets. Crucially, it is difficult to factor empathy into the model. We maintain that in order to really understand a set of development or aid problems, empathy is vital. Empathy is not merely a feeling of sympathy, but a genuine experience of the problems, the context in which they exist, the people and organisations affected and the reality in which the aid and development challenge sits. Empathy requires deep emersion and embedding into the context, beyond that of expert-led political economy analysis or needs assessments.

The process described above is linear in progression and offers little scope for learning and iteration. The linearity stems directly from established donor funding models, which require having to move from programme design, to implementation, to evaluation in distinct phases. Accordingly, as a general rule, a programme is designed, implemented, and audited and, after three to four years, written up as being completed. We propose a more reflexive and organic model based on design thinking and abductive reasoning, one that is user driven. Design thinking, as practised in sectors like IT and management consulting, offers a useful starting point. The term “design thinking” was coined by Peter Rowe (Citation1986), although the process as we currently understand it was pioneered by organisations like IDEO in the early 1990s. Proponents have argued that linear ways of thinking – deductive and inductive – prevent imaginative/innovative solutions to problems. Design thinking offers the introduction of “intuition” into the thinking process, achieved by embracing uncertainty and even chaos, with only a vague sense of the end product (Brown Citation2009). Although the term has become something of a buzzword within business (and often stripped of most of its meaning), this methodology might offer a radical solution to the problems that have beset development and aid programmes over the past few decades.

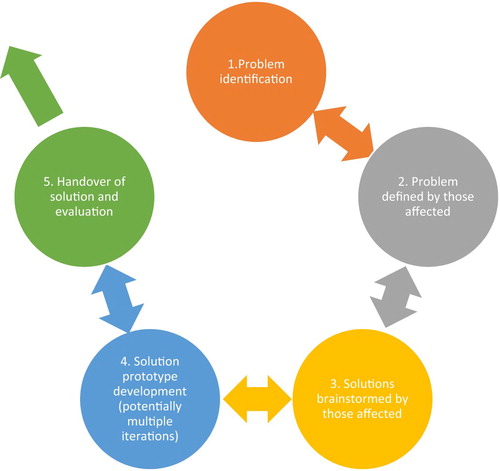

Within design thinking, the solution is not known at the start (the project has a “fuzzy front end”). Neither is the process intended to deliver the “product”. It involves, instead, an acceptance by the designer that they might not have sufficient knowledge to complete their project on their own. Within design thinking in the IT sector, for example, in application or software development the user is engaged from the start and is a co-creator in the process. The first priority for application developers is determining what the user wants and how the user will engage with the product. The IT expert’s role is to “reverse engineer” a solution based on user needs and requirements. This involves the expert embedding themselves with the users, observing and questioning (keeping an open mind and not making judgments). Furthermore, it involves rapid prototyping with a view to testing (on the expectation that the majority of early versions will fail or be inadequate). The process is built on a feedback loop, involving numerous iterations of the design. It also involves “learning by doing”. In this sense, initial failure is integral to the process. The bulk of the process is focused on ideation and testing. The process is reflexive, not linear – as outlined in .

Steps 1 and 2 bring the designer and end users together. It is easy to assume that “problem identification” is obvious whereas, in reality, without effectively identifying the problem, the search for a solution becomes meaningless. Step 3 takes the “solution” away from the designer and places it in the hands of the intended end users who then collaborate to find solutions. In step 4, the designer, in consultation with the end users, produces prototypes which can then be tested (with the expectation that many will fail before a workable solution is arrived at). In step 5, the finished product is handed over to the end users who are then free to embark on a process of continual refinement by re-engaging with the process when necessary, thereby creating an ongoing feedback loop. As stated, this is a reflexive and dynamic process, involving multiple reptitions and iterations, with any of the five steps potentially being repeated numerous times. The point to emphasise is that it is only through this seemingly “messy” abductive process that a tailor-made “product” can be achieved. By definition, in terms of scale and reachability, the process will need to start with a fairly defined group of end users, at least to begin with.

At the heart of the process is trust that the users understand the “problem” and know what they want or need. The benefits of the model in IT, and other sectors are incontrovertible, and have enabled the development of some iconic products – applications like PayPal, Spotify and products like the Smart car being just a few examples. Apple, Google, Accenture are examples of companies that have placed a significant degree of emphasis on design thinking. The conceptual leap in transferring work practices from the IT and management consulting sectors to the development and aid sector might seem something of a stretch and potentially controversial but, we contend, lessons can be learnt.

Within the development and aid sector, the “customer” is largely excluded from the design process, despite the fact that they will be the “end users”. Although there have been developments with respect to actual product design for people facing specific challenges in developing countries (a “human design thinking approach”), this approach has not been expanded to embrace development and aid programmes at a sectoral level.Footnote4

So how to engage the “customer”? Aid experts are usually parachuted in – they often have little knowledge of conditions on the ground (even if the experts are country specialists, no expert can claim expertise on every area and sector within that given territory and few experts would have the time to deeply immerse themselves and develop real empathy). Yet local knowledge is crucial to the success of any project. This is hardly a revelation and programmes are now designed with a heavy emphasis on consultation and participation. However, such consultation is, by definition, “quick and dirty” and, given financial and time constraints, can never hope to capture local conditions. A design thinking approach would address this fundamental issue from the outset – aid users would be asked to identify key problems and help identify solutions themselves. The expert’s job would be to facilitate proposed solutions.

A key area to be addressed before proceeding is the use of language and the jargon in which design thinking is framed. To reduce development to a consumerist interaction between “end users” and “service providers” is not what is intended. We are not proposing a business model as a way forward but rather a “thinking model”. This model is predicated on aid beneficiaries being the shapers and drivers of the development process from the outset. It is a methodology that is profoundly democratising and built on genuine respect and co-ownership. It offers the basis for a system of development provision which puts beneficiaries at the centre of the decision-making process. It is, in effect, the operationalisation of what can be viewed as beneficiary-led aid (Flint and Meyer zu Natrup Citation2014).

What a design thinking model of aid might look like in practice

The design thinking-inspired model is actionable and appropriate to “real world” engagement (rather than an idealised wish list of proposals). According, we offer an overview, based on personal professional engagement with projects similar to that outlined below, of how the model might be actionable. For reasons of confidentiality and to prevent conflict of interest, no specific programmes are identified. Instead, the example we set out represents, based on our experience, a fairly typical composite of projects that will be familiar to anyone who has worked on, or observed, aid donors and contractors in action.

Our composite “problem” considers the issue of local government capacity in a developing country. In this example, the local authority is poorly staffed and resourced, and is struggling to provide efficient and accountable public services to its population. Standard processes like the issuance of business licences takes too long, and applicants are often successful only when bribing officials (who can revoke licences at will). Such actions hurt the local business community and make it impossible to create sufficient local growth and employment. Traditional needs assessments have identified the underlying issues as being economic underdevelopment, socially and culturally as sanctioned corruption, a shortage of skills within the local authority, and less than efficient administrative systems and processes.

This represents a fairly standard problem of service delivery by local authorities in any number of developing countries. Based on the commissioned needs assessments and participatory exercises with the local authority, the donor designs terms of reference for a four-year capacity building and anti-corruption programme. A key focus for the donor is to involve civic service organisations in order to hold the government to account. In addition, the donor publishes a tender for the work systems and processes to be analysed and improved. The remaining aspects of the programme are then also put out to tender, a process that can frequently last more than six months.

Typically, during the inception phase, contractors report low motivation and ownership on the part of local authority officials, with a demonstrably notable reluctance to attend training sessions or cooperate in the systems review. In addition, contracted NGOs working on anti-corruption projects report threats against staff members, difficulties in obtaining visas, and other work impediments. The result is that while all of the associated projects are managed by highly trained and professional development contractors – and some successes are often achieved – the projects fall behind schedule and the possible impact of the funding is diminished. However, in keeping with the established model, “success” is usually defined in terms of milestones rather than hard to quantify (especially in the short term) achievements, such as training sessions completed, system reports written and anti-corruption advocacy conducted. In essence, the programme is assessed as being “successful”, despite having subsequently been found (in the long term) to have little effect.

In terms of design, this is a system that is donor directed, expert devised, and expert implemented. Proponents of the model might argue that the percentage of national staff at implementing organisations has steadily increased over the past few years, but this does not detract from the fact that the aid users are rarely, if at all, meaningfully consulted. Reflecting the process illustrated in , “the problem” is identified and analysed by experts, a solution devised (usually with a degree of participatory input), and a plan then executed. Needs assessments, generally the basis for “on the ground” data, are methodologically limited and only offer very partial insights into the needs and wants of intended end users. In short, the experts generating “the solution” never form a clear picture of the affected community; it is simply not possible. They are far away from experiencing real empathy for the people concerned, the context and the problem. Nonetheless, “the solution”, once devised and signed-off, then becomes a programme blueprint, with little room for reflexivity, learning or iteration over the next three to four years. An unintended consequence of the rigid programme design is an inability for involved experts to incorporate lessons learnt, and indeed to learn any lessons in the first place. The system actively, if unintentionally, discourages reflexivity. Although the solution identified by the donor and its contractors is usually participatory in some form, local voices are not part of devising it. Throughout the work, the donor and its contractors remain directive. A design thinking approach would reconceptualise the programme outlined above differently, specifically with respect to addressing the role of expert inputs.

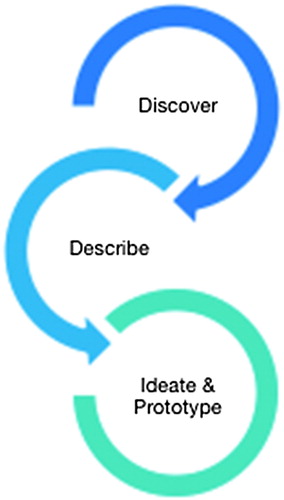

shows our proposed design thinking methodology. This would not appear new to many in the IT, management consulting, and some engineering disciplines, but its application to the development and aid sector would represent something of a paradigm shift. Rather than identifying a particular problem “from above”, the “discovery stage” focuses on extensive community engagement – the focus is to identify a set of aid and development challenges like an anthropologist might, a more observational approach, in dialogue with the local community and over an extended period of time. The aim of the “discover” and “description” phases is to find and agree an accurate description of a set of problems, ambitions and wishes as well as to build true rapport and trust with the future aid users. This takes time. Community identified responses are then tested through a process of joint idea finding and rapid “prototyping”, resulting in an ever-intensifying test environment. This is repeated a number of times. “Failure” is an integral part of the process and involves testing by “doing”. This in turn generates knowledge and experience, as well as builds trusts. The role of the international development expert is to facilitate the community’s ownership of the project and to provide funding in order to action the bespoke prototypes. The ability of the implementing organisations to rapidly scale up and develop programme prototypes is, therefore, more important than their established credentials on running development and aid programmes.

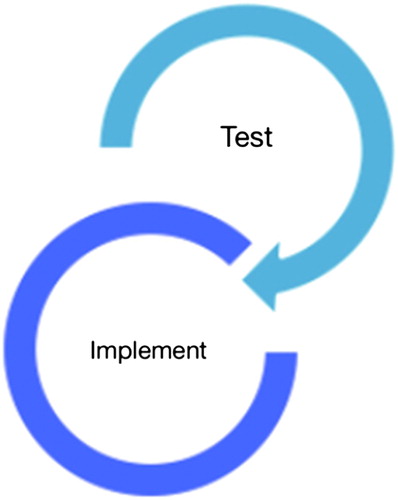

It is important to stress that the expert is there to assist in making the community’s plans work, not to devise the programme itself. The expert merely facilitates the process and provides a platform for all stakeholders to input that which is not automatically rooted in the local power structures. The emerging ideas are then expert developed and tested. Failure is not only acceptable but viewed as part of the learning process. Consequently, any solutions identified would be shaped by local knowledge and expertise, ensuring a far greater degree of programme sustainability – this in turn would allow donors to exit the programme far earlier in the process than would have been the case in the traditional programme design methodology. Phase 2 of the programme’s development is illustrated in of the programme development process.

Having developed several prototypes and allowed them to fail at various stages in the programme development process, promising solutions to the development or aid challenge are then tested. Testing is different from prototyping in several key aspects: (1) tests are done under as scientific conditions as possible (e.g. control groups, random testing, etc.); and (2) considerably larger sample sizes are used than in the prototyping. Failure or limited success of the solution is still very possible. The community, with facilitation from the expert and/or implementing organisation, will then have to decide carefully how long to test a possible solution before declaring it a failure or success. The temptation to declare success at an early stage must be resisted. When the community is satisfied with the test, only then will the solution be implemented (this will require patience on the part of donors, accepting that the process cannot be rushed). This last stage is not very different to current forms of implementing development and aid projects, except that the extensive prototyping and testing of the solution will provide a much better basis for impact assessment as comparative values and data of previous, non-executed solutions will be available for comparison. Design thinking evolved development and aid solutions will have, therefore, the significant advantage that the “holy grail” for development and aid practitioners is more likely to be achieved: solid impact data.

In practice, a design thinking approach to the “case study” outlined above would look something like the following: the expert would observe how services were delivered by the local authority by embedding themselves in the local community for an extended period. A similar process would occur within the local authority. The community would be asked to identify key failings in delivery and highlight their concerns and frustrations. These data would then be relayed to the local authority. The expert would sit down with local authority personnel and solicit their responses. Personnel would be asked how to best respond to the problems raised and how they might be best addressed. These discussions would then be brought together as specific policy initiatives that would be rolled out in quick succession (as pilots). What makes this process different to extractive needs assessment or traditional community engagements is the fact that the pilots will represent the solutions the authorities and the community have agreed together. This approach brings both key stakeholders together, invests them in the success and holds them to account. The community, after an implementation period, would be asked to reflect on these pilots, changing their design to address unforeseen problems (the model is not changed for them, but by them) they might have encountered. Local policymakers would then refine or discard initiatives, dependent on their success and workability. This rapid prototyping approach would be continued until a sustainable solution was achieved. Importantly, the role of the expert is one of facilitation, not direction. In this scenario, there is no ideal state or predetermined end goal (the programme has a “fuzzy front end”). The “leap of faith” is in trusting local people to find local solutions (to borrow from Ayittey). At a stroke, accusations of neo-imperialism and Western-centric agendas are removed, as are problems of “ownership” and sustainability.

Various design elements can further support ownership and sustainability, through a focus on joint funding initiatives, improved consultation, and improved donor exit strategies. The model does, however, present potential problems for donors, namely a loss of control and public perceptions of such an approach in donor countries. Specifically, there is the issue of trust, that the users of aid can be trusted to make the “right” decisions when left in charge of the process. This might be especially true if solutions do not “look right” when reported in the media. Public reaction to innovations like cash transfers in sections of the U.K. media has been tinged with suspicion, “Queue here for U.K.’s £1bn foreign aid cashpoint: Just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse … YOUR cash is doled out in envelopes and on ATM cards loaded with money”, proclaimed the Daily Mail in January 2017, in response to a U.K.-funded project in Pakistan. The article argues that as “much as £300million is being lavished on a scheme in Pakistan that has been dogged by claims of corruption”. This headline outlines some of the potential challenges facing the aid and development sector when innovation is attempted. Despite the “indignation” apparent in such stories, cash transfer programmes are one of the most successful type of programmes funded by DFID and other donors. What makes cash transfers successful is the same principle that makes design thinking a potentially successful development and aid management technique. The advantage of providing cash to aid users is to provide them with choice, flexibility, dignity, and acknowledging that those in need understand their needs best.

There are additional benefits to a design thinking approach for the development and aid sector more generally. The approach offers tangible advantages in how programmes are devised, executed and monitored. Importantly, over and above context-specific gains, the approach facilitates reflexivity and creative (abductive) thinking, breaking out of the cookie-cutter mould that has dominated the sector for so long. Furthermore, it addresses failures in knowledge transfer between development and aid contractors. Initiatives funded by donors that have aimed to enhance the transfer of knowledge between aid practitioners have mostly not proven sustainable and have generally petered out once the funding period has finished. Design thinking development programmes, however, will automatically be customised to local context, power structures and actors, these being the usual impediments to successful knowledge transfers. This leads to significantly improved programming targeting. Community-driven development, aid and peacebuilding projects frequently fail because they are not understood, desired or supported by the community they are supposed to assist. Local power structures, notwithstanding earnest analysis of the prevailing political economy, are seldom understood and it is even rarer that they are monitored during the project period. By placing project ownership in the hands of the affected community, these issues are addressed.

Conclusion

The role of the expert and programme implementing organisations in directing and implementing development and aid programmes requires rethinking. Until such a shift occurs, the problems that have affected the sector will remain unresolved and the “great aid debate” will continue to rage. We have argued, instead, that by adopting a design thinking approach to such programmes, one that places aid users at the heart of the design process, this debate might be resolved. While user participation and community consultation processes have improved over recent decades, they remain expert led. By reconceptualising aid as something that is driven by local knowledge and expertise, with the development expert as facilitator, we contend that the issues that have beset the sector can be overcome. As shown, this approach, while certainly radical, is perfectly actionable with the current system. However, it does require that ideologically driven goals be put to one side and an acceptance – in a real rather than rhetorical sense – that “one size fits all” approaches are doomed to fail. In order for this to be achieved, aid users must be trusted to know and understand the context in which they are operating, which represents a significant degree of divergence from how development and offer aid are currently practised. If this leap can be made, a sector driven by bespoke beneficiary-led aid programmes is possible. This, in turn, will provide donors with value for money, proof of impact, and aid users programmes that actually address their needs. Most importantly, it is more likely to deliver the help and support that millions need, in the form they need it, while retaining their dignity to choose and become the leaders in their own development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Adrian Flint is a Senior Lecturer in Development Politics at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS) at the University of Bristol. His main research interests lie within the field of North–South relations and include issues like health and development (particularly HIV/AIDS), global trade, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development.

Christian Meyer zu Natrup is the Director and Head of Advisory at MzN | International Development Experts, leading a team of consultants working with NGOs, donors and governments. His main research interests lie within the field of development assistance and humanitarian aid, including issues like the practical management of programmes, programme targeting, private sector involvement in development and operational excellence.

Notes

1 The ‘simple’ solution relates to the spending of funds already agreed by donors, on the ground. We do not make any claims to address all the challenges facing the sector; for example, we do not address commitments, levels of funding, the effects of geopolitics, or the desire to use of aid as tool for foreign policy.

2 A needs assessment is a tool designed to help experts ascertain the key concerns of a given group. Having identified what these might be, the needs are ranked according to perceived importance. They are generally generated through interviews and surveys of affected individuals. However, much of their value is determined by constraints on time, resources, and access.

3 Our programme design methodology favours co-financing models.

4 Groups like IDEO work specifically to help design products for people living in poorer developing countries. IDEO products include innovations like affordable solar lanterns and lost-cost sensors for farmers to monitor moisture in the soil. See www.ideo.org.

References

- Baran, P. 1973. The Political Economy of Growth. London: Penguin.

- Bolton, G. 2007. Aid and Other Dirty Business: An Insider Reveals How Good Intentions Have Failed the World’s Poor. London: Random House.

- Brown, T. 2009. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. New York: HarperCollins.

- Calderisi, R. 2006. The Trouble with Africa Why Foreign Aid Isn't Working. New Haven, CO: Yale University Press.

- Collier, P. 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cooke, B., and U. Kothari. 2001. “The Case for Participation as Tyranny.” In Participation: The New Tyranny, edited by B. Cooke, and U. Kothari, 1–15. London: Zed Books.

- Easterly, W. 2006. The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Flint, A. G., and C. Meyer zu Natrup. 2014. “Ownership and Participation: Towards a Development Paradigm Based on Beneficiary-Led Aid.” Journal of Developing Societies 30 (3): 273–295. doi: 10.1177/0169796X14536972

- Frank, A. G. 1971. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. London: Penguin.

- Glennie, J. 2008. The Trouble with Aid: Why Less Could Mean More for Africa. London: Zed Books.

- Goudge, P. 2003. The Power of Whiteness: Racism in Third World Development and Aid. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Kothari, U., and M. Minogue. 2002. “Critical Perspectives on Development: An Introduction.” In Development Theory and Practice: Critical Perspectives, edited by U. Kothari, and M. Minogue, 1–15. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Mohan, G. 2001. “Beyond Participation: Strategies for Deeper Empowerment.” In Participation: The New Tyranny, edited by B. Cooke, and U. Kothari, 153–167. London: Zed Books.

- Mosse, D. 2005. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moyo, D. 2010. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is Another Way for Africa. London: Penguin.

- Rostow, W. W. 1960. The Process of Economic Growth. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Rowe, P. 1986. Design Thinking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sachs, J. 2005. The End of Poverty: How We Can Make It Happen in Our Lifetime? London: Penguin.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

- Tandon, Y. 2009. “Aid Without Dependence: An Alternative Conceptual Model for Development Cooperation.” Development 52 (3): 356–362. doi: 10.1057/dev.2009.36

- Wallerstein, I. 1974. “The Rise and Future Demise of the World Capitalist System.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 16 (4): 387–415. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500007520

- World Bank. 1990. Problems and Issues in Structural Adjustment. Development Committee Pamphlet No. DEV 23. Washington, DC: The World Bank.