ABSTRACT

In Africa, policymakers and development practitioners focus heavily on making farming more attractive for the youth. To reach this goal, different actions are proposed, often emphasising the need for modern technology. These proposed actions are mostly based on anecdotes and prior policy beliefs. Using interviews and drawing exercises, this article shows that the aspirations, opinions and perceptions of adolescents (pre-youth) and youth are more diverse than assumed by the prevailing orthodoxies. The findings suggest that policymakers and development practitioners should pay more attention to their views, comprising environmental and social concerns, to avoid misguided policies.

Introduction

In the international development community, there is a strong narrative that “the rural youth” in developing countries finds farming unattractive. This picture has sparked much concern more recently with growing evidence of a “youth bulge” in numerous developing countries, many of which are located in Africa (Sommers Citation2011). Based on the projected need to generate millions of new work opportunities, the need to make farming more absorptive and attractive for young people has received much attention. To make farming more attractive, policymakers and development actors have formulated different, mostly technology based propositions. These range from promoting mechanisation (Sims, Hilmi, and Kienzle Citation2016), information and communication technologies (CTA Citation2016), secure and affordable access to land (Berckmoes and White Citation2016; Bezu and Holden Citation2014; White Citation2012), to saving groups (Flynn and Sumberg Citation2018) and seeing farming as a business (FAO Citation2014). Some propositions go beyond the nature of farming and emphasise the need for rural areas to change, for example, through infrastructure development (Porter et al. Citation2010; Sumberg et al. Citation2017; White Citation2012).

The first part of the “youth finds farming unattractive” narrative is echoed in studies suggesting resentment of the youth against farming or under current conditions (Leavy and Hossain Citation2014; Tadele and Gella Citation2012; White Citation2012). However, there are also studies suggesting that young people have very diverse attitudes towards farming and rural areas (Berckmoes and White Citation2016; Kristensen and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013; Sumberg et al. Citation2017). This is reflected by an SMS-based survey conducted among 10,000 young people in Africa by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). When asked where they would like to live, either rural or urban, in five years’ time, 52% of respondents answered “that depends” (Melchers and Büchler Citation2017).Footnote1 However, they did not specify the conditions on which this depends.

In contrast, the second part of the narrative on proposed actions has received limited scientific attention (Anyidoho et al. Citation2012; Sumberg et al. Citation2012). This is because much of the work on rural youth has either focused on the first part or has been conducted with a quantitative focus on their aspiration levels. Aspirations are defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “a hope or ambition to achieve something”. To assess aspiration levels, researchers have used proxies such as desired educational achievements, occupation and income (Beaman et al. Citation2012; Bernard and Taffesse Citation2014; Knight and Gunatilaka Citation2012; Kosec, Hausladen, and Khan Citation2014). All of these approaches have been critiqued. For example, questions on income often lack anchoring and questions on preferred occupation are ambiguous as respondents stating farmer as preferred occupation may still have highly diverging aspirations. Still, such proxies have allowed researchers to study the effects of aspirations on different outcome variables (such as technology adoption and school achievements).Footnote2 However, focusing on aspiration levels alone provides no evidence on what people aspire (the “something”) and how farming needs to look like to be attractive for the youth. From the perspective of policymakers, such quantitative assessments of aspirations may thus lack direction for guidance.

Given the research vacuum on the second part of the narrative, policy actions to make farming (and the rural space) more attractive for young people lack an empirical base as there is little research on what the youth needs to find farming attractive. Instead, stakeholders rely on narratives and storylines based on anecdotes (Sumberg et al. Citation2012). These may be purposely or accidentally selected based on prior ideas and policy beliefs (Anyidoho et al. Citation2012; Mockshell and Birner Citation2015). The lack of empirical research has created the opportunity to misuse the youth to forward specific agendas and support existing policy beliefs. For example, the MasterCard Foundation claims that the youth needs access to rural finance (Alemayehu and van der Drift Citation2015) and machinery conglomerate AGCO argues that the youth needs farming to be more mechanised (AGCO Citation2017).

Investigating the views of the adolescents and youth can be challenging using traditional data collection methods. Quantitative data collection methods with close-ended questions may fail to capture important nuances of aspirations, opinions and perceptions. Also, the use of predefined response options when using quantitative methods can add researcher bias. Qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews can help to overcome these challenges but face constraints when working with adolescents and youth. For example, adolescents and youth may lack linguistic proficiency and may feel guard-railed by questions or intimidated by the presence of researchers (Chamber et al. Citation2018; Einarsdottir, Dockett, and Perry Citation2009; Literat Citation2013). Thus, this article uses a novel method in this context: participatory drawings. Drawings allow respondents to reflect slowly on their aspirations, opinions and perceptions. In this paper, drawings were used as a qualitative method to generate insights into what young people aspire with regard to farming as well as to understand their perceptions about urban and foreign life. However, drawings may also be used by future studies to quantitatively assess aspiration levels.

This article aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the aspirations, opinions and perceptions of young people in developing countries, particular in rural Africa. It argues that a better understanding of the youth and what they want is key to formulate policies and programmes that better fit with the actual views of the youth, and thus make farming truly attractive. One of the research questions explores the youth’s views of the settings of the lifestyle and the rural community they currently live in. Given the role of urban areas and foreign countries as benchmarks for the formulation of perceptions, the paper also asks about their views on cities and foreign countries. Lastly, it explores the youth’s aspirations of the future settings of the lifestyle and set-up of farming by asking how they imagine their future farm in 10 years’ time. The first two questions assess opinions and perceptions, while the latter question allows a qualitative assessment of what type of farming the youth aspires. Particular attention will be paid to gender differences in answers to these questions.

Research design and methods

This study used a novel method to explore aspirations, opinions and perceptions in this context, the use of future-oriented drawing exercises. This method was complemented with in-depth interviews. Both methods were applied in the Eastern Province of Zambia. Combining these two methods allowed triangulation of the collected data.

Drawings

To facilitate the exploration of the young people’s aspirations, opinions and perceptions, four drawing exercises were organised. The use of drawings has long been used by psychologists, for example, to talk with traumatised children in post-war situations. More recently, the use of drawings has received attention by social scientists, again with a strong focus on exploring delicate topics, for example to give a voice to victims of violence, homeless children and AIDS orphans (Mitchell et al. Citation2011). The studies use different techniques. To better understand how children see themselves, for example, they let them draw themselves in the rain (Glewwe, Ross, and Wydick Citation2018).Footnote3 The use of drawings is not constrained to delicate topics, however. For example, Chamber et al. (Citation2018) have asked children to draw their future job (e.g. pilot or nurse). While the method has been mainly used with children, Literat (Citation2013) argues that the method is also particularly suited when working with youth.

Using drawings instead of face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions has several advantages, some of which may be more pronounced in rural areas of developing countries. In Zambia, due to cultural norms, children and early youth may not feel free to express themselves in an interview with a researcher (or more general an older people or authority) or during a group discussion with other children. Facing an entirely white blank page with only one objective (to draw freely on a certain topic) allows respondents to draw and think slowly about their aspirations, opinions and perceptions – without being guard-railed by questions and/or intimidated by the presence of the researchers, which may be particularly relevant for shy children (Chamber et al. Citation2018; Einarsdottir, Dockett, and Perry Citation2009). Einarsdottir, Dockett, and Perry (Citation2009) note the difference in answers when children are asked to draw compared to when they are asked in interviews. While Einarsdottir et al. focus on children aged 4–6 years, their findings may be relevant for older children. In addition, using drawing makes it possible to “access those elusive hard-to-put-into-words aspects of knowledge that might otherwise remain hidden or ignored” (Weber Citation2008, 44). Lastly, drawings are a visible proof of research findings (Mitchell et al. Citation2011).

The drawing exercises were organised in collaboration with schools. The school children were allowed to choose one or more of three topics:

How do you imagine your future farm/your own farm in 10 years’ time?

How do you imagine town/ city life?

How do you imagine the life in other countries?

Interviews

In total, 53 young people, out of which 44 were adolescents (between 10 and 19 years old) were interviewed with the help of local enumerators who spoke the same language as the respondents and had the same gender. Before, the interviews, it was explained that the research was not part of any programme to discourage bias. Interviews were structured around four main themes. First, respondents were asked questions about how they find farming. They were also asked to reflect on how to address the challenges of farming. The second theme focused on rural areas. In the third topic, they were asked to reflect about city life. For the fourth theme, they were asked questions about their perceptions of foreign countries. Questions were asked without prompting any answers but respondents were encouraged to further explain their views. To encourage reflections and obtain clear statements, respondents were asked follow-up questions like: “You told us about the life in villages and towns. In 10 years, where would you rather want to live? Why?”

Study sites and participants

The study focused on young people in the Eastern Province in Zambia. The agricultural sector of the Eastern Province is dominated by smallholder farmers. On average, farmers cultivate 2.3 ha of land (IARPI Citation2016). Own or hired tractors are used by 1% of the households; 57% use animal traction; and the remaining households use hand tools (IAPRI Citation2016). The use of fertilisers is common but few households have access to herbicides and improved seeds (IAPRI Citation2016). Average household income is low and 90% of the rural population live on less than 1.25 US$/day (IARPI Citation2016). In 2010, the secondary school attendance rate was 40% in rural areas (CSO Citation2014). Average youth literacy rate, with youth being defined as ranging from 15 to 24 years, was 75%, with lower levels for females (72%) and rural youth (72%) (CSO Citation2014). Within the economically active youth population, with youth here being defined as ranging from 15 to 35 years, the urban unemployment rate was 24% and the rural rate was 9% (CSO Citation2014). According to newspaper and NGO reports, both teen pregnancy and child marriage rates are high (Girls not Brides Citationn.d.; Zambia Reports Citation2019).

The study was conducted in three different communities in two districts of the Eastern Province (Vubwi, Chipata), which differ in terms of rural infrastructure and distance to towns. However, all the communities were rural, none was semi-urban or urban. In all three communities, interviews were conducted with young people. In total, 53 young people were interviewed, with respondents between the ages of 9 and 20. Respondents were selected using the random walk method whereby starting from one point of the community every xth household was selected, depending on the community. In addition to the interviews, four drawing exercises were organised with two schools (Chinjala Basic School and Kambwatike Basic School). In each school, two drawing exercises were organised with two different classes, Grade 8 and Grade 9. The age of the participating students ranged from 13 to 20.

Quality assurance

To ensure scientific rigour, the standards of qualitative research were followed. As suggested by Bitsch (Citation2005), using both interviews and drawing exercises ensures credibility and confirmability (methodological triangulation). The interviews with the young people were done until a point of saturation was reached (persistent observations). The findings were discussed with research peers (peer debriefing). The emerging findings from the drawing exercises were discussed with research participants (the children) and experts (member checks).

Results

provides an overview of frequent perspectives that emerged during both the interviews and drawing exercises. It shows that the youth has competing views on farming, rural and urban life, and on foreign countries. In many cases, these views were forwarded by the same respondents, suggesting that they have a nuanced understanding on the positive as well as the negative aspects of farming, rural and urban life, and foreign countries. In other cases, respondents emphasised either positive or negative aspects. This results section elaborates on the perceived positive and negative sides of all themes in detail by referring to representative statements from respondents themselves, and by showing examples from the drawing exercises. The next section shows the perceptions of the youth towards farming and their own future, and is based only on the interviews. The subsequent three sections refer both to the interviews and the drawing exercises.

Table 1. Overview of perspectives.

Perceptions about farming

What do the young people think about farming? Some of the respondent statements fit the widespread discourse that rural youth finds farming unattractive and thus provide a dark picture of farming. Farming is portrayed as a labour-intensive and burdensome occupation with little reward. These statements describe farming as not guaranteeing a regular income. In addition, they highlight the risky nature of farming, especially due to the dependence on fluctuating rainfall patterns. This negative perspective can be illustrated by the following statements:

All the farming jobs are so hard. You can easily get a leathery [sic] age. (Noah, 17)

There is nothing good in farming. When I winnow dusts get into my lungs. (Esther, 17)

Other professions are assured of salary. Farming is seasonal and depends on rain. (Adam, 16)

Working on field the whole day is tiresome, especially during ploughing and weeding time. But the harvesting comes with so much joy and the food helps us against hunger. (Esau, 17)

I enjoy farming, it feels nice to plant and to work at home. Only ridging is difficult. I never considered doing something else than farming. I want to be rich with farming. (Helene, 14)

I like all farming activities and will continue. Through farming I find food and energy to work again. (Friday, 19)

I want to work as a police officer. Then I can hire people who can work for me or a tractor. And I can buy more fertiliser. (Alik, 14)

I want to be a nurse and farm at the same time. With my salary I can support my family as well. (Esther, 17)

I want to work with the government. Maybe a nurse to help the poor. Then I am paid monthly. I only stay in village if I will not be educated. (Lozi, 16)

I will see how I will perform. If I do well, I will become a teacher or doctor or police officer. If not I will continue farming. (Noah, 17)

Aspirations, opinions and perceptions on the future farm

Young people were asked about how they envision their “future farm/their farm in 10 years” during the in-depth interviews and the question was also formulated as a task during the drawing exercises. During the interviews, most respondents envisioned owning draught animals, some because they would like to cultivate more land than what is possible with manual labour. In contrast, owning tractors was rarely mentioned. The following answer to a follow-up question sheds light on why:

Animals can do all activities, ploughing, and ridging, weeding and even transport. Tractors just use fuel and stand around. (Josifine, 15)

The results from the drawing exercises largely echo those from the interviews, but some aspects were new. shows the frequency of certain themes from the drawing exercise and the stand-alone interviews. For this purpose, we coded the drawings into categories. As shown by , farm diversity was one of the most frequent themes drawn by the students. Gender also played a role with regard to the some of the aspirations. For example, 37% (49%) of the females drew fruits (vegetables) as compared to 4% (29%) of the males. Females also referred to trees more often than males, both during the drawing exercise and the interview. also depicts the higher desire to use animal traction (44%) compared to using tractors (6%) during the drawing exercise. Females referred to the status quo, using hand tools, more often, but they also referred to animal traction and some mentioned tractors. With regard to living standards, better housing (86%) and access to own water source (49%) was more frequently drawn than access to electricity (13%) and media devices (10%). In regard to water pumps we see gendered differences: girls more often drew them.

Table 2. Frequency of themes during drawing exercises.

The frequency of themes mentioned during the interviews differs from the frequency of themes drawn by the students. First, the frequency of most themes is much lower. This was due to the nature of the semi-structured interviews, were respondents had much less time to think. When asked about their future farm they usually mentioned only a few core themes. Here, themes that may be perceived as not very special have been left out, for example, the existence of various crops and trees on their future farm was a frequent theme during the drawing exercise but less so during the interviews. On the other side, difficult to draw themes, such as the use of more fertilisers (45%) and land expansion (38%) feature more prominently now. The continuous use of hand tools was not a theme occurring here, potentially because respondents focused on things they want to upgrade. With regard to the use of animal traction and tractors, we see no difference in the frequency of themes when comparing drawing exercise and interviews.

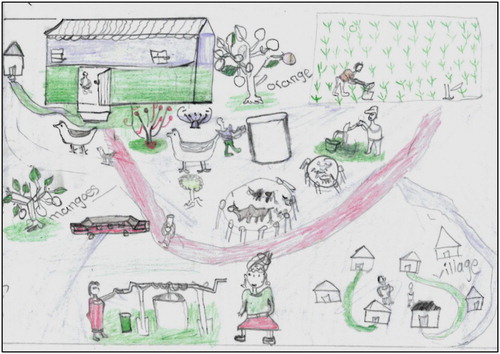

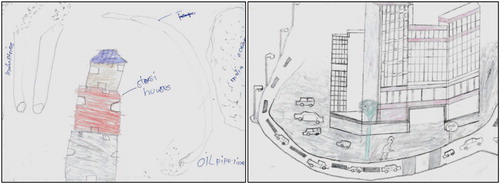

shows a typical future farm has envisioned during the drawing exercise. We see the prominent role of owning fruit trees (mangoes and oranges) and growing vegetables as well as having easy access to water sources. Farming continues to be done by hand, but we also see a car.

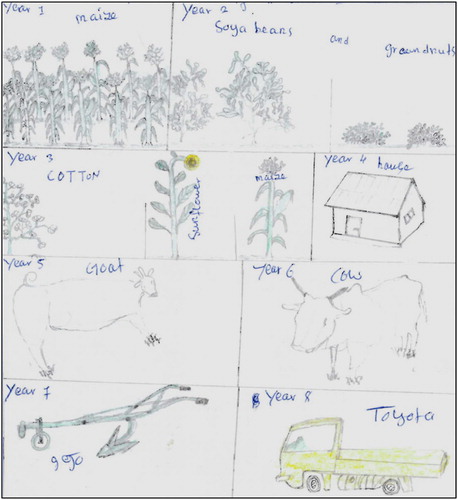

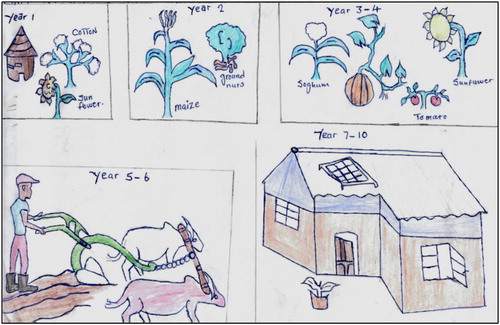

Interestingly, most of the students in the drawing exercises had a clear understanding of how they aimed to attain their future farm. In most cases, this pathway started with the diversification of farm production during the first years. This included growing additional cash crops besides maize (such as sunflowers and cotton) and at a later stage also vegetables and fruits. After some years, they would buy some animals (first small ones such as chickens; then larger ones such as goats and later also cows) and equipment for using animal draught power for land preparation, weeding and transportation. The time component of aspiration and the pathways to the future farm can best be illustrated by drawings (see and ).

Rural versus urban life

The results on the perceptions about rural and urban life suggest that the views of young people on this topic are very diverse. Around half of the respondents (53%) stated during the interviews to prefer rural over urban life, with no difference by gender. This suggests the need to discard the idea of an automatic flow of the youth towards urban areas. For these respondents, rural life was perceived as having several advantages. One of the most prominent was that rural life is characterised by a large degree of freedom and independence. In addition to this, the respondents empathised the social embeddedness and dense social networks that characterise rural areas for them. Both perspectives are highlighted in the following quotes:

We do not need to pay for anything. We do not pay for maize, land, water and fruits such as mangoes. In town they need to pay for everything, even water. Here we have nutritious food. (Ruth, 15)

We have a lot of interaction with our neighbours. In our community you can always get help. (Raymond, 17)

Prefer village because I have always been there. I am happy in village and farming. (Josifine, 15)

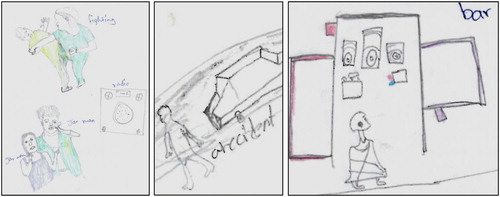

Some people do not have respect in town. They are poisoned by alcohol and they fight and smoke. (Talunsa, 15).

People are not friendly and do not help each other. They do not have a heart to help. (Esau, 17)

There are a lot of mad people, and Satanism and disabilities. (Modesta, 12)

Figures 7–11. “City life” from Harrson (16), Raimond (15), Mysterious (17), Margret (16), and Vincent (15).

In town they have a lot of things, schools, electricity and roads and even upstair houses [sic]. The people do not look so scruffy. Town life is good life. (Christopher, 14)

In town, they do not farm, they stay at home and are just chatting and eat a lot of sausages. (Patrick, 13)

In town, parents work and the youth can stay at home. (Blaxon, 15)

I do not know which work but Indian shops always have work available. (Obista, 15)

Jobs in town are much lighter but difficult to find. I wouldn’t want to go there without a good plan. (Noah, 18)

In the village, we always eat the same, beans and nshima, and we need to work hard. (Elina, 16)

In the village, you can be bewitched over small disputes and the fields are very small. I prefer to live in town. (Jakob, 15)

Some of my friends want to go to town but others want to stay. Of the ones who went many came back after some years. (Alik, 14)

I want to raise some money in town but then I want to move back to my villages. I will bring a tractor with me and cultivate a lot of land then. (Raimond, 17)

Foreign countries

During both the interview sessions and drawing exercises, respondents were asked about their perceptions of foreign countries. Similar to their views on urban life, their views varied between attraction and fear. Some admired foreign countries as being clearly advantageous. They highlighted that these countries have access to good education, health and roads, as the following quotes show:

This is where good things are and no problems. (Monika, 16)

They have schools and good clinics. And some countries use electric stoves. I would like to see this. (Josifine, 15)

I heard about other countries from radio. There is a lot or starvation and hunger. And people disappear also. You cannot move at night there. (Modesta, 12)

People are dying there from lightning and civil war and Boko Haram. (Maiko, 17)

I would not want to go. I feel much safer in Zambia. (Axon, 16)

Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to a deeper understanding of the aspirations, opinions and perceptions of young people. In this context, the common orthodoxy contends that young people are pulled and pushed away from farming and rural areas and that the promotion of modern technologies such as tractors and ICTs can make farming more attractive. The results presented here reject this view as overly simplistic. It does not reflect the diversity of aspirations, opinions and perceptions of young people. Similar to Sumberg et al. (Citation2017), the results suggest that the youth does not speak with one but with several voices and even single respondents may articulate multiple voices. Most of the respondents have a nuanced understanding about the good and bad sides of farming as well as rural, urban and foreign life. In this context, they consider trade-offs, for example, between the social embeddedness of rural life and the better amenities of urban areas. In contrast to the common orthodoxy, many young people expressed interest in farming and joy in living in their villages and showed pride to be self-sustaining and independent. This strongly resembles findings from Berckmoes and White (Citation2016) and Kristensen and Birch-Thomsen (Citation2013). This suggests that the rural space can be an attractive place given appropriate policies (Kristensen and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013; Melchers and Büchler Citation2017). Yet, the respondents were not blind to the challenges of farming and rural areas, and stressed the risk associated with farming. Crucially, to some extent respondents may build their own narratives to justify their decisions and to maintain self-respect (Locke and te Lintelo Citation2012). For example, when deciding to continue farming they may stress the good aspects of farming while pinpointing the negative sides of town life. In discourse analysis, this behaviour is referred to as positive self-representation and negative other-representation.

The findings resonate with the concept of opportunity spaces which argues that youth reflects and manoeuvres actively around their geographical, socio-economic and policy opportunity space (Sumberg et al. Citation2012; Sumberg and Okali Citation2013). The perceived opportunity space of the youth may have increased during the last decade due to exposure to new media such as television and smartphones that shows lifestyles different from subsistence farming, although respondents had little (direct) access to new media. The perception that people work little and do only easy tasks in towns may be grounded in these phenomena. As highlighted by Sumberg et al. (Citation2012), the ability to use opportunity spaces depends on knowledge and skills, social networks, gender, and risk attitudes. How exactly these factors work is not clear, however. For example, a high level of knowledge and skills may raise the chances of utilising an opportunity space but may also lead to a more nuanced (and realistic) perception about own opportunities and therefore to a lower likelihood of exploring that place. For example, some respondents emphasised the idea of moving to urban areas to find work, but only if they did well in school. Similarly, social networks including peers, role models and parents may encourage young people to use opportunity spaces. Sumberg et al. (Citation2017) have shown that parents encourage their children to leave farming in Ghana. On the other hand, social networks may also lead to social pressure that restrains young people from leaving farming and rural areas (Leavy and Hossain Citation2014). The widespread view that cities are characterised by Satanism may be interpreted in this regard. When asked about the sources of these views respondents who have not themselves seen cities brought up relatives or church.

The large diversity of different aspirations, opinions and perceptions was also present in regard to the fictional “future farm” of the young respondents. Imagining their future farm, the most frequent answers centred on low-tech solutions such as increasing farm diversity and using draught animals – aspects that are not captured by the common orthodoxy that emphasises the need for modern technology and ICTs. To some extent, this may be due to the lack of knowledge about certain technologies. However, for example, the young people in the study areas were exposed to tractors but still rarely imagined them as being part of their future farm and rather drew draught animals. This may reflect “low” levels of aspirations (tractors may be attractive but the young people do not dare to aspire them). However, many respondents aspired similar expensive things (such as cars). In addition, the respondents stated clear reasons for preferring draught animals.

While one could argue that this is again a form of negative other-representation (respondent do not like tractors because they cannot have them), it seems that the youth does indeed find unique advantages of draught animals over tractors. In combination with the frequently aspired higher farm diversity, this may suggest that ways of farming “close to nature” such as agro-forestry practises could contribute to increase the attractiveness of farming. In combination with the importance of social structures – an implication from the interviews – this suggests that the current discourse to make the rural space and farming more attractive neglects non-material aspects of aspirations such as environmental social factors (King Citation2018). This seems to be true in particular for females, who aspired more diverse farms and trees and more often referred to hand tools than animal traction and machinery. This may be because of lower aspirations per se or because animal traction and machinery are considered things for males.

The study used a combination of two research methods, which allowed for the exploration of aspirations, opinions and perceptions of the youth. Using these techniques has allowed us to broaden the concept of aspirations from quantitative measurements of levels to more nuanced qualitative understandings of what people aspire and which leverages the youth aims to use to reach these levels. Such an approach provides much more guidance to policymakers. Combining two research methods allowed us to triangulate our data collection process, and ensured that we explored themes that may have remained hidden by using only one method. For example, abstract and/or difficult to draw concepts such as Satanism, land expansion and even the use of more fertilisers were mentioned frequently during the in-depth interviews but were not expressed during the drawing exercise. On the other hand, the aspiration to have a future farm with a large variety of crops, fruits, vegetables, animals and trees was a strong finding distilled from the drawing exercise and the associated follow-up interviews, but these things were much less frequently articulated during the stand-alone interviews.

Some methodological questions remain, for example, on how the respondents perceive the likelihood of their drawings becoming reality, which would be expectations rather than aspirations. So far, our analyses have remained mainly qualitative. However, the drawings could also be analysed and coded with scores to calculate aspiration levels (as done by Glewwe, Ross, and Wydick Citation2018 to calculate self-esteem levels).

Conclusion

This study showed that the rural youth has very diverse aspirations, opinions and perceptions. In contrast to the literature, young people were found to reflect carefully about the positive and negative aspects of farming, rural and urban life, and of foreign countries. With regard to their future farm, they again showed a large diversity of aspirations, opinions and perceptions – some which have been neglected both by policymakers and development practitioners. While policymakers and development practitioners highlight the need for modern technologies and ICTs, young respondents emphasised more low-tech solutions such as raising farm diversity, using draught animals and having electricity, hence the reference to bulls and bulbs in the title of the paper. This suggests that policymakers and development practitioners need to pay more attention to the actual aspirations, opinions and perceptions of the rural youth, comprising environmental and social concerns, to avoid well-intended but misguided policies. The findings also suggest that there cannot be one policy for “the youth”. Rather, there is a need for several policies to reflect several types of rural youths. Avoiding misguided policies will be key to ensure that the potentials of the emerging youth bulge can be reaped, while minimising its risks. The empirical findings can be relevant not only for Zambia but also for the large set of African countries that currently aim to make farming more attractive to rural youth. However, as the findings may be largely country and context-specific, they should not be understood as blueprint solutions but rather as a stimulus to formulate agricultural policies more closely in line with the rural youth in mind.

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to all young people participating in the study for their patience and many insightful moments, and to the headmasters of the schools who helped organise the drawing exercises. I am also grateful for financial support from the Program of Accompanying Research for Agricultural Innovation, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development. Thanks to Regina Birner for her valuable comments and her excitement about the topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Thomas Daum is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Agricultural Science in the Tropics, Hans-Ruthenberg-Institute, University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany. His research focuses on governance and institutions as well as agricultural development strategies that are sustainable from an economic, social and environmental perspective. He is part of the Program of Accompanying Research for Agricultural Innovation (PARI), which aims to contribute to sustainable agricultural growth and food and nutrition security in Africa and India.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This does not provide any hints on whether the young people actively choose either rural or urban space for their living or whether they are passively “just waiting” as there are no opportunities in rural or urban spaces (Locke and te Lintelo Citation2012).

2 An emerging strand of research links technology adoption behaviour of farmers with the aspirations of their children. For example, some studies suggest that farmers may not adopt long-term technologies (such as agro-forestry or soil conserving practices) if their children aspire to move out of agriculture (Mausch et al. Citation2018; Verkaart, Mausch, and Harris Citation2018). Knowing this can help to enhance the targeting of technology promotion and research priority setting.

3 These drawings are assessed based on, for example, whether the children drew themselves using an umbrella, smiling, or whether the sun was shining (Glewwe, Ross, and Wydick Citation2018).

References

- AGCO. 2017. “Agribusiness in Africa. Organizing Farmers of the Future.” Accessed 12 January 2018. http://agco-africa-summit.com/review.html.

- Alemayehu, K., and R. van der Drift. 2015. “Agriculture as a Business for Youth in Africa.” MasterCard Foundation. Accessed 12 June 2018. www.mastercardfdn.org/envisioning-agriculture-as-a-business-for-youth-in-africa.

- Anyidoho, N. A., H. Kayuni, J. Ndungu, J. Leavy, M. Sall, G. Tadele, and J. Sumberg. 2012. “Young People and Policy Narratives in Sub-Saharan Africa.” FAC Working Paper 32. Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Beaman, L., E. Duflo, R. Pande, and P. Topalova. 2012. “Female Leadership Raises Aspirations and Educational Attainment for Girls: A Policy Experiment in India.” Science 335 (6068): 582–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1212382

- Berckmoes, L. H., and B. White. 2016. “Youth, Farming, and Precarity in Rural Burundi.” In Generationing Development, 291–312. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bernard, T., and A. Taffesse. 2014. “Aspirations: An Approach to Measurement with Validation Using Ethiopian Data.” Journal of African Economies 23 (2): 189–224. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejt030

- Bezu, S., and S. Holden. 2014. “Are Rural Youth in Ethiopia Abandoning Agriculture?” World Development 64: 259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

- Bitsch, V. 2005. “Qualitative Research: A Grounded Theory Example and Evaluation Criteria.” Journal of Agribusiness 23 (1): 75–91.

- Chamber, N., E. Kashefpakdel, J. Rehill, and C. Perc. 2018. Drawing the Future. Exploring the Career Aspirations of Primary School Children from Around the World. London: UCL Institute of Education, the National Association of Head Teachers and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Education and Skills.

- CSO. 2014. Census of Population and Housing. Eastern Province Analytical Report. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office.

- CTA. 2016. “ICTs for Agriculture – Opportunities for Youth, Smart Solutions for Farmers.” Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation. Accessed 12 June 2018. www.cta.int/en/article/2016-04-22/icts-for-agriculture-n-opportunities-for-youth-smart-solutions-for-farmers.html.

- Einarsdottir, J., S. Dockett, and B. Perry. 2009. “Making Meaning: Children’s Perspectives Expressed through Drawings.” Early Child Development and Care 179 (2): 217–232. doi: 10.1080/03004430802666999

- FAO. 2014. Youth and Agriculture: Key Challenges and Concrete Solutions. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Flynn, J., and J. Sumberg. 2018. “Are Savings Groups a Livelihoods Game Changer for Young People in Africa?” Development in Practice 28 (1): 51–64. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1397102

- Girls not Brides. n.d. “Zambia.” Accessed 25 March 2019. www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/zambia.

- Glewwe, P., P. H. Ross, and B. Wydick. 2018. “Developing Hope among Impoverished Children: Using Child Self-Portraits to Measure Poverty Program Impacts.” Journal of Human Resources 53 (2), 330–355. doi: 10.3368/jhr.53.2.0816-8112R1

- IAPRI. 2016. Rural Agricultural Livelihoods Survey Report. Lusaka: Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute.

- King, E. 2018. “What Kenyan Youth Want and Why It Matters for Peace.” African Studies Review 61 (1): 134–157. doi: 10.1017/asr.2017.98

- Knight, J., and R. Gunatilaka. 2012. “Income, Aspirations and the Hedonic Treadmill in a Poor Society.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 82 (1): 67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2011.12.005

- Kosec, K., S. Hausladen, and H. Khan. 2014. “Aspirations in Rural Pakistan.” Pakistan Strategy Support Program Policy Note 3 (August). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Kristensen, S., and T. Birch-Thomsen. 2013. “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Rural Youth Employment in Uganda and Zambia.” International Development Planning Review 35 (2): 175–201. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2013.12

- Leavy, J., and N. Hossain. 2014. “Who Wants to Farm? Youth Aspirations, Opportunities and Rising Food Prices.” IDS Working Paper 439. London: IDS.

- Literat, I. 2013. “‘A Pencil for Your Thoughts’: Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 84–98. doi: 10.1177/160940691301200143

- Locke, C., and D. J. te Lintelo. 2012. “Young Zambians ‘Waiting’ for Opportunities and ‘Working Towards’ Living Well: Lifecourse and Aspiration in Youth Transitions.” Journal of International Development 24 (6): 777–794. doi: 10.1002/jid.2867

- Mausch, K., D. Harris, E. Heather, E. Jones, J. Yim, and M. Hauser. 2018. “Households’ Aspirations for Rural Development through Agriculture.” Outlook on Agriculture 47 (2): 108–115. doi: 10.1177/0030727018766940

- Melchers, I., and B. Büchler. 2017. “Africa’s Rural Youth Speak Out.” Rural 21. 03/2017.

- Mitchell, C., L. Theron, J. Stuart, A. Smith, and Z. Campbell. 2011. “Drawings as Research Method.” In Picturing Research, edited by L. Theron, C. Mitchell, A. Smith, and J. Stuart, 17–36. Leiden: SensePublishers.

- Mockshell, J., and R. Birner. 2015. “Donors and Domestic Policy Makers: Two Worlds in Agricultural Policy-Making?” Food Policy 55: 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.05.004

- Porter, G., K. Hampshire, M. Mashiri, S. Dube, and G. Maponya. 2010. “‘Youthscapes’ and Escapes in Rural Africa: Education, Mobility and Livelihood Trajectories for Young People in Eastern Cape, South Africa.” Journal of International Development 22: 1090–1101. doi: 10.1002/jid.1748

- Sims, B. G., M. Hilmi, and J. Kienzle. 2016. “Agricultural Mechanization: A Key Input for sub-Saharan Africa Smallholders.” Integrated Crop Management 23: 2016. Rome: FAO. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308777106_Agricultural_mechanization_A_key_input_for_sub-Saharan_African_smallholders

- Sommers, M. 2011. “Governance, Security and Culture: Assessing Africa's Youth Bulge.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 5 (2): 293–303.

- Sumberg, J., N. A. Anyidoho, J. Leavy, D. J. te Lintelo, and K. Wellard. 2012. “Introduction: The Young People and Agriculture ‘Problem’ in Africa.” IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00374.x

- Sumberg, J., and C. Okali. 2013. “Young People, Agriculture, and Transformation in Rural Africa: An “Opportunity Space” Approach.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 8 (1–2): 259–269. doi: 10.1162/INOV_a_00178

- Sumberg, J., T. Yeboah, J. Flynn, and N. A. Anyidoho. 2017. “Young People’s Perspectives on Farming in Ghana: A Q Study.” Food Security 9 (1): 151–161. doi: 10.1007/s12571-016-0646-y

- Tadele, G., and A. A. Gella. 2012. “‘A Last Resort and Often Not an Option at All’: Farming and Young People in Ethiopia.” IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 33–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00377.x

- Verkaart, S., K. Mausch, and D. Harris. 2018. “Who are Those People We Call Farmers? Rural Kenyan Aspirations and Realities.” Development in Practice 28 (4): 468–479. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1446909

- Weber, S. 2008. “Visual Images in Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by G. Knowles, and L. Cole, 41–54. London: Sage.

- White, B. 2012. “Agriculture and the Generation Problem: Rural Youth, Employment and the Future of Farming.” IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00375.x

- Zambia Reports. 2019. “Eastern Province 2018 Teen Pregnancy Tally Hits 24,731.” Accessed 25 March 2019. https://zambiareports.com/2019/01/04/eastern-province-2018-teen-pregnancy-tally-hits-24-731.