ABSTRACT

One criticism of how women’s empowerment is operationalised in development interventions is the lack of consideration of its context specificity. This quantitative study investigates how women participants in development projects in Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam perceive the meaning of empowerment and the associated positive effects of participating in empowerment activities. The findings indicate that women’s ideas of empowerment differ according to their cultural, economic and social contexts as well as from donor-driven definitions. Both similar and distinct positive effects of participating in empowerment activities are felt, highlighting the importance of incorporating what women prioritise when planning empowerment projects.

Introduction

Over the past decades, the empowerment of women has become a key aspect of international development. The term “women’s empowerment” originally appeared in the feminist discourse in the 1980s and since then has become widely adopted in the policy vocabulary of development organisations (Calvès Citation2009). According to a popular definition, empowerment “is the process by which women take control over their lives, acquiring the ability to make strategic choices” (United Nations Economic and Social Council Citation2002). Yet it is worth noting that there are many definitions provided by different institutions and scholars. Similarly, many indexes of empowerment such as WEI (Women Empowerment Index) or GEM (Gender Empowerment Measure) offer a list of “ingredients” or recipe that usually cover different dimensions of women’s lives, including political, social, cultural and economic dimensions. These are useful to understand both the interrelated dimensions of empowerment and to measure where progress is made and where challenges remain towards gender equality. However, they are not necessarily reflective of different ways one may feel empowered or may not help us understand how different contexts may call for more adapted responses that would increase a sense of empowerment in the short term despite structural barriers that may take more time to address.

One well-known definition of empowerment is provided by Kabeer (Citation1999) who conceptualised it based on a model comprising three interrelated dimensions: (i) access to material, human and social resources (the pre-conditions for making strategic choices); (ii) agency, defined as the ability to set one’s goals and act upon them (the actual process of exercising choice); and (iii) achievements, such as, for example, improved wellbeing (the outcome of making choices). This conceptualisation of empowerment is important in that it defines empowerment both as a process (1) (2) and as an outcome (3), which raises the question of whether the same processes lead to the same outcomes in different contexts.

While it is clear that progress has been achieved in empowering women in many parts of the world (UNFPA Citation2019), challenges have been highlighted both with its process and outcome. A major criticism that has been voiced with respect to how women’s empowerment is operationalised in gender-related policies and programmes is that the meaning of empowerment is often defined from the vantage point of the developed world, in particular Western societies, which does not do justice to the context specificity of empowerment, especially with regards to the means or process available and the specific local barriers one may face. Whether empowerment has been defined externally or implemented through generic measures is not without consequences since most of the funding for empowerment activities is provided by Western donor agencies. Beyond the issue of properly translating the term into different languages and keeping its original meaning in English (on the challenge of translating empowerment, see Doane and Doneys Citation2015), this context is relevant to both how empowerment is understood and how it shapes local and or cultural barriers to its effective implementation. As elucidated in Kabeer (Citation1999) in the late 1990s, factors that might be an indication of empowerment in one cultural context may have different meanings elsewhere. In line with this, O'Hara and Clement (Citation2018) found that the forms of agency promoted by international agricultural organisations are not always consistent with local perceptions of what empowerment is. Nepalese women in their study area who were engaged in the cultivation and sale of vegetables at a local market were supposed to be “empowered” in the sense of increased agency in terms of decision-making, mobility and control over income. However, their study showed that the women themselves perceived carrying their agricultural produce to the market as a heavy physical burden. Moreover, the income they earned was too low to significantly improve their bargaining power. Engagement in vegetable farming, one could argue in this case, rather reinforced women’s traditional, subordinate status within their household. These challenges may just reflect poor implementation of empowerment activities, but they also indicate how one may prioritise different resources, for instance time over income.

Similarly, according to Meinzen-Dick et al. (Citation2019), increases in women’s income, another popular objective of empowerment initiatives that is often seen as a means for women to have a greater voice within their household, can have detrimental effects on family harmony, in the form of conflicts between wife, husband and other family members, especially if women earn more than their husbands. Disruptions of traditional family and/or gender relations can be both necessary and positive. However, in some contexts, possible negative consequences of such disruptions, such as intimate partner violence and social sanctioning, can outweigh the positive effects of increased income, and thus call for complementary approaches to income generation. Ladič (Citation2015), for instance, found that economic development and access to resources, which is often a strong focus of empowerment programmes, does not necessarily have only positive effects on women’s lives. In her study, female domestic workers in Rwanda reported that traditionally they were allowed to leave their house in order to fetch water and thus able to meet other people. However, since having been given access to running water, their employers did not allow them to leave their compound anymore.

In addition to differences between developed and developing countries, perceptions of the meaning of empowerment can also vary across developing countries and over time. Priorities with regards to dimensions of empowerment may differ. For example, the ability to visit a health centre without having to ask for permission from a male family member might be perceived as a form of empowerment by women in rural Bangladesh, whereas women in urban Peru who are used to freedom of movement in public may prioritise control over income for better health outcomes. Moreover, the use of contraception was a sign of women’s empowerment in rural Bangladesh in the early 1990s, while nowadays contraception has become the norm and is unlikely to be prioritised for women’s empowerment to the same extent (Malhotra and Schuler Citation2005). Sometimes it is not that existing empowerment measures are wrong or irrelevant, but that they may not address specific ways that women may feel more empowered. Porter made this important point regarding the central role of security to women’s empowerment in many developing and war-torn countries (Porter Citation2013). Similarly, Doneys, Doane, and Norm (Citation2020) found that measures to reduce domestic violence can be key to increasing self-confidence and therefore a pre-requisite to more income-based forms of empowerment. The lack of formal health security and social protection in some countries without basic public protections or insurances can also undermine efforts towards women’s empowerment (FAO Citation2015).

Related to differences in understandings of what constitutes empowerment is the question of how women’s level of empowerment should be measured. Development organisations and governments depend on such measures in order to evaluate the effectiveness of their gender-related interventions. International development organisations commonly evaluate their empowerment or gender equality programmes using composite indices that combine several key indicators. An overview by the United Nations (Citation2015) shows that most empowerment indices focus on women’s health, political participation and economic status in terms of income and labour force participation. These indices are usually based on universally applicable indicators, which are deemed relevant for all countries and thus neglect the context-specificity of empowerment. This is not to say that these types of indexes are to be rejected, but they need to be complemented with more relevant ways to assess empowerment in different contexts.

Providing development practitioners and policymakers with information regarding local definitions of empowerment is important as it allows them to tailor respective interventions to different contexts. When using local perceptions of what constitutes empowerment to help design interventions, the reasons for the existence of diverse perceptions need to be carefully taken into account. For instance, a shift of women’s priorities away from their family or social group toward a more individual orientation has often been stated as a desirable goal of empowerment interventions (Fierlbeck Citation1995; Jackson Citation1996). However, in some cultural contexts, women may not seek such individualisation, or may face a backlash when they do. Should this goal of individualisation, therefore, be removed in contexts where individualisation is not sought or effective? To answer this question, it is important to point out two different reasons for why women might not want to move to a more individual orientation. First, women may make the choice to conform to existing community norms and practices out of fear of possible penalties for not doing so. Participation in microfinance programmes, for instance, has been associated with increased experience of verbal and physical violence by women in Bangladesh (Rahman Citation1999). There is also evidence from gender-sensitive health research (Mumtaz and Salway Citation2009; Safi and Doneys Citation2019; Thapa and Niehof Citation2013) to show that, in certain cultural contexts with more strict gender norms, a focus on autonomy can have a detrimental impact on women’s access to health services. In a context where culture and social norms put a great deal of importance on social ties, autonomy may not be enough to produce positive changes and in fact may go against encouraging forms of social support that are key to women’s greater access to reproductive healthcare (Safi and Doneys Citation2019). Second, women may not view the pursuit of more independence, such as, for example, in the form of financial autonomy, as a desirable objective (Doneys, Doane, and Norm Citation2020). This can be the case in contexts were family togetherness is highly valued (Kabeer Citation1999). Given that such contextual differences are understood, knowledge of local definitions of empowerment can help to design programmes to empower women in an effective manner, which avoids unintended negative consequences on beneficiaries and does neither underestimate nor overestimate the extent to which women realise new possibilities as a result of empowerment interventions.

However, information on women’s own definitions of empowerment is rare, as are scientific publications on this topic. Only a few studies have investigated the relative importance of different empowerment dimensions in specific contexts using small-scale, qualitative techniques. All these studies did this as a pre-step to construct an empowerment measure for a subsequent measurement of the level of women’s empowerment in their particular context. Parveen (Citation2005), for instance, conducted a focus group discussion with 12 women in rural Bangladesh to determine the relative weight that each of six pre-specified indicators of empowerment would be assigned to for the calculation of a composite index of empowerment. Legovini (Citation2005) used in-depth interviews with 80 key informants to understand perceptions of empowerment by poor local women in Ethiopia and identify suitable empowerment indicators for a subsequent empowerment assessment. Hashemi, Schuler, and Riley (Citation1996) investigated local meanings of empowerment in the context of six villages in Bangladesh through extensive observation and personal interviews in order to develop relevant measures of empowerment. Jupp, Ibn Ali, and Barahona (Citation2010) used a qualitative self-assessment to let women in Bangladesh set their own indicators of empowerment. While these studies are excellent for providing information about relevant definitions of empowerment in very specific, small local contexts, larger-scale quantitative evidence of women’s own understanding of empowerment in different countries is currently lacking.

Therefore, this study aims to provide a quantitative assessment of women’s own understanding of empowerment in three purposively selected countries: Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. These three Southeast Asian countries are all located in relatively close proximity, but differ in their level of development and cultural views of gender roles. We investigate socio-demographic correlates of women’s definitions of empowerment as women’s views might not only differ between but also within countries. In addition to directly asking women what empowerment means to them, we also obtained information on women’s perception of the positive effects of empowerment projects in which they had participated.

Methods

The study uses individual-level data obtained from the research project “What is Essential is Invisible: Empowerment and Security in Economic Projects for Low-Income Women in Four Mekong Countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam)”, the main goal of which was to assess empowerment from development projects in Southeast Asia that had the explicit goal of empowering low-income women. The project started with qualitative research that inquired into the meaning of empowerment for project participants and whether the empowerment as defined by them was experienced (Doane and Doneys Citation2015; Doneys, Doane, and Norm Citation2020). However, different from other studies, the qualitative data were furthermore used to design a set of closed-ended, multiple-choice questions on women’s own definitions of empowerment, which were used in a subsequent quantitative survey. This allowed for the assessment of local perceptions of the meaning of empowerment on a larger scale than the initial qualitative approach. For instance, the qualitative data strongly indicated that empowerment was often understood in relational terms, as the ability to contribute to a group and, in return, the respect and social recognition one receives from others.

Our analysis draws on this quantitative survey that was conducted among 1,210 women in Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam in 2016 who were participants in development projects aimed at empowering women. In the statistical analysis, the number of observations was reduced to 962 respondents due to missing values in some of the variables. Convenience sampling was used to select the respondents based upon the following criteria: (1) low-income status; (2) participation in empowerment activities; and (3) accessibility. We acknowledge that our convenience sampling approach may allow for possible selection bias and that the results of our analysis may not be fully generalisable. The first two sample selection criteria were applied to ensure that the women were in need of economic or social assistance and, by the time of the survey, had participated in one or more empowerment activities, and could, thus, provide information about their respective experiences. The third criterion aimed at facilitating the survey. In each country, respondents were identified through lists of participants provided by institutions that organise empowerment activities, and, where necessary, through additional snowball sampling. Empowerment activities included a wide variety of efforts addressing economic issues (e.g. providing loans to women, setting up saving groups, and organising livelihood-related training and activities) or women’s need for social support (e.g. through training on domestic violence prevention and helping women learn to negotiate and work with authorities for security-related interventions). Both local and international organisations arranged these activities. To obtain access to their projects we assured these organisations that the research was not an evaluation of their activities and that we would not mention their names or projects in publications. The survey was conducted in five provinces in Laos (Oudomxay, Vientiane, Phongsaly, Sekong, and Attapeu), four regions in Myanmar (the Dry Zone and the states of Kachin, Mon and Rakhine) and five regions in Vietnam (the city of Hanoi and the provinces of Dien Bien, Hoa Binh, Ninh Binh and Thanh Hoa).

Interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire that included questions on women’s general understanding of empowerment and their perception of it as an outcome of empowerment activities in which they had participated. Moreover, the questionnaire captured a range of socio-economic characteristics. Women’s general understanding of empowerment was measured through a closed-ended question that provided answer options derived from the qualitative survey results. Women’s perception of empowerment as an outcome of projects in which they had participated was measured by a series of questions that focused on different levels of impact. After prompting respondents to recall the activity which had the most positive impact on (i) them as an individual, (ii) their family, (iii) the respective group of project participants, and (iv) their community, respondents were asked to specify these impacts separately in closed-ended questions, the answer options of which, again, were based on findings from the previous qualitative survey. For instance, the importance of knowledge, contributing to a social group, or gaining respect and recognition from others, were all themes that emerged clearly from the qualitative data.

Socio-economic characteristics of the interviewed women were measured through questions on their age, education, marital status, maternal status, and contribution to total household income. Information on women’s ethnicity was collected and an ethnic minority dummy variable constructed by grouping the respective ethnic minorities in each country together. Ethnic minorities comprised of non-Lao Loum respondents in Laos, non-Bamar respondents in Myanmar and non-Kinh respondents in Vietnam. It is important to note that these ethnic minorities included women belonging to diverse ethnic groups, such as Brao, Khmu and Phunoi people in Laos, Kachin, Rakhine and Rohingya people in Myanmar, as well as Muong and Tai people in Vietnam. The ethnic minority dummy variable treats these different minorities as a homogeneous group, and allows comparison of them to the majority in each country. Possible differences within these minorities were not investigated due to the insufficient size of the sub-samples. Further characteristics were measured at the household level, including wealth and whether or not the women’s household was indebted and included disabled household members. The measure of household wealth was constructed based on questions about tangible asset ownership and housing conditions using principal components analysis.

The data were analysed using descriptive, univariate statistics in order to investigate women’s general understanding of empowerment and their perception of it as an outcome of development projects. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to identify socio-economic determinants of specific understandings of empowerment. The estimated regression models separately analyse which factors are correlated with answers to the following question “What does empowerment mean to you?”: (i) “being able to speak at meetings”, (ii) “having more knowledge”, (iii) “being able to express opinion”, (iv) “having more mobility”, (v) “being more independent”, (vi) “being more confident”, (vii) “having a greater say in household affairs”, (viii) “being respected by others”, (ix) “being able to support family” and (x) “making more money”. We should note, as a limitation, that these survey answers can be understood differently by the participants but they indicate broad patterns in terms of empowerment conceived more as an individual and/or as a relational process, which is what we were examining.

Results

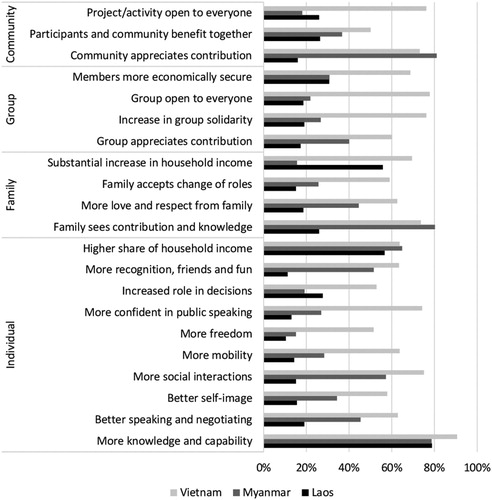

A comparison of the share of women who associated the term empowerment with specific meanings between the three countries is presented in . Results indicate that respondents from Vietnam, overall, had a more diverse understanding of empowerment than women in Myanmar and Laos. Each of the possible meanings of empowerment was selected by at least half of the Vietnamese sample, whereas some interpretations were only chosen by a small minority of respondents from Myanmar and Laos.

Figure 1. Share of respondents who associate the term “empowerment” with specific meanings, by country (Vietnam: n = 361; Myanmar: n = 370; Laos: n = 231).

The most common understanding of empowerment among women respondents from Vietnam was “having more confidence” (chosen by about 85% of respondents), followed by “having more knowledge” (75%). In Myanmar, most respondents interpreted empowerment as “having more knowledge” (79%), while “being able to support family” (59%) was the second-most frequently selected answer. Women respondents in Laos predominantly viewed empowerment as “being able to support family” (59%), followed by “making more money” (52%). Overall, three interpretations stand out: “being able to support family” was the only meaning of empowerment selected by at least 59% of respondents in all three countries, followed by “making more money” which was chosen by at least 52%. “Having more knowledge” was the only interpretation chosen by at least 75% of women in two countries (Vietnam and Myanmar), while being selected by 37% of respondents in Laos.

With regard to understandings of empowerment that may be interpreted as having more autonomy and having a “voice”, relatively few women in Laos and Myanmar interpreted empowerment as “being able to talk freely with partner” (less than 10% in Laos and Myanmar), “having more mobility” (7% in Laos and 24% in Myanmar), “being able to express opinion” (17% in Laos and 29% in Myanmar), “having a greater say in household” (less than 30% in Laos and Myanmar) and “being able to speak at meeting” (9% in Laos and 37% in Myanmar). Slightly more women in Laos and Myanmar flagged “having more independence” (30–50%) and “having more confidence” (40–50%) as an element of empowerment.

Parameter estimates from the logistic regression models of different understandings of empowerment are shown in and . Descriptive statistics of all variables used in the regression models are given in the Appendix. Women from households that were fairly well-off, relative to the households of other respondents in our sample of low-income women, were significantly less likely to understand empowerment as “having more knowledge” and “being able to support family”, while a significant positive relationship between higher quintiles and understanding empowerment as “being more confident” was identified.

Table 1. Parameter estimates from logistic regressions of understanding of empowerment – Part I (n = 962).

Table 2. Parameter estimates from logistic regressions of understanding of empowerment – Part II (n = 962).

Moreover, older women had a higher probability of mentioning any of the given interpretations of empowerment, indicated by the positive and statistically significant age coefficient, except for understanding empowerment as “making more money”. Among very old women, though, this positive effect was significantly smaller, as indicated by the negative and statistically significant age squared coefficient, again except for understanding empowerment as “being able to make more money”.

With regard to the effect of education, our estimates show that women with higher educational attainment were more likely to flag a number of aspects as constituents of empowerment. In particular, women who attended at least high school were more likely to agree with any of the given interpretations of empowerment than women without any formal education, except for understanding empowerment as “making more money” for which no difference between these two groups of women is indicated. Moreover, women whose highest educational attainment was middle school had a higher probability of mentioning any of the given interpretations of empowerment than women without any formal education, except for understanding empowerment as “making more money” and “being able to support family” for which no difference between these two groups of women is indicated. Women whose highest educational attainment was elementary school were more likely to understand empowerment as “being able to speak at meetings”, “having more knowledge”, “having more mobility”, “being more independent”, “having a greater say in household affairs”, “being respected by others” and “being able to support family” than women without any formal education.

Furthermore, women with a partner were less likely to see empowerment as “being able to speak at meetings”, “being more independent” and “being more confident”, while women with children had a lower probability to perceive “being able to express opinion” as an element of empowerment. The effect of belonging to the ethnic majority in their respective country on women’s understandings of empowerment was positive with regard to “being able to speak at meetings”, “having more knowledge”, “having more mobility”, “being more independent” and “being more confident”, while negative regarding “being able to support family”.

Women’s economic power within their own household, their earning position relative to other household members, was positively associated with various understandings of empowerment. In particular, women who were main earners in their household were more likely to flag “being able to speak at meetings”, “being able to express opinion”, “being more independent”, “having a greater say in household affairs”, “being able to support family” and “making more money” as signs of empowerment than women who did not contribute to their household’s income at all. Moreover, women who earned income, but less than the main earner in their household, had a higher probability to understand “being able to express opinion”, “having a greater say in household affairs”, “being able to support family” and “making more money” as empowerment than women who did not generate any income at all.

Last but not least, regional differences were revealed, with women from Myanmar and Laos being less likely to agree with any of the given interpretations of empowerment than women from Vietnam, except for understanding empowerment as “being able to support family”, for which no significant country effect could be identified, and “having more knowledge”, which was only less likely to be mentioned by women from Laos.

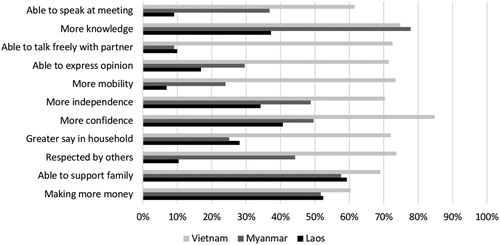

compares the share of women who perceived specific positive effects of participating in empowerment activities. It shows that having more knowledge was the most frequently experienced positive effect at the individual level in all three countries (reported by 79% of respondents in Laos and Myanmar, and 91% in Vietnam). Earning a higher share of household income was stated as a positive effect by the majority of women in Laos (57%), Myanmar (65%) and Vietnam (64%). At the family level, the majority of women in Myanmar (80%) and Vietnam (74%) reported that their family sees their contribution and knowledge as a positive consequence of participating in empowerment activities. A substantial increase in household income was also experienced as a positive effect by most women in Laos (56%) and Vietnam (70%). At the community level, a vast majority of women in Myanmar (81%) and Vietnam (73%) reported the appreciation of their contribution by their community as a positive outcome of participating in empowerment activities. A range of further positive effects at different levels were experienced by women as can be seen in . Overall, women in Vietnam experienced a wider range of positive effects than women in Myanmar and Laos, in particular effects at the group level, but also at the individual, family and community level.

Discussion

Our results indicate important discrepancies between countries in terms of women’s understandings of empowerment. In particular, we found that women in Laos and Myanmar had narrower understandings of empowerment than women in Vietnam. Understandings of empowerment that may be interpreted as having more autonomy and having a “voice” were shared by relatively few women in Laos and Myanmar as compared to women in Vietnam. Despite these differences, women in all three countries had a number of similar notions. A majority of women in Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam saw the “ability to support the family” or “making more money” as forms of empowerment. Overall, however, our findings are in line with our earlier discussion of the contextuality of empowerment. It is noteworthy, though, that the relative importance of specific understandings of empowerment in different countries, in terms of how often they were mentioned compared to other understandings, might to some extent be influenced by the nature of empowerment activities offered in these places. For instance, the high number of women in Myanmar and Vietnam who stated that empowerment means having more knowledge could be partly due to the fact that many empowerment projects in which they participated focused on income-generating activities and taught participants skills needed to design, produce and market their goods.

Moreover, our results show substantial variation among countries in terms of women’s actual experience of positive effects of empowerment activities on their life. Overall, positive effects were felt at the individual level, but also at the family, group and community level, as women valued their newly acquired ability to support their family and community, and the acknowledgement of their contributions. These findings are in line with the outcome of earlier studies that have pointed to the relevance of broader, social ideas of empowerment that emphasise partner relationships as well as the relationship of a women’s sense of empowerment to family and community welfare as opposed to narrower definitions of empowerment as voice and autonomy only (Doane and Doneys Citation2015; Porter Citation2013). However, not all women experienced positive effects of empowerment activities equally. For instance, accounts of positive effects at the family level in the form of acceptance and appreciation by other family members were noticeably rare among women in Laos. Moreover, only a small minority of women in Laos and Myanmar reported to have experienced more freedom and mobility, as well as an increased role in decision-making as a result of participating in empowerment projects. Some discrepancies between women’s understandings of empowerment and the actual positive effects of empowerment projects could be observed. For example, a majority of women in Myanmar viewed “making more money” and “being able to support family” as empowerment, while only a small share of women in Myanmar experienced a substantial increase in total household income. Despite the aforementioned differences in positive effects of empowerment projects between countries, women in all three countries shared some experiences. Positive effects that were experienced by a majority of women in all three countries were limited to increased knowledge, improved capabilities and a higher share of household income. Overall, these findings suggest shortcomings of empowerment projects in terms of empowering women in a multifaceted way and further emphasise the need for a better understanding of the needs of project beneficiaries.

We also found that women’s views of empowerment can be partially explained by socio-economic factors as well as cultural and regional differences. Regarding the association of household wealth and women’s understanding of empowerment, our results show some interesting patterns. Much of the literature on women’s attitudes toward gender roles suggests lower levels of affluence to be associated with more traditional gender role attitudes (Akcinar Citation2018), and hence possibly narrower understandings of empowerment. However, our results show that women from different wealth quintiles did not differ significantly in terms of most understandings of empowerment, except for the finding that women from relatively well-off households were more likely to perceive empowerment as having more confidence, and a greater tendency among women from poorer households to identify the acquisition of new knowledge and the ability to support their own family as elements of empowerment. This suggests that women from poorer backgrounds do not have a narrower, but rather a different understanding of empowerment – one that might have been shaped by their most immediate needs.

In addition to household-level wealth, we found that women’s individual earning position within their families is positively associated with the probability that women identified a range of abilities, achievements and freedoms as elements of empowerment. This is in line with the view that as women’s economic power within their families increases, in many cultural contexts more egalitarian attitudes are expected to be held by both female and male household members (Akcinar Citation2018), which is likely to expand women’s perception of what empowerment should look like.

Perhaps related to the previous point, our findings suggest that both having a partner and having children were negatively related to a number of specific understandings of empowerment. While income contribution tends to be associated with a more individual emphasis on the perception of empowerment, women in more traditional roles as wife or mother may think more in collective and familial terms.

Furthermore, according to our estimates, middle-aged women were more likely to associate empowerment with a wide range of understandings than their younger and older counterparts, who expressed more narrow perceptions of empowerment. Cohort effects might have contributed to this relationship, as these are often confounded with the impact of age (Lynott and McCandless Citation2000). Over recent decades, cohorts of women have developed less traditional gender role attitudes (Boehnke Citation2011), which may explain our finding that older women had less varied understandings of empowerment than middle-aged women. We can only speculate, though, about our findings that younger women also had less varied understandings of empowerment than middle-aged women. It might be that younger women had not yet developed a broad awareness of different elements of empowerment that goes beyond equality in terms of the ability to earn money. Younger women, in the early stages of their marriage, might also be struggling with the need to financially support their family and, as a result, emphasise income-related aspects of empowerment.

We also found ethnicity and country effects on women’s understanding of empowerment. Interestingly, belonging to the ethnic majority in a country, increased the probability that women flagged different individual abilities, achievements and freedoms as signs of empowerment, except for the understanding of empowerment as being able to support their own family, which was more likely to be shared by women belonging to ethnic minorities. Knowledge and gender norms are often different among ethnic minorities compared to the ethnic majority in Southeast Asian countries (UNFPA Citation2007). Moreover, women from Vietnam showed broader understandings of empowerment than their counterparts from Myanmar or Laos, which is in line with the general notion that women’s empowerment has been particularly strong in Vietnam as compared to other countries in the region (World Bank Citation2011). As a result, and due to the fact that the word “empowerment” has been used widely by the Vietnam Women’s Union, women in Vietnam might be more aware of the various elements of empowerment. Country-level differences may also depend on local gender norms and on the women’s social and work lives. According to the qualitative analysis of Doneys, Doane, and Norm (Citation2020), knowledge, for instance, is particularly important for women involved in trading products requiring updated design and higher quality to be marketable.

Our finding of the strong positive correlation between women’s educational attainment and their understandings of empowerment is consistent with the predominant evidence that women with a relatively high level of formal education also tend to have more egalitarian attitudes (Akotia and Anum Citation2012; Brewster and Padavic Citation2000; Kulik Citation2002), and thus might have a broader view of what constitutes empowerment.

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate that women’s ideas of empowerment differ according to their cultural, economic and social contexts. This highlights the importance of thorough initial assessments of understandings of empowerment of intended beneficiaries when planning projects aimed at strengthening women’s empowerment. As Doane and Doneys (Citation2015) point out, institutions that provide support to women frequently fail to do so in a sustainable way because of their narrow, predetermined “outsider” views of empowerment which are often at odds with the perspectives or immediate needs of local participants. Popular concepts of empowerment, in particular those adopted by international organisations, frequently emphasise women’s economic independence while neglecting other aspects (Doane and Doneys Citation2015; Porter Citation2013). Our findings suggest that empowerment strategies should be customised to local contexts rather than depend exclusively on imported and generic strategies. This does not mean prioritising social values that justify keeping women in a subordinate role through oppression and fear. Instead, it means that, to help women break free of stereotypes and overcome challenges, empowerment measures must take into account what women prioritise in an environment with context-specific barriers and opportunities. Knowing women’s own definitions of empowerment, and how context-specific this understanding may be, will help to minimise the potential unintended negative effects of more generic outside interventions. It will also enable development practitioners to understand situations when local women’s own aspirations and priorities differ from the target priorities of external institutions that want to empower them. This is key to developing solutions that are effective and sustainable. Beyond a more thorough assessment of women’s priorities from outside, directly involving local women in the planning of empowerment interventions will help to bridge the gap between external development actors and their intended beneficiaries, while providing additional opportunities for growth for those involved in the planning process.

Acknowledgements

We thank our project sponsor, Australian Aid, and team members: Donna Doane, Duanghathai Buranajaroenkij, Phuong Ha Pham, Hieu Dinh Minh, Nguyen Phuong Chi, May Sabe Phyu, Nang Phyu Phyu Lin, Sanda Thant, Khin Zar Naing, Soutthanome Keola, Kanokphan Jongjarb, Norm Sina, Christine Widjaya, and Jhozine Damaso.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marc Völker

Marc Völker is Assistant Professor at the Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University, Thailand. His research focuses on environment and development in South-east Asia and beyond.

Philippe Doneys

Philippe Doneys is Associate Professor in Gender and Development Studies at the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) in Bangkok, Thailand. He is a political sociologist with a focus on South-east Asia.

References

- Akcinar, B. 2018. “Gender Role Attitudes and its Determinants for Women in Turkey.” In Current Debates in Gender and Cultural Studies, edited by G. T. Gecgin, 37–47. London: IJOPEC Publication.

- Akotia, C. S., and A. Anum. 2012. “The Moderating Effects of Age and Education on Gender Differences on Gender Role Perceptions.” Gender and Behaviour 10 (2): 5022–5043.

- Boehnke, M. 2011. “Gender Role Attitudes Around the Globe: Egalitarian vs. Traditional Views.” Asian Journal of Social Science 39 (1): 57–74.

- Brewster, K. L., and I. Padavic. 2000. “Change in Gender-Ideology, 1977–1996: The Contributions of Intracohort Change and Population Turnover.” Journal of Marriage and Family 62 (2): 477–487.

- Calvès, A.-E. 2009. “Empowerment: Généalogie d’un concept clé du discours contemporain sur le développement.” Revue Tiers Monde 4: 735–749.

- Doane, D., and P. Doneys. 2015. “Lost in Translation? Gender and Economic Empowerment in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region.” In Gendered Entanglements: Revisiting Gender in Rapidly Changing Asia, edited by R. Lund, P. Doneys, and B. P. Resurreccion, 69–96. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- Doneys, P., D. Doane, and S. Norm. 2020. “Seeing Empowerment as Relational: Lessons From Women Participating in Development Projects in Cambodia.” Development in Practice 30 (2): 268–280.

- FAO. 2015. Empowering Rural Women Through Social Protection, Rural Transformations – Technical Papers Series #2. Rome: FAO.

- Fierlbeck, K. 1995. “Getting Representation Right for Women in Development: Accountability, Consent, and the Articulation of Women’s Interests.” IDS Bulletin 26 (3): 23–30.

- Hashemi, S. M., S. R. Schuler, and A. P. Riley. 1996. “Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh.” World Development 24 (4): 635–653.

- Jackson, C. 1996. “Rescuing Gender From the Poverty Trap.” World Development 24 (3): 489–504.

- Jupp, D., S. Ibn Ali, and C. Barahona. 2010. “Measuring Empowerment. Ask Them: Quantifying Qualitative Outcomes From People’s own Analysis.” SIDA Studies in Evaluation 2010 (1): 1–99.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464.

- Kulik, L. 2002. “The Impact of Social Background on Gender-Role Ideology: Parents’ Versus Children’s Attitudes.” Journal of Family Issues 23 (1): 53–73.

- Ladič, M. 2015. “Listening to the Subaltern in Rwanda: Bottom-Up Gender Perspectives on Development Concepts.” Analele Universităţii din Bucureşti. Seria Ştiinţe Politice 17 (2): 164–180.

- Legovini, A. 2005. Measuring Women’s Empowerment and the Impact of Ethiopia’s Women’s Development Initiatives Project. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Lynott, P. P., and N. J. McCandless. 2000. “The Impact of Age vs. Life Experience on the Gender Role Attitudes of Women in Different Cohorts.” Journal of Women & AAing 12 (1-2): 5–21.

- Malhotra, A., and S. R. Schuler. 2005. “Women’s Empowerment as a Variable in International Development.” Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives 1 (1): 71–88.

- Meinzen-Dick, R. S., D. Rubin, M. Elias, A. Abenakyo Mulema, and E. Myers. 2019. “Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture: Lessons from Qualitative Research.” IFPRI Discussion Paper. Washington, DC.

- Mumtaz, Z., and S. Salway. 2009. “Understanding Gendered Influences on Women’s Reproductive Health in Pakistan: Moving Beyond the Autonomy Paradigm.” Social Science & Medicine 68 (7): 1349–1356.

- O’Hara, C., and F. Clement. 2018. “Power as Agency: A Critical Reflection on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment in the Development Sector.” World Development 106: 111–123.

- Parveen, S. 2005. “Empowerment of Rural Women in Bangladesh: A Household Level Analysis.” In Farming and Rural Systems Economics, Vol. 72, edited by W. Doppler, and S. Bauer, 1–226. Weikersheim: Margraf.

- Porter, E. 2013. “Rethinking Women’s Empowerment.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 8 (1): 1–14.

- Rahman, A. 1999. “Micro-credit Initiatives for Equitable and Sustainable Development: who Pays?” World Development 27 (1): 67–82.

- Safi, F. A., and P. Doneys. 2019. “Exploring the Influence of Family level and Socio-demographic Factors on Women’s Decision-making Ability Over Access to Reproductive Health Care Services in Balkh Province, Afghanistan.” Health Care for Women International 41 (7): 833–852

- Thapa, D. K., and A. Niehof. 2013. “Women’s Autonomy and Husbands’ Involvement in Maternal Health Care in Nepal.” Social Science & Medicine 93: 1–10.

- UNFPA. 2007. Knowledge and Behaviour of Ethnic Minorities on Reproductive Health. Hanoi: UNFPA Vietnam.

- UNFPA. 2019. State of the World Population 2019. New York: UNFPA.

- United Nations. 2015. Gender Equality in Human Development – Measurement Revisited. Geneva: United Nations Human Development Report Office.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. 2002. Commission on the Status of Women: Report on the forty-sixth session (4-15 and 25 March 2002). Official Records, 2002. Supplement No. 7 (E/2002/27-E/CN.6/2002/13). New York: United Nations.

- World Bank. 2011. Vietnam – Country Gender Assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank.