ABSTRACT

Mozambican law recommends community councils to promote the co-management of natural resources in protected areas. In the Limpopo National Park, the park committee has served as the community council for the last two decades. Based on fieldwork conducted in 2009–2019, this practical note identifies challenges that the committee faces and suggests two pathways to tackle the challenges: the committee members should be selected based on individual capacity; and financial resources must be directed towards developing their capacity. Further research on how to establish these pathways are imperative to enable the committee members to focus on activities for the co-management.

Introduction

The incremental increase in protected areas, as mandated by the international community (CBD Citation2010) and the pursuit of “double sustainability” to simultaneously protect biodiversity and people's livelihoods (Cernea and Schmidt-Soltau Citation2006) have led the protected area administrators to involve local residents in the co-management of natural resources and promote community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) (Mahanjan et al. Citation2020). Scholars and practitioners argue that, for the successful co-management, community members must have a strong sense of ownership of the natural resources and be involved in decision making as equal partners of the governmental and non-governmental actors (Maeshan and Lumbasi Citation2013; Roka et al. Citation2019).

In Mozambique, CBNRM began to be implemented in the mid-1996 at a modest scale (Kube Citation2005). It became widely popularised, as the article 95 of the 1999 Forest and Wildlife Law gave a legislative context for the creation of community councils (Conselhos Comunitários) to facilitate the co-management. However, after nearly two decades, little is known about whether these councils could realise the successful natural resource co-management. In this practical note, we analyse challenges faced by the community council in the Limpopo National Park (LNP) in southwestern Mozambique. In the LNP, the park committee was established as the community council. We show how the committee faces challenges to represent the residents and negotiate with the park administration to make informed decisions concerning co-management. We aim to outline potential pathways to tackle these challenges.

Methodology

The case study area: Limpopo National Park

The LNP was established in 2001 as a part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP) (Decree 38/2001) that consists of South Africa's Kruger National Park and Zimbabwe's Gonarezhou National Park. Together with surrounding game reserves, the GLTP forms one of the largest protected areas in southern Africa (Wolmer Citation2003). The South Africa's Peace Parks Foundation and the German Development Bank (KfW) financially sponsor the GLTP, and the National Conservation Agency (ANAC) of Mozambique, under the Ministry of Land, Environment, and Rural Development (MITADER), currently manages the LNP.

By including the LNP into the GLTP, the donors and the Mozambican government have hoped to promote nature conservation and local socioeconomic development, primarily based on tourism (Ntuli et al. Citation2019). The actual promotion led to, on the one hand, a highly controversial conservation-induced resettlement of 7,000 residents displaced from the LNP (Lunstrum Citation2016; Otsuki, Achá, and Wijnhoud Citation2017; Witter and Satterfield Citation2019).Footnote1 On the other, a buffer zone around the park was created in which 20,000 people were allowed to co-manage the LNP's natural resources (Givá and Ration Citation2017). This practical note focuses on experiences of the residents in this buffer zone where they are mostly engaged in maize and livestock farming.

We should note here that, traditionally, the residents actively hunted game, but this became illegal when the LNP was established (José Citation2017). Therefore, the co-management projects in the LNP in practice focus on development of sustainable farming and related income generation activities. To acquire and manage the co-management projects through the legally recommended community council, civil society organisations: Associação Rural de Ajuda Mútua (ORAM) and Comité Ecuménico para o Desenvolvimento (CEDES) began to assist the LNP residents in 2002 with legalisation of the park committee as the LNP's community council.

Fieldwork

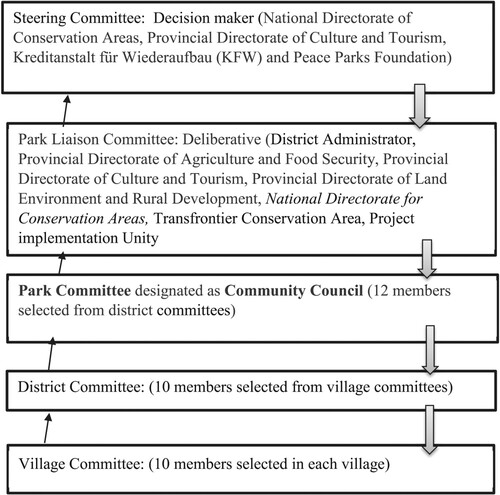

This note is based on fieldwork conducted intermittently between 2009 and 2019 as a part of the lead author's master and doctorate research on natural resource management in the LNP. First, interviews were conducted with the LNP administrator and representatives of ORAM and CEDES that helped the legalisation of the park committee. Second, in three districts that are a part of the LNP, the lead author conducted interviews and focus group discussions with members of the park committee, which consist of representatives of district and village committees (). More specifically, 18 village committee members, 12 district committee members, 4 park committee members; and 55 heads of households who are not members of these committees were interviewed to clarify their views on committees’ works and challenges they face. Twenty-five people formed the focus group in each district, mostly women, because men were away in search of work opportunities in South Africa (cf. Norman Citation2005). The lead author took notes of the interviews and discussions in order to establish patterns of information emerging from them. The result section below summarises the patterns as identified challenges faced by the park committee.

Results

The LNP's co-management structure

outlines the structure of the LNP's co-management. The steering committee includes members from ANAC, Peace Parks Foundation, KfW, and the Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. Under the steering committee, there is a park liaison committee, which functions as a bridge between the steering committee and the park committee (MITUR Citation2012).

Selection of the committee members

According to the informants, the park administration first communicated to the residents that the park committee could be their community council in 2001. The officers instructed the residents to select representatives from their villages to participate in the village and district committees from which the park committee members would be selected. For the village committee, the villagers collectively selected their representatives with the support from the civil society organisations.

The law states that village committee members should be village leaders or traditional authorities, which means that all committee members have other responsibilities in their villages. As one member said:

It is not common to have committee members with only one responsibility. Most members are politicians and belong to various organisations, such as the Mozambican Women's Organisation, or they are teachers, religious leaders or hold prominent positions in the village.

At the district level, committee members generally do not know the rationale for their committees. As one interviewee said: “We received instructions from the park administration to choose two people from the village committee to take part in the district committee, without knowing for what purpose.” This shows that, from its inception, the committees have been largely directed by the park administration. This dependency leads to the following challenges for the committees to design and operationalise their initiatives for the co-management of natural resources in the LNP.

Challenges faced by the park committee

Lack of clarity about the committee's responsibilities

The legal framework defines the community council's responsibilities as: (a) sustainable resource management; (b) development project management; (c) adjustment of local rules of nature conservation to updated legislations; (d) collaboration with neighbouring villages for resource management; (e) information sharing and updating; and (f) holding regular meetings to ensure the planning of activities and accountability to the residents (Decree 89/2017). However, majority of the park committee members did not have a clear idea about their responsibilities. One interviewed park committee member in fact had no idea about what was expected from them. Likewise, whilst 34% of district committee members and 25% of village committee members were aware of some of their responsibilities, most of them were unclear about the activities they should undertake to fulfil their responsibilities.

The park committee's dependency on the park administration

The absence of clarity about the committee's responsibilities stems from the lack of planning activities. At the village level, members stated that they only undertook ad hoc tasks instructed by the district and park committees. At the district level, all members mentioned the existence of management plans, but the plans were not operationalised due to a lack of transport to attend meetings. The park committee members also said that their plans were not being fulfilled due to the lack of transport.

The lack of planning, especially at the level of village committees, shows that the base structure of the park committee only functions to operationalise external agendas. In addition, the committees’ dependency on the park administration for transport to meetings reduces their capacity of self-determination and sense of ownership. Since the committee members cannot actively convene meetings, they had different understandings of how often they meet. The meetings seemingly take place 3–6 times a year.

Consequently, the committees end up prioritising the activities defined by the park administration. This leads to the awkward relationship between the park committee and the park administration. Most of the park committee members said that their relationship with the park administration was not very good and all the district and village committee members stated that their relationships with the park administration were “bad.” The committee members felt so dependent on the park administration that they only served the interests of the park administration rather than their villages. The shortage of resources, in particular the means of transport hinders the implementation of the committee’ initiatives.

Absence of community benefits

Reflecting the park committee's dependency on the park administration, park residents consider the benefits they receive from co-management as mostly a gift from the park administration. By 2017, some villages had received their share of benefits but struggled to use them for a common good. For example, the district of Mabalane installed a maize milling machine. However, the mill could not operate due to a lack of funds to purchase fuel. The interviewees said that the mill was built too far away for many people and it would not be very useful even if it were to operate. A majority of the villagers were not involved in deciding on the location of the mill.

Other villages in the LNP had expected to purchase motorised pumps for irrigation or to invest in tourism development as a result of their participation in the co-management projects. The expectations created frustration since no substantial funds have become available. For example, safari and ecotourism for local economic development was the rationale for the LNP's establishment in the first place. However, the number of tourists has been far lower than projected. The weak tourism development affects other commercial activities. Even if it were developed sufficiently, the park administration did not have any plans to train the residents to become the managers of their tourism projects.

Therefore many residents see no community benefits of the co-management. They only experience the encroachment of wild animals that they can no longer hunt, even though the animals destroy their crops and attack their cattle.

Inability of the park committee to become accountable to residents at large

The inability to provide the park residents with the tangible and sustainable community benefits of co-management makes the committee members feel that they cannot properly solve problems identified at the village level. This situation results in “embarrassment” for the committee members because, for the residents at large, the inability is seen as a result of complicity between the committee and the park administration. As one member of the village committee pointed out, it is common for their villagers to say to the committee members: “Your elephants destroy our fields … ”

Likewise, for the park residents who still hunt wild animals on a small scale (even though it has been illegal), the role of the committees is also confusing. From their perspective, the committees are representatives of the park and not the villages. Some villagers genuinely believe that the committee members are guards of the park and not representatives of their interest. This distrust is a result of weak involvement of the residents in meetings and project planning.

The community's distrust of and dissatisfaction with the committees lead to the park committee's lack of accountability to the LNP residents at large. In meetings, the committee members discuss with residents the issues agreed or decided upon with the park administration, such as priorities for the community benefits and issues related to the human–wildlife conflict. Yet, as committee members and park residents are not sufficiently clear about the committees’ responsibilities and abilities, residents find it impossible to assess the park committee's performance and their accountability to them.

Need to develop the capacity of the committee members

The inability of the committee to be accountable for their villagers is rooted in the rather fundamental issue: low educational levels of the committee members. Nearly all the members have a level of schooling of between none and grade five. They have quite limited official Portuguese language skills. Only one interviewed member had completed grade eleven. Even those who had some literacy in Portuguese had lost some of their skills. According to one interviewee: “Over time we have lost some language skills due to lack of application of the knowledge.”

As the official language of the park administration is Portuguese, this situation limits the park committee members’ interaction with the park administration or the steering committee, whose members do not speak the local language, Xi-Changana. At some meetings, the translation from Portuguese into the local language is prioritised but is largely insufficient. Consequently, a majority of the committee members end up endorsing decisions made by those who understand Portuguese.

The lack of basic education is also a major problem among women. In 2005, changes in legislation led the community council to encourage the participation of women. Despite the government's efforts to include women, only 11% of the LNP park committee members, 27% of the district committee members and 28% of the village committee members are female. The participants confirmed that women generally do not have a strong voice and that male members do not encourage women's participation. According to one interviewee: “Women are not part of the committees because they do not speak out in the meetings.” Moreover, women are often too busy with domestic chores to participate in the committees’ activities.

Civil society organisations such as ORAM and CEDES have carried out training programmes to prepare community members for participation in the co-management. However, 25% of the interviewed park committee members, 33% of the district committee members and 42% of village committee members said that they had not participated in any training related to natural resource management. As the LNP borders South Africa, many committee members and park residents migrate seasonally to South Africa in search of work. The committees are thus constantly obliged to find replacement members, and new members fail to receive the training in a timely manner. In addition, the civil society organisations are often short of the funds and staff required to regularly provide training programmes. The steering committee for the co-management should pay more attention to the capacity development of park committee members who can pass on their knowledge on natural resource co-management to the wider resident community.

Conclusion

In this practical note, we have provided evidence that the ways the park committee is structured and operates in the LNP undermine the much needed local sense of ownership of natural resources and the co-management projects. They rather increased the committee's dependency on the park administration and led the park's residents to distrust the committee members who are supposed to represent their interests in the co-management. We argue that all the challenges faced by the park committee stem from a lack of the committee members’ capacity to start planning processes at the level of the village committees and to bring the residents’ concerns to the park administration's attention. In other words, the park committee seems to merely function as a messenger of the park administration's decisions rather than a messenger of the park residents’ concerns and needs.

We identify that the potential pathways to the committee members’ capacity development are twofold: First, the committee members should be selected according to their individual capacity to perform tasks pertaining to natural resource management rather than according to political positions or cultural conceptions such as gender roles. Second, the park administration should allocate an operational fund to each committee to keep on training the selected committee members to focus on income generating activities. The Mozambican law defines that 20% of a national park's income should be used to support development projects for communities within, as well as resettled from, the park. Instead of using the fund for ad hoc development projects, the park administration and donors should more consciously direct the fund to develop the capacity of skilled committee members.

More in-depth research is imperative to further specify how such allocation of funds for capacity development could be materialised in the current structural context of protected area governance in Mozambique. The success of the co-management in the LNP depends on the capacity of the park committee members who should be able to establish trust between local residents and external governmental and non-governmental actors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Esperança Rui Colua de Oliveira

Esperança Rui Colua de Oliveira is a PhD candidate in Department of Sociology at Eduardo Mondlane University in Mozambique. She holds a master's degree in Rural Sociology and Development Management at Eduardo Mondlane University. Her research is focused on community participation in natural resources co-management.

Kei Otsuki

Kei Otsuki is Associate Professor in International Development Studies at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. She previously worked at United Nations University in Tokyo, Wageningen University in the Netherlands and Federal University of Pará in Brazil. She currently leads research projects on development and conservation-induced displacement and resettlement in Mozambique.

Marlino Eugenio Mubai

Marlino Eugénio Mubai is a senior lecturer and chair of History Department at Eduardo Mondlane University in Mozambique. He holds a Ph.D. in African Environmental History from the University of Iowa in the USA and a Master's Degree in Heritage and Cultural Studies from the University of Pretoria in South Africa. His research experience includes the political ecology of warfare, land tenure and natural resources management, resilience and adaptation to both men-made and natural disasters.

Notes

1 The resettlement process has been protracted, and majority of the people still live within the LNP.

References

- CBD-Convention on Biological Diversity. 2010. Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Targets. Montreal: CBD.

- Cernea, M. M., and K. Schmidt-Soltau. 2006. “Poverty Risks and National Parks: Policy Issues in Conservation and Resettlement.” World Development 34: 1808–1830.

- Givá, A., and K. Ration. 2017. “Parks with People in Mozambique: Community Dynamic Response to Human-Elephant Conflicts at Limpopo National Park.” Journal of Southern Africa Studies 43: 1199–1214.

- José, P. L. 2017. “Conservation History, Hunting Policies and Practices in the South Western Mozambique Borderland in the 20th Century.” PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

- Kube, R. 2005. “First Experiences of Community-Based Management Natural Resources Management Programme in Northern Mozambique.” Development in Practice 15: 100–105.

- Lunstrum, E. 2016. “Green Grabs, Land Grabs and the Spatiality of Displacement: Eviction from Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park.” Area 48: 142–152.

- Maeshan, T. G., and J. A. Lumbasi. 2013. “Success Factors for Community-Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM): Lessons from Kenya and Australia.” Environmental Management 52: 649–659.

- Mahanjan, S. L., A. Jagadish, L. Glew, A. Ahmadia, and M. B. Mascia. 2020. “A Theory-Based Framework for Understanding the Establishment, Persistence, and Diffusion of Comunity-Based Conservation.” Conservation Science and Practice 3: e299. doi:10.1111/csp2.299.

- MITUR – Ministry of Tourism. 2012. “Parque Nacional do Limpopo: Plano de Maneio e Desenvolvimento da Zona Tampão.” Accessed November 16, 2020. http://www.biofund.org.mz/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1548231053-PNL%20-%20Buffer%20Zone%20Management%20Plan%20-%20Proposed%20Final%20-%20June%202012.pdf.

- Norman, W. O. 2005. “Living on the Frontline: Politics, Migration and Transfrontier Conservation in the Mozambican Villages of the Mozambique-South Africa Borderland.” PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

- Ntuli, H., A. Sundström, M. Sjöstedt, E. Muchapondwa, and L. Amanda. 2019. “Understanding the Drivers of Subsistence Poaching in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area: What Matters for Community Wildlife Conservation?” ERSA Working Paper 796.

- Otsuki, K., D. Achá, and J. D. Wijnhoud. 2017. “After the Consent: Re-Imagining Participatory Land Governance in Massingir, Mozambique.” Geoforum 83: 153–163.

- Roka, K., W. Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, P. Özuyar, and T. Wall. 2019. “Community-Based Natural Resources Management.” In Life on Land: Encyclopaedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 161–174. Cham: Springer.

- Witter, R., and T. Satterfield. 2019. “Rhino Poaching and the ‘Slow Violence’ of Conservation-Related Resettlement in Mozambique Limpopo National Park.” Geoforum 101: 275–284.

- Wolmer, W. 2003. “Transboundary Conservation: The Politics of Ecological Integrity in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park.” Journal of Southern African Studies 29: 261–278.