?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We assessed barriers and opportunities for youth engagement in agribusiness. Results show that the majority of youth were engaged in agricultural production, especially in Zambia, while in Vietnam, they engaged in more diversified agricultural activities including input supply, transportation and advisory services delivery. Perceptions regarding the agricultural sector showed significant (P < 0.01) negative impact on youth participation in agribusiness in Vietnam, but not in Zambia. Barriers to effective youth engagement were; lack of start-up capital, low profitability of enterprises, and personal aspirations. Employing innovative value chain financing and market linkages can enhance enterprise profitability and youth participation in agribusiness.

1. Introduction

According to the UN’s World Population Prospects (2015), youth of working age (15–35) are expected to remain at close to 34% of the population for the next two decades. With an incredibly young and ever-increasing population, the population structure in most countries resembles that of an Egyptian pyramid with a narrow top and a wide base. This characteristic has been referred to as the youth bulge (Mueller et al. Citation2019; Hope Citation2012). This base even gets wider in rural than urban areas (Mueller et al. Citation2019). However, unlike in East Asia and the Pacific between 1965 and 1990 where, the rapidly growing youthful working-age population provided demographic dividends, in Africa this increase in numbers has created one of the biggest challenges of the twenty-first century – youth unemployment (Assaad and Levison Citation2013). Global youth unemployment rate of 13% is about three times higher than that among the adult population at 4.3% (ILO Citation2020). Taking all regions into consideration, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) had the highest youth unemployment rates (40%).

The causes of youth unemployment are believed to be multifaceted, ranging from an inadequate investment/supply side of jobs (Kabbani Citation2019), insufficient employable skills (Ayonmike and Okeke Citation2016), and high rates of labor force growth at 4.7% per annum (Brundage and Cunningham Citation2017). The World Economic Forum further accentuates the lack of quality education and relevance to the needs of the labour market as the key contributor to youth unemployment, in addition to other factors as; economic downturns and “Discouraged youth” where many young workers have given up hope of ever acquiring a meaningful job which provides a “living wage” (WEF Citation2014). Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) notes a mismatch between the current demand for labour, and the effective supply of young workers; i.e. many young workers are neither willing nor able to accept the kind of jobs that are available (OECD Citation2013). Addressing the scourge of youth unemployment is central to most countries and development partners because its escalation can result in increased rural-urban migration, increased income inequalities, increased crime and violence as most engage in risky behaviour, as well as brain drain through loss of trained and experienced young people to other economies.

Forbes (Citation2015) show that agriculture holds potential to provide employment opportunities for the youth if supported with increased investment and conducive institutional and policy environment. It is not surprising that agriculture is central in addressing the scourge of youth unemployment (Adesugba and Mavrotas Citation2016). It is the main source of livelihood for more than 600 million people in SSA, directly employing around 80% of the rural population and contributing an average of 25% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the region (Mukasa et al. Citation2017). In south and southeast Asian countries, agriculture’s share of GDP stood at 19% in 2016, and agricultural employment accounted for around 47.4% and 38.9% of total employment in south Asian and southeast Asian countries respectively, during the period 2003–2016 (Liu et al. Citation2020). Agribusiness, in particular, a term used to mean all activities and services along the agricultural value chain, can create job opportunities and generate incomes (Roepstorff, Wiggins, and Hawkins Citation2011). Other studies have also shown that stimulating entrepreneurship in the smallholder farming sector enables the attainment of economic goals at community and national levels (Magagula and Tsvakirai Citation2020; Sinyolo and Mudhara Citation2018).

These characteristics justify the centrality of the nexus between youth employment and agribusiness in formulating development policy. Youth participation in agriculture and related activities has been a key focus area of important global, regional and national policies. For example, African leaders, through the Malabo declaration (2014) committed to create job opportunities for at least 30% of the youth in agricultural value chains by 2025. A number of governments working with the ILO have developed policy frameworks and strategies as well as National Action Plans on Youth Employment (NAP) towards addressing this challenge (see https://www.youthpolicy.org/), with a key focus on youth engagement in agriculture and agribusiness.

Despite the potential of agriculture in providing youth employment opportunities and efforts in various contexts, there has been a slow response by the youth. Numerous sentiments regarding engagement of youth in this sector indicate a disinterest (Magagula and Tsvakirai Citation2020; Njeru Citation2017; Udemezue Citation2019). The studies indicate that most youth do not consider agriculture as a lifelong career that can sustain their lifestyle but view it as a poor man’s activity or one that is reserved for those who failed in school. Further evidence demonstrates that most youth view the sector from the farming perspective with backbreaking work (laborious) generating low productivity and offering less in return (Barratt, Mbonye, and Seeley Citation2012; Sumberg and Okali Citation2013; Afande, Maina, and Maina Citation2015; FSN Forum Citation2018; Daum and Birner Citation2017; Udemezue Citation2019; Yami et al. Citation2019). Although these are valid sentiments, they may not be homogenous across the youth demographic, taking cognizance of structural challenges that undermine their economic potential and ability to influence existing policy processes. Besides, the nexus between youth and agriculture has only partially been developed, limited by unavailability of evidence on opportunities and pathways for youth engagement in the sector.

This study therefore aimed to examine youth participation in agriculture and agribusiness, focusing in particular on what evidence is needed to inform responsive policies and interventions for youth engagement and employment in the sector. The specific research objectives were; (1) assess the nature of youth participation in agribusiness, and key indicators that inform their perceptions towards the agricultural sector, (2) investigate the effect of these perceptions and other factors impacting on youth participation in agribusiness; and (3) Assess opportunities for youth engagement along key agricultural value chains, including needed support networks, linkages and capacities. The study contributes to the emerging agricultural entrepreneurship literature, by emphasising the role of perceptions and other factors in determining youth decisions to participate in agribusiness, and engagement pathways for effective participation of the youth. The study is based on data collected in Zambia (Southern Africa) and Vietnam (Southeast Asia).

2. Context

The study was conducted in Zambia (Southern Africa) and Vietnam (Southeast Asia). These two countries present differing contexts in terms of youth unemployment, but their demographic population structures are representative of most of SSA and Asia, respectively.

Since 2000, Zambia has been registering economic growth averaging 6% per annum (World Bank Citation2016). This growth however has not been inclusive as the country’s headcount poverty stands at 60.5% (Mphuka, Kaonga, and Tembo Citation2017). Over the last decade, Zambia’s population has expanded at an annual average rate of almost 3%, exceeding the sub-Saharan African average (at 2.7%). The population is generally youthful with those aged less than 35 years estimated at 80% of the total population (Bhorat et al. Citation2015). The youth comprise 64% of the working-age population and 56% of the labour force (Bhorat et al. Citation2015), however, they are more likely to be unemployed than the non-youth. In 2019, unemployment rate in Zambia was at approximately 11%, while youth unemployment was at 21% (ILO, Citation2020). International Youth Foundation (IYF Citation2014) identifies agriculture as a key priority for government given the investments made in the sector, in form of seed, fertilizer and agribusiness. It further emphasizes the need to diversify young peoples’ skills beyond primary production in order to expand their economic opportunities. The Zambia national youth policy on the other hand points out the need for government to create a conducive environment for job creation and ensure alignment of skills with the requirements of the job market e.g. through work experience and apprenticeship programmes (Republic of Zambia Citation2015). This is in addition to making recommendations for the review of labour market policies and the legal regulatory framework, to make it more youth-responsive.

In Vietnam, youth comprise 25% of the country’s total population, and youth (15–24 years) unemployment stands at 7% (Plecher Citation2020). Young people are more likely than adults to be unemployed, as Vietnam is facing a challenge of equipping them with relevant skills for the growing service and manufacturing sectors, and creating jobs for them (OECD). Further, even for youth who are employed, the low wages and informal nature of their employment are matters of concern, with agriculture being the key sector for employment creation in Vietnam despite the ongoing industrialisation. In an effort to address these issues, the government of Vietnam has instituted various policies and come up with programmes to support youth in vocational training and promote entrepreneurship. The key policy is the Youth Law and The Vietnamese Youth Development Strategy 2011–2020.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

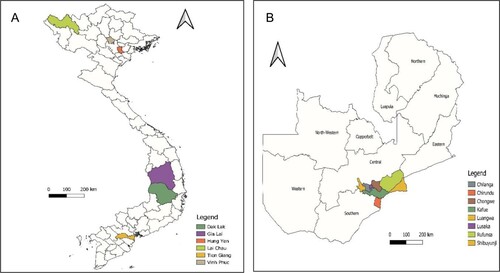

The study was conducted in Vietnam and Zambia. In Vietnam, the study was conducted in four of the 58 Provinces two in the north (Vinh Phuc and Hung Yen) and two in the south (Dak Lak and Tien Giang). In three of the four provinces, the study was conducted in only one district; Vinh Phuc (Tam Duong), Hung Yen (Phu Cu), Tien Giang (Cai Be) while in Dak Lak, the study was conducted in three districts (Cu Mgar, Cu Kuin and Krong Pac). In Zambia, the study was conducted in the Province of Lusaka (one of the 10 Provinces of Zambia) in four districts, Chilanga, Chongwe, Kafue and Lusaka. shows the study locations in Vietnam (A) and Zambia (B). The selection of study areas considered factors such as; diversity of agricultural activities, ease of reaching both rural and urban youth in a similar agro-ecological context, and locations where the research partners had physical presence for ease of coordination of the research activity.

3.2. Data collection

Data were gathered from youth and other stakeholders along selected value chains. Both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered through individual surveys, focus group discussions and key informant interviews.

Individual survey: Data were gathered through interviews with youth using structured questionnaires. Community leaders assisted in locating households with youth for interviews, with a target of reaching at least 100 households, the minimum sample required for a survey design. Face-to-face interviews with the youth were conducted by trained enumerators using a structured questionnaire that had been pretested for validity. The questionnaire was programmed on the Open Data Kit (ODK) platform and deployed on tablet computers which allowed the utilisation of in-built checks on data validity that restrict the entry and submission of data that does not meet the required criteria. At the end of the survey, a total of 113 youth (of whom 27% were female) were interviewed in Vietnam, of which 10% lived in urban and 90% in rural areas. In Zambia, 202 youth (of whom 38% were female) were interviewed of which, 46% lived in urban and 54% in rural areas. shows the distribution of respondents, by gender and location.

Table 1. Frequency of youth interviewed in Zambia and Vietnam.

Focus group discussions (FGDs): Within the enumeration areas, focus group discussions (FGDs) were held to enrich information from individual surveys. Separate group discussions for female or male youth were held to obtain perspective of male and female youth. At the end of the exercise, 16 FGDs were conducted in Vietnam and Zambia, eight per country. In total, focus group participants were 137; 59 females and 78 males (see ).

Interviews with value chain actors. Interviews with selected value chain actors were undertaken to understand youth engagement along the value chain. Information gathered included opportunities present, knowledge and capital requirements, eligibility criteria, technical support services provided, and required support to enhance youth participation. In Zambia, the analysis focused on dairy, poultry and horticulture, while in Vietnam, the review focused on marketing chains. The value chains were prioritised based on literature review, and recommendations by local partners of enterprises that hold potential to employ youth.

3.3. Empirical model

Youth participation in agribusiness was measured by using a binary variable that took up a value of 1 when an individual was engaged in any agricultural or agribusiness activity, and 0 otherwise. Given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable, its relationship with the various explanatory variables was estimated using a binary probit regression model. The general formula for binary probit model is given in Equation (1).

(1)

(1) where Yi is the dependent variable (participation in agribusiness), P is the main variable of interest and denotes perceptions of respondents with respect to agriculture. X is a vector of other explanatory variables, age, sex, education level, marital status, family size, access to extension, access to credit, membership in farmer/youth group, and perception of agriculture.

and

are the associated vector of parameters to be estimated, and

is the error term.

Perceptions of respondents with respect to the agriculture sector were obtained based on a set of 9 questions. A Likert-type scale was used where respondents indicated their level of agreement with the statements (see ). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to generate an index from the 9 questions which was then included as an explanatory variable in the probit model, to estimate the effect of perceptions on participation in agriculture. These variables have been theoretically and empirically linked with participation in agricultural activities for example (Magagula and Tsvakirai Citation2020).

3.4. Data analysis

Upon completion of the survey, data were downloaded from the aggregate server as comma separated value files and exported to STATA for analysis. Descriptive analysis was done and frequencies, means and proportions were generated, disaggregated by country and respondents’ gender in order to highlight any differences between male and female respondents. Probit regression model was used to model factors affecting youth participation in agribusiness.

3.5. Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents before interviews and discussions. Enumerators explained to participants first the purpose of the study, the data to be gathered and emphasized that participation was voluntary and there were no financial benefits or otherwise to their participation. Enumerators also explained that the data collected would be handled in a way that would not affect the anonymity of the participant, though personal data was gathered to aid follow up where necessary. Verbal consent was obtained based on its practicality, and not to raise unnecessarily anxiety associated with persons appending their signatures on documents.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent characteristics

shows a summary of respondents’ characteristics for both countries. At the time of the interview, only 9% of the respondents in Zambia were still in school; 95% in secondary school and 5% in college. Those who were not currently in school had attained at least secondary education (58%), or primary education (33%). About 3% indicated that they did not complete any education level. At least 59% of the respondents were married. The average household size was five, with a minimum of one and a maximum of six members. Over 80% of the respondents owned mobile phones and 46% and 35% belonged to social media groups and community groups respectively. At least 44% of respondents indicated that they had received extension services at least once in the previous 12 months, with the extension offices located within 5 km distance from the respondents’ homes, on average. Input and output markets were located far off, 22 and 17 km respectively.

Table 2. Respondent characteristics.

In Vietnam, 14% of the respondents were in school at the time of the interview, 19% of whom were in technical and vocational training while 81% were in college. All the respondents who were not in school as at the time of the interview had attained secondary or tertiary level education. At least 52% of the respondents were married, and the average household size was four persons. All respondents owned a mobile phone, and 88% belonged to social media groups. About 30% belonged to community groups, while 42% indicated that they had received extension advice during the 12 months prior to the study. The average distance to the input and output markets was 2 and 4 km respectively.

4.2. Youth engagement in agribusiness

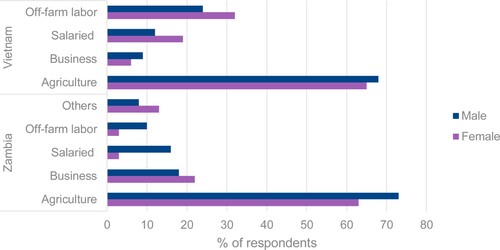

The majority of youth, 67% in Vietnam and 69% in Zambia were engaged in the agribusiness as their primary source of livelihood. Off-farm labour was the second most important livelihood activity by the youth in both countries, with more female than male youth engaging in this activity, in Vietnam. More female youth in Vietnam were in salaried employment, compared to their male counterparts ().

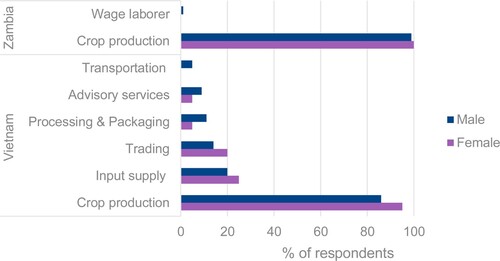

Agricultural production, particularly crop production was the most dominant agribusiness activity, engaging 99% and 88% of respondents in Zambia and Vietnam respectively. In Vietnam, the youth also engaged in other activities such as input supply, sale of agricultural produce, processing and packaging, advisory services, and transportation (). Under input supply, the youth engaged in sale of fertilizers, pesticides, seed, manure, and cattle feed/fodder. Those providing advisory services were either community facilitators or lead farmers.

In Vietnam, the most commonly grown crops were rice, coffee, durian, longan tree, black pepper and avocado (). Apart from the key staples; rice and maize, that were grown mainly for home consumption, the other crops were largely grown for income/sale. The different climatic condition between northern and southern of Vietnam influenced the type of crops grown in these regions. Fruit crops farming plays an important role in income generation, and therefore more youths in Southern Vietnam were involved in this enterprise. In Zambia, maize, groundnuts, and sweet potatoes were mainly grown for home consumption while rape, tomato, cabbage and soybean were grown primarily for cash. Besides the enterprise specific reasons, such as suitability of the crop to agroecological zone, respondents mentioned preference for short maturing crops such as vegetables and those that don’t require a lot of labour input.

Table 3. Crops and livestock enterprises by respondents (%).

The youth also engaged in animal production albeit by a small proportion of respondents. The youth mainly produced small ruminants, swine and poultry, owing to their high returns on investment, ease of feeding, market availability, minimal labour, and high productivity. Poultry was the most popular animal enterprise in Zambia, with 54% of the respondents engaging in this enterprise. Goats and sheep (shoats) were kept by 25% of youth in Zambia, but none in Vietnam. Proportionately more youth in Vietnam engaged in pig production, which was their number one animal enterprise compared to Zambia. Generally, livestock production was more pronounced in Zambia than in Vietnam.

4.3. Perceptions of the youth regarding the agricultural sector

presents a summary of the statistics on the perceptions of the youth regarding the agricultural sector. The interviewed youths had mixed perceptions regarding the agricultural sector, which ranged from positive (Zambia) to negative (Vietnam). The average mean score of the perception indicators for Zambia was 1.95 (1.87 for female and 2.00 for male). This implies that the respondents were inclined to perceive positively the agricultural sector’s ability to provide opportunities for them, and is not for old people per se. Female youth were more positive than male youth about the potential of agriculture in providing income. In particular, the scores challenged the general perceptions that agriculture is for old people (mean score 1.29), educated youth don’t want to engage in agriculture (mean score 1.60), and youth don’t want to be engaged in agriculture (mean score 2.5). In Vietnam on the other hand, the average mean score was 2.86 (2.84 for female and 2.87 for male). The higher score indicates that the respondents were more indecisive or held more negative perceptions about the potential of agriculture in providing opportunities for them, compared to those in Zambia. For example, a score of 3.7 and 3.35 on the indicator “Youth do not want to be involved in agriculture” and “People engage in agriculture due to lack other income options” respectively, implies that they generally agreed with these assertions. Magagula and Tsvakirai (Citation2020) study in South Africa show that the youth held positive economic perceptions of the agricultural sector, yet were unconvinced of the alignment between the agricultural sector’s activities and the values held in their social circles. Similarly, Metelerkamp, Drimie, and Biggs (Citation2019) show that attitudes towards careers in agriculture vary greatly, with a set of negative perceptions as well as clear interest in and passion for agriculture by the youth.

Table 4. Perception of youth regarding the agricultural sector and participation in agriculture.

4.4. Pull and push factors for youth engagement in agribusiness

Respondents were asked about the pull (motivating) and push (demotivating) factors for engagement in agribusiness (). In Vietnam, the most commonly mentioned pull factors were land availability (83%), possession of agriculture related knowledge and skills (57%), and contribution of agriculture to household livelihood improvement (48%). Community support and job opportunities were other responses given by respondents in Vietnam. In Zambia on the other hand, respondents mentioned agricultural skills (51%), and access to credit (50%) as the major pull factors. Perception of agriculture contribution to livelihoods as a pull factor was significantly different between male and female youth, where the latter put more weight to it.

Table 5. Push and pull factors for youth engagement in agriculture (%), following surveys in Zambia and Vietnam.

The push factors were similar to a large extent as the mentioned pull factors, e.g. access to land, access to finance, and possession of agriculture-related skills. This implies that while these factors would help the youth to participate in agriculture, the continued limited access to these factors by the youth ultimately affects their effective participation in agribusiness. Besides, the low profitability of agriculture, lack of market access and lack of functioning infrastructure were mentioned as the key market factors pushing the youth away from participation in agribusiness. Low profitability was more pronounced in Vietnam compared to Zambia.

Personal attributes such as perceptions, aspirations, and education level were considered push factors for engagement in agriculture. Considering that a majority of interviewed youth had attained some educational qualifications, the aspiration of most of them was to be engaged in a sector where they could use their acquired knowledge. Finally, uncertainty of agriculture and production risks associated with the sector was considered a push factor, although only mentioned by respondents in Zambia.

4.5. Effects of perception and socio-economic factors on youth participation in agribusiness

shows the results of the probit model of factors affecting youth participation in agriculture. In both Zambia and Vietnam, age of respondent and access to extension advice were significantly and positively correlated with participation in agribusiness. This implies that as persons grow older, they are more likely to engage in agriculture than younger ones, while access to agricultural advice is more likely to motivate participation in agriculture. Less participation by younger people may be expected considering that they may be in school or have relatively less capital to initiate own agricultural activities. Location of the respondent, urban vs rural influenced their participation in agriculture, although it was different for Vietnam and Zambia. In Zambia, location in urban areas was likely to negatively influence youth participation in agriculture, while the reverse was true in Vietnam. This could be because the respondents in Vietnam also engaged in non-farm agricultural activities such as input supply, trading, processing and packaging, provision of advisory services and transportation, compared to Zambia where almost all respondents were engaged in farm production.

Table 6. Probit model results of factors affecting youth participation in agriculture.

The data further shows that the perceptions of youth had statistically significant (P < 0.01) negative impact on participation in agriculture in Vietnam, but not Zambia. This is not surprising considering that a majority of youth in Vietnam showed indecisive or negative perceptions towards agriculture. Membership to farmer or youth groups showed positive effect on youth participation in agriculture in Vietnam and not in Zambia.

4.6. Youth participation and opportunities in value chains

4.6.1. Dairy value chain in Zambia

Interviews were held with officials at the Dairy Association of Zambia (DAZ), which is a national membership-based organisation, representing the dairy sub-sector country-wide. Membership includes all categories of dairy producers, processors and dairy related agribusiness and is open to individuals, associations, partnerships, companies, corporations, cooperative societies and others. With support from development partners, DAZ took deliberate steps to fund business proposals from youth and women, in line of production of feed, baling and selling of fodder/pasture, provision of milking services, and milk transportation. There are also opportunities for small scale value addition e.g. making yoghurt, cheese, ice cream etc. There were still very few players in value addition, yet it is considered feasible for youth given th, where the youth can participate, though they were not yet engaged. Knowledge in animal nutrition, milking and milk handling, disease control, and reproduction were considered key for effective participation in the dairy value chain. The recently developed Digital Information Management System (funded by the Swedish Embassy), is anticipated to improve access to information, inputs and equipment for small scale dairy farmers as well as improve financial inclusion for targeted small-scale dairy farmers. DAZ anticipates to create 200 milk collection centres on top of the already existing 74 centres. The youth can optimise benefits provided by the system to link with farmers, markets and input providers and various centres.

4.6.2. Horticulture (fruits and vegetables) value chain in Zambia

Interviews were held with officials at the Zambia Export Growers Association (ZEGA). This is an association of exporters of fruits, vegetables and cut flowers. Main products exported were; asparagus, runner beans, sugar snap, fine beans, red chilies, cut flowers, passion fruits, baby corn, and mange tout. Tight controls existed in this value chain and entry or participation by the youth was not obvious. There was an observed opportunity for youth however, to engage in organised production (contract farming or registered businesses) and aggregation of preferred varieties supplying export firms. On the other hand, statistics indicate that Zambia is a net importer of fruits and vegetables. In the year 2014 alone, Zambia imported vegetables worth US$412.6million (APF Citation2015). This shows the potential for local production in contributing to wealth and income of smallholder famers. Local production of vegetables can open opportunities for participation of youth who may not have the networks and capital required by export markets. The youth can be involved as producers, transporters, aggregators, traders or processors in horticulture value chains.

4.6.3. Poultry value chain in Zambia

Interviews were held with Poultry Association of Zambia (PAZ). The PAZ is an affiliate of the Zambia National Farmers’ Union under the specialised/commodity Association category of membership. Membership of the Association is available to individuals, associations, partnerships, companies and others, engaged in the business of poultry farming. There was a high engagement of youth in this value chain compared to those assessed earlier, owing to low investment capital required. The poultry value chain is also less structured enabling entry by various players. The youth were engaged in distribution of feed, production of broiler chicken, transport of birds to the market, and value addition (smoking chicken for preservation). Other identified opportunities for youth were; production of feed and vaccinations, and offering vaccination services. Technical knowledge at least to degree level was a necessity for these specialised services. For vaccination services, service providers undergo short trainings and act as brokers obtaining commission on each bird vaccinated. Innovations along the value chain that could enhance participation of youth include; an online platform linking producers to the market; better, and more cost-effective feed formulation technologies.

4.6.4. Market linkages Vietnam

Interviews were done with BAYER and OLAM. Both are multinational companies engaged in research and development of various agricultural value chains. The main products being considered were pepper, coffee, pomelo, dragon fruit, tomatoes, cabbages and rice. Youth were mainly involved in plantation management; grading activities and quality control; packing into market-based products; and promotional activities. However, these were youth who were formally hired by the companies to provide such services. Interviews with the company showed that youth could participate in production of demanded crops and input service provision. Service provision would take the form of procurement and marketing of produce; provision of advisory services either call advisory or farmer field school (FFS) facilitation; and provision of technology e.g. precision or smart agriculture for input management. However, it was noted that formal education and specialised training in specific aspects of the value chains was key for youth participation in the identified opportunities.

Based on the value chain analysis and focus group discussions, various opportunities for youth engagement in agriculture were identified, which include; (a) Own production and supply of produce I particular high value crops either through contract farming, out grower schemes or organised production under youth groups/cooperatives; (b) Service provision along the value and in so doing earn a commission. Linkages to farmers and markets are key and it ensures that farmers get access to inputs (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides), post-harvest handling technologies (threshing, shelling, bagging) and training, transportation, extension services, good agronomic practices (pruning, spraying, irrigation etc.); (c) Value addition e.g. first-stage food processing like flour milling, milk products (butter, yoghurt), beer or processed meat. Although rural areas are limited in terms of access to market and infrastructure, opportunities exist in early value addition; (d) Youth in agriculture and enterprise, where young people can initiate agricultural enterprises at different nodes along the value chain as a worthwhile alternative source of employment and income generation; (e) Use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) – besides the traditional value chain activities, youth could harness the benefits of ICTs to provide services along the value chain. For example, market information services, e-advisory services, smart control system for pests and disease management, product tracking, quality control etc.

The governance of the assessed value chains can be grouped as; company-led; farmer association managed; and open value chains. The organisation presents the level of complexity and specialisation (informal vs. formal), which dictate conditions of entry and participation, especially by the youth. For example, dairy value chains are generally formal and more controls exist thus participants require some form of licensing to be able to participate. The analysis further reveals the need for appropriate skills, organisation, business plans for the youth to effectively participate and benefit from lucrative value chains. In the current analysis, youth participation is not obvious for more formal and controlled value chains as firms involved will hire for the skills they require or youth require specialised knowledge. Less formal value chains (e.g. poultry in Zambia) are open for new entrants, controls are few, and specialised knowledge is not a key requirement, although benefits are low and opportunities for exploitation may arise. Organisation of youth into business entities, coupled with skills in enterprise selection, planning and management can open chances for participation in organised production, aggregation and value addition of high value products.

5. Discussion

This study assessed the extent of youth participation in agri-enterprises, and barriers and opportunities for enhanced engagement and benefit. Results are based on survey of youth in rural and urban settings in Vietnam (SE Asia) and Zambia (Southern Africa), and interviews with value chain actors. The majority of youth were engaged in agricultural activities, mostly farm production, and provision of services. The youth mainly engaged in crop production, particularly high value and early maturing crops, citing better returns. The selection of crop enterprises by the youth is in agreement with other studies (Trevor and Kwenye Citation2018), which show that the youth target niche markets to start ventures whose produce moves quickly. Similarly, in the animal enterprises, the youth were engaged in poultry, given its quick turnaround period. This, coupled with the high demand particularly for indigenous chicken, provided opportunities for increased engagement in poultry value chains (Bwalya Citation2014).

Youth reported various factors that motivate or hinder them to participate in agriculture – push and pull factors. Key factors identified in this study were grouped into three categories; production resources, market and marketing factors, and personal aspirations and perceptions. Production resources included; land, capital, labour and knowledge/skills, yet the majority of youth did not have access to them. As noted earlier, establishment of agriculture-based enterprises requires capital input to buy stock and equipment which in most cases are not affordable by the youth. Some of these factors have been reported by other scholars as important push factors to youth engagement in agriculture (Udemezue Citation2019) . Availability of finance (capital) can enable youth to access assets and essential inputs for production, processing and transport (Akpan Citation2010). Possession of specialised knowledge and skills, such as processing, feed making, advisory services etc is important for management of agricultural enterprises (Robinson-Pant Citation2016). Lack of land and other assets also makes it incredibly difficult for the youth to access finances because they have nothing to use as collateral in financial institutions. Therefore, enabling access to land and other capital can go a long way in facilitating increased production capacity to meet market demand especially if empowered in key skills.

Market and marketing factors included; low profitability of agricultural produce, poor market accessibility, and poor infrastructure. These factors are compounded by weak relations with market agents, limited basic knowledge of the market system, limited information on market conditions and prices, and consumer preferences, which are characteristic of smallholder agricultural activities. Most smallholder farmers sell a small amount of produce and due to the absence of economies of scale, the cost of handling, assembling and transporting their produce is high relative to that of larger scale farmers. Providing smallholders with market intelligence and entrepreneurial skills training can therefore improve their understanding of market opportunities and enable them to better manage their farms as businesses (Robinson-Pant Citation2016). Considering that the majority of youth owned mobile phones, opportunities in the utilisation of Information Communication and Technology (ICT)-based approaches could be optimised to help address the marketing challenges, while at the same time providing opportunities for youth to engage in agribusiness. Successes in the use of ICTs in the provision of market information, e-advisory services, smart control system for pests and disease management, product tracking, online marketing, quality control etc., have been documented (Irungu, Mbugua, and Muia Citation2015).

The youth held various perceptions about agriculture, ranging from positive in Zambia to negative in Vietnam. Probit model results also showed a significant negative relationship between perceptions and participation in agriculture for respondents in Vietnam. This implies that the youth in Vietnam would prefer to pursue alternative livelihood strategies, especially those youth that had attained some qualifications. This can also be observed from the fact that youth in Vietnam tried diversified agricultural activities along the value chain as opposed to those in Zambia who were mainly engaged in farm production. The lack of resources to operate at other levels of the value chain, force a majority of youth to engage in production activities which are considered manual and less profitable. Some studies have also shown similar perceptions that agriculture is laborious yet it offers less in return (Yami et al. Citation2019).

Market and value chain analyses showed various opportunities for engagement by the youth. However, the noted levels of specialisation in the various value chains with associated requirements in terms of technical knowledge, capital, organisation, and business skills to effectively participate and benefit from them. The value chains ranged from less formal e.g. poultry farming with relative ease of entry, to more formal and controlled value chains e.g. export horticulture, where youth participation was not obvious due to controls. However, the more informal the value chain is, the less the benefits to participants and opportunities for exploitation may arise. Therefore, youth need to be facilitated to operate in more formal value chains where benefits and returns are commensurate with their investments.

Based on results of the analysis, this study has identified three key areas for action to enhance youth participation and benefit from agribusiness. Government agencies and development organisations supporting youth need to design and implement interventions based on an integrated approach that considers diversity of youths’ aspirations, interests, expectations, and challenges related to access to resources, as reported elsewhere (Yami et al. Citation2019).

Organisation of youth and market linkages: Organisation of youth into business entities can open chances for them to participate in organised production, aggregation, market linkages, and value addition of high value products. Farmer organisation further ensures that participants benefit from economies of scale.

Employing innovative value chain financing approaches: The production and supply of high-quality products requires financial investments which most youth farmers cannot afford. Innovative value chain financing can play a role in addressing capital requirements, at the same time achieving markets for products. Value chain financing (VCF) models have been used in various initiatives to address the challenge of financing for actors. Some are based on harnessing social capital for the participants, while others are buyer-driven (e.g. contract farming and production agreements). Contract farming is seen as tool for creating new market opportunities and leading to positive outcomes for producers and buyers (Wainaina, Okello, and Nzuma Citation2012). Social-capital based models include brokerage, production credit, or guarantee schemes where a person accesses inputs or services using social capital as collateral.

Business capacity enhancement: Existing private and government efforts to support businesses development for youth and women, have been constrained in part due to lack of skills in business management. Therefore, capacity building and continuous mentorship on enterprise selection, planning and management are important for youth to start and sustain agribusinesses. Interventions that integrate modern technology and ICTs are helpful in helping start-ups to navigate market challenges.

6. Conclusion

Although several studies have indicated disinterest of youth in agribusiness, this study showed that a majority of youth interviewed were engaged in agricultural activities at various levels, and perceptions were mixed based on context. Farm production was the most dominant agribusiness activity, particularly in Zambia, and youth grew both food and cash crops. In Vietnam, the youth were engaged in other value chain activities, besides production, providing more diversified engagement compared to those in Zambia. This echoes the observed differences in knowledge levels, perceptions, and context of youth in Vietnam and Zambia, which were also important factors affecting youth participation in agriculture generally. Similarly, there were observed differences in levels of participation between male and female youth in agribusiness linked to inherent differences in resource capacity and aspirations. Market and marketing challenges associated with agricultural enterprises were mentioned, though these are not necessarily unique to youth but smallholder agricultural production.

In view of this, we make context-based and general recommendations for enhancing youth engagement in agribusiness. In Zambia, and similar contexts where the youth are more engaged in agricultural production, there is need to build their organisational capacity to benefit from organised production, access to land (e.g. through loans to acquire land or leasing) and labour-saving production equipment, linkages to lucrative and niche markets, and processing/value addition. In Vietnam, and similar contexts where the youth are engaged in diversified activities along the value chain, with low perception of agricultural production, support should be provided for business development, and knowledge enhancement to provide services along the value chain. Overall, an integrated approach that enhances access to finance through promoting financial products catered for the youth, mentoring and business skills development programs, organisational capacity of the youth, and start-up funding opportunities to help remedy the challenges faced by the youth are recommended. Interventions that integrate modern technology and ICTs will also be helpful in helping youth start-ups to navigate market challenges.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the CABI Development Fund (CDF). CABI is an international intergovernmental organisation and we gratefully acknowledge the core financial support from our member countries (and lead agencies) including the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), China (Chinese Ministry of Agriculture), Australia (Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research), Canada (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Netherlands (Directorate-General for International Cooperation-DGIS), Switzerland (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation) and Ireland (Irish Aid, International Fund for Agricultural Development-IFAD). See https://www.cabi.org/aboutcabi/who-we-work-with/key-donors/for details’. We are grateful for the support and technical input provided by Dr. Dennis Rangi, Dr. Ulrich Kuhlmann, Dr. Morris Akiri, Dr Sivapragasam Annamalai, and Dr Tran Danh Suu (VAAS). We also extend our gratitude to the team that gathered this information from field; Nguyen Ngoc Khanh, Tran Duy Lieh, Nguyen Thi, Cam Giang, Hoang Trong Hung and Tran Duy Lich from Vietnam and from Zambia; Demein Ndalameni, Hazel Phiri, Tibonge Lifune and Danwell Siabusu. We appreciate the respondents who provided data for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joseph Mulema

Joseph Mulema (PhD) is Senior Scientist (Research) at CABI (Nairobi). He has worked extensively on various subjects in International development that address improving livelihood of smallholder farmers covering all various social categories.

Idah Mugambi

Idah Mugambi (Msc) is a Data and Knowledge Management specialist at CABI, with over five years' experience in research and development work. She is particularly keen on the use of digital tools to deliver practical extension advisory services to small scale farmers, and the use of agricultural data in decision making.

Monica Kansiime

Monica Kansiime (PhD) is Senior Scientist- Agricultural Economist at CABI. She has 14 years field experience working in research and development. She has published research in social sciences, market studies, climate change adaptation, agricultural extension, and seed systems. She is a seasoned process facilitator, including farmer participatory approaches, multi-stakeholder innovation platforms, beneficiary assessment and participatory impact evaluation.

Hong Twu Chan

Hong Twu Chan (MSc) was a scientist at CABI South East Asia, where she conducted multiple scientific research and development projects, including implementing and managing a GEF-funded project on Invasive Alien Species.

Michael Chimalizeni

Michael Chimalizeni has over 10 years' experience in development work focusing on a variety of information types and platforms. He has worked for various local and international NGOs. He now contributes to ICT/ICM capacity building projects for librarians, researchers and academics in Sub-Saharan Africa through his training work with ITOCA. Michael is also a Carnegie Fellow and Commonwealth Scholar. He previously worked with CABI as Regional Sales Manager for CABI books and publications, and is currently serving as Advisory Board Member for ZimLibrary.

Thi Xuan Pham

Thi Xuan is a Researcher at the Vietnam Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VAAS). She led data collection, analysis in Vietnam and translation of responses to English.

George Oduor

George Oduor (PhD) is a Senior Research Scientists at CAB International. He is an International development (Integrated Crop & Pest Management) expert in the areas of agriculture and the environment, with 35 years experience working in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe. He has a track record on projects, programmes and partnerships management involving multi-cultural and multi-institutional stakeholders, which mainly aim at improving livelihoods of smallholder farmers. He holds a PhD in Crop Protection from the University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

References

- Adesugba, Margaret, and George Mavrotas. 2016. Delving Deeper into the Agricultural Transformation and Youth Employment Nexus: The Nigerian Case. Working Paper 31. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Afande, Francis Ofunya, William Nderitu Maina, and Mathenge Paul Maina. 2015. “Youth Engagement in Agriculture in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects.” Journal of Culture, Society and Development 7: 4–19.

- Akpan, Sunday Brownson. 2010. Encouraging Youth’s Involvement in Agricultural Production and Processing. Abuja: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- APF. 2015. “Mapping of Investment Opportunities in the Horticulture Sub-Sector: The Case of Vegetable Value Chains in Zambia.” In Horticulture Subsector Study Report. Agri Profocus, Agribusiness Incubation Trust and SNV.

- Assaad, Ragui, and Deborah Levison. 2013. Employment for Youth: A Growing Challenge for the Global Community. Working Paper. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Ayonmike, Chinyere Shirley, and Benjamin Chukwumaijem Okeke. 2016. “Bridging the Skills Gap and Tackling Unemployment of Vocational Graduates Through Partnerships in Nigeria.” Journal of Technical Education and Training 8: 2.

- Barratt, Caroline, Martin Mbonye, and Janet Seeley. 2012. “Between Town and Country: Shifting Identity and Migrant Youth in Uganda.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 50 (2): 201–223. doi:10.1017/S0022278X1200002X.

- Bhorat, Haroon, Aalia Cassim, Gibson Masumbu, Karmen Naidoo, and Francois Steenkamp. 2015. Youth Employment Challenges in Zambia: A Statistical Profile, Current Policy Frameworks and Existing Interventions. Ottawa, Canada: International Development Research Centre and the MasterCard Foundation.

- Brundage, Vernon, and Evan Cunningham. 2017. Unemployment Holds Steady for Much of 2016 But Edges Down in the Fourth Quarter. Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Bwalya, Richard. 2014. “An Analysis of the Value Chain for Indigenous Chickens in Zambia’s Lusaka and Central Provinces.” Journal of Agricultural Studies 2 (2): 32–51.

- Daum, Thomas, and Regina Birner. 2017. “The Neglected Governance Challenges of Agricultural Mechanisation in Africa – Insights from Ghana.” Food Security 9 (5): 959–979. doi:10.1007/s12571-017-0716-9.

- Forbes. 2015. “Job Creation in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Forbes Insights and Djembe Communications.

- FSN Forum. 2018. Youth Employment in Agriculture as a Solid Solution to Ending Hunger and Poverty in Africa. Report of Activity. Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition.

- Hope, Kempe Ronald. 2012. “Engaging the Youth in Kenya: Empowerment, Education, and Employment.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 17 (4): 221–236. doi:10.1080/02673843.2012.657657.

- ILO. (2020). Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the future of jobs. International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_737648.pdf.

- Irungu, K. R. G., D. Mbugua, and J. Muia. 2015. “Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) Attract Youth into Profitable Agriculture in Kenya.” East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal 81 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1080/00128325.2015.1040645.

- IYF. 2014. A Cross-Sector Analysis of Youth in Zambia. Baltimore: YouthMap Zambia. International Youth Foundation.

- Kabbani, Nader. 2019. Youth Employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Revisiting and Reframing the Challenge. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

- Liu, Jianxu, Mengjiao Wang, Li Yang, Sanzidur Rahman, and Songsak Sriboonchitta. 2020. “Agricultural Productivity Growth and its Determinants in South and Southeast Asian Countries.” Sustainability 12: 4981. doi:10.3390/su12124981.

- Magagula, Buyisile, and Chiedza Z. Tsvakirai. 2020. “Youth Perceptions of Agriculture: Influence of Cognitive Processes on Participation in Agripreneurship.” Development in Practice 30 (2): 234–243. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1670138.

- Metelerkamp, Luke, Scott Drimie, and Reinette Biggs. 2019. “We’re Ready, the System’s Not – Youth Perspectives on Agricultural Careers in South Africa.” Agrekon 58 (2): 154–179. doi:10.1080/03031853.2018.1564680.

- Mueller, Valerie, James Thurlow, Rosenbach Gracie, and Ian Masia. 2019. “Africa’s Rural Youth in the Global Context.” In Youth and Jobs in Rural Africa: Beyond Stylized Facts, edited by Valerie Mueller, and James Thurlow, 1–21. New York: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Mphuka, C., O. Kaonga, and M. Tembo. 2017. Economic Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Estimating the Growth Elasticity of Poverty in Zambia, 2006-2015. Department of Economics, University of Zambia. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Mphuka-et-al_Final-report_cover.pdf.

- Mukasa, Adamon N., Andinet D Woldemichael, Adeleke O. Salami, and Anthony M Simpasa. 2017. “Africa’s Agricultural Transformation: Identifying Priority Areas and Overcoming Challenges.” Africa Economic Brief 8 (3): 1–16.

- Njeru, Lucy Karega. 2017. “Youth in Agriculture; Perceptions and Challenges for Enhanced Participation in Kajiado North Sub-County, Kenya.” Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences 7 (8): 203–209.

- OECD. 2013. “The OECD Action Plan for Youth: Giving Youth a Better Start in the Labour Market.” Paper Presented at the Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level Paris, 29–30 May 2013.

- Plecher, H. 2020. Youth Unemployment Rate in Vietnam in 2019.

- Republic of Zambia. 2015. 2015 National Youth Policy Republic of Zambia, Ministry of Youth and Sport, Lusaka. https://www.myscd.gov.zm/?wpfb_dl=46.

- Robinson-Pant, Anna. 2016. Learning Knowledge and Skills for Agriculture to Improve Rural Livelihoods. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- Roepstorff, T., S. Wiggins, and A. T. Hawkins. 2011. “The Profile of Agribusiness in Africa.” In Agribusiness for Africa’s Prosperity, edited by K. K. Yumkella, P. M. Kormawa, T. M. Roepstorff, and A. M. Hawkins, 38–56. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

- Sinyolo, Sikhulumile, and Maxwell Mudhara. 2018. “The Impact of Entrepreneurial Competencies on Household Food Security Among Smallholder Farmers in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa.” Ecology of Food and Nutrition 57 (2): 71–93. doi:10.1080/03670244.2017.1416361.

- Sumberg, James, and Christine Okali. 2013. “Young People, Agriculture, and Transformation in Rural Africa: An “Opportunity Space” Approach.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 8 (1–2): 259–269. doi:10.1162/INOV_a_00178.

- Trevor, Sichone, and Jane Musole Kwenye. 2018. “Rural Youth Participation in Agriculture in Zambia.” Journal of Agricultural Extension 22 (2): 51–61.

- Udemezue, J. C. 2019. “Agriculture for All; Constraints to Youth Participation in Africa.” Current Investigations in Agriculture and Current Research 7 (2): 904–908. doi:10.32474/CIACR.2019.07.000256.

- Wainaina, W., J. Okello, and J. Nzuma. 2012. Impact of Contract Farming on Smallholder Poultry Farmers’ Income in Kenya. The International Association of Agricultural Economists Foz do Iguacu.

- WEF. 2014. Global Risks. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- World Bank. 2016. World Development Indicators. Technical report, Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Yami, M., S. Feleke, T. Abdoulaye, A. D. Alene, Z. Bamba, and V. Manyong. 2019. “African Rural Youth Engagement in Agribusiness: Achievements, Limitations, and Lessons.” Sustainability 11: 185. doi:10.3390/su11010185.