?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Women’s empowerment is recognised as an important strategy to foster gender equality. Its achievement requires an approach that targets normative and structural drivers of gender inequality. Nigerian women continue to face socio-economic challenges and are unable to exercise their agency within their homes. We evaluated a cluster-randomised control trial that aimed to increase women’s household decision-making by working with couples in three critical areas: spousal relations, and financial and reproductive decision-making. The trend overall suggested gains in some domains of decision-making but the results were mixed. More research is needed for improved context-specific measurement of decision-making as well as programme adaptation.

Background

Overview

Sub-Saharan African women continue to face socio-economic challenges and limited reproductive freedoms, which diminishes their ability to fully participate in decisions critical to themselves, their households, and the broader community. Women’s empowerment is recognised as an important strategy, embedded in international development discourse including the Sustainable Development Goals, to foster gender equity and create conditions for women to have voice and agency in the things that matter to them (United Nations Citation2015). However, while there is growing interest in the concept, operationalising the concept, and creating conditions that can accelerate progress towards it, remain a challenge, and numerous debates abound on its conceptualisation and measurement.

While cross-disciplinary discussions and debates on what constitutes “empowerment” continue, there is general agreement among scholars on some of its core components (Kabeer Citation1999; Malhotra and Schuler Citation2005; Richardson Citation2018). Firstly, empowerment is viewed to be a multi-dimensional process (e.g. economic, reproductive, familial) that occurs over time and varies by context and can be operationalised across households, communities, and larger groupings (Malhotra and Schuler, Citation2005). Secondly, as opposed to other disadvantaged groups, household and familial relationships are recognised as key sites of women’s disempowerment. Hence, systemic transformations at the household level are seen as necessary for paving the way for empowerment. Thirdly, agency or the ability to make choices and act upon them lie at the heart of empowerment. The notion of agency, drawing on feminist and human rights literature, places importance on women themselves having to undergo some degree of inner transformation or awareness that facilitates their ability to challenge discriminatory gender/social norms and exercise choice in their lives (Malhotra and Schuler Citation2005). This emphasis on agency came out of increasing realisation among practitioners and researchers that while resources are necessary to remove structural barriers and create enabling conditions for empowerment to occur, their presence alone does not guarantee it. It became increasingly clear that without women’s ability to recognise and use resources in their own interest, particularly by challenging discriminatory gender and social norms, resources alone may not bring about empowerment (Malhotra and Schuler, Citation2005). However, recent scholars have cautioned against conducting research with preconceived notions about how agency should be exercised as women may face multitudes of constraints within their context. They advocate for the need for more nuanced measures that capture the meanings women themselves attach to their actions, given their unique barriers (Mannell, Jackson, and Umutoni Citation2016).

Nalia Kabeer's (Citation1999) definition of empowerment continues to be one of the most influential definitions of empowerment because it captures many of the elements discussed above. She defines empowerment as a process of change by which those who were previously denied the ability to make strategic life decisions acquire such an ability. For empowerment to materialise, she emphasises the presence of three inter-related dimensions – resources, agency, and achievements. While agency is the ability to define one’s goal and act on them; resources, which include material, human, and social resources, including social relationships, enhance or create conditions that allow the exercise of agency. Achievements are the outcomes of empowerment. A more recent definition, drawing on Kabeer, views empowerment as both a process and an outcome, and defines it as the expansion of choice and strengthening of voice by transforming power relations (Eerdewijk et al. Citation2017). The authors describe the interaction between three elements – agency, institutional structure, and resources – as important to pave the way for empowerment. Agency refers to the capacity for purposive action, while resources are tangible and intangible capital and sources of power such as knowledge, skills, assets, social capital, and critical consciousness. Institutional structures are the social arrangements of rules and practices that govern family, community, and market relations. They comprise formal laws and policies as well as norms that shape human relations. They shape the expression of agency as well as control over resources.

Drawing on these definitions of empowerment, we conceptualised and tested the efficacy of a multi-pronged programme that aimed to increase female participation in household decision-making by simultaneously targeting the structural and normative barriers that impede the exercise of female agency at the household level. The intervention targeted three important domains of women’s disempowerment within their homes: gendered power relationships between spouses, and participation in reproductive and financial decision-making. We theorised that by targeting these areas, the programme will create a solid platform for empowerment because of their cross-cutting benefits. For example, most critically, gender norms can intervene in the ability of women to transform resources into actual outcomes that change or challenge intra-household gender inequities, and hence need to be addressed for any transformation to take place at the household level (Kabeer Citation1999). Here it is also clear that male partners need to be involved to successfully shift power imbalances within homes rather than placing the burden on women alone, as well as to avoid any unintended consequences and creating an enabling environment. Similarly, women’s economic empowerment can improve their status and bargaining power within the household, as well as facilitate the exercise of reproductive freedoms (Schuler, Hashemi, and Riley Citation1997; Schuler and Hashemi Citation1994). Also, understanding modern contraceptive methods and how to access them not only broadens reproductive choice but also provides women with the time and opportunity to invest in themselves and their relationships (Sonfield et al. Citation2013; Canning and Schultz Citation2012). Here again, male support and participation is seen as critical for reducing reproductive coercion and avoiding the negative risks and other costs associated with covert contraceptive use.

Currently, there are limited rigorously evaluated multi-sectoral interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly interventions that work at the household level with both partners, and attempt to shift the normative as well as structural drivers of gender inequality between spouses. Nonetheless, there is increasing recognition that stand-alone economic empowerment programmes that target women do not always work and may in fact cause harm due to male backlash (Schuler, 2005; Gibbs, Jacobson, and Kerr Wilson Citation2017). Similarly, there is an understanding that making women aware of gender inequality is not sufficient for transforming gender norms. Changing practices within homes and the larger community are pertinent for large-scale behaviour change. In fact, over the last decade programmes such as SASA! (Abramsky et al. Citation2014) and Stepping Stones (Jewkes et al. Citation2008) have gained prominence for their effectiveness in transforming community norms around gender-based violence through group discussions and critical reflection. Also, factors such as lack of male support and reproductive coercion can prevent women from using contraceptives or make them use it covertly and fear retribution. Very few programmes attempt to transform deeply rooted gender norms as well as target multiple structural drivers simultaneously that make them so pervasive and immutable, and tend to focus one or the other. The small body of evidence that is emerging in this arena suggests that such an approach can prove to be an effective strategy for transforming gender relations (Kerr-Wilson et al. Citation2020). This intervention by targeting three interdependent sites of women’s disempowerment, while working with couples for sustainable change, fills a critical gap in our understanding of how to foster sustainable gender equity within households.

The programme comprised three-layered interventions: (1) gender socialisation and relationship training, (2) financial literacy and household budget management, (3) couples' counselling on modern contraceptive methods with vouchers available for couples in the poorest quintile to obtain a method of their choice, should cost be a barrier. Given that the main goal of the programme was to reduce gender-based power differences between spouses, gender socialisation and relationship training was considered the main intervention. We hypothesised that the intervention by building critical awareness around harmful gender norms, generating empathy between partners, and enhancing conflict management and communication skills, would foster greater female participation in decision-making within the household and reduce gender-based power differences. We also hypothesised that the other interventions by building financial knowledge and budget management skills, and counselling couples on contraceptive methods, would foster greater female participation in financial decision-making and greater spousal collaboration in the reproductive arena.

Study context

In Nigeria, despite growing influences of modernisation and westernisation, women continue to tackle a patriarchal culture, which relegates their position within the household and limits their capacity to exercise choice and agency in their lives. Household division of labour continues to follow traditional gendered roles, with the male partner being the breadwinner and decision-maker, while women are ascribed tasks within the household. These traditional roles often disempower the woman such that she has no say regarding how household funds will be spent and inhibit her from making important household decisions such as whether or when she can have children, or when she and her children can receive preventive, curative, or rehabilitative healthcare (Klugman et al. Citation2014). Moreover, in Nigeria, both the customary law and the major religions stipulate that a woman should be submissive to her husband.

Methods

Study design

We utilised a four-arm cluster randomised control design to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention. In arm 1, the couple received a structured group education programme on gender socialisation (GS arm). In arm 2, the couple received a structured financial literacy education programme, in addition to the programme on gender socialisation (GSFL arm). In arm 3, the couple received the complete package of intervention that includes gender socialisation education, financial literacy education, and family planning counselling with vouchers for the poorest women to secure a method of their choice (ALL arm). Arm 4 served as the control group.

The study received ethical approval from the University of Ibadan’s Research Ethics Committee as well as administrative approval from the Medical Officers of Health of each of the four local government areas where data were collected before couple recruitment commenced. The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT03888495).

Study population

Women and their spouse/partner were recruited from 48 different communities in two urban (Ibadan North, Ibadan Southwest) and two peri-urban (Akinyele and Oluyole) Local Governments Areas (LGAs) between September 2017 and July 2018. To be eligible for the study, women had to be between 18 and 35 years old and currently residing in the same household with their spouse or long-term partner in any of the selected communities in Ibadan, Nigeria. There were no age restrictions for men who were in a union with eligible women.

Randomisation

An independent statistician conducted block randomisation with stratification, using a block size of 4, with the cluster as the unit of randomisation (Kim and Shin, Citation2014). The four LGAs served as strata. All 48 clusters (12 per LGA) were randomly allocated into one of the four study arms. Cluster randomisation rather than individual randomisation was considered appropriate for this study because members of a community are often similar in many ways, and cannot be considered to be independent of one another, especially with respect to socially determined behaviour. Group assignment was not masked for participants or members of the study team, given the nature of the study.

Study participants were selected through a three-stage randomisation process. First, geographical landmarks/boundaries were used to divide the 11 LGAs (5 urban, 6 peri-urban) in Ibadan into two roughly equal halves. Then one urban and one peri-urban LGA were selected randomly from each half, using the random number generator application (Available on Google Play Store), giving a total of four LGAs. Secondly, using a map of each of the four selected LGAs displaying localities, alternate distinct localities were selected in a serpentine fashion, following a random start. This was to ensure that 12 geographically distinct clusters are selected, and to minimise contamination bias. Using a sampling frame of enumeration areas by locality in each of the four LGAs (National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International, Citation2014), one index enumeration area, and its adjoining enumeration area with a higher code were randomly selected to form study clusters. Where a sufficient number of couples could not be recruited from these two enumeration areas, the cluster was expanded to geographically adjacent enumeration areas. Lastly, household-listing surveys were conducted in the selected EA clusters to enable identification and recruitment of eligible couples, ages 18–35 years, per study arm to participate in the study. In general, where more than 26 eligible couples were listed in a given cluster, systematic random sampling, following a random start, was used to select couples for the baseline interview. Couple selection only took place once, at the beginning of the study.

Study interventions

The intervention took place over a 6-week period from July 28 to September 8, 2018, starting almost immediately after baseline interviews were completed. The intervention focused on building knowledge, awareness, skills, and critical consciousness, as well as enhancing access to services. The first study arm (GS Arm) received gender socialisation training, which was focused on building awareness and critical consciousness on gender roles and norms, power, division of labour, as well as skills building on decision-making, conflict management, negotiation, and communication. In Arm 2 (GSFL), in addition to GS training, the participants received three sessions on financial literacy and household budget management. The topics discussed included an introduction to important financial terms (like savings, loans, investments, assets, income, expenditure) and how to undertake financial planning, manage money, and access financial services. The training also built skills around financial decision-making and household budgeting. The training sessions for GS and FL were contextually adapted from relevant existing materials obtained through consultation with experts in the field, as well as a search of the literature. Each session was 2 h long and they were offered weekly. While some sessions were intentionally gender-disaggregated, others brought the couple together, particularly sessions that focused on skills-building. All training sessions were led by a facilitator, and included individual and group activities, as well as role play. Facilitators were carefully selected by the study team, had at least a bachelor’s degree, and possessed the soft skills needed to implement the programme and manage participants. They received a four day training on the components of the intervention, and weekly refresher training sessions throughout the length of the intervention. Supervisors were available to support intervention training sessions. The third intervention arm received couple counselling on family planning, in addition to GS and FL training. The FP session was 2 h long and led by a family planning nurse that had been trained by the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative and using the Balanced Counselling Strategy (BCS) approach. The content of the family planning session was the same as the counselling offered by nurses in family planning clinics in Ibadan, Nigeria, where the study took place.

Study outcomes

Decision-making

We assessed three critical domains of household decision-making – general household decision-making, financial decision-making, and reproductive decision-making. The measures were more nuanced than the standard questions routinely asked in demographic and health surveys. Respondents were asked “how involved they were in decisions pertaining to an area” as opposed to “who makes the decisions” asked in routine surveys. Respondents could choose from five response categories: (1) Not involved, I provide no input; (2) I give my input, but my partner makes the final decision; (3) We discuss and decide jointly; (4) My spouse provides input, but I make the final decision; (5) I make final decision without my spouse’s input. These response categories were included to capture variation in levels of spousal participation and reduce the pooling of responses in the joint category, so that category that captured “joint” is closer to a more collaborative decision-making process and does not just disguise male control.

General household decision-making was assessed with six items pertaining to decisions around visiting family/friends, caring for children, accessing health services for self-health, household expenditure on food, household expenditure on clothing, and expenditure on major household purchases. Financial decision-making was measured by two items focused on decisions pertaining to how the household would use its savings, and what investments would be made with household income. Reproductive decision-making was evaluated with two items that assessed involvement in decision to use (or not) contraceptive methods and planning the number and spacing of birth. In alignment with our hypotheses, for general household and financial decision-making, the item scores were recoded such that a higher score indicated greater female participation in decision-making. Similarly, for reproductive decision-making, the items were recoded to reflect higher scores for joint decision-making. Each of the sub-domains were assessed for internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha and indices were created by implementing Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Alpha levels of all three scales were over the recommended threshold of 0.60, with 0.68 for household decision-making scale, 0.72 for financial decision-making, and 0.97 for reproductive decision-making. The predicted values from the PCA were re-scaled to range from 0 to 100 for ease of interpretation where a higher score indicates greater female participation in general household and financial decision-making, and more collaborative decision-making for the reproductive domain.

Earnings

In addition to these indices, we assessed women’s level of participation in the use of her own and her spouse’s earnings separately. The score ranged from 0 to 3 and a higher score indicated greater female participation.

Sample-size determination

The minimum sample of study participants in each arm of the study assuming a fixed number of clusters was calculated for a few key measures including participation in household decision-making (Hemming et al. Citation2011) using raw data available for Oyo state from the Nigeria Demographic and Health survey conducted in 2013 (National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International Citation2014). We assumed the intervention would improve key outcomes by 15%. Assuming 80% power, a two sided type 1 error of 5%, and the proportion of married/cohabiting women ages 18–35 years who were involved in decisions regarding large household purchases to be 0.275, 225 participants in each arm were required. An intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.015 was assumed in the calculations, as well as a fixed number of clusters of 12 per arm (48 in all). Adjustments for 20% loss to follow up rates give a total of 282 couples per study arm. Calculations based on the above assumptions gave a minimum sample size of 1125 couples.

Study data collection

Baseline interviews, using paper-based structured questionnaires took place concurrently with recruitment, and were conducted from September 15, 2017, to July 10, 2018, prior to randomisation of clusters, and concurrent with study recruitment. Couples were interviewed in a public hall (within a school, local government headquarters), or the hall of a hotel within their community, or in their homes. Halls were rented with the goal of improving visual and auditory privacy, but many couples preferred to be interviewed at home. Women and their partners were interviewed at the same time by gender-matched field staff who worked together in pairs. If one member of the couple was not available, we asked for a more convenient time to return. This often resulted in multiple visits, and most successful interviews were conducted on weekends and holidays, or late in the evening, given the difficulty in meeting men at home during the day, especially on weekdays.

Following baseline interviews and randomisation, interviewers returned to the field to inform couples of the study group their cluster was randomised to. Endline interviews were conducted for couples in all four study arms, six months post-intervention. All interviews were gender-matched to the interviewer. All efforts were made to ensure auditory and visual privacy, though the latter was often challenging. However, interviews were rescheduled where auditory privacy was not possible. Efforts were made by interviewers to reach all couples who had been interviewed at baseline, even if they had moved outside of the community, provided they still resided within the city of Ibadan. Two couples who had moved outside of the city elected to be interviewed in their former communities on a weekend they had planned to be in Ibadan.

Study retention

At baseline, we recruited 1236 couples who met eligibility requirements, out of which we were only able to interview 1064 couples, 16 men and 16 women at endline. Loss to follow up was due to the following reasons: (1) Inability to find participants in their residence, (2) Inability to reach participants who were not at home by phone, (3) Unavailability of couple after at least three visits, (4) Having moved outside the city, (5) Refusal, (6) Death. At endline, during the mop-up phase of the survey, we interviewed the available partner if we were unable to track the other partner after more than three attempts.

Statistical analysis

Difference-in-Difference (DID) models based on a linear specification are used to assess the impact of the programme by comparing changes over time in intervention arms compared to the control arm. This approach identifies programme impact as the difference in the change observed in an outcome between participants and non-participants over the interval of the programme. A key assumption being that in the absence of the treatment, the difference between the intervention and control group would be constant over time or the “trend” of change would be the same in the groups. DID is implemented as an interaction term between time and treatment group dummy variables in a regression model and can be specified as follows:

The models were adjusted for clustering as well as covariates that were unbalanced between the intervention and control arm.

Results

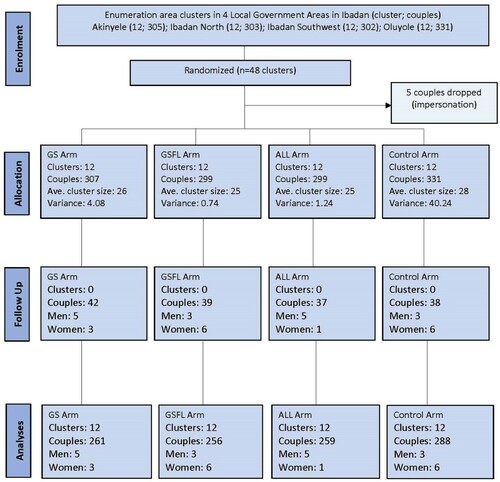

The final sample consisted of 1064 couples, with a loss-to-follow up of 14% between baseline and end line (). We assessed for systematic differences in key demographic characteristics and key outcomes between the final intervention sample and the lost-follow up. The two samples were comparable but for a couple of demographic characteristics. The women in the lost-to-follow-up sample were more likely to be less educated and belong to a non-Yoruba ethnic group.

Baseline characteristics are shown in . While the groups were balanced in demographic characteristics such as age, number of children, and levels of polygamy, there were significant differences in some features. On average, women were 29 years old, and nearly 50% had one or two children. Over 50% of the sample across the arms followed Christianity. However, the GS (60.61%) and GSFL (61.07%) arms had significantly higher proportion a of Christians as compared to the control group (53.06%). Similarly, the GSFL arm had a slightly lower proportion of Yorubas (75.57%) and a more diverse ethnic profile as compared to the control group (82.31%). Lastly, women in the GS and GSFL arms were more likely to have higher education as compared to the control group.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample at baseline.

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables by time are shown in and . While there were declines in female participation in general household decision-making and decisions around how husbands’ earnings will be used in the control arm, the trends were positive in all decision-making areas for women in the intervention arms. Although female participation in the reproductive and financial arena was showing positive trends across the groups, apart from reproductive decision-making in the GSFL arm, women in the intervention groups had greater improvements in these arenas than women in the control arm.

Table 2. Baseline and endline levels for decision-making domains by intervention arms.

Table 3. Change in decision-making scores between baseline and endline by intervention arms.

Results from the difference in difference regression models can be found in . In the models adjusted for clustering and covariates, the coefficients for general household decision-making were statistically significant at the 0.05 Alpha levels only in the arm that received all three interventions. The coefficients in the other arms trended in the positive direction but were only marginally significant (0.1 Alpha level). Women’s participation in general household decision-making increased by about six percentage points [β: 6.18 (SE: 2.74)] in the arm that received all three interventions, the other arms also saw similar increases but were not statistically significant. Similarly, participation of women in decisions pertaining to husbands’ earnings also only increased significantly in the arm that received all three interventions as compared to the control group, while these improvements were marginally significant in the other two intervention arms. Statistically significant improvements in female participation in financial decision-making were noted only in the GSFL arm, with increases of over five percentage points, compared to the control arm. While two of the intervention arms showed improvements in spousal participation in reproductive decision-making, including the arm that received the family planning intervention, the coefficients were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Difference in difference estimates of programme impact on decision-making domains.

Discussion and conclusion

Overall, the impact of the intervention and its components on shifting decision-making patterns within the household were mixed. While positive increases in general household decision-making and decisions regarding use of husbands’ earnings scores were seen in the three intervention arms as compared to the control arm, the results were significant only in the arm that received all three interventions, and only marginally significant in the GS and GSFL arm. Similarly, financial decision-making scores significantly improved only in the GSFL arm, were marginally significant in the GS arm, and non-significant in the arm that received all three interventions. Although, clearly, these inconsistent results point to the need for additional research and adaptation of the programme, the trend appears to be positive, particularly in areas where women continue to be less active such as general household and financial decisions, as well as decisions pertaining to use of men’s earnings. However, the programme seemed to be clearly ineffective in areas where the trend appeared to already be moving towards increased female or joint decision-making, such as reproductive decision-making and use of women’s earnings. These inconsistencies in the results could also be indicative of weakness in our decision-making measures. While we tried to include a larger number of response options to reduce the tendency for answers to lump around joint decision-making, our sub-components of various decision-making domains, drawn from previously validated measures such as the demographic and health surveys, may have missed important context specific sub-domains. Hence, failing to appropriately measure the myriad ways women may have exercised agency within their constrained environment. This again highlights the need for investments in qualitative research as well as development of context-specific decision-making measures.

With regard to programme components, the general trend in increases in general household decision-making and participation in decisions pertaining to husbands’ earnings suggests that, as hypothesised, the gender socialisation component may have been most critical as it most directly tackled the underlying gender norms and inequalities that hamper women from participating in household decision-making. The components' emphasis on building critical awareness around gender and power differentials as well as providing couples with the tools and skills to enhance communication, build trust, and manage conflict and negotiations, enabled couples to create safe spaces within their homes, where women felt their opinions were valued and respected. With these findings, our study adds to knowledge on how couple-based gender transformative approaches for improving health and development outcomes for women and their households by fostering greater equality and improving relationship quality might be promising (Darbes et al. Citation2014; Doyle et al. Citation2018).

The conflicting results also raise questions on the value of layering economic and reproductive components onto a gender-transformative intervention. While we did not statistically test for differences between the intervention arms, the trends do not indicate any clear benefits of layering the different intervention components. We speculate that this may have to do with the shorter duration of programme activities as well as the nature of programme content in the financial literacy and reproductive components, the primary emphasis of the programme being the gender socialisation intervention. As opposed to the gender socialisation curriculum, the curricula in the other two components were primarily focused on content and increasing knowledge around financial services and family planning methods, and less emphasis was placed on skills building and/or critical reflection. An added challenge for the financial literacy arm, we suspect, could have been the difficulty in comprehending study materials and/or transitioning from learning to using financial services. Prior research suggests that financial inclusion services assume universal literacy and a certain degree of numerical skills, which may not always be viable, particularly in “oral cultures”, where women often predominate (Matthews Citation2019). While prior research has, overall, seen positive trends in layered programmes with gender transformative components, there have been instances of mixed findings (Gibbs, Jacobson, and Kerr Wilson Citation2017). We do believe there is potential in these additional components, but the intervention components need to be more comprehensive with a focus on knowledge, critical reflection, and skills building, along with linkages with services. Future research should examine how a more comprehensive approach performs.

Our study is unique in its focus on improving women’s decision-making ability within the household by transforming gender relations as well as providing tangible skills, such as financial literacy and knowledge of modern contraceptives, which also provided an incentive for participants to attend the sessions. It was rigorously evaluated using a cluster randomised control trial and reached over a 1000 couples. Despite its strengths, there are a few limitations that need discussion. We were unable to mask group assignment from participants. The key measures were self-reported and therefore prone to social desirability bias. The follow-up time was limited to six months, which was not enough to assess sustainability of behaviours. Our findings are not generalisable beyond the population of urban Ibadan and similar settings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Funmilola M. OlaOlorun

Funmilola M. OlaOlorun is a community health physician and holds a PhD in Public Health from the Department of Population, Family & Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD. She is currently a senior lecturer in the Department of Community Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, and an honorary consultant to the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Her research focuses on women's health across the lifecourse, from adolescence to menopause. More specifically, she is interested in professional support for breastfeeding, women's involvement in household decision-making, family planning, intimate partner violence, and experiences at menopause.

Neetu A. John

Dr. Neetu John is an Assistant Professor of Population and Family Health at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. She specializes in Population and Reproductive Health and has worked for over a decade in Africa and Asia. She applies an interdisciplinary lens to understand how gender and other structural inequalities impact health and development outcomes, and designs and tests programmatic and policy solutions to resolve the inequities. She has designed and implemented complex research studies such as randomized control trials and impact evaluations, nationally representative population-based surveys, and qualitative studies. Her work explores inter-linkages between issues such as women's empowerment, gender-based violence, household dynamics, care work, spousal relationship quality, child marriage, reproductive and economic empowerment in low and middle-income countries.

References

- Abramsky, T., K. Devries, L. Kiss, J. Nakuti, N. Kyegombe, E. Starmann, … L. Michau. 2014. “Findings from the SASA! Study: a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Impact of a Community Mobilization Intervention to Prevent Violence against Women and Reduce HIV Risk in Kampala, Uganda.” BMC Medicine 12 (1): 122.

- Berniell, M. I., and C. Sánchez-Páramo. 2011. “Overview of Time-use Data Used for the Analysis of Gender Differences in Time Use Patterns.” Background Paper for the WDR 2012.

- Canning, D., and T. P. Schultz. 2012. “The Economic Consequences of Reproductive Health and Family Planning.” The Lancet 380 (9837): 165–171.

- Darbes, L. A., H. van Rooyen, V. Hosegood, T. Ngubane, M. O. Johnson, K. Fritz, and N. McGrath. 2014. “Uthando Lwethu (‘our love’): A Protocol for a Couples-Based Intervention to Increase Testing for HIV: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trials 15 (1): 1–15.

- Doyle, K., R. G. Levtov, G. Barker, G. G. Bastian, J. B. Bingenheimer, S. Kazimbaya, A. Nzabonimpa, J. Pulerwitz, F. Sayinzoga, V. Sharma, and D. Shattuck. 2018. “Gender-Transformative Bandebereho Couples’ Intervention to Promote Male Engagement in Reproductive and Maternal Health and Violence Prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” PloS one 13 (4): e0192756.

- Eerdewijk, A. V., F. Wong, C. Vaast, J. Newton, M. Tyszler, and A. Pennington. 2017. A Conceptual Model of Women’s and Girls Empowerment. Amsterdam: KIT Royal Tropical Institute.

- Finlay, J. E., and M. A. Lee. 2018. “Identifying Causal Effects of Reproductive Health Improvements on Women's Economic Empowerment Through the Population Poverty Research Initiative.” The Milbank Quarterly 96 (2): 300–322.

- Gibbs, A., J. Jacobson, and A. Kerr Wilson. 2017. “A Global Comprehensive Review of Economic Interventions to Prevent Intimate Partner Violence and HIV Risk Behaviours.” Global Health Action 10 (sup2): 1290427.

- Hemming, K., A. J. Girling, A. J. Sitch, J. Marsh, and R. J. Lilford. 2011. “Sample Size Calculations for Cluster Randomised Controlled Trials with a Fxed Number of Clusters.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11: 102. https://nam12.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-102&data=04%7C01%7Cprakash%40com%7Cd234aeeeba8343d510e608d931c082be%7Ca03a7f6cfbc84b5fb16bf634dbe1a862%7C1%7C0%7C637595525182787903%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C1000&sdata=HCcDmFpl4%2BDbjferaQRkuJpxa/BqdUWdOg66Jj0%2B6ak%3D&reserved=0

- Jewkes, R., M. Nduna, J. Levin, N. Jama, K. Dunkle, A. Puren, and N. Duvvury. 2008. “Impact of Stepping Stones on Incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and Sexual Behaviour in Rural South Africa: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial.” Bmj 337: a506.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464.

- Kerr-Wilson, A., A. Gibbs, E. McAslan Fraser, L. Ramsoomar, A. Parke, H. M. A. Khuwaja, and Rachel Jewkes. 2020. A Rigorous Global Evidence Review of Interventions to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls, What Works to Prevent Violence among Women and Girls Global Programme. Pretoria.

- Kim, J., and W. Shin. 2014. “How to do Random Allocation (Randomization).” Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery 6 (1): 103–109.

- Klugman, J., L. Hanmer, S. Twigg, T. Hasan, J. McCleary-Sills, and J. Santamaria. 2014. Voice and Agency: Empowering Women and Girls for Shared Prosperity. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Malhotra, A., and S. R. Schuler. 2005. “Women’s Empowerment as a Variable in International Development.” Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives 1 (1): 71–88.

- Mannell, J., S. Jackson, and A. Umutoni. 2016. “Women's Responses to Intimate Partner Violence in Rwanda: Rethinking Agency in Constrained Social Contexts.” Global Public Health 11 (1–2): 65–81.

- Matthews, B. H. 2019. “Hidden Constraints to Digital Financial Inclusion: the Oral-Literate Divide.” Development in Practice 29 (8): 1014–1028.

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2014. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja: NPC and ICF International.

- Richardson, R. A. 2018. “Measuring Women’s Empowerment: A Critical Review of Current Practices and Recommendations for Researchers.” Social Indicators Research 137 (2): 539–557.

- Schuler, S., S. Hashemi, and A. Riley. 1997. “The Influence of Women’s Changing Roles and Status in Bangladesh’s Fertility Transition: Evidence Form a Study of Credit Programs and Contraceptive use.” World Development 25 (4): 563–575.

- Schuler, S. R., and S. M. Hashemi. 1994. “Credit Programs, Women's Empowerment, and Contraceptive use in Rural Bangladesh.” Studies in Family Planning 25 (2): 65–76.

- Sonfield, A., K. Hasstedt, M. L. Kavanaugh, and R. Anderson. 2013. The social and economic benefits of women’s ability to determine whether and when to have children.

- United Nations. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals accessed at https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ on October, 2020.