ABSTRACT

This article provides insights into a decade long process of evidence production and use in support of the Government of Ghana’s adoption of the Complementary Basic Education (CBE) program for out-of-school children. A review of existing evidence on the program and our semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders revealed the centrality of the government’s culture of evidence-informed policy making. Our findings also highlight the importance of both formal and informal relationships between key stakeholders and the often-neglected significance of civil society in evidence production and uptake, leading to a modification of Hinton et al.’s policy impact framework.

1. Introduction

Non-governmental organisations have played a key role in providing complementary education programs to reach out-of-school children across the globe. These aim to enable children who have never been to school or dropped out due to factors such as poverty, gender, and rural status to gain basic literacy and numeracy skills (Shinohara Citation2021). To address challenges these children face in accessing formal schools, complementary education programs are often located closer to homes in rural areas with flexible schedules to accommodate household and other work needs. They usually involve communities and collaborations with government and non-government partners in their delivery (Rose Citation2009) and commonly raise learning outcomes (Shinohara Citation2021). Once a successful approach for local implementation is established, funders often hope governments will adopt the provision, and so increase their scale through domestic financing, but this rarely happens (Carter et al. Citation2020a). As such, the programs frequently continue to rely on external donor funds that can be subject to change at short notice and may lack the local ownership that is essential for sustainability.

This paper focuses on the role that evidence can play within the policy process, with a focus on the Government of Ghana’s recent government adoption of the Complementary Basic Education (CBE) program. It recognises that the role of evidence needs to be considered in the context of broader political, financial, and social motivations that shape policy reforms. For example, Carvalho, Asgedom, and Rose’s (Citation2022) exploration of stakeholder negotiations in the design of education reforms within Ethiopia revealed that government and donors occupy the primary “policy bargaining space” with the former leveraging their political influence over priorities during the process and the latter more their financial and social influence. This research, which is applicable to a number of contexts in the Global South, found the policy process to be characterised by ongoing negotiation and compromises between key actors involved and that local actors (e.g. civil society organisations [CSOs], regional government) were largely left out.

The CBE program in Ghana is a particularly interesting case study for analysing the role of evidence in government adoption of a successful reform implemented by CSOs. Over the past 25 years, CBE programs have been entirely run by CSOs with external funding from international aid donors. CBE programs enable fast and deep self-efficacy amongst learners and achieve in less than a year what three years or more of public education achieve (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018). In 2018, the Government of Ghana announced its intention to implement the CBE program. In order to explore the role of evidence in this process, we reviewed grey and published literature on CBE and undertook key informant semi-structured interviews to identify donor, government, CSO and researcher relationships in the translation of research to policy uptake, drawing on Hinton, Bronwin, and Savage’s (Citation2019) Pillars of Policy Impact framework. Through analysis of these interviews, this paper reveals the often-neglected significance of CSOs in the production and communication of evidence. It also highlights the centrality of the Government of Ghana’s culture of evidence-informed policy that has been crucial for the adoption and scaling of the program.

1.1. Background to Ghana’s CBE program

Initially referred to as the School for Life (SfL) project, CBE began in 1995 as a small educational innovation for out-of-school children in two rural districts in the northern region (Hartwell Citation2006). Ghanaian and Danish CSOs known as the Ghana Developing Communities Association and the Ghana Friendship Group established SfL. During its early years, SfL worked in close partnership with the Ghana Education Service Ministry of Education and the Dagbon Traditional Council (SfL Citation2017).

From 1995 to 2006, DANIDA was the primary funder of SfL, and this support has continued to date (SfL Citation2017). In 2006, USAID became a second key donor, enabling the program to expand into nine districts. The UK Department for International Development advisor (DFID, now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office – FCDO), identified the initiative as effective following a joint visit with the National Audit Office in 2010. DFID investment began in 2012, enabling expansion to around 40 districts. Since that time, DFID became the primary funder of the initiative, which was referred to as the Complementary Basic Education (CBE) program. DFID’s investment was conditional on the Government of Ghana leading the work within their Basic Education Unit.

Since 2013, the CBE program has expanded to ten CSOs (known as implementing partners) with support from an External Management Unit (composed of the not-for-profit business Crown Agents and the research and consultancy firm Associates for Change). These partners support the Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service to implement CBE at the district and community level. By 2018, CBE had assisted over 250,000 of Ghana’s poorest children, approximately half of whom are girls, in around 6,000 communities. CBE has focused on the provision of learning basic literacy and numeracy skills in mother tongue, using local facilitators. The ultimate goal of CBE is to enable a smooth transition of children into government schools upon completion of the nine-month program (DFID Ghana Citation2018).

1.2. Evidence on the CBE program

Over the lifespan of the CBE program, there have been numerous studies examining different aspects of the approach (Annex 1). While many of these have been commissioned and funded by donors of the program such as DFID UK and USAID, in all cases, studies have been conducted by independent researchers, i.e. the arguments in the publications are based on the analysis of the researchers, and do not necessarily reflect the view of the donors who do not necessarily have editorial oversight over them.

In respect to studies assessing effectiveness, the first of these – presented as a case study and funded by USAID – found that over a seven-year period, 50,000 students had been enrolled in the SfL program within the northern region. Of these students, 91 per cent were found to complete SfL with 66 per cent transitioning into formal school (Hartwell Citation2006). Following this case study, was an independently conducted impact evaluation also focused on SfL. It revealed that 85,000 children and over 4,000 rural communities across 12 districts had accessed the program within Ghana’s northern region over a 12-year period (Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007). Aligning with earlier research, 90 per cent of children had completed the program and acquired functional literacy skills, with close to 70 per cent continuing their education in the government system. Additionally, this evaluation showed that SfL made impressive strides in tackling gender inequality through bringing about attitudinal shifts in parents about the importance of educating girls. Early research has also investigated the cost-effectiveness of the model (DeStefano et al. Citation2007). This found that, based on the schooling costs for a student who has a Grade 3 or 4 ability level, the approach was more than four times as cost effective as government schools. Other research has focused on the role of SfL as a non-state provider. This identified its potential for providing lessons to improve standard approaches to government schooling by increasing key inputs, including instructional time and materials and altering incentives to bring about teacher behaviour change, such as by providing community recognition and regular supervision of instruction (DeStefano and Schuh Moore Citation2010). In drawing on secondary data, Casely-Hayford and Hartwell (Citation2010) further investigated the challenges non-state actors including SfL face in the provision and financing of CBE. This study found that greater interaction between these stakeholders and government was needed, especially in rural areas, in order to realise the goals of the initiative. In addition, Mfum-Mensah (Citation2011) examined the collaborative nature of the model amongst partners involved in its implementation, such as SfL, facilitators of the program from the local community, and government officials, revealing a number of direct benefits for stakeholders. These included a supportive network and development of new knowledge and skills for government officials who remarked that working with SfL helped them to learn innovative approaches for involving the local community in initiatives and decision-making processes related to the improvement of education.

Another study conducted by researchers at the Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast in Ghana (2015) and funded by UNICEF examined the effectiveness and capacity building needs of National Service Personnel and the National Service Secretariat from Ghana in implementing and scaling up CBE. While this study concluded that both stakeholder groups had “high potential” to effectively conduct and subsequently scale up the model, a number of challenges emerged for members from both organisations. For example, National Service Personnel were found to experience difficulties accessing hard to reach areas where CBE is carried out due to poor road networks and limited accommodation within communities, whereas the National Service Secretariat faced difficulties with identifying CBE facilitators who had the appropriate local language skills needed for classroom instruction.

Following DFID’s funding of CBE in 2012, further evaluations were commissioned to examine the effectiveness of the program. These included a tracer study, which found that 95 per cent of men and women graduates successfully transitioned into formal school and remained there four years after CBE completion (Carter, Sabates, and Rose Citation2018). A two-year longitudinal study examined the educational trajectories of CBE students from the 2016/2017 academic year (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018). The analysis compared CBE children’s learning progress with non-CBE children already within the formal education system, demonstrating children’s successful transition and adaptation to formal school. It revealed the importance of local volunteers as teachers where observing learning success amongst their own communities was a motivating factor in the commitment to quality teaching.

While the evidence from these evaluations overall highlights CBE’s success in improving learning and supporting transitions into formal schools, recent studies have indicated some challenges for particular groups of children. For example, Carter et al. (Citation2020a) estimated transitions into a different language of instruction by program graduates and found that those who transitioned into an unknown language were more likely to decline in their academic performance relative to students who transitioned into a similar language. This issue was also found to be exacerbated by the extent of difference between the language taught within CBE and that taught within formal school (see Daly, Carter, and Sabates Citation2022). Other recent studies have found that low-performing girls do not benefit to the same degree as their peers from the CBE program (Akyeampong et al., Citation2022; Carter et al. Citation2020b). Related to this, Casely-Hayford, Ghartey, and Agyei-Quartey (Citation2021) identified that the effects of the program on girls’ education is contingent on many factors including whether a woman is a head of the household and if parents themselves have an education.

1.3. Conceptual framework: processes for evidence to lead to policy change

The pathways from evidence to its uptake and impact on policy is far from straightforward. Processes leading to the uptake of evidence are often two-way: policy actors demand evidence, and researchers supply relevant evidence in an accessible way. It further requires both policy actors and researchers to have the motivation and time to build relationships to ensure this demand and supply of evidence is met (Georgalakis and Rose Citation2019: Oliver and Cairney Citation2019). As Georgalakis and Rose (Citation2019) identify, such partnerships are most likely to be successful where actors are driven by a mutual agenda, where there is sustained interactivity between them, and where researchers are able to act and adapt swiftly as policy windows emerge.

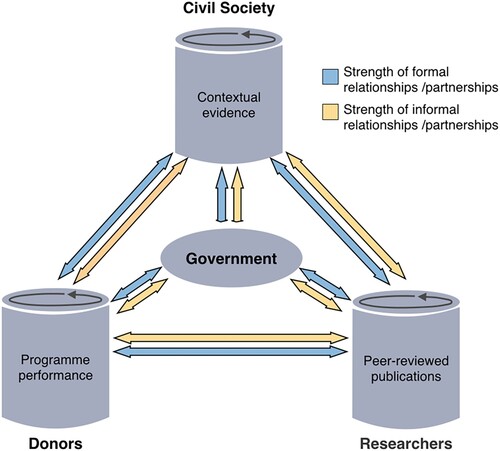

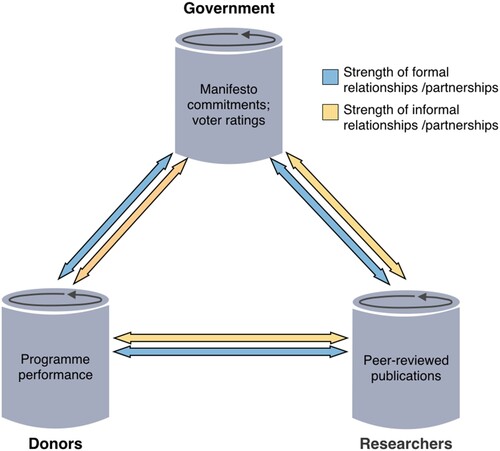

The influence of evidence on policy change is also likely to benefit from partnerships between different types of stakeholders. For our analysis, we adopt the Pillars of Policy Impact conceptual framework developed by Hinton, Bronwin, and Savage (Citation2019). The framework emphasises the potential importance of both formal and informal partnerships between donors, researchers and government as pivotal to achieving research uptake (see ). Through country case studies, Hinton et al. identify the key role of donors as “knowledge brokers” and “translators” of evidence, who can help national government, CSOs, and local actors understand and respond informatively to research. As discussed further below, in this study, we emphasise the role of CSOs as essential in the production and communication of evidence and thus consider a potential additional dimension to Hinton et al.’s framework, namely the inclusion of a pillar for CSOs.

Figure 1. The Pillars of Policy Impact. Source: Hinton, Bronwin, and Savage (Citation2019).

2. Research methods

The first stage of our research was to identify participants representing key stakeholders within the pillars of the framework (i.e. researchers, donors, government, and CSOs who have played an important role in the development and government adoption of CBE). See for all 16 participants involved in the study and their affiliated institutions. These stakeholders were identified through an examination of the literature and policy documents, as well as the authors’ own engagement with the program, both as funder and as researchers who have evaluated the impact of the program. It is sometimes difficult to categorise participants according to a single pillar. Notably, Leslie Casely-Hayford has been involved in CBE through working with CSOs, leading consultancy, and research with Associates for Change, as well as supporting the government as a consultant, and so could potentially be included across three of the pillars. For the purpose of this paper, we include her with respect to her main role as researcher and evaluator of the CBE program (see ), while recognising her other roles.

Table 1. Categorisation of interviewees.

Data were primarily collected through semi-structured interviews conducted between November 2018 and March 2019. During interviews, participants were first shown the Pillars of Policy Impact framework to help stimulate thinking and reflection. Interviews lasted between 40 and 60 minutes. In addition to these data, several documents reflecting key stages of CBE’s evolution and/or its impacts were analysed for the purposes of the research. These included research studies and evaluations on the program (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018; Carter, Sabates, and Rose Citation2018; Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007; Casely-Hayford et al. Citation2017; Hartwell Citation2006; Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast Citation2015 – see Annex 1), as well as relevant policy and implementing partner documents (Ministry of Education, Science, and Sport (MOESS) Citation2007; Ministry of Education Citation2013; SfL Citation2017).Footnote1

Ethical approval was received through the University of Cambridge. All participants were asked for their informed consent prior to interviews, if they had any concerns before interviews commenced, and if they had read and understood the provided study information. Participants were also given the chance to withdraw at any time and were provided with the researchers’ contact details if any concerns regarding the study arose. It would have been extremely difficult to anonymise, given the unique role each of the participants played in the CBE process. As such, participants were asked for their consent to be named in the analysis, which they agreed to. Where attribution to quotes is included in the article, these have been confirmed with participants, in accordance with the agreed consent process.

Data were analysed using a direct content analysis approach, the objective of which is to validate or extend a conceptual framework (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Using QSR Nvivo software, the first stage of this method involved developing a broad framework based on Hinton, Bronwin, and Savage’s (Citation2019) categories of stakeholder relationships. Additional themes were created to capture factors, which facilitated the development of partnerships and uptake of evidence. Codes were applied to the transcripts based upon this framework and its associated themes.

It is important to state our positionality with respect to the program. The authors of the paper include a former DFID country advisor in Ghana who potentially has a stake in the findings. The other authors are researchers who were independent evaluators of the program, with funding from DFID. This necessitates reflexivity about potential bias in the research process and analysis (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011). In particular, we recognise that this could raise criticisms of our potential bias in favour of the program. However, the evaluations that had already been completed identified overall consistent evidence of success of CBE, with some caveats for example in relation to language groups and gender, as identified in Section 1.2. As such, this paper does not intend to identify whether or not the program was successful, but rather whether and how the evidence was used to inform the government’s adoption of the program. Our involvement in the program has allowed us to engage critically in assessing this, while also giving us unique access to participants in the process.

Similarly, many of the stakeholders interviewed may well cast a positive light on the program due to their long-standing engagement which could be perceived as a limitation of the study. However, given the focus of the analysis was not to ascertain the impact or otherwise of the program, we feel that these perspectives provide a richness of experience that is valuable to our analysis. It is also often the case that such stakeholders can be critical of whether and how government engages with programs of this kind.

3. Results and discussion

In this section, we present findings relating to each stakeholder relationship relevant to our conceptual framework. Within each subsection, we describe findings related to the history of each partnership, and the ways in which research uptake was facilitated through the partnership.

3.1. Civil society organisations–government relationships

A number of our interviews identified long-standing collaborations between CSOs and government, supporting previous literature on CBE in Ghana (e.g. Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast Citation2015). In CBE’s early stages, for instance, SfL provided support to the Ghanaian Education Service and Ministry of Education through training of teachers in effective pedagogy and addressing staffing issues through training facilitators to enter government schools following CBE involvement. This support was reciprocated through the Ghanaian Education Service providing access to school facilities and support in monitoring CBE classes (Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007, 5). SfL was also actively involved in mainstreaming elements of their program into the formal education system and replicating their model.

Following the scaling up of CBE in 2012 when DFID joined as a funder, CSOs and government, in coordination with the External CBE Management Unit, interacted and supported each other in the provision of basic education for out-of-school children (Casely-Hayford et al. Citation2017). CSOs have helped build government capacities to implement CBE independently through their support in government-led pilot cycles of the program. For example, in the 2013–2014 CBE cycle, 22 government National Service Personnel implemented CBE alongside 83 community facilitators linked with local CSOs (Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast Citation2015). CSOs have also worked with government to help shape the CBE model and increase its accessibility over time. During his interview, Zakaria Sulemana from Oxfam IBIS Ghana (one of the CBE implementing partners) described how a collaborative, real-time problem-solving approach helped understand and address barriers faced by the Ghana Education Service in reaching out-of-school children:

We had hands on experience together, we worked with them in defining and deepening our understanding of the problems facing hard to reach children. Part of the reason why this relationship was also strong, was that in defining our programs we took into consideration, the constraints faced by the Ghana Education Service at the local level in order to support education and therefore, the CBE program, and factored it into the design of the program.

Strong formal channels to allow for collaboration were highlighted by interviewees as essential to building relationships and enabling research uptake. The establishment of the CBE Steering Committee by the Ministry of Education in 2013 was credited as vital to sharing and application of evidence and the recognition of work of CSOs by government. Chaired by the Chief Director from the Ministry of Education with representation from relevant stakeholders, the primary aim of the committee was to oversee the implementation of CBE across districts in line with the policy framework. According to Leslie Casely-Hayford, the CBE Steering Committee enabled an essential link between the knowledge of implementing partners about what was and was not working with CBE and the Government of Ghana. Charles Otoo, the Team Leader of the External CBE Management Unit, noted that the sharing of evidence at regular review meetings was particularly valuable, a context that helped incentivise implementing partners through acknowledgement of their work and foster a constructive competitiveness whereby those who were performing relatively poorly increased their efforts: He stated:

Where the country directors of all the implementing partners sit around a table and share the results of their programs according to language, according to district. Then if your team is not doing very well it then affects them. So, they then had to put in more effort for supervision.

While advocacy of policy issues by CSOs and their proactivity in producing and applying evidence was noted as having government acknowledgement, their influence in prompting policy debate and change through this medium was seen as less pronounced than other actors. As summarised by Sulemana Osman Saaka, the Program Manager of SfL (a CBE implementing partner):

SfL has fair influence, the CBE External Management Unit has a great influence and development partners have even more influence … Their [the government's] inability to involve us is historical.

Sulemena Osman Saaka also noted that the weaker influence of CSOs over government may be underpinned by government not perceiving all CSOs as legitimate and reliable and that many CSOs are based far from the capital Accra and thus less able to engage regularly with central government. In this regard SfL was viewed as an outlier. SfL had earned respect and influence through its long history of engagement and responsive support, providing government with evidence for decision-making. Other interviews reinforced the view of the relatively weak direct partnership between CSOs and government, compared with other actors, and the important role of intermediaries in connecting these stakeholders.

The External CBE Management Unit was identified as a key intermediary in linking these stakeholders, including through its role providing resources for implementation and technical support for monitoring. The Unit’s Team Leader, Charles Otoo, was viewed as being core to this relationship. His previous work in government as a Financial Controller for the Ghana Education Service helped establish mutual respect, promote ongoing cooperation throughout CBE’s implementation and facilitate communication and engagement with CSOs. Ernest Wesley-Otoo (Head of Planning and Development Partners Coordination Unit of the Ministry of Education) described how his former working relationship with Charles Otoo in government enabled continued coordination between the Ministry of Education, the External CBE Management Unit, and CSOs of the CBE program. Similarly, Professor Kwame Akyeampong, who was responsible for conducting research on the effectiveness of CBE and advising the Government of Ghana based on this evidence, noted that Charles Otoo’s deep knowledge of the Ministry of Education also equipped him with strong political capital whereby he could ask the right questions and identify the right people in relation to what was and was not working with respect to CBE.

3.2. Government–donor relationships

Strong and long-standing government–donor relationships were a salient theme within a number of interviews. Underpinning these relationships was a strong history of mutual agendas. The focus of the second Millennium Development Goal on universal primary education was central to DFID’s support to education, and the Government of Ghana was keen to show national and global leadership to meet it. A manifesto promise of the ruling party at that time, the National Democratic Congress (in power from 2009 to 2016), was to commit to this goal, notably to provide universal access to free primary education. This alignment of agendas made DFID’s appeal to government to partner on the CBE out-of-school program a potentially easy “win”. However, the path for securing genuine government buy-in was not a given, with institutional barriers and hard-to-shift power dynamics affecting the distribution of national resources. There was also a value-based resistance by some government officials to CSOs replacing government as an agent for service delivery, that was felt to be a government responsibility, a view that has been expressed widely in other Global South contexts (see Menashy Citation2016). The presentation of global evidence and the creation of informal convening spaces for the voices of local leaders to be heard were crucial to help shift these deeply held perspectives.

The concept of donors as “knowledge brokers” throughout their long-standing collaboration with government was a recurring theme in interviewee discussions. According to Sulemana Osman Saaka, Program Manager of SfL, while the donors were not directly involved in conducting the research, they enjoyed the most influence with government in terms of its uptake, a position enabled through a shared history of involvement in different programs over many decades, in-country presence as well as consistent involvement in sector meetings. This “seat at the table” is underpinned by the power afforded to donors due to their financial resources.

This influence was suggested within interviews in relation to both DFID’s and USAID’s partnership with the Government of Ghana. With respect to USAID, in 2003, SfL’s program gained recognition from government through the commissioned study by them on “Reaching Underserved Populations with Basic Education”. USAID’s promotion of this work for their Education Quality for All (EQUALL) project led the Ministry of Education to recognise the potential of complementary education as a “potentially viable approach for reaching underserved areas of Northern Ghana” (Casely-Hayford and Hartwell Citation2010, 530).

Showing commitment beyond their own responsibilities was noted as an important quality that helped donors develop trust and informal relationships with government. These factors were also confirmed by the donors themselves, who cited their position as a bilateral donor, country embeddedness, history, and persistence as key to their influence with promoting research within the Ministry of Education. As stated by the DFID Advisor, Janice Dolan:

DFID built respect with government through a combination of the research and working alongside government. DFID was seen as a partner who supported, listened, and shared best practice. That built the respect.

DFID’s role was also noted as essential for strengthening formal channels within government to provide a space for research discussion and keeping the evidence “live”. Access to a global evidence base through an experienced advisor was also valued. In describing this “broker” role, the government’s respect for the researchers was highlighted as a means for facilitating access and ongoing technical dialogue. As stated by Janice Dolan:

The research teams often couldn’t get access to the Ministry … The day-to-day engagement DFID could get access. Kwame had the respect. I had confidence in the research – and so I was able to engage and speak about it confidently and facilitate access. Academic names opened the doors – but we were often needed to get the meetings set up and make the research relevant to the current context and priorities of the Ministry.

3.3. Government–researcher relationships

With respect to government–researcher relations, the long-term engagement between Ghanaian researchers – notably, Professor Kwame Akyeampong – and the government ensured that, despite changes in political regimes, trust and respect were built professionally and personally. Akyeampong noted that one of the drivers of this successful relationship with government was the creation of joint research and the building of formal and informal networks for influencing government.

Complementing these historical connections with leading researchers was a strong culture of evidence within the Government. Central to developing this culture, particularly in terms of improving government’s capacity to recognise, apply, and demand meaningful research, was a key group of civil servants with a background in research. For eight years, a select group of Ministry officials attended education higher degree programs at Sussex University. Another critical player in this regard was Ernest Otoo, who received training from UNESCO’s International Institute of Educational Planning, and believed that this personal immersion in the issues of evidence production was critical to the government’s overall culture of evidence-informed policy making. The DFID advisor Graham Gass witnessed this first-hand: “Ghanaian policymakers were open to evidence, both the context-specific evidence on SfL and international evidence on what works.”

According to documentary evidence and participant interviews, the Government’s long-standing respect for academics and evidence was seen as key to achieving research uptake. This was reflected in the crucial role of evidence by Casely-Hayford and Ghartey (Citation2007) in informing the initial CBE policy in 2009. An early government commissioned study, which demonstrated how SfL increased gross and net enrolment rates in formal school, was also reported by Leslie Casely-Hayford in her interview as being key to the policy reform (Basic Education Division 2007; cited in Casely-Hayford and Hartwell Citation2010). Another study revealed that per-pupil costs were critical to the reform process (Hartwell Citation2006). As emphasised by David Balwanz, a consultant for DFID:

The research was key to keeping the program alive. I don't know if support for the program would have continued without good quality evaluation and research. It would have been very difficult to make a strong business case without (i) a good, country-based, evidence base, and (ii) a strong international literature.

According to interviewees such as Akwasi Addae-Boahene (a technical advisor to the Government of Ghana) and Janice Dolan, Akyeampong’s connections and reputation within the Ministry of Education also helped research on CBE “carry weight”. His affiliations with world leading institutions and universities including UNESCO and the University of Sussex helped link the CBE name to international standards and “sell” the model within and outside of Ghana. As stated by Addae-Boahene:

Kwame is well respected by everybody in terms of his knowledge, experience, so because of that he carried weight. They know his level of pedigree; people respect that internationally he is recognised in educational research.

The early delivery of a workshop in 2016 where both government and researchers could establish open lines of communication and develop collective understanding of research objectives was critical to strengthening the researcher–government networks and supporting government to engage with evidence. Akyeampong stated:

Many researchers don’t see it as their job to build the networks for influencing government … I made it clear that the weakest element of the research was the ownership of government and that needed attention … I delivered a workshop to bring everyone together-to see it as a joint research journey. I believe that meeting was key-it was held right at the start. Two months after, the contract was given.

Agenda alignment and incentives were also noted by several interviewees as playing a strong role in the development of research-government partnerships and the government’s uptake of evidence. Addae-Boahene remarked: “The Minister of Education is listening to the evidence because it coincides with his agenda”. According to Akyeampong, the alignment of the research objectives with his own agenda helped to motivate him in his work and building government relationships because he could see the connections beyond CBE and how it might influence policy and education systems more broadly. He stated:

I had a bigger agenda for the use of the evidence than just whether the program had impact. I saw beyond that to how it might add up to systems knowledge. From the global perspective, I wanted to take this further to look at the lessons that could be thought about for improvements to the wider system both in Ghana and beyond.

Adapting communication of research to the specific interests and capacities of government representatives and “using evidence as a conversation” were also identified as factors enabling a deeper engagement from government. Having political intelligence, including understanding the pressures of government and their incentives, as well as recognising individuals who would be most influential in promoting evidence, were further skills outlined as important for effective research–government relationships and research uptake. One such individual, who was uniformly recognised by interviewees as a “Champion of Change” within government was the Chief Director of the Ministry of Education, Enoch H. Cobbinah. Cobbinah, who was also responsible for chairing the CBE Steering Committee, was acknowledged as being particularly receptive to research and proactive with sharing its findings to bring about change and challenge government thinking. As shared by Charles Otoo:

We keep saying that one of the key drivers of change is the Chief Director at the Ministry. He bought into the idea, decided to chair the Steering Committee for the program and had led the process up to now. His personal commitment and drive had led to most of the successes.

3.4. Civil society organisations–donor relationships

Prior to the launch of CBE, CSOs already had an established history of working successfully with donors on the original SfL program. SfL originally implemented functional literacy classes for out-of-school children with DANIDA support from 1995 to 2006. USAID then became the principal donor, with DFID taking on this role in 2012, when the CBE program was established. To assist with the development of the CBE program, SfL provided technical assistance that helped DFID refine learning materials into a standardised format application in the CBE program (SfL Citation2017). The strong record of CSO–donor partnerships was important in enabling the SfL model to secure additional funding for the transition into the larger-scale CBE program. According to interviewees, the history of these relationships allowed for trust, mutual respect, and the development of credibility, which facilitated future engagement.

Evidence demonstrating effectiveness of SfL’s program was critical to the continued donor commitment to CSOs. As noted by the Program Manager of SfL, Sulemena Osman Saaka:

The data was essential for attracting donor’s attention to the program and the interest came when SfL could show the flexible nature of the program and its quick results, in particular, learners’ ability to read within a very short space of time.

DFID facilitated these data to reach government decision makers, by ensuring CSOs had a platform in key meetings to share the potential for the SfL model to scale (Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007). This occurred in 2008, for example, when Ghana hosted the Third Accra High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, an event involving heads of donor organisations, ministers from more than 100 countries and CSOs. Here, evidence from the Impact Assessment (Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007) showing stronger academic performance by SfL students, relative to children in the formal sector, was showcased by SfL, resulting in UNICEF supporting the government to create a draft policy (MOESS Citation2007). In 2013, the Government of Ghana, along with DFID and relevant stakeholders reviewed and finalised the draft policy, which was later approved by the Ministry of Education for implementation (Ministry of Education Citation2013). According to Leslie Casely-Hayford, this document became an essential reference point throughout CBE’s lifespan, ensuring a consistency in implementation for the multiple CSOs involved.

3.5. Civil society organisations–researcher relationships

Since CBE’s inception, CSOs have played an integral role in the production and support of quality research that has helped lead to the government’s uptake of the program. As research was produced, it fed back into iterative cycles of adaption of the program. The relationship between CSOs and research organisations such as Associates for Change, the University of Sussex, and the University of Cambridge has facilitated data collection, analysis, and the production of high-quality, contextualised research outputs.

The production of the SfL impact assessment was a collaborative effort between SfL staff and Associates for Change researchers. This joint effort lasted for over a year, with SfL staff supporting researchers in all aspects of the study including data collection and analysis (Casely-Hayford and Ghartey Citation2007). The quality and strong attention to detail within the Impact Assessment was a key determinant in its uptake by the Government, something that would not have been achieved if it were not for the combination of SfL’s localised knowledge and the researcher’s methodological skills and the close working relationship between them throughout the process. SfL’s close connection to communities helped ensure that participants felt comfortable sharing their experiences, insights which fed back into the program, enabling it to achieve what Casely-Hayford and Hartwell (Citation2010) describe as impressive outcomes and reach.

In the more recent study conducted by the University of Cambridge and University of Sussex to examine the longitudinal impacts of CBE on educational and employment trajectories, SfL was again vital in harnessing local knowledge to support the development of high-quality research outputs. They were instrumental in locating students for this research, informing sample selection, and helping pilot questionnaires that provided essential background data to contextualise achievement findings (Carter, Sabates, and Rose Citation2018). One year later, results from this study became a key focus of a presentation by Professor Kwame Akyeampong to the Minister of Education on the benefits of CBE to out-of-school children’s learning. This research played an important role in the government’s decision to finance and lead on the implementation of CBE, an announcement that came only days after Akyeampong’s sharing of the research findings.

Throughout CBE’s evolution, external academics have worked alongside CSOs to conduct research and produce robust evidence. According to Janice Dolan:

Until local civil society organisations have the required training and research skills, there will be a continued need for the partnership between experienced outside researchers who work alongside them.

3.6. Researcher–donor relationships

The close relationship between researchers and donors throughout CBE’s history was made evident in interviews with Janice Dolan and Kwame Akyeampong. Establishing this partnership, however, was a complex endeavour. According to Akyeampong, when he first came on board there was a “frosty relationship” with DFID, influenced by differing stakeholder views regarding the timing and delivery of prior research projects and mismatched incentives. Improving this relationship and finding common objectives were therefore an initial priority: He stated:

I tried to win trust and gain an understanding of what the donor needed from the research. It was important to build the trust and then decide from there how we would deliver.

For DFID, the primary purpose of research in CBE’s early stages was for initial learning and national lessons. As discussed by Janice Dolan, at the beginning of CBE, there was limited quality information on the learning outcomes or the trajectory of children following completion of the program and, as a funding agency, they wanted to know how well students were doing to “strengthen the narrative”. The expectation was that government would have interest in research due to the value they placed on evidence and interest in “what works” to address national educational issues. While the initial plan had been to carry-out research parallel to the DFID-funded program from 2013, some setbacks were experienced. One key challenge was developing robust research instruments to tight timeframes leading to a lack of baseline data collection and loss of valuable evidence concerning children’s academic development, an issue that was rectified in its second year. Collecting baseline data is challenging and delays like these are common (Bamberger Citation2010; Pritchett Citation2018).

Despite setbacks in CBE’s first year of implementation with DFID funding, research soon became a regular adjunct to the program with coordination and input from key stakeholders. According to interview participants, research on CBE provided an effective system for tracking enrolment, completion, transition, and long-term outcomes of students, helping to improve the model overtime. For example, Sulemana Osman Saaka. Program Manager of SfL, shared:

Research results have helped to streamline operations and ensure better value for money in the program delivery. By providing information that allows the program to adjust and make improvements,lessons can be learnt and then changes made. Research has helped in understanding progress of implementation and determining the way forward and confirming some best practices already known to SfL.

Research was also key to shifting CBE from being solely implemented by CSOs to becoming a government policy and program. According to Charles Otoo, for example, evidence, including that conducted internally by the government and later an independent evaluation commissioned by DFID (Akyeampong et al. Citation2018) convinced government that children were learning and showed that even the most disadvantaged can achieve as well as, or better than, children in the formal system, once given the opportunity.

The strong researcher–donor partnership between Akyeampong and Dolan was a critical influencer of CBE research gaining interest from the Ministry of Education. This process required careful planning from the outset and an explicit, shared awareness of the importance of connecting CBE evidence to the wider policy picture and adapting its messages to maximise the possibility of uptake. Additionally, being explicit about the dynamics within government, including who is most influential was highlighted as essential for getting government to listen to the evidence. Donors are afforded audiences with key policy makers, a privilege that can and should be used to amplify and promote local voices. Akyeampong stated:

At the start of this recent research on CBE I worked very closely to discuss with DFID how this research should be positioned to get interest and ownership from Government. This meant thinking about how the CBE research could speak to the wider system improvements needed in Ghana … .It can be a powerful partnership – if we are speaking with one voice … .It is important to understand who has influence and why – then they can be the spokesperson for the evidence, and will be more articulate.

4. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to shed light on role of multi-sectorial relationships in facilitating the uptake of research that ultimately led to the Government of Ghana adopting CBE. Drawing upon Hinton, Bronwin, and Savage’s (Citation2019) Pillars of Policy Impact framework, this study reinforces the importance of between-group partnerships of donor, government, and researchers that secured government buy-in. This study further underscores the importance of both formal and informal relationships between actors, highlighting the need for structures and opportunities to allow these relationships to thrive .

A further priority of our study was to better understand the role that CSOs have played in evidence uptake and to explore their role in the web of stakeholder relationships. This angle of our research was influenced by the central role CSOs played in the creation and evolution of the CBE model (Casely-Hayford and Hartwell Citation2010). Confirming our assumption, CSOs were emphasised across data sources as being an invaluable player in CBE’s success, particularly in the production and promotion of evidence. Compared with well-established and reciprocal formal and informal relationships with donors and researchers, however, CSO’s relationship with government was under-valued and strongly dependent upon intermediaries. This paper argues for the integration of a new pillar in the model of policy impact that gives due significance to local evidence producers.

In summary, our analysis underscores the importance of partnerships in the use and uptake of research that helped bring about the Government of Ghana’s adoption and scale up of CBE. The findings also strengthen the case for the inclusion of CSO actors as essential in CBE’s past and future success, pointing to their potential to sustain the initiative in the absence of donor funding. As nations tackle the learning crisis, we need to better understand how such alternative pathways to schooling can help close the learning gap. The authors argue these findings place additional responsibility on donors and Northern academics to challenge the power imbalances that may prevent local actors taking a key role in evidence production and uptake.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who took part in this research and who have supported the Complementary Basic Education program in Ghana. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Carter

Emma Carter is a Senior Research Associate at the Research for Equitable Access and Learning Centre at the University of Cambridge, with interests in the impacts of disadvantage on cognitive and social-emotional development. Following completion of her PhD in 2017, her roles have involved developing research instruments for the Speed Schools project in Ethiopia and undertaking a comprehensive evaluation of Complementary Basic Education in Ghana. Currently, Emma is working for the Mastercard Foundation’s Leaders in Teaching initiative which supports secondary teachers and school leaders in delivering quality instruction in Rwanda.

Rachel Hinton

Rachel Hinton is Global Education Research Lead at FCDO, and a Fellow of Practice at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. Rachel led the creation of RISE, EdTech, THRIVE, DeliverEd and the What Works Hub. She serves on the Global Evidence Education Advisory Panel Secretariat. In 2014, she established Building Evidence in Education with the World Bank, USAID, and UN. Rachel worked in Ghana, Western Balkans, Nepal and UNICEF in New York. She lectured in Social Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh and Kenyatta University. She serves on the Board of STIR, and as an advisory member for Brookings Scaling Initiative.

Pauline Rose

Pauline Rose is Professor of International Education, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre and Co-Director of Cambridge Global Challenges at the University of Cambridge. Her research in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia focuses on educational policy and practice, including in relation to inequality, financing and governance, and the role of international aid. Professor Rose works closely with international aid donors and non-governmental organisations, providing evidence-based policy advice on a wide range of issues aimed at fulfilling commitments to equitable access to quality education for all.

Ricardo Sabates

Dr Ricardo Sabates is Professor in Education and International Development at the Faculty of Education. He is a trained economist, with PhD in Development Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is a member of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre. He is currently the Director of Research at the Faculty of Education. His area of research focuses on educational inequalities in access and learning, primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia. He has researched inequality patterns in educational access, second chance opportunities in education for marginalised children, and accountability for education.

Notes

1 These documents have also been marked with an * in the reference list below.

References

- *Akyeampong, K., E. Carter, S. Higgins, P. Rose, and R. Sabates. 2018. “Understanding Complementary Basic Education in Ghana: Investigation of the Experiences and Achievements of Children After Transitioning Into Public Schools.” In Report for DFID Ghana Office. Cambridge: REAL Centre, University of Cambridge. doi:10.5281/zenodo.2582955.

- Akyeampong, K., E. Carter, R. Rose, and J. Stern. 2022. “Language of Instruction and Achievement of Foundational Literacy Skills for Girls and Boys in Ghana.” In Girls’ Education and Language of Instruction: An Extended Policy Brief, edited by L.O. Milligan and L. Adamson, 37–43. Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath and the Girls’ Education Challenge, FCDO, UK.

- Bamberger, M. 2010. Reconstructing Baseline Data for Impact Evaluation and Results Measurement. PREM Notes; No. 4. World Bank.

- *Carter, E., P. Rose, R. Sabates, and K. Akyeampong. 2020b. “Trapped in low Performance? Tracking the Learning Trajectory of Disadvantaged Girls and Boys in the Complementary Basic Education Programme in Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Research 100: 101541. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101541.

- *Carter, E., R. Sabates, and P. Rose. 2018. “Assessing Economic, Educational and Aspirational Trajectories Five Years After Completing Complementary Basic Education in Ghana.” In Report for DFID Ghana Office. doi:10.5281/zenodo.2579095.

- Carter, E., R. Sabates, P. Rose, and K. Akyeampong. 2020a. “Sustaining Literacy from Mother Tongue Instruction in Complementary Education Into Official Language of Instruction in Government Schools in Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Development 76: 102195. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102195.

- Carvalho, S., A. Asgedom, and P. Rose. 2022. “Whose Voice Counts? Examining Government-Donor Negotiations in the Design of Ethiopia's Large-Scale Education Reforms for Equitable Learning.” Development Policy Review: Journal of the Overseas Development Institute 40 (5): e12634. doi:10.1111/dpr.12634.

- *Casely-Hayford, L., and A. Ghartey. 2007. “An Impact Assessment of School for Life (SfL): Final Report.” In Report Produced by the SfL Internal Impact Assessment Team. http://www.web.net/~afc/download2/Education/complimentary_edu_finalreport.pdf.

- Casely-Hayford, L., A. B. Ghartey, and J. Agyei-Quartey. 2021. “Complementary Basic Education: Parental and Learner Experiences and Choices in Ghana’s Northern Regions.” In Reforming Education and Challenging Inequalities in Southern Contexts, edited by P. Rose, M. Arnot, R. Jeffrey, and N. Singal, 185–205. London and New York: Routledge.

- *Casely-Hayford, L., A. Ghartey, J. Agyei-Quartey, and S. Otopah. 2017. “Learning from Complementary Basic Education Implementation in Ghana: An Exploration into the Effectiveness and Best practices across Different Contexts.” Draft report produced by the Complementary Basic Education Management Unit.

- Casely-Hayford, L., and A. Hartwell. 2010. “Reaching the Underserved with Complementary Education: Lessons from Ghana’s State and Non-State Sectors.” Development in Practice 20 (4–5): 527–539. doi:10.1080/09614521003763152.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. Abingdon: Oxon.

- Daly, K., E. Carter, and R. Sabates. 2022. “Silenced by an Unknown Language? Exploring Language Matching During Transitions from Complementary Education to Government Schools in Ghana.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, DOI: 10.1080/03057925.2021.1941772.

- DeStefano, J., A. M. S. Moore, D. Balwanz, and A. Hartwell. 2007. Reaching the Underserved: Complementary Models of Effective Schooling. Academy for Educational Development (AED). Accessed 23 September 2019, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505689.pdf

- DeStefano, J., and A. M. Schuh Moore. 2010. “The Roles of non-State Providers in ten Complementary Education Programmes.” Development in Practice 20 (4-5): 511–526. doi:10.1080/09614521003763061.

- DFID. 2018. “Complementary Basic Education (CBE) Programme Entering a New Phase in Ghana.” Accessed 23 September 2019 GOV.UK website. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/complementary-basic-education-cbe-programme-entering-a-new-phase-in-ghana.

- Georgalakis, J., and P. Rose. 2019. “Introduction: Identifying the Qualities of Research–Policy Partnerships in International Development – A New Analytical Framework.” IDS Bulletin 50: 1. doi:10.19088/1968-2019.103.

- *Hartwell, A. 2006. Meeting EFA: Ghana SfL (EQUIP2 Case Study). Washington, D.C.: Educational Quality Improvement Program 2 (EQUIP2), Academy for Educational Development (AED). Accessed 22 September 2019, from https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/e2-GhanaCaseStudy__1_.pdf.

- Hinton, R., R. Bronwin, and L. Savage. 2019. “Pathways to Impact: Insights from Research Partnerships in Uganda and India.” IDS Bulletin 50: 1. doi:10.19088/1968-2019.105.

- Hsieh, H. F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- *Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast. 2015. Assessing the Effectiveness and Capacity Building Needs of the National Service Personnel and National Service Secretariat for Their Integration to Scale-Up the Complementary Basic Education Programme. UNICEF.

- Menashy, F. 2016. “Understanding the Roles of non-State Actors in Global Governance: Evidence from the Global Partnership for Education.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (1): 98–118. DOI: 10.1080/02680939.2015.1093176.

- Mfum-Mensah, O. 2011. “Education Collaboration to Promote School Participation in Northern Ghana: A Case Study of a Complementary Education Program.” International Journal of Educational Development 31 (5): 459–465. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.05.006.

- *Ministry of Education. 2013. Complementary Basic Education Policy Framework. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Education.

- *MOESS. 2007. Complementary Basic Education Policy Document. Unpublished document, Accra: Ministry of Education, Science and Sport.

- Oliver, K., and P. Cairney. 2019. “The dos and Don’ts of Influencing Policy: A Systematic Review of Advice to Academics.” Palgrave Communications 5 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0232-y.

- Pritchett, L. 2018. “What We Learned from Our RISE Baseline Diagnostic Exercise”. Rise blog. https://riseprogramme.org/blog/baseline_diagnostic_exercise_1.

- Rose, P. 2009. “NGO Provision of Basic Education: Alternative or Complementary Service Delivery to Support Access to the Excluded?” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 39 (2): 219–233. DOI: 10.1080/03057920902750475.

- School for Life. 2017. “Partners and Networks.” Accessed https://www.schoolforlifegh.org/networks-affiliations.

- Shinohara, T. 2021. “Complementary Basic Education Programmes for Out-of-School Children in Bangladesh, Ghana and Ethiopia: A Comparative Overview.” In Education and Development, edited by J. Agebaire, A. Agema, and J. Kumari, 71–93. Makurdi: Sevhage Publishers.