ABSTRACT

Important agricultural technologies do not always reach smallholder farmers at the pace required to improve production. The Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture’s farmers’ hubs is designed to improve access to new technologies. We describe how these businesses fit into the innovation system of Bangladesh and document what products and services are being provided to the community. We surveyed 300 farmers who were participants or non-participants living near six study hubs. The most used service (97 per cent or participants) was seedlings grown in specialised soil less media, which is a product supported through their research mechanism and where there are few alternatives in the market. However, other services like farm machinery, and purchasing of produce were less well used by participants. The location of the farmers’ hubs in smaller communities can enhance these farmers’ access to certain information and technology.

Introduction

Across the Eastern Gangetic Plains (EGP), including Bangladesh, farm sizes are very small (average 0.6 ha) and plots are usually fragmented. It is one of the most densely populated places in the world, with approximately 300 million people living, working, and relying on agricultural production. The farming systems are dominated by rice production with wheat, maize, pulses, and minor crops included in the rotation. The small plot-size has restricted the utility of four-wheeled tractors, however mechanisation of tillage using two-wheel tractors has spread across Bangladesh since the 1990s (Miah, Haque, and Bell Citation2019). Growth in agricultural productivity over the last 20 years has been modest (0.03 per cent) in many regions of Bangladesh, and there have been declining levels of technical efficiency (Alam et al. Citation2011 Bagchi, Rahman, and Shunbo Citation2019;). While researchers have been investigating options to increase productivity and have identified several profitable cropping options to intensify production (e.g. Gathala et al. Citation2021), the scale at which new practices must be adopted for meaningful impact creates new challenges. Empirical studies on scaling in this region has focused on the adoption and dis-adoption processes related to Conservation Agriculture Sustainable Intensification (CASI) for cereal and rice production (Brown et al. Citation2022 Brown, Paudel, and Krupnik Citation2021;). This research has shown that both public and private organisations support transfer to farmers of agricultural technology, and multiple organisations are often needed for adoption and in some cases scaling-out of technologies.

To increase agricultural productivity and ultimately improve food security in Bangladesh, the question of how to accelerate access and adoption of technology to large numbers of small-scale farmers must be addressed. There have been significant changes to the public sector extension system (Chowdhury, Odame, and Sarapura Citation2019) in Bangladesh towards solving specific problems, supporting group-based learning opportunities, and rapid adoption of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) (Kamruzzaman et al. Citation2019; Medendorp et al. Citation2022). There is a diversity of organisations involved in the Research and Development (R&D) system, with Rahman et al. (Citation2017) identifying 50 agricultural and training organisations operating in Bangladesh. More recently the disruptions to agricultural input supply and agricultural service supply (including labour and machinery services) because of the COVID-19 pandemic have demonstrated the vulnerability of the food production system in Bangladesh (Amjath-Babu et al. Citation2020; Mottaleb, Mainuddin, and Sonobe Citation2020). This disruption has highlighted the lack of knowledge we have about how small and distributed private businesses function in agri-food chains. Specifically in Bangladesh how they can be used more in the future to deliver important services and products to enable change of practice by smallholder farmers.

In this study, we focus on one initiative designed to help deliver services to smallholder farmers in Bangladesh. Farmers’ Hubs were developed by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) and are designed to provide multiple services to smallholder farming communities. SFSA (created in 2001, SFSA Citation2021) is an independent non-profit organisation established by the agribusiness Syngenta, which has its own strategy to improve the livelihoods of smallholders in developing countries. In this context, SFSA is acting as a facilitator to catalyse collective action and enhance farmers’ access to information and technology (Hellin and Camacho Citation2017). The hubs are owned and operated locally by entrepreneurs, agribusiness suppliers, or farmers’ cooperatives. Each hub is run as a commercial business, but they are operated as a network of businesses in a franchise system and have links to research and extension services. Initial support from SFSA is provided in the form of training the hub owner, access to professional networks, and business development opportunities. However, they are designed to be financially independent of SFSA and to become a commercial service and input provider that is valued by local communities. We see the farmers’ hubs as one model ( shows the diversity of different approaches) to encourage the successful adoption at scale of agricultural technologies in Bangladesh, and it should be noted that small rural traders in Bangladesh often serve a dual role of also providing extension information (Mottaleb, Rahut, and Erenstein Citation2019). Our study documents how farmers’ hubs are being used to improve the adoption at scale of new agricultural technologies and identify opportunities for them to be used more effectively. Our objective was to first describe how these businesses fit into the innovation system of Bangladesh and, second, document what products and services are being provided by the hubs to the local community. Then, we discuss how and why the hubs have successfully delivered some services but others may be less well used in the local community.

Table 1. Different types of scaling mechanisms to provide access to new agricultural technology (this includes information and services).

Literature review

Important agricultural technologies (e.g. new crop varieties, machinery practices, input management practices) do not always reach their intended beneficiaries. The processes, tools and support networks needed to see the adoption of new technology at the household level may be different from those required to deliver and encourage adoption of new technology to many smallholder farmers (Woltering et al. Citation2019). Scaling-out is focused on replication and expansion of technologies to new regions or farmers. In retrospect, scaling-out can be observed as a practice that was once only adopted by a few farmers, now being adopted, and used by many. Effective methods for scaling-out agricultural technology require a well-connected innovation system that links researchers, extension staff, private agri-businesses, service providers, input suppliers, farmer organisations and collectives, and individual farmers. The most effective way to operationalise these systems in different country contexts are an area of ongoing research (Hellin and Camacho Citation2017; Tarekegne Citation2022). The methods used for scaling a new pest management practice may be different from those needed for scaling new irrigation practices, and pilot projects rarely provide the information needed to assess the performance of interventions at scale (Woltering et al. Citation2019). Research providers are increasingly trying to partner with diverse organisations in the innovation system to help encourage the adoption of new practices based on the knowledge and technology they develop. At the same time, the inclusiveness of different approaches needs to be understood to ensure equitable access to agricultural technology and benefits that are shared across farming communities (Quisumbing and Kumar Citation2011).

In the EGP there is a predominance of small and localised private businesses that provide agricultural inputs, machinery services, and sometimes aggregate and market produce. Finding ways to foster linkages between research providers, extension officers, these types of private businesses and farmers to enable access to improved agricultural technologies is an ongoing challenge, however, the scientific literature on how to do this is scant. In some cases, third-party actors (e.g. development organisations) have linked farmers with markets for specific products, but the long-term viability of these relationships has not been assessed (Zamil and Cadilhon Citation2009). Innovation platforms (IPs) (Sartas et al. Citation2018; Totin, van Mierlo, and Klerkx Citation2020) are one way to bring all the stakeholders together to coordinate action to address a complex problem () and they are one tool used to operationalise networks in an innovation system. In Bangladesh the development of IPs has led to the establishment of new business models that provide equipment hire to facilitate the adoption of conservation agriculture practices (Brown, Paudel, and Krupnik Citation2021). Beyond IPs, there is a diversity of other mechanisms for scaling and tools by which the private and public components of the agricultural innovation system could potentially interact (summarised in ). In this study we focus on the farmers’ hubs as a method to encourage the adoption at scale of agricultural technologies in Bangladesh and document how they operate in the innovation system. The hubs are diverse and can include several of the organisational types listed in , however, they are designed as sustainable commercial enterprises. They provide some unique services, but similar private businesses can also supply comparable products. This creates an opportunity to understand why certain services are used by farmers who are hub participants versus those who are not participants.

Methodology

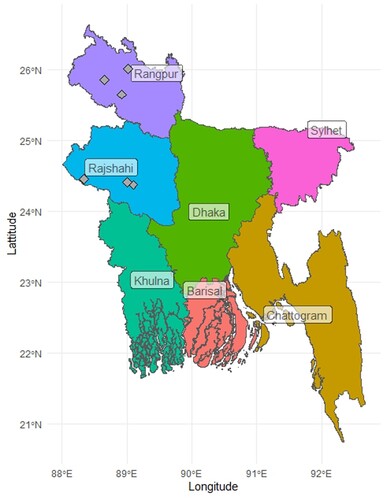

There is a total of 286 hubs listed as operating in Bangladesh (as of March 2021) so we developed a process to select the hubs that would be the focus of this project. A list of all the Hubs in Bangladesh was provided by SFSA, which contained location details, network assignment, and the time since establishment. We excluded hubs established in 2020 (80 in total) as these have not had enough time to develop fully. There were 40 hubs in the 2013–2017 establishment year group and 166 hubs in the 2018–2019 establishment year group. The financial performance of the hubs was not considered in the selection process. Only one of the hubs is listed as being owned by a woman; however, many hubs are family-owned and have women involved in decision-making in some way. The remaining hubs belonged to four networks that sit in two divisions. We randomly selected two hubs from the Rangpur division and three hubs from the Rajshahi division. Within this list were hubs that were run by small ethnic community groups in Bangladesh, and we deliberately included one of these in our study. These ethnic groups interact regularly with Bengali people in their region as part of their business practices. This ethnic hub falls under the Rangpur division. This gave a total of six hubs that formed the focus of our survey work ().

Figure 1. Map showing the towns nearest the study Hubs in Bangladesh chosen for inclusion in this study (grey diamonds). The background map was sourced from Ashiq Citation2020.

After selecting the hubs, a list of the participant farmers was collected from the SFSA staff in each region. The target population of this study are those farm households who engaged with the selected hubs in some manner. A participant may use the hubs for some services or provide some information, but not all agronomic services are needed. Participants of the hubs do not exclusively interact with hub owners but do access the hubs for certain services. In contrast, non-participant farmers are those who live in nearby villages of the selected hubs but did not receive any support, information, or services from the hubs. They may be aware of the hubs but choose to access services and advice from elsewhere in the community. A list of non-participant farmers was collected from the respective Sub-assistant Agricultural Officer (SAAO) who are field-level public extension agents in the study villages. From each selected hub, around 50 farmers were interviewed randomly from the lists provided. In addition, three to five more samples were collected from each location to keep the total sample size at least 300. The interview schedule included questions related to socio-demographic, agricultural inputs and farm machinery services, extension advisory services, farm productivity, and level of satisfaction with existing services. The prepared interview schedule was then pre-tested in the field before final data collection.

The enumerators collected data through face-to-face interviews under the supervision of the research team between April and June 2021. Data were collected using a digital tablet and uploaded to a server. In case of inaccuracy, inconsistency, and incompleteness identified of any data, communication (through mobile phone) was made with the respondent to resolve the problem. Data were analysed by using SPSS and SATA software. Simple descriptive statistics were used to estimate perception about the product and services received by the sample respondents and presented as averages, percentages, ratio, frequency, etc. after generating descriptive tables.

A total of 323 samples were collected across hubs (, Appendix 1). Among the respondent’s 52 per cent are participants and 48 per cent non-participants and 49 per cent were in Rangpur division and 51 per cent in Rajshahi division. The age structure of the sample respondents was classified into three age groups such as less than 35, 35–45, and more than 45 years. Interestingly, each group comprised about one-third of the total. However, a relatively higher percentage of young respondents belong to participant households (Appendix 1). The involvement of women farmers in our quantitative survey was very low (no females in the non-participant group and only 4 per cent of participant respondents). The few women participants we interviewed were part of the ethnic minority hub in the Rangpur division. This does not mean women farmers are not involved in agricultural operations and decisions in the household, but rather the people we spoke to during the survey were the members of the household responsible for the tasks associated with the buying of inputs and services (and selling of outputs). These tasks are predominately the responsibility of men household members in this context (also seen in Jost et al. Citation2016).

Table 2. Distribution of the samples across division and participant category in our quantitative survey. Figures in parentheses indicate the percentage. We have removed the Hub names and given them a code name to de-identify the respondents.

Most of the respondents had below primary level of education (<10 years of education), 35 per cent respondents had six to ten years of education, followed by 31 per cent with one to five years (Appendix 1). Crop production was listed as the primary business of 95 per cent of the respondents, with a commercial business listed as their secondary occupation (22 per cent). Other common secondary occupations included livestock and poultry production (18 per cent) and general labourer jobs that were paid on a daily wage (16 per cent) (Appendix 1).

Besides the quantitative survey, participants observation, key informant interview, and expert consultation were performed to capture the diverse perspectives on farm input services and delivery mechanisms. The research team visited the study sites as a scoping trip prior to the quantitative survey design. We visited several hubs and met with hub owners, extension personnel, network manager, and SFSA local staff. All discussions were recorded (audio) then transcribed accordingly. The research team organised two expert consultation meetings: (i) one with the extension personnel and researcher; and (ii) another with the SFSA personnel both local and national level to gather more information.

Results

Where do the farmers’ hubs sit in the innovation system?

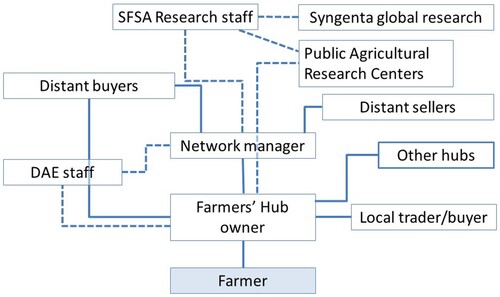

Through our learning and experience during the scoping trip, participant observation, and expert interviews, we documented how the farmers’ hubs connect farmers with research, extension, and market agents (). The hubs are positioned in locations that may lack a competitive market for some inputs or services and are generally closer to farming communities (than in large town centres). The six focal hubs included in our study were focused on small vegetable production. During the scoping trip, we learned that the farmers’ hubs buy coco-peat media, plastic trays, and farm machinery from the network managers. They buy seeds from different sources, based on the recommendation of the SFSA R&D (Research and Development Centre), passed on through the network managers. They sell vegetable seedlings to farmers as well as provide advice and support to farmers on a diversity of production issues.

Figure 2. Illustration of how the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) farmers’ hubs connect farmers with research, extension, and market agents in Bangladesh. Flows of information and advice are represented by the dashed lines and flows or access to services and information are represented by the solid lines.

The farmers’ hubs act as intermediaries between farmers and agricultural researchers (). One of the crucial instruments of this link is the SFSA R&D, in Rangpur district. During the scoping trip, it was observed that two full time scientists are employed to conduct field trials of different alternative technologies. However, the SFSA R&D centre does not have the capacity or mandate to develop new varieties technologies, since they do not have the laboratories to conduct such research activities. Their role is to localise and optimise the existing technologies and crop varieties through trials for the benefit of the hub participants. The varieties tested here are from different seed companies and are commonly available in the market. Other technologies like farm machineries and cultivation techniques are also tested in this facility. The SFSA personnel, during both the scoping trip and the expert interview, claimed that they always provide unbiased suggestions based on the trial results, and no preference is given to seeds from the Syngenta Company. Guidelines about the use of different farm machinery and cultivation techniques are passed on through the channel of farmers’ hubs. Thus, it has been observed that the SFSA Farmers’ Hubs are a mechanism where the use of suitable agricultural technologies can be scaled out through the network of hubs.

Through our expert interviews, we discovered more about the current relationship between DAE, other researchers, and the hubs. It was reported that DAE has strong relationships with other stakeholders of the agricultural production and marketing system like farmers, NGOs and private companies (also see Kamruzzaman et al. Citation2019). However, there is currently no formal relationship between the hub and the Regional Agricultural Research Station (RARS) of Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, but there is a link between RARS and the SFSA R&D department. If SFSA R&D staff come to RARS with farmers, then RARS staff will show them their agricultural technology and have discussions. Sometimes RARS staff may collect/observe technology from SFSA R&D. DAE officials sometimes join in large-group training activities run by SFSA and DAE has a direct connection with a small number of hubs.

What products and services are delivered by the hubs?

The SFSA Farmers’ Hubs provide different services like selling seedlings, renting small machinery, buying farm output, providing information regarding agricultural practices, providing crop insurance schemes, etc. The most common service provided by the six study hubs in our survey was the selling of seedlings, with 97 per cent of the hub participants using this service in some way and there was a statistically significant difference in the degree of use by hub participants versus non-participants (). This involved the development and use of the coco-peat soil media in seedling trays and the use of crop types and varieties that had been trailed by the SFSA research team and were optimised for local conditions. This seedling technology and practice information provides farmers with a much earlier harvest for some crops and can lead to a price advantage at the time of sale. Overall respondents were very satisfied (58 per cent) or satisfied (41 per cent) with this service and the results they achieved. However, not all farmers purchase seedlings through the hub alone as the price of these is high relative to other sources or the use of farmer-saved seeds. Hub participants also sourced seeds and seedlings from retailers in the local market (32 per cent, compared to 51 per cent of non-participants, significant difference), and produced them independently (18 per cent, compared to 34 per cent of non-participants, significant difference) (). Retailers in distant markets also provided a small number of seeds or seedling inputs (6 per cent for non-participants, 3 per cent for participants). However, the coco-peat medium-based seedlings were not commonly available in the market, so the farmers’ hubs were the only source in their respective areas if farmers wanted such seedlings.

Table 3. Information from respondents to our quantitative survey about the source of seeds or seedlings they use and the farm machinery they use.

It was reported that the cost of seedlings is comparatively higher than farmers producing seedlings from their saved seeds (as the seedlings in the hubs are produced under a controlled environment), but the quality of hub seedlings is better. When we asked survey respondents how their productivity and farm income had changed over time (from 2018 until 2021) most people identified that it had increased. We found that a greater proportion of hub participants said their productivity had greatly increased, whereas a greater proportion of non-participants said their productivity had moderately increased (). For hub participants this change was attributed to a shift from the use of seeds to the use of good-quality seedlings ().

Table 4. Information from respondents to our quantitative survey about the direction of change in productivity and the reasons behind the change in productivity they observed between December 2018 and 2021.

There were several machinery services provided by the six study hubs () but they had a moderate level of use by farmers. These include access to two-wheel tractors, combine harvesters and seedling transplanters (rented out to the farmers or service providers). Of the hub participants 12 per cent accessed some machinery services from the hub, and this was most commonly power sprayers (48 per cent), mechanical weeders (17 per cent) and seedling transplanters (10 per cent). Respondents also used machinery services provided by local retailers (41 per cent of non-participants, 31 per cent of participants, significant difference), and owned some machinery themselves (37 per cent of non-participants, 42 per cent of participants, significant difference). A relatively high number of respondents sourced machinery services from other farmers (22 per cent of non-participants, 15 per cent of participants) ().

Hub owners and network managers act as aggregators of produce from many farmers, and this does enables access to distant markets at a good price (i.e. the price may be less through the services of a middleman). Buying and selling were reported by SFSA as one of the major sources of income by the hubs across Bangladesh. However, it was observed during the scoping trips and the survey that all hubs do not engage in this practice equally. For the six study hubs in our survey, 51 per cent of hub participants reported knowing about this service and 42 per cent said they used this service to gain access to better forward linkages. Of those who did use this service (70 respondents), they were either satisfied (77 per cent) or very satisfied (23 per cent) with this offering. Hubs. The hubs provide support for a range of post-harvest handling services for vegetables such as potato, tomato, chill, brinjal etc. This includes the use of plastic crates (borrowed from the hubs unless sent to distant markets) (26 per cent of participants), the use of vans to transport the produce (11 per cent of participants) and access to weighing machines (10 per cent of participants) ().

Table 5. Information from respondents to our quantitative survey about what they knew about the range of post-harvest handling services the Farmers’ Hub is offering, and which of them they were currently using. Shown as a percentage of respondents who participate in the Hubs.

To understand the impact of buying and selling services of hubs on the local community, we asked the respondents about where their vegetable produce is consumed or sold. As mentioned earlier, not all hubs participate in this function equally and in our survey only one of the sample hubs (hub A) did it at a significant scale, where about 28 per cent of the produce was sold to the hubs by the participant farmers. In case of that hub, most of the output is sold at local markets either directly or via middlemen (57 per cent of produce for non-participants, 32 per cent of produce for participants), and some goes to distant markets via a middleman (11 per cent of produce for non-participants, 19 per cent of produce for participants). Some is consumed or used in the household and was similar across the participants and non-participants of the hub (16–17 per cent of produce), (). Selling through the hub offers potential advantages through reduced transportation cost, lower perishability, and handling. Marketing costs and post-harvesting costs are lower, and crops are accurately weighted at the hub, therefore profit margins should be higher for the same sale price. It was observed during the scoping trips and through the survey question about market linkages that in some hubs the hub owners and network managers act as a connector to distant markets through the relationships they have with others, but our survey did not explicitly show the quantities sold through this process.

Table 6. Information from respondents to our quantitative survey about what proportion of their produce they consume at home or sell to customers.

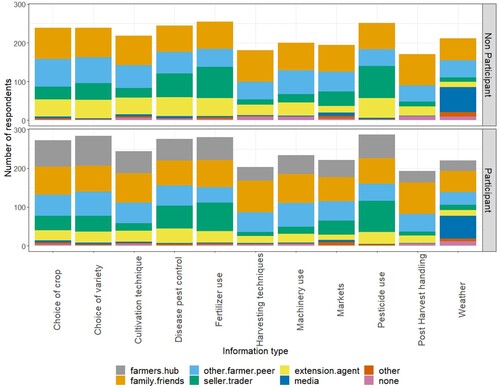

In addition to the access to services related to farm production, access to information about farm practices, techniques, pest issues and weather are also important for improving productivity (collectively called agri-advisory services). We know that smallholder farmers use a diversity of information sources in their daily lives but wanted to know specifically which types of information came from each source. For those participants in the hubs ( bottom graph) some information across all information types was provided by the hub, but the choice of which variety to use (77 per cent), the crop type choice (68 per cent), pesticide use advice (61 per cent) and fertiliser use advice (59 per cent) were the most identified by hub participants. In the non-participant group ( top graph) sellers and traders provided information about pesticides (83 per cent) and fertiliser use (80 per cent) to more of our survey respondents. The extension agents also provided relatively more information to non-participants in several key areas (pesticide use: 51 per cent; disease and pest control: 50 per cent; choice of crop variety: 48 per cent). For all respondents family and friends and other farmers and peers were used for a diversity of information types. Weather was perhaps the only information type where media content (newspapers, televisions, YouTube channels, and social media, radio) played a large role.

Discussion

Where do the farmers’ hubs sit in the innovation system?

Our study has shown that the Farmers’ Hub role is more than that of a commercial input supplier, because of the additional layers of testing and advice they provide to farmers. The hubs have already developed mechanisms through which farmers are connected to agricultural researchers at the R&D, public research stations within Bangladesh, and researchers from other countries through the SFSA global research platform. Some opportunities may be created by greater integration of the hubs with DAE and other local research organisations, to encourage the flow of practice change information through this network to farmers.

The traditional view of innovation in agricultural systems involves linear information dissemination, usually from a research provider, through a publicly funded extension system to support the adoption of new practices by farmers. However, this approach under-estimates the farmers’ role as innovators (Bellotti and Rochecouste Citation2014) and ignores the powerful influence of private sector stakeholders in providing services, tools, and information to farmers. As shown in there are many organisations involved in supporting farmers to trial and adopt new agricultural practices. Our study demonstrates that there are many pathways by which farmers receive information and services in agriculture including through agribusinesses (as seen by Mottaleb, Rahut, and Erenstein Citation2019). Hellin and Camacho (Citation2017) suggest that when the objective is multi-faceted, other actors besides research organisations may be better placed to act as network brokers. The hub model which connects farmers through to research outcomes and knowledge from both the public and private system is an example of this in action. But like other agribusinesses there are technologies and services they provide to many farmers, and certain technology and services they provide to a few farmers. In combination with other private businesses, public extension, innovation platforms (Totin, van Mierlo, and Klerkx Citation2020) and farmer peer-to-peer learning opportunities the hubs are enabling access to tools and knowledge to a greater number of farmers in rural communities.

What products and services are delivered by the hubs?

The most used service (97 per cent or participants) was seedlings grown in specialised media with farmers supported through the delivery of research knowledge to optimise production. The shift to seedlings does incur greater production costs and so carries some risks, however farmers can receive higher prices for their vegetables because they could sell them earlier. Given the relatively young age of farmers who are participants of the hub support to manage this risk is important. This demonstrates one of the harder-to-measure aspects of participation in hubs (or other collective groups), which is the de-risking of practice change through support and knowledge. A similar process of service providers creating an enabling environment for experimentation in East Africa was described by Pircher et al. (Citation2022). For the practices that were straightforward to measure we can say there are some products and services for which the hubs deliver a highly valued product (e.g. seedlings grown in specialised media), those for which the hubs provide a useful product along with other providers in the market (e.g. certain types of agricultural information, ), and those for which the hubs provide a service to a minority of farmers (e.g. access to markets and sell produce).

This was a short and limited study that only focused on six sample hubs in two regions. Therefore, the conclusions we draw may not be appropriate for all the hubs across Bangladesh. A future study involving a larger sample of hubs may provide additional insights, especially in relation to services not commonly provided at the six sample hubs and services that are directly relevant to women farmers. Given we had few women respondents in our quantitative survey (both hub participants and non-participants) we are limited in the conclusions we can draw regarding gender. However, during the scoping trips, it was observed that women’s labour was involved in seedling preparation and other activities. In the hubs 80–90 per cent of the processing tasks related to seedling production are done by women labourers. Thus, the hubs create employment opportunities for women agricultural workers (but we have no comparison with other similar businesses). The contribution of women to some aspects of farming operations is high in Bangladesh and could be supported further (Jost et al. Citation2016; Rahman et al. Citation2017; Rana, Kiminami, and Furuzawa Citation2022; Medendorp et al. Citation2022; Theis et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, some of the services delivered by the hub are generally the responsibility of men farmers in the household, and therefore they visit the hubs more frequently.

To improve the effectiveness and utility of the hubs we recommend first, that hubs have a greater emphasis on de-risking the adoption process for farmers across a diversity of services they provide. Second, research on government initiatives to encourage the adoption of farm machinery has identified areas of likely benefit for both men and women farmers (Theis et al. Citation2019). The operationalisation of such schemes needs partners like the hubs to ensure farmers can access the technology and knowledge at the same time. Third, people we spoke to identified a need for the private sector (beyond just the hubs) to become more involved in developing post-harvest processing facilities in partnership with farmers. They noted that farmers currently do not receive a fair price when bulk-handled commodity crops are produced at a large scale. As a first step towards this longer-term goal the hubs could focus on further promoting the aggregation of production and purchase of the crops by the hubs to be sold. There is a need to examine the costs and benefits of this approach to different stakeholders at a pilot scale as it may be risky for some hub owners.

Conclusions

Our survey and observations show that the SFSA Farmers’ Hubs are successful in providing a service (coco-peat based seedlings), which is supported through their own research mechanism and where there are no same alternatives in the market. However, in case of other services like farm machinery, post-harvest tools, and purchasing of farm produce, where there is no unique contribution of the hubs, and there are alternatives in the market, the SFSA farmers’ hubs have not been successful in the same degree. The hubs do make a valuable contribution to the diversity of organisations needed to facilitate the adoption at the scale of agricultural technologies in Bangladesh as part of the innovation system.

The farmers’ hubs and equivalent initiatives are important for making sure that new agricultural technologies reach their intended beneficiaries. While the differences we observed between participants and non-participants of the farmers’ hubs were subtle, there was some evidence that the hubs are supporting younger farmers to trial, adopt, and see the benefits of more challenging farming practices. There are flow-on benefits to farming communities through greater capacity and confidence of farmers that is hard to value. The trialling and optimising of practices in the local context before are a critical step in the adoption process that if missed, can lead to dis-adoption of practices.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank both the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR; project CROP/2020/202) and Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA). The enumerators involved in this project did a tremendous job under very difficult circumstances. Our thanks go to Sambhu Singha, Md. Burhan Uddin, Md. Asaduzzaman Papon, Abu Ahamed Sabbir, Md. Shahadut Hossain, Marjia Islam, Farjana Nazrin, and Jannatul Maoa Mim. We would like to thank the Farmers’ Hub owners, Network Managers, and farmers who participated in this study. We appreciate the support received from Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU) particularly the Bureau of Socioeconomic Research and Training (BSERT) and from the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) personnel. Helpful guidance was provided by Tamara Jackson, Kuhu Chatterjee and Brendan Brown (the SDIP team).

This project proposal was reviewed by the CSIRO Social and Interdisciplinary Science Human Research Ethics Committee Executive and the international development expert disciplinary CSSHREC member on February 16, 2021. Application number 174/20.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

M. Nahid Sattar

M. Nahid Sattar is an Applied Economist, currently a Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Bangladesh Agricultural University. His research includes economic analysis of production systems and markets, sustainable use of natural resources, food and nutrition security of households, and agricultural policy.

Sarina Macfadyen

Dr Sarina Macfadyen supports the Bangladesh team via her role in CSIRO Australia as a scientific leader in farming systems analysis.

Md. Wakilur Rahman

Mr. Wakilurb Rahman brings years of experience collaborating with development partners. His expertise spans gender issues, livelihoods, climate change, impact assessment, and food and nutritional security, with a strong emphasis on community development.

Fahana Tahi Tiza

Ms. Fahana Tahi Tiza is part of the Department of Rural Sociology, Bangladesh Agricultural University. She conducts research on socio-demographic issues with an emphasis on remittance, international migration, child education and women's empowerment.

References

- Alam, M.J., G.V. Huylenbroeck, J. Buysse, I.A. Begum, and S. Rahman. 2011. “Technical Efficiency Changes at the Farm-Level: A Panel Data Analysis of Rice Farms in Bangladesh.” African Journal of Business Management 5 (14): 5559–5566.

- Amjath-Babu, T.S., T.J. Krupnik, S.H. Thilsted, and A.J. McDonald. 2020. “Key Indicators for Monitoring Food System Disruptions Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from Bangladesh Towards Effective Response.” Food Security 12 (4): 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2.

- Ashiq, A.R. 2020. “Making the Map of Bangladesh using R.” RPubs by RStudio, University of Dhaka. https://rpubs.com/asrafur_ashiq/map_of_bangladesh.

- Bagchi, M., S. Rahman, and Y. Shunbo. 2019. “Growth in Agricultural Productivity and Its Components in Bangladeshi Regions (1987–2009): An Application of Bootstrapped Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA).” Economies 7 (2): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020037.

- Bellotti, B., and J.F. Rochecouste. 2014. “The Development of Conservation Agriculture in Australia—Farmers as Innovators.” International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2 (1): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30011-3.

- BIID. 2021. Bangladesh Institute of ICT Development, projects, https://www.biid.org.bd/#projects.

- Brown, P.R., M. Anwar, Md.S. Hossain, R. Islam, Md.Nur-E.-Alam Siddquie, Md.Mamunur Rashid, Ram Datt, et al. 2022. “Application of Innovation Platforms to Catalyse Adoption of Conservation Agriculture Practices in South Asia.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 20 (4): 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1945853.

- Brown, B., G.P. Paudel, and T.J. Krupnik. 2021. “Visualising Adoption Processes Through a Stepwise Framework: A Case Study of Mechanisation on the Nepal Terai.” Agricultural Systems 192: 103200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103200.

- Chowdhury, A., H.H. Odame, and S. Sarapura. 2019. “How do Extension Agents of DAE use Social Media for Strengthening Agricultural Innovation in Bangladesh?” Rural Extension & Innovation Systems Journal 15 (1): 10–19.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2014. Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: A Mapping and Capacity Assessment.

- Gathala, M.K., A.M. Laing, T.P. Tiwari, Jagadish Timsina, Fay Rola-Rubzen, Saiful Islam, Sofina Maharjan, et al. 2021. “Improving Small-Holder Farmers’ Gross Margins and Labor-use Efficiency Across a Range of Cropping Systems in the Eastern Gangetic Plains.” World Development 138: 105266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105266.

- Hellin, J., and C. Camacho. 2017. “Agricultural Research Organisations’ Role in the Emergence of Agricultural Innovation Systems.” Development in Practice 27 (1): 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2017.1256373.

- Jost, C., F. Kyazze, J. Naab, Sharmind Neelormi, James Kinyangi, Robert Zougmore, Pramod Aggarwal, et al. 2016. “Understanding Gender Dimensions of Agriculture and Climate Change in Smallholder Farming Communities.” Climate and Development 8 (2): 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1050978.

- Kamruzzaman, M., A. Chowdhury, H.H. Odame, S. Sarapura, and M. Kamruzzaman. 2019. “How do Extension Agents of DAE use Social Media for Strengthening Agricultural Innovation in Bangladesh?” Rural Extension & Innovation Systems Journal 15: 10–19.

- Medendorp, JohnWilliam, N. Peter Reeves, Victor Giancarlo Sal Y. Rosas Celi, Md Harun-Ar-Rashid, Timothy J. Krupnik, and Anne N. Lutomia. 2022. “Large-scale Rollout of Extension Training in Bangladesh: Challenges and Opportunities for Gender-Inclusive Participation.” PLoS One 17: e0270662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270662.

- Miah, M.M., M.E. Haque, and R.W. Bell. 2019. “Impact of Multi-Crop Planter Business on Service Providers’ Livelihood Improvement in Some Selected Areas of Bangladesh.” Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research 44 (3): 409–426. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjar.v44i3.43475.

- Mottaleb, K.A., M. Mainuddin, and T. Sonobe. 2020. “COVID-19 Induced Economic Loss and Ensuring Food Security for Vulnerable Groups: Policy Implications from Bangladesh.” PLoS One 15: e0240709. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240709.

- Mottaleb, K.A., D.B. Rahut, and O. Erenstein. 2019. “Small Businesses, Potentially Large Impacts.” Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies 9 (2): 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-08-2017-0078.

- NAEP. 2015. National Agricultural Extension Policy, Ministry of Agriculture, The People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- NAMP. 2010. National Agricultural Mechanization Policy 2020, Ministry of Agriculture, The People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Pircher, T., M. Nertinger, L. Goss, et al. 2022. “Farmer-centered and Structural Perspectives on Innovation and Scaling: A Study on Sustainable Agriculture and Nutrition in East Africa.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 0: 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2022.2156894.

- Quisumbing, A.R., and N. Kumar. 2011. “Does Social Capital Build Women’s Assets? The Long-Term Impacts of Group-Based and Individual Dissemination of Agricultural Technology in Bangladesh.” Journal of Development Effectiveness 3 (2): 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2011.570450.

- Rahman, M. W., M. S. Islam, L. Hassan, N. Z. Tanny, L. Parvin, and A. Bohn. 2017. Bangladesh: Extension, Gender and Nutrition Landscape Analysis. SSRN Electron. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3022470.

- Rana, S., L. Kiminami, and S. Furuzawa. 2022. “Role of Entrepreneurship in Regional Development in the Haor Region of Bangladesh: A Trajectory Equifinality Model Analysis of Local Entrepreneurs.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 6 (3): 931–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00241-y.

- Sartas, M., M. Schut, F. Hermans, P. Asten, and C. Leeuwis. 2018. “Effects of Multi-Stakeholder Platforms on Multi-Stakeholder Innovation Networks: Implications for Research for Development Interventions Targeting Innovations at Scale.” PLoS One 13: e0197993. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197993.

- SFSA (Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture). 2021. “Farmers’ Hub Webpage”. https://www.syngentafoundation.org/agriservices/whatwedo/farmersHub.

- Tarekegne, C. 2022. “Innovative Agriculture in Ethiopia: Public Insights on Its Arrangements.” Development in Practice 32 (3): 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2021.1937550.

- Theis, Sophie, Timothy J. Krupnik, Nasrin Sultana, Syed-Ur Rahman, Gregory Seymour, and Naveen Abedin. 2019. “Gender and Agricultural Mechanization: A Mixed-Methods Exploration of the Impacts of Multi-Crop Reaper-Harvester Service Provision in Bangladesh. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1837. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133260.

- Totin, E., B. van Mierlo, and L. Klerkx. 2020. “Scaling Practices Within Agricultural Innovation Platforms: Between Pushing and Pulling.” Agricultural Systems 179: 102764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102764.

- Woltering, L., K. Fehlenberg, B. Gerard, J. Ubels, and L. Cooley. 2019. “Scaling – from “Reaching Many” to Sustainable Systems Change at Scale: A Critical Shift in Mindset.” Agricultural Systems 176: 102652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102652.

- Zamil, Md. Farhad, and Jean-Joseph Cadilhon. 2009. “Developing Small Production and Marketing Enterprises: Mushroom Contract Farming in Bangladesh.” Development in Practice 19 (7): 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903055768.