ABSTRACT

In education theories, threshold concepts are key concepts within a discipline, and students must learn and understand them. Once they have comprehended those threshold concepts, it is argued that students' critical analysis and comprehension will be transformed and enhanced.

Intersectionality and participation are among the key threshold concepts in Gender and Development (GAD) theories and practices. However, within the classroom settings, students can find it challenging to understand the two concepts, and how to apply them in the development context from an equitable and inclusive approach.

This practice note shares my experience of designing assessments and activities using the threshold concept approach, where students learn about intersectionality and participation through a high-stake roleplay over three weeks, during which I observe the students' interactions with each other, as well as how they apply intersectionality and participation theories in their strategies and negotiations. Based on students' learning experiences over three years, I argue that the use of roleplay is highly effective and creates a safe space for students to navigate troublesome knowledge and embrace GAD threshold concepts through trial and error.

Sustainable Development Goals:

Introduction

Intersectionality and participation are among the key concepts in gender and development (GAD) which are easier to learn as intellectual concepts but harder to engage with at both practical and emotional levels. This is because Western university systems continue to view the student as an objective, disimpassioned learner. Instead, I argue that students need to embrace ideas and theories in their entirety so that one becomes sensitised to how ideas and theories work at the intellectual level, but also to their “real life” impacts upon people and communities, especially those who are marginalised and disempowered.

As a feminist who has done the usual sector jumps from a practitioner to an academic, I have been particularly interested in how students in my gender and development classes learn, apply, and reflect on GAD theories and methods. As I teach both undergraduate and postgraduate students, I have the benefit of learning with, and interacting among, a very diverse cohort of students, most of whom (especially the undergraduates) do not yet have working experience in the development sector and are studying a degree in development as part of their career pathway. What I have found is that while most curriculums and academics are sympathetic to a critical analysis of development studies, including efforts to decolonise, these ideas often remain at the intellectual, textbook level. How students become aware of inequalities and how power functions at the interpersonal level, as well as the emotions and affect that this learning can facilitate, are much less frequently discussed or explored. This practice note documents my work-in-progress of integrating threshold concepts of GAD as a way to engage and inspire students, the benefits of roleplay activities to encourage self-reflexivity, and the impact it has upon me as a feminist educator.

Threshold concepts

Development studies is an interdisciplinary subject and has a number of core concepts of which students are required to demonstrate knowledge, and understanding of how they are applied. Among them is also what are known as threshold concepts, and these are concepts that are “‘conceptual gateways’ or ‘portals’ that lead to a previously inaccessible, and initially perhaps ‘troublesome’, way of thinking about something” (Meyer and Land Citation2005, 373). Coined by Meyer and Land (Citation2003, 1), the authors describe these concepts as “akin to a portal, opening up a new and previously inaccessible way of thinking about something. It represents a transformed way of understanding, or interpreting, or viewing something without which the learner cannot progress”.

The key word is transformation: how the student's understanding of a subject has changed, or even their assumed values and norms may now be questioned and changed as a result of this exposure to threshold concepts. Neither is the change a bland and tranquil process: a student may find the experience to be “irreversible (unlikely to be forgotten, or unlearned only through considerable effort), and integrative (exposing the previously hidden interrelatedness of something)” (Meyer and Land Citation2005, 374). Furthermore, Meyer and Land (Citation2005, 374) caution that threshold concept can be “troublesome and/or they may lead to troublesome knowledge for a variety of reasons”. Since feminists and feminisms have a long history of bringing about disruptions, contestations, and challenges to assumed canons of development knowledge and practices (Batliwala Citation2007; Cornwall Citation2007; Jolly Citation2023), I argue that troublesome knowledge is key to gender and development studies, and that intersectionality, participation, and reflexivity are among the threshold concepts that students need to understand and experience at both an intellectual and emotional level. In the next section, I will explain why these theories and practices are considered threshold concepts.

Threshold concepts in gender and development

As a feminist and GAD educator, my focus is on linking students from the personal to the political, so that key concepts and theories can be understood from the ground up. In other words, words such as “intersectionality” and “participation” are not just printed words on paper – how do they affect stakeholders, beneficiaries, and donors in development? Who gets to participate? How do individuals’ and groups’ identities and social categories affect their development outcomes? How can reflexivity about development can be achieved by students, if they have few prior experiences of development practice? In particular, I have been concerned about the evaporation of meaningful gender and intersectional analysis, as students go through the superficial exercise of writing essays on their privilege and identities without connecting them with tangible, personal experiences, and emotions on power relations and humility.

In the classroom, learning about intersectionality from Crenshaw's influential articulation of the concept was a relatively easy process. In Crenshaw's canonical essay (Citation1989), she invited the reader to think of intersectionality as standing at a crossroads, with the different identities representing the different traffic going through – and how one's different identities can bring about nuanced experiences of oppression and, sometimes, privileges as well. One of the key contributions of Crenshaw, and other early proponents of intersectionality, is to move away from the essentialised category of “women” and to recognise how gender interacts with race, class, sexual orientation, and other social identities which give individuals and groups different experiences of access, marginalisation, and privilege (Nash Citation2008).

Although intersectionality was initially developed and applied within the North American context by Black feminists to explore how discriminations function across social categories of gender and race (hooks Citation2000), over the years, intersectionality as a concept has also been taken up in development studies and practices. For example, intersectionality has been used as an analytical framework to:

explore identity-based claims (Grünenfelder and Schurr Citation2015) as a way to highlight gendered experiences of food security and the role of kinship and age (Kimanthi, Hebinck, and Sato Citation2022)

examine the lived experience of Ethiopian women with disabilities and how they use peer support and dialogue to advocate change (Katsui and Mojtahedi Citation2015)

understand how intersectional identities can be chosen by those in power to include, exclude, or decide who has the right to speak; what topics are deemed worthy to pursue in development; or how gender equality should be defined (Wu Citation2022).

While students can readily understand how intersectional oppression functions if one is, for example, a poor illiterate woman in the Global South, it is harder to understand how oppression and privilege can simultaneously occur for an individual/group of people. Students readily engage in a critical analysis about how donors, international organisations, and corrupt governments reinforce colonialism. However, they have a harder time processing the notion that a local female politician, who might have struggled against the glass ceiling and gendered norms throughout her political career, would opt for policies and projects that worsen the condition of local women and girls. Similarly, while students may be able to distinguish different forms of intersectional identities and list the range of oppressions attached to each category, they are less able to comprehend what happens when these identities intersect, and how context plays a part in shaping the power relations. In other words, students understand intersectionality as an abstract concept, or as a “checklist” of oppressions, but are less able to comprehend intersectionality as a cohesive, messy, and context-bound social framework.

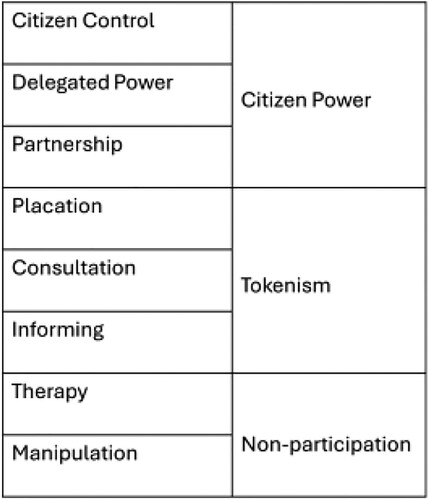

In contrast, the theory and practice of participatory development have been popular with my students throughout the years. In particular, they have found Sheryl Arnstein's ladder of citizen participation (see ) to be a powerful way of visualising and understanding the different forms of participation, and that not all forms of participation can have good intentions nor bring about positive change.

Figure 1. An adaptation of Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation. Sherry Arnstein's ladder of citizen participation, adapted from the article Arnstein (Citation1969).

For example, students are sceptical about the capacity of microcredit loans to increase poor women's participation in livelihood and income generation, as they readily unpack the exploitative and coercive dimensions of microlending. All students regard the top rung of the participation ladder (i.e. citizen control) as the ideal; however, they are less certain how this can be achieved, and whether the control of resources and decision-making is permanent, or can bring about meaningful changes to inequalities.

Faced with these pedagogical challenges, which go beyond asking students to memorise content, I created and refined a roleplay group assessment that runs over four weeks throughout the teaching term, using intersectionality and participation as the key threshold concepts to be learned, experienced, and felt. In the following section, I will present the case study based on three years of classroom observation, discussions with students, and a personal teaching diary.

A quick note on feelings and emotions: As a “gender person”, I have found that within the aid sector, there can be a temptation to view development concepts, methods, and practices as “doing good and feeling good”. This can become a compelling narrative that shuts down feminist critiques and seeks to exert itself as the normal experiences and feelings for all (Wu Citation2022). A feminist response to this in the classroom is to facilitate opportunities for students to experience, within a safe space, all the ranges of emotions that come with the troublesome knowledge of development. In this, I hope that students can have a more complex and nuanced education about development, and how why a self-reflexive feminist lens can help in their journey of discovery.

Roleplay as an integration of threshold concepts into a GAD classroom

The idea of a roleplay group assessment came to me in May 2020, when the global pandemic resulted in the shutdown of on-campus learning, and the rise of Zoom and other online platforms used for teaching. The students were attending these online classrooms from their bedrooms, in the quietest spot they could find in a cramped apartment, or wherever the internet connection was strongest. Some were international students who were stranded overseas or in their home country, others tried to strike a family–work–study balance as they assisted their own children's online learning from home. Regardless of their circumstances, all were feeling high levels of anxiety and uncertainty and, for most, coming to the online class was an opportunity to meet other people and have a momentary reprieve from the “real-world”.

In addition, as Pavey and Donoghue (Citation2003, 7) explained, roleplay has the benefit of getting “students to apply their knowledge to a given problem, to reflect on issues and the views of others, to illustrate the relevance of theoretical ideas by placing them in a real-world context, and to illustrate the complexity of decision-making”. It is also compatible with inclusive learning since roleplay is a collaborative learning process that can foster critical thinking, teamwork, and diverse perspectives (Okenwa-Emegwa and Eriksson Citation2020).

I then developed a roleplay exercise, which is as follows:

Students are given a two-page background brief about an imaginary island, Sossa. Sossa is located somewhere in the Pacific and was badly affected by the 2023 earthquake and subsequent tsunami. People have been displaced, there were reports of sexual and gender-based violence, and waterborne diseases are rife. The local population is frustrated by the slow disaster-relief and recovery efforts, and the newly elected government (after years of an authoritarian regime) is overwhelmed. Amidst this crisis, it was discovered that Sossa Island has a rare mineral that has similar properties to tantalum (a highly ductile metal used in mobile phones and other electronic devices). Dubbed “Cotium” after the sacred Mount Cota, this quick change of fortune led to the Sossa Government inviting an international mining company to negotiate mining terms and conditions. The local community is excited about the Cotium discovery, but also apprehensive about the fate of their beloved Mount Cota. The local community is supported by an international non-government organisation (NGO), who has been working in Sossa for decades on WASH-related issues.

Students in the class are divided into four groups: the Sossa Government, the community, the WASH NGO, and the mining company. Each group is given a private dossier about the group's identity, background, and suggested priorities that they might like to take up and advocate for. Students are allocated time to meet in their groups to develop their agenda, demands, and strategies.

Over the four weeks, students meet in their roleplay identities to negotiate desired outcomes for their interest group. I act as an impartial facilitator for the negotiation and provide no advice or instructions aside from ensuring each party has equal time to speak, and that the negotiations are conducted in a robust but civil way.

Threshold concepts, such as gender, intersectionality, and participation are taught in the course before the commencement of the roleplay assessment. The assessment rubric, as well as the background briefs, provides clear information to the students about what assessment learning outcomes are expected. However, I make a conscious decision not to mark students based on the outcome, because I do not want to pressure students to produce an artificial and “positive” outcome since the key learning is about the processes of considering how power functions through intersectionality, and how participation might be encouraged or stymied.

Each week, students are invited to reflect on how intersectionalities of class, Indigeneity, race, non/citizenship, and gender play a role (or not, as is sometimes the case) in the negotiations. In the final week of negotiation, the groups are also not expected to “finalise” an agreement; rather, they are given a significant degree of freedom to decide how the scenario will play out, so long as each group behaves within the realistic confines of the roleplay context. Students are also required to submit a reflection paper about their experience, and how the key threshold concepts functioned in the roleplay.

The roleplay storyline changes each year. For example, in 2020, it was about the local community negotiating with the local government and the opposition party on COVID-19 lockdown policies and reliefs; in late 2021, the students roleplayed as the Australian Government, the Taliban, and a coalition of NGOs to negotiate the release of 20 Afghan women activists. For the latter, students were consulted on the storyline and had a say on the general theme, to ensure that no one felt unsafe because of the topic.

Students’ learning experiences of the threshold concepts through roleplay

Participation – students observed that those who roleplay as the government, or other categories who are in a position of power (e.g. the government and the opposition party) tend to dominate the discussions, while those in the “community” groups have to fight for their demands to be taken on board. In my observation, sometimes the negotiations can become a bilateral conversation between the government and the mining company, while the community and NGO are desperately trying to interject but are told “We will get back to you”. In one dramatic outcome, the community threatened to throw out the government and take control. This resulted in a quick concession from the government, and the mining company was able to use the distraction to obtain a smaller mining tax than what was agreed upon.

The roleplay scenarios are carried out in high-stakes, real-time dynamics and the students engaged with the task seriously; they also had a lot of fun. The mining company's attempt to be gender equal by promising mining equipment designed for women's hands was met with derisive laughter. In another class, the government announced that the disaster-relief targets had all been met, to which one community member furiously shouted, “Where is my new house? We’re still sleeping in tents!” The WASH NGO tried to highlight the environmental impacts of mining, only to be told their permit to work in the country is under review. These instances are not trivialising actual cases of humanitarian crises or Indigenous land rights, but rather, students are bringing their insights and experiences to enhance the realism of the roleplay.

Students’ reactions

Overwhelmingly, and based on informal (tutorial discussion) and formal (the reflection essay and the university course evaluation survey) feedback, students enjoyed the roleplay assessment. They found the weeks of preparation, negotiation, and manoeuvring for better outcomes helped them to grasp the concepts of intersectionality and participation. Students reflected on the challenges of representing women and under-represented groups when the power dynamics meant governments and mining companies’ interests predominate. Those in the government groups were concerned about how they were too busy “governing” to consult with the local communities, especially on cultural sites and Indigenous women's perspectives. The mining company students discussed their conflicts of conscience between toeing the company's mandate and profit-chasing, while witnessing the outcomes of their actions upon the Sossa communities. The NGO groups tend to express frustration at not being listened to by the government, and questions about environmental sustainability, gender equality, and efforts to implement a free, prior, and informed consent process were sidelined.

Despite the roleplay being on an imaginary Pacific Island, the exercise showed the challenges of trying to apply intersectionality and participatory development concepts, due to the power imbalance among the four groups. Students were emotionally invested in the negotiations, and they often hung around after the class, animated in their post-analysis of what happened, and expressed a mixture of outrage and amusement at how such injustices could occur. Through roleplay activities, students experience the complexities of power dynamics, privilege, and oppression in development scenarios, fostering critical thinking and empathy. A breakthrough that shows students understanding intersectionality and participation as threshold concept is when students reflect on their realisation that inclusive development's values must be embodied in their practice. As one student said, “When I become a development worker, I hope I will remember this lesson and be empathetic to the communities, and not get caught up in the process of doing aid.” Another student recognised that while inclusive development can be inspirational, it is also important to ensure words like participation or intersectionality are not depoliticised as buzzwords.

For educators interested in implementing this roleplay, there are a few considerations:

– Optimally, there should be no more than 30 students, so that each group has six or seven students (too few and the workload may be onerous, and too many means it can be hard for students to work effectively as a team) and the facilitation of the dialogues will be easier to manage.

– For students with special needs (e.g. with a disability), it is important to check with them at the start of the term to see if they require additional support (e.g. I work with the team to ensure the student with special needs can participate equitably). Where necessary, a substitute assessment is provided, and the type of assessment is comparable to the course learning outcomes.

– Students who come from a rote-learning education system, or those with a more introverted personality, may find the assessment confronting. I designed the assessment rubric to focus on teamwork, and how each team member can contribute through their unique capabilities, so that students who are reluctant to debate and argue with other teams can make equally important and meaningful contributions such as preparation of the talking points, note taking, and analyses, as well as providing moral support to the speaker/s in their team.

– Ensuring there is sufficient time to debrief and talk about what happened after each round of the negotiation can help remind students that this is an imaginary scenario, and to take a step back from the roleplay. On the whole, students relish the chance to be actors and to have fun.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the special issue guest editors for their support, and the peer reviewer for their helpful and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 For example, a policy about disaster response and recovery may call for service providers to consider the needs of diverse groups and proceed to list them. However, there is no mention in the policy about how service providers might best support these vulnerable groups, or the repercussions if they are excluded from access to support. Instead, it is the “listing” of diverse and vulnerable groups which is seen to have demonstrated consideration about intersectionality, rather than the creation of a robust policy on how to support them. For an insightful case study and analysis of this issue, please refer to Corinne Mason's article in the bibliography.

References

- Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 2007. “Taking the Power Out of Empowerment: An Experiential Account.” Development in Practice 17 (4-5): 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469559.

- Cornwall, Andrea. 2007. “Buzzwords and Fuzzwords: Deconstructing Development Discourse.” Development in Practice 17 (4-5): 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469302.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalising the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1:8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Grünenfelder, Julia, and Carolin Schurr. 2015. “Intersectionality – A Challenge for Development Research and Practice?” Development in Practice 25 (6): 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1059800.

- hooks, bell. 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Centre. London: Pluto.

- Jolly, Susie. 2023. “Is Development Work Still so Straight? Heteronormativity in the Development Sector Over a Decade on.” Development in Practice 33 (4): 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2022.2115012.

- Katsui, Hisayo, and Mina C. Mojtahedi. 2015. “Intersection of Disability and Gender: Multi-Layered Experiences of Ethiopian Women with Disabilities.” Development in Practice 25 (4): 563–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1031085.

- Kimanthi, Hellen, Paul Hebinck, and Chizu Sato. 2022. “Exploring Gender and Intersectionality from an Assemblage Perspective in Food Crop Cultivation: A Case of the Millennium Villages Project Implementation Site in Western Kenya.” World Development 159:106052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106052.

- Mason, Corinne L. 2019. “Buzzwords and Fuzzwords: Flattening Intersectionality in Canadian Aid.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 25 (2): 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/11926422.2019.1592002.

- Meyer, Jan H. F., and Ray Land. 2003. “Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising Within the Disciplines.” In Improving Student Learning: Improving Student Learning Theory and Practice – Ten Years On, edited by Chris Rust. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

- Meyer, Jan H. F., and Ray Land. 2005. “Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge (2): Epistemological Considerations and a Conceptual Framework for Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education 49 (3): 373–388. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068074.

- Nash, Jennifer C. 2008. “Re-thinking Intersectionality.” Feminist Review 89: 1–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40663957.

- Okenwa-Emegwa, Leah, and Henrik Eriksson. 2020. “Lessons Learned from Teaching Nursing Students about Equality, Equity, Human Rights, and Forced Migration through Roleplay in an Inclusive Classroom.” Sustainability 12 (17): 7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177008.

- Pavey, Juliette, and Danny Donoghue. 2003. “The Use of Role Play and VLEs in Teaching Environmental Management.” Planet 10 (1): 7–10. https://doi.org/10.11120/plan.2003.00100007.

- Wu, Joyce. 2022. “‘Doing Good and Feeling Good’: How Narratives in Development Stymie Gender Equality in Organisations.” Third World Quarterly 43 (3): 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2030214.