ABSTRACT

Climate resilient development is increasingly used as the catchcry of donors and development partners globally as a response to the risks climate change poses to sustainable development. Some development organisations are progressing climate resilient development by integrating climate risks within their strategies and practices, recognising the interlinkages between climate change, poverty, injustice, and inequality. However, many development organisations that do not hold climate change as a core programming focus are yet to take steps towards climate resilient development. While language about “climate risk integration” and “climate-proofing” is commonly used in the development sector, practical first steps on how to enact such approaches remain elusive. This paper describes how a development program without a core focus on climate change has taken initial but important steps towards climate resilient development. Lessons from the Australian Volunteers Program’s efforts in climate risk integration may help to inform and support other organisations in similar positions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate resilient development

It is well established that climate change influences every aspect of sustainable development, with climate change impacts having the potential to undermine the achievement of all the sustainable development goals (Fuso Nerini et al. Citation2019). Climate change poses major risks to sustainable development by causing substantial damage, unrecoverable losses, and widespread impacts on ecosystems, human lives, infrastructure, and societies across the globe (IPCC Citation2022). Efforts to adapt to climate change are therefore critical, in parallel with efforts to mitigate emissions of greenhouse gases that are driving climate change. From global to local levels, efforts are increasingly being made to consider and adapt to the risks of climate change as the impacts become harder to ignore. Addressing climate change is also a human rights issue because of its pervasive nature and links with poverty, justice, and inclusion (UNFCCC Citation2016).

As a holistic global response to climate change, all organisations working on humanitarian and development issues need to integrate climate change into their strategies and practices (Hewitt, Mason, and Walland Citation2012). Evidence from Australia points to the need for further support for humanitarian and development organisations to take action on climate change. For example, Australia’s peak body for non-government organisations – Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) – responded to member requests for support on climate action, with requests coming primarily from its non-climate-focused members. ACFID responded by developing a Climate Action Framework (see Davies and Koff Citation2021), guiding documents and case studies (see Gero, Chowdhury, and Winterford Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Gero and Chowdhury Citation2023) and facilitating a peer learning program to support members to take meaningful action on climate change. The scalability of research findings presented in this paper is therefore considered significant in Australia and potentially other countries where humanitarian and development organisations may face similar challenges of climate integration.

Mainstreaming, or integrating climate change considerations into sectoral policy and programming, gained traction in the early 2010s, with a growing evidence base supporting this approach (Lebel et al. Citation2012). Integrating climate change into development programming means consideration of how development programming could exacerbate or reinforce the impacts of climate change. It also means consideration of how climate change risks and impacts could undermine development outcomes. Integrating climate change involves applying this “climate change lens” to all aspects of policy and planning processes – from strategic planning to design to operations and implementation of programs. The alternate approach to integration or mainstreaming is specific climate change policy or programming. An example of a specific climate change program is the Pacific–Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning program, which ran between 2012 and 2014 and focused specifically on updating climate projections and implementing adaptation activities.

The goal of climate change integration is to take a climate risk-informed approach to development planning and ultimately implement a climate resilient development approach (Opitz-Stapleton et al. Citation2019; Pokrant Citation2016). Sectors including critical infrastructure, agriculture, public health, and urban planning are all active in mainstreaming, or integrating, climate change considerations into policies and practices (Runhaar et al. Citation2018). This is particularly the case because the intersection of climate change impacts with these sectors is particularly visible – and often, the business case for integration is easily justified. Integrating climate change into policies and practice has benefits, including:

Multiple and reinforcing benefits (e.g. ecosystem restoration has beneficial adaptation and mitigation outcomes as well as positive biodiversity and human wellbeing outcomes).

Economic and resource efficiency.

Risk-informed development outcomes.

Promotion of innovation enabled through inclusive and intersectoral collaboration.

There are also multiple challenges surrounding climate resilient development, particularly for organisations without a core programming focus on climate change. These challenges include (Ranger, Harvey, and Garbett-Shiels Citation2014):

Lack of awareness of climate risks within organisations.

Lack of experience in, and documented evidence of, “future proofing” organisations and programs.

Resource constraints (e.g. lack of technical expertise, time, and financial resources).

Short duration of many development programs and projects.

Lack of long-term monitoring and evaluation systems for adaptation and resilience.

Lack of incentives to integrate climate resilient development actions and programs.

Ranger, Harvey, and Garbett-Shiels (Citation2014) notes that planning and policy making processes are often slow to react to changes in the external environment. Lagging global and organisational responses to climate change are a clear demonstration of this.

1.2. Climate change and international volunteering

The intersection of international volunteering and climate change has been a growing topic of discussion for over 16 years, with the International Forum for Volunteering in Development (Forum) engaging in critical reflections on the topic in 2007 (see Brook Citation2007), 2010 (see Mulligan Citation2010), and 2020 (see Allum et al. Citation2020, and further discussion below). The 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties also prompted broader discussions of the volunteering and climate change nexus, where those connected to volunteering for international development began to recognise the importance of climate change (Allum et al. Citation2020).

At the 2020 annual International Forum for Volunteering in Development conference, climate change was the central theme. At this conference and past events, volunteering organisations voiced concerns that not enough was being done in the volunteering sector to address climate change (Allum et al. Citation2022). The dialogue from the 2020 Forum conference also highlighted that volunteer organisations need to consider climate change as a cross-cutting issue within different humanitarian–development priority areas, instead of it being seen as a separate program area (Allum et al. Citation2020). International volunteering agencies and thought leadership within the sector recognised the need to consider the carbon footprints of volunteering programs (Allum et al. Citation2022). This is particularly relevant given the carbon emissions from air travel associated with international volunteer programs. However, the 2020 Forum Conference also prompted member organisations to consider climate change in broader and more integrated ways as well. Learmonth (Citation2020) authored a paper as a contribution to the conference and identified eight opportunities members could consider to strengthen their work in volunteering for climate action. A more recent Forum publication (see Forum Citation2022) situated climate change as a wider trend the international volunteering community needs to tackle. While some examples of “how” to tackle climate change within volunteer organisations and programs are mentioned in these publications, the suggestions are neither tailored to specific Forum member organisations nor comprehensive enough to give organisations the confidence to take the first step.

This recent and ongoing dialogue reflects the international volunteering sector’s recognition that even without a direct climate change focus relevant to volunteering efforts, the sector has a role in integrating climate change considerations at an organisational level.

1.3. The Australian Volunteers Program

Since the 1960s, the Australian Government has supported Australians to volunteer in lower- and middle-income countries. The Australian Volunteers Program began in 2017 and represents the Australian Government’s current support for international volunteering. The program is managed by Australian Volunteers International (AVI), an Australian non-profit organisation, in collaboration with two private international development firms (DT Global and Alinea International) (Australian Volunteers Program Citation2021).

1.4. The Australian Volunteers Program and climate change

The Australian Volunteers Program developed a Global Program Strategy, which provided an important starting point for considering climate change within the program (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade & Australian Volunteers Program Citation2018). Climate change, disaster resilience, and food security is one of three thematic impact areas identified in the Global Program Strategy, along with Human Rights and Inclusive Economic Growth. The impact areas are seen as a lens to assess the contribution of the Australian Volunteers Program, and Climate change, disaster resilience and food security is included given its priority as a foreign policy issue of the Australian Government (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2017).

In 2019, DFAT released its Climate Action Strategy which notes: “Australian development assistance supports the goals of the Paris Agreement to address climate change and strengthens socially inclusive, gender responsive sustainable development in our region” (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2019, 4). The Climate Action Strategy also notes the importance of integrating climate change across Australia’s development program. The Climate Action Strategy helped the Australian Volunteers Program to set an important strategic directive to continue integrating climate change at different levels within the program and across different sectors (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2017; Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade & Australian Volunteers Program Citation2018). More recently, the Australian Government’s International Development Policy (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2023) further clarifies climate change as a core consideration of the aid program, with calls for increasing climate investments to better address climate risks. This new policy provides an additional incentive for the Australian Volunteers Program to more firmly embed a climate resilient approach within its operations and programming.

Past efforts within the Australian Volunteers Program have touched on climate change as an important issue affecting volunteer assignments and program operations. For example, the Australian Volunteers Program contributed to progressing partner organisations’ climate change and disaster resilience objectives through skill-sharing and awareness-raising activities. The Australian Volunteers Program is also offsetting carbon emissions from air travel and has done so since 2019. While starting as an alternative volunteering modality during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote volunteering has represented a lower-carbon modality of volunteerism, and the program is continuing to promote remote volunteering and hybrid volunteering (a mix of remote and in-country volunteering) as effective and low-carbon modalities following the global pandemic. These early efforts demonstrated the interest and appetite of the program to integrate climate change considerations. However, the Australian Volunteers Program recognised there was still work to do to more genuinely embed climate action as a mainstreamed and ongoing core area of concern for the program. Given the strong push for climate resilient development, but little guidance on how to implement it, this paper details how the Australian Volunteers Program, representing a non-climate change-focused program, took steps to integrate climate change in practical and relatively low-cost ways and the benefits of doing so.

There are three key, interconnected areas where the program has influence and could promote a climate resilient approach. One is the partner organisations the Australian Volunteers Program supports. Many partner organisations have climate action as a significant organisational objective (typically around ten per cent of the partners supported each year, or 25 unique organisations supported during 2022–2023; Australian Volunteers Program Citation2021). The contribution the program has made to these organisations and their work on climate action has been documented (CoLAB Consulting Citation2020; Gero et al. Citation2021) and is largely out of scope for this paper. The second area in which the program could promote climate resilience is the involvement of volunteers. Research has shown the positive impact assignments can have on volunteers, including promoting greater awareness of and interest in global development issues and foreign policy and supporting individuals to make positive changes in how they live their lives after their assignment (Fee et al. Citation2022). It might be assumed that includes a greater awareness of climate change for at least some volunteers. However, the evidence does not provide that level of granularity on areas of interest to volunteers, and this is not the principal focus of the current study. The third and primary area where the program can promote a climate resilient approach is through its own operations, systems, and policies. While ultimately hoping to extend beyond this in future, the program’s own activities were the starting point of its climate journey and the focus of this paper.

2. Background to action research with the Australian Volunteers Program

The research presented in this paper was informed by an earlier evaluation of the Australian Volunteers Program’s Climate change, disaster resilience and food security thematic impact area conducted by the University of Technology Sydney, Institute for Sustainable Futures (UTS-ISF) in 2021. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the outcomes and contribution of the Australian Volunteers Program to the Climate change, disaster resilience, and food security impact area. Informed by the evaluation findings, ten practical and strategic recommendations were provided to the Australian Volunteers Program and DFAT. A specific recommendation for the Australian Volunteers Program was to “begin to consider integrating climate change and risk-informed development within volunteer assignments, in line with DFAT policy to integrate climate change across the government’s development assistance program” (Gero et al. Citation2021, 47). The Australian Volunteers Program took action to address this recommendation by developing a set of activities and approaching UTS-ISF for implementation.

3. Methods

This section describes the action research approach taken by the Australian Volunteers Program and UTS-ISF to learn about effective ways to integrate climate action in operations and programming methods. Action research is a method that aims to investigate and take action at the same time (George Citation2024). The key principles of action research include (i) Collaboration: engaging diverse stakeholders in the research process; (ii) Reflection: collectively considering actions and outcomes; (iii) Practical focus: addressing problems and identifying tangible solutions; (iv) Flexibility: designing research methods appropriate for the research context and meeting the needs of research (Reason and Bradbury Citation2001). Action research can facilitate organisational learning and help organisations to develop more effective and efficient practices through participatory and reflective processes (Reason and Bradbury Citation2001).

This research aimed to explore how the Australian Volunteers Program is integrating climate action in organisational operations and programs, while providing evidence and recommendations for future integration practices. This twin-track approach of investigating and problem-solving makes action research a suitable research methodology for this specific research. Guided by the research objective, the Australian Volunteers Program and UTS-ISF worked in collaboration, co-designed research methods, and reflected on the research outcomes to draw on effective learning and insights. This approach aligns with the principles of action research and contributes to the Australian Volunteers Program’s organisational learning. Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Technology Sydney’s approval process (UTS HREC REF NO. ETH21-6538), and informed consent was gained prior to primary data collection.

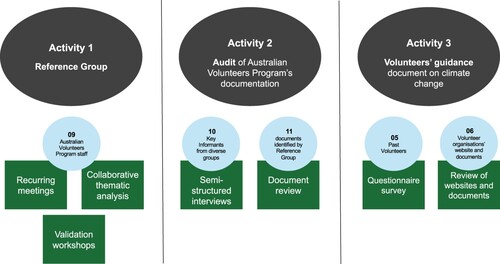

Three areas of work were selected to support the program: intentional learning, reflection, and capacity building (Activity 1: Reference group to guide the research and maximise learning, capacity building and uptake of findings); an audit of existing knowledge and exploration for continued improvement (Activity 2: Audit of Australian Volunteers Program’s documentation); and a trial of a small-scale yet strategic activity towards progress (Activity 3: Volunteers’ guidance document on climate change). These three activities used different methods as part of the action research. The methods used under each activity are depicted in and described below.

3.1. Activity 1: reference group to guide the research and maximise learning, capacity building, and uptake of findings

The research activities were overseen by a reference group of nine Australian Volunteers Program staff. Importantly, the reference group had strong support from senior leadership within the program. Past research notes the importance of strong leadership to guide cultural change within an organisation (Ranger, Harvey, and Garbett-Shiels Citation2014); thus, the leadership support was a critical foundation of the activity.

The reference group members were purposively selected given their interest and experience working on climate change activities with the Australian Volunteers Program or in previous work roles. The purpose of the reference group was to ensure research approaches, findings, and recommendations emerging from the research aligned with the expectations and scope of the program and to provide cross-program engagement and support. Reference group members included in-country staff who were embedded in the local contexts where partner organisations hosting volunteers operate. Partner organisations and volunteers were not included in the action research, given this was the first step the Australian Volunteers Program was taking along their climate integration journey, and the scope was, in this first instance, primarily internal Australian Volunteers Program volunteering management. However, the important role partner organisations play and the potential for volunteers to amplify climate messaging was a high priority throughout the research, as noted throughout the paper.

To maximise learning, capacity building, and end-user uptake to achieve maximum impact, UTS-ISF and the reference group took a collaborative approach to analysis and sensemaking of emerging findings. Recurring meetings between the reference group and UTS-ISF were held throughout the action research, enabling reference group members to remain updated on activities and progress and engage in emerging findings. An online sensemaking workshop was held to share and validate emerging findings. The workshop included participatory activities to gain insights from reference group members in relation to emerging findings.

3.2. Activity 2: Audit of Australian Volunteers Program documentation

The purpose of the audit was to answer the following guiding research questions:

Where is climate change already included in the Australian Volunteers Program’s existing documentation?

Where should climate change be included in the Australian Volunteers Program’s existing documentation?

At what level of the program, e.g. organisation level, program level, regional, country, volunteer assignment level?

What are the preferred entry points for integrating climate change into the Australian Volunteers Program’s existing documentation?

The audit activity was led by UTS-ISF and comprised the collection and analysis of primary and secondary data. Primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews. The reference group nominated program staff and external stakeholders who were identified as being important in providing their views (i.e. their role in the organisation) and/or having worked on climate change-related projects. Ten individuals were recruited for the key informant interviews through a purposive sampling method informed by these criteria. Nine interviews with ten individuals were conducted across three stakeholder groups, including eight Australian Volunteers Program staff based in Australia, Pacific, and South Asian region, one consultant with prior experience working with the program and one representative of Australia Pacific Climate Partnership (a DFAT program in the Pacific focusing on climate change and disaster resilience integration across Australia’s development program). A semi-structured interview guide was developed to identify where climate change is relevant to the Australian Volunteers Program, to understand the challenges of climate change integration, and to explore ways to support program leadership for climate change integration. Interview notes were analysed based on the guiding questions noted above.

The reference group also identified and collated existing guidance, documentation, and volunteer learning materials from the Australian Volunteers Program for a document review. A total of 11 documents, including DFAT’s Climate Action Strategy, Australian Volunteers Program In-country Orientation Program presentations and multiple other documents (e.g. country security plans, volunteer assignment guides, country profiles, and country program plans) were reviewed as part of the activity. The documentation was assessed to identify (i) the extent to which climate aspects were mentioned or considered and (ii) how climate information was presented in the documents. Findings across the interviews and literature review were discussed in detail with the reference group and presented back to the Australian Volunteers Program in a summary report.

3.3. Activity 3: volunteers’ guidance document on climate change

The action research involved trialling a small-scale, strategic activity to demonstrate where a “quick win” on climate change integration could be achieved. With the support and oversight of the reference group, UTS-ISF researchers developed guidance for volunteers to increase their knowledge of climate change and understand the relevance of climate change in their volunteer assignments. This activity was informed by two research methods, drawing on primary and secondary data. Primary data were gathered through an emailed questionnaire to past volunteers. The reference group provided a list of past Australian Volunteers Program volunteers who were deemed able to provide insights into climate change integration based on their assignment objectives. Thirty-two individuals were emailed a questionnaire, with five responding (a response rate of 16 per cent). Four open-ended questions were included about how climate change has been integrated into different international volunteer programs. Respondents were asked to identify focus areas in the guidance documents that would be most appropriate for the Australian Volunteers Program context.

A literature search was conducted to identify existing documentation on climate change from different international volunteer programs. Given the limited academic literature published on this topic, the search strategy primarily involved grey literature. Documents were sourced via web searches targeting five volunteer programs/organisations known to be sending volunteers on international assignments, for example, Red Cross Volunteers, United Nations Volunteers, Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (JICA), Peace Corps Volunteers, and Canadian Volunteer Cooperation Program. A primary scanning process was undertaken to identify the most relevant documents and content (e.g. web pages, policies, strategies, and plans). Documents and websites of the five organisations were analysed. The selected documents were analysed to understand how climate change was described within the volunteer program documentation. These findings validated the evidence from the interviews to inform the structure and content of volunteer guidance.

Analysis of findings from the questionnaire and document review supported the drafting of the guidance document for volunteers, which was undertaken through a collaborative approach between UTS-ISF and the reference group. Several iterations of the draft were shared with inputs provided by reference group members. Recurring meetings also ensured the document was relevant to volunteer activities and appropriate for orientation and pre-assignment briefings for the Australian Volunteers Program. Following this collaborative activity, the volunteer guidance has been used by the program, but it was beyond the scope of the research project and also this paper to assess its use and impact on strengthening climate change integration.

3.4. Limitations

The research did not involve any representatives of partner organisations. While this could be seen as a limitation, it was decided to limit efforts to internal stakeholders within the Australian Volunteers Program. This was consistent with the primary focus of the work and aimed to engage those most needed to bring about internal change. Another challenge with action research is disentangling the findings from the process compared to the findings from the methods. Results are presented in Section 4 for both aspects, with each offering useful insights for other non-climate-focused organisations.

4. Results

This section shares how the action research process, key results, and outputs have enabled the Australian Volunteers Program to begin integrating climate change within the program.

4.1. Collaborative and participatory research supported effective integration

The project’s collaborative and participatory approach has supported progress towards climate resilient development within the Australian Volunteers Program. Several forms of collaboration and participation included senior management support, the reference group, and the key informant interviews.

First, the Australian Volunteers Program committed to an activity to drive forward climate action integration. The program’s senior management supported a dedicated research project to progress climate change integration at strategic, programmatic, and operational levels of the organisation. The research design was intentional and committed to ensuring participation among different organisational levels. Through the intentional participation of diverse organisational representatives, each individual was able to engage with each other and the UTS-ISF research team to explore the implications of current and future practices related to climate change. The active participation in the research inquiry provided learning opportunities for individual staff members across the program.

Second, the research involved a diverse and inclusive reference group, which supported effective climate action integration. The reference group had representation from Australia, Asia, and the Pacific regions, with diverse roles and responsibilities within the program, including representatives from the country and regional management levels and the monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) team. The diversity within the reference group enabled the identification and inclusion of various documents for review, including different country-level documentation, such as Tonga’s Country Program Plan and Sri Lanka’s In-country Orientation Program documents.

The reference group reflected on preliminary findings of the research and shared their experience and insights through online sensemaking workshops and meetings. Their perspectives helped to navigate appropriate integration approaches for different levels of the program in diverse geographical contexts. The reference group’s engagement in the drafting process of the volunteer guidance was also collaborative and participatory, which ensured the output was fit for purpose for the volunteers.

Third, the interviews enabled broad engagement with selected stakeholders, which helped to reveal the Australian Volunteers Program’s organisational practices and provided an empirical basis and recommendations to explore different entry points of integration. The interviews were designed to understand individuals’ perspectives on climate change integration, where climate change is more relevant within the program, and what incentives might drive further progress.

The interviews provided evidence that the program’s climate change integration should be holistic and complementary to available resources of the program. All ten interviewees, representing diverse organisational levels, supported the prioritisation of climate change in the next Global Program Strategy. The interviewees agreed on the benefits of properly resourcing climate change integration, rather than having it as an “add on” to existing workloads. Most interviewees also noted that in-country management teams do not have climate change expertise and, therefore, require additional support to build capacity for integration. Most interviewees also emphasised the necessity of supporting leadership to coordinate integration practices across the program.

The interviewees also proposed achievable and effective ways of integration at an operational level. For example, some interviewees suggested including sections on climate information in the volunteers’ pre-departure briefing and In-Country Orientation Program (ICOP) documents as an integration effort at an operational level.

The challenges of climate change integration were also identified and explored through the interviews. The interviewees raised some important challenges, such as limited resourcing for integration, competing attention among other priority areas, and overloading staff members and volunteers.

The findings from the interviews with a broad range of representatives across the program provided empirical evidence and recommendations to the program to identify realistic strategic directions and operationalise integration at the regional and country levels by using existing resources. Sharing the findings with the reference group helped to identify what was considered feasible for climate risk integration and helped validate entry points for action and “quick wins” (see Section 4.3).

4.2. An internal champion has promoted and accelerated integration approaches

Within the Australian Volunteers Program, an internal champion initiated and drove forward discussion and dialogue about climate change integration within the Australian Volunteers Program. The program does not have internal resources or a designated climate change adviser within its organisational framework. However, the internal champion identified and prioritised climate change considerations and recognised the need for integration at strategic and operational levels. The internal champion took initial steps to facilitate climate change integration approaches and worked towards influencing organisational change. This was achieved by raising the issue with senior management, through conversations with staff in the organisation, and by initiating integration activities such as this project. This was all possible due to the supportive organisational culture and existing interest of program staff.

The program’s internal champion also led and supported the reference group and acted as a key communicator between UTS-ISF and the reference group. This shaped the project to deliver results and outputs that were most beneficial for the Australian Volunteers Program and provided recommendations and guidelines for contextualised integration approaches.

4.3. “Quick wins” using existing resources can demonstrate progress

The Australian Volunteers Program aimed to create a foundation and build momentum towards the climate change integration process. Therefore, the program selected activities that were quick wins, easy to achieve, and that could be consolidated within the organisational activities without overburdening the staff members and volunteers. The two main activities were the audit of Australian Volunteers Program’s climate change guidance, which supported an evidence base for next steps, and the development of volunteer guidance on climate change. These are described below.

4.3.1. Audit of Australian Volunteers Program’s climate change guidance

The audit provided an understanding of how the Australian Volunteers Program currently integrates climate change into its documentation and suggested practical ways of further integration. The audit provided evidence that integrating climate change into the program’s documents and guidance has already started, and plans are underway to continue this practice. Among the reviewed documents, four were identified where climate change was already integrated. These documents have diverse objectives and audiences. For example, DFAT’s Climate Change Action Strategy and the Australian Volunteers Program’s Global Program Strategy primarily inform senior leaders and management to outline organisational strategic plans, whereas Sri Lanka’s In-country Orientation Program (ICOP) document is used at the operational level.

Some documents were identified where a climate risk-informed approach could be made more explicit. For example, the Assignment Plan is an important volunteer assignment document with a section on Challenges and Risks. Reframing the existing section in relation to climate change was a simple and efficient approach to integrating climate change.

The document review also identified gaps in documentation where climate change considerations could be strengthened or included. For example, the Australian Volunteers Program Diversity and Inclusion Assignment Guide could note that climate change has a disproportionate impact on women and people with disabilities. The Environmental List document, a pre-assignment document for volunteers, could include a section describing ways for volunteers to reduce climate change impacts by reducing consumption of disposable goods and energy-intensive services. The Guide for Partner Organisations Working with Australian Volunteers could affirm that the Australian Volunteers Program would support partner organisations in reaching their development goals, including consideration of direct and indirect climate change impacts.

The document review also reinforced that documentation with clear guidelines for different stakeholders supports effective integration. Therefore, climate change integration should be targeted to different stakeholders relevant to the program, such as staff (especially in-country), partner organisations, and volunteers.

The reference group went on to work through actioning the list of recommendations described in the audit. As examples of further action, the program has since also introduced an online training module for staff and volunteers on climate risk-aware development, introduced environmental screening into the program’s procurement processes for all goods and services, developed short briefing notes for volunteers on the likely impacts of climate change in the countries they will be going to (based on World Bank Climate Risk Country Profiles; see https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country-profiles), and given greater focus to climate-specific impacts in country risk and security plans.

4.3.2. Volunteer guidance

The process of developing volunteer guidance was informed by a review of existing documentation from five volunteer programs/organisations known to be sending volunteers on international assignments. The review of documents and websites (see ) highlighted different volunteer organisations’ approaches and helped researchers understand how volunteers contribute to climate action initiatives within the scope of their respective organisations. For example, JICA actively engages in climate mitigation projects, while Red Cross focuses on disaster response and adaptation strategies, with future aspirations for mitigation. Peace Corps volunteers work on nature-based solutions, conservation, and reforestation. The findings from the review also provided a broader perspective on organisational viewpoints and strategic priorities regarding climate change. For example, Red Cross, JICA, and Peace Corps view climate change as a humanitarian and existential crisis. United Nations Volunteers focus on climate change to progress towards sustainable development goals, and the Canadian Volunteer Cooperation Program integrates climate action projects through Canada’s international development strategies. These insights enabled a better understanding of the diverse contexts and approaches of different volunteer organisations and helped researchers frame appropriate guidance for volunteers in the Australian Volunteers Program.

Table 1. Findings from document review.

Results from the volunteer questionnaire included the following points:

Increased visibility about climate change was recommended, including in volunteer role descriptions, available resources, and inclusion of climate change, more specifically, as a sector for prospective volunteers to search for.

Examples of the projected climate change impacts in the host country and at community level were proposed, as well as important factors about climate action that volunteers could consider in their assignments.

Having a range of resources in different formats to meet different needs (e.g. volunteers, POs) and having access to a climate specialist to provide more details of how projects might be impacted by climate change.

These findings point to the need for volunteer guidance to introduce volunteers to how climate change affects the countries in which they are volunteering, how their volunteer assignments might be impacted, and how they might respond as volunteers.

With the above results in mind, developing the volunteer guidance was an achievable and low-cost task, and it offered easy-to-understand messages about why climate change is an important consideration for volunteers during their volunteer journey. The volunteer guidance document provided an overview of climate change in the global context and Australia’s commitments to climate action, including mention of DFAT’s Climate Action Strategy. Importantly, the volunteer guidance also discusses how climate change can be a direct or indirect, or visible or invisible, issue for volunteer assignments, with practical examples. Further resources are included in the guidance for volunteers wishing to learn more about the links between volunteering and climate change.

The volunteer guidance was intended as a prompt and resource for the hundreds of volunteers who go on assignment each year. However, internally, it also served as a galvanising activity for the reference group, providing initial focus and an achievable objective that helped make the broad aim of “integrating climate change” more concrete. A small, clearly defined “quick win” served as a crucial prompt for further action. The audit (described above) and the volunteer guidance gave the reference group the confidence, and the internal legitimacy, to go a lot further in integrating climate change across program functions.

5. Discussion

Climate change integration within a system is often influenced by enabling factors that increase the capacity of integration through exploring different implementation actions and considering integration for different organisational levels (Gupta et al. Citation2010; Lawrence et al. Citation2015). This section highlights the enablers of climate change integration in the Australian Volunteers Program – both actors and actions, and how the enablers supported integration activities within the program, are discussed. Ongoing areas requiring attention for future progress are also discussed.

5.1. Enablers of success

5.1.1. Simple and easy to achieve activities to build momentum

The Australian Volunteers Program demonstrated that integrating climate change does not need to start with complicated, technical, or expensive activities of large scope. This finding aligns with results from a study of 133 Global Environmental Facility adaptation projects, which found that most actions are enabling and relatively inexpensive (Biagini et al. Citation2014). This is an important insight for other programs or organisations where climate change is not a core focus. For example, auditing the program documents was a small-scale, uncomplicated, yet important activity that enabled a trajectory towards climate change integration at strategic, programmatic, and operational levels and brought diverse people together across the program. Developing the Volunteer’s Guidance was also a small-scale and easy to achieve activity. However, the guidance has great potential to integrate climate change at an operational level by introducing climate change to the volunteers and showing them how they can think about climate change in their volunteer services. It also provides source material that the program can easily adapt for different purposes.

5.1.2. Broad organisational support, including from senior management

The literature strongly supports the need for senior management and board-level support for genuine climate action to occur in organisations (e.g. see Yuriev and Boiral (Citation2024) for a systematic review). Within the Australian Volunteers Program, climate change integration approaches were internally driven and inclusive of multiple perspectives, including program leaders, regional managers, country managers, volunteers, and external stakeholders. The research project provided senior management with an evidence base to feel confident that integrating climate change was an effective investment of resources. The reference group supported the program in navigating integration approaches that are effective and coherent to different organisational levels. The diverse voices represented in the interviews helped the program identify the priority areas of integration, existing approaches, and recommendations for future integration approaches.

5.1.3. Strategic and operational entry points

DFAT’s Climate Action Strategy, the Australian Government’s International Development Policy and the program’s Global Program Strategy provided a strategic framework and entry points for integrating climate change into the program. The program aimed to integrate climate change and considered entry points for integration at strategic and operational scales. The reference group and interviewees had diverse roles across the program, focusing on strategic and operational levels. This provided an opportunity to explore different plausible entry points of integration and recommend ways of integration at different levels.

5.1.4. In-built learning and capacity building

The Australian Volunteers Program’s integration approaches supported capacity building of staff members, volunteers, and partner organisations. The research process helped reference group members learn about climate change integration and understand how to operationalise integration activities in practical ways. This demonstrates how the contribution of this research to the practices of development organisations is significant and a benefit of collaborative action research. The in-country members of the reference group developed knowledge and capacity through the ongoing discussions in the reference group meetings, which paved ways for them to contribute beyond the research activity. For example, the country-level reference group members disseminated the research learnings to their teams and contributed to local-level capacity building in climate change integration.

Through the development of the volunteer guidance document, important climate change information can be shared from volunteers to local partner organisations. Since the program is a people-to-people initiative, the volunteers can disseminate the learning from the guidance to the local partner organisations and enable longer-term effectiveness through capacity building, which can help to reach the development goals of partner organisations.

5.1.5. Internal champion

The final enabler that supported the project’s success was having an internal champion to maintain momentum and coordination of activities. The internal champion worked to ensure a diverse group in both the reference group and as participants in the research, which supported effective integration at different scales and levels. The internal champion also prompted senior management to participate in the climate change integration conversation, which was important, as described in Enabler 2. As the main point of contact with UTS-ISF, the internal champion also helped coordinate research processes, activities, and meetings as needed.

5.2. Areas for future progress

The Australian Volunteers Program continues to focus on improving its approach to climate resilient development. Recognising that behavioural and organisational change takes time, effort, resources, and leadership (Ranger, Harvey, and Garbett-Shiels Citation2014), the program is considering ongoing incentives across multiple entry points to integrate a climate risk-informed approach.

The Climate Action Framework, developed by ACFID, provides a useful basis for considering different entry points for climate action. The framework links forms of climate action (adaptation, environmental restoration, and mitigation) to different levels of development organisations’ activities (operational, programmatic, and policy and advocacy) (ACFID Citation2021).

The framework makes clear the broad range and holistic approach required to fully integrate climate action and helps identify areas for further attention. For the Australian Volunteers Program and its managing contractor, AVI, at the operational level, this includes ongoing efforts to decarbonise programs and operations as set out in the organisation’s Environmental Sustainability Policy. Increasing energy efficiency and installing solar panels at AVI’s head office in Melbourne and other offices worldwide are long-term goals.

Programmatically, while recognising that international air travel will always form a core part of the program’s modality, the program aims to do more to promote remote volunteering and continues to explore ways to meaningfully and effectively support national volunteering infrastructure and “South to South” volunteering. This aligns with the program’s commitment to supporting locally led change and helping reduce the program’s carbon footprint.

At the policy level, the program is reviewing and updating its Global Program Strategy to give a sharper focus to gender equality, disability inclusion, and climate action. The Australian Volunteers Program ultimately has impact through the partners it supports, and so the new policy sets out the intent to increase the proportion of partners working in the climate action space that it supports through skilled volunteer assignments.

The three approaches described above have established the groundwork for these ongoing activities. The reference group provided an internal mechanism for discussing and driving forward the changes needed; the audit provided an evidence base for action; and the first “quick win” of the volunteer guidance gave momentum and internal legitimacy to extend the integration of climate change across the program.

6. Conclusion

While climate resilient development is commonly used across the development sector, implementing such an approach remains unknown for many non-climate-focused organisations. This paper has provided examples and outcomes of how a non-climate-focused program has taken steps to begin integrating climate change considerations in simple and effective ways. The Australian Volunteers Program drew on findings from a previous evaluation that recommended the program begin considering climate change, in line with DFAT policy. That evaluation provided the impetus for the program to take further action, which was driven by an internal champion and internal reference group with the support of senior management. Actions taken were easy to achieve and helped to build organisational momentum for further integration activities (in part through in-built capacity building and learning opportunities) and focused at both strategic and operational scales. The investments taken by the Australian Volunteers Program to integrate climate change also support good development practice and development outcomes. The program’s integration efforts, and the action research approach itself, therefore, set a good example for other non-climate-focused programs or organisations working in the humanitarian and development sector. The insights and lessons from the program and this research process can help other organisations identify entry points for integration and begin, continue, and/or strengthen their climate change integration actions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allum, C., P. Devereux, B. Lough, and R. Tiessen. 2020. Volunteering for Climate Action.

- Allum, C., P. Devereux, R. Tiessen, and B. Lough. 2022. IVCO 2022 Think Piece: Volunteering for Development and Responding to Climate Change.

- Australian Council for International Development (ACFID). 2021. Climate Action Framework for the Australian International Development Sector – Report. https://acfid.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ACFID-2021-Climate-Action-Framework_Report_V3_web.pdf.

- Australian Volunteers Program. 2021. Australian Volunteers Program Annual Report. www.australianvolunteers.com/assets/ALL_FILES/Resources/Australian-Volunteers-Program-Annual-Report-2020-21.pdf.

- Biagini, B., R. Bierbaum, M. Stults, S. Dobardzic, and S. M. McNeeley. 2014. “A Typology of Adaptation Actions: A Global Look at Climate Adaptation Actions Financed Through the Global Environment Facility.” Global Environmental Change 25:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.003.

- Brook, J. 2007. “International Volunteering Co-Operation: Climate Change. Discussion Paper.” International Forum on Development Service 16: 1–14.

- CoLAB Consulting. 2020. Documenting Australian Volunteers’ Contribution to Addressing Climate Change in the Pacific.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2019. DFAT Climate Action Strategy.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). 2023. Australia’s International Development Policy. Canberra.

- Davies, E., and B. Koff. 2021. Climate Action Framework for the Australian International Development Sector. Canberra: Australian Council for International Development.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade & Australian Volunteers Program. 2018. Australian Volunteers Program Global Program Strategy 2018-2022. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/australian-volunteers-program-global-program-strategy.pdf.

- Fee, A., P. Devereux, P. Everingham, C. Allum, and H. Perold. 2022. Longitudinal Study of Australian Volunteers (2019-22): Final Report (Summary). Prepared for the Australian Volunteers Program. https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/article/downloads/Longitudinal20Study20of20Australian20Volunteers20-20short2028April20202229.pdf.

- Forum. 2022. A New Dawn for Volunteering in Development: Research & Think Pieces Prepared for IVCO 2022. https://forum-ids.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Collected-Research-and-Think-Pieces-for-IVCO-2022.pdf.

- Fuso Nerini, F., B. Sovacool, N. Hughes, Laura Cozzi, Ellie Cosgrave, Mark Howells, Massimo Tavoni, Julia Tomei, Hisham Zerriffi, and Ben Milligan. 2019. “Connecting Climate Action with Other Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 2:674–680. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0334-y.

- George, T. 2024. “What is Action Research? | Definition & Examples.” Scribbr, January 12. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/.

- Gero, A., and T. Chowdhury. 2023. ACFID Climate Action Framework Analysis and Planning Part 2: Mitigation Case Studies. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, prepared for the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID).

- Gero, A., T. Chowdhury, and K. Winterford. 2022a. Integrating Climate Change Action Across the International Development Sector: Setting the Scene for ANGOs. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, prepared for the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID).

- Gero, A., T. Chowdhury, and K. Winterford. 2022b. Integrating Climate Change Action Across the International Development Sector: Enablers of Best Practice. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, prepared for the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID).

- Gero, A., T. Megaw, K. Winterford, and R. Cunningham. 2021. Deep Dive Evaluation of Climate Change, Disaster Resilience and Food Security in the Pacific: Final Report.

- Gupta, J., C. Termeer, J. Klostermann, S. Meijerink, M. van den Brink, P. Jong, S. Nooteboom, and E. Bergsma. 2010. “The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: A Method to Assess the Inherent Characteristics of Institutions to Enable the Adaptive Capacity of Society.” Environmental Science & Policy 13 (6): 459–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2010.05.006

- Hewitt, C., S. Mason, and D. Walland. 2012. “The Global Framework for Climate Services.” Nature Climate Change 2 (12): 831–832. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1745.

- IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Summary for Policymakers. www.ipcc.ch.

- Lawrence, J., F. Sullivan, A. Lash, G. Ide, C. Cameron, and L. McGlinchey. 2015. “Adapting to Changing Climate Risk by Local Government in New Zealand: Institutional Practice Barriers and Enablers.” Local Environment 20 (3): 298–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.839643

- Learmonth, B. 2020. Volunteering for Climate Action in Pacific Island Countries: Considerations for IVCO 2020. https://forum-ids.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Volunteering-for-Climate-Action-in-Pacific-Island-Countries.pdf.

- Lebel, L., L. Li, C. Krittasudthacheewa, M. Juntopas, T. Vijitpan, T. Uchiyama, and D. Krawanchid. 2012. Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation Into Development Planning. www.sei-international.org.

- Mulligan, B. 2010. “Climate Change: A Discussion Paper for the 2010 IVCO Conference. Discussion Paper. Melbourne.” International Forum for Volunteering in Development 18: 1–17.

- Opitz-Stapleton, S., R. Nadin, J. Kellett, M. Calderone, A. Quevedo, K. Peters, and L. Mayhew. 2019. Risk-Informed Development: From Crisis to Resilience.

- Pokrant, B. 2016. “Climate Change Adaptation and Development Planning: From Resilience to Transformation?” In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Anthropology, edited by H. Kopnina and E. Shoreman-Ouimet, 242–255. London UK: Routledge.

- Ranger, N., A. Harvey, and S. Garbett-Shiels. 2014. “Safeguarding Development Aid Against Climate Change: Evaluating Progress and Identifying Best Practice.” Development in Practice 24 (4): 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2014.911818.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury, eds. 2001. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. USA: Sage, Oregon Health & Science University.

- Runhaar, H., B. Wilk, Å Persson, C. Uittenbroek, and C. Wamsler. 2018. “Mainstreaming Climate Adaptation: Taking Stock About “What Works” from Empirical Research Worldwide.” Regional Environmental Change 18 (4): 1201–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5.

- UNFCCC. 2016. The Paris Agreement https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-.

- Yuriev, A., and O. Boiral. 2024. “Sustainability in the Boardroom: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 442: 141187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141187.