Abstract

There is an increasing trend towards people working post 65 years. This is due to a number of factors: social, economic, political and psychological. Very little work has been done looking at the health and safety aspects of those people working beyond State Pension Age. Although there is research on post-65–year-olds, this mainly centres on people in care homes, looking at their mobility and social needs. Because this work has not been done specifically on older people in the work setting, it is difficult to use the results in any meaningful way for workplace issues, especially relating to workplace health and safety. This article looks at the potential impact of increasing numbers in the post-65-year-old workforce. It examines what is known about ageing in this cohort and its effects on workplace performance and health and safety. It then looks at some novel ways in which technology can extend working life. Finally, it identifies gaps in the knowledge base relating to the emerging phenomenon of the post-65-year-old worker.

Background

Research suggests that ageing is a complex interaction of social, environmental and psychological factors on an individual’s chronological age, which will affect people differently (Ilmarinen, Citation2001). There is no commonly agreed definition as to when ‘old age’ begins as people age differently (Charness, Citation2008). Generally, people over the age of 50 years start to think of retirement and develop health issues, physical and/or cognitive, which may lead to them leaving the workforce. This may be a result of the ageing process itself, but it may also possibly be a socially induced artefact due to the arbitrariness of the former Default Retirement Age, which was 60 years for women and 65 years for men. In other words, the closer people got to retirement the more they felt the need/desire to retire. It was only 20 years ago that the trend was for people to retire early and it was not uncommon that people retired in their 50s, certainly for those who had a private or work pension. It was seen as an opportunity by organisations to downsize during a recession (Age UK, Citation2013; Vaitilingam, Citation2009). The lesson from that period was that making ‘older’ workers redundant led to skill loss and once recession fears had receded, the ensuing skill shortages made it difficult for organisations to bounce back quickly. In contrast, during the latest recession there has been a determined effort by employers to keep hold of their experienced, skilled workers.

Natural ageing

Ageing does not happen overnight and people do not just suddenly become old. It is an incremental process that affects people in differing ways. The decline in physiological functions may not be immediately apparent, as most people will not have to constantly test these functions to their limits. However, the safety margins between maximal function and critical threshold levels are eroded with age (Young, Citation1997). Generally, as people age, they start to become susceptible to illnesses that may make working more difficult. These include skin disease, mental health conditions, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis and other musculoskeletal diseases. We assume grey hair and wrinkles are the first signs of ageing, but some parts of the body are wearing out long before people look old. Most people reach their ‘peak’ functioning at around the age of 30 years. Natural ageing is incremental but affects everybody differently ().

Table 1. Some aspects of natural ageing.

Societal, psychological and health factors in ageing

The results of surveys on age reveal the perceptions and attitudes of those surveyed. They show that the majority of people believe the middle age starts at 55 and ends at 69, with one in five thinking that middle age does not begin until 60. Longitudinal studies have found that attitudes to ageing predict wellbeing in older age, with those who expressed negative attitudes towards old age, when young, experiencing a less satisfactory older age themselves (Moch & Eibach, Citation2011).

The ageing process itself, on any part of the body, can be initiated or speeded up by ill health and/or injury, poor diet, smoking, excess alcohol and the environment. Therefore, chronological age by itself is not a reliable indicator of how a person ages.

Why work past state pension age?

Once people get to the point when they can receive their state pension, why should they want to continue working? There are both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons that influence people’s decisions. These include:

Socio-legal

Employers are no longer able to compulsorily retire their employees and any employer who does so will have to follow a fair dismissal procedure based on the employee’s capability, declining competence, conduct, or some other substantial reason (UK Government, Citation2017). With no fixed retirement age, questions may arise as to the ability of older workers to perform effectively, especially in safety-critical jobs. For example, airline pilots already have to undergo testing on a regular basis, regardless of age (Flin, Citation2005). Should older workers have regular assessments linked to job-specific standards as part of their employment contract or would this be discriminatory?

The Statutory Pension Age (SPA) for both men and women is to increase to 66 years between 2018 and 2020 and then to 68 years between 2024 and 2046. This could change. In 1911, the first state pension was introduced at 70 years when life expectancy for men was approximately 74/75 years. The universal state pension for both men and women is only a recent phenomenon. It is likely that as healthy life expectancy continues to increase, pension age could rise beyond 70 years.

Economic

In the UK, 1.2 million pensioners have no income other than the state pension and other state benefits and around a third of workers between 40 and 60 are not in a current pension scheme. The number of people contributing to personal pensions fell from 7.6 million in 2007/08 to 6.4 million in 2008/09, with most workers aged 24 and under not having a pension plan. These statistics would be suggestive of the need for post-SPA working.

Social

Work provides people with social contact and status within the society, which people may not immediately want to give up at retirement age. Gradual retirement, which enables them to develop other interests and adjust to life outside of the workplace can provide the time for this adjustment. In some parts of industry there is a skill shortage, which could be overcome through the retention or re-employment of post-SPA workers. Society may also come to expect that those post-SPA should continue to contribute to it through work.

Psychological

For most people, intelligence remains stable until the age of 80. In addition, older workers often have accumulated experience and/or learned compensating strategies. Dementia is not generally evident in people at 65 years, but one in three people will go on to develop dementia over the age of 80. Evidence points to activity, social interaction and intellectual stimulation, as promoting cognitive functions, all of which can be found in the workplace to a greater or lesser extent (Hu, Lei, Smith, & Zhao, Citation2012). This would suggest that post-SPA working is beneficial.

Health

Almost 50% of the workforce has left employment by the age of 65 years owing to ill health or disability. Those who remain in the workforce at that age are generally those who are healthy and not limited through illness or disability.

There appears to be no evidence to sustain the myths that working longer leads to a shorter life span; the opposite appears to be the case. Studies investigating retirement age and mortality showed that early retirement was not associated with longer life than retirement at age 65 (Tsai, Wendt, Donnelly, de Jong, & Ahmed, Citation2005). It appears that people who retired at 55 had a significantly higher mortality rate by age 65 than those who stayed at work. Some see the ageing process as a ‘disease’, which is curable and are working towards a ‘cure’ (Sethe & de Magalhaes, Citation2013).

Some characteristics of post 65 workers

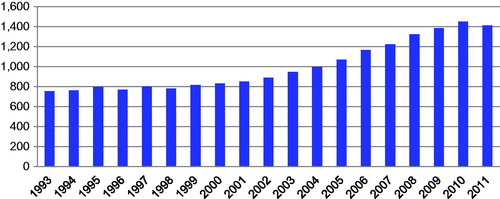

Approximately 12% of the workforce are over SPA and this is increasing ().

Around two-thirds are part-time.

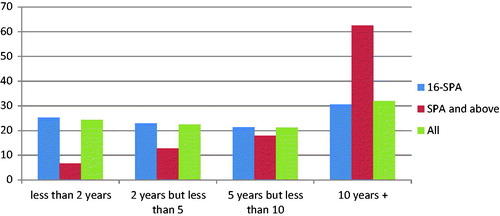

Eighty per cent have been with their employer for at least five years ().

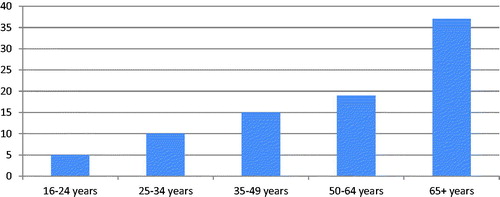

Thirty-seven per cent are self-employed ().

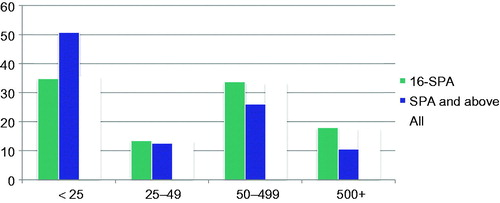

In 2011, 51% were in organizations with a workplace size of 1–24 employees ().

There are more women (61%) in the workforce post-SPA as compared to men (39%).

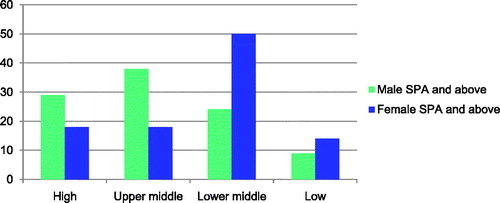

Men tend to stay on in higher status roles: Women stay on in lower status employment ( and ).

Accidents and illness tend to be more of an issue for those working in lower status jobs ().

Three-quarters of those under 55 are in full-time employment, this falls to under half of those in the 55–64 group.

Table 2. Top five jobs for men and women post-SPA.

Human performance enhancement

Human performance enhancement is a technique that can be used for increasing human capability and capacity either physically or cognitively. It comprises a range of technologies, mainly therapeutic in origin but increasingly used to enhance capabilities for all. An ageing population, however, can use some of these technologies to counteract some of the problems ageing brings.

The increasing availability of Human Performance Enhancers such as drugs, exoskeletons, replacement limbs and brain implants has the potential to extend working life and capacity, but little is known of their effects on performance in the workplace, and with drugs their effect on the individual of long-term usage.

Some of these technologies may appear futuristic but they are all either in development or at early usage stage.

Bionic limbs

Bionic limbs were designed for people who had lost limbs through accident or illness and not specifically as enhancements for older people. However, as the technology increases so does the opportunity for those with bionic limbs to return to the workplace, and remain in the work situation for as long as they feel capable, possibly having modifications made to their limbs as the technology advances. This scenario potentially offers a long extended working life. Current research has been able to design prostheses that can give the user a sense of touch, temperature, pressure and vibration. It is unlikely, however, that these will become readily available before the end of this decade.

Exoskeletons

It is estimated that as many as 44 million workers in the European Union are affected by work-place related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), representing a total annual cost of more than 240 billion Euros. The Exoskeleton is one technology designed to enhance workplace performance and to help in overcoming some of the issues of an ageing workforce. Although designed with an ageing workforce in mind, the exoskeleton can also be utilised by younger healthy workers to enhance performance. Although there are a number of exoskeletons in development, mainly for military use, two have been designed for work-related usage: Hybrid Assistive Limb, HAL- 5 (Cyberdyne, Citation2010) and Robo-Mate (Robo-Mate, Citation2013).

Electronic implants

Electronic implants (brain, sensory and subcutaneous) are used for relieving pain, enhancing sight, and hearing and regulating drug regimes. As part of the natural ageing process, older people will become more susceptible to decrements in eyesight and hearing as well as possible pain due to conditions such as arthritis. The use of electronic implants should enable them to continue in the workforce.

Organ replacement

The most common causes of disability and death are diseases of the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys and pancreas, many of which are potentially treated by organ transplantation. The possibility of organ dysfunction and failure will grow over time as part of natural ageing. This is already putting a strain on traditional techniques, e.g. organ donation. Continuing research in organ transplantation using synthetic and non-human organs is now promising more availability for transplants, enabling those receiving them to extend active life.

Drugs

We know that non-prescription drugs are used in the workplace especially in high pressure jobs, e.g. the media, law. When used by individual workers there is likely to be no harm to anyone other than the individual. They are readily obtainable over the internet or elsewhere. Drugs such as Modafinil will allow people to remain awake for 48 h. Ritalin is used for cognitive enhancement, e.g. memory. Very little is known about performance enhancement drug usage over the long term. Proper controlled research is sparse and therefore side effects and possible dangers from long-term use are not yet known.

To what extent older people would use these types of performance enhancers is unclear but new drugs are being developed all the time with different properties. Prescription drugs, e.g. ibuprofen, are used by many to reduce pain and discomfort, and for mood control there are sedatives and tranquilisers. Using these types of drugs may lead to complications, especially if more than one drug is used. Both employees and employers need to be aware of such possible drug interactions (BNF British National Formulary – NICE, Citation2017).

What we don’t know

The post 65-year-old workforce is increasing in size, but little is known of the effects of working past 65 years on both the individual’s health and their ability to work safely. What research has been done, mainly laboratory based, suggests that older workers’ reaction times deteriorate and physical strength is reduced. However, cognitive abilities do not decline and older workers tend to have fewer ‘one-day’ absences than their younger counterparts. The limited evidence base means that what is known of the older worker has usually been extrapolated from studies involving older people in home or care home settings, not employment settings. This means that information regarding the extent to which this older workforce can participate in employment, safely and without incurring a significant health decrement, has yet to be determined.

Summary

Biological age does not necessarily reflect chronological age and there is no evidence that older workers are more likely to have their health adversely affected by work than younger workers. Neither is there evidence to suggest that older workers’ cognitive or physical functioning affects health and safety or workplace performance. Some studies show that older workers are more dedicated to the workplace, have fewer sickness absences and stay in jobs longer. The relationship between age and productivity is much more complex, due to the benefits of on-the-job experience, increased job knowledge, professional mastery, expertise, adaptability and the use of compensatory strategies. The skills, experience and maturity of older workers generally outweigh potential problems such as increasing age-related ill health.

There is no evidence that working post retirement shortens life-span (Bamia, Trichopoulou, & Trichopoulos, Citation2008).

There is no consistent evidence that older workers are generally less productive than younger workers (Department of Work and Pensions [DWP], Citation2017).

There is accumulating evidence that job experience is a more valid and reliable predictor of productivity than chronological age (Yeomans, Citation2011).

Sick leave of one day or more decreases with age whereas sick leave of one month or more increases with age.

Workplace accidents involving older workers tend to result in more serious injuries.

Older workers are generally less likely to have accidents than their younger counterparts (Okunribido & Wynn, Citation2010).

Conclusions

We know that the age profile of the workforce will reduce the relative labour supply significantly over the coming decades and changes in pension age will further skew the distribution towards older workers. Employers will need to be mindful not only of the strengths of the older workers but of their weaknesses as well, e.g. slower reaction times. One way to help reduce the impact of this will be to fully utilise the skills and experience of older workers. They are in a unique position to pass on skills and knowledge to younger workers especially on workplace health and safety culture. Although we know that reaction/response times slow with age, in the workplace older workers compensate for this through their experience by ‘anticipating’ events and thus preventing incidents from occurring.

Research indicates that there is no reason why older people cannot function competitively in the workplace. Better healthcare and technology are already enabling more olderpeople to extend their working life but health and safety research on the post-SPA employee remains very limited. However, the first challenge to industry should be to enable employees to work within a safe and healthy environment from the outset of their working lives and enable them to remain in the workforce until they choose to leave.

Research strongly suggests that older people in the workforce can be considered both reliable and capable but industry needs to know what the health and safety implications of this post-SPA cohort are.

Disclaimer

This publication and the work it describes were funded by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect HSE policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Snodgrass

Richard Snodgrass was an occupational psychologist at the time of writing, working in the Health and Safety Executive’s Foresight Centre. He is now retired.

References

- Age UK. (2013). Older workers at high redundancy risk. Retrieved from https://www.ageuk.org.uk/latest-press/archive/older-workers-at-high-redundancy-risk/

- Bamia, C., Trichopoulou, A., & Trichopoulos, D. (2008). Age at retirement and mortality in a general population sample. The Greek EPIC Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167, 561–569. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm337

- BNF British National Formulary – NICE. (2017). Retrieved from https://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- Charness, N. (2008). Aging and human performance human factors. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 50, 548–555. doi:10.1518/001872008X312161

- Cyberdyne. (2010). “What's “HAL” (Hybrid Assistive Limb®)? Retrieved from www.cyberdyne.jp/english/robotsuithal/index.html

- Department of Work and Pensions. (2017). Older workers and the workplace (Research Report No. 939). Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/584727/older-workers-and-the-workplace.pdf

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Human ageing. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1354293/human-aging

- Flin, R. (2005). Safe in their hands? Licensing and competence assurance for safety-critical roles in high risk industries. Report for the UK Department of Health, October 2005.

- Hu, Y., Lei, X., Smith, J.P., & Zhao, Y. (2012). Effects of social activities on cognitive functions. Evidence from CHARLS. WR-918 RAND Labor and Population working paper series. Retrieved from https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1993328

- Ilmarinen, J.E. (2001). Aging workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58, 546–552. doi:10.1136/oem.58.8.546

- Moch, S.E., & Eibach, R.B. (2011). Aging attitudes moderate the effect of subjective age on psychological well-being: evidence from a 10-Year longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging, 26, 979–986. doi:10.1037/a0023877

- Okunribido, O., & Wynn, T. (2010). Ageing and work-related musculoskeletal disorders A review of the recent literature. HSE Research Report RR799. Retrieved from http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr799.pdf

- Robo-Mate. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.robo-mate.eu/

- Sethe, S., & de Magalhaes, J.P. (2013). Ethical perspectives in biogerontology. In M. Schermer & W. Pinxten (Eds.), Ethics, health policy and (anti-) aging: mixed blessings (pp. 173–188). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Tsai, S.P., Wendt, J.K., Donnelly, R.P., de Jong, G., & Ahmed, F.S. (2005). Age at retirement and long term survival of an industrial population: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal (BMJ), 331, 99. doi:10.1136/bmj.38586.448704.E0

- UK Government. (2017). Working after state pension age. Retrieved from www.gov.uk/retirement-age

- Vaitilingam, R. (2009). Recession Britain: findings from economic and social research. Retrieved from www.esrc.ac.uk/files/news-events-and-publications/publications/…/recovery-britain/

- Yeomans, L. (2011). An update of the literature on age and employment. HSE Research Report RR832. Retrieved from www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr832.pdf

- Young, A. (1997). Ageing and physiological functions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 352, 1837–1843. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0169