ABSTRACT

Based on statistical analysis of the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) international student data from 1998 to 2014, we provide the first detailed analysis of UK international doctoral student data (and the gaps therein). We highlight missing and ambiguous data and develop the profiles of these students, with a particular focus on gender, discipline, destination university, source of funding and country of origin. We argue that the current marketized system of international higher education coupled with a national focus on equality has largely limited the social composition of international doctoral students to those who are: academically capable; and either financially able to pay international tuition fees and subsistence in the UK (for them and their families) or capable of securing overseas funding, primarily from national governments. We conclude by reflecting on the implications of this for the internationalisation of research and knowledge production.

1. Introduction

The internationalisation of research and knowledge production has become a central issue in higher education (HE) studies (Woldegiyorgis et al., Citation2018). Scholars emphasise the instrumental benefits to research that viewpoint diversity carries and more recently, ethical considerations about viewpoint diversity inclusion have come to the fore (Bolsmann & Miller, Citation2008). However, instrumental, and ethical arguments are not often the rationales associated with international student recruitment. Rather, scholars suggest that international students are plagued by ambiguous rationales and representations, and international students have been widely portrayed as income generators; elites; ambassadors/instruments of soft power; academic tools; and alternatively, as ‘bogus’ students (e.g. unqualified) that should be expelled from the country or as ‘bona fide best and brightest.’ (Bamberger, Citation2022; Lomer, Citation2017; Stein & de Andreotti, Citation2016).

In this paper we explore the implications of the framing of the desirable international student as not only the ‘Best and Brightest’, but also one that can afford international tuition and subsistence – or access such assistance from overseas funding bodies – on the diversity of knowledge producers in universities. Our initial contention is that these portrayals, embedded in a marketized system of HE, will result in limited social diversity in the international doctoral student body. Our empirical entry point is UK higher education. The UK attracts large numbers of international students. It is the second largest host country behind the US with close to 20% of its student body hailing from overseas and over 40% of its doctoral students (OECD, Citation2020). While the UK has always hosted international students, the growth of these numbers over the past two decades has been attributed to a series of robust branding campaigns and targeted policies at the national level (Lomer, Citation2017; Lomer, Papatsiba & Naidoo, Citation2018); and aggressive international student recruitment strategies at the institutional level (Bolsmann & Miller, Citation2008; Findlay et al., Citation2017). Exacerbating this issue, many scholarships and funding schemes are nationally based and exclude international students, emphasising the national framing of issues of social justice and ‘othering’ of international students, while also supporting national agendas/elite social hierarchies of countries who provide support to their students to study abroad. We analyse the diversity of international doctoral students in the UK and the possible implications of this (lack of) diversity for representation and plurality of knowledge creation.

This paper focuses on international doctoral students for three reasons: one, they are students who have a research remit, and thus lying at the nexus of students and researchers, they play an important role in internationalising research, supporting the integration of diverse epistemologies in current and future knowledge production; two, they comprise the future face of knowledge producers in the academy and beyond; and three, despite the large numbers of international students at the doctoral level, much of the academic literature either focuses on international students at the undergraduate and postgraduate taught levels or focuses on academic staff, -rather less research has investigated the role of international doctoral students and their connection with diversity, internationalisation of knowledge production and global HE.

Based on an interpretative descriptive statistical analysis (Babones, Citation2016; Gorard, Citation2006) of HESA international student data from 1998 to 2014, we provide the first detailed analysis of UK international doctoral student data (and the gaps therein); we develop the profiles of international doctoral students in the UK, with a particular focus on gender, discipline, destination university, and country of origin. We explore and problematise the statistical information unavailable and discuss the implications of this for higher education, knowledge production and social justice more widely, with a particular interest in how the social composition of international doctoral students intersects with conversations about the ethical and instrumental aspects of internationalisation of knowledge of the university more broadly.

We begin by analysing the instrumental and ethical arguments for diversity in knowledge production, linking this to internationalisation in research and the role of international doctoral students in knowledge production. We note the high percentage of the world’s doctoral students who are globally mobile, and the ambiguous effects of internationalisation on diversity in knowledge production, due to neoliberal/commercialised HE systems and national framing of education equality. We establish the widespread portrayals of international students in the UK literature (e.g. elites; goodwill ambassadors; ‘Best and Brightest’). We then analyse the statistical data (and gaps therein) on UK international doctoral students in relation to these literatures, revealing the classed and gendered nature of the current HE system in the UK. We conclude by developing the implications for diversity in knowledge production more broadly.

2.1 Diversity in knowledge production, internationalisation and the national lens

Diversity in research and knowledge production can be defined in numerous ways (e.g. disciplinary knowledge; methodological diversity; ethnicity; gender; race) (Maker, Citation2020; Neumann, Citation2002) and there has been a growing movement towards an understanding that such diversity is integral to ‘good’ science. Two main arguments for diversity in knowledge production have emerged in recent years: instrumental and ethical. These are often overlapping and mutually inclusive. The instrumental argument claims that science is served by viewpoint diversity (e.g. Longino, Citation1990; Pöyhönen, Citation2017) and thus, in striving for better solutions to complex problems, diversity should be integrated into research teams. This perspective echoes the ‘business rationale’ for diversity in which businesses aim to manage difference in their organisations, in order to reap a competitive advantage (Zanoni & Janssens, Citation2004; Zanoni et al., Citation2010). This argument is often behind international research collaborations, and considerable research has focused on the (largely positive) outcomes of diverse cross-national research collaborations (e.g. Kwiek, Citation2015; McManus et al., Citation2020; Sun, Citation2020). In addition, other authors highlight the importance of cognitive diversity (Pöyhönen, Citation2017). Intemann’s (Citation2009) analysis of diversity in science practices in the United States concluded that, diversity is important for the workforce, and facilitates increased objectivity and social justice.

The ethical argument is that all people should have the opportunity to contribute to knowledge production, no matter their individual characteristics, and that this is an issue of social mobility and equality in a just society (e.g. Bernal & Villalpando, Citation2002; Montoya & Valdes, Citation2008). This argument is often behind access/widening participation/affirmative action schemes across student and academic staff recruitment policies (e.g. Arday, Citation2020; Bhopal et al., Citation2016). However, these schemes are placed within national containers, and are not extended outwards, and thus ethical arguments for diversity in science, are often limited to the boundaries of the nation-state, despite recognition of the increasingly global nature of science.

Internationalisation, one of the most prominent policies and features of contemporary higher education, would presumably be a boon for diversity in knowledge production, with large numbers of the world’s doctoral cohort studying internationally (OECD, Citation2020). However, despite internationalisation’s association with global citizenship, humanitarianism and cosmopolitanism (Bamberger et al., Citation2019; George et al. Citation2018), internationalisation – and particularly international student mobility – is linked to building elites and increasing stratification (Brooks & Waters, Citation2011); environmental issues (Shields, Citation2019); racism (Brown & Jones, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2017); and increasingly scholars note that diversity is not always achieved or that the diversity of international students and staff from the Global South is often marginalized (e.g. Stockfelt, Citation2018). Indeed, the field of critical diversity studies aims to examine the rise of and uncontested good of ‘diversity;’ scholars in this tradition link diversity to an agenda of managing difference and argue that this has the effect of obscuring unequal power relations (Zanoni et al., Citation2010). Thus, it cannot be assumed that the increased numbers of doctoral students studying internationally, has necessarily brought about a significant increase in diversity in knowledge production. This has been chalked up to two main issues: first, the neoliberal version of internationalisation practiced in many countries, shifts the focus of international students towards economic contributions, and is based in the logics of competition, market supremacy, and rational decision-making, with little recognition of structural issues of inequality (Bamberger et al., Citation2019; Stein et al., Citation2016). Second, social equality – and the role of HE and science therein – is framed within national containers. This results in a situation in which neoliberal internationalisation espouses commitment to the cognitive diversity ostensibly offered through ISM and internationalisation of the curriculum, but often lacks structural support on the national and institutional levels (e.g. international student access/participation plans, scholarships and funding; contextual/holistic admissions).

Internationalisation, despite its positive connotations, is primarily viewed in the academic literature as an expression of neoliberalism (e.g. Bamberger et al., Citation2019; Stein et al., Citation2016). This stems from the marketisation of HE systems in many countries, which encourages competition between institutions for resources (e.g. students). Such a system views HE as an increasingly private good, with benefits that accrue primarily to individuals – and thus justifies shifting the cost of HE to individuals. This has resulted in shrinking government funding for (home) students on the one hand with freedom to set tuition fees for international students on the other. Thus, many universities have come to rely on international students as a source of income, creating and perpetuating views of international students as ‘cash cows’ and ‘clients’ in many higher education systems, particularly the US, Australia and UK (Robertson, Citation2011; De Vita & Case, Citation2003). The focus then on international (doctoral) students as economic contributors rather than as contributors to knowledge, is particularly inappropriate for several reasons. First, it downplays other contributions that doctoral students offer; doctoral students are engaged in research, and as such, contribute to public goods. Thus, their studies should not be considered primarily as individual (private) goods. Second, it perpetuates a view of international students as affluent, with the economic resources to study internationally, and thus not in need of support; however, doctoral students are typically older than other students, and unlikely to have financial support from their parents. At this stage in their lives, they are also more likely to have caring and family responsibilities that require even greater support.

Despite research which argues for the global public good role of higher education (Marginson, Citation2011), and decolonial scholars who call for multipolarity and a global society beyond national containers (Mignolo, Citation2018), to a great extent, the economic and social contribution of higher education are seen through a national prism. Relatedly most of the higher education literature examines the outreach, access, inclusion and equity initiatives in higher education through national lenses – ‘methodological nationalism’ which Shahjahan and Kezar (Citation2013) argue contributes to narrow national definitions of the social challenges that might have a global origin and impact. Thus, the higher education sector is seen as contributing primarily to national development and aims – increasingly within a global competitive arena – despite the growing numbers of international students. Thus, it is not that access, widening participation, affirmative action, etc. schemes do not exist, it is that as they are currently framed, they are national endeavours that are limited to concerns for national social equality and justice.

2.2 Internationalisation and the dominant economic representation of international students in the UK

As indicated previously, the UK is one of the main destinations for international students, with particularly large numbers of international doctoral students (OECD, Citation2020). In the UK HE system, all students are required to pay tuition fees, however, international non-EU students are charged a rate significantly higher than those of UK or EU citizens. They are also subject to different rights and responsibilities (Tannock, Citation2018) including post-study work opportunities, student visa application fees, medical surcharges and intensive monitoring (Mateos-Gonzalez, Citation2019). These measures indicate that an economic agenda is the dominant driver of international student recruitment to British universities, rather than the pursuit of knowledge and diversity. The UK has invested significant efforts in recruiting international students, and as indicated previously, the explosive growth in international student numbers over the past two decades has been attributed to a series of robust branding campaigns and targeted policies at the national level (Lomer, Citation2017; Lomer, Papatsiba & Naidoo, Citation2018); and aggressive international student recruitment strategies at the institutional level (Bolsmann & Miller, Citation2008). Research indicates that international students in UK policies are plagued by ambiguous rationales and representations, and international students have been widely portrayed as economic resources; national elites; good will ambassadors; academic tools; and as ‘bogus’ students (e.g. disingenuous, unqualified) that should be expelled from the country or as ‘bona fide’/‘best and brightest’ (e.g. Lomer, Citation2017; Robertson, Citation2011). In light of the coronavirus pandemic, discourses on the role of international students as income generators and the fears of missed income from the universities resurfaced in the British media with major outlets as BBC publishing articles titled ‘Coronavirus: Universities fear fall in lucrative overseas students’ (Bloom, Citation2020). Further news articles appeared on the loss of income for local economies in university towns from the absence of national/international students and tourists (Davies, Citation2020); rarely the media discusses the impact of coronavirus on international student’s mental health or interruptions to their studies. Only recently reports began to appear on the hardships caused by the pandemic to the daily lives of some international students who rely on food banks (Popp, Citation2021). Indeed, such representation of international students and the over-emphasis on the economic aspect of student mobility is consistent with representations of all (not exclusively doctoral) students in the UK (Lomer, Citation2017).

In the most recent policy paper on international education strategy in the UK, explicitly titled ‘International Education Strategy: Citation2021 update: Supporting recovery, driving growth’ the economic role of transnational education (TNE) is reiterated:

“At the heart of this update, we are reaffirming our commitment to the ambitions of the 2019 strategy to increase the value of our education exports to £35 billion per year and the number of international students hosted in the UK to at least 600,000 per year. We reaffirm our ambition to achieve both by 2030. This update will set out how the government will support the sector’s journey from recovery to sustainable growth” (Education strategy, Citation2021).

While the 2021 education strategy highlights the importance of global partnerships in higher education and the availability of scholarships to study in the UK, such as Chevening, Marshall, and the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission, students are viewed through their countries, most of which are portrayed through economic/political lenses. Most of the regions are described in terms of the market opportunities – Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, whilst Indo Pacific region is specifically described as ‘high-potential market’ (Education strategy, Citation2021). Furthermore, international student employability upon graduation in the UK is conceptualised based on the ‘UK’s skills needs’ rather than the preferences of the students themselves (Education strategy, Citation2021). Thus, based on the newest higher education strategy in the UK, prevailing trends of representing students as contributors to national political and economic aims, are not envisioned to deviate in the near future.

The overall structure of the UK higher education sector and internationalisation is viewed as neoliberal in nature, and the form of national programs to promote gender inclusion and Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) access, such as Athena SWAN, Race Equality and Access and Participation Plan have borrowed from neoliberal ideas of ‘diversity’ (Kim & Ng, Citation2019). These programs face criticism for not facilitating deep inclusion (Bhopal & Pitkin, Citation2020), and difficulties of transitioning from doctoral studies to an academic career persist for the BAME population (Arday, Citation2020). They likewise have been critiqued for reflecting the ‘managing diversity’ approach as opposed to working towards structural and systemic equality. Higher education’s contribution to the economy and culture is primarily seen through the lens of national interest, and thus, these diversity initiatives on undergraduate and graduate levels, are limited to the national domain (i.e. citizens). Thus, while the new financial support plan to higher education includes international students impacted by Covid-19 (Gov UK, Citation2021), apart from the specific funding schemes and institutional grants, most of the inclusion initiatives in UK higher education do not extend to international students. While the topic of internationalisation of higher education is one of the most researched areas in the field of higher education studies, and knowledge production has become one of the most important agenda items in the ‘global knowledge economy’ it is particularly notable that compared to the existing number of studies on internationalisation of curriculum and international student mobility (at the undergraduate and post-graduate levels), with few notable exceptions (e.g. Sato & Hodge, Citation2009; Wang & Li, Citation2011), rather less research investigates international doctoral students.

3. Methods

This study focuses on the following guiding research questions:

1. Who are international doctoral students in the UK? What do we (not) know about them?

2.What are the implications of the international doctoral student profiles (and missing data) for creating a global tapestry of knowledge production and advancing more diverse forms of internationalisation?

To address these foci, we adopt an interpretive quantitative approach (Babones, Citation2016; Gorard, Citation2006). We adopted this approach to address the unobservable patterns and processes that underlie observed data in an attempt to deliver more understandable and meaningful results than could be reached using conventional positivist approaches. In order to address the research questions, we relied on analysing the dataset: ‘Students in Higher Education Providers 1998/1999-2015/16ʹ licensed by Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). The dataset contains information on international (non-UK and non-EU) doctoral students, who were pursuing advanced degrees (doctoral) at universities in the UK from 1998 until 2014. HESA collects data on the student populations from the three types of HE providers throughout the UK annually from 1994/95: Higher education (HE) providers in England registered with the Office for Students (OfS) in the Approved (fee cap) or Approved categories; publicly funded HE providers in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; and further education (FE) colleges in Wales.

The access to data requires a substantial fee, although it comes with a 75% discount for students, our access to this data cost over £2000. Given the richness of the data, their scope and importance for systematic research, as well as the fact that information on domestic students of similar standard and breadth is available free of charge, raises questions about the purpose of such an obstacle and more importantly about open and equal access provision.

Due to limitations in the coding used by HESA, we are unable to precisely tell how many students have switched to another educational provider or to track them after they became ‘dormant’ (presumably, dropped out). HESA supplied data without the personal identification code per student, thus, we were unable to track the educational history of an individual student (e.g. we do not know if a particular student from China began her studies in Oxford, then transferred to UCL and finished her degree there or how this particular student was funded and where she lived). This coding issue triggers large volumes of missing data in the ‘continuation status’ marker variable with 99% percent of missing data. The second largest volume of missing values is found in the socio-economic classification with 80% of the observations missing (in part because this only began to be collected by HESA in 2002/2003 onwards). This does put certain limitations on the data analysis. For example, we cannot follow individual students’ educational trajectory; identify how individual students are funded, etc.

The empirical analysis focuses on addressing and identifying key features and characteristics of the population of international doctoral students in UK HE by performing a longitudinal analysis of patterns in the data across the 16-year period. We define doctoral students through two variables drawn from HESA dataset: Doctorate (research) and Doctorate (taught). We look at social and economic characteristics of international doctoral students: citizenship, gender, sources of funding, age, disciplines, and choice of universities. We had originally hoped to analyse many more variables including ethnicity; race; socio-economic status; marital status; disclosed disability; and caring responsibilities. However, these indicators were either unavailable, or were so incomplete as to render an analysis useless. While these additional indicators would have provided considerable nuance to our arguments, our analysis still provides significant insights into the cohort. The implications of this e-missing data will be revisited in the conclusion.

The variables were analysed in many different combinations; we do not present all of these findings, rather, in the following we analyse a selection of the most relevant findings relating to the international doctoral student population. We analysed the entire data set from 1998–2015, and we draw attention to changes and trends over time, however, the majority of tables and figures (unless otherwise noted) are aggregate figures.

4. Findings: descriptive analysis of international doctoral students in the UK

The UK has attracted 489,583 overseas (non-UK and non-EU) doctoral students (both taught and research) to its universities from 1998/1999 till 2015/2016. The data show that nearly 60% of the cohort are categorized as male (293,597) – as based on an analysis of the ‘sex’ variable. We note a shift over time in this variable, which reflects fluctuating social norms. Prior to 2012/13, HESA used the category of (biological) ‘sex’ as an indicator of gender, which was a binary option until 2007 at which point the ‘other’ category was added for students ‘whose sex aligns with terms such as intersex, androgyne, intergender, ambigender, gender fluid, polygender and gender queer’ (HESAFootnote1). Only 22 students reported ‘other gender’ from 2007 till 2014. This relates to a shift in social categories, and the rise of the transgender social movement (Ridinger, Citation2014). The proportion of women grew slowly over the years from 32% in 1998 to 43% in 2015, however there is still a clear imbalance.

As indicates, the largest sending countries of non-UK/EU doctoral students are China (63,579) and the USA (43,017) followed by Malaysia, India and Saudi Arabia with each sending more than 20,000 students over the 16-year period. Canada, Nigeria, Thailand and Taiwan are in the middle of the table with 17,696, 16,797, 14,847 and 13,378 respectively. Pakistan rounds out the top 10 countries with 12,881 students attending doctoral programmes in the UK from 1998 until 2014. Similar to the gender/sex ambiguities, HESA has categories for country of domicile and nationality. Our analysis is based on the country of ‘permanent residence/domicile’ variable which is defined as ‘ … the place where a student normally lived for non-educational purposes before starting their course … ’.Footnote2 The nationality variable is defined by HESA as the ‘country of legal nationality’ of the student and this was an optional field until 2007 and still is for educational providers in Northern Ireland.Footnote3 This appears to reflect a growing awareness of HESA that nationality may not indicate residence and that a place of birth, does not necessarily guarantee citizenship. However, the ‘nationality’ variable has still been unable to present a comprehensive picture of students’ citizenships and origins; only one entry is allowed which does not account for students with dual nationalities. HESA guides that ‘Where a student has dual nationality including British, they should be coded as United Kingdom (GB). If a dual nationality, not including British, but including non-UK EU country then use relevant EU country code. If neither British or non-UK EU country then code as either nationality.’Footnote4 This reflects the purpose of the HESA statistics: a tool to establish a tuition fee range, not a diversity measure.

Table 1. Top country of origin of international doctoral students studying in the UK by doctoral degree type (research and taught).

In contrast to the research programmes, which are the preferred option by the vast majority of international students, taught doctoral programmes, which HESA classifies as ‘Doctorate degree that does not meet the criteria for a research-based higher degree’, appear to be of significantly less interest among international students. While this trend remained consistent until 2012, when more overseas students started to enrol into taught doctoral programmes, the overall international student population in taught doctoral programmes remained extremely small (0.54% of the entire cohort) with the largest countries of origin being India (374 students) and the USA (212 students). This small number of taught doctoral degrees may be because of the different levels of status and recognition of taught doctoral programmes internationally (e.g. not all national licensing systems recognise professional doctoral degrees, particularly those from abroad, while the PhD is more readily exportable, see Bamberger, Citation2018). The geographical distribution of students across research and taught students remains more or less the same, but China being the largest country of origin of doctoral students in the UK, its students are choosing to predominantly pursue research degrees rather than taught doctorates. Notably, this confirms that the vast majority of international doctoral students in the UK, are indeed engaged in research.

The choice of universities of research and taught students follow specific patterns; research students tend to enrol at research-intensive Russell Group institutions, the most popular being University of Oxford (34,133), University of Cambridge (34,005), University of Manchester (17,985), University of Nottingham (16,868), and University of Leeds (13,841), whereas the top recruiters of taught international doctoral students hail from the lower-ranked, post-1992 universities: University of Buckingham (510 students), University of East London (219), Heriot-Watt University (203), Nottingham Trent University (110). This pattern broadly holds across country of domicile and gender. Thus, it appears, that international doctoral students in research programmes – no matter their gender or country of origin – choose higher ranked institutions, while those in taught programmes choose lower ranked and post-1992 institutions.

In contrast, the choice of subject differs along lines of country of origin and gender. As relates to subject, the data indicate that the top three subjects among US students are Historical & Philosophical Studies (11,485 students), Social Studies (6,296) and Languages (5,198). Chinese students are most concentrated in Engineering & Technology (22,203), followed by Physical Sciences (7,388) and Business & Administrative Studies (5,953). Malaysian students (third largest country of origin) show a similar pattern to the Chinese: Engineering & Technology (9,222), Business & Administrative Studies (2,426) and Biological Sciences (2,098). This trend dovetails with contemporary research that indicates that Chinese and other Asian students are more oriented towards STEM subjects. For example, Ma’s (Citation2020) study on Chinese students (although at the undergraduate level), indicates that students are under considerable pressure to pursue practical degrees – viewed as aligned with STEM – that will lead to secure and lucrative employment.

Gender is likewise linked to subject choice; as indicates, men appear to study STEM subjects (e.g. engineering and technology, physical sciences, computer science) while women are more evenly distributed among subjects, showing similar favour to Social studies and engineering and technology; however with a much higher representation in the fields of Education and Languages.

Table 2. Choice of subjects by male and female international doctoral students in the UK (cumulative) .

There is very little research available on the ways international students fund their education in the UK. In part this may be due to the existing perception of international students as elites and ‘cash cows’ who bring financial resources to host countries/institutions (De Vita & Case, Citation2003; Leyland, Citation2011). It may also indicate a lack of concern with providing maintenance grants and scholarships because international students are portrayed as not only ‘best and brightest’ but also those able to financially afford an international education.

HESA has one variable related to funding: ‘Tuition fees.’ This variable indicates ‘the major source of tuition fees for the student where this is known. This includes fees from UK government, research councils, EU sources and other sources. The predominant source is selected where there is more than one source of award or financial backing.’ This means that HESA only records one source of funding, specifically for tuition fees. There may be multiple sources of funding for myriad purposes, including those which cover living and research expenses, however, HESA does not record this. We likewise cannot know whether tuition fees are covered in full or in part, thus, we cannot estimate how significant the assistance from one source was or whether the student used a combination of different funding sources to cover tuition fees and maintenance.

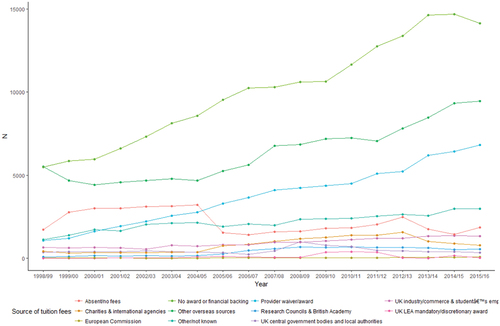

The largest segment of international doctoral students in the UK are self-funded and have no award or financial backing for tuition fees (36.8%), a trend which has been increasing over the years. The second largest segment of students (23.3%) receive funding from ‘other overseas providers’, which include overseas governments and organisations, and non-UK based multinational organisations. Finally, the third most popular source of funding are tuition fee waivers or scholarships from the host institution (13.7%), which shows an upward trend over time, indicating that universities are slowly providing more assistance to international doctoral students. The difference from year to year of these top three sources of funding are presented in the below.

As demonstrates, the patterns of sources of tuition fees for international doctoral students in the UK throughout the years, indicates that while the number of students with funding from overseas and those who were self-financed were about equal at the beginning of the period, by the end of the period, significantly more students were funded through self-funding and institutional awards and waivers, indicating the increasing role of these two forms of funding relative to other overseas funding over the period.

A closer examination of the country of origin of the students who are funded through ‘other overseas sources’ (usually national governments), the largest segment of students were from Saudi Arabia and Malaysia (13% and 12.5% respectively), while only over 4,000 students (3.7%) from China were funded in this way (see ). This represents a shift in Chinese policy, opening up international education to the burgeoning middle classes in China who are able to afford it (Zhu & Reeves, Citation2019).

Table 3. Top three funding sources by student country of domicile.

The representation of subjects by types of funding is presented in . The data show that students who are self-funded are more evenly distributed across subjects. Such subjects as Law, History and Education appear to hold more intrinsic interest and more students enrol into these programmes even without financial support. Funded students pursue mostly Engineering degrees, followed by Physical, Biological, IT, Social and Business studies – areas that presumably would be helpful to governments funding these students, often with mandatory return/service clauses (see Brooks & Waters, Citation2021).

Table 4. Subject by top three types of funding.

Considering and the connection between institutions and funding, University of Nottingham is the most ‘generous’ university in the UK having awarded the greatest number of tuition fee waivers to international doctoral students since 1998. It offered over 6,000 awards, twice the number in comparison to its runner up – University of Birmingham with 3,155 tuition waivers. Universities of Cambridge and Oxford – accustomed to being at the top of all league tables – are only in the fifth and seventh places respectively, providing less tuition support to their international doctoral students. However, the Oxbridge are the top two institutions which have the greatest number of international students, who are funded by foreign governments/using other overseas sources. This indicates that these elite institutions place the burden of international doctoral student fees on students or on their national governments. In contrast, University of Loughborough and University of Aberdeen – both outside of the Russell Group – invest in the development of the newer generation of international academic researchers.

Table 5. Top three funding sources by institution.

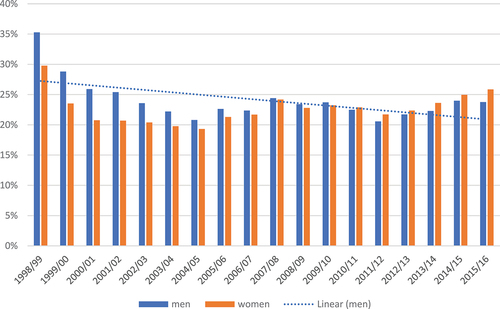

Weighting the proportions of the cohort of men and women by year in terms of funding they received over the years demonstrates several important findings (). First, the overseas funding distribution used to favour men until around 2005, when the gap began to flatten. Then from 2010 female students started receiving more funding than men.

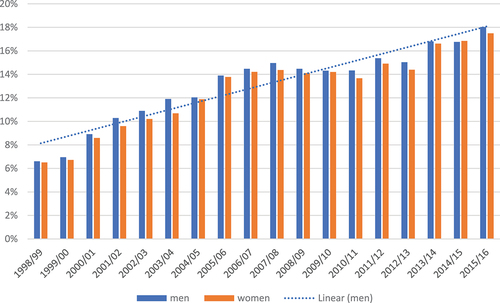

As for those students who are funded by British universities, there is nearly no difference in the funding distribution between the genders; 0.4% more men on average receive tuition aid from universities in the UK for their doctorate education. In 1998 only 7% of international students enrolled in doctoral programmes in the UK received funding from their host institutions, while in 2015 18% of men and 17% of women were awarded tuition fee waivers and bursaries. This is a positive trend, however, not promising enough in comparison to top US institutions or European institutions, in which PhD students tend to be fully funded, at least for tuition fees.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

We sought to explore the implications of the framing of the desirable international student as not only the ‘Best and Brightest’, but also one that can afford international tuition and subsistence – or access such assistance from overseas funding bodies – on the diversity of international doctoral students as knowledge producers in UK universities. Our initial contention was that these portrayals, embedded in a marketized system of HE, would result in limited diversity in the international doctoral student body. Through an analysis of HESA data from 1998 to 2014, we endeavoured to analyse the personal characteristics of these students, to understand their profiles and to reflect on the implications of these profiles for advancing a global tapestry of knowledge production and internationalisation in research. Our analysis confirmed a number of our initial contentions and revealed several key findings.

International doctoral students are primarily engaged in research. Our analysis revealed that less than 1% of the cohort was enrolled in taught doctoral programmes. This strengthens our claim about the important role of international doctoral students in contributing to research and science. Closely aligned with this focus, international doctoral students – with little variance by gender or country of domicile – were drawn to the more prestigious research-focused Russell group and Oxbridge universities. This indicates that these institutions bear the brunt of the responsibility for diversity in knowledge creation, not only in the UK, but with important effects on the global system of knowledge production. We revealed that some universities are rising to this challenge better than others; however, with only 13.7% of international doctoral students funded by universities, this number still indicates that these students are likely viewed, at least partially as economic subjects.

We show that the largest source of tuition funds for international doctoral students is self-funding (36.8%), followed by overseas providers (23.3%) and tuition waivers from UK institutions (13.7%). This combined with the fact that most students were in Russell group/Oxbridge universities, confirms our initial proposition that the marketized nature of UK HE, limits those who can access international doctoral programmes to those who are ‘Best and Brightest’ (i.e. as evidenced by their acceptance to top universities) and able to pay tuition and fees or are privileged to be financially supported by their home governments (see Campbell & Neff, Citation2020).

We reveal subject preferences across the cohort by country of origin. The top three subjects among US students are historical and philosophical studies, social studies and languages, while Chinese and Malaysian students are heavily skewed towards engineering and technology, physical/biological sciences and business and administrative studies. This indicates that there may be a lack of diversity in some of these disciplines, an issue that has been noted in other studies, particularly in relation to Chinese and Indian students in the UK (An Ran, Citation1999; Lomer, Citation2017). This calls into question the diversity of particular fields, even when there are a considerable number of international students.

Women are underrepresented in the cohort, and particularly in STEM subjects and more lucrative professional programmes. However, the gender gap has been steadily decreasing in the overall cohort in recent years. Women’s chances to attain funding (from overseas sources and institutions), while once disadvantaged, has grown to parity. Thus, the position of women international doctoral students has certainly ameliorated over time, however, there are still significant gaps. We argue that a physical absence/exclusion from research areas, is akin to an epistemic exclusion from the field and could have significant effects on the quality of knowledge production (see Longino, Citation1990; Pöyhönen, Citation2017), and also its optimistic role in promoting a more equitable global society (see Bernal & Villalpando, Citation2002; Montoya & Valdes, Citation2008). Thus, a limited pool of international doctoral students, is likely hampering both utilitarian and ethical aims of knowledge diversity.

While these findings from our analysis are helpful to understand issues of diversity in international doctoral students and knowledge production, there is a considerable amount that is unknown, primarily due to missing data. In this way our study was confounded by missing and spotty data collection. Moreover, the difficulty in accessing data, particularly the cost, sheds light on the commercialised nature of international students in the UK. Our analysis was significantly truncated from our original intentions. We were not able to follow individual trajectories; explore socio-economic status, caring responsibilities, disabilities, race or ethnicity. Importantly, these categories are tracked for UK ‘home’ students and incorporated into access/widening participation programmes. While it is in not certain that having the data would mean that changes would be made, we argue that more robust tracking of these variables would at the least provide institutions with the option to incorporate greater diversity. While we know the sources of tuition fees, we do not know how international students fund their living, research expenses, etc. as HESA does not gather those data. Yet this is particularly important because without this data, it is difficult to understand how doctoral students are supporting themselves or the profiles of these students and analyse equity issues. This is particularly important because there is a lack of research and discussion of international (doctoral) students’ tuition fees sources and their general financial welfare in the academic literature, a great omission. This has particularly come to the fore in the COVID-19 pandemic in which international students are reported as relying on food banks (Popp, Citation2021), while public representations of international students are often aligned with affluent stereotypes (see Mittelmeier & Cockayne, Citationforthcoming).

The HESA data has likewise proven to be considerably nationally focused. This focus tends to hide individual characteristics of diversity and homogenise populations. For example, we know that China is the biggest sender, but it is difficult to understand the profile of this cohort because markers for SES, ethnicity and race are not collected. With reports circulating about minority oppression in China (e.g. Millward & Peterson, Citation2020), this information could be particularly useful to understand the role of international doctoral education in perpetuating inequalities in knowledge production. Notably, the absence of this data is in opposition to statistical data which are available for ‘home’ British doctoral students. As Tannock (Citation2018) argues, these issues – particularly juxtaposed against the UK’s widening participation mandate – is striking in its neglect of equality for international students, demonstrating that these issues are not on the political agenda. Rather the UK government/institutions are more interested in providing equality within their own borders, than assuring that HE is fostering a truly diverse population of knowledge producers. In this way, there appears to be an attitude of ‘no data, no accountability, no problem’. If the UK does not collect the appropriate data, then the ‘problem’ cannot actively be formulated and identified. This results in a form of externalization of responsibility in which national policies and programmes attract and recruit international students, without care for the diversity of the cohort, or the repercussions of the apparent lack of diversity. This reflects a neoliberal form of internationalisation (Stein, Citation2021), and it seems unclear the extent to which ‘internationalisation’ – a term often associated with positive and optimistic human connectivity, such as cosmopolitanism, global citizenship, and humanitarianism (Bamberger et al., Citation2019) – in doctoral education is contributing to a truly global knowledge system.

While we have examined the UK case, our study has wider implications, given that the UK is a top destination for international doctoral students, and thus plays an oversized role in the production of knowledge, and future knowledge producers. Moreover, the practices in the UK are likely reflective of other countries, particularly Canada and Australia. Finally, we argue that the current system of UK international student recruitment and funding are detrimental to creating a truly global tapestry of knowledge production; it advances a form of neoliberal internationalisation that undermines the contribution that diversity can make to science.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the special issue editors for their encouragement and support throughout the publication process. We are grateful for the comments and suggestions of the anonymous peer reviewers. The second author was supported in this research by the Golda Meir Post-Doctoral Fellowship Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexandra Olenina

Alexandra Olenina is a PhD student at the IOE, UCL.

Annette Bamberger

Annette Bamberger is a Golda Meir Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Olga Mun

Olga Mun is a doctoral student and her main research interest is in the topics of epistemic injustice across all levels of education and across national borders with a focus on higher education and the process of knowledge production in academic institutes and universities.

Notes

References

- Arday, J. (2020). Fighting the tide: Understanding the difficulties facing Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Doctoral Students’ pursuing a career in Academia, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(10), 972–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777640

- Babones, S. (2016). Interpretive Quantitative Methods for the Social Sciences. Sociology, 50(3), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.2307/26555040

- Bamberger, A., Morris, P., & Yemini, M. (2019). Neoliberalism, internationalisation and higher education: Connections, contradictions and alternatives. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(2), 203–216. doi:10.1080/01596306.2019.1569879

- Bamberger, A. (2018). Academic degree recognition in a global era: The case of the doctorate of education (EdD) in Israel. London Review of Education, 16(1), 28–39. doi:10.18546/LRE.16.1.04

- Bamberger, A. (2022). Between foreigners and family: Social media representations of international students in Israeli universities. In A. Hayes, and S. Findlow (Eds.), Constructions of (Inter-)national Students in the Middle East:. Comparative Critical Perspectives: Routledge.

- Bernal, D. D., & Villalpando, O. (2002). An apartheid of knowledge in academia: The struggle over the” legitimate” knowledge of faculty of color. Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/713845282

- Bhopal, K., Brown, H., & Jackson, J. (2016). BME academic flight from UK to overseas higher education: Aspects of marginalisation and exclusion. British Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3204

- Bhopal, K., & Pitkin, C. (2020). ‘Same old story, just a different policy’: Race and policy making in higher education in the UK. Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(4), 530–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1718082

- Bloom, J. (2020). Coronavirus: Universities fear fall in lucrative overseas students. BBC. Retrieved on May 21, 2020, Retrieved on: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52508018

- Bolsmann, C., & Miller, H. (2008). International student recruitment to universities in England: Discourse, rationales and globalisation. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 6(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767720701855634

- Brooks, R., & Waters, J. (2021). International students and alternative visions of diaspora. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(5), 557–577.

- Brooks, R., & Waters, J. (2011). Student mobilities, migration and the internationalization of higher education. Springer.

- Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2013). Encounters with racism and the international student experience. Studies in Higher Education, 38(7), 1004–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.614940

- Campbell, A., & Neff, E. (2020). A systematic review of international higher education scholarships for students from the Global South. Review of Educational Research, 90(6), 824–861. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320947783

- Davies, C. (2020). UK’s old university towns hit by Covid-19 ‘double whammy. The Guardian. 25 May, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/17/the-uk-towns-and-cities-hit-by-covid-19-double-whammy

- De Vita, G., & Case, P. (2003). Rethinking the internationalisation agenda in UK higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877032000128082

- Education strategy. (2021). International Education strategy 2021. Retrieved on February 12, 2021, from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/international-education-strategy-2021-update/international-education-strategy-2021-update-supporting-recovery-driving-growth

- Findlay, A. M., McCollum, D., & Packwood, H. (2017). Marketization, marketing and the production of international student migration. International Migration, 55(3), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12330

- Gorard, S. (2006). Towards a judgement-based statistical analysis. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690500376663

- Gov UK. (2021). Government announces £50 million to support students impacted by Covid-19. Retrieved on February 2, 2021, from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-announces-50-million-to-support-students-impacted-by-covid-19

- Intemann, K. (2009). Why diversity matters: Understanding and applying the diversity component of the National Science Foundation’s broader impacts criterion. Social Epistemology, 23(3–4), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691720903364134

- Kim, T., & Ng, W. (2019). Ticking the ‘other’ box: Positional identities of East Asian academics in UK universities, internationalisation and diversification. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 3(1), 94–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2018.1564886

- Kwiek, M. (2015). The internationalization of research in Europe: A quantitative study of 11 national systems from a micro-level perspective. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(4), 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315572898

- Lee, J., Jon, J. E., & Byun, K. (2017). Neo-racism and neo-nationalism within East Asia: The experiences of international students in South Korea. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316669903

- Leyland, C. (2011). Does the rebranding of British universities reduce international students to economic resources? A critical discourse analysis. NOVITAS-ROYAL, 5(2).

- Lomer, S. (2017). Recruiting international students in higher education: Representations and rationales in British policy. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Lomer, S., Papatsiba, V., & Naidoo, R. (2018). Constructing a national higher education brand for the UK: Positional competition and promised capitals. Studies in Higher Education, 43(1), 134–153.

- Longino, H. (1990). Science as Social Knowledge: Values and objectivity in scientific inquiry. Princeton University Press.

- Ma, Y. (2020). Ambitious and Anxious. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Maker, C. J. (2020). Identifying exceptional talent in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: Increasing diversity and assessing creative problem-solving. Journal of Advanced Academics, 31(3), 161–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X20918203

- Marginson, S. (2011). Higher education and public good. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00496.x

- Mateos-Gonzalez, J. (2019). Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies [ Doctoral dissertation, Durham University].

- McManus, C., Neves, A. A. B., Maranhão, A. Q., Souza Filho, A. G., & Santana, J. M. (2020). International collaboration in Brazilian science: Financing and impact. Scientometrics, 125(3), 2745–2772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03728-7

- Mignolo, W. D. (2018). Foreword. On pluriversality and multipolarity (Reiter, B. Ed.). In Constructing the Pluriverse (pp. ix–xvi). Duke University Press.

- Millward, J., & Peterson, D. (2020). Global China: China’s system of oppression in Xinjian: How it developed and how to curb it. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FP_20200914_china_oppression_xinjiang_millward_peterson.pdf

- Mittelmeier, J. & Cockayne, H. (forthcoming). Global representations of international students in a time of crisis: A thematic analysis of Twitter data during COVID-19. International Studies in Sociology of Education.

- Montoya, M. E., & Valdes, F. (2008). Latinas/os and the politics of knowledge production: Latcrit scholarship and academic activism as social justice action. Ind. LJ, 83, 1197.

- Mwangi, C. A. G., Latafat, S., Hammond, S., Kommers, S., Thoma, H. S., Berger, J., & Blanco-Ramirez, G. (2018). Criticality in international higher education research: a critical discourse analysis of higher education journals. Higher Education, 76(6), 1091–1107.

- Neumann, R. (2002). Diversity, doctoral education and policy. Higher Education Research & Development, 21(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360220144088

- OECD. (2020). Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators. https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en

- Popp, A.(2021). The international students struggling to feed themselves in lockdown Channel 4 News. Retrieved on February 25, 2021, Retrieved on: https://www.channel4.com/news/the-international-students-struggling-to-feed-themselves-in-lockdown

- Pöyhönen, S. (2017). Value of cognitive diversity in science. Synthese, 194(11), 4519–4540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1147-4

- Ran, A. (1999) Learning in two languages and cultures: The experience of Mainland Chinese families in Britain. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Reading.

- Ridinger, R. (2014). Tracking the rainbow: Recent trends in LGBT reference and collection development. Reference Reviews, 28(7), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1108/RR-11-2013-0297

- Robertson, S. (2011). Cash cows, backdoor migrants, or activist citizens? International students, citizenship, and rights in Australia. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(12), 2192–2211. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.558590

- Sato, T., & Hodge, S. R. (2009). Asian international doctoral students’ experiences at two American universities: Assimilation, accommodation, and resistance. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 2(3), 136. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015912

- Shahjahan, R. A., & Kezar, A. J. (2013). Beyond the “national container” addressing methodological nationalism in higher education research. Educational Researcher, 42(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12463050

- Shields, R. (2019). The sustainability of international higher education: Student mobility and global climate change. Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 594–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.291

- Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Bruce, J., & Suša, R. (2016). Towards different conversations about the internationalization of higher education. Comparative and International Education/éducation Comparée Et Internationale, 45(1), 2.

- Stein, S., & de Andreotti, V. O. (2016). Cash, competition, or charity: International students and the global imaginary. Higher Education, 72(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9949-8

- Stein, S. (2021). Critical internationalization studies at an impasse: Making space for complexity, uncertainty, and complicity in a time of global challenges. Studies in Higher Education, 46(9), 1771–1784. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1704722

- Stockfelt, S. (2018). We the minority-of-minorities: A narrative inquiry of black female academics in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(7), 1012–1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1454297

- Sun, F. (2020). Sino–UK science and technology collaboration in field of people’s livelihood. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 18(4), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2020.1855857

- Tannock, S. (2018). Educational equality and international students. Justice Across Borders? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wang, T., & Li, L. Y. (2011). ‘Tell me what to do’vs.‘guide me through it’: Feedback experiences of international doctoral students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411402438

- Woldegiyorgis, A. A., Proctor, D., & de Wit, H. (2018). Internationalization of research: Key considerations and concerns. Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318762804

- Zanoni, P., Janssens, M., Benschop, Y., & Nkomo, S. (2010). Guest editorial: Unpacking diversity, grasping inequality: Rethinking difference through critical perspectives. Organization, 17(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508409350344

- Zanoni, P., & Janssens, M. (2004). Deconstructing difference: The rhetoric of human resource managers’ diversity discourses. Organization Studies, 25(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604038180

- Zhu, L., & Reeves, P. (2019). Chinese students’ decisions to undertake postgraduate study overseas. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(5), 999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2017-0339