Abstract

Food fortification is used as a nutrition support strategy in aged care homes, for residents who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. The aim of this review was to determine the scope and strength of published works exploring relationships between food fortification strategies, mode of delivery and sustainability in aged care homes. Literature from four databases and grey literature was searched. A total of 3152 articles were screened. Seventeen studies were included. Results showed that the majority of studies used pre-made food fortification, rather than fortifying foods on-site. There was heterogeneity across studies, including the mode of delivery and ingredients used for food fortification. Only two studies measured any aspect of costs. No clear sustainable strategies for implementing food fortification in this setting could be identified. Research is required to provide further insight into the acceptability and sustainability of food fortification interventions.

Introduction

Food-first nutrition support strategies use food and beverages to counteract unintended weight loss and malnutrition (Forbes Citation2014). In the aged care sector, many homes use food fortification to support the nutritional adequacy of menus (Forbes Citation2014). Food fortification delivers additional macronutrients and/or micronutrients to counteract common nutrient inadequacies observed in older adults. This strategy involves the addition of energy and nutrient-dense ingredients (either common kitchen ingredients or commercial supplement powders) to foods or beverages, without increasing the portion size (Kral and Rolls Citation2004; Dunne Citation2009). Common on-site food fortification strategies include the addition of ingredients high in energy and protein, such as milk powder, butter, cream or cheese. Fortified foods can also be commercially-made and purchased by foodservices. These pre-made fortified foods are usually not as versatile as on-site fortification because they focus on a single mode of delivery. The mode of delivery, refers here to any food or beverage to which an ingredient is purposely added, as a food fortification strategy. The mode of delivery is often through foods that are commonly consumed by the target population, for example bread (van Til et al. Citation2015). Taste fatigue can be an issue when offering a single food or beverage over a period of time, which can be a common issue with oral nutrition supplements (ONS) (Lawson et al. Citation2000). Food fortification has the potential to be spread across the menu, in food and beverages served at all meals and mid-meals, which may prevent taste fatigue (Gall et al. Citation1998). In Australia, there is currently no best practice model for the delivery of food fortification strategies across the menu in aged care homes for residents who require nutrition support.

There are multiple factors that may contribute to a loss of body weight, lean body mass and subsequently an increased risk of malnutrition in older adults (Gaskill et al. Citation2008). Some of these factors have been recognised as the “nine D’s”, which include dysfunction, drugs, dementia, dysgeusia, dysphagia, diarrhoea, depression, disease and poor dentition (Agarwal et al. Citation2016). These factors can lead to difficulties with feeding, digestion, absorption and excretion of nutrients and gastrointestinal issues (Fávaro-Moreira et al. Citation2016) Ageing itself contributes to a higher risk of malnutrition due to changes in appetite known as the “anorexia of ageing”, often resulting in a lack of appetite or early satiety (Morley Citation1997). Therefore, many older Australians have inadequate intakes of energy, protein and key micronutrients (Iuliano et al. Citation2013). Adequate protein and energy intake is essential for slowing down the loss of lean body mass that occurs with ageing (Bauer et al. Citation2013). Additionally, adequate intakes of vitamins and minerals that play key roles in the body’s antioxidant defence system, wound healing, neurological function and bone health contribute to healthy ageing (National Health and Medical Research Council Citation2006). In Australian aged care homes, malnutrition rates were ∼50% in 2008–09, however no recent studies measuring malnutrition rates in this setting have been identified (Gaskill et al. Citation2008; Woods et al. Citation2009).

The sustainability of food fortification strategies within the foodservice systems of aged care homes is yet to be determined. In 2015, Lam et al. conducted focus groups and interviews with key stakeholders, regarding a food-first micronutrient food fortification strategy in Canadian aged care homes. This study found that food-first strategies were preferred to ONS to prevent micronutrient deficiencies in residents (Lam et al. Citation2015). Additionally, key stakeholders saw outsourcing production to pre-made fortified products as a solution, although residents and families had concerns around safety and efficacy. Using foods that most residents consumed was considered the most appropriate mode of delivery for fortification. Participants identified coffee, juice, tea and milk to be appropriate beverage modes of delivery and condiments, toppings, soup and dessert were identified as appropriate food modes of delivery, with ice cream being the first preference of residents. Staff highlighted the importance of choosing a mode of delivery that can be suitable across different textured diets, such as porridge or custard and that variation would be key to maximise consumption. To our knowledge, there is no other qualitative research on food fortification in this setting.

In aged care homes, the menu is often the sole source of nutrition for residents (Abbey et al. Citation2015). Therefore, the foodservice system plays an important role in the nutritional care provided to residents. Two recent systematic reviews focussed solely on nutrition intake and nutrition status outcomes of food fortification in this setting, but did not mention the foodservice system nor sustainability of food fortification within this system (Morilla-Herrera et al. Citation2016; Douglas et al. Citation2017). Additionally, these reviews only searched the published literature in electronic journal databases and to our knowledge, no other review has searched grey literature.

There is also limited literature on the cost of food fortification strategies. Providing evidence of the economic savings associated with food fortification is critical to obtaining management support to commence and sustain these practices into the foodservice system of aged care homes (Kimmons et al. Citation2012). Nutrition champions may also help the sustainability of nutrition strategies in aged care homes, and consequently maintain or improve the nutrition status of residents (Byles et al. Citation2009; Gaskill et al. Citation2009). In this setting, a nutrition champion is a person who supports and advocates for the nutritional care of residents and may also be referred to as a nutrition coordinator or nutrition assistant. Previous research has found that residents of aged care homes with dedicated nutrition coordinators were more likely to maintain or improve their nutrition status, whereas residents of homes without a nutrition coordinator were significantly more likely to have deteriorating nutrition status (Gaskill et al. Citation2009). Similarly, in 2009 the Australian Government Department of Health & Ageing funded the Encouraging Best Practice Nutrition and Hydration in Residential Aged Care project, which took place in nine aged care homes throughout New South Wales, Australia and established a nutrition champion at each facility to help with the success of the project (Byles et al. Citation2009).

To our knowledge, no previous reviews on food fortification in this setting have focussed on identifying mode of delivery and sustainability of food fortification strategies in aged care homes from a foodservice perspective. The purpose of this narrative review was to determine the scope and strength of published works exploring relationships between food fortification strategies, mode of delivery and sustainability in aged care and discuss implications for practice.

Methods

Search strategy

Four electronic databases were searched for studies published up until February 2019, including PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL and Scopus. Grey literature was searched to the first fifty results from Google, Google Scholar, Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Department of Health and Food Standards Australia and New Zealand.

Search terms were identified by the researchers following consultation with a librarian. Controlled vocabulary was used when available. Search terms used in this review include; “aged care” OR “residential care” OR “long term care” OR “long term residential care” OR institutionali?ed OR “nursing home*” OR “aged care home*” OR “aged care facilit*” OR “aged institution*”) AND ((micronutrient* OR “trace element*” OR vitamin* OR mineral*) OR (“food fortification” OR “protein-enrich*” OR “fortified food*” OR “food-based” OR “food modification” OR “meal modification” OR “functional food” OR “nutrient dens*” OR “fortified meal*” OR “fortification of food”)).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were considered for inclusion if they described an intervention using food fortification and met the following criteria: (1) study population was older adults living in residential aged care homes, (2) interventions included food fortification with protein, energy and/or micronutrients, (3) reported outcomes identifying mode of delivery, nutrition intake and if available nutrition status and intervention costs, (4) published in English and (5) available in full-text. Studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded from this review. There were no restrictions placed on study design or year of publication.

Study selection

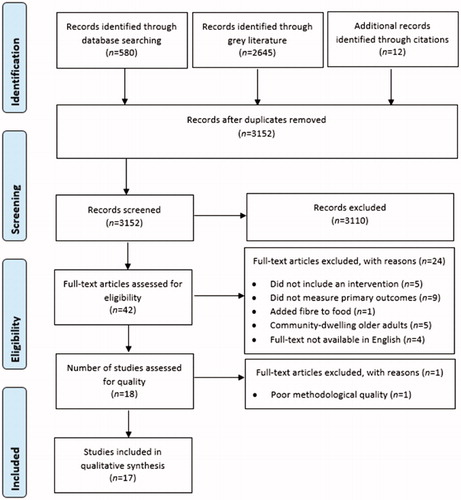

The electronic databases yielded a total of 580 journal articles. After duplicates were removed, a total of 495 journal articles were retrieved and a title and abstract check was performed for inclusion, yielding 20 potential results. Additionally, the grey literature search yielded 2645 results and a title and abstract check was performed, yielding 10 potential results. An additional 12 articles were identified from citations. Full-text was screened for 42 articles. Those deemed eligible underwent full-text screening and were appraised for quality by two reviewers before final inclusion in this review, to decrease subjectivity and selection bias. In case of a disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer was available. The flow chart of study selection is shown in .

Quality appraisal, levels of evidence and data extraction

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology was used to assess study quality in this review (Joanna Briggs Institute Citation2018a). Two JBI Critical Appraisal Checklists were used depending on the study design: (1) JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials and (2) JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Non-Randomised Experimental Studies) (Joanna Briggs Institute Citation2018a). Eighteen studies underwent critical appraisal. One study was excluded due to poor methodological quality. A score of 4-6 on the JBI critical appraisal checklist indicated moderate quality and a score of 7 and above indicated high quality, as used previously by Luctkar-Flude and Groll (Citation2015). Due to the paucity of research in this area, a cut-off score of 4 was established for each of the JBI checklists in this study. Additionally, the Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence was applied to each study (Joanna Briggs Institute Citation2018b). Data from the 17 included studies was extracted by one reviewer using a modified JBI Data Extraction Form. No meta-analysis could be conducted due to heterogeneity between the studies.

Results

Study characteristics

Overall there was great heterogeneity across the studies included in this review. The study characteristics are shown in . Sample sizes ranged from 15 to 126 participants and the studies went for a duration of 6 days to 12 months. Eleven of the 17 studies were randomised controlled trials and 6 were quasi-experimental studies. The included studies were conducted in 11 countries, primarily in Europe. Some of these studies were conducted by the same research group, from France. Five quasi-experimental studies were rated moderate quality and the remaining 12 studies were rated high quality (11 randomised controlled trials and 1 quasi-experimental) using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklists (Supplementary Material).

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Food fortification in aged care homes

The included studies were conducted in aged care residential settings, including a rehabilitation centre and “sheltered” accommodation. The food fortification strategies are shown in . Only six of the studies fortified on-site and the remaining studies used pre-made fortified foods. Studies used fortification strategies to increase protein, energy, vitamin D, calcium, folate/folic acid and/or other micronutrients. Fortification occurred through the additional of milk powder, double cream, butter, cream, cheese, oil, sour cream, hydrolysed starch, rapeseed oil and other common kitchen ingredients and/or commercially-made supplement powders. The most common mode of delivery were soups, juices, cereals, desserts, yoghurt, cheese and bread. Mode of delivery varied across the studies, including across the day in 6 studies (Tolbert Citation2004; Smoliner et al. Citation2008; Grieger and Nowson Citation2009; Leslie et al. Citation2013; van Til et al. Citation2015; Beelen et al. Citation2017), in breakfast only by 2 studies (Bermejo et al. Citation2008; van Wymelbeke et al. Citation2016), in breakfast and lunch by 1 study (Castellanos et al. Citation2009), in lunch and dinner by 3 studies (Odlund Olin et al. Citation2003; Bonjour et al. Citation2013; Bonjour et al. Citation2015) and the delivery was unspecified for 5 studies (Kwok et al. Citation2001; Bonjour et al. Citation2009; Mocanu et al. Citation2009; Bonjour et al. Citation2011; Costan et al. Citation2014).

Table 2. Food fortification strategies.

Sustainability of food fortification in aged care homes

The majority of studies used pre-made fortified foods, with only six studies conducting food fortification on-site and incorporating these strategies into the menu. Only two studies measured the costs associated with their intervention. Both of these studies were randomised controlled trials using fortified menu items to increase energy density. Leslie et al. (Citation2013) added 50 mL of double cream to cereal, porridge, soup and dessert, 8 g butter to potatoes and offered a 250 mL malted milk drink once a day to residents, providing up to an additional 1673 kJ/day. The estimated cost of this intervention was $AUD1.81 (£0.97) per resident per day, as of January 2011. In Sweden, Odlund Olin et al. (Citation2003) added cream, cheese, oil, butter and other common kitchen ingredients to hot meals and cream, sour cream and/or hydrolysed starch to desserts. This intervention provided up to an additional ∼2100kJ/day (500 kcal/day) and cost $AUD0.18 (0.11€) per resident per day. The two costs varied considerably at $AUD0.18 and $AUD1.81 per resident per day, which is likely due to the heterogeneity between interventions. Neither of these studies reported the costs of staff time to deliver food fortification.

Only three studies mentioned some aspect of acceptability in their results and discussion. Grieger and Nowson (Citation2009) conducted an acceptability questionnaire with staff and residents and found that 67% of staff and 92% of residents believed it would not be difficult to continue using fortified milk. Whereas Leslie et al. (Citation2013) noted that the success of the intervention depended on cooperation and awareness of staff. The study by Costan et al. (Citation2014) reported 91% of participants consuming the fortified bread daily for 12 months, indicating high acceptability. Lastly, in terms of sustainability of the food fortification strategies, two studies discussed a nutrition champion. Grieger and Nowson (Citation2009) had a researcher visit the aged care homes weekly to provide encouragement to staff to use the fortified milk, as well as provide encouragement to the residents consuming the fortified milk. Leslie et al. (Citation2013) noted that the aged care homes with co-operative and interested staff saw the greatest improvements. The majority of studies did not consider the menu, costs, acceptability nor using a nutrition champion.

Discussion

The purpose of this narrative review was to determine the scope and strength of published works exploring relationships between food fortification strategies, mode of delivery and sustainability in aged care and discuss implications for practice. Overall, the studies included in this review suggest that food fortification strategies are effective in increasing protein, energy and micronutrient intakes in older adults, as concluded in two recent systematic reviews (Morilla-Herrera et al. Citation2016; Douglas et al. Citation2017). Given that fortified foods provide more energy, protein, vitamins and minerals without increasing the volume of food, it is not surprising that most studies reported an improvement in nutrition intake and status (Kral and Rolls Citation2004; Dunne Citation2009). In the few studies that compared food fortification with other interventions, such as oral nutrition supplements or larger portions of food, the results were in favour of food fortification for nutrition intake, nutrition status and adherence (Bermejo et al. Citation2008; van Wymelbeke et al. Citation2016). Whilst the literature has shown that food fortification can result in improvements in nutrition intake and status, there is currently no best practice model for food fortification strategies or mode of delivery within the menu.

The majority of the studies used pre-made fortified foods, rather than utilising foodservice staff to undertake fortification on-site. These products were produced off-site and provided to the aged care homes. This was the chosen method for nearly all of the studies increasing micronutrient intake. Primarily dairy foods were used to provide additional micronutrients, including folic acid, vitamin D and calcium, in milk, cheese, yoghurt, margarine and bread. These nutrients were previously found to be poorly consumed, with the mean intake of Australian aged care residents below recommendations (Iuliano et al. Citation2013). These strategies were implemented daily and ranged from 1-2 serves of fortified foods per day or throughout the day for the fortified milks. Some of the fortified foods are considered staple products in the countries that carried out the studies. In agreeance with Lam et al. (Citation2015), this finding highlighted that fortification should ideally focus on foods that are already commonly consumed by older adults (Costan et al. Citation2014; van Til et al. Citation2015; van Wymelbeke et al. Citation2016).

Previous systematic reviews concluded that there is limited evidence for the cost of food fortification interventions (Morilla-Herrera et al. Citation2016; Douglas et al. Citation2017). In this review, the only two studies to measure intervention costs were focussed on increasing energy intake through on-site food fortification with common kitchen ingredients. These costs came to $AUD0.18 and $AUD1.81 per resident per day, which is a considerable difference. One study was conducted in Sweden and the other in the United Kingdom, indicating that most countries, including Australia have no data on the cost of food fortification strategies (Odlund Olin et al. Citation2003; Leslie et al. Citation2013). Additionally, none of the studies using pre-made fortified foods reported on the costs. Cost has previously been identified by key stakeholders as being a major barrier to implementing food fortification strategies in aged care homes (Lam et al. Citation2015). It would be beneficial to have information on the cost of food fortification produced on-site and pre-made, in order to compare the costs involved. Food fortification produced on-site would also incur other costs, such as cost of staff time to carry out and deliver this strategy. However it is currently unknown how these costs would compare to the costs of pre-made fortified foods.

Overall, only three studies mentioned some aspect of acceptability of their intervention from staff or residents (Grieger and Nowson Citation2009; Leslie et al. Citation2013; Costan et al. Citation2014). These studies found that factors such as cooperation and awareness of staff and adherence play a role in the acceptability of food fortification to both staff and residents. While few studies mentioned a nutrition champion, in those where there was a champion encouraging the use of the fortified products, there was greater success with the intervention (Grieger and Nowson Citation2009; Leslie et al. Citation2013). Therefore, this review further supports that nutrition champions may be fundamental for the success and sustainability of food fortification in aged care homes.

This review has identified potential enablers for sustainability, including low cost and the ease of use of the fortification ingredients, which would minimise the costs associated with staff time. Additionally, product availability will ensure that the aged care home can continue purchasing it long-term. When choosing foods vehicles for fortification, it appears that staple foods or foods commonly consumed by the older population are the most appropriate vehicles. However, the major barriers to sustainability include a lack of information regarding comprehensive costs of food fortification strategies, including the cost of staff time, the availability of these foods post-intervention and the continuation of a nutrition champion long-term. We do not currently have information regarding how much staff time it takes to implement food fortification strategies, the cost of staff time and whether or not these strategies are feasible outside of a research study. As part of an acceptability questionnaire, there were two negative comments from staff regarding the extra work required to serve fortified milk to residents and to remember which residents required it (Grieger and Nowson Citation2009). A recent study in community-dwelling older adults found that participants were disappointed that they had no way of purchasing the intervention products, fortified bread and readymade meals after the intervention period (Ziylan et al. Citation2017). Additionally, whilst a nutrition champion may improve the success of an intervention, there are issues with staff changes and continued funding for such positions at the conclusion of the intervention.

Lack of homogeneity between study design, interventions and outcomes was a limitation of this review and of previous reviews on food fortification in these settings (Trabal and Farran-Codina Citation2015; Morilla-Herrera et al. Citation2016). This could be in part due to different countries using a wide variety of fortification strategies and the lack of consensus globally on what is best practice food fortification in aged care. Overall most studies were only short-term, with only two studies having a duration of 12 months. Only one study followed up their participants after their intervention ceased and found that their nutrition status declined over time, indicating that sustainability of these interventions is crucial for maintaining nutrition status (Mocanu et al. Citation2009; Mocanu and Vieth Citation2013). Additionally, most studies looked at single nutrients, or just macronutrients or micronutrients, not at what would be the best combination for fortification strategies. Some studies were conducted by the same authors and had similar interventions and results, limiting their generalisability. It would be beneficial to see more studies exploring these interventions from a foodservice perspective, including the menu systems used in aged care homes. Additionally, in agreement with Douglas et al. (Citation2017), qualitative research with residents or staff in aged care homes may provide further insight into the acceptability and sustainability of food fortification interventions.

No clear sustainable strategies for implementing food fortification in these settings could be identified, although a nutrition champion may be beneficial. We propose that costs are of importance in the aged care sector and future research should include intervention costs of food fortification, as well as considering other strategies to support embedding food fortification within the foodservice system. Further research is required to provide further insight into the acceptability and sustainability of food fortification interventions.

Conclusion

This review provides further insight into the use of food fortification in aged care homes, as well as identifying potential foods in which fortification could be delivered. Future research should aim to provide data on intervention costs and sustainability of food fortification within foodservices to ensure that these strategies become part of the menu.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (153.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. D. P. Cave is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

References

- Abbey KL, Wright ORL, Capra S. 2015. Menu planning in residential aged Care-the level of choice and quality of planning of meals available to residents. Nutrients. 7(9):7580–7592.

- Agarwal E, Marshall S, Miller M, Isenring E. 2016. Optimising nutrition in residential aged care: A narrative review. Maturitas. 92(C):70–78.

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, Phillips S, Sieber C, Stehle P, Teta D, et al. 2013. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE study group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 14(8):542–559.

- Beelen J, De Roos N, De Groot L. 2017. Protein enrichment of familiar foods as an innovative strategy to increase protein intake in institutionalized elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 21(2):173–179.

- Bermejo LM, Aparicio A, Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, López-Sobaler AM, Andrés P, Ortega RM. 2008. Dietary strategies for improving folate status in institutionalized elderly persons. Br J Nutr. 101(11):1611–1615.

- Bonjour JP, Benoit V, Atkin S, Walrand S. 2015. Fortification of yogurts with vitamin D and calcium enhances the inhibition of serum parathyroid hormone and bone resorption markers: a double blind randomized controlled trial in women over 60 living in a community dwelling home. J Nutr Health Aging. 19(5):563–569.

- Bonjour JP, Benoit V, Payen F, Kraenzlin M. 2013. Consumption of yogurts fortified in vitamin D and calcium reduces serum parathyroid hormone and markers of bone resorption: a double-blind randomized controlled trial in institutionalized elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98(7):2915–2921.

- Bonjour JP, Benoit V, Pourchaire O, Ferry M, Rousseau B, Souberbielle JC. 2009. Inhibition of markers of bone resorption by consumption of vitamin D and calcium-fortified soft plain cheese by institutionalised elderly women. Br J Nutr. 102(7):962–966.

- Bonjour JP, Benoit V, Pourchaire O, Rousseau B, Souberbielle JC. 2011. Nutritional approach for inhibiting bone resorption in institutionalized elderly women with vitamin D insufficiency and high prevalence of fracture. J Nutr Health Aging. 15(5):404–409.

- Byles J, Perry L, Parkinson L, Bellchambers H, Moxey A, Howie A, Murphy N, Galliene L, Courtney G, Robinson I, et al. 2009. Encouraging best practice nutrition and hydration in residential aged care. Final report. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health & Ageing.

- Castellanos VH, Marra MV, Johnson P. 2009. Enhancement of select foods at breakfast and lunch increases energy intakes of nursing home residents with low meal intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 109(3):445–451.

- Costan AR, Vulpoi C, Mocanu V. 2014. Vitamin D fortified bread improves pain and physical function domains of quality of life in nursing home residents. J Med Food. 17(5):625–631.

- Douglas JW, Lawrence JC, Knowlden AP. 2017. The use of fortified foods to treat malnutrition among older adults: a systematic review. Quality Ageing Older Adults. 18(2):104–119.

- Dunne A. 2009. Malnutrition in care homes: improving nutritional status. Nurs Residential Care. 11(9):437–442.

- Fávaro-Moreira NC, Krausch-Hofmann S, Matthys C, Vereecken C, Vanhauwaert E, Declercq A, Bekkering GE, Duyck J. 2016. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv Nutr. 7(3):507.

- Forbes C. 2014. The ‘Food First’ approach to malnutrition. Nurs Residential Care. 16(8):442–445.

- Gall MJ, Grimble GK, Reeve NJ, Thomas SJ. 1998. Effect of providing fortified meals and between-meal snacks on energy and protein intake of hospital patients. Clin Nutr. 17(6):259–264.

- Gaskill D, Black LJ, Isenring EA, Hassall S, Sanders F, Bauer JD. 2008. Malnutrition prevalence and nutrition issues in residential aged care facilities. Australas J Ageing. 27(4):189–194.

- Gaskill D, Isenring EA, Black LJ, Hassall S, Bauer JD. 2009. Maintaining nutrition in aged care residents with a train-the-trainer intervention and nutrition coordinator. J Nutr Health Aging. 13(10):913–917.

- Grieger JA, Nowson CA. 2009. Use of calcium, folate, and vitamin D(3)-fortified milk for 6 months improves nutritional status but not bone mass or turnover, in a group of Australian aged care residents. J Nutr Elderly. 28(3):236–254.

- Iuliano S, Olden A, Woods J. 2013. Meeting the nutritional needs of elderly residents in aged-care: are we doing enough? J Nutr Health Aging. 17(6):503–508. eng.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. 2018a. Critical Appraisal Tools. Adelaide (Australia): Joanna Briggs Institute; [accessed 2019 Feb 2]. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. 2018b. Levels of Evidence. Adelaide (Australia): Joanna Briggs Institute; [accessed 2019 Feb 2]. http://joannabriggs.org/jbi-approach.html#tabbed-nav=Levels-of-Evidence.

- Kimmons J, Jones S, McPeak HH, Bowden B. 2012. Developing and implementing health and sustainability guidelines for institutional food service. Adv Nutr. 3(3):337–342.

- Kral TVE, Rolls BJ. 2004. Energy density and portion size: their independent and combined effects on energy intake. Physiol Behav. 82(1):131–138.

- Kwok T, Woo J, Kwan M. 2001. Does low lactose milk powder improve the nutritional intake and nutritional status of frail older Chinese people living in nursing homes? J Nutr Health Aging. 5(1):17–21.

- Lam IT, Keller H, Duizer L, Stark K, Duncan AM. 2015. Nothing ventured, nothing gained: Acceptability testing of micronutrient fortification in long-term care. J Nurs Home Res. 1:18–27.

- Lawson RM, Doshi MK, Ingoe LE, Colligan JM, Barton JR, Cobden I. 2000. Compliance of orthopaedic patients with postoperative oral nutritional supplementation. Clin Nutr. 19(3):171–175.

- Leslie WS, Woodward M, Lean ME, Theobald H, Watson L, Hankey CR. 2013. Improving the dietary intake of under nourished older people in residential care homes using an energy-enriching food approach: a cluster randomised controlled study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 26(4):387–394.

- Luctkar-Flude M, Groll D. 2015. A systematic review of the safety and effect of neurofeedback on fatigue and cognition. Integr Cancer Ther. 14(4):318–340.

- Mocanu V, Stitt PA, Costan AR, Voroniuc O, Zbranca E, Luca V, Vieth R. 2009. Long-term effects of giving nursing home residents bread fortified with 125 microg (5000 IU) vitamin D(3) per daily serving. Am J Clin Nutr. 89(4):1132–1137.

- Mocanu V, Vieth R. 2013. Three-year follow-up of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and bone mineral density in nursing home residents who had received 12 months of daily bread fortification with 125 μg of vitamin D(3). Nutr J. 12:137.

- Morilla-Herrera JC, Martín-Santos FJ, Caro-Bautista J, Saucedo-Figueredo C, García-Mayor S, Morales-Asencio JM. 2016. Effectiveness of food-based fortification in older people a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 20(2):178–184.

- Morley JE. 1997. Anorexia of aging: physiologic and pathologic. Am J Clin Nutr. 66(4):760.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2006. Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra (Australia): NHMRC.

- Odlund Olin A, Armyr I, Soop M, Jerstrom S, Classon I, Cederholm T, Ljungren G, Ljungqvist O. 2003. Energy-dense meals improve energy intake in elderly residents in a nursing home. Clin Nutr. 22(2):125–131.

- Smoliner C, Norman K, Scheufele R, Hartig W, Pirlich M, Lochs H. 2008. Effects of food fortification on nutritional and functional status in frail elderly nursing home residents at risk of malnutrition. Nutrition. 24(11–12):1139–1144.

- Tolbert SM. 2004. Enhancing weight gain in long-term care residents at risk for weight loss through protein and calorie fortification [master's thesis]. Johnson City (TN): East Tennessee State University.

- Trabal J, Farran-Codina A. 2015. Effects of dietary enrichment with conventional foods on energy and protein intake in older adults: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 73(9):624–633.

- van Til AJ, Naumann E, Cox-Claessens I, Kremer S, Boelsma E, de van der Schueren M. 2015. Effects of the daily consumption of protein enriched bread and protein enriched drinking yoghurt on the total protein intake in older adults in a rehabilitation centre: a single blind randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 19(5):525–530.

- van Wymelbeke V, Brondel L, Bon F, Martin-Pfitzenmeyer I, Manckoundia P. 2016. An innovative brioche enriched in protein and energy improves the nutritional status of malnourished nursing home residents compared to oral nutritional supplement and usual breakfast: FARINE + project. Clin Nutr Espen. 15:93–100.

- Woods JL, Walker KZ, Iuliano Burns S, Strauss BJ. 2009. Malnutrition on the menu: nutritional status of institutionalised elderly Australians in low-level care. J Nutr Health Aging. 13(8):693–698.

- Ziylan C, Haveman-Nies A, Kremer S, de Groot L. 2017. Protein-enriched bread and readymade meals increase community-dwelling older adults' protein intake in a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 18(2):145–151.