?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines how firm value (measured via stock prices) is related to corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure and how the institutional environment influences this relationship. To test our hypotheses, we apply textual analysis to our data on firms listed in the STOXX Europe 600 for the period 2008–2016. Our investigation of topic-specific CSR disclosure indicates that when firms shifted from voluntary to mandatory reporting, following the announcement of Directive 2014/95/EU, the association between their share price and CSR disclosure became significantly negative. For the period before the announcement, this relationship is either positive or statistically insignificant. We also show that the institutional environment can impact this relationship in four distinct ways: the level of CSR awareness, the level of employee protection, the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment. We find that the first two have a negative impact on the incremental value relevance of specific CSR disclosure, whereas the last two have a positive impact. Lastly, our results also indicate that the magnitude of (a) the relationship between a firm’s CSR disclosure and its value and (b) the impact that the firm’s institutional environment has on this relationship depends on the specific CSR topics.

1. Introduction

Since the early 2000s, corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting has both gained decisively in importance on the company level (KPMG, Citation2017; Stolowy & Paugam, Citation2018) and attracted considerable attention from policy makers. In 2014, the European Parliament issued directive 2014/95/EU (‘CSR directive’ hereafter); essentially, the CSR directive intended to trigger change towards a more sustainable economy (European Parliament, Citation2014). This directive proved an important step towards mandatory CSR reporting in Europe. The European Parliament announced this EU-wide shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting in April 2014; the CSR directive came into force in 2017. However, many critics point out that the directive fails to provide a distinct CSR reporting framework and to mandate assurance of the published CSR information.

The simultaneous switch from voluntary to mandatory reporting across the European Union (EU) as a result of a supranational regulation represents an exogenous regulation-driven shock to CSR disclosure and has considerable implications for CSR disclosure. For the purposes of our study, the scope of those implications provides an interesting setting in which to examine the relationship between firm value and CSR disclosure. Despite a growing body of research on CSR disclosure and the increase in relevant regulation, the relationship between these two is neither theoretically nor empirically clear. There are two main reasons for this persistent lack of clarity: first, the clash between contrary views on the impact of CSR activities on a firm’s value, namely the ‘shareholder expense view’ versus the ‘stakeholder maximization view’. Second, the fundamentally different nature of CSR disclosure compared to financial disclosure; specifically, the CSR topic under consideration, the form in which it is disclosed, as well as how it is used and by whom, all play an important role in determining this association.

For that reason, apart from traditional economic theory, socio-political theories – in particular legitimacy theory – are also useful in explaining voluntary CSR disclosure. Also the results of empirical research in this context are conflicting: some studies have found that the relationship between a firm’s value and CSR disclosure is positive (Cahan et al., Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2014), others have found that this relationship is negative (Richardson & Welker, Citation2001) and yet others have found no evidence for such a relationship in the first place (Cho et al., Citation2015; Freedman & Jaggi, Citation1988; Murray et al., Citation2006). Overall, however, the evidence that this relationship is positive tends to prevail.

One important point is that most research to date focuses on voluntary CSR disclosure. This, as Christensen et al. (Citation2019) argues, poses a ‘dual selection problem’ that may drive the predominantly positive findings. In a voluntary setting, firms can choose their CSR activities and the subsequent disclosure about such activities based on cost–benefit considerations. Differences in the institutional environment of firms may also help explain the inconsistent findings with regard to the effects of CSR disclosure. Some studies have found evidence that the institutional environment indeed influences the effect of CSR disclosure on firm value (Cahan et al., Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012, Citation2014). However, the direction of this relationship is currently unclear which also results from differences in the measures of the institutional environment.

The above overview shows that it is important to shed more light on how the institutional environment may impact the relationship between CSR reporting and a firm’s value. The CSR directive that made CSR reporting mandatory across the EU represents a unique setting for investigating this question. It simultaneously targets a multitude of countries with different institutional backgrounds.

This study aims to identify if the CSR topics that the EU directive covers are value-relevant and to clarify how the institutional environment affects their relevance. We examine each question separately. For that purpose we use textual analysis to generate CSR disclosure measures with respect to the topics the CSR directive mandates to disclose about: environmental matters, social matters, employee matters, human rights, corruption and bribery. We then use these topic-specific CSR disclosure measures for a two-step analysis. First, we analyze how these topic-specific disclosures may be relevant to a firm’s value. For this purpose we use a nested Ohlson (Citation1995) model to find out whether CSR disclosure influences share price. In this model we also account for the announcement of the CSR directive and are thus able to determine the value-relevance of CSR disclosure in the period before and after the announcement of the CSR directive. Second, we examine how the institutional environment may influence the incremental value-relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosure. In line with previous studies, with respect to the institutional environment we focus on the level of CSR awareness, the level of employee protection, the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment.

For our analysis we use a sample of firms listed on the STOXX Europe 600 index and draw on data covering the reporting period 2008–2016. Our results reveal that for each CSR topic, the information companies disclose is value-relevant. However, the coefficients vary depending on the regulatory setting. In the period preceding the announcement of the CSR directive the relationship between CSR disclosure and share price is positive and significant for specific topics of CSR; namely, social matters, human rights, corruption and bribery. In the period following the announcement of the CSR directive, this relationship is negative and significant across the board.

With regard to the impact of the institutional environment, our evidence shows that the institutional environment does influence the incremental value-relevance of individual CSR topics. Specifically, we find that the relationship between the level of CSR awareness within a country as a whole and CSR disclosure is negative and significant with regard to all CSR topics. This suggests that in countries where CSR awareness is relatively high, the value-relevance of CSR disclosure is limited; much the same applies to the level of employee protection.

In contrast, our results show that the relationship of both the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment with a firm’s value is positive with regard to specific CSR topics: in the case of the degree of enforcement, this relationship is positive and significant with regard to environmental matters, social matters, employee matters and human rights, while this relationship is positive and significant with regard to human rights, corruption and bribery, for the strength of the legal environment.

To check the robustness of our findings, we ran a battery of tests. First, we ran analyses with additional control variables, including the issuance of a standalone CSR report, a firm’s CSR performance and financial characteristics. Our results remain largely unchanged and reveal that the issuance of a CSR report is not associated with firm value while CSR performance is positively associated. Second, we reran our analysis on diverse sample splits and revealed that our findings do not hold in the case of environmentally sensitive industries. Third, we examined whether the textual characteristics of CSR reports, such as readability and tone, affect our results and found that our results remain robust also in this case. Finally, we also examined the impact of an aggregated institutional factor and found a negative and significant relationship between this factor and the incremental value-relevance of CSR disclosures which is consistent with Cahan et al. (Citation2016).

This paper contributes to the literature in a number of ways. First, in contrast to much of the recent literature, which concentrates on the impact of one or two highly aggregated institutional factors (Cahan et al., Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012, Citation2014) on the value relevance of CSR disclosure and provides mixed findings, we identify and examine four distinct such factors that comprise 20 institutional variables. Our results reveal that there are differences in how each factor influences the incremental value-relevance of CSR disclosure and therefore help clarify the mixed conclusions drawn from previous evidence.

Second, to the best of our knowledge, our paper is among the first to investigate the value relevance of CSR disclosure with regard to specific topics of CSR. Previous studies, with few exceptions (Bernardi and Stark (Citation2018); Ioannou and Serafeim (Citation2017) and Cannon et al. (Citation2020)), tend to examine CSR disclosure on an aggregated level. Our topic-specific analysis, however, shows that there are differences in the significance and strength of these associations depending on the distinct CSR topic. Additionally, because the CSR directive on which we focus is not industry-specific but has a broad range of users, our findings can be generalized across various industries.

Third, textual analysis enables us to overcome some of the weaknesses of previous studies, particularly the use of aggregated (often proprietary) or manually obtained CSR disclosure scores. Textual analysis is performed by algorithms and is therefore largely independent of subjective judgments; furthermore, other researchers can use the word lists we have compiled (which cover the six topics of CSR that the CSR directive covers) and easily carry out textual analysis of different samples.

Finally, we are among the first to exploit the unique research setting that the introduction of the EU-wide CSR directive has created through the shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting on a supranational level. Following prior evidence about firms’ anticipatory effects on CSR activities (Fiechter et al., Citation2019) we focus on this regulation-driven shock and investigate the relationship between CSR disclosure and firm value before and after the announcement of the CSR directive. In addition to our theoretical contributions, our empirical findings can help practitioners understand better how CSR disclosure with regard to specific CSR dimensions can affect capital markets. Overall, our findings show that since the CSR directive became law, CSR disclosure has become negatively related to share price and that in countries with high levels of CSR awareness and employee protection, CSR reporting with respect to specific topics has less additional impact on share price. With respect to further disclosure regulation for small and medium-sized companies (SMEs), our findings show that despite uniform standards across the EU, different aspects of the institutional environment may influence how actors in capital markets interpret informational content that concerns specific CSR dimensions.

In the next section, we present the institutional background of the CSR directive and review the literature. We then discuss the theoretical background of our paper and develop our hypotheses. Following that, we discuss our empirical model, sampling procedure and the measures we use in our model and we present our descriptive and multivariate results, as well as insights from additional robustness tests. We conclude our paper with an overview of our main findings.

2. Institutional background and prior literature

2.1. The EU CSR directive

It was only in April 2014 that the European Union passed a directive mandating the ‘disclosures of non-financial and diversity information’ for large companies (i.e. public interest entities with over 500 employees), with effect from all financial years starting on 1 January 2017 onwards (CSR Directive Article 1, 19a (1) [1]). The directive was aimed specifically at firms that are listed on EU exchanges or that carry out extensive operations within the EU. These companies are defined as large or public-interest entities (PIEs) on the basis of their activities, size or number of employees.Footnote1 The CSR directive states that companies are obliged to include in their annual management report a non-financial statement on the impact of their ‘development, performance, position’ and activities on ‘environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters’. In certain circumstances, companies can publish this non-financial report as a separate document (CSR Directive Article 1, 19a (1) [4]). The purpose of publishing such non-financial information is to help a range of stakeholders assess the environmental and social impact of large companies, encourage these companies to act responsibly, foster robust growth and employment and increase trust among stakeholders, including investors and consumers.Footnote2 However, the directive does not require companies to apply a specific, standardized CSR framework or member states to demand that the CSR reports be verified by an assurance auditor: companies may prepare their statements on the basis of any internationally recognized standard-frameworks, such as the UN Global Compact, and it suffices for an auditor to confirm that they have published the mandatory report. Although the considerable flexibility of the directive’s guidelines has attracted criticism, at the same time, the publication of the directive is regarded as a milestone in signaling the importance of sustainability for and within the EU.

This shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting across the EU has profound implications for all EU member states. The scope of this exogenous regulation-driven shock represents a unique research setting that allows us to investigate how this mandate shapes the relationship between firm value and CSR disclosure in diverse institutional environments. To date, the literature on CSR disclosure has largely focused on voluntary disclosure within specific national jurisdictions or on mandatory disclosure within specific countries or industries – for example, Barth et al. (Citation2017), South Africa and Chen et al. (Citation2018), China and specific industries. In our study, we exploit the time lag between the announcement of the EU directive in 2014 and the first release of mandatory CSR information for the financial year 2017 disclosed in 2018. This allows us to investigate the shift from voluntary to mandatory disclosure, especially considering how companies may have prepared in anticipation of this shift. Previous research provides evidence that many companies that are affected by the directive anticipated this shift by increasing their CSR activities before the EU mandate came into effect (Fiechter et al., Citation2019).

2.2. Prior literature

We organize the literature on the value-relevance of CSR disclosure that we review here in two streams: the first stream focuses on the value-relevance of CSR disclosure, while the second stream focuses on how the institutional environment affects the value-relevance of CSR disclosure. The majority of studies examine voluntary CSR disclosure, as the shift to mandatory disclosure took place relatively recently.

Although the evidence of the literature is mixed, most studies indicate that CSR disclosure tends to increase a company’s value. This group of studies includes Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2011), Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012), Clarkson et al. (Citation2013) and Plumlee et al. (Citation2015). Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2011), for example, established a link between CSR reporting and the cost of equity capital: in their sample of US firms, those with higher costs of equity were more likely to release a separate CSR report and first-time reporters could decrease their cost of equity capital in subsequent years. In a subsequent study based on a worldwide sample, Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012) found evidence that the publication of a stand-alone CSR report improved the accuracy of earnings forecasts. Other studies examine environmental disclosure. For instance, Clarkson et al. (Citation2013) found a positive association between environmental disclosure and firm value (share price); and Plumlee et al. (Citation2015) found a positive association between environmental disclosure and expected future cash flows.

In contrast to this body of research, other studies have found either no relationship or a negative relationship between voluntary CSR disclosure and firm value. For example, Richardson and Welker (Citation2001) examined social disclosure, using a sample of 124 Canadian firms. The evidence from their three-year study shows a positive relationship between social disclosure and cost of capital, which suggests that CSR disclosure decreases firm value. Likewise, Cho et al. (Citation2015), whose data cover 418 US industrial firms during reporting years 1978 and 2010, found no significant relationship between either CSR disclosure or social disclosure and firm value, but detected a negative relationship between environmental disclosure and firm value.

Mandatory CSR disclosure started becoming more widespread relatively recently, so the relevant studies are also more recent. Using data on four countries, Ioannou and Serafeim (Citation2017) found a positive and significant relationship between firm value and the overall Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score and between firm value and the separate environmental, social and governance disclosure scores. Barth et al. (Citation2017) examined the relationship between the reporting quality of mandatory integrated reports and firm value in South Africa. Their results reveal positive and significant associations between the quality of integrated reports and firm value. Chen et al. (Citation2018) examined the introduction of mandatory CSR reporting for firms listed on certain stock exchanges in China. Using a sample of 3120 firm–year observations (comprising 1643 observations for treated firms), Chen et al. (Citation2018) found that once CSR reporting became mandatory, the profitability of firms affected by the regulations decreased compared to the control group. Manchiraju and Rajgopal (Citation2017), who studied the introduction of a CSR expenditure mandate in India found similar results. In their study, the mandated CSR investments influenced firm value negatively (as measured by Tobin’s Q).

The second stream of studies we review concentrates on how the institutional environment may affect the value-relevance of CSR disclosure. Financial disclosure has been extensively studied to date (Burgstahler et al., Citation2006; Core et al., Citation2015; Francis et al., Citation2008; Gaio, Citation2010; Hail & Leuz, Citation2006; Isidro & Marques, Citation2015; Leuz et al., Citation2003; Wang & Yu, Citation2015). In contrast, research on CSR disclosure is nascent and comprises only a handful of studies (Barth et al., Citation2017; De Villiers & Marques, Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012, Citation2014).

Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012) used a sample of 7108 firm–year observations covering the period 1994–2007 to investigate in what type of institutional setting CSR disclosure may improve the accuracy of analysts’ forecasts. The authors found that the association between the publication of a stand-alone CSR report and lower earnings forecast errors is more pronounced for countries that are more stakeholder-oriented and for companies with greater opacity in their financial disclosure. Considering the same cross-country setting, Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2014) also observed the same phenomenon with regard to the cost of capital in a similar setting.

More recently, Cahan et al. (Citation2016) examined the relationship between overall CSR disclosure and firm value using a sample of 676 firms in 21 countries for the year 2008. The authors employed a proprietary CSR disclosure proxy provided by KPMG. The authors’ results reveal that CSR disclosure is significantly and positively associated with a stronger national institutional setting. Furthermore, they found a positive association between firm value, as measured by Tobin’s Q, and CSR disclosure only for the unexpected and not the expected part of the disclosure. This relationship is weaker in countries with stronger institutional settings, which contradicts the findings of Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2014) and Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012).

De Villiers and Marques (Citation2016) also found a positive relationship between the level of CSR disclosure and the strength of the institutional environment in a sample of 366 European firms. The authors used data on the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) reporting level, covering a period of four years, and noted a positive and significant association between CSR disclosure and share price. Their study shows that this relationship is more pronounced in countries with stronger governance mechanisms – in contrast to the findings of Cahan et al. (Citation2016).

Overall, the literature indicates that CSR disclosure does provide useful information to the market. However, the differences in the focus, settings and the means various studies have used so far to measure CSR disclosure make it impossible to draw definitive conclusions. Moreover, it is possible that the existing evidence for a link between voluntary CSR disclosure and firm value may be influenced by mediating factors and the ‘dual selection bias’ (Christensen et al., Citation2019). There is some research on the potential role of mediating factors in the context of the institutional environment (Cahan et al., Citation2016; De Villiers & Marques, Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012, Citation2014), but the empirical evidence on the direction of the effect the institutional environment may have on the value-relevance of CSR disclosure is still mixed.

3. Empirical predictions and hypotheses

3.1. The value-relevance of CSR disclosure

From the economic perspective, two contrasting views on the link between CSR activities and firm value prevail. The ‘shareholder expense view’ (Friedman, Citation1970) posits that the effect of CSR activities on a firm’s value is negative, because CSR activities cater to stakeholders at the expense of shareholders. The ‘stakeholder maximization view,’ on the other hand, posits that strategic CSR activities can increase firm value (Deng et al., Citation2013). In line with contract theory and the theory of the firm (Coase, Citation1937),Footnote3 the ‘stakeholder maximization’ approach premises that focusing on the interests of different stakeholders increases their willingness to support the firm’s operations and therefore benefits the shareholders too.

Considering the differences between these views, as Christensen et al. (Citation2019) concluded, it is not surprising that the literature on the relationship between CSR activities and firm value has produced mixed results.Footnote4 Because CSR activities are reflected in CSR disclosure, capital market participants should be concerned with CSR disclosure. Although the relationship between CSR disclosure and firm value is neither theoretically nor empirically clear, the potential of CSR disclosure to impact firm value is uncontroversial.

In addition to these theoretical elaborations on the relationship between CSR activities and firm value, another reason for the inconclusive evidence on the relationship between CSR disclosure and firm value is that the financial effects of CSR disclosure are not as easy to predict as the effects of financial disclosure. The latter has been widely studied and the general theoretical and empirical consensus (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001; Leuz & Verrecchia, Citation2000; Leuz & Wysocki, Citation2016) is that the more financial information a company discloses voluntarily, the more positive the impact of that information on the company’s value.Footnote5

Financial disclosure and CSR disclosure also differ with regard to whether they are mandatory or not, the homogeneity of the audience, the aspects they relate to and the functions they serve (Christensen et al., Citation2019). For instance, CSR disclosure is less regulated than financial disclosure and often not subject to a mandatory audit. In addition, the users of disclosed CSR information are more diverse in their backgrounds and interests compared to the users of financial information. As a result of this diversity, the motives for disclosing CSR information voluntarily are relatively broad and include the desire to improve a firm’s value but also the need to build employee loyalty, customer loyalty and the firm’s reputation.

Therefore, studying it requires us to draw on both economic as well as socio-political theories, in particular legitimacy theory. Legitimacy theory argues that firms disclose information on their CSR activities in order to maintain corporate legitimacy among a broad group of stakeholders (e.g. Deegan, Citation2002); however, such information is typically not value-relevant.Footnote6 Although several empirical studies provide evidence that voluntary CSR disclosure has a positive effect on firm value (e.g. Clarkson et al., Citation2013; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2014; Gao et al., Citation2015), these studies typically suffer from the ‘dual selection problem’ Christensen et al. (Citation2019) has described: in a voluntary setting, firms can (1) choose their CSR activities and (2) base their CSR disclosure on cost–benefit considerations.

This dual selection problem is less present in a mandatory setting, where all firms, irrespective of their CSR performance and reputation, have to disclose their CSR activities. One might expect that, on the whole, the switch from voluntary to mandatory disclosure is negatively associated with firm value, because most of the firms that will be obliged to publish a CSR disclosure following this change will be those that had chosen to withhold such information while its disclosure was still voluntary. Some of the expected negative effects might result from the actions some companies will take to manage disclosure, especially when the CSR disclosure does not reflect accurately the extent of their actual efforts to improve CSR (Dranove & Jin, Citation2010). Furthermore, making CSR disclosure mandatory may level the playing field and prevent companies with a good CSR performance from standing out among companies that perform poorly in terms of CSR. A further reason for expecting a negative association between CSR disclosure and firm value is the cost of CSR disclosure (Christensen et al., Citation2019).

However, all those theoretical discourses have in common, that they regard CSR as a whole and do not consider the distinct topics it is composed of. This, however ignores growing, mostly empirical, evidence about differences in how companies report on different CSR topics. Dorfleitner et al. (Citation2015) suggested that although overall ESG or KLD values may be positively related to financial performance, the real effect of CSR activities on financial performance depends on the importance of the theme behind the considered company and the relevant cost. Accordingly, previous research on CSR disclosure provides inconclusive evidence on whether the effect of specific topics of CSR on firm value is positive or negative, but there is some evidence that the size of the effect may vary depending on which CSR topics a disclosure concerns (Bernardi & Stark, Citation2018).

In sum, whether CSR disclosure, broken down into its respective topics, is positively or negatively associated with firm value is an empirical question, which we address in this study. Our study is among the first to simultaneously examine different topics of CSR disclosure and to apply textual analysis for that purpose.Footnote7 To design our CSR disclosure measure, which targets topic-specific CSR disclosure, we used the annual reports of firms.Footnote8 We took into account the six topics of CSR that the CSR directive addresses and we constructed four thematic groups: (a) environmental matters, (b) social and employee matters, (c) respect for human rights and (d) anti-corruption and bribery matters. On that basis, we formally posit the following undirectional hypothesis:

H1: A company’s annual disclosure on

(a) environmental matters

(b) social and employee matters

(c) human rights matters

(d) anti-corruption and bribery matters

provides information to capital-market participants that is in addition to the financial information the company publishes.

3.2. The role of the institutional environment

There is extensive empirical evidence that the potential economic consequences of firm disclosure vary considerably depending on the institutional environment (Hail & Leuz, Citation2006; Hope, Citation2003; Leuz et al., Citation2003; Wang & Yu, Citation2015). In that respect Christensen et al. (Citation2019) argue that it is not one particular institutional factor, but a ‘fit’ between different institutional factors that influences the consequences of CSR disclosure. We therefore focus on four institutional factors; namely, the level of CSR awareness, the level of employee protection, the strength of the legal environment and the extent to which regulations are enforced; we consider all four factors on a country-level.

With respect to CSR awareness and employee protection, the literature shows that there is significant variation in voluntary CSR disclosure across different countries (Chen & Bouvain, Citation2009; Fifka, Citation2013; Kolk & Perego, Citation2010; Maignan & Ralston, Citation2002; Orij, Citation2010; Van der Laan Smith et al., Citation2005). What is less clear is what direction the relationship between specific CSR-related institutional factors and the value-relevance of CSR disclosure may take. The relevant empirical evidence and theoretical predictions are mixed.

From a theoretical viewpoint, on the one hand, one may argue that in countries characterized by strong CSR awareness and a high degree of employee protection, the information CSR disclosure contains is more credible, because stakeholders are able to better monitor a company’s CSR activities. Thus, CSR disclosure in such countries is more value-relevant (see Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012, Citation2014). On the other hand, one may also argue that in such countries, i.e. with a stronger institutional environment, the value-relevance of CSR disclosure is weaker. This argument relies on the ‘national business systems’ approach (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001; Maurice et al., Citation1980; Maurice & Sorge, Citation2000). According to the rationale of Matten and Moon (Citation2008), stronger CSR regulation might decrease the value-relevance of CSR disclosure because CSR disclosure is more implicit. Cahan et al. (Citation2016) found evidence for this kind of negative relationship; however, it should be noted that the authors used an aggregate measure of institutional strength. On the basis of the mixed theoretical predictions and empirical evidence, we posit a non-directional hypothesis on how the two specific aspects of CSR we discuss above – namely, CSR awareness and employee protection – influence the strength of the value-relevance of CSR disclosure:

H2: The level of

(a) CSR awareness

(b) employee protection

in a particular country has either a positive or a negative impact on the incremental value-relevance of CSR disclosure.

H3: The

(a) degree of enforcement and

(b) strength of the legal environment

of the respective country have either a positive or a negative impact on the incremental value relevance of CSR disclosure.

4. Research design and variables

4.1. Empirical model

To assess how the institutional environment shapes the incremental value-relevance of disclosure on specific topics of CSR in a company’s annual report, we began by selecting the CSR topics that provide significant information to the capital market based on the CSR directive. We refer to these as ‘topic-specific CSR disclosures’ hereafter. First, we applied a traditional value-relevance model based on Ohlson (Citation1995). Specifically, we ran the following nested panel regressions with fixed effects for cross-sections and years, using fiscal-year-end data:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

Here, P denotes the share price of a certain company, BVE is the book value per share and EARN stands for the earnings per share.

is a proxy for topic-specific CSR information in the annual report; namely, information on the environment (TENV), social matters (TSOC), employee matters (TEMPL), human rights (THR), corruption (TCORR) and bribery (TBRIB).Footnote9 To control for the effects of the issuance and implementation of the CSR directive, from which we extracted the specific ‘topics,’ we took into account the findings of Fiechter et al. (Citation2019) and Grewal et al. (Citation2019) on the anticipatory effects of the CSR directive and we included interaction terms of topic-specific CSR disclosure with POST. Here, POST is a proxy for the shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting and denotes the announcement of the CSR directive in 2014: it amounts to 1 for the years 2014, 2015 and 2016 and 0 otherwise.Footnote10 We provide a list of all our variables in Appendix I.

Next, we calculate as follows the change in the explanatory power of the nested panel regressions incremental to the addition of topic-specific CSR disclosure: . Here,

is the adjusted

of the baseline model (1) and

is the adjusted

after we added the topic-specific CSR disclosures

to the pooled regression model; both were calculated at the firm level.Footnote11 The advantage of this comparison is that each adjusted

reflects the explanatory power of the respective topic-specific CSR disclosure for the dependent variable; this enables us to consider the incremental information content provided on the stock price, P, by the respective CSR disclosures (Barth et al., Citation2012). We then checked whether the institutional environment significantly influences the change in the explanatory power as a result of the additional topic-specific CSR disclosures

. To do so, we ran the following regression model with country fixed effects and industry fixed effects:

(3)

(3)

Here, factor_csr, factor_empl, factor_enfand factor_legal are the factors we derived from running a factor analysis and using proxies for the level of CSR awareness and of employee protection, the strength of the legal environment and the degree of enforcement (see 4.4). We provide further analyses in Section 6.

4.2. Sampling

We sampled firms listed in the STOXX Europe 600 index as of October 2016. To compile our unique dataset, we collected manually 5023 annual reports for the period 2008–2016.

Panel A of Table provides an overview of the sample-selection process. In total, we obtained 5023 firm–year observations covering 9 reporting years for a sample of 600 firms. We had to exclude from the textual analysis 850 of the reports for various reasons; this reduced our dataset to 4173 observations.Footnote12 Another 212 observations that were incomplete with regard to the dependent variables were also excluded, which reduced our final sample to a total of 3961 observations for equations (1) and (2). For equation (3), we also eliminated instances that did not meet our minimum requirement of 8 observations per firm; for this equation, the sample was therefore reduced to 3303 observations. The distribution of our sample by industry group, which is based on Fama and French (Citation2017) is presented in Panel B, whereas Panel C displays the distribution of the same sample by country.

Table 1. Selection and distribution of our sample.

4.3. Topic-specific CSR disclosure measures

To generate a CSR disclosure measure with respect to different CSR topics, we used textual analysis. Textual analysis as a tool for assessing CSR disclosure has become more widespread in the last decade (e.g. Cannon et al., Citation2020; Cho et al., Citation2010; Hummel et al., Citation2019; Loughran et al., Citation2009; Melloni et al., Citation2017; Muslu et al., Citation2016; Nazari et al., Citation2017). However, only a few studies assess topic-specific CSR disclosure, i.e. disclosure on specific topics of CSR (Cannon et al., Citation2020; Hummel et al., Citation2019; Loughran et al., Citation2009; Pencle & Mălăescu, Citation2016). Several methodological approaches exist for the textual analysis of topic-specific CSR disclosureFootnote13; we apply the procedure introduced by Hoberg and Maksimovic (Citation2015) and Hummel et al. (Citation2019), which relies on topic-specific vocabularies generated from a multitude of reports and use cosine similarity to measure how close the reports are with these vocabularies.

Specifically, we measure the similarity of each annual report and the CSR topics defined by the CSR directive. Following this procedure, we were able to measure to what extent every report in our sample covers each of the following six topics: ‘environment,’ ‘social matters,’ ‘employee matters,’ ‘human rights,’ ‘anti-corruption’ and ‘bribery.’Footnote14 We then defined a search term that directly relates to each of these topics: ‘ecology’Footnote15 for environmental matters (TENV), ‘social’ for social matters (TSOC), ‘employee’ for employee matters (TEMPL), ‘human right’ for human rights (THR), ‘corruption’ for anti-corruption (TCORR) and ‘bribery’ for bribery (TBRIB). In order to do so, we constructed twenty-word windows that comprise the nine words directly before and the ten words directly after the respective search term, resulting in a multitude of 20-word excerpts with the topic-specific search term in the middle.Footnote16 We collected all these word-windows that appear in the annual reports in our sample and aggregated them into topic-specific vocabularies. For this purpose, we used a common weighting term, ‘term frequency inverse document frequency’ (tf-idf) (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2011, p. 1208, Citation2016). We then calculated the cosine similarity between the text in each annual report and the topic vocabularies to measure the degree to which the vocabulary in each report is close to each topic-specific vocabulary. The cosine similarity is a comparison of relative word frequencies that helps identify similarities between pairs of documents (Crossno et al., Citation2011) and is calculated as the inner product of two vectors; one represents the word usage in the annual report and the other represents the word usage in the topic-specific vocabulary. The score ranges between 0 and 1: if the score is 1, the documents have identical proportions of specific words, and if the score is 0, the documents have no similarities (Lang & Stice-Lawrence, Citation2015, p. 113, 131). Consequently, the higher the value of the topic-specific disclosure measure, the greater the similarity between a particular annual report and the topic-specific vocabulary.

Panel A of Appendix II provides an overview of the top twenty words in the twenty-word windows we collected and indicates whether each of these word windows captures accurately the respective topics.Footnote17 On the basis of word frequency, we see that the topic-specific CSR disclosure measure reflecting employee matters (TEMPL) is the most prevalent in the annual reports of the sample firms. This measure appears to capture mainly employee-related issues and the composition of the management and board. The measure reflecting social matters (TSOC) is also prevalent in the annual reports of the sample firms; this measure appears to capture a company’s social responsibility. The frequencies of the sets of words we collected on human rights (THR) and corruption (TCORR) are rather similar. The measure THR appears to capture the discussion of principles and policies related to human rights, both within the firm and in the supply chain. There is considerable overlap in the content that the measures TCORR and TBRIB capture; overall, however, the search term ‘corruption’ occurs much more frequently (18,136) in the annual reports than the search term ‘bribery’ (7334). Both measures reflect the risks, policies, practices (including employee training) and codes of conduct that relate to bribery and corruption. The least frequent topic is ecology (TENV), which relates to environmental issues and sustainable development.Footnote18 Taken together, the words we retrieved from the annual reports indicate that the topic vocabulary captures adequately the predefined topics. In Panel B we provide some examples of the twenty-word windows we describe further up, while in Appendix III we describe in more detail how we calculated the topic-specific disclosure measures.

4.4. Institutional environment

To measure the institutional environment, we complemented the variables used in prior studies (Cahan et al., Citation2016; De Villiers & Marques, Citation2016; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2011, Citation2014; Ernstberger et al., Citation2008; Isidro & Marques, Citation2015; Leuz et al., Citation2003; Wang & Yu, Citation2015) with our own and built a set of 20 institutional variables (see Panel A, in Appendix IV).Footnote19 These 20 variables make up the four institutional factors we identified; namely, the level of CSR awareness, the level of employee protection, the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment. To identify the relevant variables and assess how they are related to these four factors, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) with oblique Oblimin rotations.Footnote20 Panel B in Appendix IV lists the four institutional factors and the corresponding institutional variables (based on the results of the PCA).Footnote21

The first factor (factor_csr) comprises three institutional variables that serve as proxies for the importance of sustainability (Sust_Dev), ethical practices (Eth_Pract) and social responsibility (Soc_Resp) and adherence to environmental laws (Env_Laws). We use these variables to measure CSR awareness. The second factor measures employee protection (factor_empl) and comprises three variables measuring the strength of employee protection laws (Empl_Law), collective relations (Coll_Law) and control of self-dealing (ASDI). The third factor (factor_enf) is measured on the basis of the stability of a country’s government (Gov_Stab) and the degree of public enforcement (PEI) and serves as a proxy for the degree of enforcement. All remaining variables constitute the fourth factor (factor_legal). Most of these variables capture aspects of the legal environment such as the rule of law (Rule_Law), the effectiveness of the government (Govt_Eff), the quality of the relevant regulations (Reg_Qual), the strength of the legal system (Law_Order), democracy (Voice_Acct), corruption control (Corr_Contr), the existence of social security laws (SoSec_Law) and human rights protection (HRI), the degree of journalistic freedom (Jour_Free) and the environment performance index (EPI).Footnote22 We use these variables to measure the overall strength of the legal environment.

In section 6.4, we additionally examine institutional variables derived from the Hofstede database.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive statistics

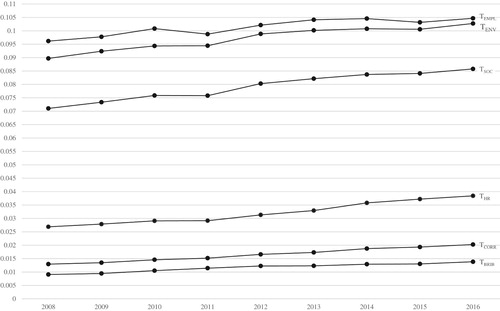

In Table we report the descriptive statistics on the variables used in equations (1) and (2). At the first stage, our dataset comprised 3961 observations. The average value of P is 42 EUR, while BVE yields a mean of 22.11 EUR. Overall, EPS ranges from 0 to 43.46 EUR, with a mean value of 2.41. The mean values of the textual variables vary between 0.01 and 0.1, while the scores of the variables that reflect environmental, social and employee matters display the highest similarity.Footnote23 In Figure we provide some evidence about the yearly evolution of each topic-specific CSR disclosure; the pattern of a yearly increase in CSR disclosures is evident.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for all variables.

5.2. Results on the value relevance of CSR disclosure

Table shows the results of equations (1) and (2), where we regress price on the book value of equity per share and earnings per share; it also shows the results we obtained from applying the respective topic-specific CSR disclosure measures T for the period before and after the announcement of the CSR directive.Footnote24 Our results show that although all textual variables convey new information to the market, the direction of the relationship depends on the observation period and the strength of the association varies depending on the topics.

Table 3. The results of equations (1) and (2): nested price panel regressions Price is regressed on book value of equity and earnings, both per share and on the respective CSR disclosure measures Ti.

In the period before the announcement of the CSR directive, only TSOC (‘social matters’) THR (‘human rights’) and TCORR (‘corruption’) show a significant and positive association with firm value, measured by the share price of the company. With respect to the topics environment, employee matters and bribery, our results indicate that their association with firm value is again positive, but insignificant. After the shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting, the associations between CSR disclosure and share price flip and become negative and significant with respect to all topic-specific disclosures except for that on human rights (as indicated by ).Footnote25

Taken together, our results support H1(a), H1(b), H1(c) and H1(d), which postulate that topic-specific CSR disclosures provide significant information to capital-market participants.Footnote26 The regression models show that the coefficients for disclosure on human rights and corruption (environment and employee matters) are the largest (smallest) in the voluntary setting, while the coefficients for disclosure on corruption and bribery (social and human rights) are the largest (smallest) in the mandatory setting. This result probably reflects the mean prevalence of certain topics in the annual reports, which is considerably lower with regard to human rights, corruption and bribery compared to other topics (see also Table and Figure ). Consequently, an increase in disclosure on these less prevalent topics will have a stronger impact on share price compared to the same increase in disclosure on more prevalent topics. In line with prior literature, the coefficient on BVE is approximately 0.95 and 2.7 for EARN; also, the adjusted R2 of approximately 95% is consistent with the literature on value-relevance (De Villiers & Marques, Citation2016; Hung & Subramanyam, Citation2007).

Our results show that the effect of CSR disclosure depends not only on the topic – that is, on the aspect of CSR on which a company reports its activity – but also on the regulatory setting. What becomes clear from our analysis is that as soon as the European Union announced the CSR directive in 2014, companies anticipated the later implementation of mandatory disclosure by changing their reporting behavior. Before 2014, managers could choose what information to disclose and, typically, they provided information on the company’s CSR activities only if the marginal benefits of disclosure exceeded the marginal costs (Verrecchia, Citation1983). The positive coefficients are in line with prior studies on value-relevance in a purely voluntary setting, which found a positive relationship between CSR disclosure and firm-value (Cahan et al., Citation2016; Clarkson et al., Citation2013; Dhaliwal et al., Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2014; Plumlee et al., Citation2015). In a voluntary setting, however, the positive coefficients may only reflect the ‘dual selection bias’ Christensen et al. (Citation2019) warns about.

As our analysis shows, the shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR reporting flipped the relationship between CSR disclosure and firm value: the association between topic-specific CSR disclosures and firm value became negative. One potential reason for this change could be that in a mandatory setting the ‘dual selection bias’ disappears. Another reason might be that mandatory CSR disclosure entails new direct or indirect costs, such as introducing certain CSR policies and preparing the CSR report. In view of such costs, capital-market participants might adjust their evaluation of companies that are subject to the CSR directive and will therefore be burdened with these costs. A further possible reason might be that the CSR directive is very vague on the frameworks that companies may choose to apply in their reporting and does not mandate the assurance of CSR reports.

5.3. Results on the role of the institutional environment

The descriptive results on the incremental value-relevance of each topic, based on the pooled regressions of equations (1) and (2), are presented in Table .Footnote27 Column one lists the descriptive results (i.e. mean, standard deviation and median) for the adjusted R2 of the base model (i.e. equation 1), while the remaining columns display the adjusted R2 of the nested models, including the disclosure measures for the respective CSR topics. In our sample of 374 firms, the average R2 for the base model is 49.43%, while the incremental R2 on average amounts to 62%. Consequently, including topic-specific CSR measures increases the mean adjusted R2 of the base model, which indicates that topic-specific CSR disclosures are incrementally value-relevant.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the R2 of pooled equations (1) and (2) on the firm level.

To examine how the institutional environment shapes the incremental value-relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosures, we used the values in Table . Table reveals a negative and significant relationship between the incremental value-relevance provided by the textual measures and factor_csr, which reflects a country’s level of CSR awareness, and factor_empl, which reflects the level of employee protection. However, our results show a positive and significant coefficient only for some topic-specific CSR disclosures with regard to factor_enf, which reflects the strength of a country’s enforcement, and factor_legal, which reflects the strength of a country’s legal environment. All these results support H2(a) and H2(b) as well as H3(a) and H3(b).

Table 5. The results of equation (3): the incremental value-relevance of the institutional environment In columns (I) we regress R2 inc(Ti) on the institutional factors, controlling for industry and country-fixed effects; in columns (II) we also add financial characteristics including size, leverage and profitability.

The relationship between the incremental value-relevance and factor_csr, which reflects a country’s level of CSR awareness, as well as factor_empl, which reflects country’s level of employee protection, is negative for every topic-specific CSR disclosure. This means that if managers perceive that a country generally promotes sustainable development, through for instance ethical practices, socially responsible business leaders and decent environmental regulation, the incremental value-relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosures will be relatively low. In other words, strong compliance with CSR and a high degree of employee protection on the country level reduce the incremental value-relevance, and thus the importance, of supplementary information for capital-market participants with respect to all the underlying topics. This finding also supports the reasoning of Matten and Moon (Citation2008), specifically their ‘implicit-explicit’ framework: if CSR awareness and employee protection are important on the country level, companies do not need to address these topics explicitly in their CSR reports, so their incremental value-relevance is limited. In such cases, companies cannot differentiate themselves from other companies through disclosure, and thus, may report implicitly. This finding might be of interest to both, standard-setters who consider the introduction of mandatory CSR disclosure and standard-setters extending an existing CSR mandate on a broader scale.

The coefficients indicate that the size of the effect depends on the CSR topic that a report addresses. With regard to CSR awareness there is modest variation, as the coefficients range from −0.16 in the case of environmental issues to −0.24 in the case of social matters. With regard to the level of employee protection, the effect is smaller in the case of human rights, corruption and bribery, ranging from −0.16 to −0.13, than in the case of environmental issues, social issues and employee matters, where the coefficients range from −0.33 to −0.24.

The factor that reflects the degree of enforcement, factor_enf, is positive with regard to environmental issues, social and employee matters, human rights and bribery, but does not impact the incremental value-relevance of corruption. Thus, it appears that the degree of enforcement is more important for those topics with more prevalent CSR disclosure (see Figure ), i.e. with higher similarity scores. Also, the size of the coefficients varies depending on the topics: it is above 1 in the case of environmental, social and employee matters and below 0 in the case of human rights and bribery. Similarly, we find a positive and significant relationship between the incremental value-relevance of adding topic-specific CSR disclosure and factor_legal for certain topics. Specifically we provide evidence that in countries with a strong legal environment the explanatory power of topic-specific CSR disclosure on human rights, corruption and bribery increases. Bearing in mind that human rights, corruption and bribery exhibit the lowest similarity scores (see Figure ), this result provides interesting evidence that legal institutions can increase considerably the explanatory power of information on CSR topics that are not commonly addressed on a national level. In contrast, our results indicate that the strength of the legal system does not increase the value-relevance of CSR disclosure on environmental issues, social issues and employee matters. Our findings on the factors factor_enf and factor_legal are generally in line with those of Wang and Yu (Citation2015), but contradict those of Core et al. (Citation2015) and Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012). However, these studies tend to rely on composite measures to capture the institutional environment.

Taken together, our results show that the level of CSR awareness and of employee protection in particular influence significantly the value-relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosures. The higher the prioritization of CSR in general and of employee protection in a country, the lower the incremental value-relevance of disclosed information on these topics. With regard to the degree of enforcement and strength of the legal system, our results indicate the opposite. Specifically, we found that the strength of the legal environment increases the value-relevance of CSR topics that exhibit smaller similarity scores, whereas the level of enforcement has the same effect on CSR topics that exhibit higher scores. Overall, our results show that the value-relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosure is lower in countries characterized by high CSR awareness but higher where regulations are legally enforced. This is not surprising, in light of the criticism that the CSR directive fails to specify a reporting framework and to mandate the assurance of CSR reports.

6. Further Analyses

6.1. Alternative model specifications

In order to provide some robustness checks with respect to Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2011), Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012), and Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2014), we also consider the issuance of a stand-alone CSR report as a proxy for CSR disclosures. We therefore added a new variable to equation (2), CSR_Report, whose value is 1 if the firm publishes a separate CSR report in a particular year and 0 otherwise.Footnote28 This test confirms that our results (untabulated) are in line with Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2011) and Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2012), showing a positive and significant relationship in the baseline model at a 10% significance level. When we take into account both the release of topic-specific CSR disclosures and of a separate CSR report, our main results remain unchanged. However, in this case CSR_Report is not significant. In sum, our results show that the publication of a single CSR report does not allow us to measure the effects of CSR disclosure adequately. As the results we obtained from the topic-specific measures show, to capture those effects accurately, it is necessary to take into account the dimensions of CSR that a disclosure concerns.

Furthermore, the literature shows that CSR performance can also have an impact on CSR disclosures (Al-Tuwaijri et al., Citation2004; Hummel & Schlick, Citation2016). To test the robustness of our findings, we therefore additionally include two alternative measures in equation (2) that reflect a firm’s CSR performance. First, the dummy DJSI that equals 1 if a company is listed in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI); second, a4ir, the ESG score provided by ASSET4 Thomson Reuters, capturing a company’s overall ESG performance. Both of these CSR performance measures are positive and significant (untabulated results) and our results on topic-specific CSR disclosure remain largely unchanged.

To rule out the impact of firm-specific factors on our findings, we repeated the regressions for equation (3) with additional control variables that reflect firm-level characteristics, including firm size (as the logarithm of total revenues), firm profitability (as the return on assets), firm leverage (as the ratio of debt to total assets) and CSR performance (as DJSI and a4ir). We excluded from our samples any observations for which we did not have complete data (see Table ).

Our results remain robust when we take into account firm-level characteristics (see Table ). Leverage is positive and significant with respect to social matters, employee matters and corruption, which indicates that the incremental value-relevance of the information on these topics is higher in the case of highly leveraged firms. Our additional results also show that the size and profitability of a company both have a negative and significant impact on the incremental value-relevance of all CSR topics we include in our model. The larger and more profitable a company, the lower the impact of CSR disclosures on the company’s value. With respect to the CSR directive, this finding is particularly noteworthy, given that the directive concerns only large companies.

Next, we also include a4ir and DJSI in equation (3). This set of results (untabulated) reveals DJSI is positive and significant with respect to all topic-specific CSR disclosures. This suggests that being listed in the DJSI alone increases the explanatory power of a company’s topic-specific CSR disclosures. In contrast, a4ir is not significant with regard to any topic and does not impact the results.

Finally, we reran the pooled regression models (1) and (2), taking into account CSR performance and then reran equation (3) for the newly obtained incremental value relevance measures . Our results for the institutional factors remain largely unchanged. Only for employee matters and human rights does the relationship change significantly; in the case of corruption and bribery, factor_enf is positive and significant if a4ir is included (untabulated results).

6.2. Sample splits

To test whether the sample specification affects any of our results, we performed our analyses on different sample specifications. Previous research has shown that in environmentally sensitive industries (ESI)Footnote29 firms are more likely to release CSR information (Cho et al., Citation2015; Cho & Patten, Citation2007; Stolowy & Paugam, Citation2018). Such firms are under greater public pressure and seek to legitimize their actions by disclosing information on their CSR activities. Cho et al. (Citation2015) argue that this information is not value-relevant. According to this reasoning, our findings should not hold for the sub-sample of firms in environmentally sensitive industries. Indeed, our (untabulated) results reveal that the relationship between CSR disclosure and share price is not significant in the case of firms in such industries, whereas they do hold in the case of firms in other industries.

Recent studies indicate that research on CSR disclosure should also consider the extent to which a firm’s CSR disclosure is aligned with its CSR performance (Cheng et al., Citation2015; De Villiers et al., Citation2019; Guiral et al., Citation2019). Firms with aligned CSR disclosure disclose more (less) CSR information if they have better (worse) CSR performance. De Villiers et al. (Citation2019) show that the positive relationship between (unexpected) CSR disclosure and dividend pay-outs is particularly driven by firms with aligned CSR disclosure. Thus, in our setting, we would expect that poor alignment between a firm’s CSR performance and disclosure reduces the value-relevance of the CSR disclosure and vice versa. Indeed, in the case of firms whose CSR disclosure and performance are aligned, our (untabulated) results remain largely unchanged; in contrast, in the case of firms whose CSR disclosure and performance are not aligned, only disclosures on corruption and bribery show a negative and significant relationship with the firm value after the shift from voluntary to mandatory CSR disclosure.

A further factor that could affect our results is the application of GRI reporting standards that companies use to report on CSR. Our tests did not indicate substantial differences for the sample of firms that apply the GRI reporting standards versus the sample of firms that do not apply the standards.

6.3. Textual analysis

One could argue that the disclosure measures we applied are biased due to the textual characteristics of the reports in our sample. Prior research shows that particularly readability and tone are associated with financial performance and capital market efficiency (Biddle et al., Citation2009; Caglio et al., Citation2020; Chen & Tseng, Citation2020; Huang et al., Citation2014; Lehavy et al., Citation2011; Li, Citation2008; Lo et al., Citation2017; Miller, Citation2010). Readability describes how easily the reader can grasp the content of a text, while tone refers to the overall attitude of a text. The literature typically refers to the Fog Index, the Flesch-Kincaid and the Flesch Reading Ease as typical measures of readability. These measures are calculated on the basis of the average number of words per sentence and the average number of syllables per word. Following De Franco et al. (Citation2015), we created an aggregate measure of readability based on the Fog Index, the Flesch-Kincaid and the Flesch Reading Ease. More precisely, discl_readability is measured by the average of the percentile ranks for each component, divided by 100 and multiplied by (−1). Thus, higher values in discl_readability indicate that a text is particularly readable.

Tone refers to the sentiment of the report, i.e. how positive or negative the text is. To identify positive and negative words in our sample of annual reports and measure their tone, we used the word list provided by Loughran and McDonald (Citation2011). This word list has been specifically designed for accounting research. On that basis, we calculated the measure discl_tone as the frequency of positive words (relative to all words) minus the frequency of negative words (relative to all words) in a report.

Our descriptive statistics show that discl_readability has a mean value of −0.5067, which indicates that all three readability measures listed earlier are consistent on average. The value of the Gunning Fog Index is 13, which shows that, on average, a reader needs to have completed 13 years of education in order to grasp the content of the annual reports. The tone of the annual reports is positive and amounts to 0.0023 on average. In comparison to CSR reports (Hummel et al., Citation2019) and earnings press releases (Huang et al., Citation2017), this value is lower – which makes sense, because annual reports are legal documents and therefore require a more neutral (and less optimistic) language. Compared to 8-K filings, the tone is more positive (Henry & Leone, Citation2016). We reran the regressions for equations (1) to (3), including both tone and readability. Neither measure is significant in equations (1) and (2), and our (untabulated) results remain unchanged. This finding also supports the reasoning that, compared to general textual characteristics, topic-specific measures are more appropriate for our study.

Our results on the incremental value-relevance are displayed in Table : discl_tone is negative and significant in the case of all topics, which indicates that the incremental value-relevance of all topic-specific CSR disclosure is smaller when an annual report is positive in tone. With respect to readability, the relationship is positive and significant only for employee matters and human rights, which indicates that higher readability increases the explanatory power of CSR disclosure on these topics.

Table 6. Results for equation (3): controlling for textual characteristics We regress

on the Institutional Environment and Textual Characteristics of the Annual Report, namely readability and tone, controlling for industry- and country-fixed effects.

on the Institutional Environment and Textual Characteristics of the Annual Report, namely readability and tone, controlling for industry- and country-fixed effects.

To test whether our measurements of topic-specific CSR disclosure were biased because of boilerplate language, we performed two further analyses. First, we calculated the similarity scores for standard boilerplate content (standard_boilerplate) and industry-specific boilerplate content (industry_boilerplate) and included the two variables as additional controls in equation (1). Our (untabulated) results remain unchanged. Second, in order to eliminate industry-related and yearly boilerplate-effects, we calculated an alternative measure of topic-specific CSR disclosure: we regressed the similarity score on the two boilerplate measures and used the resulting residuals as topic-specific disclosure. This procedure purges the topic-specific disclosure measures for boilerplate content. With respect to equation (2), our main results remain robust for β4 and TSOC, TEMPL, THR, TCORR and TBRIB, but become insignificant for β3 (untabulated). Thus, the positive effect we obtained in our main analyses for some of the topic-specific disclosures on share price in the period prior to the announcement of the CSR directive (as indicated by β3) is not robust. Meanwhile, both the negative impact of the shift from a voluntary to a mandatory setting (as indicated by β4) as well as the negative impact of topic-specific disclosures in the period after the announcement of the CSR directive persist (as indicated by β3+β4). We use these boilerplate-adjusted topic-specific disclosure measures to calculate the incremental value-relevance and reran equation (3). The (untabulated) results we obtained for our institutional factors are similar to our main results, both in terms of direction and significance of the effects.

6.4. Institutional variables

For the purposes of our study, we examined the impact of four distinct institutional factors on the value-relevance of CSR disclosure, which enabled us to provide more detailed insights into the effects of different institutional characteristics. Nevertheless, in line with prior studies (e.g. Cahan et al., Citation2016), we also aggregated these four institutional factors to a single factor (factor_inst) to compare our results directly with those of previous research. Like Cahan et al. (Citation2016), we also found that institutional strength has a negative and significant impact on the value-relevance of CSR disclosure (untabulated results).

We also investigated whether the impact of the institutional environment on the incremental value relevance of topic-specific CSR disclosures is different for good versus bad CSR performers. For that purpose, we interacted the aggregated measure of the institutional environment with two dichotomized variables of CSR performance; namely, whether a company is listed in the DJSI (DJSI) and whether a company’s CSR performance is above the median, based on the a4ir score (a4ir_good). Our results (see Table ) show that the coefficients of factor_inst remain negative and significant. Thus, the incremental value relevance of CSR disclosure is weaker when the institutional environment is stronger. Furthermore, the interaction between factor_inst and CSR performance is negative, yet only significant for DJSI. This negative interaction indicates that the negative impact of the institutional environment on the incremental value relevance of CSR disclosure is even more pronounced for good CSR performers.

Table 7. Results of equation (3): the incremental value-relevance of the institutional environment among good and bad CSR performers.

Furthermore, following Hope (Citation2003), we decided to account for the potential impact of national culture. Using the dimensions provided by Hofstede (Citation1983), we reran equation (3) separately for every dimension. Two of these dimensions have a positive and significant relationship with regard to all topics except environmental issues: power of distance, which reflects how a society handles inequalities among people, and individualism, which reflects whether people perceive themselves as ‘I’ or ‘we.’ In contrast, the other two dimensions are negatively related to all topics except environmental issues; namely, masculinity, which measures the level of competitiveness in a society, and the uncertainty avoidance index, which reflects the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. Interestingly, and in line with the results we obtained when examining the impact of an aggregated institutional factor, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, Citation1983) do not appear to have an impact on environmental issues. Our results are broadly in line with Cahan et al. (Citation2016) and Hope (Citation2003), except that their studies suggest that in the case of power of distance the relationship should be negative.

7. Conclusion

This study investigates the value-relevance of the information on specific CSR topics that firms provide in their annual reports and how this might be shaped by the national institutional environment. We applied textual analysis to examine firms’ disclosure in their annual reports on ‘topic-specific’ CSR categories concerning environmental issues, employee matters, social matters, human rights, corruption and bribery. In our textual analysis, we followed the methodology that Hoberg and Maksimovic (Citation2015) and Hummel et al. (Citation2019) introduced and extracted twenty-word ‘windows’ to construct a vocabulary for each CSR topic. We then measured the similarity between each of these topic-specific vocabularies and each report in our sample of 3961 firm–year observations. Our results show that the information firms disclose on the specific topics of CSR are useful for capital market participants.

To analyze the incremental value-relevance of each of the topics required by the CSR directive, we examined how the institutional environment affects the increase in the explanatory power of the respective information – specifically, the adjusted R2. Drawing on the literature, we focus on four institutional factors: the level of CSR awareness, the level of employee protection, the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment. Our results indicate that CSR awareness and employee protection have a negative effect on the explanatory power of disclosed information on corruption and respect for human rights as well as on environmental, social and employee matters. This finding is consistent with the implicit-explicit framework (Matten & Moon, Citation2008) framing that firm report more implicitly about CSR if there is more country-specific regulation with respect to the considered CSR topics. With regard to the degree of enforcement and the strength of the legal environment, we find an indication of an increase in explanatory power for the topics under consideration.

Like all studies, this study also has some limitations. First, we focus on the information that firms disclose on various aspects of CSR in their annual reports; however, it is true that firms may disclose such information also through other channels, such as separate CSR reports on their websites. The additional analyses, which take into account at least one of these alternative channels, show that stand-alone CSR reports are not value-relevant when we include topic-specific CSR disclosures in our model. Nevertheless, future research could examine the combined impact of CSR information that companies disclose both in their annual reports and in stand-alone CSR reports. Such an approach would be particularly appropriate, given the growing trend towards integrated reporting.

Second, this study is an association study and as such does not provide evidence for a causal relationship; we cannot completely rule out the possibility of reverse causality. Indeed, as Lys et al. (Citation2015) have shown, firms that perform well may use CSR disclosure to signal their superior performance. Future studies could select a setting that makes it possible to identify clearly any causal effects. Finally, our study is not free from the usual weaknesses of textual analysis. In particular, our sample consists of reports published by firms located in different European countries. However, in many of these firms English will be used only in business documents and not in other contexts. For that reason, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that translation may have some impact on those documents’ textual characteristics. On the other hand, because we focus mainly on specific topics of CSR the examined reports contain, rather than on the purely textual characteristics of these documents, such as readability and tone, we are confident that our results are not biased by the potential effects of translation. Moreover, the novel methodology we apply in our textual analysis to examine disclosed information on specific topics of CSR may be of interest to other researchers, both in the area of CSR accounting and in other accounting areas. Finally, we acknowledge that the measure we use does not capture the tone of the documents we examined, because it relies on twenty-word windows. The tone of the information companies disclose on CSR may prove an interesting subject to future research.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the 41st annual congress of the European Accounting Association 2018 in Milano, Michael Stich and Stefan Leixnering for their helpful comments and suggestions. We are grateful to the editor Hervé Stolowy and the associate editors Reuven Lehavy and Florin Vasvari. In addition, we are thankful to two anonymous referees for their constructive comments that added significant value to the content of the paper and enhanced the clarity of the exposition. Furthermore, we thank Martin Saurer for his technical support. Finally, we benefited from the valuable research assistance of Dominik Scherrer, Kevin Wagner, Felix Schiff, Dominik Bryndza, Teresa Wagner and Verena Guggenberger.

Notes

1 The requirements for the disclosure of non-financial information apply to large companies with more than 500 employees because in the case of SMEs the cost would outweigh the benefits.

2 Communication from the European Commission, guidelines on non-financial reporting (methodology for reporting non-financial information) 2017/C 215/01, European Commission (Citation2017).

3 See Alchian and Demsetz (Citation1972), Cornell and Shapiro (Citation1987), Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) and Hill and Jones (Citation1992).

4 Orlitzky et al. (Citation2003), Margolis et al. (Citation2009) and Kitzmueller and Shimshack (Citation2012) have all published relevant meta-analyses. Al-Tuwaijri et al. (Citation2004) discuss a number of mediating factors that can impact or even flip the relation between CSR activities and firm value.

5 Recently Athanasakou et al. (Citation2020) provide evidence for a U-shaped relationship between a firm’s disclosure and cost of equity capital.

6 These two views on the role of CSR disclosure among stakeholders is discussed by Cho et al. (Citation2015). The authors particularly criticize the ‘myopic view [of CSR disclosure] as a signaling device to market participants [and the negligence of] the substantial body of evidence indicating CSR disclosure’s use as a legitimating tool’ in the ‘mainstream accounting community’.