?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper studies how preparers assess users’ information needs and preferences, and how these constructions relate to preparers’ reporting decisions. Drawing on interviews as well as other internal and external data, our qualitative case study focuses on a prominent annual report restructuring at the large industrial firm Siemens. Employing the theoretical framework of institutional logics allows us to trace how Siemens’ changing context influenced the ways in which actors dynamically reconsidered the meaning and purpose of the annual report. We document how the previously coexisting compliance and stakeholder logics gave way to a dominant capital market logic, which required Siemens actors – similar to standard setters – to construct the notion of ‘usefulness’ for capital providers. Constructing users as vulnerable to disclosure overload and interested in the annual report only as a confirmatory tool, Siemens transformed the annual report into a concise compliance document. We conclude that changes in corporate reporting reflect dynamic shifts and reinterpretations of institutional logics shaped by firm-specific contextual factors.

1. Introduction

Publicly traded firms are subject to diverse reporting requirements and engage in diverse voluntary reporting practices. Whereas there is some qualitative research on specific reporting practices (e.g., Amel-Zadeh et al., Citation2019; Chahed & Goh, Citation2019; Gibbins et al., Citation1990; Johansen & Plenborg, Citation2018; Yuthas et al., Citation2002)Footnote1, we know little about the dynamically evolving within-firm context factors that influence the sense-making of actors involved in a firm's reporting process, and thus shape the resulting reporting practices.

The perceived demands of capital providers and other constituents potentially influence these practices, as they guide firms’ actors in preparing reports. We conceptualize these perceived demands as institutional logics, i.e., organizing principles that shape behavior and actions (Thornton et al., Citation2012). We mobilize this theoretical perspective to understand how micro-processes of corporate reporting change are linked to broader institutional logics. We posit that three such logics potentially influence corporate reporting decisions: (1) a capital market logic that focuses on meeting the demands of capital providers; (2) a stakeholder logic that focuses on meeting the demands of a broader set of stakeholders other than capital providers; and (3) a compliance logic that focuses on meeting the requirements imposed by regulators. Focusing on the practices of actors and their sense-making (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013), we studied two research questions: (1) How are reporting logics and their relations interpreted by key actors involved in the reporting process? (2) Which reporting strategies are developed and how are they implemented?

For this purpose, we carried out a case study of Siemens AG, a large, public conglomerate that transformed its external reporting in 2015 – most visibly by substantially shortening its annual reportFootnote2 – absent any apparent outside pressures or other stimuli. This change was publicized by Siemens and received public attention. We conducted 15 interviews reflecting the personal views and opinions of 18 individuals involved in Siemens’ annual report restructuring. To provide triangulation, we analyzed supplementary data from sources internal and external to Siemens, including Siemens’ annual reports, journal articles and conference presentations by Siemens management, as well as media articles and interviews with peer firms about Siemens’ annual report restructuring.

We found that before 2015, Siemens’ annual report combined voluminous mandatory parts along with various voluntary sections in a constantly growing ‘one-stop information hub’ that reached its peak length at close to 400 pages in 2011. Whereas the mandatory elements reflected a compliance logic that entailed providing more rather than less information to meet auditors’ and enforcers’ possible demands, the voluntary parts were an expression of a stakeholder logic, and were targeted at a broad public audience. Since Siemens adopted a reporting strategy of accumulating ever more information that amiably coexisted in its annual report, possible conflicts between these logics did not escalate.

By 2014, contextual changes at Siemens had instigated a reconsideration of the annual report's purpose, culminating in a restructuring project aimed at halving annual report length. This new objective rendered the previous coexistence of logics no longer feasible. Now shifting to a capital market logic, actors at Siemens identified capital providers as the focal users. According to their construction, these idealized users are vulnerable to disclosure overload, perceive the annual report as a confirmatory tool rather than a timely, predictive valuation tool, and are not interested in information designed for other stakeholders.Footnote3 This construction of users transformed the annual report from a sprawling ‘one-stop information hub’ for all stakeholders into a minimalistic compliance document for capital providers. This shift also reflects a reinterpretation of the compliance logic. Whereas Siemens’ prior context factors predisposed it towards over-complying with requirements, the restructuring signals a more confident view of requirements as side conditions to be met with minimal resources.

Siemens’ management actively communicated the 2015 annual report restructuring, along with its underlying rationale of enhanced user focus and capital market orientation, and perceived capital providers’ and peer firms’ reactions as largely supportive. Our analysis of public media coverage and peer firms’ perspectives revealed a more nuanced response, as we found different constructions of the focal user group of corporate reporting – not only across preparers and external parties, but also within the group of preparers. These insights imply that different preparers can follow different reporting logics – but also that even when preparers follow the same reporting logic, they might employ different assumptions in their respective constructions of users.

Our paper makes three contributions. First, we add to the limited qualitative literature on corporate reporting that has focused on the process of how companies make reporting choices (Amel-Zadeh et al., Citation2019; Gibbins et al., Citation1990) and on the construction of specific annual report elements. With regard to the latter, Chahed and Goh (Citation2019) study how the directors’ remuneration report is constructed in the UK setting by a collective of multiple actors, which renders the preparation process complex. In a comparative case study of Denmark and the UK, Johansen and Plenborg (Citation2018) reveal enablers of and barriers to change in notes disclosure in IFRS financial statements.

Complementing these studies, our analysis explores how specific within-firm context factors and dynamically shifting institutional logics shape reporting decisions. We show that contextual dynamics, such as changes in top management and corporate strategy, can bring on a new situation (Carlsson-Wall et al., Citation2016) that fundamentally changes the logics underlying the annual report – creating a ‘tipping point’ that triggers radical change. Whereas the stakeholder logic traditionally had a strong influence on Siemens’ annual report, the restructuring moved information deemed irrelevant for their ‘constructed capital providers’ from the annual report into various dispersed information channels. This emergence of a strategy of ‘separated reporting’ shows that a broad movement towards ‘integrated reporting’ (IIRC, Citation2013), which is subject to recent research (e.g., Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; de Villiers et al., Citation2014; Stubbs & Higgins, Citation2014), is not a foregone conclusion. Indeed, Siemens provides a counter-case to integrated reporting, as different information for different audiences are deliberately provided through multiple dispersed channels.

Second, our paper contributes to the limited qualitative literature on the practices of financial reporting (Hopwood, Citation2000; Robson et al., Citation2017) by looking at how a preparer constructs the user of the annual report. Young (Citation2006) explores the construction of users by financial reporting standard setters, while Stenka and Jaworska (Citation2019) reveal the importance of this abstract user category for other actors involved in the IASB's standard-setting process. Our case study shows that preparers, too, construct the abstract user and her demands when deciding what information to include in the annual report. Similar to standard-setting, these decisions are not necessarily based on systematic outreach to actual users, but rather reflect actors’ experience and subjective views of what capital providers might find useful and manageable. Obviously, these views can differ across firms.

This context is where our case links to the debate about ‘disclosure overload.’ Drake et al. (Citation2019), who provide survey evidence from users of corporate reports, and Saha et al. (Citation2019), who study the value relevance of information that might be dropped because of disclosure overload concerns, focus on users’ views. In contrast, our paper provides a preparer perspective on the phenomenon of disclosure overload by showing how assumptions about user information processing can lead preparers to focus the annual report on only the minimum of mandatory information.

Third, we contribute to literature that has mobilized the institutional logics framework to make sense of corporate reporting (e.g., Arena et al., Citation2018; Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; Edgley et al., Citation2015; Hartmann et al., Citation2018; Schneider, Citation2015). In line with this previous research we corroborate the potential of using institutional logics for better understanding the motivations and activities of preparers regarding their reporting decisions and strategies. In particular, our study highlights the dynamics of how logics influence the preparation of the annual report. We go beyond prior studies by showing how a different situation (Carlsson-Wall et al., Citation2016) might lead to reassessments of the logics underlying the annual report and their interrelation, as well as to reinterpretations (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013) of previous understandings of these logics.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Questions

2.1. Institutional Logics and Organizational Behavior

Organizations consider the preferences of diverse sets of stakeholders when deciding on their actions. Such considerations can be conceptualized as institutional logics, i.e., ‘the socially constructed, historical practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality’ (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999, p. 804). Institutional logics are not only cognitive frames of reference but are templates for individuals’ actions and constitutive of their identities (Kaufman & Covaleski, Citation2019; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). While institutional logics can constrain actions, they can also provide sources of agency and change (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008).

The original idea of institutional logics, introduced by Friedland and Alford (Citation1991), is that each institution has a central underlying logic that affects the behavior of individuals and organizations. Friedland and Alford (Citation1991) posit that different logics exist at the societal level. Thornton et al. (Citation2012) elaborate on earlier distinctions and consider the following (ideal-type) institutional orders and associated logics at the societal level: market, state, profession, corporation, religion, family and community. Studies mobilizing the institutional logics perspective typically focus on a subset of these logics as relevant in a given setting, and often further specify them accordingly. In particular, while nested in the broader societal logics, more refined and specific logics typically exist at the (lower) levels of, for example, industries, organizational fields or individual organizations (e.g. Besharov & Smith, Citation2014; Greenwood et al., Citation2011).

As ‘a multiplicity of logics are in play in any particular context’ (Greenwood et al., Citation2011, p. 332), literature adopting the institutional logics perspective has increasingly focused on how the coexistence of multiple logics affects organizations. This pertains to the relations among different logics, i.e., whether they are competing or compatible (Carlsson-Wall et al., Citation2016). Relationships between logics are subject to interpretations by actors (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013). If logics are (perceived as) competing, it depends on the organizational setup and specific constellation whether tensions arise between the logics, and how they are resolved (Carlsson-Wall et al., Citation2016).

The institutional logics perspective was originally introduced to study institutional change (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991). While such change can occur at different levels, recent literature has highlighted the potential of this perspective to study micro-processes of organizational change, and how they are linked to broader institutional logics (e.g., Currie & Spyridonidis, Citation2016; Ezzamel et al., Citation2012; Kaufman & Covaleski, Citation2019). In this vein, it can be analyzed how institutional logics are ‘actualized on the ground’ (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013, p. 167) with a focus on the practices of individual actors within organizations in light of existing institutional logics. There, logics can act as tools to influence decisions, justify activities, or advocate change (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013).

2.2. Institutional Logics and Corporate Reporting

We now consider ‘reporting logics’ – manifestations of the more general logics in the specific field of corporate reporting. Reporting logics are socially constructed approaches to making decisions about reporting strategies and practices (i.e., what information to provide, when to provide it, and how to present it). They reflect the perceived information demands and preferences of user groups that actors in companies consider relevant for their reporting. Constructing reporting logics thus comprises two steps: First, actors need to determine and prioritize the user groups they consider relevant; and, second, they need to form beliefs about the information demands and preferences of these user groups.

When deciding on their reporting strategies and practices, listed firms face demands and preferences of diverse sets of users. First, capital providers expect corporate reporting to provide information that helps them in their resource allocation and ownership decisions by informing their understanding of the reporting company's prospects and management stewardship.Footnote4 Second, other stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, employees and unions, NGOs, and the public at large expect corporate reporting to provide information that helps them with their decision-making needs, possibly informing their future activities vis-à-vis the reporting company. As the information needs of these two user groups may (partially) go unmet absent mandatory requirements, regulatorsFootnote5 expect the reporting company to comply with the rules and principles set forth in corporate reporting laws and regulations.

We posit that, consistent with these demands, preferences and requirements, three reporting logics shape the reporting of listed companies. First, there is a capital market logic, which is rooted in the market logic (Thornton et al., Citation2012). Under the capital market logic, companies provide information that capital providers demand to form their assessments of the reporting company (Hartmann et al., Citation2018) because they consider providing this information net beneficial for capital providers. Within the capital market logic, two sub-logics can be contrasted: a valuation logic and a stewardship logic (e.g., Ravenscroft & Williams, Citation2009). The valuation logic reflects the interests of capital providers in using information to develop expectations about the amount, timing and uncertainty of future cash flows. The IASB's Conceptual Framework explicitly states that IFRS follow this valuation logic (IASB, Citation2018, par. 1.2–1.3; also see Hartmann et al., Citation2018; Pelger, Citation2016; Zhang & Andrew, Citation2014). However, the IASB acknowledges that there is also a stewardship logic, which focuses on the reporting about how a company's management discharged its responsibilities, including the efficient and effective use of the company's resources (IASB, Citation2018, par 1.4; also see Pelger, Citation2020), which is particularly relevant to current shareholders. The valuation and stewardship logics, while related, can motivate demand for different information (e.g., Cascino et al., Citationin press; Gjesdal, Citation1981).Footnote6

Second, there is a stakeholder logic, which is rooted in the community logic (Thornton et al., Citation2012). Under the stakeholder logic, companies provide information desired by a broader set of (non-investor) stakeholders (Arena et al., Citation2018; Edgley et al., Citation2015) because they consider providing this information useful for these stakeholders. The stakeholder logic is often associated with the reporting of (non-financial) information about companies’ environmental, social and governance performance and sustainability (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020).Footnote7

Third, there is a compliance logic, which is rooted in the state logic (Thornton et al., Citation2012).Footnote8 Under the compliance logic, companies provide information that regulators require simply because it is mandatory to do so. In many jurisdictions, including Germany, such mandatory information comprises, for instance, the annual and semi-annual financial statements as well as a management report. As the compliance logic focuses on mandatory reporting, it also involves the expectations of the public monitors responsible for ensuring that companies adhere to these requirements (i.e., external auditors and enforcement bodies).

The ‘degree of incompatibility’ (Greenwood et al., Citation2011, p. 334) between logics is difficult to determine ex ante or from the outside. Hence, what matters for studying reporting practices and change is how individuals involved in creating reports perceive and interpret logics and their interrelations (McPherson & Sauder, Citation2013), as it is these perceptions and interpretations that influence how reporting strategies are developed and changed. Thus, our study focuses on how actors at Siemens perceive their reporting as catering to different demands and preferences, which reflects the different institutional logics at play in Siemens’ reporting organization. We do this rather than try to assess whether Siemens’ reporting does, in fact, satisfy these demands and preferences.

2.3. Research Questions

Motivated by the desire to understand the drivers of change in corporate reporting strategies and practices, this paper mobilizes the institutional logics perspective as a theoretical framework to study the reporting change that took place at Siemens, and that found its most salient expression in the sweeping restructuring of Siemens’ annual report in 2015. Specifically, we address the following research questions: (1) How were reporting logics and their relations interpreted by key individuals involved in the reporting process at Siemens? (2) Which reporting strategies were developed and how were they implemented?

3. Method and Data

3.1. Case Company: Siemens AG

Our study focuses on Siemens AG, a German firm that conducted a highly visible and unprecedented shift in its external reporting. This large, publicly traded manufacturing company initiated and implemented sweeping changes in its annual report (see section 4.2 for a detailed description) – without any obvious external pressures resulting from changes in regulation or ‘best practice.’Footnote9 The Siemens case is interesting as the company is considered a leader in the German reporting community. Siemens management frequently contributes to financial reporting standard setting.Footnote10 As one of our interviewees put it, Siemens is also known as a company that ‘other companies look up to for advice’ (CR1), not least due to the fact that Siemens’ annual reporting period ends three months earlier than that of most other companies.

Siemens itself publicized its annual report restructuring via articles and public presentations, provided us access to several members of management as well as the project team, and shared internal documents with us. These data allowed us to analyze Siemens’ internal perspectives on the project. In addition, several media responses as well as interviews we conducted with several of Siemens’ peer firms document public attention to Siemens’ project and provide triangulation for Siemens’ internal perspectives.Footnote11 We describe our data sources next.

3.2. Data Sources

Between December 2017 and December 2018, we conducted 15 interviews with 18 individuals directly or indirectly involved in Siemens’ annual report restructuring.Footnote12 provides an overview. These interviews yielded about 20 hours of audio data and 446 pages of verbatim transcripts, providing rich personal insights and perceptions into how actors at Siemens construct and make sense of the annual report and its users. Each interview lasted between 18 and 152 minutes, with a mean interview time of 62 minutes. They were conducted either by one author alone or jointly by two authors. All interviews were conducted in person, except with interviewee CR5 (by phone). One interviewee (CR1), our main contact person at Siemens, was interviewed twice, due to his deep involvement in the annual report restructuring. All interviews except one (CR8) were recorded and transcribed.Footnote13 For all interviews, we ascertained anonymity to interviewees in a signed confidentiality agreement that we had developed in collaboration with Siemens, and that was given to each interviewee before the interview.Footnote14

Table 1. Interviews with individuals involved in Siemens’ annual report restructuring

We incorporated two further sources of internal Siemens data, which deepened our understanding of the annual report's changing role at Siemens and allowed us to triangulate the interview statements. First, we reviewed articles in academic and professional journals as well as conference presentations in which Siemens management publicizes the annual report restructuring (summarized in and quoted in section 5). Second, to document the changes in Siemens’ annual reports, we analyzed the reports for the years 1998 through 2020 (see and section 4.2).

Table 2. Articles and conference presentations by Siemens personnel

In addition, we considered data reflecting external perspectives on Siemens’ annual report restructuring. First, to assess independent experts’ and media commentators’ views, we conducted a LexisNexis search of media articles containing the terms ‘Siemens’ and ‘annual report’ and published during 2013 through 2019. The search yielded 179 results. Of these, we considered five relevant, as only they contained commentary specifically on Siemens’ annual report restructuring.Footnote15 provides summaries and bibliographical detail on these five articles, as well as a key to the labels used below, and section 5.4 discusses the findings.

Second, to gauge other preparers’ responses to Siemens’ annual report restructuring, we used the opportunity of conducting interviews for an unrelated project with a non-representative sample consisting of the Chief Accounting Officers (CAOs) of six large, public German firms that would be considered Siemens’ peers in terms of public visibility and stakeholder exposure. To these interviews, we added a short set of three questions that focused on peer firm representatives’ views on, and responses to, Siemens’ annual report restructuring. Specifically, we asked peer firm CAOs whether and how they had heard of Siemens’ annual report restructuring, and what their own firm's views were – in particular, whether their firm considered itself a (potential) ‘follower’ of Siemens’ approach. summarizes these interviews conducted in early 2019, and section 5.4 discusses the findings. We refer to all data sources using shorthand labels explained in tables 1 through 5.

3.3. Interview Method

The semi-structured interview guide for our main interviews with actors involved in Siemens’ annual report restructuring was constructed to learn specifically about interviewees’ actions, experiences, and views related to the annual report. It was structured into five main question blocks regarding (1) the situation before the annual report restructuring project, (2) its initiation, (3) its organizational setup, (4) the implementation of changes, and (5) the situation after the project. While the sequence of questions varied slightly across interviews, each interview covered all core issues.

To encourage interviewees to share their personal experiences and views, while leaving them room to go as far back as they wanted, we used predominantly open ‘Why,’ ‘What,’ and ‘How’ questions (Gendron & Spira, Citation2010). Through this procedure, we were able to discover potentially relevant topics that might not have been considered beforehand, but were raised by the interviewees in their responses (Christ et al., Citation2015; Gendron & Spira, Citation2010). Another advantage of semi-structured interviews was that we were able to deviate from the interview guide at any point during an interview to follow up on and delve into specific statements by interviewees that could potentially have been informative for fully understanding the phenomenon of interest (Hirst & Koonce, Citation1996).

Two of the authors read and analyzed the interview transcripts. We examined the transcripts as to their content regarding how different institutional logics shaped the annual report. For the analysis, we did not follow a formal coding process. Rather, relevant segments of the interview transcripts were identified and recorded according to a self-developed scheme, keeping in mind different logics of corporate reporting. By moving back and forth between the interview material and theory, we strove to gain a comprehensive picture of the insights that the interviews contain with regard to the shifting role of the annual report at Siemens.

4. Case Background

4.1. Institutional Setting

As a German public firm traded on the regulated market of an EU member state, Siemens is required to prepare consolidated financial statements in accordance with IFRS as adopted by the EU.Footnote16 In addition, § 290 of the German Commercial Code (GCC) requires parent entities to publish annual group management reports (Konzernlagebericht), with content specified in § 315 GCC and German Accounting Standard (GAS) 20, Group Management Report. Other disclosures mandated for German public firms around the time of Siemens’ annual report restructuring include a list of subsidiaries, the audit opinion by the external auditor, takeover-relevant information, corporate governance, compliance and compensation reports, and a responsibility statement by the management board. As expressed in the IFRS Conceptual Framework for Financial ReportingFootnote17 as well as in GAS 20,Footnote18 these mandatory requirements are mainly targeted towards the information needs of capital providers.

Siemens’ cross-listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) from March 2001 until May 2014 necessitated additional disclosures to comply with Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requirements, in particular the filing of form 20-F for foreign issuers. The accounting literature characterizes SEC listing requirements as particularly strict, and costs of non-compliance as particularly high (e.g., Lang et al., Citation2003). Due to its U.S. listing, Siemens prepared its financial statements according to U.S. GAAP from 2001 until 2007, when it switched to IFRS, which it still follows.Footnote19 Siemens’ consolidated IFRS financial statements and group management report are subject to mandatory external audit (performed by EY since 2009) as well as to Germany's two-tier financial reporting enforcement structure (unchanged since 2005).Footnote20 Non-financial reporting only became mandatory for Siemens when Germany transformed the EU's Non-financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU) into national law (effective for fiscal years beginning in 2017).

In Germany, annual group financial statements, management reports, and other mandatory disclosures are typically provided in an annual report that can be accessed on the company's investor relations website. However, information other than financial statements and management reports are also frequently provided outside of the annual report. Furthermore, many German public firms complement their mandatory reporting by additional information, including about the company's shares, bonds and ratings, earnings press releases, presentations for investors and analysts, as well as various types of non-financial information. This information is disclosed either within the annual report or separately via the company's website.

Hence, distinguishing between German public firms’ mandatory and voluntary annual report elements is somewhat challenging in three ways: First, not all required information needs to be provided within the annual report. Second, the amount and detail of mandatory information is subject to management judgment. This discretion relates specifically to the notes to the consolidated financial statements due to the principles-based nature of IFRS (e.g., Alexander, Citation2006), but also to most management report sections. Regarding the latter, for example, Krause et al. (Citation2017, p. 241) describe the forward-looking report section within German public firms’ management reports as having ‘characteristics of both mandatory and voluntary disclosure. Despite the legal mandate to provide a forward-looking report, guidance regarding its structure, the scope of reportable items, as well as forecast horizon, precision, and assumptions is vague.’ Third, firms can also provide voluntary elements within the annual report section generally dedicated to the (mandatory) management report.

In our subsequent analysis of Siemens’ annual report content over the years, we deal with this complexity by labeling ‘mandatory’ (only) the primary financial statements and notesFootnote21 as well as the required elements of the management report and other mandatory information, whereas the residual label ‘voluntary’ applies (only) to disclosures not required to be provided within or outside of the annual report. Borrowing terms used by actors at Siemens for different parts of its annual report, we refer as ‘Book 1’ to Siemens’ voluntary information about its business, history, culture, and strategy, whereas ‘Book 2’ consists of the financial statements, the management report (with its mandatory and voluntary sections), as well as other mandatory disclosures.

4.2. Siemens’ Annual Report Restructuring

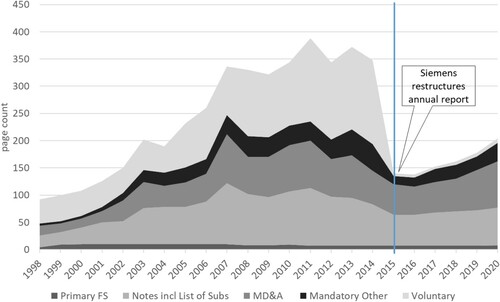

presents a summary of our in-depth analysis of how Siemens’ annual report structure evolved from 1998 to 2020. displays the page counts of the main sections layered on top of each other, and highlights the annual report restructuring in 2015 as a key event. Notably, the length of Siemens’ annual report had increased substantially since 1998, reaching a peak of 388 pages in 2011. Several insights emerge from this analysis.

Table 3. Siemens’ annual reports from 1998 to 2020

Figure 1. Development of Siemens’ annual report length over time (1998–2020).

Note: visualizes the information in Table 3, which reports the page counts of the different main sections within Siemens’ annual reports for the years 1998 through 2020. We distinguish between five elements: (1) the primary financial statements (income statement, statement of comprehensive income, balance sheet, statement of changes in shareholders’ equity, and statement of cash flows); (2) the notes to the financial statements including, when contained in the annual report, the mandatory list of subsidiaries; (3) the combined management report (excluding the voluntary sustainability and strategy sections); (4) mandatory other information; and (5) voluntary information. The vertical line demarcates the beginning of 2015, the year of Siemens’ first annual report after the annual report restructuring. Section 4.1 describes the underlying reporting requirements in more detail, and also explains Siemens’ distinction between the voluntary ‘Book 1’ of the annual report, and the largely mandatory ‘Book 2.’

In a first phase from 1998 to Siemens’ mandatory IFRS adoption in 2007,Footnote22 overall page count increased by 265%, primarily driven by the mandatory sections (+419%), but also to some extent due to the voluntary sections (+98%). This development suggests that Siemens’ annual report expansion leading up to 2007 was primarily caused by new or extended mandatory requirements. However, a different picture emerges for the period after IFRS adoption (2007) up to the annual report restructuring (2014), when Siemens’ overall annual report volume increased only slightly (by 4%). Whereas the voluntary sections, including primarily ‘Book 1,’ increased by 61% (from 87 to 140 pages), the mandatory sections actually decreased by 16% (from 249 to 208 pages).

From 2014 to 2015, Siemens’ overall annual report page count declined precipitously, from 348 to 140 pages, due to the restructuring project. The reduction mainly reflects the almost complete elimination of voluntary information, which was cut by 96%. However, the mandatory sections were significantly trimmed as well, by an average 35%, mainly by eliminating boilerplate, redundancies and immaterial disclosures (TSW2016, p. 463). Since the restructuring in 2015, page numbers have been slowly creeping again, reaching 204 pages in 2020. That increase is entirely driven by new requirements in the mandatory sections, as voluntary sections remain virtually nonexistent after 2015. The next section presents our case analysis, which explores the logics underlying these developments in Siemens’ annual report.

5. Case Analysis

5.1. Before the Annual Report Restructuring: Coexisting Logics

Our analysis suggests that, until 2014, two logics, a compliance and a stakeholder logic, coexisted to simultaneously shape the content of Siemens’ annual report.

Public statements by Siemens management, which our interviews confirmed, point to the compliance logic partly explaining the increase in annual report volume until 2014. Due to the principles-based nature of the relevant regulations (section 4.1), Siemens needed to operationalize compliance, which it did with a tendency towards providing more rather than less information (TSW2016). In addition, Siemens actors perceived ever-increasing disclosure requirements, meticulously enforced via detailed checklists, as leaving the firm no choice but to keep expanding its annual report (T2015; TSW2016; T2016; W2019).

While these developments affected all public firms, there is evidence that two Siemens-specific circumstantial factors, which were at play during the run-up to the annual reporting restructuring, reinforced the compliance logic – both in Siemens’ Corporate Reporting department and in its broader organizational culture. First, its cross-listing on the NYSE in early 2001 had made Siemens subject to the strict SEC requirements. We find evidence consistent with Siemens’ U.S. listing contributing to the perceived importance of the compliance logic in the firm's financial reporting organization, as reflected in this interviewee's statement:

Siemens followed the approach of uniform information for shareholders, regardless of their jurisdiction. Everything that is in a 20-F [document required by the SEC for foreign issuers] is, if it is of any relevance, also in the annual report. This certainly contributed greatly to the fact that the annual report was as thick as it was. (CR1)

Our compliance scandal in 2006 led us to be particularly prudent and rather put in one or two sentences more, to avoid getting into any problems by any means. (CR1)

When a customer comes to you, you usually put something in their hand and say, ‘This is Siemens’. (CC1)

The medium Annual Report was not regarded as pure financial reporting, but also as a part of our corporate communication. That's why the report consisted of two parts. ‘Book 1’, which we called ‘Company Report’, was focused on the strategic direction of the company, to put it this way. The goal was to present the corporate strategy and the core topics of the year in a way that it is understandable for a broad audience. (CC1)

‘Book 2’, the ‘Financial Report’, then concentrated on classic financial reporting as we know it from annual reports, i.e., key figures, combined management report and notes. (CC1)

While the statements in the 2013 report suggest a shift toward an integrated report,Footnote24 Siemens had been including a growing section on sustainability in the annual report since 2010 (AR2010, pp. 65–72; AR2011, pp. 66–75; AR2012, pp. 97–111).Footnote25 Comparing 2012 and 2013, both annual reports contain one subsection of the management report (with identical subtitles) devoted to sustainability, which comprises about two pages more in 2013 compared to 2012 (see AR2012, pp. 97–111 and AR2013, pp. 210–226).

The trend was always to do more. I think the trend also was to say that certain topics are now gaining in importance, and we’re starting that trend by doing more, for example on non-financial topics. You can also see this in an international context. There is a movement, and we are joining that movement and are one of the first in Germany to do something like this. (CR1)

This was the time when all these sustainability topics gained traction. This we meant to consider, and we did not want to miss the trend. There had always been a chapter on employees, always a bit on the environment, but then there was the issue, ‘Actually, we should be doing more about this. Now is the right time to do this, and it should go beyond the financials. So let's take that up.’ And then you quickly get to eight or ten topics, all of which have, at least, one page dedicated to them, as it should not look too little. (CR1)

The colleagues who did this back then also fought internal battles with Corporate Reporting for a relatively long time, arguing that sustainability issues should be included in the annual report, because this is simply part of the company's performance, which should be reported externally. At that time, people didn't talk so much about ‘Is it legally required, is it really prescribed by the various reporting frameworks?’, but you basically put things in there because you were somehow convinced of them. (Sust1)

I think we realized that the annual report had been growing so much over time by us adding more chapters or aspects – partly in order to satisfy regulatory demands, partly because the auditor asked for more information, partly because we had to include new topics like sustainability information somewhere, and some people [at Siemens] decided that the annual report would be the appropriate document to do so. And so, it gained in volume over the years. And ultimately a diverse set of objectives was combined in that one document. (Legal2)

5.2. A New Approach for the Annual Report: ‘GB-Halbe’ and Its Context

In mid-2014, Corporate Reporting launched a project to restructure Siemens’ annual report and, in that process, other channels of Siemens’ corporate reporting were also rearranged. According to our interviewees, the idea originated when the then head of Investor Relations observed that the annual reports of U.S.-listed companies (on forms 10-K and 20-F) were leaner and less ‘glossy’ than Siemens’ own report (also see TSW2016).Footnote27 In particular, these U.S. reports were perceived as lacking elements akin to those contained in ‘Book 1’ of Siemens’ annual report (CR2). The CFO and the head of Corporate Reporting quickly took up this observation and initiated a project that they labeled ‘GB-Halbe’ (CR2).Footnote28 It was then the task of a Corporate Reporting sub-department to coordinate the project, and to set up a steering committee.Footnote29 Consistent with its top-down labeling, which implied a drastic reduction in page count, the project's task now was to find ways to significantly reduce the length of the annual report.

The term ‘GB-Halbe’ was a clear signal that we did not simply want to do cosmetic changes, but wanted to make a bold move. Whether it would ultimately be 50% or 40% or 35% or 55% was not the key issue, but it was a buzzword to all those involved that it was not about reducing the font size or deleting a sentence. Rather, we wanted to structurally address this issue. We said, ‘Let us shoot for half of the size’, and therefore we called it ‘GB-Halbe’. (CR4)

Several factors within Siemens preceded, or coincided with, ‘GB-Halbe.’ First, a roster of new actors shifted the balance of power in Siemens’ top management team. Joe Kaeser, CFO since 2006, became CEO in August 2013. Under his aegis, the management board was downsized from ten to seven members. His successor as CFO, Ralf P. Thomas, has years of experience in Siemens’ Corporate Reporting department. Also in late 2013, the contract with Barbara Kux, who had been responsible for supply chains and sustainability in Siemens’ management board since 2008, expired. Simultaneously, Peter Solmssen, who had joined the board in 2007 to deal with the corruption scandal and U.S. authorities, also resigned. As Kux and Solmssen were not replaced, sustainability and compliance were added to the responsibilities of the CEO (compliance) and another existing board member (sustainability) (AR2013, pp. 92–93, 368–369). These personnel changes indicated a shift: After years of concern about compliance issues and catering to diverse stakeholders’ needs, a new focus was being sought.

Second, and consistent with a new focus on efficiency, in May 2014 Siemens announced ‘Vision 2020,’ a strategic program that, among other things, aimed at ‘simplifying and accelerating our processes while reducing complexity in our Company and strengthening our corporate governance functions,’ with cost savings of about €1b expected to be achieved by 2016 (AR2014, p. 16). ‘GB-Halbe’ was going to contribute to signaling Siemens’ general streamlining at the time.

Well, the company was supposed to become leaner, and that's what one should also see in products such as the annual report. (CR2)

These evolving contextual factors created a new and different situation that led actors at Siemens to reassess the logics involved in the creation of the annual report, and the relations among these logics. As outlined by Carlsson-Wall et al. (Citation2016, p. 56), ‘different institutional logics may be more or less compatible in different situations within an organization.’ The setting in which ‘GB-Halbe’ was conducted reflects such a ‘different situation.’ In particular, the project label implied that the former strategy of ‘piling up’ ever more information in the annual report – following the coexisting logics that had shaped it for years – could no longer be maintained. A new focus for the annual report was needed.

5.3. Reconstructing the Annual Report

Siemens found a new focus in the motto of ‘targeted capital market communication’ (the title of TSW2016). Applied to the annual report, Siemens interprets this tenet as implying that the annual report be restricted to containing elements that provide decision-useful information for capital providers (TSW2016, p. 453).

And then the decision was to use the annual report primarily as a document of pure financial reporting, serving investors with decision-useful information for profound investment decisions. (Legal2)

The objectives of the management report and the objectives of the financial statements are very well described in GAS 20 and in IAS 1, respectively. That is what we wanted to get back to: that one can understand the numbers, and everything that is not necessary for understanding the numbers of this year or next year does not belong into the annual report. (CR1)

The report was to be designed more in line with the needs of users [i.e., capital providers]. (TSW2016, p. 460)

As the relevance of information for a broad spectrum of users cannot be determined generally, firms as preparers of financial reports are responsible for selecting the relevant information within the regulatory framework. (TSW2016, p. 455)

At some point there was that kind of key event when somebody told me about discussions about including in the annual report the number of likes for our company's Facebook page. This is not a valuable basis for investment decisions anymore, but rather a development into a sole marketing instrument. […] Some things such as the Facebook likes, or how many CO2 emissions were saved, or how much waste was reduced compared to a basis year long ago – I don't know if that helps anyone with making an investment decision. Maybe I am too much financially oriented, but I focus on return on investment when I make an investment decision. (CR2)

Our view was sharpened to more critically reflect, and to once more think about, investor relevance: Is [this information item] really relevant, and which items in broader reporting may be less relevant? I believe it also changed our perspective, and that was exciting for us. Usually when we observe that there are a lot of boilerplate information in a report, where you say, ‘That does not help anyone,’ including statements about new standards that might not affect the company at all, then we have always said, ‘Please exclude this, this is confusing or misleading.’ But now, it was going further, to reconsider the general aim, reconsider: is it really relevant to investors? (Aud2)

The annual report evolved into a focused document for the financial community. (CR2)

We still created this annual report in a way as if it was a communication instrument, although that's not what it is anymore. Ultimately, we knew empirically from the last ten years, there have been no follow-up questions on the annual report. (CR5)

We see that in the follow-up questions coming from investor relations, when they forward questions from analysts or investors to us: The annual report then serves as a reference book, when they want to dig deeper, that is what we perceived. (CR2)

And investor relations were also involved and we said, ‘If there is any topic that you need or where you can anticipate that, if we take it out, the investment funds or the analysts will complain, then tell us; then that information stays in the annual report’. (CR1)

During the whole project we discussed what should be eliminated. The role of investor relations was to ask, ‘Does this make sense from a capital market perspective?’ (IR2)

We did not do any systematic surveys. We talk to the capital market every day. We generally know what is essential and what is, I would say, ‘nice to have’. And ‘nice to have,’ in our view, was not important. (IR2)

The problem is that the user is a timid animal. The user as such does not exist, and who actually really knows users’ interests? That is actually very difficult to determine, in my view, because user views are different, and users rarely articulate themselves with regard to the annual report. In this regard, we very rarely get any statements. (CR3)

Communication about performance is not provided through the annual report, not at all through the annual report. It turned away from being a communication instrument to a hygiene instrument – in the sense that it is of course super important that you document everything, that the company in a figurative sense is hygienically clean, that what you communicate through other channels has solid ground. (CR5)Footnote32

Regarding the content and the numbers, I would say for most of the capital market participants the topic is long gone when the annual report is actually published. In fact, it is a historical revision that is not really of interest for most of the capital market participants. Usually you try to anticipate the future with the information provided and, for this purpose, the annual report only has a negligible value-added. (IR1)

Our view was that we wanted to get rid of this issue of disclosure overload. That was our goal. And we said that if we could get close to that goal, we would do something good for investors because investors would no longer have to deal with this disclosure overload. (CR3)

Given that the annual report was not regarded by Siemens actors as a timely tool for valuation decisions but as a back-up set of information for knowledgeable capital providers, the disclosure overload assumption led them to limit the report to providing the information necessary for compliance purposes only.

Investor Relations said that financial analysts are actually only interested in a few key figures, and that's it. Communications said the annual report is rather inappropriate as a communication instrument, as it is only released once a year, and even though there are nice and colorful pictures included, it doesn't help us for marketing purposes, and so on. And in the end, we found we actually should write it to fulfil regulatory requirements. (Legal1)

For us as a large-cap company, it is not a communication instrument. It is a reference book. The regulator looks into that. (CR4)

Everything that is required by the regulator must stay in the annual report. We are not taking any risks, any regulatory risks, concerning an investigation by the enforcement authority. The most important guideline was: Everything that is required must still be in the document. Even if we think it makes no sense, has no significance – when the regulator says, ‘This must be in there, when it is written in the requirements, you have to report A, B, C,’ then we do it, irrespective of whether we believe that is helpful or not. Thus, from the beginning we were rather convinced that we would not get any problems with the enforcer. (CR1)

We took the table of contents of the previous annual report and in a first step our legal colleagues annotated next to each item what is mandatory, what is legally required. Then we could already tick these points. (IR1)

We as lawyers were of course strongly involved in these questions like, ‘What can we abandon, what do we want to abandon, and where do we have legal issues or grey areas? Where might we have to involve the auditor to see that we do not take any unnecessary risks?’ We primarily aimed at avoiding an unclear or even unsafe situation in which we might need to self-justify in a discussion, e.g., with the auditor. We wanted to be able to say without any reservation, ‘This is all good and right’. (Legal2)

Overall, the restructuring project ultimately manifested in notable reductions even in mandatory annual report sections (as documented in and in section 4.2), e.g., in the notes to the financial statements (change from 2014 to 2015: −25%) as well as the combined management report (−26%).

In restructuring the annual report, actors at Siemens not only considered a positive definition of what to include in its scope, but also considered complementary negative criteria to determine what to exclude, i.e., what actors at Siemens did not deem useful for capital providers. Recall that, whereas previously the ‘annual report concentrated on many different target groups’ (CC1), now greater focus was sought. The new negative definition manifested in a conscious departure from the stakeholder logic, using terms such as ‘no longer,’ or ‘refrain from’:

And then the target group was clear. We no longer wanted to address the broader public. (CC1)

I think the idea was to refocus and think about what kind of instrument the annual report is supposed to be. And the decision was to refrain from the idea of a comprehensive marketing instrument serving several stakeholders in one report. (Legal2)

We analyzed which different objectives, target groups, and content we have in [the annual report] and asked ourselves whether it would be more efficient to address them in a more target-oriented way, be it via linked separate reports on the company website, or via other means. This would probably even be a possibility to convey even more current information. (Legal2)

We said, then let us put all of this [sustainability] information into the sustainability report, so all of the sustainability information is compiled in one report and nothing is lost, but the annual report is really focused on the financial community. I believe the people who are interested in sustainability are not that much interested in the financial topics, and vice versa. (CR2)

shows that the precipitous decline in Siemens’ overall annual report page count due to the restructuring project reflects the almost complete elimination of voluntary information, with the voluntary sections being cut by 96%. This is reflected in the following interviewee statements:

Thus, some parts of the annual report were very, very quickly gone. Information about our share, I do not need that anymore, because it is on the website anyway – that is simple. Or the pictures of the management board, I do not need these, these are all on the website. These are quick wins once we agree that the annual report is no longer a communication instrument. (CR2)

In the management report, the voluntary reporting, for example about the strategy, was simply taken out. As it represents a reporting on a voluntary basis, it is in the company's sole discretion to report on such items in the management report. The company decided to remove the disclosures on the strategy, as alternative communication channels exist. Similarly, sustainability topics as well as compliance topics, while traditionally very important to Siemens, were moved to a separate communication instrument. (Aud3)

Non-financial, pre-financial or whatever you call these things nowadays. Are these important topics? Yes! But they were not important this year to understand the financials. Do we report on our employees? Of course, we have the sustainability report, we have a sustainability website, and there you find everything about how difficult it is to find new employees, the age structure of our employees, and what measures we take to manage it. Everything is there. But the difference in the age structure between two financial years was not so huge that this would have any impact on our numbers, therefore it is not part of the annual report. (CR1)

Quotes from Corporate Reporting and Sustainability illustrate that some actors at Siemens perceived a blending of the capital market and stakeholder logics within the annual report as impossible under the objective of ‘GB-Halbe.’ In particular, the perceived demands for the specificity and reliability of financial information were perceived as impossible to meet for most non-financial information (which tended to be voluntary).

I think you have, of course, differences between regulated and voluntary reporting. That is simply the breadth and depth of the topics, but also the wording. I always had discussions with the sustainability colleagues where I said, ‘This is boilerplate like nothing else: “Employees are the most important assets. Therefore, we try to find the best candidates for open positions, and we develop them further.” These first three paragraphs of your chapter on employees I can write for any DAX company. That's pointless.’ (CR1)

The great discrepancy between the two topics is: The financial side is more than 100 years old, maybe even 3000 years old if you think about it. Everything is precisely defined, well structured, built on clear guidelines, like how is something calculated, very accurate down to the last comma and precisely worded. But certain things can't be pinned down to the last comma. That's just not working. And this demand from the financial side, that the non-financial topics must be at the same level [of ‘quality’, accuracy, reliability etc.] as the financial topics, that is the reason why combining the information does not work at the moment. (Sust1)

5.4. External Responses

Prior to initiating ‘GB-Halbe,’ actors at Siemens did consider potential risks of restructuring the annual report as planned. According to TSW2016 (pp. 464–465), the project needed explaining in order to avoid it being viewed as intended to reduce transparency:

At first glance, the consistent elimination of information that is not very useful has more downside than upside potential, especially if one adopts a pioneering role and bucks the trend of constantly growing, integrated reporting. [Siemens’] innovative and disruptive approach required extensive communicative support to avoid the accusation of a reduction of transparency, given the foreseeable significantly smaller size of the annual report.

The media response tends to be more critical of Siemens’ annual report restructuring.Footnote36 Notably, three out of five relevant articles (B2016a, B2016b and B2017) report on the results of two different, widely publicized annual report contests.Footnote37 Two of these articles comment on Siemens’ low ranking among Germany's 30 largest firms in both years (B2016b: rank 26; B2017: rank 30).Footnote38 Factors highlighted in this context include Siemens having ‘dwarfed’ its annual report ‘at the expense of transparency,’ its volume reduction being viewed as ‘too radical’ and jeopardizing Germany's underdeveloped shareholder culture, with Siemens having imposed an ‘information diet on its shareholders.’ In the title of B2016a, Siemens is labeled a ‘negative pioneer,’ including due to ‘radical cuts of valuable information.’ Related to the disclosure overload debate, one jury member, a noted capital market expert, is quoted as saying: ‘Investors are perfectly capable of picking out the information they need themselves. But there must be something to pick from.’

Table 4. Media articles authored by parties external to Siemens

Table 5. Interviews with peer firms’ Chief Accounting Officers (CAOs)

Overall, our analysis of media articles shows that some external capital market experts hold views that differ from those of Siemens on the ‘disclosure overload’ debate, which makes certain assumptions about capital providers’ information processing capabilities and costs. Siemens perceives that capital providers (a) tend not to be able to find relevant pieces of information within one voluminous document, but (b) are fully capable of pulling together relevant pieces of information from multiple dispersed sources. The external commentators reviewed here tend to hold the exact opposite view. We consider these contrasting views as evidence consistent with divergent constructions of annual report users between preparers (Siemens) and external experts, even if both groups of actors generally follow a capital market logic.

Our interviews with peer firms’ Chief Accounting Officers (CAOs) also reveal different perspectives on Siemens’ annual report restructuring.Footnote39 These views range from positive to skeptical/wait-and-see to decidedly negative. Several aspects seem noteworthy. First, several respondents recall their impression, at the time, that Siemens was actively ‘marketing’ their project in what was perceived by some as an attempt to rally others behind this initiative. Second, whereas one firm (Peer 3 in ) had also reduced its annual report volume during 2014–2016 (by 7%), the CAO stressed that her/his firm's strategy and rationale had been sharply different from Siemens’. Whereas that CAO perceived Siemens’ project as focusing on one stakeholder group (investors), her/his firm had pursued a different strategy – namely to develop the annual report into an ‘integrated’ one-stop-shop for all stakeholders, reflecting a stakeholder logic. Third, the president and head of enforcement of Germany's Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel had articulated deep skepticism about ‘leaner annual reports’ (E2018), reflecting a minimum compliance logic. For example, he worried that reducing the amount of information might also impair the quality of information, and wondered how preparers could know what information users considered relevant. Our interviews reveal that Siemens’ peers consider these views held by Germany's chief enforcer relevant, with four out of six viewing them as a potentially significant deterrent for aspiring ‘imitators’ of Siemens’ approach. Finally, summarizes the six peer firms’ de-facto changes in their annual report volume around Siemens’ annual report restructuring. Even the firms whose CAOs viewed Siemens’ approach positively exhibit only very limited, if any, evidence that they ended up pursuing a similar approach. On average, the six firms reduced their annual report volumes by 1.5% during 2014–2016 – compared with Siemens’ own 60% reduction.

Overall, we conclude from this analysis that Siemens’ annual report restructuring was widely noticed by comparable firms – but that peers’ CAOs varied on whether they found it worth emulating. Further, quantitative evidence from these peers’ annual report volumes does not support the notion that Siemens’ project was widely imitated. These insights are consistent with divergent constructions of annual report users existing even within the constituent group of preparers.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

This paper documents how corporate reporting, exemplified by the annual report of Siemens, is shaped by preparers’ changing perceptions and priorities related to users’ information needs and preferences. Theoretically, we conceptualize these perceptions and priorities as institutional logics that shift over time. Two logics shaped Siemens’ annual report during the time preceding the 2015 annual report restructuring. While the compliance logic was underlying the mandatory reporting elements, in particular the financial statements, notes, and management report, the stakeholder logic was reflected in the voluntary parts, including ‘Book 1’ as well as the sustainability and strategy reporting sections in the management report. Siemens’ reporting strategy during this period was to ‘pile up’ in the annual report (1) information that was perceived as ensuring compliance with applicable regulations (with more rather than less information being provided to satisfy auditors’ and enforcers’ potential demands), as well as (2) information perceived as relevant for a broad set of stakeholders. This strategy of accumulation ensured that perceived tensions between the compliance and stakeholder logics did not escalate, thus enabling a coexistence of the two logics in Siemens’ annual report.

The setting altered fundamentally in 2014, when changes in Siemens’ management board, its delisting from the NYSE, and a company-wide efficiency program provided the context for redeliberating the role of the annual report. With the title of the restructuring project (‘GB-Halbe’) reflecting the aim of halving annual report length, the former accumulation strategy of ‘piling up’ information in an ever-growing document could no longer be maintained. The implied shortening objective imposed new conditions for annual report preparation, which led to a reconsideration of its underlying logics. A new focus of the annual report was found in the capital market logic, i.e., in the idea of providing useful information (only) for capital providers.

In operationalizing the capital market logic to determine which information to provide in the annual report, Siemens followed standard setters’ constructions of the capital provider as a knowledgeable, rational idealized user of financial information. However, actors at Siemens perceived the annual report as failing to provide timely information for this user type and viewed it instead as a confirmatory documentation tool. This was accompanied by a rationale based on concerns about ‘disclosure overload,’ entailing the view that capital providers would be served best by only minimal, necessary information in the annual report (‘the needle without the haystack’). Ultimately, following the capital market logic led the actors at Siemens to focus the annual report restructuring on compliance with reporting requirements. However, they reinterpreted the previous compliance logic, as the new focus was no longer on providing all possibly necessary information, but on providing only a minimum considered necessary to be compliant. This implied that voluntary information, reflecting a stakeholder logic, had to be moved from the annual report to separate channels, leading to a compartmentalization of information according to different logics.

Whereas a few prior survey studies on corporate disclosure highlight that analyses of companies’ internal structures are important for understanding their disclosure decisions (Amel-Zadeh et al., Citation2019; Gibbins et al., Citation1990), our in-depth case study extends this research by outlining how changes in specific context factors dynamically shape a company's reporting strategy. Changes in the company's context, such as changes in top management and corporate strategy, can bring about new situations that lead to reconsiderations of reporting strategies along the lines of different or reinterpreted reporting logics. Carlsson-Wall et al. (Citation2016) show that relations between logics are dynamic, as they might differ across situations, while McPherson and Sauder (Citation2013) highlight possible reinterpretations of the same logic over time. We show that even in the arguably narrow setting of the annual report, logics and their relations are dynamically reinterpreted and reassessed in different situations within the same company. Our interviews with peer companies, none of which followed Siemens’ approach to restructuring the annual report, suggest that firms’ contexts and logics as well as the specific assumptions underlying the constructions of users of the annual report can differ from each other. This insight encourages further field studies in this area – in particular using comparative case studies with firms adopting different reporting strategies (e.g., Johansen & Plenborg, Citation2018), in order to better understand the factors driving these decisions. The mobilization of institutional logics with a focus on the perceptions and practices underlying the preparation of the annual report seems promising for such analyses of the dynamics and diversity of reporting strategies.

In recent decades, financial reporting standard setters such as the IASB have prioritized the concerns of capital market participants, thus following a capital market logic in their standard-setting activities (e.g. Hartmann et al., Citation2018; Pelger, Citation2016; Ravenscroft & Williams, Citation2009; Young, Citation2006). As outlined by Young (Citation2006), standard setters developed the ideal-type knowledgeable rational capital provider as the point of reference to continuously construct, in interaction with their constituents (Stenka & Jaworska, Citation2019), what they perceive to be in line with the preferences of this ideal-type user. Despite several recent studies providing relevant insights (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2015 for sell-side analysts, and Cascino et al., Citation2014, in press for users more generally), users’ information needs and preferences are still not very well understood in accounting research. However, Georgiou (Citation2018) reveals, for the example of fair value accounting, that the ideas of the IASB as to what information capital providers would like to see in the financial statements do not necessarily resonate with, and might rather be opposed to, the actual preferences of these users. Interestingly, Georgiou (Citation2018) outlines that this situation does not lead to resistance by capital providers or any attempts to lobby the IASB, but rather to a state of ongoing ‘dissonance.’Footnote40

When applying principles-based regulation following a capital market logic, such as IFRS, preparers also face the difficulty of determining what they perceive as useful information for capital providers. Very little is currently known about how such assessments are made. Our study shows that Siemens adopted two different approaches: First, in a rather passive approach, Siemens followed actual and anticipated demands by auditors and enforcers, which led to the compliance logic driving the mandatory parts of Siemens’ annual report before 2015. In this case, auditors and enforcers are in a crucial position to promote the interests of capital providers. Second, adopting a more self-confident approach, Siemens actors constructed capital providers’ needs as fulfilled by the minimum of information necessary to meet regulatory requirements, reflecting a reinterpreted form of the compliance logic. Siemens actors’ construction was based on the two assumptions that the annual report largely serves documentation and confirmatory purposes, and that users need to be protected from disclosure overload. Notably, Siemens refrained from collecting systematic evidence on capital providers’ actual needs,Footnote41 but concluded from regular interactions with professional users and a lack of questions about certain information items that these items are not accessed by users, and hence are irrelevant to them.

The first assumption was that the annual report is a documentation tool, a ‘hygiene’ instrument instead of a timely predictive tool for capital providers. Along this line, the annual report has an important accountability/stewardship role in practice, a role of financial reporting that has only very recently been (re)acknowledged by the IASB (Pelger, Citation2020). However, the annual report can also provide valuation useful information: Ball and Brown (Citation1968, p. 176) concluded more than 50 years ago that ‘the annual income report does not rate highly as a timely medium, since most of its content (about 85–90 per cent) is captured by more prompt media which perhaps include interim reports.’ In the IASB's Conceptual Framework, timeliness is included as an enhancing qualitative characteristic (IASB, Citation2018, para. 2.33), i.e., a desirable but not fundamental characteristic of useful financial information. Instead, relevance is regarded as a fundamental characteristic. It is defined as ‘information [that] is capable of making a difference in the decisions made by users’ (IASB, Citation2018, para. 2.6), i.e., ‘it has predictive value, confirmatory value or both’ (IASB, Citation2018, para. 2.7). From this perspective, it is primarily the confirmatory value that makes the annual report decision useful ‘if it provides feedback about (confirms or changes) previous evaluations’ (IASB, Citation2018, para. 2.9). The annual report is relevant for capital providers’ valuation decisions as their expectations that voluntary and interim information would subsequently be included in the annual report renders this information more reliable and trustworthy ex ante.Footnote42

The second key assumption underlying Siemens’ approach relates to disclosure overload. Concerns about disclosure overload have been raised primarily by preparers (Drake et al., Citation2019). However, surveys of users point in a different direction. For instance, the CFA Institute (CFA Institute, Citation2013) complains about the absence of investors’ views in the debate on disclosure overload and reports survey findings from investors which, among other things, show that ‘76% of respondents do not currently observe the inclusion of obviously immaterial information in financial statements’ (CFA Institute, Citation2013, p. 75).Footnote43 Drake et al. (Citation2019) find that the professional users they surveyed do not see a problem of disclosure overload, but rather state that the amount of information provided is just right or even too little. In a similar vein, Saha et al. (Citation2019) document that items suggested by professional guidelines to be eliminated from corporate disclosures due to disclosure overload concerns are value-relevant for some firms. These studies are consistent with the reactions to Siemens’ annual report restructuring that we document in some media articles, and that highlight the abilities of capital providers to ‘pick’ relevant information from a report, as well as their preference for information to be provided in one place, rather than being dispersed across multiple channels. Interestingly, in direct interactions with its capital providers, Siemens reports not receiving negative, if at all any, feedback on the revised annual report. This might indicate (implicit) support or indifference by the users as well as a state of ‘dissonance.’

Finally, the Siemens case sheds light on the debate about integrated reporting. The absence of the stakeholder logic in its revised annual report, and its compartmentalization of information for different stakeholder groups through dispersed channels, make Siemens a counter-case to movements towards ‘integrated reporting’ recently highlighted in the literature (e.g., Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; de Villiers et al., Citation2014; Stubbs & Higgins, Citation2014). This simultaneous disclosure of financial information intertwined with non-financial information in one report is thought to support long-term value creation along with efficient and sustainable provision of financial capital (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; IIRC, Citation2013), leading companies to adopt ‘integrated thinking,’ which will result ‘in efficient and productive capital allocation, […] [and] act as a force for financial stability and sustainability’ (IIRC, Citation2013, p. 2). Our case shows that the development towards integrated reporting is subject to certain firm-level conditions, and thus may not be widely achieved – unless made mandatory. The deeper notion of ‘integrated thinking’ (and, one might add, acting) may depend even more strongly on such conditions.

Siemens appears to have moved in the opposite direction by focusing the annual report on material, mandatory capital-market-oriented information, while providing additional information for capital providers as well as information for other stakeholders through other channels. The situation at Siemens right after the annual report restructuring, which featured separate reports (e.g., on sustainability) and web-based information (e.g., on corporate strategy), could be labeled ‘separated reporting,’ as it supplies different user groups through different channels. Along this line, it should be noted that, whereas Siemens substantially shortened its annual report, it did not reduce the overall quantity nor quality of information provided to stakeholders. Siemens now provides information through multiple channels, including on the corporate website, instead of in a ‘one-stop’ annual report. This raises the interesting empirical question whether providing information via one central document versus multiple dispersed communication channels affects how different user groups perceive a firm's information environment, e.g., in terms of information processing costs.

It will be interesting to see whether compartmentalization is a ‘sustainable’ reporting strategy in the longer term. The European Commission has emphasized its interest in non-financial reporting, and further mandatory reporting in this area is under development.Footnote44 While Siemens tends to oppose such additional reporting requirements (W2019), these developments might still lead it to reconsider its reporting strategy in the future, as compartmentalization is arguably more difficult to uphold in a situation where regulators – and possibly also capital markets – demand non-financial information of increasing quantity and quality. Thus, the stakeholder logic could still experience a revival in Siemens’ annual report in the future – due to the requirements of regulators. However, Siemens’ annual reports up until 2020 show no such revival.Footnote45

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Beatriz García Osma (Editor), three anonymous reviewers and Catalin Albu, Nadia Albu, Stefano Cascino (discussant), David Cooper, Thomas Fischer, Omiros Georgiou, Martin Messner, Maximilian A. Müller, Alexander Paulus, and Rafael M. Zacherl, participants of the workshop ‘Financial Reporting and Auditing as Social and Organizational Practice 4’ at the London School of Economics, the 35th EAA Doctoral Colloquium in Larnaca, the 42nd EAA Annual Congress in Paphos, the 6th Workshop on the Politics of Accounting at the University of Manchester, the 1st EAR Annual Conference, the 2020 Annual Conference of the TRR 266 Accounting for Transparency, and research seminar participants at LMU Munich, University of Innsbruck, University of Mannheim, and University of Bucharest for valuable comments on prior versions of this paper. Most notably, we gratefully acknowledge the support of interview partners from our case company Siemens AG and its audit firm.

7. Disclosure statement

Subsequent to the initial submission of this paper to the European Accounting Review one of the authors entered employment at one of Siemens’ subsidiaries.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These specific disclosures include, for example, the remuneration report (Chahed & Goh, Citation2019) or the President's Letter and MD&A (Yuthas et al., Citation2002).

2 Whereas corporate reporting is multi-layered, the annual report of public firms is often regarded as a key communication instrument (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2014; Yuthas et al., Citation2002). Its main purpose being to provide information to internal and external parties (Firth, Citation1980), it is sometimes viewed as the primary source of information for them (Ertugrul et al., Citation2017).