Abstract

It is acknowledged that identity regulation in organizations relies on discursive resources. This study moves beyond discourse – illustrating how discourse and accounting measurements are mobilized together in revising identity. Measurement produces persistence, clarity, transparency and comparability, as well as direction: Accounting’s quantitative knowledge ‘amplifies’ discourse. We explain the Great Alliance between words and numbers in a case study addressing events in an organization’s transformation. This extends our understanding of what takes place on the interface between identity and accounting.

1. Introduction

Regulating the identity of those who work for you is a powerful way of managing. The reorientation of the worker’s self-image gives management a grip on enduring questions: Who am I? And what will I become? By regulating identity, managerial aspirations are disseminated and objectives translated into action. Identity regulation is a way of securing organizational control (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002). Words are a key resource in this endeavor. Words of emotive or moral appeal seep into texts, narratives, and argumentation – and into the consciousness where identity is embedded: Discourse has been recognized as a central medium in regulating worker identity (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002; Bardon et al., Citation2017; Watson, Citation2008; Clarke et al., Citation2009; Brown & Humphreys, Citation2006).

Identity and its regulation have been addressed in numerous accounting studies, focusing often on management accountants’ changing expert identities (e.g., Lambert & Pezet, Citation2011; Morales & Lambert, Citation2013; see Wolf et al., Citation2020 for a review). Some identity-related accounting studies have addressed the broader interface between accounting and organizational identity (Abrahamsson et al., Citation2011; Empson, Citation2004; Järvenpää & Länsiluoto, Citation2016). For the positioning of this study, a number of accounting investigations which recognize the role of discourse in transforming the subjectivity of accountants become essential (Covaleski et al., Citation1998; Gendron, Citation2008; Gendron & Spira, Citation2010; Goretzki & Messner, Citation2019; Järvinen, Citation2009; Morales, Citation2019). Our study is informed by these discourse-related investigations. It moves, however, beyond accountants – and beyond discourse per se in identity regulation. This study investigates how accounting measures, in conjunction with discursive elements, become mobilized for regulating the worker’s identity, at the workplace. It focuses on the constitutive role of accounting artifacts – not on investigating the identities of accounting professionals.

The study thus looks at accounting in action. It connects identity regulation with accounting phenomena in a different way, approaching from another vantage point: It investigates how discourse and key elements of accounting, financial as well as non-financial measurements, are deployed in an interlaced attempt to revise worker identity. The partnership between words and numbers, the Great Alliance between verbal elements and the constitutive power of accounting (Burchell et al., Citation1980; Hopwood, Citation1986, Citation1983) aims at the regulation of identity by focusing on work itself. Together, words and measurements redefine what work is to become. And what work is to become offers the prospect of regulating what the worker is to become: You become what you will do.

Identity, or the constitution of the ‘self,’ has attracted a perplexing volume of scholarly curiosity. It has been used in different disciplines, ranging from social psychology to philosophy (see e.g., Collinson, Citation2003, pp. 528–529). It has contributed to numerous theoretical discussions and empirical efforts, invigorating a plethora of debates (Schultz et al., Citation2012; Taylor, Citation1989). Identity has also been understood in different ways (see e.g., Brown, Citation2015; Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003, pp. 1166–1169.) Hence, an anchor point is needed. With its accounting-related considerations, this study seeks to refine the framework of identity regulation put forth by Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) – building thus on the following: ‘For interpretively inclined organizational researchers, identity holds a vital key to understanding the complex, unfolding and dynamic relationships between self, work and organization’ [italics added], (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, pp. 8–9).

Traditionally, accounting has been the carrier of the capitalist ethos and ‘business logic’ in organizations (e.g., Dent, Citation1991). It provides the basis for financially sound management and governance of the enterprise through measurements of e.g., sales, costs and profitability (Miller & O’Leary, Citation1994, Citation1987). These calculative practices are mobilized for controlling the local realities where selves are nested. However, more recently accounting has added deep-probing non-financial measurement into its repertoire, for instance within the framework of The Balanced Scorecard – and in initiatives of monitoring, benchmarking and ‘auditing’ key operational processes (e.g., Bogetoft, Citation2012; Chambers & Rand, Citation2010; Franceschini et al., Citation2007; Kaplan & Norton, Citation1992, Citation1996, Citation2007; Liebfried & McNair, Citation1992). These micro-measurements cast light on organizational affairs beyond traditional financial visibility: They expose the detail of operational processes (Vaivio, Citation2006, Citation1999). They suggest the ‘quantification’ of work beyond its outcome – by focusing on the how of work. Accounting can more effectively contribute towards the regulation of identities within the operational workflow. In this study, both financial and non-financial, operational measurement – alongside discursive elements – served as potent vehicles in mediating managerial aspirations in identity regulation. Organizations, as Collinson (Citation2003, p. 541) points out, do not only produce products and services but also people.

The study contributes to accounting literature by suggesting that accounting is powerful quantitative knowledge in the regulation of worker identity. As will be explained in the study’s conclusions, this power stems from the production of (1) persistence, (2) clarity, (3) transparency and comparability as well as from the production of (4) direction. The study illustrates how these properties of accounting artifacts, as quantitative materializations of discourse, become essential within identity regulation. Explicating the functioning of the Great Alliance between words and numbers extends our understanding of how accounting assists the emergence and control of the appropriate worker in organizations. But it also raises questions regarding management accountants’ identity and the de facto functioning of calculative practices within control ‘packages’ (Malmi & Brown, Citation2008).

Next, the paper first lays out its underpinnings in discourse-related accounting studies on identity. It moves on to discuss what we understand here with identity and its regulation. Chapter four describes the study’s method and fieldwork at the Finnish Motor Vehicle Inspection Ltd. (FMVI). The paper’s next chapters depict events at FMVI, around ‘The Inspector’ – the worker of this study. The final chapter sets our conclusions against the theoretical starting point and discusses their implications in the accounting domain.

2. Identity and Discourse in Accounting Research

First, a classic investigation of how identity representations were shaped in Big Six accounting firms needs to be acknowledged: Covaleski et al. (Citation1998) examined how accounting professionals became more disciplined organizational members through the language of management programs, like Management by Objectives and ‘mentoring.’ Discursive elements and calculative techniques, like sales targets and client billings, played central roles in this Foucauldian process of normalization (Foucault, Citation1979).

Identity threatening events and the reflective ‘identity work’ of professional accountants, in a failing Big Four – organization that circulated discourses of ‘commercialism’ and ‘risk,’ are at the focus of Gendron and Spira (Citation2010). Discourse, its experience and its translation – as well as individual reflectivity – are here the key components of identity work that seeks to revise (or maintain) identity: ‘The individual’s subjectivity therefore constitutes one of the key arenas in which discourse construction and discursive contests take place’ (Gendron & Spira, Citation2010, p. 277). Four interpretive schemes characterized identity work and the production and reproduction of discourse – within the discursive turbulence of the study’s context: disillusion, resentfulness, rationalization and hopefulness. For this paper’s theoretical aspirations, how disillusion involved a sense of powerlessness and incapacity within subjectivity, and how a degree of optimism characterized hopefulness in identity work, stand as important reference points.

Identity representations of academics as ‘performers’ – subject to the discourse of ‘performativity’ (Lyotard, Citation1979) and the normalizing technology of performance measurements, like journal rankings – has also been addressed (Gendron, Citation2008): Performance measurement as a discursive technology has colonized the academia, regulating identity. It underpins superficial judgments about the self. Academics compare themselves with ‘significant others’ with measurement schemes. ‘Academic accounting’ may lead to conformity and stifle innovation (see Englund & Gerdin, Citation2019; Gendron, Citation2015), resonating with our argument on how accounting’s inherent power of transparency and comparability assist in transforming representations of the self.

We acknowledge how management accountants’ identity narratives in positioning themselves as ‘business partners’ build on the concept of the storyable item (Goretzki & Messner, Citation2019). This contains a discursive element, alongside symbolic and dramaturgical ones, but underlines discursive confusion (Down & Reveley, Citation2009). Ideational storyable items, mobilized as discursive resources in backstage and frontstage interactions relating to identity work, help the creation of a shared narrative. They render aspirational identity meaningful. In a self-reinforcing manner they regulate management accountants’ identity (Goretzki & Messner, Citation2019, pp. 16–17). Other accounting studies granting a role to discourse include Morales’ (Citation2019). Examining symbolic categories in shaping identity, he states: The struggle for recognition ‘ … is played out at a symbolic and discursive level as well as at a material one’ (Morales, Citation2019, p. 275). Moreover, the purpose of an investigation on a shift in the New Public Management agenda was ‘ … to study how a change in the NPM agenda and discourses influenced the occupational identity and roles of management accountants’ (Järvinen, Citation2009, p. 1203).

3. Perspectives on Identity and Its Regulation

What then, does identity mean here – as we are tracing identity’s unexplored connections vis-à-vis the accounting domain? For this study, identity suggests a self-image, a temporarily stabilized subjectivity that shop floor workers construct from available elements – including discursive resources – within an organizational context (Brown & Humphreys, Citation2006; Clarke et al., Citation2009). Identity gives an understanding of who you are, why you are significant and what do you desire to become. Identity is a legitimate narrative, a self-presentation (Ashforth & Schinoff, Citation2016). It maintains meaning and self-respect in the local space of a working collective. For this investigation, identity also stands as a storyline of why often boring workplace life still makes sense, and why ‘hands on’ expertise and the narrow possibilities for self-actualization still are contributing to perhaps more elevated goals. It is an account, to yourself and ‘significant others’ (Collinson, Citation2003, p. 538), about the roots of your integrity and your modest status-claims.

Identity is not firmly stabilized. It appears as a fluid, precarious construction. Representations of the self are dynamic; identity is a ‘project.’ It involves tensions, struggles and fragmentation (Watson, Citation2008, p. 124). Competing discourses may influence ‘identity work’ – the revision of identity (Brown, Citation2019, Citation2015; Clarke et al., Citation2009). Identity work is a gradual, ongoing process. But it can be conceived as something abrupt – being triggered by radical transitions or a dominating discursive regime. Our understanding of the mechanisms of identity work remains somewhat poor, (Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003, p. 1164). This study underlines what sets into motion, informs and guides revisions in worker identity: It focuses on a context that prompts ‘feelings of confusion, contradiction and self-doubt, which in turn tend to lead to examination of the self’ (Brown, Citation2015, p. 25). Moreover, this study looks at identity work as a target of regulation.

During organizational change, discourse is a key resource in identity work (Kenny et al., Citation2011; Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003). The identities that people constitute and reconstitute draw on discursive regimes (e.g., Bardon et al., Citation2017; Kornberger & Brown, Citation2007). Discourse is a powerful way to regulate identity. It offers existential positions and legitimate meaning in everyday action. These give the ordinary worker moral ‘high-ground’ as well as secure ontological and epistemological spaces to occupy (Clarke et al., Citation2009, p. 325). Discourse provides ways to narrate the self in a socially validated way. The appealing rhetoric of a discourse is a vehicle for re-examining and re-authoring the self. For the ordinary worker, on the ordinary working day, discourse contains idealizations that turn work into something more fundamental. Discourse recasts the ordinary as something extraordinary. In this study, the discourse of ‘The Customer’ became central for understanding how shop-floor workers reshaped their subjectivity.

However, we should not conceive relationships between discourse, identity work and identity regulation as unproblematic. In multi-discursive settings, organizational agents face disorienting discourses (Clarke et al., Citation2009; see also Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 637; Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003, pp. 1183–1184). And discourse can remain distanced from operational realities. It does not automatically induce organizational agents into revisiting subjectivity. It can remain insensitive to micro-contexts, reducing into an abstract notion of the management élite, difficult to internalize and deploy. Therefore, e.g., many strategy-related discourses produce tensions or fade away (Hardy & Thomas, Citation2014; Mantere & Vaara, Citation2008). Discourses may be received as hegemonic threats. They trigger resistance instead of ‘positive’ identity-work (Collinson, Citation2003). Moreover, a discourse can appear as incoherent: It requires too radical revisions of the self or implies conflicting loyalties; anxiety and fragmentation of workplace selves may follow. The verbal content of discourse often remains ambiguous: Mere words are understood in nebulous ways – confusing the self. But as our study illustrates, an ambiguous discourse becomes reinforced with the persistence and clarity of accounting’s systematic representations, both financial and operational. Accounting is a technology that accords visibility to events, and ‘translates qualities into quantities’ (Miller, Citation1994, pp. 2–3). Hence, this alliance offers an effective way to regulate selves at work.

Identity regulation is a less obtrusive mode of organizational control. It seeks to influence the ‘inside’ of employees (Deetz, Citation1995) – by informing the self-definitions, the workplace feelings and the operational priorities that constitute self-narratives. It directs identity-work into predefined alleys. These are congruent with the organization’s objectives, as defined by management and conveyed by discursive regimes (see also e.g., Bardon et al., Citation2017 on how discourses on ‘effectiveness’ and ‘ethics’ influenced middle managers’ identity work). In their seminal study on identity regulation, Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) bring discourse to the nexus of the argument: Organizational control materializes in the self-positioning of employees within managerially generated discourses. Discourse is a central pillar in their reasoning. Discourse per se plays a critical role ‘in processes of identity formation, maintenance and transformation’ (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 627).

Identity regulation, explained by Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002, pp. 625, 638), is located within the context of discourses essential for identity work, and ‘encompasses the more or less intentional effects of social practices upon processes of identity construction and reconstruction.’ But identity regulation may also be pursued less purposefully. It can be ‘a by-product of other activities and arrangements typically not seen – by regulators or the targets of their efforts – as directed at self-definition.’ Identity regulation takes place in mundane contexts; it is not dominant of managers’ minds. And management is not omnipotent in regulating subjectivity (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, pp. 621, 635). Employees interpret discourse critically. Workers may experience identity tensions (Gotsi et al., Citation2010). Resistant selves appear when employees contest orchestrated self-images (see Bardon et al., Citation2017, p. 942; Collinson, Citation2003, pp. 539–541).

Facilitating an analysis of identity regulation, Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) suggest nine modes of regulation.Footnote1 These offer ‘a broad view on how organizational control may operate through the management of identity primarily by means of discourse’ (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 629). This study has been informed by this method theory (Lukka & Vinnari, Citation2014) – seeking to refine it with unexplored accounting considerations. Three dimensions in identity regulation – resonating with our empirical evidence – focus our study: (1) The interpretive framework addresses first the definition of the context: By explicating the scene or the Zeitgeist where the organization operates, a particular actor identity is implicitly invoked. (2) We then trace the establishment of distinct ‘rules of the game’ within this broad context: The naturalization of rules and standards for doing things at work, calling for a reshaped self-understanding. (3) Finally, our main focus is on knowledge and skills: Since knowledge often defines the knower, what one is capable of doing (or expected to do) in organizational action frames who one ‘is.’ For instance educational programs – as well as a mobilization of the accounting measurements examined in this study – articulate new competences and call for revised action.

Hence, summarizing these dimensions, this study addresses the context (1 and 2) as well the action orientation (3) of the worker whilst investigating the interlacing of discursive elements with accounting-related calculative resources, in regulating identity (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 632). This study seeks to refine the framework of Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) by suggesting that knowledge in identity regulation is not exclusively discursive but accounting-related and quantitative: Financial and operational performance measures are vehicles for regulating the self.

4. Method and Fieldwork

We follow the interpretive mode of theorizing, applying the case study method (Ahrens & Dent, Citation1998; Lukka & Modell, Citation2010; Scapens, Citation1990; Vaivio, Citation2008). Identity, in processes of identity regulation, is a fluid and slippery phenomenon. It is intertwined with organizational change, discourses and multiple practices at the workplace. Identity cannot be observed directly. It is a theoretically grounded conceptualization, leading some identity scholars to ask: ‘How might we study a phenomenon that is not conceived as a thing?’ (Gioia & Patvardhan, Citation2012, p. 55). Operationalizing identity in empirical inquiry is challenging (Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003, p. 1170). Even educated senior managers can be hesitant on how ‘identity’ is to be understood. And they can be wary of admitting any ‘regulation’ of worker identity. At the grass-root level, questions on ‘identity’ lead to confusion, loss of bondage with interviewees – or to contaminated answers, when shop-floor workers misunderstand it. Empirically, identity should be studied indirectly.

Studying identity and its regulation indirectly calls for a method that reaches beyond surface observation – and gauges events over time: The nuances of self-images surface when set against a historical backdrop. The study emphasized the collection of multifaceted, valid and reliable interview data (McKinnon, Citation1988). It aims at a polyphonic account – a historically anchored narrative where interviewees were allowed to speak generally about their organization, how they experienced work, how their tasks and working conditions had changed, what concerns they had regarding particular initiatives or practices etc., following earlier, established identity studies (e.g., Brown & Humphreys, Citation2006, pp. 235–236; Clarke et al., Citation2009, p. 330; Gagnon & Collinson, Citation2014, pp. 650–653; Kornberger & Brown, Citation2007, pp. 501–503). Investigating identity indirectly, the interview themes / questions did not include expressions related to ‘identity’ (see Gotsi et al., Citation2010, pp. 786–787). Identity regulation is an organizationally embedded phenomenon. It becomes explained as a plausible interpretation of events. For this, a solid understanding of the empirical context, its antecedents and its dynamics is critical.

In the interviews and within the multiple rounds of iterative interpretations of data, we emphasized theoretical sensitivity. Identity regulation is an a priori framework guiding data collection and its interpretation. In this investigation of empirical events, spanning over several decades, the study was guided by earlier theorizing, most notably by Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) – and the pre-understanding it provided. However, these frameworks were not predominating to the extent of making us ‘blind’ to fresh empirical insights (see Ahrens & Dent, Citation1998; Dyer & Wilkins, Citation1991) and analytical induction (Gioia & Patvardhan, Citation2012). Hence, the study provides a historically informed account (Ahrens & Dent, Citation1998; Kakkuri-Knuuttila et al., Citation2008), contributing to theory refinement in identity regulation and accounting literatures (Keating, Citation1995; Lukka & Vinnari, Citation2014).

The paper’s empirical part focuses on organizational change and identity regulation, in a former public authority. It depicts how this case organization, previously owned by the state, became transformed into a business organization, operating as the Finnish Motor Vehicle Inspection Ltd. (FMVI). The study first backtracks to 1968 when cars inspections became organized. It then follows events extending until the early years of this millennium, reshaping what car inspection stands for today. Interviews are the study’s primary source of data. These took place mainly in 2002–2003, with several follow-up interviews in 2008, 2013 and 2019 – on all organizational levels, and in multiple locales. 30 interviews were conducted; totaling about 36 interview hours (see Appendix 1). Not only higher-level managers were interviewed. The study addressed mostly workers – car inspectors and other operational personnel – in the setting of daily life at the workplace. The study also relied on informants no longer active at FMVI. Furthermore, we moved beyond the organization’s boundaries, speaking to customers with experiences extending far back. These discussions are not, however, part of the tape-recorded data, but were memorized by field notes: Car owners have plenty to tell about vehicle inspection’s dramatic change. The field interviews were not uncritical recordings. ‘Probing’ questions were asked. Interesting cues were followed in more depth, checking their robustness (McKinnon, Citation1988) – but without leading the interviewees into preconceived alleys.

The field interviews were complemented, in the spirit of data triangulation (McKinnon, Citation1988), by other sources of evidence – management documents, an internal audit handbook, evaluation sheets, memos, control reports, articles in business press, as well as advertising material. A published history of car inspection in Finland (Sornikivi, Citation1996) provided an invaluable documentary source: We were able to reflect on our understanding of events and check on the accuracy of critical facts. Finally, on-site observations on numerous inspection stations, regarding the condition of their now relatively standardized premises, their workflow, and the routines of customer-service, provided a deeper understanding about the study’s empirical context.

5. The ‘Old World’ of Car Inspection: A State Bureaucracy

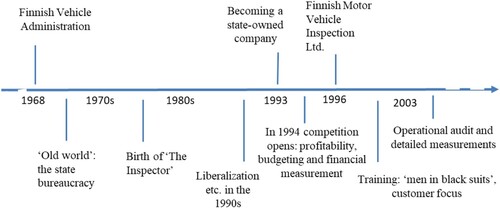

For understanding the worker’s identity and attempts to regulate it, this study’s fieldwork gauges events of the late 90’s. In what follows, we mount the concept of ‘The Inspector’ – casting light into the changing subjectivity of The Inspector, the worker of our narrative. The description first goes back to what we call the ‘Old World.’ Its dawn was in the 60’s, when car inspections started to run on a large scale. Here, we uncovered the building-blocks of an ‘Old World’ identity (see Figure . for a timeline of key events).

5.1. In a ‘Militaristic’ Hierarchy – but as a Team

A law requiring regular car inspections was passed in 1922. These were carried out by certified car inspectors. In 1968, car inspectors were organized under a new government body, the Finnish Vehicle Administration (FVA). In 1971, the government proposed to build a total of 46 car inspection stations, whose employees operated as civil servants. Car inspection, described as a ‘state bureaucracy,’ followed an almost militaristic order. On the top was the Managing Director of FVA. On the next level, a regional logic had instituted Province Inspectors. Their authority extended to stations within a province. At the station, a sense of public duty prevailed. The Head of Station was responsible for its activities, equipment and administration. But everybody worked on incoming vehicles: Daily work took place in a small team. These technical professionals of motoring safety were ‘hands on’ with the mundane practices of car inspection. Most inspectors had a technical background. ‘We only talked about cars,’ an interviewee (K.H.) recalled. The mastery of ‘nuts and bolts’ was a key pillar of self-respect.

For workplace identity this also suggested a sense of security and predictability. An operational knowledge base was shared. A narrow technical vocabulary was used – ranging from worn brake-pads to overly rusted undercarriage. These elements were embedded in an egalitarian collective – where an esprit de corps had formed around technical and physical challenges. Loyalty was important for a coherent self-image:

On many stations, the spirit was really good. Like ‘we do this job’. And it was done in a team already in those times … They helped each other. If somebody was squeezed a bit, another guy would go and help. (K.S.)

5.2. The Inspection: Cars and Subordinates

For understanding The Inspector’s stabilized subjectivity it is essential to underline the legal elements that framed work – differentiating the self vis-à-vis others: The Inspector was a state official. A legally inscribed distance was present in the interactions between The Inspector and car owners. A sense of power and superiority prevailed:

We were public officials. You could see it everywhere. We were officials – and then you had subjects under us. (H.J.)

We were actually public officials … A badge or card, what was it … That gave us the rights and duties of a policeman in those days. So, it’s both ways: It’s good and it’s bad. But that responsibility then binds behavioral patterns, molds them a bit – and actually it does it around the clock.

In the 1970s a man arrived with a Soviet-made Lada, a popular car in those days. For the checking of wheel-suspensions, he was supposed to turn the steering wheel at The Inspector’s orders. As he failed to react instantly, The Inspector looked up and yelled: ‘Turn the wheels, you bloody communist!’ (K.S.)

5.3. A Centralized Budget Economy

In terms of accounting, everyday reality was predictable. All stations belonged to a centralized system. FVA received a budget from the state, allocating it further. Station heads had little autonomy. Each station was a cost center. Accounting was in a marginal role. ‘Numbers’ were not coupled to subjectivity in a significant way. They were constraining self-actualization. But accounting was not essential for the construction of The Inspector’s identity-narrative. It did not prompt any identity work. This does not suggest that an awareness of costs and expenses would have been unimportant.

It [the budget economy] meant, in practice, that a budget was prepared for certain things annually … A certain amount is then at your disposal and it runs to an end at some point, and no more is coming. And then, in the end of the year, if something is left there, you use everything. Then next year you would get at least that amount. (H.J.)

For example pencils could become a rarity … And often inspectors also use ball-point pens for inserting their notes into inspection documents, and it went so far that actually you had to beg for a new ball-point pen if the ink had run out. And you had to show that it really had run out! That at some point of the year we were really so hardly squeezed … (H.J.)

5.4. Operational Diversity: Different Premises, Different Personalities

Trying to understand The Inspector’s subjectivity, the decoupled settings should be acknowledged. Each station had its local characteristics. Diversity prevailed. And the stations remained relatively isolated from each other, as one interviewee explained:

We didn’t have computers and alike, wherefrom information is disseminated. And only the big bosses travelled and went between stations. This meant that the ordinary guy did not know very much about other stations. (M.S.)

Different workloads and technical capabilities were conditioning the creation of the self. The heterogeneous, non-transparent character of the ‘Old World’ suggested varying quality in car inspection. The Inspector’s action depended on the local context and the particularities of the self. Differences in attitudes also mattered. Identity at work and personal characteristics are inextricably intertwined.

It depended very much on the head of station’s personality. Who was putting in the effort and in what kinds of things … It was a kind of bureaucratic activity. There was no need to think about it in terms of the customer. You went ahead a bit according to your own whim and mood … What was the head of station’s or the inspector’s mood at that moment? And what happened to be the time of the day, or the weather? Of course it was done outside. And if it started raining … So I mean how you were treated as a customer on that moment – it was different to what happened on a sunny day. (J.S.)

6. The Transformation of the 1990s

6.1. The Emergence of a New Zeitgeist

In the beginning of the 90’s something unexpected happened: GDP contracted by 13%. Cuts were sought in the public sphere. The agenda of privatization gathered strength, producing regulatory reforms. The discourse of liberalization advanced rapidly (see e.g., Sjögren & Fernler, Citation2019). It would not spare the legal status and the operations of Finnish car inspection – nor The Inspector:

Wild cuts were sought! They talked about 5% annual cuts in the number of our personnel. I could see myself that this was the triggering factor in the discussion that we started talking about becoming a commercial enterprise, as was the case with many state-owned organizations. It was the first step … In 1993 you started getting messages that the world was moving to the direction that this too would, one day, become a competitive industry. (H.J.)

The personnel’s reaction was that ‘Oh damn … Now we cannot (go on) … The big wheel turns!’ We had nothing to say in this … ‘Big shots’ take decisions, and you haven’t got much else than to try and adapt yourself. (M.L.)

It was this general change in society … Let’s allow competition, let’s allow competition! (M.S.)

Well, I don’t really know the root cause of this [competition] … But for its part this … Finland’s membership of the European Union (in 1995)! That is where it then came in. That in every sector, in every domain, we must have this ‘competition’! So there it was. This very turning point for changing car inspection practices as well – because this had been a full state monopoly for so long. (A.V.)

Competition means that the customer can choose: Do you come to us – or do you go somewhere else? So even the more hardheaded-one realizes that now it’s time to change ways of operating. (M.L.)

Let’ say that when this notion of competition came – or the fear of competition – so that is something that molds thinking. That you try to internalize how you should act here. (T.T.)

6.2. New Rules of the Game: The Discourse of The Customer

The inspectors were subject to normalizing training, carried out by trusted instructors – ‘men in black suits,’ as interviewee K.H. recalled. This aimed at a reorientation of thinking and behavior. New ‘rules of the game,’ a revised ‘natural way of doing things,’ was sought (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 631). The technically competent but authoritarian and whimsical state official would be replaced by a more appropriate worker. Established ways of making sense and acting were to become regulated.

The Customer stood as a key idealization within the new discourse. It was a destabilizing rhetorical medium in transforming self-presentation, calling for an urgent ‘identity project.’ It would uproot the perceptions of subordinates. Technical priorities and the powers of a public official would yield to a Customer-driven logic. This suggested radically revised standards in how car-owners were to be treated. A re-authoring of workplace selves was sought by the naturalization of the new ‘rules of the game’ around The Customer. A financial dependency that disturbed the self was emphasized: Salaries would no longer come from a budget, but from the market. For instance A.V. stated:

The Customer came forth … And when the company-mode (Ltd.) came a couple of years later, so there The Customer then came in. That it stood highest, on the top. And everybody else was lower, on the pyramid … The Customer pays the salary! It is not coming any more from the administration’s pocket.

So even the few stubborn-ones bended a little towards not speaking to The Customer in a harsh way any longer … And I guess, as we talked about and all knew actually, competition would arrive. And if you wish your job to go on, we thought that … Yes, most of us had that thought inside our heads, that now we do this thing differently!

6.3. Developing Skills: Resistant Selves

Besides redefining the rules of the game in car-inspection, the training program went further. It promoted a reorientation of grass-root action, calling for novel skills. ‘Men in black suits’ introduced a service- and sales-centered vocabulary, as well as prescribed new modes of action. The Inspector would now stand as an approachable, equal actor to the car owner. Argumentative skills in facing The Customer were introduced. The technical and authoritarian workplace identity, it was hoped, would fade into oblivion. The Inspector would act as an appropriate service-provider and suave salesman – also selling safety-enhancing products to The Customer. In these new capacities, equipped with competencies of polite persuasion, the re-authoring of the self became necessary. On these skills and the organizational ‘talk’ that accompanied them, an interviewee noted:

Yes, it was marketing and selling – they were the main thing. Nothing of this was present in the old system … Not a word of this was uttered there. Purely technical issues were discussed. (A.V.)

To me personally, to somebody who represented so fully the technical domain, these trainings meant more like suffering. Because they were like hullabaloo. Something that had nothing to do with the technical! So rather heavily I took it in the beginning … (H.O.)

Some people can do it. But not everybody can … When I then listened to these guys (the ‘men in black suits’), the counter-arguments started. ‘This takes time, goddamn, when you need to chat with them [the customers]’. Where do you take that time when you need to keep up with the pace? (H.M.)

I don’t know what I got out from it (the training). But there was for instance this selling of new products … And this is outright repulsive to us – to us old state officials – this kind of ‘selling’. Outright repulsive activity! Of course I cannot speak for the entire personnel, but we old state officials – who have been used to earning our living by working – we don’t like this kind of marketing spirit getting involved with inspection … That to some old grandpa, who still arrives trembling to the inspection – you should say ‘By the way, we have these safety grooves here!’ … I don’t like to go into this.

6.4. The Introduction of a Financial Knowledge

Operating as a limited liability company from the beginning of 1996, events continued to unfold at FMVI. A new knowledge was introduced: The stations became subject to systematic financial monitoring. In this financial knowledge, and in the introduction of operational knowledge (with non-financial measurements) later, our study uncovered the constitutive power of accounting: Accounting artifacts produced persistence, clarity, transparency and comparability as well as a sense of direction – and in so doing contributed to the reshaping of The Inspector’s subjectivity.

Traditional financial measurements were mobilized. As profit-centers, the stations became responsible for operational profit. Persistent profit-control – aligned with the discourse of The Customer – was instituted. Financial monitoring became ever-present and took place in real-time, extending deep into operations. Every day, it made visible realized local sales, costs and profitability. Speaking about how profitability is used to monitor the firm, the CFO described how alert he remained:

We can follow it on a daily basis. We get, next morning, the sales of a station. We get it on the level of the station. We get it on the level of products – volumes, average prices … I can look instantly there and say ‘OK, there they are above budget and that much money should, in principle, come in from that day then.’ (J.S.)

All the time, the computer picks up the information. And calculates percentages or whatever is wished. So control is – in this way – very intensive and specific. (M.S)

Well, the profit margin after general overheads. That is followed. Of course they follow costs … Market-shares are followed pretty strictly. (J.J.)

It (profitability) has been followed. And our personnel really has then an understanding of what is profitable … That how much money do we get from them? Everybody has a keen sense of that! (H.O.)

Responsibility was driven down to the station heads … Each year they became more and more involved with the making of budgets, and became committed to it in this way … They became, so to speak, profit-responsible. (H.J.)

If we know that some tools or something must be bought, we can do this. Of course larger purchases must be checked from headquarters … They do follow us. But I can say that much is under the glove of the station’s head. (V.R.)

That is the fundament, this. Where are you going? Otherwise you don’t have a direction where to go. It is an important thing. You should not disconnect the numbers from this. The numbers are important, after all. (O.R.)

So it (information system) gives you direction. You know at 10 am what you have done yesterday. (A.V.)

It’s difficult to know fully what goes on in people’s heads … I mean some amount of resistance is always there. But I would say that mostly this is taken positively and has been accepted. That the firm’s management has set this kind of targets – and then we try to meet them, to cope with them. (H.O.)

Today you have to be a businessman, who takes care of the station’s bottom-line. That in a competitive situation, the station reaches the bottom-line which has been agreed in the yearly budget-negotiations – and where the competitive situation has been taken into account. He should also follow the competitor’s moves, reach this agreed bottom-line and keep the customers, one way or another. And pretty ‘free hands’ then, in how he keeps these customers – as long as it fits our style. (P.H.)

If the station is not profitable, it does not make sense to keep it open … You have a lot of them, a lot of them (numbers). Numbers of course tell, I mean following them tells you, what happens in the house and how the work is done. That is it profitable? Or do we work just for the fun of it?

In practice we operate entirely on business-principles. That every inspection-business is a business that needs to get its own return from out there. Which means that this performance is measured in many ways, all the time. (T.M.)

In that way it brings ‘pressures’ that we should perform. That already, ‘There it comes – the paying customer!’ Or the one who pays your salary … (V.R.)

I do believe that station heads have pretty much internalized this. And I believe that most other workers as well … For instance in this ‘team’ around Seinäjoki [a town in Western Finland], every station in the ‘team’ (area) can watch everybody else. We can follow each other’s financial status, market-shares, rejection-ratios. We kind of ‘whip’ each other … (J.J.)

7. Into the ‘New World’ of the New Millennium

7.1. Operational Knowledge by 9-8-6-5: Performing for the ‘Total Score’

The reshaping of The Inspector’s identity continued as the organization entered the new millennium, implying considerable identity-work. First, the ‘A-Handbook’ was introduced: This was a detailed manual that guided internal operational audit, formalizing operational work. Second, systematic ‘Co-Pilot Auditing’ of stations was established. The knowledge from this micro-audit culminated in the quantification of a station’s operational performance in its ‘Total Score’ – translating qualities into quantity.

The Quality Manager (P.H.) recalled the inception of the ‘A-Handbook,’ the formalization and standardization of the often idiosyncratic work practices:

And then we would start looking at the things which were important from The Customer’s perspective. We found out that we had no manual anywhere … about how to take care and manage things. When we thought about the standards of the [station’s] evaluation, we understood that no manual was there … That is how we came to this manual – which we smartly called the A-Handbook.

The A-Handbook tries to stand as a model of how to behave, in our view, so that ‘The Customer’ is as happy as s/he can be. So we make sure that irrespective of which station The Customer visits, the service is always the same. (J.S.)

The A-Handbook connected key operational processes with The Customer, offering behavioral templates. These were to transform work into appropriate ‘service.’ By reframing practical concerns as ‘service,’ it destabilized self-perceptions. The prescribed operational action was, however, received without significant identity struggle. It offered reassuring scripts for ‘everyday action’ at work:

At least most of us have liked it … When you don’t know everything; it’s easy to look from there (the A-Handbook). How should this be done? (J.J.)

And this thing works as follows: When we have gone through all these evaluations, we then calculate an average from the A’s, B’s, C’s and D’s … This is translated into numbers … These are added up, these numbers. In such a way – a bit like in a Formula One race and other [races] – in a way that from a good ‘grade’ you get better points. That it is not linear. The points are 9-8-6-5. (emph. added)

The fundamental principle is that we strive towards conformity in our operational sites. It’s a bit like this McDonald’s-thinking. That wherever in the world you walk into a McDonald’s, you know approximately what you get there. That is wherefrom we copy this thinking. And we have then this Co-Pilot who comes from another operational location, and usually from another region, to check the situation here. (H.O.)

This is a relief, in a way. That you have clearly … That some people have done the thinking. That you don’t have to think yourself about everything, take a stand, wonder about it – and solve it yourself. That you get much of it as given … That so many of the basic things have been standardized. We have made it easier. If you overstate a bit you could say that the head of station has an excellent opportunity to concentrate on the essential. In my view, it is actually an ideal situation. That these guidelines, they are not experienced as constraining. It should not be – that it leaves room to play within a frame … That the frame is similar. You don’t have to think much of it, but execute it and act … (J.S.)

In my opinion it has been well received by personnel and superiors this Co-Pilot thing. It’s a bit of a miracle – but this is really so … It [the A-Handbook] is an instrument of control, how these operations are being controlled. And the best things have been included from our own organization. (O.R.)

The greatest change was that you could start thinking with your own brain. The customer service perspective came into these matters. That you could start serving the customer? So it did not immediately … You could not yourself believe it – to be true! (H.J.)

When we deal with these customers every day here, so … I know every day where we are going. That one audit, once a year, does not give me any ‘Aha!’-revelations, that ‘Aha – this is how it is!’ First of all, I think that it is my job to know that daily. Where are we going? Is our customer service on the right level?

I don’t think that ‘statistics’ is important. The Customer who comes in is important! (M.S.)

8. Discussion and Conclusions

This empirical account of can be summarized on three interpretive dimensions, suggesting how the subjectivity is theorized as a contrast between two embedded identities at the workplace, adding to our body of knowledge (Brown, Citation2019, Citation2015; Watson, Citation2008). First, we underline the context of the self. The ‘Old World’ was a semi-closed ‘private’ cocoon: Life was predictable, non-scripted and contained little comparability. Informal practices prevailed, relying much on tacit operational knowledge. The management process involved few numbers. But The ‘New World’ is a more unpredictable transparency. It runs on numerous scripts. Comparability is established. Practices are largely formalized and build less on tacit knowledge. Knowledge is more explicit, and the management process involves a multitude of financial and operational ‘numbers.’

The second dimension combines self-positioning and self-presentation. An asymmetrical positioning characterized the self in encounters of the ‘Old World.’ Car owners were subordinates. Being an empowered public official, and acting as an expert with technical priorities, were sources of self-respect. A dependency from the state predominated. This contributed to a stabilized self-presentation. In the ‘New World,’ self-positioning is more egalitarian. Self-respect is earned every day, in a commitment to profitability and service. Technical priorities co-exist with pressing commercial ones, which destabilizes self-presentation – moving it towards projecting the self also as a ‘businessman.’ The dependency from The Customer, in a capricious market, is evident.

Forms of self-actualization, how work suggests a meaning, and what insecurities inhabit subjectivity merge into the third dimension whilst contrasting workplace selves. In the ‘Old World’ self-actualization was enabled by authority and suggested the exercise of power. Some ambivalence was, however, present when the self was seeking expression: Leeway and discretion were allowed in how work was carried out; its quality varied. On the other hand, self-actualization in any broader initiative took place within very narrow limits. Meaning was status-related. Work was an expression of status – and the duty that stemmed from status. And few insecurities overshadowed the dignity of the self.

Identity in the ‘New World’ is situated in a different way. Self-actualization within operational work processes is bound by formalized limits; the quality of work is relatively standardized. But self-actualization can be sought with other means, in initiatives addressing the wider contingencies of work. Meaning derives from ‘performance’ in celebrated service-work: This moves towards being synonymous with appropriate ‘performance.’ But meaning at work also originates from subjectivity being sensitive to opportunities in ‘business.’ This fluidity offers the self the possibility of ‘micro-emancipation’ (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation1996, Citation2002, p. 624). Finally, identity at the workplace is now surrounded by new insecurities. These relate to vagaries of the market and job security – suggesting a more vulnerable, precarious self. This contrast can be illustrated in Table .

Table 1. Old and new identities at FMVI

Taking theorizing further, we wish to revisit the study’s anchoring in the regulation of identity. The investigation has gone beyond the role of discourse: It illustrated how discursive elements and the constitutive power of accounting became mobilized together – in what was coined as the Great Alliance of words and measurements, financial as well as operational. As with every field study, beyond understanding a particular context, the question remains: How is this interpretation significant, setting empirical nuances aside? The theoretically intriguing question runs as follows: What is the mechanism of the Great Alliance – how do measurements ‘amplify’ discourse in identity regulation? Here, the study fleshes out the power of accounting in the production of what is explained below.

We begin by the production of persistence. As illustrated, accounting measurement becomes an integral part of everyday work. Measurement is a tireless reminder of discursive aspirations. The systematic, ever-present and intensive nature of measurement knits discourse deeply into the texture of work – and into time, as it flows from one day to the next. With regularized measurement, the self remains alert – beyond passing ‘educational’ events, in a constant awareness of what discourse suggests, what it requires today. And the disciplinary implications of discourse ‘stick’ better to subjectivity with the persistence of measurement in the micro-contexts where selves are nested. Measurement is a persistent technology for regulating the self.

Second, the study points at the production of clarity. For the self in the midst of work, discourse may appear as an ambiguous, idealized conceptual assemblage. Instead of providing practical answers to practical questions, discourse can mystify more than it clarifies. Circumstances around the self appear as more complex and volatile – as was illustrated with the arrival of The Customer. What is expected at the workplace, how should discursive, new ‘rules of the game’ actually become enacted at the grass-root level? Conflicting interpretations of programmatic prescriptions abound; anxiety and fragmentation of identity may follow. With measurement, a sense of clarity is restored: Accounting translates discourse into legitimate, concrete and ‘hard’ reference points which become enacted – regulating identity by reassuring the coherence of the self.

Third, measurement suggests the production of transparency and comparability. With the introduction of financial and operational knowledge, the self is brought under the gaze of normalizing measurement. Accounting measurement is a potent vehicle in forcing a re-evaluation of subjectivity. It maintains self-awareness as a visible subject – uprooting the self from ‘privacies.’ The transparency of measurement suggests incessant evaluation of how the self is aligned with discursive imperatives. This transparency at the workplace corrects the self, removes eccentricities and urges self-restraint, even in the absence of management intervention. Moreover, transparency regulates subjectivity at work by introducing comparability. This marginalizes any remaining self-containment. A sense of relativity – a quantified comparison of how ‘significant others’ fare en route to discursively underpinned objectives – becomes a naturalized dimension of the self.

Accounting measurement is, however, also engaged with the regulation of the self in the production of direction. Striving towards objectives laid out within discursive regimes, the self is motivated by a sense of progress. Measurement provides reaffirming evidence of incremental advancement: How do I proceed? It builds a legitimate record of personal ‘improvement,’ signs of appropriate self-actualization in the prescribed work involving the self. Doing so, measurement validates the direction itself. It produces ontological security and commitment towards a specific direction. It consolidates the reorientation of the self, the worker’s ‘inside,’ towards discursively communicated objectives.

The study’s interpretation of events has followed our foremost method theory in identity regulation, as suggested by Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002): It addressed the context of the worker, as well as the framing of the worker’s action orientation. The study’s findings seek to contribute to this theoretically established framework – refining it further. They corroborate the significance of discourse, illustrating how discourse redefined the Zeitgeist, the worker’s broad context. The study also showed how discourse reoriented the worker’s self-image, by introducing new ‘rules of the game.’ Discourse also influenced the re-authoring of the worker’s action orientation, in fostering new skills.

However, what knowledge suggested – and how that knowledge came to regulate the worker’s action orientation and subjectivity – yielded a central theoretical contribution. The study goes beyond the central role of discursive resources in theorizing identity regulation (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002; Bardon et al., Citation2017; Clarke et al., Citation2009; Kornberger & Brown, Citation2007; Sveningsson & Alvesson, Citation2003; Watson, Citation2008). Knowledge is not to be understood, we argue, as a purely discursive phenomenon. Knowledge indeed defines the knower and frames who one is (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 630). But this knowledge can be a powerful, non-discursive one. In this study, knowledge meant quantitative knowledge – accounting measurement, with both financial and operational measures (Vaivio, Citation2006, Citation1999). And as to why quantitative knowledge was effective in regulating identity, in producing the appropriate worker, we refer to the constitutive role of accounting measurement within the Great Alliance – accounting’s potential in the production of persistence, clarity, transparency and comparability, as well as direction.

The study’s emphasis of quantitative knowledge in identity regulation raises yet another consideration. Since the worker is not a passive receptor of promoted discourses but critically interprets and contests these, identity is far from being fully malleable (Alvesson & Willmott, Citation2002, p. 628). Resistant selves appear, as personified by the worker who looked at ‘selling’ with notable distrust (Collinson, Citation2003, pp. 539–541). How the introduction of quantitative knowledge proceeded in the chronology of this study’s empirical events suggests, nevertheless, that accounting measurement can assist the worker in accommodating a revised self-presentation. Within the Great Alliance, in the partnership between words and numbers, the constitutive power of accounting – especially by producing clarity as well as direction – has an important role to play in alleviating the antagonisms and tensions, which accompany radical revisions of identity. Accounting, we argue, is present in the intricate mechanisms of identity work – bridging discourse and the construction of the self (see Watson, Citation2008).

Our findings extend discourse-related accounting studies on identity. A similar process of normalization was uncovered, where discursive imperatives and calculative practices played key roles, as described by Covaleski et al. (Citation1998): Their firm sought to transform expert identities of Big Six partners – high on the organizational echelon – with the rhetorical elements of management programs and financial targets. However, at FMVI, also operational measurements of performance and micro-audit (e.g., Kaplan & Norton, Citation2007; Bogetoft, Citation2012) became mobilized for uprooting ‘privacies’ of shop-floor workers. But our observations on resistant selves are aligned with Covaleski et al. (Citation1998). The worker was not malleable without tension.

This study depicted discursive turbulence where identity is under threat. As pointed out by Gendron and Spira (Citation2010), ensuing identity work patterns and the reflective acts of individuals (on discourse) can be characterized also by the fragility of the self and disillusion – a sense of powerlessness and incapacity. Relying on our empirical narrative, we wish to argue as follows: Especially the production of persistence, clarity and direction with accounting measurement can assist the translation of stylized, often confusing discourses in reflective acts that transform the self. The Great Alliance can alleviate the disillusionment of the self – and instead foster hopefulness, a relative degree of optimism regarding the future (Gendron & Spira, Citation2010, p. 293). However, on a critical undertone, this study also resonates with what Gendron (Citation2008) suggests on normalizing academic identity representations with performance measures, contributing to superficiality and conformity. Our argument also leads to reservations and questions regarding the production of transparency and comparability: Will the more visible and ‘benchmarked’ appropriate worker, following blueprints carried by the Great Alliance, show less initiative, avoid experimenting, become averse to any ‘risk’ in the workflow? The specter of shop-floor identity that stifles innovation and renewal could become a real concern.

The paper speaks to how discursively propagated, ideational storyable items on aspirational role models are regulating identity work (Goretzki & Messner, Citation2019). Here, we underline what has been said on frontstage interactions of management accountants: In these encounters idealized identity, like the template of a ‘business partner’ crafted on the backstage, becomes enacted and negotiated with organizational actors. We wish to highlight that carrying often abstract, vague role models into the front stage can benefit from a close alliance between words and numbers. Going beyond the shopfloor worker of our study, The Great Alliance could assist in confirming and stabilizing an idealized expert identity, making it more valid and actionable: Also management accountants’ identity projects, built upon discursive aspirations and the powerful rhetoric of management agendas, e.g., in New Public Management or in narratives of ‘partnership’ (see Järvinen, Citation2009; Morales, Citation2019), may benefit from more systematic, tangible work-related measurements – especially from measures which clarify and give direction on how to translate often fuzzy professional role models of accountants into practice.

The Great Alliance is also related to discussions on calculative practices in ‘hybrid’ organizations: Professionals in healthcare, knowledge-intensive public organizations and universities have seen their work transformed by ‘accountingisation’ and the discourse of New Public Management (e.g., Grossi et al., Citation2020; Kurunmäki, Citation2004; Miller et al., Citation2008; Sjögren & Fernler, Citation2019). Besides studies in management accountants’ identity projects, future investigation on identities of educated knowledge-workers could draw more broadly from our study’s perspective on quantifying work in identity regulation: Are our findings from the shop-floor transportable to the shaping of intricate professional and managerial identities in ‘hybrid’ work, higher on the organizational echelon?

As stated from the outset, identity regulation is a medium of control. Hence, we also introduce new insight into conceptualizations of management control as a package and a system (e.g., Bedford et al., Citation2016; Grabner & Moers, Citation2013; Malmi & Brown, Citation2008; Merchant & Van der Stede, Citation2007). As important interdependencies exist between management control elements, in different configurations, mobilizing quantitative knowledge is not a technical instance of standalone results control. If numbers are a vehicle in shaping the subjectivity of the worker, The Great Alliance has a bearing on e.g., cultural controls, on the values and symbols cherished by the worker as well as on social, human resource-related ‘personnel’ controls (Pfister & Lukka, Citation2019). Questions arise regarding familiar administrative controls, like formalized operational procedures (Malmi & Brown, Citation2008) and detailed action controls (Merchant & Van der Stede, Citation2007) – once they become coupled with quantitative knowledge that ‘amplifies’ discourse: What are their implications on workplace identities? How are effects on the appropriate worker’s subjectivity resonating in overlapping management control systems? This adds to considerations on complementarities between social and technical forms of control which feed and inform each other, for instance in a ‘socio-technical dyad’ (Gerdin, Citation2020). More should be known on how to identify and balance tensions between interacting discursive and quantitative elements of management control (Van der Kolk et al., Citation2020).

We acknowledge the theoretical and empirical limitations of the study. It builds on acknowledged perspectives on identity and its regulation, as well as on key accounting studies relating identity with discourse. Empirically, as stated earlier, identity is slippery concept, difficult to operationalize in data collection. We studied the worker’s identity as it surfaced indirectly – in interviews that focused on work, reflecting an underlying identity.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the study have been presented in many conferences and workshops; we sincerely acknowledge the numerous constructive comments and suggestions we have received on these forums. We are also indebted to Teemu Malmi, Seppo Ikäheimo, Jari Huikku as well as Jan Mouritsen for their suggestions on how to proceed with our argument. Further, we thank the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback and suggestions. Finally, we wish to thank Teppo Sintonen for his insights and his valuable input on a previous version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The nine categories discussed by Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002, pp. 629–632) are: (1) defining the person directly, (2) defining a person by defining others, (3) providing a specific vocabulary of motives, (4) explicating morals and values, (5) knowledge and skills, (6) group categorization and affiliations, (7) hierarchical location, (8) establishing and clarifying a distinct set of rules of the game and (9) defining the context.

References

- Abrahamsson, G., Englund, H., & Gerdin, J. (2011). Organizational identity and management accounting change. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 24(3), 345–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571111124045

- Ahrens, T., & Dent, J. (1998). Accounting and organizations: Realizing the richness of field research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10(1), 1–39.

- Alvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (1996). Making sense of management – a critical analysis. Sage.

- Alvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (2002). Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies, 39(5), 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305

- Ashforth, B., & Schinoff, B. (2016). Identity under construction: How individuals come to define themselves in organizations. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062322

- Bardon, T., Brown, A., & Pezé, S. (2017). Identity regulation, identity work and phronesis. Human Relations, 70(8), 940–965. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716680724

- Bedford, D., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.04.002

- Bogetoft, P. (2012). Performance benchmarking – measuring and managing performance. Springer.

- Brown, A. (2015). Identities and identity work in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12035

- Brown, A. (2019). Identities in organization studies. Organization Studies, 40(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618765014

- Brown, A., & Humphreys, M. (2006). Organizational identity and place: A discursive exploration of hegemony and resistance. Journal of Management Studies, 43(2), 231–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00589.x

- Burchell, S., Clubb, C., Hopwood, A., & Hughes, J. (1980). The roles of accounting in organizations and society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 5(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(80)90017-3

- Chambers, A., & Rand, G. (2010). The operational auditing handbook: Auditing business and IT processes (2nd ed.). Wiley & Sons.

- Clarke, C., Brown, A., & Hailey, V. (2009). Working identities? Antagonistic discursive resources and managerial identity. Human Relations, 62(3), 323–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708101040

- Collinson, D. (2003). Identities and insecurities: Selves at work. Organization, 10(3), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084030103010

- Covaleski, M., Dirsmith, M., Heian, J., & Samuel, S. (1998). The calculated and the avowed: Techniques of discipline and struggles over identity in Big Six public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(2), 293–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393854

- Deetz, S. (1995). Transforming communication, transforming business: Building responsive and responsible workplaces. Hampton Press.

- Dent, J. (1991). Accounting and organizational cultures: A field study of the emergence of a new organizational reality. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(8), 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(91)90021-6

- Down, S., & Reveley, J. (2009). Between narration and interaction: Situating first-line supervisor identity work. Human Relations, 62(3), 379–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708101043

- Dyer, W., & Wilkins, A. (1991). Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. The Academy of Management Review, 16(3), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.2307/258920

- Empson, L. (2004). Organizational identity change: Managerial regulation and member identification in an accounting firm acquisition. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 759–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2004.04.002

- Englund, H., & Gerdin, J. (2019). Contesting conformity: How and why academics may oppose the conforming influences of intra-organizational performance evaluations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(5), 913–938. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2019-3932

- Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish. Penguin.

- Franceschini, F., Galetto, M., & Maisano, D. (2007). Management by measurement – designing key indicators and performance measurement systems. Springer.

- Gagnon, S., & Collinson, D. (2014). Rethinking global leadership development programmes: The interrelated significance of power, context and identity. Organization Studies, 35(5), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613509917

- Gendron, Y. (2008). Constituting the academic performer: The spectre of superficiality and stagnation in academia. European Accounting Review, 17(1), 97–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180701705973

- Gendron, Y. (2015). Accounting academia and the threat of the paying-off mentality. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 26, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2013.06.004

- Gendron, Y., & Spira, L. (2010). Identity narratives under threat: A study of former members of Arthur Andersen. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(3), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.09.001

- Gerdin, J. (2020). Management control as a system: Integrating and extending theorizing on MC complementarity and institutional logics. Management Accounting Research, 49, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2020.100716

- Gioia, D., & Patvardhan, S. (2012). Identity as process and flow. In M. Schultz, S. Maguire, A. Langley, & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), Constructing identity in and around organizations (pp. 50–62). Oxford University Press.

- Goretzki, L., & Messner, M. (2019). Backstage and frontstage interactions in management accountants’ identity work. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 74, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.09.001

- Gotsi, M., Adriopoulos, C., Lewis, M., & Ingram, A. (2010). Managing creatives: Paradoxical approaches to identity regulation. Human Relations, 63(6), 781–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709342929

- Grabner, I., & Moers, F. (2013). Management control as a system or a package? Conceptual and empirical issues. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(6–7), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.09.002

- Grossi, G., Kallio, K.-M., Sargiacomo, M., & Skoog, M. (2020). Accounting, performance management systems and accountability changes in knowledge-intensive public organizations – a literature review and research agenda. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 33(1), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-02-2019-3869

- Hardy, C., & Thomas, R. (2014). Strategy, discourse and practice: The intensification of power. Journal of Management Studies, 51(2), 320–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12005

- Hopwood, A. (1983). On trying to study accounting in the contexts in which it operates. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 8(2–3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(83)90035-1

- Hopwood, A. (1986). Management accounting and organizational action: An introduction. In M. Bromwich & A. Hopwood (Eds.), Research and current issues in management accounting (pp. 9–30). Pitman.

- Järvenpää, M., & Länsiluoto, A. (2016). Collective identity, institutional logic and environmental management accounting change. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 12(2), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-11-2013-0094

- Järvinen, J. (2009). Shifting NPM agendas and management accountants’ occupational identities. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22(8), 1187–1210. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570910999283

- Kakkuri-Knuuttila, M.-L., Lukka, K., & Kuorikoski, J. (2008). Straddling between paradigms: A naturalistic philosophical case study on interpretive research in management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(2–3), 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.12.003

- Kaplan, R., & Norton, D. (1992). The balanced scorecard – measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71–79.

- Kaplan, R., & Norton, D. (1996). The balanced scorecard. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R., & Norton, D. (2007). Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 150–161.

- Keating, P. (1995). A framework for classifying and evaluating the theoretical contribution of case research in management accounting. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 7(Fall), 66–86.

- Kenny, K., Whittle, A., & Willmott, H. (2011). Understanding identity and organizations. Sage.

- Kornberger, M., & Brown, A. D. (2007). ‘Ethics’ as a discursive resource for identity work. Human Relations, 60(3), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707076692

- Kurunmäki, L. (2004). A hybrid profession – the acquisition of management accounting expertise by medical professionals. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(3–4), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(02)00069-7

- Lambert, C., & Pezet, E. (2011). The making of the management accountant – becoming the producer of truthful knowledge. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(1), 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2010.07.005

- Liebfried, K., & McNair, C. (1992). Benchmarking: A tool for continuous improvement. Harper Business.

- Lukka, K., & Modell, S. (2010). Validation in interpretive accounting research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(4), 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.10.004

- Lukka, K., & Vinnari, E. (2014). Domain theory and method theory in management accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(8), 1308–1338. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1265

- Lyotard, J.-F. (1979). La condition postmoderne [The postmodern condition]. Les Éditions de Minuit.

- Malmi, T., & Brown, D. (2008). Management control systems as a package – opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2008.09.003

- Mantere, S., & Vaara, E. (2008). On the problem of participation in strategy: A critical discursive perspective. Organization Science, 19(2), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0296

- McKinnon, J. (1988). Reliability and validity in field research: Some strategies and tactics. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 1(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004619

- Merchant, K., & Van der Stede, W. (2007). Management control systems (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Miller, P. (1994). Accounting as social and institutional practice: An introduction. In A. Hopwood & P. Miller (Eds.), Accounting as social and institutional practice (pp. 1–39). Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, P., Kurunmäki, L., & O’Leary, T. (2008). Accounting, hybrids and the management of risk. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7–8), 942–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.02.005

- Miller, P., & O’Leary, T. (1987). Accounting and the construction of the governable person. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(3), 235–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(87)90039-0

- Miller, P., & O’Leary, T. (1994). Accounting, ‘economic citizenship’ and the spatial reordering of manufacture. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(1), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(94)90011-6

- Morales, J. (2019). Symbolic categories and the shaping of identity – the categorisation work of management accountants. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 16(2), 252–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-06-2018-0040

- Morales, J., & Lambert, C. (2013). Dirty work and the construction of identity. An ethnographic study of management accounting practices. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(3), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.04.001

- Pfister, J., & Lukka, K. (2019). Interrelation of controls for autonomous motivation: A field study of productivity gains through pressure-induced process innovation. The Accounting Review, 94(3), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52266

- Scapens, R. (1990). Researching management accounting practice: The role of case study methods. British Accounting Review, 22(3), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-8389(90)90008-6

- Schultz, M., Maguire, S., Langley, A., & Tsoukas, H. (2012). Constructing identity in and around organizations. In M. Schultz, S. Maguire, A. Langley, & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), Constructing identity in and around organizations (pp. 1–20). Oxford University Press.

- Sjögren, E., & Fernler, K. (2019). Accounting and professional work in established NPM settings. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(3), 897–922. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2015-2096

- Sornikivi, U.-M. (1996). Yhdeksän vuosikymmentä liikenteen turvallisuutta – ajoneuvojen rekisteröinti, katsastus ja kuljettajien tutkiminen [Nine decades of motoring safety: The registration, inspection and driver examination of motor vehicles]. Autorekisterikeskus, Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy.

- Sveningsson, S., & Alvesson, M. (2003). Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Human Relations, 56(10), 1163–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035610001

- Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self. The making of the modern identity. Harvard University Press.

- Vaivio, J. (1999). Examining ‘the quantified customer’. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(8), 689–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(99)00008-2

- Vaivio, J. (2006). The accounting of ‘the meeting’: Examining calculability within a ‘fluid’ local space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(8), 735–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2005.12.007

- Vaivio, J. (2008). Qualitative management accounting research: Rationale, pitfalls and potential. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 5(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/11766090810856787