?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

I develop a model that provides new insights into the consequences of the provision of non-audit services (NAS) by audit firms to audit clients. I also investigate the joint implications of NAS and contingent audit fees (CAF) for audit quality. In the model, litigation and reputation costs do not provide sufficient incentives to auditors to exert audit effort. Investors of client firms may therefore let auditors provide NAS because of an incentive effect. Indeed, the possibility of providing NAS contingent on detecting financial misstatements increases auditors' incentives to exert audit effort. However, the provision of NAS also reduces auditor independence, which may decrease audit quality and in turn render the provision of NAS by auditors undesirable. Thus my analysis uncovers an interesting tradeoff for regulators between the positive incentive effect and the decrease in auditor independence. Removing the current restrictions on CAF may offset the ex post decrease in audit quality while preserving the ex ante incentives. My analysis also generates a number of testable empirical predictions.

1. Introduction

What are the incentive effects of the provision of non-audit services (NAS) on auditors? This important policy question is of concern to regulators given the debate that has been raging for years on whether audit firms should provide NAS to audit clients. This debate is often reduced to a simple cost and benefit tradeoff. On the one side, joint NAS and audit services provision is likely to be more efficient in terms of production costs because of knowledge spillovers (Simunic, Citation1984). On the other side, NAS may threaten auditor independence because it creates an economic bond between the auditor and the client (DeAngelo, Citation1981a). In the absence of a clear sense of the incentive effects, the conventional wisdom that ‘providing both NAS and audit services to the same client threatens auditor independence and may affect audit quality’ seems to prevail (Causholli et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, Ewert (Citation2004) emphasizes that ‘the incentive problems of combining NAS and auditing are still an open issue’. More recently, auditor independence rules related to NAS appear to be headed in opposite directions in the USA and in the UK, which indicates a disagreement among regulators (CFO, Citation2020).Footnote1 I believe that a proper understanding of the incentive effects of NAS would guide regulators in designing new regulatory actions.

In this paper, I depart from the conventional wisdom and analyze a novel tradeoff related to the provision of NAS by auditors to audit clients. I also investigate the joint implications of NAS and contingent audit fees (CAF) for audit quality. Specifically, I build a framework that highlights a positive incentive effect of NAS: the possibility of providing NAS contingent on detecting financial misstatements may increase the auditor's effort to detect those misstatements. This represents a benefit of the provision of NAS by auditors. Nonetheless, my analysis also underlines that the provision of NAS reduces auditor independence and may decrease audit quality, which I define as the conditional probability that an auditor detects and reports financial misstatements. In a setting with a single firm, there is no role for regulation as investors trade off the cost and benefit of using NAS to provide effort incentives to the auditor. However, in the presence of multiple firms, I highlight the negative externalities caused by the decrease in audit quality when investors rely on peer-firms' financial statements to make investment decisions. Restricting auditors from providing NAS may then be desirable. Thus regulators face a tradeoff between the ex ante positive incentive effect and the ex post decrease in auditor independence. Removing the current restrictions on CAF for unfavorable audit opinions may offset the ex post decrease in audit quality while preserving the ex ante incentives.

Litigation and reputation costs are considered to be the main market-based incentive forces that drive audit quality (e.g., Skinner & Srinivasan, Citation2012; Venkataraman et al., Citation2008). However, the series of scandals at companies such as Enron, Worldcom, or, recently, Thomas Cook, are examples for which market-based incentive forces were not effective enough to prevent audit firms from giving clean audit opinions to fraudulent financial reports. DeFond and Zhang (Citation2014) claim that ‘it is unsettled whether reputation concerns play an important role in motivating auditors’ and that higher litigation risks may lower audit quality and/or be socially suboptimal. This paper highlights how the incentive effect of NAS, above and beyond litigation and reputation costs, can increase audit effort. Given the tradeoff between incentive effect and auditor independence, this paper provides conditions under which the provision of NAS increases or decreases investors' surplus and shows that there may be some role for introducing audit fee contingencies that supplement the structure of penalties that arise from legal liability.

My theory starts with a standard conflict of interests within two firms. The two firms are ex ante identical and have the same type, which can be either good or bad. The situation faced by each firm is as follows. The manager enjoys private benefits from running the firm and always sends the auditor a favorable report for attestation, so that the investor invests in the firm, which is suboptimal if the firm is bad. The auditor must exert a costly audit effort to increase the probability of detecting financial misstatements and then decides whether to report the misstatements to the investor. If the auditor does not report misstatements, the investor invests in the firm, and the manager hires a consultant to increase the firm's value. The consultant, who can be either the auditor or an outsider, earns a rent from the NAS contract. If the auditor detects misstatements, the manager exerts pressure on the auditor with the NAS contract so that the auditor hides the misstatements and makes a favorable audit report. The audit committee maximizes the investor's utility and designs an incentive mechanism to provide effort incentives to the auditor. In particular, the audit committee chooses audit fees and sets the probability that the manager succeeds in exerting pressure on the auditor (e.g., with corporate governance measures).

Firms often learn from other peer-firms' disclosures in making investment decisions (Roychowdhury et al., Citation2019). To capture those externalities, I consider a sequential game in which, firm 1 moves first and firm 2 follows. Thus auditor 1 first makes a report and investor 1 makes the investment decision for firm 1. Then, investor 2 observes investor 1's investment decision, auditor 2 makes a report, and investor 2 makes the investment decision for firm 2. I start by studying an unregulated economy without restriction on the provision of NAS and on CAF. The incentive mechanism that maximizes investor 1's surplus rewards auditor 1 for detecting financial misstatements. Providing effort incentives with the NAS rent is cheaper than providing incentives with CAF as long as the NAS value is large. More specifically, if auditor 1 detects misstatements, audit committee 1 optimally lets manager 1 give the NAS contract to auditor 1 with some probability. The expected NAS rent then provides incentives to auditor 1 to exert audit effort ex ante. Interestingly, having a fully independent auditor is suboptimal because such an auditor would never accept to misreport to get the NAS contract. There is no role for regulation in a setting with a single firm as audit committee 1 sets the optimal incentive mechanism and trades off the cost and benefit of using NAS to provide effort incentives to auditor 1.

I then solve for the incentive mechanism set by audit committee 2. Investor 2 observes auditor 1's report and investor 1's investment decision. If auditor 1 detects financial misstatements and makes an unfavorable audit report, it is publicly known that both firms are bad, and investor 2 does not invest in firm 2. Otherwise, if auditor 1 makes a favorable report, there is uncertainty about firm 2's type. If auditor 1's report is noisy, audit committee 2 provides incentives to auditor 2 to exert audit effort in the same vein as audit committee 1. In particular, if auditor 2 detects misstatements, audit committee 2 lets manager 2 give the NAS contract to auditor 2 with some probability. Otherwise, if auditor 1's report is sufficiently informative, audit committee 2 does not provide effort incentives to auditor 2, and investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1, i.e., there is herding behavior.

In the sequential equilibrium, the precision of auditor 1's report is important because investor 2 may also rely on auditor 1's report to make the investment decision. In particular, a decrease in the precision of auditor 1's report may lead to two negative externalities because investor 1 does not internalize the impact of the incentive mechanism for auditor 1 on investor 2's surplus. First, if auditor 1's report is sufficiently informative, the provision of NAS by auditor 1 leads to inefficient herding behavior. Indeed, investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1 and, in particular, if manager 1 exerts pressure on auditor 1, both investor 1 and investor 2 invest in bad firms. This is an inefficient investment externality. Second, the provision of NAS by auditor 1 reduces the reliability of auditor 1's report and may force investor 2 to incur the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2. This is an inefficient informational externality. Those two negative externalities create a role for regulation in this sequential game.

Next, I study a regulated economy in which the regulator may restrict the provision of NAS to audit clients. The regulator imposes a cap on the NAS rent that auditors can get from audit clients. I formally define audit quality as the probability that an auditor makes an unfavorable audit report to a bad firm, i.e., the probability that an auditor detects misstatements in a bad firm (audit effort) multiplied by the probability that an auditor reports misstatements (auditor independence). In this setup, the impact of NAS restrictions on audit quality is unclear. On the one hand, allowing auditors to provide both NAS and auditing services increases ex ante audit effort. On the other hand, if auditors are banned from providing NAS to audit clients, auditors are fully independent because managers cannot ex post exert pressure on the former with an NAS contract.

If CAF are disallowed, the regulator does not restrict the provision of NAS to audit clients because this restriction prevents investors from providing effort incentives to auditors. However, if CAF are allowed, the regulator may restrict the provision of NAS to audit clients. NAS restrictions force investors to use CAF to provide effort incentives to auditors. Thus NAS restrictions increase auditor independence and audit quality, making auditor 1's report more reliable and eliminating the negative externalities resulting from the provision of NAS. As in Kornish and Levine (Citation2004), investors can recover truth-telling if the provision of NAS by auditors is banned and CAF for unfavorable audit reports are allowed.

The results of this paper contribute to both the regulatory and academic communities. Regulators and practitioners fear that auditors would be unwilling to challenge a client if a negative audit opinion would mean losing future NAS contracts (e.g., Bell et al., Citation2015). As underlined by DeFond et al. (Citation2002), auditors are willing to sacrifice their independence if reputation and litigation costs associated with audit failures are smaller than the economic rents from NAS. The recent accounting scandals are examples of ex post conflicts of interest. However, regulators seem to focus on the ex post lack of auditor independence without considering the ex ante incentive effects. My findings shed some light on the desirability of the provision of NAS to audit clients and suggest regulators may need to investigate more carefully the tradeoff between ex ante incentives and an ex post decrease in auditor independence. In particular, I show that having fully independent auditors may not always be optimal.

Regulators have banned CAF in most jurisdictions. However, CAF could be used to provide incentives to auditors to exert audit effort in environments in which market-based incentive forces are not sufficient. My results show that removing the current restrictions on contingent audit fees jointly with banning non-audit services may increase auditor independence while preserving the ex ante effort incentives.

Finally, my model also generates several testable empirical predictions. The main empirical takeaway is that a positive relationship between NAS fees and financial misstatements does not necessarily imply NAS negatively affect audit effort and audit quality. On the contrary, I show that a positive relationship may indicate incentives are provided to auditors using NAS, and this mechanism improves ex ante audit effort and audit quality.

1.1. Related Literature

A large strand of the auditing literature studies the economic consequences of the provision of NAS by auditors to audit clients. In a seminal paper, Simunic (Citation1984) argues that auditors should provide NAS to audit clients because of knowledge spillovers between audit services and NAS. DeAngelo (Citation1981a) shows that NAS may threaten auditor independence because of an economic bond between the auditor and the client. Dopuch et al. (Citation2004) demonstrate that the presence of contingent rents from NAS is not sufficient for auditors to compromise their independence. More recently, Friedman and Mahieux (Citation2021), in a setting with multiple client firms, study how the potential to provide both auditing services and NAS, competition in the NAS market, and regulatory bans on the provision of NAS affect audit quality and social welfare. In this paper, I highlight a positive incentive effect of NAS and analyze the tradeoff between the incentive effect and the decrease in auditor independence.

Many empirical studies have been conducted to study the link between NAS and audit quality, and the evidence is mixed. Studies using output-based proxies find that NAS do not impair audit quality (e.g., DeFond et al., Citation2002; Krishnan et al., Citation2005; Schmidt, Citation2012), and some NAS may even improve it (e.g., Kinney et al., Citation2004), whereas studies using perception-based proxies find that investors penalize companies purchasing NAS (e.g., Frankel et al., Citation2002; Higgs & Skantz, Citation2006; Khurana & Raman, Citation2006). The main empirical challenge is to find a good proxy to measure audit quality and to identify the counterfactual observations (Carcello et al., Citation2020). My model predicts a positive relationship between NAS and audit effort. More importantly, it also predicts that, in the current legal environment without CAF, a ban on the provision of NAS by auditors would increase auditor independence but decrease audit quality.

Another branch of the auditing literature studies the economic consequences of CAF. Baiman et al. (Citation1987) analyze the role of auditing in a principal-agent context with an auditor and characterize the optimal contract with contingent fees between the principal and the auditor. Beeler and Hunton (Citation2002) and Dye et al. (Citation1990) argue that CAF may induce auditors to issue estimates different from their best personal estimates. Kornish and Levine (Citation2004) find that removing the current restriction on CAF may provide the auditor incentives to accept only truthful reports. In a similar vein, my analysis shows that contingent fees on unfavorable audit reports may increase auditor independence and therefore eliminate the negative externalities resulting from the provision of NAS to audit clients.

This paper contributes more broadly to the extensive literature studying auditors' incentives to provide high audit quality. DeFond and Zhang (Citation2014) provide a recent review of this vast literature. Magee and Tseng (Citation1990) analyze the pricing of audit services and the potential threats to auditor independence. Dye (Citation1993) studies the impact of an increase in auditing and accounting standards, and in auditors' legal liabilities. Laux and Newman (Citation2010) and Schwartz (Citation1997) also analyze the impact of legal liability on auditor's incentives. More recently, Gao and Zhang (Citation2019) identify the conditions under which stricter auditing standards increase audit quality, and show that stricter standards can hurt client firms more than auditors. Petrov and Stocken (Citation2022) derive the optimal choice of audit standards in the presence of auditor industry specialization. My paper investigates the joint implications of NAS and CAF on auditors' incentives and audit quality.Footnote2

Lastly, the papers most related to mine are Kornish and Levine (Citation2004) and Lu and Sapra (Citation2009), who also investigate the impact of NAS provision on audit quality. Lu and Sapra (Citation2009) find that a mandatory restriction on NAS decreases a conservative auditor's audit quality but increases an aggressive auditor's audit quality. Kornish and Levine (Citation2004) also use a contractual setting to investigate the impact of NAS on auditors. Their conclusions are related to mine: managers can influence auditors with NAS to issue favorable audit reports, whereas CAF can induce an unbiased audited accounting report. Nevertheless, they do not analyze the impact of NAS and CAF on audit effort and focus instead on their ex post effects. I study the impact of NAS and CAF on both the ex ante audit effort and on the ex post auditor independence.

2. The Model

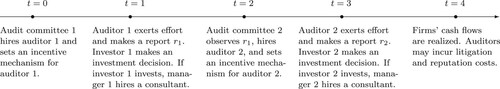

This section describes the model setup and timing. Key assumptions are discussed further in Section 2.1. The economy consists of two client firms with correlated fundamentals, indexed by , two auditors, indexed by

, and a pool of consultants that include the two auditors. There are five dates: t = 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. The timing of the model is summarized in Figure . All parties are risk-neutral and the risk-free rate is normalized to zero.

Investor i is a representative investor and owns firm i, whereas manager i runs firm i. Audit committee i hires auditor i and maximizes investor i's expected utility.Footnote3 Auditor i collects information for investor i about firm i's profitability. Based on auditor i's audit report, investor i decides whether to invest in firm i.Footnote4 Manager i is an empire builder and gets a private benefit b>0 (e.g., perks, human capital) if investor i invests in firm i. In case of investment, manager i hires a consultant to provide non-audit services (NAS) and increase the expected cash flows of firm i.

Each firm requires an initial investment I>0 and can be of two types: good (G) with probability and bad (B) with probability 1−p. A good firm yields a cash flow R>0 to investors i with probability

and a zero cash flow with probability 1−q, whereas a bad firm always yields a zero cash flow. Hiring a consultant increases by

the probability of success of a firm: a good firm with a consultant providing NAS yields a cash flow R with probability

, whereas a bad firm with a consultant providing NAS yields a cash flow R with probability τ. Further, the consultant earns a NAS rent

paid by investors. This rent admits several interpretations that I discuss in Section 2.1 (e.g., rent from imperfect competition in the NAS market). Irrespective of the provision of NAS, it is optimal for investor i to invest in firm i if and only if firm i is good, i.e.,

.

To study investment and informational externalities, the types of the two firms should be correlated. As discussed in Roychowdhury et al. (Citation2019), firms within a peer group (e.g., industry, geographic region, etc.) are affected by similar economic conditions. If peer-firm disclosures inform investors of other firms about these economic conditions, then peer-firm disclosures can help investors make more informed investment decisions. I, therefore, consider a sequential game in which, investor 1 first gets auditor 1's audit report and makes the investment decision in firm 1. Then, investor 2 observes investor 1's investment decision, gets auditor 2's audit report, and makes the investment decision in firm 2. For simplicity, I assume that the correlation between the firms' types is perfect so that the two firms are of the same type. In the online appendix, I show that my main results hold even if the correlation is not perfect.

I now describe the sequence of events in more details. At t = 0, audit committee 1 hires auditor 1 and sets an incentive mechanism to provide effort incentives to auditor 1. I describe in detail the mechanism set by the audit committee at the end of the model setup. Manager 1 does not have private information about firm 1 and sends auditor 1 a favorable report for attestation. This assumption is commonly made in the auditing literature to simplify the firm's reporting system and focuses the model on the auditing issue (e.g., Dye, Citation1993; Laux & Newman, Citation2010; Lu & Sapra, Citation2009).Footnote5

At t = 1, auditor 1 exerts an unobservable audit effort to verify the accuracy of manager 1's report.Footnote6 After exerting effort

, auditor 1 receives a signal

according to the following probabilities:

(1)

(1)

The essence of this audit technology is that more audit effort increases the probability that auditor 1 detects financial misstatements.Footnote7 If firm 1 is good, auditor 1 does not detect financial misstatements (

), because manager 1 is right to report that firm 1 is good. Otherwise, if firm 1 is bad, auditor 1 detects financial misstatements (

) with probability

and does not detect financial misstatements (

) with probability

. Auditor 1 incurs a private cost c>0 from exerting high audit effort (

), whereas the cost of exerting low audit effort (

) is normalized to 0. Manager 1 also observes auditor 1's signal

. After receiving

, and, at the end of the reporting process described in the next paragraph, auditor 1 makes public a favorable audit report (

) or an unfavorable audit report (

). Auditor 1 cannot make an unfavorable audit report (

) without evidence of financial misstatements because

is hard information.

The reporting process is summarized in Figure . According to Section 301 of SOX, audit committees play a key role in generating the financial statements and are in charge of hiring external auditors, hiring other advisors as needed, and collecting information through different sources. I therefore assume that audit committee 1 observes auditor 1's signal with probability

, and does not observe

with probability

. If

, auditor 1 has no choice but to make a favorable audit report

. Similarly, if auditor 1 detects financial misstatements,

, and audit committee 1 observes

, auditor 1 has no incentive to misreport and truthfully reports

, i.e.,

. Otherwise, if

and audit committee 1 does not observe

, a bargaining process occurs between manager 1 and auditor 1 to decide on the public audit report

. As explained below, in equilibrium, investor 1 never invests in firm 1 after an unfavorable audit report, i.e.,

. Hence, during the bargaining process, manager 1 lures auditor 1 with an NAS contract to induce a favorable audit report

.Footnote8 I rule out any ex ante agreement between manager i and auditor i before auditor i receives the audit signal,

.

At t = 1, after observing the audit report , investor 1 makes the investment decision in firm 1. Investor 1 always makes the ex post optimal investment decision given auditor 1's report. If investor 1 does not invest in firm 1, investor 1 gets a zero payoff. Otherwise, if investor 1 invests in firm 1, manager 1 hires a consultant from the pool of potential consultants that includes auditor 1, and investor 1 receives firm 1's final cash flow. Recall that, hiring a consultant increases by τ the probability of success of a firm. Further, the consultant earns a NAS rent β paid by investor 1. To focus the analysis on the incentive effects of NAS, I assume the benefit of hiring auditor 1 or another consultant to provide NAS is the same, i.e., there is no knowledge spillover. If manager 1 is indifferent between signing the NAS contract with auditor 1 or with an outside consultant, I assume manager 1 makes the preferred choice of investor 1.

At t = 2, audit committee 2 observes the audit report and investor 1's investment decision. Then, audit committee 2 hires auditor 2 and sets an incentive mechanism to provide effort incentives to auditor 2. Manager 2 does not have private information about firm 2 and sends auditor 2 a favorable report for attestation.

At t = 3, auditor 2 faces the same moral hazard problem as auditor 1 and chooses to exert audit effort . The reporting process for firm 2 is the same as for firm 1 (see Figure ). At the end of the reporting process, auditor 2 makes an audit report

. Note that if auditor 1 reports

, it is publicly known that firm 2 is bad, which implies auditor 2 reports

without exerting effort. After observing auditor 2's audit report, investor 2 decides whether to invest in firm 2. Investor 2 always makes the ex post optimal investment decision given auditor 2's report. If investor 2 invests in firm 2, manager 2 hires a consultant from the pool of potential consultants that includes auditor 2. The benefit of hiring auditor 2 or another consultant to provide NAS is the same. If manager 2 is indifferent between signing the NAS contract with auditor 2 or with an outside consultant, I assume manager 2 makes the preferred choice of investor 2.

At t = 4, firms' cash flows are realized. Auditor i bears litigation/reputation costs if auditor i makes a favorable report (

) and the cash flow of firm i is zero. Indeed, whereas an ‘error’ of an auditor is either due to a lack of effort or to a voluntary bias, it is difficult in practice for outsiders (e.g., a court) to determine ex post whether the auditor voluntarily misled investors. Thus I assume that auditors bear litigation/reputation costs for both a lack of audit effort and a voluntary bias.Footnote9

I now provide more details regarding the incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1 (resp. audit committee 2) at t = 0 (resp. t = 2). I solve for the incentive mechanism set by audit committee i that maximizes investor i's surplus. In particular, audit committee i chooses the probability of observing the signal

of auditor i and chooses the CAF and noncontingent audit fees paid to auditor i. I denote by

the noncontingent audit fees paid to auditor i, and by

the audit fees paid to auditor i contingent on an unfavorable audit report, i.e.,

. In equilibrium, I will show that audit committee i only finds optimal to pay audit fees contingent on an unfavorable audit report. Auditors and managers are protected by limited liability and their reservation utility is normalized to 0. Investors have deep pockets, and each client firm is required to hire an auditor (e.g., client firms are public). Finally, the choice of the consultant is non-contractible and is made by managers because investors often lack either the time or the knowledge to choose the consultant. Table summarizes the key notations and definitions of the model.

Table 1. Main notations and definitions.

Lastly, I make the following assumptions on the parameter values throughout the paper to rule out uninteresting corner solutions. First, high audit effort by auditor 1 is desirable for investor 1, i.e.,

(2)

(2)

Second, if auditor 1 exerts high effort, investor 2 may solely rely on an audit report

to make the investment decision in firm 2. This assumption reduces into

(3)

(3)

Third, the likelihood of good firms is sufficiently high such that investing in firm 1 is optimal for investor 1 in the absence of information, i.e.,

(4)

(4)

Fourth, the expected litigation/reputation costs are sufficiently low:

(5)

(5)

The first assumption in (Equation2

(2)

(2) ) ensures that the benefit of avoiding investment in a bad firm is sufficiently large compared to the cost of exerting high audit effort, so that auditors have a role in this model. The second assumption in (Equation3

(3)

(3) ) implies that investor 2 may decide to invest in firm 2 after a favorable audit report for firm 1. This will create a role for regulatory intervention and NAS restrictions (see Section 4). The third assumption in (Equation4

(4)

(4) ) guarantees that, as is common in theoretical auditing studies, investor 1 prefers to invest in firm 1 in the absence of an audit, but would not invest if the audit revealed a bad firm. The fourth assumption in (Equation5

(5)

(5) ) is consistent with the regulatory concern that auditors would be willing to sacrifice their independence if litigation/reputation costs were smaller than NAS rents.Footnote10 Further, this assumption also ensures that auditors do no exert high audit effort without additional incentives.Footnote11

2.1. Discussion of the Main Assumptions

Non-audit services. NAS are provided after the audit report, because, in practice, the provision of NAS is often contingent on auditors' findings. Causholli et al. (Citation2014) provide evidence that selling future NAS may impair auditor independence. Further, a major concern of regulators and practitioners is that auditor independence is at risk due to ‘lucrative consulting contracts’ (e.g., Financial Times, Citation2015). Regulators precisely consider this sequential interaction as problematic (see the discussion in the online appendix).

The NAS rent β earned by the consultants admits two interpretations:

a private benefit: human capital accumulation, perks, ego, social status, etc.;

a monetary rent: rent from imperfect competition in the NAS market (collusion between consultants, competition on quantities instead of prices, product differentiation, etc.), efficiency wage due to moral hazard, etc.

Interpretation (ii) is consistent with Lu and Sapra (Citation2009) and Simunic et al. (Citation2017), who assume that the present value of the expected monetary rents from future engagements from NAS is non-zero and exogenously given. The investors' net surplus from NAS is then , whereas, under interpretation (i), the investors' net surplus from NAS is

. I maintain interpretation (ii) in the rest of the paper but the results are similar under the two interpretations.Footnote12

Conflicts of interest. Audit committees play a key role in monitoring conflicts of interest between auditors and managers (Caskey et al., Citation2010). Nevertheless, audit committees have difficulty providing effective oversight, especially in large, complex organizations. For instance, Cohen et al. (Citation2010) show that even after SOX, some audit committees still play a passive role in helping resolve disagreements between the external auditor and management. In the same vein, Beasley et al. (Citation2009) quote a NYSE audit committee chair: ‘No one really understands how limited an audit committee is in its work. In big companies, it is virtually impossible to know what is going on without relying on management (…) and the external auditor’. Thus I assume audit committee i only observes auditor i's signal with probability

. In practice, boards may change this probability by increasing or decreasing the number of internal controls. This probability

also captures the skills and experience of the audit committee's members. More generally,

is a measure of corporate governance of firm i.

Moreover, I rule out direct monetary bribes by managers to auditors even when disguised as audit fees in excess of the competitive level, on the grounds that such openly illegal bribes would be easily detectable via ‘whistle-blowing’, and therefore punishable by law enforcers.Footnote13 Similarly, managers cannot exert pressure on auditors by committing to keep them as auditors in the future, because firing an auditor is much more costly than firing a consultant; therefore, the threat of firing an auditor in the future may not be credible (e.g., Coffee, Citation2002).Footnote14

Contingent fees.CAF are banned by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants' Code of Professional Conduct. In Section 3, I first study an unregulated economy without restriction on CAF (i.e., fees based on the outcome of the audit) and show that there is no contingent fee in equilibrium. In Section 4, in a regulated economy, I show that only audit fees contingent on unfavorable audit reports may be optimal. In practice, regulators are concerned about compensations contingent on favorable audit reports. For instance, the SEC (Citation2000) states that ‘contingent fees result in the auditor having a mutual interest with the audit client in the outcome of the work performed’. Further, as emphasized by Wagenhofer (Citation2004), the current restriction on CAF is ‘clearly a questionable exogenous restriction on feasible contracts with the auditor’.

3. Unregulated Economy

In this section, I analyze the equilibrium in an unregulated economy without restriction on the provision of NAS and on CAF. To that end, I start by solving the equilibrium reporting decision of auditors after detecting financial misstatements.

Lemma 3.1

Suppose that auditor i detects financial misstatements and audit committee i does not observe

. If

, auditor i makes a favorable audit report

and gets the NAS contract. Otherwise, if

, auditor i makes an unfavorable audit report (

) and gets the CAF,

.

If auditor i detects misstatements and audit committee i does not observe , manager i exerts pressure on auditor i to make a favorable audit report. Auditor i then balances the benefit of making a favorable audit report, in which case auditor i gets the NAS contract and bears litigation/reputation costs if firm i ultimately fails, and making an unfavorable audit report, in which case auditor i gets the CAF. As noticed by Lu and Sapra (Citation2009), what is crucial for auditors is this tension between rent and liability captured by the difference

in my model. The assumption in (Equation5

(5)

(5) ) implies that this difference is positive, and auditors are therefore ready to sacrifice their independence to get an NAS contract when CAF are small (

).

3.1. Equilibrium for Firm 1

I now solve for the incentive mechanism that maximizes investor 1's surplus. The following lemma provides the structure of the optimal incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1.

Lemma 3.2

Any optimal incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1 is composed of three variables: the probability

that audit committee 1 observes auditor 1's signal

, the audit fees

contingent on an unfavorable audit report

, and the noncontingent audit fees

. Further, if

, auditor 1 does not get the NAS contract.

A general incentive mechanism takes a simple form and can be reduced to three choice variables: the probability that audit committee 1 observes auditor 1's signal

, the audit fees

contingent on an unfavorable audit report, and the noncontingent audit fees

. Given that, in equilibrium,

, Lemmas 3.1 and 3.2 jointly imply the probability

that audit committee 1 does not observe auditor 1's signal is equal to the probability that auditor 1 gets the NAS contract after detecting misstatements. Lemma 3.2 also implies that, if auditor 1 does not collect evidence of misstatements, i.e.,

, audit committee 1 never finds it optimal to pay contingent fees and/or to have manager 1 hire auditor 1 as consultant. Intuitively, auditor 1 is only rewarded by audit committee 1 after detecting financial misstatements.

Given an incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1, investor 1's expected utility is

With probability p, firm 1 is good and auditor 1 makes a favorable audit report. Therefore, investor 1 invests in firm 1, manager 1 hires a consultant, and investor 1 gets the expected cash flow

. Similarly, with probability

, firm 1 is bad and auditor 1 makes a favorable audit report. Investor 1 then invests in firm 1, manager 1 hires a consultant, and investor 1 gets the expected cash flow

. Otherwise, with probability

, firm 1 is bad and auditor 1 makes an unfavorable audit report, which implies that investor 1 does not invest in firm 1 and pays

to auditor 1. Lastly, investor 1 pays noncontingent fees

. Similarly, auditor 1's expected utility when exerting audit effort

is

With probability p, firm 1 is good and auditor 1 incurs litigation/reputation costs ρ with probability

. Otherwise, if firm 1 is bad and auditor 1 detects misstatements, audit committee 1 does not observe

with probability

, in which case auditor 1 gets the NAS rent β and incurs litigation/reputation costs ρ with probability

. Audit committee 1 observes auditor 1's signal with probability

, in which case auditor 1 gets contingent fees

. If auditor 1 does not detect misstatements, auditor 1 incurs litigation/reputation costs ρ with probability

. Finally, auditor 1 receives noncontingent fees

and incurs the cost c when exerting high audit effort. I next solve for the incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1.

Proposition 3.1

In the unregulated economy, the incentive mechanism set by audit committee

is as follows. The noncontingent fees are

and there is no CAF,

. Moreover,

if auditor 1 does not detect financial misstatements

, auditor 1 reports

and investor 1 invests in firm 1. Manager 1 hires an outside consultant;

otherwise, if auditor 1 detects financial misstatements

, auditor 1 reports

and investor 1 invests in firm 1 with probability

in which case, manager 1 hires auditor 1 as consultant. Otherwise, with probability

, auditor 1 reports

, and investor 1 does not invest in firm 1.

The assumption in (Equation5(5)

(5) ) implies that audit committee 1 must provide effort incentives to auditor 1 above and beyond litigation/reputation costs, whereas Lemma 3.2 shows that the optimal incentive mechanism rewards auditor 1 for detecting financial misstatements. Audit committee 1 has two tools to provide effort incentives to auditor 1: the NAS contract and CAF. Proposition 1 shows that using the NAS contract is always optimal for audit committee 1. As a result, perhaps surprisingly, it is not optimal for audit committee 1 to always observe auditor 1's signal because of a lack of commitment power. Indeed, if audit committee 1 always observed auditor 1's signal, investor 1 would never invest in firm 1 when

, and auditor 1 would never get the NAS contract after detecting misstatements. Audit committee 1 therefore chooses not to observe auditor 1's signal

with probability

, in which case manager 1 exerts pressure on auditor 1 with the NAS contract. As in Lu and Sapra (Citation2009) and Kornish and Levine (Citation2004), the NAS contract is effectively contingent on the audit report, representing client pressure on auditors.

The intuition why audit committee 1 provides incentives to auditor 1 using the NAS contract instead of using CAF is as follows. In equilibrium, auditor 1's incentive constraint binds and is such that

If audit committee 1 uses contingent fees, the CAF are such that the incentive constraint binds,

, and audit committee 1 sets

. However, by using instead the NAS contract with probability

and setting

, audit committee 1 minimizes the cost of providing incentives to auditor 1:

(6)

(6)

The assumption in (Equation5

(5)

(5) ) implies that the inequality (Equation6

(6)

(6) ) is satisfied. Intuitively, the NAS rent is large relative to litigation/reputation costs so that auditor 1's expected rent,

, is large and the equilibrium probability of investing in a bad firm,

, is small. In addition, the NAS value,

, is sufficiently large. Thus, providing effort incentives with the NAS contract with probability

is cheaper than providing effort incentives with a fixed contingent fee

.

Given the optimal incentive mechanism set by audit committee

, investor 1's expected utility is

whereas auditor 1's expected utility is

Overall, auditor 1 is exactly compensated for the cost of audit effort and the expected litigation/reputation costs, and therefore gets the reservation utility 0.

The main insight of Proposition 3.1 is that audit committees may elicit audit effort using lucrative NAS contracts and let managers exert pressure on auditors. Thus having fully independent auditors may not be optimal. This is true even if investors are ex post better-off not investing in bad firms. A direct implication is that, in equilibrium, auditors only provide NAS to audit client firms with bad projects. From conversations with former auditors, this prediction seems in line with practice, because auditors are often hired to solve problems after detecting a breach in the accounts. Bankruptcy and M&A advisory services are examples of NAS often provided to distressed firms.

This positive incentive effect from NAS challenges the conventional wisdom. The traditional argument is that audit companies are reluctant to forward bad news to the company owners because they aim to please the management while hoping to receive a NAS contract. The traditional argument appears to be taken as a ‘basic truth’ when policy advice is provided (for a recent source, see CMA, Citation2019). A key assumption in my model is that firm i's manager cannot commit to hire auditor i as consultant before auditor i exerts audit effort and receives the audit signal. If auditor i and manager i could collude ex ante, NAS would lead to a negative incentive effect. Thus, to the extent that an ex ante agreement between a manager and an auditor is not enforceable, my model shows that the provision of NAS may lead to a positive incentive effect.Footnote15

3.2. Full-Fledged Sequential Equilibrium

There is no role for regulation in a setting with a single firm as audit committee 1 sets the optimal incentive mechanism and trades off the cost and benefit of using NAS to provide effort incentives to auditor 1. In this section, I solve for the full-fledged sequential equilibrium. Given the importance of peers' financial statements (see, e.g., Roychowdhury et al., Citation2019), the objective of this section is to study the negative externalities that audit committee 1 imposes on investor 2 by using NAS as an incentive tool.

Investor 2 observes auditor 1's audit report, , which is informative about the profitability of firm 2 because both firms are identical. At t = 2, given the optimal incentive mechanism

set by audit committee

, auditor 1 exerts high audit effort and investor 2 receives the signal

according to the following probabilities:

If auditor 1 makes an unfavorable audit report (

), it is publicly known that both firm 1 and firm 2 are bad. Otherwise, if auditor 1 makes a favorable audit report (

), the likelihood that firm 2 is bad is smaller than the prior probability:

(7)

(7)

Given this posterior probability, audit committee 2 sets an incentive mechanism

to maximize investor 2's expected utility:

Similarly, auditor 2's incentive constraint becomes

(8)

(8)

The following proposition describes the full-fledged sequential equilibrium in the unregulated economy.

Proposition 3.2

In the unregulated economy, the full-fledged sequential equilibrium is as follows. Audit committee 1 sets the incentive mechanism

Further, auditor 2 does not receive CAF,

. Audit committee 2 sets

and

such that

if

, auditor 2 reports

and investor 2 does not invest in firm 2. Auditor 2 does not receive noncontingent fees,

;

otherwise, if

, auditor 2 receives noncontingent fees

and,

if

, auditor 2 reports

and investor 2 invests in firm 2. Manager 2 hires an outside consultant;

if

and

, auditor 2 reports

and investor 2 invests in firm 2. Manager 2 hires an outside consultant;

otherwise, if

and

, auditor reports

and investor 2 invests in firm 2 with probability

in which case manager 2 hires auditor 2 as a consultant. Otherwise, with probability

, auditor 2 reports

and investor 2 does not invest in firm 2.

Given the incentive mechanism set by audit committee 1, if auditor 1 reports , investor 2 knows firm 2 is bad. As a result, audit committee 2 does not provide incentives to auditor 2 and investor 2 does not invest in firm 2. Auditor 2 faces no litigation/reputation cost and does not receive any fee. Otherwise, if auditor 1 reports

, investor 2 does not know whether firm 2 is good. The informativeness of auditor 1's report and the NAS rent play a key role. Indeed, from auditor 2's incentive constraint in (Equation8

(8)

(8) ), audit committee 2 does not provide effort incentives to auditor 2 if and only if auditor 1's report is sufficiently informative, i.e.,

(9)

(9)

In other words, if the posterior belief that firm 2 is bad is small relative to the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2, audit committee 2 does not provide effort incentives to auditor 2. Substituting (Equation7

(7)

(7) ) into (Equation9

(9)

(9) ), the condition in (Equation9

(9)

(9) ) is equivalent to

. Intuitively, if the cost of audit effort is small, or the expected litigation/reputation costs are large, the probability

that auditor 1 misreports is small, which increases the informativeness of auditor 1's report. Further, a smaller NAS rent makes it costlier to provide effort incentives to auditor 2.

Thus, if the audit report is sufficiently informative and the NAS rent is small, i.e.,

, audit committee 2 does not provide incentives to auditor 2 and investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1, i.e., there is herding behavior. Otherwise, if the audit report

is noisy and the NAS rent is large, i.e., if

, audit committee 2 provides effort incentives to auditor 2 using NAS. The intuition why using NAS is cheaper than CAF is the same as in Proposition 3.1. In particular, if

, manager 2 hires auditor 2 as a consultant with probability

. Investor 2 pays noncontingent audit fees to compensate auditor 2 for the expected litigation/reputation costs. Note that neither investor 1 nor investor 2 pays CAF in the full-fledged sequential equilibrium, which implies that this equilibrium is in line with practice as a restriction on CAF would not affect the equilibrium.

I now derive the investors' surplus, , in this unregulated economy and I highlight the negative externalities imposed by investor 1 to investor 2. If auditor 1's favorable audit report,

, is sufficiently informative, i.e., if

, the investors' surplus is

(10)

(10)

Investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1, i.e., there is herding behavior. Hence, investor 1's surplus is the same as investor 2's surplus except that investor 2 only pays noncontingent fees after auditor 1 reports

, and those fees are smaller (

). Indeed, as shown in equation (Equation7

(7)

(7) ), the likelihood that firm 2 is bad after

is smaller than the prior probability 1−p, and auditor 2 therefore faces smaller expected litigation/reputation costs than auditor 1.

Otherwise, if auditor 1's favorable audit report, , is noisy, i.e., if

, the investors' surplus is

(11)

(11)

The investors' surplus is similar to equation (Equation10

(10)

(10) ) but there is an additional term. Indeed, if

and

, audit committee 2 provides effort incentives to auditor 2 with the NAS contract. In particular, if the firms are bad, auditor 1 reports

with probability

, in which case investor 2 does not invest in firm 2 with probability

, and investor 2 then gets a zero payoff.

In this sequential equilibrium, the precision of auditor 1's report, , matters for audit committee 2 because audit committee 2 uses

as an input when setting the incentive mechanism for auditor 2. However, audit committee 1 sets the incentive mechanism for auditor 1 without internalizing the impact of this mechanism on investor 2. The provision of NAS by auditor 1 reduces auditor 1's independence and may lead to the following two negative externalities. First, if auditor 1's favorable audit report

is sufficiently informative, the provision of NAS may lead to inefficient herding behavior. In particular, if auditor 1 detects misstatements and manager 1 exerts pressure on auditor 1 to give a favorable report, both investor 1 and investor 2 invest in bad firms. This is an inefficient investment externality. Otherwise, if

is noisy, the provision of NAS reduces the reliability of the report

and forces investor 2 to incur the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2. This is an inefficient informational externality. Those two negative externalities create a role for regulation in this sequential game.

Before turning to the analysis of the optimal NAS restrictions in the regulated economy, I formally define auditor independence and audit quality within my setup and analyze the impact of the incentive mechanism on those two variables. I focus my attention on auditor 1 because the quality of auditor 1's report matters for investor 2. Most studies define audit quality as some variation of ‘the market-assessed joint probability that a given auditor will both detect a breach in the client's accounting system and report the breach’ (e.g., DeAngelo, Citation1981b). I apply this definition to my specific setup.

Definition

Auditor independence () is the probability that auditor 1 reports financial misstatements (

) conditional on detecting misstatements (

). Audit quality (AQ) is the unconditional probability that auditor 1 reports financial misstatements (

) if firm 1 is bad.

Interestingly, audit quality in this setup may be different from audit effort. This contrasts with a large strand of the literature that does not study ex post lack of auditor independence and, therefore, assumes the ex ante choice of audit effort is equal to audit quality. In my setup, if auditor 1 detects misstatements but manager 1 exerts pressure on auditor 1 with the NAS contract, auditor 1 makes a favorable audit report after detecting financial misstatements, whereas audit effort exerted ex ante is independent of the final audit report. Thus audit quality is the product of the ex ante audit effort and of auditor independence, i.e., .

Corollary 3.1

In the unregulated economy, auditor independence, , and audit quality,

, decrease in the audit cost, c, and in the extra probability of success of NAS, τ, and increase in the litigation/reputation costs, ρ, in the likelihood of bad firms, 1−p, and in the NAS rent, β.

Auditor independence and audit quality are moving in the same direction. First, if the cost of audit effort increases, audit committee 1 has to provide more incentives to auditor 1 to exert effort, which implies that the probability of providing NAS increases and audit quality decreases. Then, if litigation/reputation costs increase or the probability of failure of a bad firm with NAS increases (i.e., τ decreases), auditor 1 has more incentives to exert audit effort, which implies that the probability

decreases and audit quality increases. Finally, if the likelihood of bad firms increases or the NAS rent increases, audit committee 1 has to provide fewer incentives to auditor 1 to exert effort, which implies that the probability

decreases and audit quality increases.

4. Regulated Economy

As discussed previously, regulators have restricted the provision of NAS to audit clients to increase audit quality and protect investors. I model this regulatory action as follows. At t = 0, a regulator imposes a cap, , on the NAS rent that auditors can earn from audit clients. Given this NAS restriction, if investor i invests in firm i, manager i may decide to buy a quantity

of NAS from auditor i at a price

, and to buy a quantity

of NAS to an outside consultant at a price

. The value of NAS provided by auditor i becomes

, whereas the value of NAS provided by the outside consultant becomes

. Note that, if the regulator sets

, auditor i cannot provide NAS to firm i, whereas, if the regulator sets

, there is no NAS restriction as in Section 3.

I assume the regulator maximizes the total expected cash flows from the firms that accrue to investors, i.e., maximizes the investors' surplus, . This is in line with the regulatory objectives observed in practice. For instance, SOX states that ‘the PCAOB is a nonprofit corporation established by Congress to oversee the audits of public companies in order to protect investors (…)’. This objective function of the regulator is also consistent with the auditing literature (e.g., Petrov & Stocken, Citation2022; Radhakrishnan, Citation1999). I also derive the socially optimal regulation at the end of this section.

In this regulated economy, the impact of an NAS restriction on audit quality is ambiguous. On the one hand, audit quality is negatively affected by the provision of NAS, because manager 1 can exert pressure on auditor 1 with an NAS contract, and auditor 1 may make a favorable audit report after detecting financial misstatements. Therefore, NAS restrictions may eliminate this possibility and may increase auditor independence. On the other hand, NAS restrictions may decrease ex ante audit effort because the incentive effect of the NAS contract may disappear. As a result, the overall impact of NAS restrictions on audit quality, which is the product of audit effort and auditor independence, is unclear and depends on the possibility for investors to use CAF.

4.1. Contingent Audit Fees Disallowed

I first analyze the equilibrium in the regulated economy without CAF, i.e., . The only forces that remain for audit committees to provide effort incentives to auditors are the market-based reputation/litigation costs, ρ, and the NAS rent,

, that auditors can earn from audit clients. The following lemma shows the impact of NAS restrictions on audit quality.

Lemma 4.1

In the regulated economy, if CAF are disallowed,

if

, auditor 1 is fully independent,

, and audit quality is

;

otherwise, if

, auditor independence is

and audit quality is

.

If the NAS restriction is tight, i.e., , audit committee 1 cannot provide sufficient incentives to auditor 1 to exert high audit effort. Auditor 1 is then fully independent but auditor 1 exerts low audit effort. Hence, audit quality is equal to

. Otherwise, if the NAS restriction is loose, i.e.,

, audit committee 1 provides incentives to auditor 1 using NAS, and both auditor independence and audit quality increase with the NAS restriction,

, as in Corollary 3.1. Thus the regulator does not restrict the provision of NAS to audit clients in the regulated economy without CAF.

Proposition 4.1

In the regulated economy, if CAF are disallowed, the regulator does not restrict NAS, i.e., .

As discussed in the introduction, recent regulatory actions have been taken in the USA and the EU to ban a number of NAS that auditors can provide, and to cap the NAS fees that auditors can receive from audit clients. My analysis underlines that those regulatory actions might be inefficient. Indeed, in a regulated economy without CAF, increasing auditor independence may even decrease audit quality. The main reason is that regulators focus on only one piece of the puzzle: the ex post decrease in auditor independence. However, I demonstrate that both the ex post independence problem and the ex ante incentive effect should be considered.

Given an NAS restriction, , the expressions of the investors' surplus,

are similar to the ones given in (Equation10

(10)

(10) ) and (Equation11

(11)

(11) ). The only difference is that auditors earn an NAS rent

in the regulated economy instead of β in the unregulated economy. The following corollary provides some comparative statics on the investors' surplus.

Corollary 4.1

In the regulated economy, if CAF are disallowed and , the investors' surplus,

, decreases in the audit cost, c, and in the NAS rent, β, and increases in the NAS restriction,

.

First, if the cost of audit effort increases, audit committees have to provide more incentives to auditors to exert effort, which implies that the investors' surplus decreases. Second, if the NAS rent increases, investors pay a higher rent to the consultants and the investors' surplus decreases. Lastly, the investors' surplus increases with the NAS restriction, , as auditors' incentives to exert effort increase with the NAS restriction.

The main insight is that auditor independence, audit quality, and investors' surplus are not necessarily moving in the same direction. In particular, an increase in auditor independence may lead to a decrease in audit quality and a decrease in investors' surplus. As a result, the PCAOB's objective ‘to protect investors (…) by promoting (…) independent audit reports’ might be inconsistent. Using the parameter values provided in Footnote 11, Figure illustrates the relationship between auditor independence, audit quality, and investors' surplus when there is herding behavior, i.e., when . Next, I study the equilibrium in the regulated economy with CAF.

4.2. Contingent Audit Fees Allowed

From a regulatory point of view, it may be optimal to allow CAF for unfavorable audit reports and to restrict the provision of NAS by auditors. Removing the current restriction on CAF for unfavorable reports would increase auditor independence while preserving the ex ante incentives to exert audit effort. The regulator may want to increase the overall quality of audit reports because of the negative externalities resulting from a lower audit quality.Footnote16 The following lemma studies this tradeoff.

Lemma 4.2

There exists a cutoff , such that, in the regulated economy, if CAF are allowed,

if

, auditor 1 is fully independent,

, and audit quality is

;

otherwise, if

, auditor independence is

and audit quality is

.

If the NAS restriction is tight, i.e., , audit committee 1 finds it optimal to provide incentives to auditor 1 using CAF. Auditor 1 is then fully independent and audit quality is equal to audit effort, i.e.,

. Otherwise, if the NAS restriction is loose, i.e.,

, audit committee 1 provides incentives to auditor 1 using NAS. Auditor independence and audit quality then increase with

as in Corollary 3.1.

Given this impact of a NAS restriction on audit quality, the regulator trades off two effects when deciding to restrict the provision of NAS to audit clients. On the one hand, a tight NAS restriction maximizes audit quality and therefore reduces the investment and informational externalities resulting from the provision of NAS to audit clients. On the other hand, a tight NAS restriction also increases the investors' cost of providing incentives to auditors. The following proposition highlights this tradeoff.

Proposition 4.2

In the regulated economy, if CAF are allowed, there exists a cutoff such that,

if

, the regulator chooses any NAS restriction

;

otherwise, if

, the regulator does not restrict NAS, i.e.,

.

The cutoff x is defined in the proof of Proposition 4.2.

Proposition 4.2 highlights how an NAS restriction combined with the possibility of using CAF can eliminate the two negative externalities resulting from the provision of NAS by auditor 1. It is instructive to consider separately the two cases of Proposition 3.2 to provide some intuitions for Proposition 4.2. First, if auditor 1's favorable audit report, , is sufficiently informative, i.e.,

, investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1 without providing effort incentives to auditor 2. In this case, the cutoff x is equal to 1, and the regulator restricts NAS if and only if

(12)

(12)

Intuitively, the left-hand side of (Equation12

(12)

(12) ) captures the negative externality from herding, whereas the right-hand side of (Equation12

(12)

(12) ) relates to the expected NAS rent earned by auditor 1. If the condition in (Equation12

(12)

(12) ) is satisfied, the regulator restricts the provision of NAS to audit clients to maximize audit quality. In particular, if the NAS rent earned by auditor 1 is small relative to the cost of investing in a bad firm, the probability that auditor 1 misreports is relatively large, which increases the likelihood that investor 2 invests in a bad firm. The NAS restriction would then eliminate the negative investment externality.

I now consider the alternative case in which auditor 1's favorable audit report is sufficiently noisy, i.e., . Investor 2 does not rely on auditor 1's audit report and incurs the cost of providing effort incentives to auditor 2. In this case, the cutoff x is strictly smaller than one, and the regulator restricts NAS if and only if

(13)

(13)

The right-hand side of (Equation13

(13)

(13) ) relates to the NAS rent earned by auditor 1. Further, the parameter x increases with the probability

, which implies that the left-hand side of (Equation13

(13)

(13) ) captures the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2. If the condition in (Equation13

(13)

(13) ) is satisfied, the regulator restricts the provision of NAS to audit clients to maximize audit quality and investor 2 no longer incurs the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2. In particular, if the NAS rent earned by auditor 1 is small relative to the cost of providing incentives to auditor 2, the probability that auditor 1 misreports is large, which makes auditor 1's report even less informative. The NAS restriction would then eliminate the negative informational externality.

When the regulator optimally restricts the provision of NAS, i.e., when , audit quality is maximal, i.e.,

and investor 2 makes the same investment decision as investor 1. The investors' surplus becomes

Next, I derive some comparative statics on the investors' surplus.

Corollary 4.2

In the regulated economy, if CAF are allowed and , the investors' surplus,

, decreases in the cost of audit effort, c, in the litigation/reputation costs, ρ, in the NAS rent, β, and increases with the extra probability of NAS, τ.

First, if the cost of audit effort increases, audit committee 1 has to provide more incentives to auditor 1 to exert effort, which implies that the investors' surplus decreases. Second, if litigation/reputation costs increase, investors have to pay larger noncontingent audit fees to compensate auditors for the increase in the expected risks, and the investors' surplus then decreases. Third, if the NAS rent increases, the net surplus from NAS, , decreases, which implies that the investors' surplus decreases. Lastly, if the extra probability of the NAS contract increases, the probability of success of the firm increases and the investors' surplus also increases.

Using the same numerical example as in Figure , Figure illustrates the relationship between auditor independence, audit quality and investors' surplus when there is herding behavior and restricting NAS is optimal, i.e., and

.

The main takeaway of this analysis is that, if the negative externalities of NAS dominate the positive incentive effect, then maximizing audit quality increases investors' surplus and allowing audit fees contingent on unfavorable audit reports is optimal. Indeed, investors can recover truth-telling if the provision of NAS by the auditor is banned and CAF for unfavorable audit reports are allowed. As in Kornish and Levine (Citation2004), removing the current restrictions on CAF would eliminate these negative informational externalities and increase audit quality. This result contrasts with Beeler and Hunton (Citation2002) and Dye et al. (Citation1990), who find that contingent fees may induce auditors to bias reports.

Finally, I derive the optimal regulation that maximizes social welfare, defined as the sum of the expected utilities of all the players.

Proposition 4.3

Social welfare is maximal when CAF are disallowed and auditors cannot provide NAS.

Proposition 4.3 shows that there is a conflict between maximizing investors' surplus and maximizing social welfare. Intuitively, investing in a bad firm is costly for investors given that they have to pay NAS rents to consultants (). On the contrary, managers derive private benefits when investors invest in bad firms, and NAS rents are just monetary transfers from investors to consultants, which makes investment in bad firms less costly from a social welfare perspective. Overall, even though regulators may also internalize the welfare of auditors and managers, the main insights of the paper are still relevant for regulators as long as the weight that they put on investors' surplus is sufficiently large.

5. Regulatory Implications and Empirical Predictions

In this section, I discuss some regulatory implications and empirical predictions of my analysis. First, the regulatory debate is mostly focused on the impact of the provision of NAS by auditors to audit clients on auditor independence and audit quality. However, my analysis suggests investors may optimally let managers exert pressure on auditors with NAS contracts because doing so ultimately leads to a higher audit quality. Indeed, the possibility of providing NAS contingent on detecting financial misstatements may increase audit effort. In the absence of CAF, increasing auditor independence may decrease ex ante audit quality. As a result, the PCAOB's objective ‘to protect investors (…) by promoting (…) independent audit reports’ might be inconsistent.

Nevertheless, regulators may want to restrict the provision of NAS by auditors and allow CAF to maximize audit quality because of negative externalities. I highlight the externalities resulting from this decrease in audit quality when investors rely on peer-firms' financial statements to make investment decisions. In particular, the decrease in the reliability of the financial statements due to the provision of NAS to audit clients may lead to inefficient investment and informational externalities. As a result, allowing audit fees contingent on unfavorable audit reports might be optimal because doing so would increase overall audit quality while preserving the ex ante incentives to exert audit effort. Kornish and Levine (Citation2004) also discuss the optimality of CAF to increase auditor independence.Footnote17

The variant of the model without CAF generates several empirical predictions. First, my analysis predicts that audit effort is larger when the auditor can provide NAS to audit clients. This prediction is consistent with the empirical findings of Davis et al. (Citation1993), who measure audit effort using audit-hours and find additional effort for audits of clients who also purchase NAS. More importantly, the model predicts that a ban on the provision of NAS to audit clients would increase auditor independence but decrease audit quality. This result is important given that many empirical studies use proxies of audit quality to assess auditor independence. My analysis suggests that the relation between those two key variables may be more complex. A direct consequence is that a positive relationship between NAS fees and financial misstatements does not imply that NAS negatively affect audit effort and audit quality. On the contrary, I show that a positive relationship may indicate that incentives are provided to auditors using NAS and that this mechanism improves audit effort and ex ante audit quality.

Further, my analysis predicts that auditors provide NAS to audit clients after detecting financial misstatements in nonprofitable firms. The empirical implication is straightforward: the larger the level of non-audit fees, the lower the financial health of the client firm. This prediction may explain the negative reaction of investors of a client firm after having learned that the external auditor also provides NAS to the client firm. Indeed, as discussed in the introduction, studies using perception-based proxies find that investors penalize companies purchasing NAS. For example, NAS is associated with more negative abnormal returns, a larger cost of capital, and a lower likelihood of auditor ratification (DeFond & Zhang, Citation2014). Those results are in line with the predictions of my model.

Lastly, an important cross-sectional prediction of Corollary 3.1 is that audit quality increases with the likelihood of nonprofitable firms. Indeed, the incentive mechanisms set by audit committees reward auditors for detecting financial misstatements in bad firms. Hence, in industries with larger probabilities of project failure, auditors may have higher incentives to exert audit effort and audit quality may be higher.

6. Conclusion

This paper provides a model that delivers new insights into the consequences of the provision of NAS by audit firms to audit clients and investigates the joint implications of NAS and CAF on auditors' incentives and audit quality. In the model, litigation and reputation costs do not provide sufficient incentives to auditors to exert audit effort. Investors of client firms may therefore let auditors provide NAS because of an incentive effect. Indeed, the possibility of providing NAS contingent on detecting financial misstatements increases auditors' incentives to exert audit effort. However, the provision of NAS also reduces auditor independence, which may decrease audit quality and in turn render the provision of NAS by auditors undesirable. Thus my analysis uncovers an interesting tradeoff for regulators between the positive incentive effect and the decrease in auditor independence. Removing the current restriction on CAF may offset the ex post decrease in audit quality while preserving the ex ante incentives.

I believe that this framework could be extended in several directions and there are many interesting routes for future research. For instance, I do not model competition in the audit market to keep the model simple and to focus the analysis on the incentive effects of NAS. It would be interesting to consider an endogenous audit competition setup to investigate the interaction between audit competition, provision of non-audit services and incentives for auditors to exert audit effort. For example, other things being equal, a fiercer competition in the audit market could make the NAS rent more important for auditors and could exacerbate the NAS incentive effect.

Finally, my model admits broader interpretations and many other applications of this idea come to mind. This tradeoff between ex ante incentives and ex post decrease in auditor independence could be applied to other situations such as the revolving doors in the accounting industry. It has often been argued that letting auditors work for their audit clients could create potential conflicts of interest. Auditors would be willing to let a client hide losses hoping that their favor would be rewarded later in their careers by being hired by the client. For instance, Section 206 of SOX was enacted to increase the independence of accounting firms whose ex-auditors obtained a senior financial reporting position with their current audit clients. However, hiring a former auditor, like hiring a consultant, may increase a firm's value because of the former auditor's valuable experience. Therefore, investors of client firms may optimally let managers hire former auditors because this could provide ex ante incentives to auditors.

Supplemental Data and Research Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2022.2066011.

Section A. Institutional setting

Section B. Robustness checks

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of my dissertation at the Université Toulouse 1 Capitole. I am grateful to my advisor, Guillaume Plantin, who has provided invaluable advice and constant support at every stage of this work. I have also greatly benefited from the comments of Robert Goex (the editor), two anonymous referees, Andrea Attar, John Barrios, Jeremy Bertomeu, Bruno Biais, Milo Bianchi, Judson Caskey, Hans Christensen, Jacques Crémer, Ronald Dye, Ralf Ewert, Henry Friedman, Pingyang Gao, Jonathan Glover, Ulrich Hege, Thomas Hemmer, Clive Lennox, Robin Litjens, Thomas Mariotti, Michael Minnis, Florin Sabac, Bernard Salanié, Haresh Sapra, Reed Smith (discussant), Lars Stole, Alfred Wagenhofer, Ira Yeung (discussant), and the workshop/conference participants at the Chicago Booth School of Business, Tilburg University, Toulouse School of Economics, the University of Graz, the University of Zurich, the 2017 AAA Auditing Section Midyear Meeting, the 2017 CAAA Annual Conference, and the 2017 EAA Annual Congress. Errors remain mine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the UK, the Financial Reporting Council told the biggest audit firms to separate their audit and consulting businesses by 2024 (FRC, Citation2020). On the contrary, in the USA, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed loosening some of the restrictions around whether an auditor's objectivity and impartiality are compromised because it has non-audit ties to a client (SEC, Citation2019). In the online appendix, I provide additional information regarding the institutional setting, and I explain why the provision of NAS by audit firms to audit clients remains a key concern for regulators.

2 This paper is also related to the extensive literature that has been devoted to the analysis of collusion in a principal-supervisor-agent setting following the seminal work of Tirole (Citation1986). For example, Che (Citation1995) studies the optimality of allowing collusion for incentives reasons in a different setup. Baiman et al. (Citation1991) study the ex ante collusion between a manager and an auditor, and characterize the resulting optimal owner–manager contract. In the same vein, Friedman (Citation2014) studies a CEO pressuring a CFO to bias financial reports. In this paper, ex post collusion between managers and auditors is part of the optimal mechanism for investors to elicit audit effort.

3 Given that audit committee i maximizes investor i's expected utility, I use ‘audit committee i’ and ‘investor i’ interchangeably in the rest of the paper.

4 As in Gao and Zhang (Citation2019), Liao and Radhakrishnan (Citation2016), or Radhakrishnan (Citation1999), I assume that the current investor i makes the investment decision. I could alternatively distinguish between current and new investors of firm i. The current investor sells firm i in a competitive market to new investors who in turn make the investment decision. Such a setting introduces additional notations without affecting the results.

5 For the interactions between financial reporting and auditing, see, e.g., Caskey et al. (Citation2010), Deng et al. (Citation2012), or Mittendorf (Citation2010).

6 For simplicity, I assume that audit effort is binary. However, in the online appendix, I show that the structure of the optimal incentive mechanism is similar if audit effort is continuous.

7 This audit technology assumes away false positives, i.e., when the auditor discovers misstatements in case of a good firm. This is innocuous and reflects that Type I errors are rare and unimportant in audit practice. See, among others, Ewert (Citation1999), Newman et al. (Citation2005), and Simunic et al. (Citation2017) for a similar assumption.

8 The managers' private benefit in case of investment is sufficiently high so that the agency conflict cannot be eliminated through compensation contracts. As discussed by Baldenius (Citation2003), The Economist lists empire building benefits as the main example for agency problems in its online ‘Economics A–Z’. Hennessy and Levy (Citation2002) find strong empirical evidence for empire building benefits to affect investment decisions. Further, as in Acemoglu and Gietzmann (Citation1998), this assumption is not crucial, and other conflicts of interest between managers and investors would work as well.

9 In the online appendix, I show that the following alternative assumption would not affect the results: auditor i bears litigation/reputation costs if auditor i makes a favorable report (

), firm i is bad, and the cash flow of firm i is zero. Intuitively, if firm i is good, the litigation/reputation costs do not affect auditor i's choice of effort, because auditor i never detects financial misstatements.