?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We examine whether tax audits become more efficient if tax auditors have access to information about statutory audit adjustments. To this end, we extend the standard tax compliance game by including a statutory auditor and analyze the strategic interactions among a firm issuing financial and tax reports, a statutory auditor, and a tax auditor. We show that granting the tax auditor access to information on statutory audit adjustments can, in some cases, increase tax revenues while simultaneously decreasing tax audit frequency. Thus, more information sharing between statutory and tax auditors could be a policy instrument to combat tax evasion and increase tax audit efficiency. However, the tax audit efficiency enhancing effect comes at the cost of a reduction in financial statement quality as the probability of overstated financial assets increases. Moreover, depending on the importance of firms' financial statement valuation, the additional information may also reduce tax revenues. The regulator must, therefore, carefully weigh the potential efficiency gains from information sharing on statutory audit adjustments that are derived in this study against the potential efficiency losses.

1. Introduction

In many countries, tax administration budgets have declined significantly in recent years, and tax administrations have therefore reduced their workforces. For example, the United States Internal Revenue Service reduced its number of employees from 94,711 in 2010 to 74,397 in 2020 (IRS, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Similarly, the number of employees at the United Kingdom tax authority, the HMRC, fell from 91,167 in 2005 to 61,370 in 2014 (Slemrod, Citation2016). This raises the importance of improving the tax audit selection process to increase tax revenues per tax audit costs, i.e., tax audit efficiency.

One idea to improve the tax audit selection process is based on the observation that financial statements are often subject to two kinds of audit: a statutory audit that is conducted by an independent statutory auditor and, usually with a time lag, a tax audit that is conducted by the country's tax administration. Because financial accounting values are generally positively correlated with tax accounting values, informing the tax auditor of adjustments made during the statutory audit could help reduce the cost of the tax audit by decreasing the tax audit probability of items that have already been adjusted downward by the statutory auditor.

The potential for a division of labor between statutory auditing and tax auditing was addressed early on in practice due to the similarity of the activities (e.g., Wenzig, Citation1983). Moreover, the rules in several countries suggest that countries seem to believe in the potential benefits of information exchange between statutory and tax auditors because they require taxpayers to file the statutory audit report together with the tax return (e.g., in Belgium, Germany, and the United Kingdom; see Table in the Appendix). However, we are not aware of any theoretical study that examines whether information sharing between statutory and tax auditors could actually result in a lower frequency of tax audits without a loss of tax revenue. Against this background, this paper uses a game-theoretic model to investigate how granting tax auditors access to information about statutory audit adjustments affects the efficiency of the tax audit regime.

In our model, there are three strategic players as follows: (i) a manager with incentives to bias tax reports downwardsFootnote1 and to bias financial reports upwards; (ii) a statutory auditor with incentives to detect upward-biased financial reports; and (iii) a tax auditor with incentives to detect downward-biased tax reports. The true book and tax values are positively correlated to recognize that there is usually some book-tax conformity. Both auditors can perfectly verify the respective true value. However, audits are costly. The manager benefits from high accepted financial reports and low accepted tax reports. In the event of detected misreporting, the manager suffers disutility (e.g., from reputation losses, penalties, and interest payments). In this setting, we compare two information regimes, namely, one in which the tax auditor has access to information on statutory audit adjustments and one in which it does not have access to this information.

In both information regimes, we determine the mixed-strategy equilibria, where the two auditors employ a probabilistic audit strategy and certain taxpayers randomize their reporting behavior.Footnote2 In these equilibria, we compare the effects of the two information regimes on tax revenues and tax audit frequency.

Our main finding is that the tax auditor's access to information on statutory audit adjustments can indeed lead not only to a lower frequency of tax audits but also, in some cases, to higher tax revenues. However, a lower tax audit frequency always comes at a cost. Either tax revenues are reduced or financial accounting income is increasingly overstated. Which of these cases occurs depends on how much weight the manager assigns to book versus tax income. In addition, we show that providing access to statutory audit adjustments does not affect tax audit efficiency when the manager places a higher weight on book income than on tax income.

The intuition behind the ambiguous effect of additional information is as follows. For taxpayers, there is always a tradeoff between the benefit of tax savings and potential non-tax costs when deciding about legal tax planning or tax evasion. The non-tax costs include sacrificing a high book income to increase the probability of obtaining tax savings. With the increasing importance of financial statements, these non-tax costs rise, and tax planning becomes less worthwhile. Tax auditors anticipate this behavior and set their audit probabilities such that, in equilibrium, taxpayers are indifferent between correct and incorrect tax reporting. When tax auditors have access to the statutory audit adjustments, they can reduce their audit probability for the reports that are already adjusted downward by the statutory auditor because taxpayers who simultaneously conduct upward book management and downward tax management already face a high risk that the statutory auditor will detect misreporting. Thus, in this case, the non-tax costs are high, and a lower tax audit probability is sufficient to make the taxpayer indifferent between correct and incorrect tax reporting.

In the case of a low importance of financial statement valuation, some taxpayers simultaneously manage earnings upwards and report a false tax income. When upward management is detected and tax auditors receive this information, they can reduce their audit probability as argued above. However, in equilibrium, all taxpayers determine their reporting probabilities such that the tax auditor is indifferent between auditing and not auditing a report. Because the benefits and costs of the auditor do not depend on whether there is access to statutory adjustments, this implies that the average probability of incorrect tax reporting is not affected; thus, the lower tax audit frequency is accompanied by lower tax revenues. Accordingly, the tax revenue and tax audit frequency decrease such that the overall effect on tax audit efficiency is ambiguous.

In the case of a medium importance of financial statement valuation, the non-tax costs of incorrect tax reporting rise such that earnings management always entails truthful tax reporting because a truthful tax report reduces the risk that the statutory auditor corrects earnings management. Therefore, reports with and without adjusted book income become very informative to the tax auditor. As a consequence, the tax auditor can reduce the audit probability for reports in which the statutory auditor has detected upward management to zero without losing tax revenues. Thus, tax revenues increase and tax audit frequency decreases, so tax audit efficiency increases. However, this efficiency-enhancing result has the drawback that it reduces the quality of financial statements. Because taxpayers increasingly sacrifice tax savings to increase the probability of obtaining a high financial statement valuation, the probability of upward-biased financial statements increases.

Finally, in the case of a high importance of financial statement valuation, the additional information on statutory audit adjustments is no longer informative. Due to taxpayers' high non-tax costs, the tax auditor reduces the audit probability for all reports without book-tax differences to zero, and this is already the case if the tax auditor does not have the additional information.

Our study makes several contributions. First, we contribute to the tax compliance research stream that recognizes that the detection probability is the result of a game between taxpayers and the government and is thus endogenous (Bayer, Citation2006; Beck et al., Citation1996, Citation2000; Beck & Jung, Citation1989; De Simone et al., Citation2013; Erard & Feinstein, Citation1994; Graetz et al., Citation1986; Reinganum & Wilde, Citation1986, Citation1988; Rhoades, Citation1999; Sansing, Citation1993). The two studies most related to our paper are Mills and Sansing (Citation2000) and Mills et al. (Citation2010). In Mills and Sansing (Citation2000), the tax auditor observes the (correct) financial statement valuation, which results in a higher audit probability for positive book–tax differences. Mills et al. (Citation2010) investigate the effects of truthfully disclosed uncertain tax positions according to FIN 48. We contribute to this research by significantly extending prior models. On the one hand, we add a strategic statutory auditor to the game and allow taxpayers to misreport both financial and tax reporting positions. On the other hand, we also examine how the interaction between strategic statutory and tax auditors in the form of an information exchange on statutory audit adjustments affects tax audit efficiency.

Second, our model can provide implications for specific joint audit arrangements. Joint audits are an issue in several recent regulatory reform discussions. Several papers discuss the impact of joint audits on audit quality or audit fees.Footnote3 Our model carries over to a joint audit setting, where two auditors sequentially consider different but related audit fields (with individual liability) and aggregate their findings into a single report. Therefore, our model predicts how different information regimes between these two auditors influence financial statement quality.

Third, our model also adds to the debate among researchers and politicians (e.g., Hanlon et al., Citation2008; Niggemann, Citation2020; Tang, Citation2015) about how book–tax conformity may affect tax compliance and the true and fair view of financial statements. Due to the correlation between financial and tax accounting, the statutory and the tax audit are also strategically interrelated, and changes in tax audit policy may thus also affect financial statements. In particular, providing the tax auditor with information on statutory audit adjustments may improve the efficiency of the tax audit but may also harm the true and fair view of the financial statements. These opposing consequences can result in a conflict between regulators who oversee statutory audits and tax audits. Thus, our findings extend the prior discussion by showing that the controversy about the tradeoff between lower tax avoidance and informativeness of financial statements carries over to the regulation of tax and statutory audits.

With respect to policy implications, the strategic interaction among statutory auditors, tax auditors, and taxpayers reveals that information sharing between statutory and tax auditors has the potential to increase tax audit efficiency. In a period of decreasing resources for many tax administrations (Nessa et al., Citation2020), this is an important policy result. However, our model also shows that firms and auditors respond to the changing information environment and that the desired positive effects always comes at a cost. Thus, policy makers have to carefully weigh the benefits and drawbacks of changing the information environment of tax auditors.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the second section, we present the model. In the third section, we present the equilibrium and efficiency results. We discuss the results and derive implications for future research in the fourth section. The fifth section concludes the paper.

2. The Model

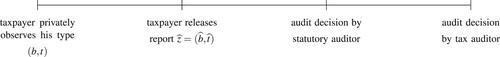

We consider a multistage game that involves three players, specifically, the manager of a firm, a statutory auditor, and a tax auditor. The manager has to release a report about both the tax and the financial statement valuation of an issue.Footnote4 Subsequently, first the statutory auditor determines her audit decision, and then, the tax auditor has to decide whether to audit the tax report. All players are assumed to be risk-neutral.

In the first stage of the game, the firm's manager (in the following denoted as the ‘taxpayer’) faces an asset valuation issue. The asset's correct book value in the financial statements is . The value 0 captures a low valuation, and the value 1 captures a high valuation of the asset. A similar valuation issue – with a potentially different outcome – arises for tax purposes, where the proper valuation is

. Consider different depreciation, amortization or impairment rules, different rules concerning the capitalization of assets or the fair value vs. historical costs valuation as examples of possibly different book and tax valuations. For both financial statement and tax issues, a low (high) valuation also implies a low (high) income. Therefore, we use the terms book (tax) valuation and book (tax) income interchangeably.

We refer to the true valuations as the taxpayer's type z. At the beginning of the game, nature chooses a type

for the taxpayer. Nature's move is observed only by the taxpayer such that the correct valuations are his private information.Footnote5 A report of a taxpayer of type

communicates a type

to the statutory auditor. The tax auditor observes only the reported tax valuation

in

. Potential additional information for the tax auditor is provided by the statutory auditor and differs across both information regimes that we consider in the paper.

We assume the following common prior probability distribution over the taxpayer's type:

The ex ante probabilities

and

are 0.5.Footnote6

The conditional probabilities

are given by

and

. We assume that 0.5<p<1.

Given the two assumptions above, the joint probabilities are

,

,

and

. Furthermore,

.

Parameter p is a measure of the conformity between the tax and financial statement valuations. A strong conformity means , and a low conformity implies

. In this sense, the assumption that p>0.5 ensures that the correlation between the tax and financial statement valuations is positive.

At the beginning of the game, after observing his type, the taxpayer decides the valuations to be reported to the statutory auditor. We assume that the taxpayer makes simultaneous reports of book and tax income, whereas in practice, there is usually a time gap between the filing of annual statements and tax returns. Our simplifying assumption of simultaneous reports is based on the fact that taxpayers have to calculate the tax liability when preparing the annual accounts because otherwise, they will not be able to report the correct amount of deferred taxes. The taxpayer may bias the reported valuation, for example, because he is interested in a low asset value for tax assessment; we specify the taxpayer's objective function after we have introduced the other players of the game.

In the second stage of the game, the statutory auditor conducts the annual financial statement audit after having observed the taxpayer's reported valuations . The statutory auditor determines whether to audit

or not

the reported financial statement valuation. The costs of the statutory audit are given by

and

. For the sake of simplicity, we assume a perfect audit technology for the statutory auditor regarding the financial statement valuation. That means that for

, the statutory auditor detects with certainty an inaccurate financial statement valuation by the taxpayer. For

, the statutory auditor will not detect any misreporting.

In line with the literature,Footnote7 we assume that the statutory auditor's main concern is to reduce litigation risk. Litigation implies direct costs such as payments for damages or settlements and indirect costs from a loss of reputation. It is well documented that litigation risk comes from upward earnings management. Heninger (Citation2001), for example, finds that the risk of auditor litigation is positively related to income-increasing discretionary accruals. Incentives for income increasing earnings management originate not only from financial reporting but also from financial or incentive contracts.Footnote8 As a consequence, auditors are conservative in that they tolerate income-decreasing and scrutinize income-increasing accounting policies.

We consider auditor conservatism as follows. The auditor benefits from detecting an overstatement of the asset value but does not benefit from detecting income-decreasing accounting choices.Footnote9 The benefit from detecting an overstatement is given by

. Thus, the preferences of the statutory auditor can be characterized by

where

is the final financial statement valuation after the statutory auditor's decision

, with

and

.

We need to assume that to ensure that auditing can be induced as equilibrium behavior. The statutory auditor's audit decision

is not observable to the tax auditor, who enters the game at its final stage.

The tax auditor also possesses a perfect audit technology regarding the reported tax valuation and has to decide whether to audit

the tax valuation

or not

. The tax auditor benefits from detecting an understated tax valuation (

although t = 1) but earns no benefit from detecting an overstatement.Footnote10 Denoting the tax auditor's benefit for detecting an understatement by

and the personal cost of auditing actions

by

, the tax auditor's objective function can be written as

(1)

(1)

Here,

denotes the final tax valuation after the tax auditor's decision

, with

,

. We further assume that

and

. Similar to the case of the statutory auditor, we impose the regularity condition

.

In our model, each auditor's motivation to conduct an audit is determined by her cost ratio denoted by for the statutory auditor and

for the tax auditor. The cost ratios are defined as follows:

and

. These cost ratios are measures of the tax and statutory auditors' incentives. When the cost ratios

are lower, the incentives of the statutory and tax auditors are higher-powered. In this paper, we assume medium incentives for tax auditors that are characterized by the values of the incentive parameter

such that

.Footnote11 The exact parameter values are provided in online Appendix 2.

We are now able to specify the taxpayer's objective function. Assuming that the taxpayer is interested in a low asset value for tax assessment and in a high asset value in the financial statements, a taxpayer of type maximizes the following function:

(2)

(2)

where

represents penalties and interest payments due upon a detected failure in the tax valuation.

includes all negative consequences for the preparer of deficient financial statements. These can be increased layoff risk or adverse (reputational) effects on the external or internal labor market, for example. We define

(3)

(3)

The parameters

and

are positive weights that indicate the taxpayer's preferences for financial statement and tax valuation. Depending on the relation between

and

we distinguish the following three settings within our analysis: (1) low importance of financial statement valuation (

); (2) medium importance of financial statement valuation (

); and (3) high importance of financial statement valuation (

). The three settings capture different degrees of incentives for income-increasing accruals in the financial statements that may be induced by managerial incentives, capital market exposure, or the ownership structure. Examples of firms with presumably low importance of financial statements are unlisted companies with little need for external financing, listed firms with low capital market pressure, and firms without performance-based incentive systems that depend on pre-tax earnings. By contrast, firms that place a high weight on financial statements are primarily listed firms with very high capital market pressure. These firms will conduct upward book income management even if this leads to higher tax payments (Erickson et al., Citation2004) but never conduct conforming tax avoidance, i.e., downward management of both book and tax income. Finally, firms with medium importance of financial statements include private firms that use external funding or that use performance-based incentive systems and public firms with moderate capital market pressure. Given the prevalence of private firms worldwide and the fact that private firms often rely on external debt financing,Footnote12 we expect that the case of medium importance of financial statements is the most common. The three settings can also differ with respect to the statutory auditor's litigation risk. However, we abstain from capturing this interaction between

and

because we hold the importance of financial statements constant when we compare the implications of different information regimes in the following.

We assume that all objective functions and preference parameters are common knowledge in the game. This also implies that both auditors know the weights and

for certain (they are public information). Although it seems to be more realistic to model the weights as the taxpayer's private information, we use this simplifying assumption to reduce complexity. If the auditors only know a probability distribution over the taxpayer's weights instead of their true values, then taxpayer's type space will be enlarged to such an extent that the model will no longer be tractable.Footnote13

Analyzing the effect of different information environments on tax compliance, we consider two different regimes. Across the regimes, we vary the information available to the tax auditor when she has to select an audit strategy; see Table . We denote the information (set) available to the tax auditor at the time of her audit decision by i.

Table 1. Different informational structures considered in the game

In both regimes, the statutory auditor observes the taxpayer's report . The tax auditor observes the reported tax valuation

and the final financial statement valuation

after the statutory auditor's auditing choice,

, in the first regime, whereas in the second regime, the tax auditor can also observe whether the statutory auditor has corrected the taxpayer's financial statement valuation:

, with

, where C indicates a correction, and N indicates no correction. Thus, in the first regime, for example, a report

from type

after an audit by the statutory auditor appears as information set

to the tax auditor. In the second regime, the same situation yields information set

.

Figure summarizes the timing of events in our model.Footnote14

3. Results

3.1. Equilibrium Reporting and Audit Probabilities

The game described in the previous section is an inspection game with two auditors. Inspection games have only pure-strategy equilibria for extremely low or high inspection costs. Thus, the inspectors never or always audit, and the inspectee always or never reports falsely. We do not consider these equilibria because they are rarely descriptive of real-world audit and reporting behavior. Therefore, we concentrate on mixed-strategy equilibria in which the two auditors employ a probabilistic audit strategy, and some taxpayer types randomize their reporting behavior.Footnote15 In Table , we present the taxpayer types' payoffs in both regimes for undominated reporting and auditing strategies given statutory audit probability and tax audit probability

.

Table 2. Taxpayer types' payoffs. and

The resulting equilibrium reporting and audit probabilities are displayed in Table . In the following, we first explain the reporting behavior of taxpayers (Panel A of Table ) and then the behavior of auditors (Panel C of Table ); we then compare the two information regimes. All mathematical derivations are displayed in detail in online Appendix 1.

Table 3. Results

Regarding the taxpayer's reporting probabilities, we denote as the probability that type z submits report

in a mixed-strategy equilibrium. For example,

denotes the probability that type

makes a report

.

Taxpayers with high book income and low tax income will always report truthfully because there is no incentive to deviate. Thus, is always equal to one.

Taxpayers with high book and high tax income (type (1, 1)) will never report because the payoff from this report will be less than the payoff from an honest report. Instead, they randomize between honestly reporting

and noncompliance with tax law

. As long as their financial statements are of low or medium importance, these taxpayers conduct both conforming and nonconforming tax avoidance, i.e., in equilibrium, they are indifferent between downward managing only tax income (nonconforming tax avoidance,

) and downward managing both book and tax income (conforming tax avoidance,

). Only if the importance of financial statements is high (

) will taxpayers stop conducting conforming tax avoidance and randomize between honest reporting and nonconforming tax avoidance. Thus, our model mirrors the empirical observation that an increasing importance of financial statements (e.g., due to increasing capital market pressure) reduces taxpayers' willingness to conduct conforming tax avoidance (Badertscher et al., Citation2019).

Taxpayers with low book and high tax income (type (0, 1)) have both an incentive to upward manage their book income and to downward manage their tax income. However, the statutory and tax auditors anticipate this behavior and set their audit probabilities so high that the report from type (0, 1) is (except in one case) not part of an equilibrium. In addition, due to the low equilibrium statutory audit probability of reports

, the expected payoff of this report is higher than the payoff of the honest report

such that the latter report is never part of an equilibrium. Thus, taxpayers of type (0, 1) randomize only between reporting

and

. When the importance of financial statements is high, this type of taxpayer reports even

with a probability of one.

Finally, taxpayers with low book and low tax income (type (0, 0)) will never report because the payoff from this report will be less than the payoff from an honest report. This taxpayer type has an incentive to upward manage his book income. In equilibrium, he randomizes between the honest report

and report

. When the importance of financial statements is high, this type of taxpayer even pays taxes for earnings that do not exist, i.e., the taxpayer reports

with a positive probability. Thus, our model also covers the case that is empirically described in Erickson et al. (Citation2004), who find that many firms include overstated financial accounting earnings in their tax returns.

To determine the reporting probabilities of taxpayers, we use the auditors' objective functions. In equilibrium, when a taxpayer is audited with a positive probability, the statutory (tax) auditor must be indifferent between auditing and not auditing a reported valuation (

) after observing a specific report

(information set i). Thus, the expected benefit of finding an incorrectly reported valuation conditional on observing a specific report (information set) must be identical to the cost of conducting the audit. This implies that taxpayers set their reporting probabilities such that for each report (information set), the ratio of the probability of an incorrect report (information set) and the probability of a true report (information set) is equal to the auditors' cost ratio (

for the statutory auditor and

for the tax auditor).Footnote16

Next, we describe the equilibrium behavior of auditors (Panel C of Table ). We start with the notation. The statutory auditor's auditing probabilities for the reports and

are denoted by

and

, respectively. Accordingly, the tax auditing probabilities for the tax auditor in regime 1 for information sets with

,

and

are given by

and

. In regime 2, the tax auditor's information also contains knowledge of whether the auditor has corrected the financial statement valuation (variable c). Thus, we have to consider the probabilities

,

, and

. Note that the information set

cannot occur because reports

will never be audited in equilibrium by the statutory auditor. If

is observed, then the tax auditor knows that the initial report was

and the correct b-valuation is

.

Intuitively, the tax and statutory auditors will never audit reported valuations where detected misreporting does not offer them any benefits in terms of their objective functions. Thus, the tax auditor will never audit a tax report , and the statutory auditor will never audit a financial statement report

.

In equilibrium, auditors determine the (positive) audit probabilities such that the taxpayers are indifferent between correct and incorrect reporting. The tax auditor's probability of auditing a reported valuation after observing the information set

in regime 1 (information set

in regime 2) is determined such that type (1, 1) is indifferent between reports

and

.

Similarly, the tax auditor's probability of auditing a reported valuation after observing the information set

in regime 1 (information set

in regime 2) is determined such that type (0, 1) is indifferent between reports

and

. In equilibrium, we find that

. Thus, the tax auditor audits a reported valuation

with a higher probability when the information set contains book–tax differences, which is in line with the empirical findings of Mills and Sansing (Citation2000). The reason is that the taxpayer (0, 1) sacrifices the opportunity to obtain a high book value when reporting

instead of reporting

. If the report

is nevertheless part of an equilibrium, then the tax audit probability for this report must be lower to compensate for this disadvantage.

Accordingly, we determine the statutory auditor's audit probabilities. The probabilities that the statutory auditor audits a reported valuation after observing

and

are chosen such that taxpayer type (0, 0) is indifferent between reporting

and

when financial statements are of low or medium importance and indifferent between reporting

,

, and

when financial statements are of high importance. Similar to the tax auditor, the statutory auditor also audits reports without book–tax differences with a lower probability (

).

We now compare the equilibrium behavior depending on whether the tax auditor is informed about the statutory auditor's adjustments (regime 1) or not (regime 2). When financial statements are of low importance, the tax auditor's additional information results in a reduced audit probability . The information set

can only originate from taxpayer types (0, 0) and (0,1) (see Panel C, Table ). However, the tax audit affects the expected payoff only of type (0, 1) because the taxpayer type (0, 0) is truly a low-tax type. When taxpayer type (0,1) reports

and the statutory auditor audits this report, the auditor will correct the book value and inform the tax auditor of the adjustment such that the tax auditor receives the information set

. Now, recall that the auditor sets the audit probability such that the taxpayer is indifferent between correct and incorrect reporting. Thus, the tax auditor chooses the audit probability

such that taxpayer type (0, 1) is indifferent between reporting

and

. The disadvantage of reporting

is that the taxpayer faces a higher statutory audit probability because

and thus a higher risk that the upward management of book income is detected. Therefore, in this case, a lower tax audit probability for the information set

is sufficient to make the taxpayer indifferent between correct and incorrect tax reporting.

The tax auditor's improved information also affects taxpayers' reporting probabilities. For example, as explained above, the taxpayer type (0, 1) is now indifferent between reporting and

, whereas report

is dominated by report

without the additional information concerning statutory audit adjustments. However, the individual reporting probabilities may change based on the additional information, but the unconditional probability of incorrect tax reporting for the total population remains unchanged. The underlying rationale is as follows. In equilibrium, all taxpayers choose their reporting probabilities such that the tax auditor is indifferent between auditing and not auditing a report

after observing a specific information set. This implies that for each information set (with an interior solution for the audit probability), the ratio of the probability of an incorrect tax information set and the probability of a true tax information set is equal to the tax auditors' cost ratio

. Because

does not depend on the additional information and there are no corner solutions for the tax auditor under both information regimes when the importance of financial statements is low, this condition holds for all information sets independent of the information regime. Thus, the unconditional probability of incorrect tax reporting (= the sum of the probabilities of incorrect tax information sets) is the same in both information regimes and equals the product of the cost ratio

and the unconditional probability of correctly reporting

, i.e.,

(for a formal proof, see online Appendix 1.3).

When financial statements are of medium importance, the additional information even allows the tax auditor to reduce the audit probability to zero because in contrast to the setting with a low importance of financial statements, taxpayer type (0, 1) does not report

in equilibrium. The latter report is now dominated by

due to the increased importance of financial statements. Thus, the information set

can originate only from taxpayer type (0, 0), i.e., a true low-tax type (see Panel C, Table ), and

must hold in equilibrium. Moreover, due to this corner solution regarding the tax audit probability

, it follows that the unconditional probability of incorrect tax reporting must be lower than that without the additional information (for a formal proof, see online Appendix 1.3). Recall that taxpayers set their reporting probabilities such that for each information set (with an interior solution for the audit probability), the ratio of the probability of an incorrect tax information set and the probability of a true tax information set is equal to the tax auditors' cost ratio

(see above). However, in the case of

, the ratio of the probability of an incorrect tax information set and the probability of a true tax information set must be

. Therefore, taxpayers' probability of incorrect tax reporting must be lower than that without the additional information.

Finally, when financial statements are of high importance, the additional information affects neither audit probabilities nor reporting probabilities. The reasons for this potentially surprising result are as follows. The information sets and

can originate only from taxpayer type (0, 0) (see Panel C, Table ). Thus, the tax audit probability for these reports must equal zero in equilibrium. However, the tax auditor already audits the information set

with zero probability in the setting without information exchange. Thus, there is no change in this respect. In addition, the tax auditor sets

such that taxpayer type (1, 1) is indifferent between reporting

and

. As the payoff of this taxpayer type does not differ between the two information regimes,

must hold. Similarly, the statutory auditor's probabilities also do not change because they follow from the same calculus under both information regimes. Finally, the determination of the reporting probabilities also cannot change because each correct and incorrect tax information set originates from the same taxpayer types in both regimes (e.g., the correct tax information sets

originate from types (1, 0) and (0, 0), while the incorrect set only originates from type (1, 1), which exactly matches the reporting structure for information set

in regime 1).

Accordingly, the additional information may but not necessarily must change the equilibrium reporting and audit behavior. This leads to the question of whether the additional information may help to improve audit efficiency or even worsen it. In the next section, we therefore define two efficiency measures and compare the effects of the information regimes on these measures.

3.2. Efficiency Effects

3.2.1. Efficiency measures

We analyze two measures that characterize tax audit efficiency. These measures are defined as follows.

(1) Tax audit frequency (TA): The tax audit frequency (TA) is defined as the unconditional probability of a tax audit

Since, in equilibrium, a tax audit only takes place after observing an information set i with

, in regime 1, we can write (the superscripts (1) and (2) denote the respective information regimes)

Similarly, in regime 2, we obtain

(2) Lost tax revenue (LTR): The probability of taxing a t = 1-taxpayer who reports

with a final valuation

can be interpreted as ‘lost tax revenue’ (LTR):

LTR measures the fraction of incorrect tax reporting that is not detected by the tax auditor and can be regarded as an inverse measure of tax revenue. A low value of LTR implies a high tax revenue, and vice versa. LTR considers all t = 1-types that submit reports leading to information sets i with

and that will not be audited by the tax auditor. In regime 1, LTR is thus given by

Similarly, in regime 2, we obtain

The relation between the two efficiency measures depends on the strategic interactions among the three players: LTR and TA will move in opposite directions if taxpayers only mildly react to changes in the tax auditors' activities. For example, a reduced TA entails an increase in LTR. However, if taxpayers adjust their tax reporting strategy with changes in the tax auditor's activity, then LTR and TA may also move in the same direction. The following results demonstrate that both relations can appear in our setting.

3.2.2. Information exchange and audit efficiency

The results regarding the effect of the described information exchange between the statutory and the tax auditors on LTR and TA are displayed in Table , Panel D and summarized in the following propositions.

Proposition 1

(Negative tax revenue effect)

Consider firms with a low importance of financial statement valuation (). Then, the following tax efficiency relations hold:

| (1) |

| ||||

| (2) |

| ||||

Proof.

See online Appendix 2.1.

The reasons for the negative tax revenue effect are as follows. The observable corrections induce a lower tax audit probability when tax auditors observe the information set . However, as shown in Table , the probabilities of tax misreporting do not change for any taxpayer type when financial statements are of only low importance. Instead, due to the anticipated information exchange between the statutory and tax auditor, the taxpayers only change their financial statement reporting probabilities. For example, because of the lower tax audit probability for the information set

, taxpayer type (0, 1) now takes the risk of reporting

and reduces the frequency of reporting

by the same amount.

In sum, taxpayers do not change their tax misreporting probability, but tax auditors reduce their tax audit probability. Thus, LTR increases and TA decreases from regime 1 to regime 2. The overall effect of information exchange is therefore ambiguous because the net benefit (tax revenues minus audit costs) can increase or decrease depending on whether the increase in LTR is weighted more heavily than the decrease in tax audit costs.Footnote17

Proposition 2

(Efficient information effect)

Consider firms with a medium importance of financial statement valuation . Then, the following tax efficiency relations hold:

| (1) |

| ||||

| (2) |

| ||||

Proof.

See online Appendix 2.2.

With a medium importance of financial statements, only taxpayer type changes reporting probability in response to information exchange between the statutory and the tax auditor (see Table ). In contrast to the setting with low importance of financial statements, taxpayer type

finds report

more attractive than report

because the statutory auditor may downgrade

to

. Thus, taxpayer type

sacrifices the chance of a low tax valuation to obtain a favorable financial statement valuation with certainty and randomizes only between reports

and

. As a consequence, corrected financial statements together with a reported low tax valuation are a perfect indicator of a truthful tax report (as the information set

can only stem from type

). Therefore, the tax auditor will not audit these reports; the tax audit probability decreases.

Moreover, due to the informativeness of uncorrected financial statements together with a reported low tax valuation (information set ) tax misreporting is also reduced. The tax auditor audits reports with information set

, and therefore, taxpayers of type

reduce their probability of reporting

by the same amount as they increase their probability of reporting

in equilibrium. Thus, tax misreporting decreases. This is the difference from the setting with a low importance of financial statements. With a low importance of financial statements, taxpayers of type

reduce their probability of reporting

by the same amount as they increase their probability of reporting

(instead of

), which has obviously no effect on the tax misreporting probability.

In sum, in the case of medium importance of financial statements, providing information about the statutory auditor's corrections to the tax auditor induces both higher tax revenue and lower audit frequency. Thus, the effect of information exchange is unambiguous, i.e., the net benefit (tax revenues minus audit costs) always increases.

The question arises whether the taxpayer and the statutory auditor have incentives to collude, which might attenuate the positive effect of information exchange. The taxpayer and statutory auditor might agree to conceal corrections in the financial statements in the audit report, which means reporting information set instead of

. Such collusion, however, cannot be beneficial to the taxpayer, because the tax audit probability for information set

is positive instead of zero for information set

.

Proposition 3

(No information effect)

Consider firms with a high importance of financial statement valuation . Then, the following tax efficiency relations hold:

| (1) |

| ||||

| (2) |

| ||||

Proof.

See online Appendix 2.3.

When financial statements are of high importance, the information regarding the statutory auditor's corrections does not affect the equilibrium audit and reporting probabilities. Specifically, the tax auditor will audit neither for the information set nor

. Thus, it is not surprising that the additional information has no effect on tax audit efficiency.

The following figures illustrate the change of TA (Figure ) and LTR (Figure ) for a variation in in a numerical example.Footnote18 We vary

from high over medium to low importance of financial statement valuation.

Figure 2. Tax audit frequency (TA) in regime 1 (black, solid) and regime 2 (blue, dashed). High importance of financial statements for , medium importance for

and low importance for

. Parameters: p = 0.8,

,

,

,

,

![Figure 2. Tax audit frequency (TA) in regime 1 (black, solid) and regime 2 (blue, dashed). High importance of financial statements for ωT∈[0,1.5], medium importance for ωT∈(1.5,2.1) and low importance for ωT≥2.1. Parameters: p = 0.8, θT=3/7, θS=9/11, ωB=1.5, FB=0.6, FT=0.4](/cms/asset/2a59f78b-1848-450c-8090-d6a0e02f82a2/rear_a_2108094_f0002_oc.jpg)

Figure 3. Lost tax revenue (LTR) in regime 1 (black, solid) and regime 2 (blue, dashed). High importance of financial statements for , medium importance for

and low importance for

. Parameters: p = 0.8,

,

,

,

,

![Figure 3. Lost tax revenue (LTR) in regime 1 (black, solid) and regime 2 (blue, dashed). High importance of financial statements for ωT∈[0,1.5], medium importance for ωT∈(1.5,2.1) and low importance for ωT≥2.1. Parameters: p = 0.8, θT=3/7, θS=9/11, ωB=1.5, FB=0.6, FT=0.4](/cms/asset/c4d1dea3-8ab7-4676-a3a8-1f788b9b1526/rear_a_2108094_f0003_oc.jpg)

affects TA and LTR directly via the audit probabilities of the statutory and the tax auditor, while it does not affect the taxpayers' reporting probabilities. Specifically, a higher

increases all nonnegative tax audit probabilities and decreases the probability of a statutory audit of report

in the case of high importance of financial statements. The latter probability, however, affects neither TA nor LTR. As a consequence, we observe in Figure that a lower importance of financial statements increases TA. For the same reason, LTR decreases in

given high, medium or low importance of financial statements. Moreover, the tax audit probabilities are smooth as the importance of financial statements changes from high to medium and from medium to low. Therefore, the graph of TA is also smooth in

. However, tax reporting switches to more aggressive reports with changes in the importance of financial statements. Thus, LTR exhibits upward jumps when the importance of financial statements decreases from high to medium and from medium to low.

4. Additional Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Additional Analysis

Proposition 2 demonstrates that providing the tax auditor with additional information can be efficient with respect to the tax system. However, additional information may change the reported financial valuation and may thus have a negative effect on financial statement quality. In our setting with a conservative statutory auditor, the ex ante probability of overstated financial statements (PO) is the appropriate measure of financial statement quality. We define it as follows:

(4)

(4)

The first line of term (Equation4

(4)

(4) ) denotes the probability that inflated financial statements reported by taxpayer type (0, 1) survive the statutory audit. The second line contains the same probability for taxpayer type (0, 0).

Comparing PO in regimes 1 and 2 yields the following result:

Proposition 4

(Financial statement quality effect)

Consider firms with a medium importance of financial statement valuation . Then, the following relation holds:

Proof.

See online Appendix 2.4.

The result shows that overstated financial statements appear more frequently in a setting with better informed tax auditors. In such a setting, the taxpayers' shift from incorrect tax reporting to earnings management is not compensated by more intensive statutory audits.

The reason for this finding is subtle. If the tax auditor decides to audit a low reported tax valuation based on the information set , the probability of correct reports is reduced compared to information regime 1 because the corrected report of type

with information set

must not be considered any longer. Since in equilibrium the ratio of probabilities of incorrect to correct reports must remain the same, type

reduces his report

and increases the probability of reporting

instead.

In sum, the tax audit efficiency enhancing effect comes at the cost of a reduction in financial statement quality as the probability of overstated financial assets increases. This could result in a potential conflict between the regulators who oversee statutory audits and tax audits. To the best of our knowledge, research thus far has neither examined nor discussed potential conflicts between the two audit regulators. However, there is an extensive body of research concerning a potential conflict that may arise between tax and financial statement regulators. On the one hand, there is some evidence that a high book–tax conformity would reduce the incentive to conduct tax avoidance and thus may be beneficial in terms of higher tax revenues (e.g., Atwood et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, there is evidence that book–tax alignment may result in less informative financial statements (e.g., Atwood et al., Citation2010; Hanlon et al., Citation2005). These opposing consequences of book–tax conformity may thus lead to a conflict between the two regulators. However, there is also some evidence that the objectives of financial statement and tax regulators are not opposing but complementary as the government can be seen as a large minority shareholder (Desai, Citation2005) and book–tax alignment would reduce both tax avoidance and earnings management (Tang, Citation2015). Thus, it is empirically unclear whether there is actually a conflict between tax and financial statement regulators regarding book–tax conformity. However, our model clearly suggests that the objectives of regulators who oversee statutory audits and tax audits are not complementary but are (at least partially) in conflict because information exchange between both auditors will improve tax audit efficiency (higher tax revenues and lower tax audit costs) but increase earnings management. Thus, our findings extend the prior discussion by showing that the controversy about the tradeoff between lower tax avoidance and informativeness of financial statements carries over to the regulation of tax and statutory audits.

4.2. Discussion

We begin our discussion by critically reflecting on five key assumptions. First, our model is based on the simplifying assumption of a perfect audit technology. With imperfect audit technologies, auditors may make two types of mistakes. On the one hand, they may not detect misreporting. In our model, this will reduce the expected cost of misreporting for taxpayers. Thus, auditors will have to increase their audit probabilities to make taxpayers indifferent between correct and incorrect reporting, and taxpayers will increase the probability of misreporting to make the auditor indifferent between auditing and not auditing a report. On the other hand, auditors may assess additional taxes even if the taxpayer is truly a low-tax type. If one assumes high audit costs or error correction costs at the expense of the taxpayer, then this could lead to tax overreporting as is shown for the example in Rhoades (Citation1997). However, our model focuses on the effect of information on the statutory auditor's adjustments on tax audit efficiency, and although imperfect audit technologies will make the model more realistic, it will not change the qualitative results of our model. Thus, we decided to not integrate imperfect audit technologies.

Second, we assume a conservative statutory auditor who does not benefit from detecting understated financial statements. As taxpayer type never understates financial statements, relaxing this assumption would only be crucial for the results in section 3.2 if taxpayer type

refrained from reporting

for a non-conservative statutory auditor. For a high importance of financial statements, type

never reports

. Therefore, the assumption of a conservative statutory auditor does not affect proposition 3. For a low or medium importance of financial statements, Table and online Appendices 1.1.1 and 1.2.1 show the following: (1) Types

and

both report

in regimes 1 and 2. (2) The equilibrium reporting probabilities of type

are not uniquely defined but allow a reporting probability

. The efficiency results in propositions 1 and 2, however, hold for all

. Note that with

, the statutory auditor's conditional probability of an understated financial statement valuation after observing report

also converges to zero. As a consequence of positive audit costs, even a non-conservative statutory auditor will not audit report

. Depending on the statutory auditor's benefits from detecting understatements, the equilibrium interval for

may become smaller, but the efficiency implications in propositions 1 and 2 remain unaffected. In sum, our results do not critically depend on the assumption of a conservative statutory auditor.

Third, we model the probability distribution of taxpayer types in a simplified fashion. By assuming that has the characteristics

and

jointly with

, we can define a conformity measure p between tax and financial statement valuation that is independent of the probability of the true tax (t) or financial statement (b) values. Furthermore, this implies that the probability for any b-value is also 0.5, so that in turn the probability distributions for true b- and t-values are also not affected by the conformity measure p. If we deviate from this simplification, the equilibrium audit probabilities of both auditors remain the same because they are derived from the taxpayer types' indifference between cheating and not. However, the equilibrium reporting probabilities of the taxpayer types will change, as the auditors' indifference equations become different if the probability distribution of taxpayer types changes. Although this quantitatively changes our efficiency measures, it should have no effect on our qualitative results.

Fourth, as a difference from the earnings management literature, misreporting for financial or tax accounting purposes does not induce direct costs in our model. Reducing the benefit that taxpayers receive from misreporting by direct costs decreases auditors' audit probabilities because lower probabilities will then be sufficient to make taxpayers indifferent between correct and incorrect reporting. The reporting probabilities of the taxpayers are not affected because they are determined such that the auditor is indifferent between auditing and not auditing given a specific report/information set. Because the incentives of the auditor do not depend on the taxpayers' cost function, the introduction of ‘misreporting costs’ will not affect the reporting probabilities. However, most important, introducing additional costs will not affect the qualitative results regarding the investigated information effect and will thus not yield additional insights. Therefore, we refrained from including these costs.

Fifth, to reduce the complexity of the paper, we considered only tax auditors with medium-powered incentives. When tax auditors have very high incentives (i.e., low audit costs), the additional information does not affect tax audit efficiency because tax auditors do not reduce their audit probabilities. By contrast, when tax auditors have very low incentives, the additional information may even lead to a higher tax audit frequency. In this case, tax revenues may rise. For a detailed analysis, we refer to Blaufus et al. (Citation2020). However, as we have argued above (see footnote 11), assuming medium tax auditor incentives is a very reasonable assumption because neither low nor high tax auditor incentives are consistent with empirical observations in practice. High incentives would imply that tax auditors do not differentiate between reports with and without book–tax differences in their tax auditing decisions; low incentives would imply that all taxpayers of type t = 1 would report when no information sharing between the statutory and the tax auditor is allowed.

Accordingly, although our key assumptions obviously simplify the real reporting and audit environment, our results also apply to more complex environments. Our main result is that information on statutory audit adjustments can indeed, in the case of a medium importance of financial statements, improve tax audit efficiency: it reduces tax audit frequency and simultaneously increases tax revenues. However, this comes at the cost of reduced financial statement quality because the probability of overstated financial values increases. Moreover, when financial statement valuations are of only low importance, the additional information can even reduce tax revenues.

That additional information in terms of the statutory auditor's audit adjustments may reduce the efficiency of the tax audit seems surprising, because one could assume that the tax auditor can always ignore the additional information if she is worse off with it. However, this is only true if the tax auditor could commit ex ante to a certain audit strategy conditional on the observed information. Such a commitment would include to commit to not use the information in certain circumstances. This is not realistic for two reasons. First, from an institutional perspective, it seems to be impossible to publicly release tax audit strategies that include a detailed description of when to use/not to use statutory auditor information. Second, if the information is available, then it is ex post (at the time of the tax audit) always optimal for the tax auditor to consider it. That is, the tax auditor is forced to play sequentially optimally in equilibrium. Thus, the only way to avoid potential efficiency losses due to additional information is to abstain from information sharing between the statutory auditor and the tax auditor.

One lesson from our study for the regulator is therefore that information sharing is only beneficial in terms of tax efficiency if on average the potential efficiency gains from information sharing derived in our study dominate the potential efficiency losses. If the regulator decides to require that the tax auditor is provided access to statutory audit adjustments, the regulator could on the one hand require the audit report to be extended by a description of the significant adjustments. On the other hand, it may be sufficient to require that the adjusting entries required as a result of the statutory audit be clearly identifiable to the tax auditor. Then, the tax auditor could make the audit probability of a position dependent on statutory audit adjustments to this position.

A further question that arises from our model's results is whether we can derive testable predictions for empirical research. Ideally, our propositions would be tested in an experimental lab environment. Using lab experiments, one could empirically test all predictions regarding the effects of the additional information on tax revenues, tax audit frequency, and audit and reporting probabilities. Furthermore, using archival audit data, one could test whether tax audit frequency varies with cross-country differences in the obligation to file the audit report together with the tax return (see Table in the Appendix) or whether statutory auditors condition their audit probability of a position on book–tax differences as suggested by our model. In addition, experimental surveys of tax auditors could test whether tax auditors respond to information about statutory audit adjustments as predicted by our model, i.e., by reducing their audit probability in the case of no book–tax differences where the book value is adjusted downward by the statutory auditor.

Moreover, note that our model predicts and can therefore explain the following empirical observations that have been found in prior archival research. First, reports with book–tax differences are audited with a lower probability (Mills & Sansing, Citation2000). Second, the increasing importance of financial statements decreases conforming tax avoidance, i.e., tax planning, by reducing both financial and tax income (Badertscher et al., Citation2019). Third, with the increasing importance of financial statements, some firms have begun reporting a high tax income to mask the upward management of book income (Erickson et al., Citation2004).

Regarding analytical research, our model significantly extends prior research by integrating a strategic statutory auditor in tax compliance games. Based on this model, there are many avenues for future analytical research. For example, it would be interesting to examine the effects of the information exchange on statutory audit efficiency in more detail. In addition, it would be worthwhile to examine the effects of changing book–tax conformity, tax rates, penalties, and uncertainty regarding the objective functions of the players on tax audit efficiency.

5. Conclusion

Is it possible to simultaneously increase tax revenues and reduce tax audit frequency simply by providing the tax auditor with access to statutory audit adjustments? To examine this question, we integrate two novel features in a tax compliance game. In the first modification of the standard inspection game, the tax auditor can observe the financial statements that are already audited by a statutory auditor. The statutory auditor is a strategic player who acts conservatively, i.e., he or she corrects only overstatements. Thus, firms can misreport both their book and their tax income. In the second modification, we extend this model by assuming that the tax auditor additionally receives a report from the statutory auditor that contains information on audit adjustments regarding the firm's book value. The report is an informative signal about the true tax value of a firm because a firm's incentive to conduct upward management of book value depends on the respective tax value.

If tax auditors have medium-powered incentives and firms' financial statement valuation is of medium importance, then we indeed find that providing the tax auditor with access to statutory audit adjustments reduces tax audit frequency and increases tax revenues. In this case, granting access to statutory audit adjustments clearly improves the efficiency of the tax audit regime. Information sharing between statutory and tax auditors could therefore be a policy instrument to combat tax evasion and increase the efficiency of tax audits. However, we also find that the tax audit efficiency enhancing effect comes at the cost of lower financial statement quality as the probability of overstated financial values increases. Moreover, if financial statements are of only low importance to firms, the additional information can even reduce tax revenues. Thus, an implication for the regulator is that information sharing is only beneficial in terms of tax audit efficiency if on average the potential efficiency gains from information sharing derived in our study dominate the potential efficiency losses.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (193.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Hofmann (editor), two anonymous reviewers, Joachim Gassen, Laszlo Goerke, Kyungha Lee, Ulf Schiller, Barbara Schöndube-Pirchegger, Alfred Wagenhofer, participants of the ARFA – Workshop 2015, the GEABA – Symposium 2015, the EAA – Conference 2016, the VHB - Conference 2016, and the EISAM Workshop on Accounting and Economics 2016 for helpful comments.

Supplemental Data and Research Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2022.2108094.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Our model is formulated such that it covers risky legal tax planning and (illegal) tax evasion. In the model, the difference is simply represented by the amount of penalties. In the case of risky legal tax planning, penalties are interest payments (above the market rate) that have to be paid on back tax payments after the audit. In the case of tax evasion, penalty payments include, in addition to interest payments, criminal penalties. In the paper, we often simply refer to incorrect tax reporting to cover both risky tax planning and illegal tax evasion.

2 We do not examine pure-strategy equilibria in which the tax auditor never or always audits and the taxpayer always or never evades taxes because these equilibria are rarely observed in real-world audit and reporting behavior.

3 See, for example, Zerni et al. (Citation2012), Deng et al. (Citation2014), and André et al. (Citation2016).

4 To avoid having an excessively complex model, we exclude agency conflicts from the analysis. The effect of agency problems (among shareholders or between shareholders and managers) on corporate tax avoidance is analyzed, for example, in Chen and Chu (Citation2005), Crocker and Slemrod (Citation2005), and Jacob et al. (Citation2021).

5 We do not address the taxpayer's uncertainty about the correct valuations in this paper. An analysis of tax uncertainty can be found, for example, in Graetz et al. (Citation1986), Beck and Jung (Citation1989), Beck et al. (Citation1996), Mills et al. (Citation2010), or De Simone et al. (Citation2013).

6 This assumption is made for ease of exposition. The uniform distribution is sufficient to produce a variety of results that certainly hold under more general assumptions.

7 See, for example DeFond and Subramanyam (Citation1998), Heninger (Citation2001), Kim et al. (Citation2003), Cahan and Zhang (Citation2006), and Venkataraman et al. (Citation2008).

8 See Watts (Citation2003).

9 In section 4.2, we show that auditor conservatism simplifies the exposition of the equilibria in our game but is not critical for the efficiency results in propositions 1 to 3.

10 There are typically implicit incentives for assessing additional taxes during tax audits because the effectiveness of the tax audit staff is evaluated with respect to additional taxes ‘earned’ from tax audits (Alissa et al., Citation2014; Blaufus et al., Citation2022). In some countries, explicit incentives also exist (Kahn et al., Citation2001). However, we acknowledge that the legal function of a tax audit is to discover all relevant facts that are necessary to find the correct taxable income, even if this reduces the tax payment.

11 High tax auditor incentives would imply that tax auditors do not differentiate between reports with and without book–tax differences in their tax auditing decisions (Blaufus et al., Citation2020). This is not what one observes in reality (Mills & Sansing, Citation2000). Thus, high incentives do not seem to describe audit behavior in practice. Moreover, when tax auditor incentives are low, all taxpayers of type t = 1 report when no information exchange takes place between the statutory and the tax auditor. Again, this is not consistent with observations in practice. Thus, the assumption that tax auditors have medium incentives remains the most reasonable assumption.

12 Gassen and Fülbier (Citation2015) report an average debt ratio of 62% for European private firms.

13 The same problem of tractability would arise if we were to assume that the taxpayer is uncertain about the parameters of the auditors' objective functions. See Reinganum and Wilde (Citation1988) for such an approach.

14 The timeline illustrates that we assume a traditional tax audit rather than a permanent or contemporary tax audit under a cooperative compliance regime.

15 It may be necessary to consider mixed- and pure-strategy equilibria when we compare the two information regimes. However, such a case does not appear in the following analysis because we do not consider extremely low tax auditor incentives.

16 Recall that and

.

17 In our model, this simply depends on whether is larger than, lower than or equal to one.

18 The properties discussed below hold generally. A proof is available upon request.

References

- Alissa, W., Capkun, V., Jeanjean, T., & Suca, N. (2014). An empirical investigation of the impact of audit and auditor characteristics on auditor performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(7), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.06.003

- André, P., Broye, G., Pong, C., & Schatt, A. (2016). Are joint audits associated with higher audit fees?. European Accounting Review, 25(2), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2014.998016

- Atwood, T., Drake, M. S., Myers, J. N., & Myers, L. A. (2012). Home country tax system characteristics and corporate tax avoidance: International evidence. The Accounting Review, 87(6), 1831–1860. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50222

- Atwood, T., Drake, M. S., & Myers, L. A. (2010). Book-tax conformity, earnings persistence and the association between earnings and future cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.11.001

- Badertscher, B. A., Katz, S. P., Rego, S. O., & Wilson, R. J. (2019). Conforming tax avoidance and capital market pressure. The Accounting Review, 94(6), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52359

- Bayer, R. C. (2006). A contest with the taxman–the impact of tax rates on tax evasion and wastefully invested resources. European Economic Review, 50(5), 1071–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2005.03.002

- Beck, P. J., Davis, J. S., & Jung, W. O. (1996). Tax advice and reporting under uncertainty: Theory and experimental evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(1), 49–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/care.1996.13.issue-1

- Beck, P. J., Davis, J. S., & Jung, W. O. (2000). Taxpayer disclosure and penalty laws. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 2(2), 243–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/1097-3923.00038

- Beck, P. J., & Jung, W. O. (1989). Taxpayers' reporting decisions and auditing under information asymmetry. The Accounting Review, 64(3), 468–487.

- Blaufus, K., Lorenz, D., Milde, M., Peuthert, B., & Schwäbe, A. N. (2022). Negotiating with the tax auditor: Determinants of tax auditors' negotiation strategy choice and the effect on firms' tax adjustments. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 97(2), Article 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2021.101294

- Blaufus, K., Schöndube, J. R., & Wielenberg, S. (2020). Strategic interactions between tax and statutory auditors and different information regimes: Implications for tax audit efficiency, February 2022. Available at http://www.arqus.info/mobile/paper/arqus_249.pdf.

- Cahan, S. F., & Zhang, W. (2006). After Enron: Auditor conservatism and ex-Andersen clients. The Accounting Review, 81(1), 49–82. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2006.81.1.49

- Chen, K. P., & Chu, C. C. (2005). Internal control versus external manipulation: A model of corporate income tax evasion. The RAND Journal of Economics, 36(1), 151–164.

- Crocker, K. J., & Slemrod, J. (2005). Corporate tax evasion with agency costs. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9-10), 1593–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.08.003

- DeFond, M. L., & Subramanyam, K. (1998). Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25(1), 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(98)00018-4

- Deng, M., Lu, T., Simunic, D. A., & Ye, M. (2014). Do joint audits improve or impair audit quality? Journal of Accounting Research, 52(5), 1029–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12060

- Desai, M. A. (2005). The degradation of reported corporate profits. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196705

- De Simone, L., Sansing, R. C., & Seidman, J. K. (2013). When are enhanced relationship tax compliance programs mutually beneficial? The Accounting Review, 88(6), 1971–1991. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50525

- Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. S. (1994). Honesty and evasion in the tax compliance game. The RAND Journal of Economics, 25(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555850

- Erickson, M., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2004). How much will firms pay for earnings that do not exist? Evidence of taxes paid on allegedly fraudulent earnings. The Accounting Review, 79(2), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2004.79.2.387

- Gassen, J., & Fülbier, R. U. (2015). Do creditors prefer smooth earnings? Evidence from European private firms. Journal of International Accounting Research, 14(2), 151–180. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar-51130

- Graetz, M. J., Reinganum, J. F., & Wilde, L. L. (1986). The tax compliance game: Toward an interactive theory of law enforcement. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 2(1), 1–32.

- Hanlon, M., Kelley Laplante, S., & Shevlin, T. (2005). Evidence for the possible information loss of conforming book income and taxable income. The Journal of Law and Economics, 48(2), 407–442. https://doi.org/10.1086/497525

- Hanlon, M., Maydew, E. L., & Shevlin, T. (2008). An unintended consequence of book-tax conformity: A loss of earnings informativeness. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46(2-3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.09.003

- Heninger, W. G. (2001). The association between auditor litigation and abnormal accruals. The Accounting Review, 76(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2001.76.1.111

- IRS (2019a). Congressional budget justification and annual performance report and plan – fiscal year 2020. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/266/02.-IRS-FY-

- IRS (2019b). IRS funding cuts compromise taxpayer service and weaken enforcement. https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-personnel

- Jacob, M., Rohlfing-Bastian, A., & Sandner, K. (2021). Why do not all firms engage in tax avoidance?. Review of Managerial Science, 15(2), 459–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00346-3

- Kahn, C. M., Silva, E. C., & Ziliak, J. P. (2001). Performance-based wages in tax collection: The Brazilian tax collection reform and its effects. The Economic Journal, 111(468), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00594

- Kim, J. B., Chung, R., & Firth, M. (2003). Auditor conservatism, asymmetric monitoring, and earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20(2), 323–359. https://doi.org/10.1506/J29K-MRUA-0APP-YJ6V

- Mills, L. F., Robinson, L. A., & Sansing, R. C. (2010). FIN 48 and tax compliance. The Accounting Review, 85(5), 1721–1742. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.5.1721

- Mills, L. F., & Sansing, R. C. (2000). Strategic tax and financial reporting decisions: Theory and evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 17(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/(ISSN)1911-3846

- Nessa, M., Schwab, C., Stomberg, B., & Towery, E. (2020). How do IRS resources affect the corporate audit process? The Accounting Review, 95(2), 311–338. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52520

- Niggemann, F. P. (2020). Mandatory book-tax conformity and its effects on strategic reporting and auditing. Available at SSRN.

- Reinganum, J. F., & Wilde, L. L. (1986). Equilibrium verification and reporting policies in a model of tax compliance. International Economic Review, 27(3), 739–760. https://doi.org/10.2307/2526692

- Reinganum, J. F., & Wilde, L. L. (1988). A note on enforcement uncertainty and taxpayer compliance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(4), 793–798. https://doi.org/10.2307/1886076

- Rhoades, S. C. (1997). Costly false detection errors and taxpayer rights legislation: Implications for tax compliance, audit policy and revenue collections. The Journal of the American Taxation Association, 19(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.1999.74.1.63

- Rhoades, S. C. (1999). The impact of multiple component reporting on tax compliance and audit strategies. The Accounting Review, 74(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.1999.74.1.63

- Sansing, R. C. (1993). Information acquisition in a tax compliance game. The Accounting Review, 68(4), 874–884.

- Slemrod, J. (2016). Tax compliance and enforcement: New research and its policy implications (Ross School of Business Paper, 1302).

- Tang, T. Y. (2015). Does book-tax conformity deter opportunistic book and tax reporting? An international analysis. European Accounting Review, 24(3), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2014.932297

- Venkataraman, R., Weber, J. P., & Willenborg, M. (2008). Litigation risk, audit quality, and audit fees: Evidence from initial public offerings. The Accounting Review, 83(5), 1315–1345. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2008.83.5.1315

- Watts, R. L. (2003). Conservatism in accounting. Part I: Explanation and implications. Accounting Horizons, 17(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2003.17.3.207

- Wenzig, H. (1983). Statutory audit and tax audit [in German: Wirtschaftspruefung und steuerliche Betriebspruefung]. Betriebs-Berater, 38(31), 1935–1940.

- Zerni, M., Haapamäki, E., Järvinen, T., & Niemi, L. (2012). Do joint audits improve audit quality? Evidence from voluntary joint audits. European Accounting Review, 21(4), 731–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2012.678599

Appendix.

Legal Obligations: Overview

Table A1. Legal obligations to file financial accounting statements and statutory auditor reports to the tax administration