?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We examine whether board independence improves the readability of annual reports. Using a sample of 11,938 firm-year observations over the period 1997–2016, we empirically show that board independence decreases the readability of annual reports. This result is consistent with the notion of managerial avoidance of costly board monitoring. We also run an array of cross-sectional tests to understand the settings in which the association is either more or less pronounced. Even though managerial ability and SEC’s Plain English Rule of 1998 improve readability, we find that the negative relationship between board independence and readability continues to persist. Our results also reveal that directors’ tenure and CEO duality attenuate the board independence–readability relationship, while CEO tenure enhances this association. Overall, our findings provide additional insights into the link between board independence and annual report readability.

1. Introduction

We examine the association between independent boards and the readability of annual reports. We find that a higher level of board independence decreases readability. Extant research in corporate governance indicates that an independent board is an effective monitor for ensuring more disclosures and greater transparency (e.g. Armstrong et al., Citation2010; Goh et al., Citation2016). Prior literature also documents a positive relationship between independent boards and voluntary disclosures, informativeness of earnings and an improved information environment due to increased monitoring (improvement of disclosure hypothesis).Footnote1 Nevertheless, several theoretical studies raise concerns regarding the efficacy of monitoring by an independent board to improve disclosure quality (Adams & Ferreira, Citation2007; Drymiotes, Citation2011). Overall, these studies suggest that independent boards may not necessarily encourage greater disclosure quality as managers may obfuscate information to avoid costly board monitoring (avoidance of monitoring hypothesis). Given the conflicting evidence and predictions, the issue of whether or not independent directors increase the readability of annual reports is an open question. To provide empirical evidence in response to the question, we examine the direction of the relationship between annual report readability and board independence, and the conditions that affect the strength of the association.

We explore the relationship using a sample of 11,938 firm-year observations for the period 1997–2016. To measure the readability of annual reports, we primarily use the Bog indexFootnote2 developed by Bonsall et al. (Citation2017). A higher score on this index represents lower readability of annual reports. To measure the level of board independence, we use the proportion of independent directors on a firm’s board. We find a positive association between board independence and the Bog index score. This finding suggests that the higher the fraction of independent directors on the board, the lower the readability of annual reports. Specifically, we find that, in terms of the standard deviation, the decrease in readability is about 8.41%. The magnitude of this result is non-trivial and consistent with the findings of prior studies (e.g. Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Hasan, Citation2020).

To address endogeneity concerns, we follow Goh et al. (Citation2016) and Knyazeva et al. (Citation2013), using board connections and board locations as instruments of board independence. Goh et al. (Citation2016) argue that directors sitting on other boards are more likely to be connected and to have significant influence on the board structure. We also use board locations as an instrument as the supply of independent directors is based on directors serving in nearby locations. Using the instrumental variable approach, we find that our instrumented board independence reduces the readability of annual reports. In addition to instrumental variables, we use three other tests to allay concerns that our results are driven by firm-related omitted variables. Firstly, we include the lagged value of the readability measure as an additional control variable. This method can mitigate omitted-variable bias as both the contemporaneous and lagged values of readability are affected by the same unobservable, time-invariant characteristics. Our results remain substantially similar after including this additional control.

Secondly, we use firm and year fixed effects regression to control for any omitted time-invariant firm characteristics. We find that the coefficient of board independence continues to have the expected sign and to yield significant results. Thirdly, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) incentives and compensation could play a critical role in how information is disclosed to boards and in how effective boards are in monitoring managers (Bergstresser & Philippon, Citation2006; Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation2012). We therefore include CEO incentive-related variables: CEO delta (CEO_DELTA), CEO vega (CEO_VEGA) and CEO overall pay (CEO_PAY) as additional controls. The first two variables measure CEO pay sensitivity to stock performance (delta) and stock volatility (vega). Overall, our results are robust to this approach and the tests support the validity of our baseline results.

In the next stage, we examine the robustness of our findings using alternative measures of board independence and readability. For the alternative measure of board independence, we construct a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the proportion of independent directors on the board is at least 50%, and 0 otherwise. We also construct two additional proxies for independent board co-option to substantiate our baseline findings. Specifically, we examine whether or not co-optedFootnote3 independent boards reduce the readability of annual reports. Coles et al. (Citation2014) argue that executive compensation increases excessively with a co-opted board. We also find that the readability of annual reports decreases in firms where the proportion of co-opted independent directors increases. For alternative readability measures, we use four different proxies: the Fog index, 10-k file size, the Flesch index and the Kincaid index. We then rerun our baseline models using these alternative measures, finding that the negative relationship between board independence and annual report readability remains largely unchanged. Overall, these results reinforce the robustness of our baseline findings.

Finally, we explore the settings in which the impact of board independence on annual report readability is more pronounced or less pronounced. Firstly, we follow Hasan (Citation2020) and test the role of managerial ability. We find that the impact of board independence continues to remain pronounced although managerial ability improves readability. Secondly, we show that board independence significantly reduces readability, even with the overall improvement in readability after the adoption of the Plain English Rule of 1998. Thirdly, we examine whether or not directors’ tenure has any influence on our baseline relationship. We argue that long tenures help in the acquisition of monitoring skills. Consistent with this argument, we find that the impact of board independence on annual report readability is more (less) pronounced in short-tenured (long-tenured) boards. Fourthly, we investigate how CEO duality (when a CEO is also the board chair) affects annual report readability. Brickley et al. (Citation1997) argue that CEO duality ensures the effectiveness of board co-ordination and efficiency in information processing and disclosures. Consistent with their findings, we find that readability improves with CEO duality. Finally, evidence suggests that long-tenured CEOs are more entrenched with rent-seeking activities and choose weaker governance structures (Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation1998). We conduct a cross-sectional analysis to test this and find that the impact of board independence is stronger for firms with long-tenured CEOs.

This study contributes to the literature in several important ways. Firstly, we show the strategic motive of managers in choosing the complexity of the narrative in their disclosures. Few studies document strategic reporting using a textual analysis of narrative disclosures. For example, Li (Citation2008) finds that annual reports are complex and less readable in periods of low earnings compared to periods of persistent high earnings. Lo et al. (Citation2017) link earnings management with poor readability. Humphery-Jenner et al. (Citation2019) indicate that managers strategically reduce readability to avoid litigation risk. We extend this literature by linking the annual report readability construct with board independence. Secondly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that empirically links lexical features of narrative disclosures with board independence. We empirically test and find supporting evidence for the insights of Adams and Ferreira (Citation2007), Drymiotes (Citation2011) and Goldman and Slezak (Citation2006). Consistent with the predictions of these studies, we extend the board independence literature by showing how board independence can negatively affect the information environment. Finally, we also extend the board independence literature by showing how managerial ability, the Plain English Rule of 1998, CEO tenure, CEO duality and directors’ tenure can affect the relationship between board independence and annual report readability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the relevant literature and theoretical background. Section 3 presents the sample and research design. Section 4 describes the baseline results, identification strategy and robustness checks. Section 5 presents the cross-sectional settings in which the baseline impact is either more pronounced or less pronounced. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. The Relationship Between Independent Boards and Annual Report Readability

In recent years, policy makers and academics have paid more attention to the complexity and readability of annual reports and their link with stock prices (e.g. Callen et al., Citation2013; Lee, Citation2012). The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), for example, issued the Plain English Rule of 1998 (SEC Rule 421 [d]) for new prospectuses. Moreover, the SEC encourages firms to adopt the plain English principle in their filings (Loughran et al., Citation2009). Several studies examine the effects of readability. Callen et al. (Citation2013), for example, find that poor readability of annual reports hinders the timely discovery of stock prices, resulting in delayed price adjustments and higher future returns. Similarly, Lee (Citation2012) documents that value-relevant, earnings-related information of textually complex reports follows a delayed and inefficient adjustment in stock prices. Chen and Tseng (Citation2021) find that the lower the readability of narrative disclosures in the notes in an annual report, the greater the bond yield spread. Caglio et al. (Citation2020) find that integrated reporting readability is associated with a high market valuation. Athanasakou et al. (Citation2020) find a negative effect on the cost of equity capital at lower levels of disclosure, and a positive effect at higher levels of disclosure. This study further suggests that a positive relationship between higher levels of disclosure and cost of equity indicates ‘uninformative clutter increasing the cost of equity capital’ (p. 27).Footnote4

One strand of the literature addresses the antecedents and motives for annual report readability. Consistent with an incomplete revelation hypothesis (Bloomfield, Citation2002; Bloomfield, Citation2008), several studies report that hiding poor earnings and information-obfuscating behavior are important motives for making disclosure less readable (e.g. Humphery-Jenner et al., Citation2019; Li, Citation2008; Lo et al., Citation2017). For example, Li (Citation2008) finds that annual reports are complex and less readable when firms have poor performance. The complexity primarily emanates from information-hoarding behavior so that investors find it difficult to detect bad news and earnings manipulation (Lo et al., Citation2017). Moreover, Humphery-Jenner et al. (Citation2019) show that managers strategically reduce the readability of annual reports when they have higher exposure to securities class action lawsuits (SCAs). Nguyen (Citation2021) reports similar strategic behavior by firms with a high magnitude of tax avoidance. To reduce the risk of exposing their tax planning, these firms strategically decrease the readability of their annual reports. In a similar vein, we study how board independence affects the readability of annual reports.

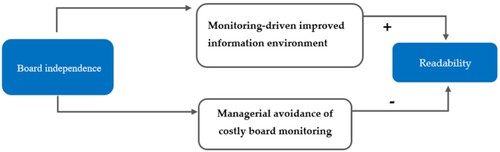

Following prior literature, we argue that the direction of the relationship between board independence and annual report readability is not clear ex ante. On one hand, readability as a disclosure choice may improve as an independent board more rigorously monitorsFootnote5 and improves the information environment. On the other hand, readability may actually decrease as managers try to avoid costly monitoring by an independent board ().

The view that a higher level of board independence leads to an improvement in disclosure has received support from several studies (Beasley, Citation1996; Byrd & Hickman, Citation1992; Dechow et al., Citation1996). Given the significance of independent directors, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX Act) mandates that companies form a 100% independent audit committee. This mandate is motivated by the premise that independent directors establish an effective internal control mechanism to review financial auditing and reporting. As a result, the information environment will become more transparent. Several studies report that independent boards encourage more corporate disclosures which reduce information asymmetry (e.g. Armstrong et al., Citation2010; Goh et al., Citation2016). Prior studies also show that earnings management decreases when board independence increases (Klein, Citation2002).

An alternative view, however, is that a higher level of board independence may lead to more manipulation and a decrease in annual report readability as managerial actions may serve to counteract and reduce the efficacy of monitoring by an independent board (Adams & Ferreira, Citation2007; Drymiotes, Citation2007, Citation2011). In their model, Adams and Ferreira (Citation2007) identify the role of two board functions, monitoring and advisory, in interaction between the CEO and the board. A manager may have different project preferences to those of shareholders, giving rise to moral hazard problems. Assuming that board monitoring is rigorous, Adams and Ferreira (Citation2007) argue that managers do not reveal firm-specific information to a more independent board for the following reason: let us suppose that managers communicate firm-specific information that the board can use to provide better advice (i.e. its advisory role). Ironically, the same information could be used by the board to evaluate all possible projects. The more precise the information, the higher the likelihood that the board will intervene in decision making (i.e. its monitoring role), increasing the risk that managers may lose the benefits from their control. Given that such a scenario dissuades managers from revealing information, Adams and Ferreira (Citation2007) conclude that a higher level of board independence will reduce information sharing and precision.

In a related vein, Drymiotes (Citation2011) analytically examines the interaction between a higher level of monitoring and manipulative activities by managers. He considers a firm that hires a manager to supply some unobservable productive inputs that result in firm outputs. The firm evaluates and compensates the manager based on a performance report generated by its internal control and performance evaluation systems. The board’s monitoring can make this noisy information report about the firm’s actual outputs less noisy (i.e. can ensure greater information precision). Drymiotes (Citation2011) argues that the manager also has the technology and knowledge (means) to undermine the board’s monitoring. In addition to having in-depth knowledge about the firm’s internal control and evaluation systems, managers interact with board members and gain further knowledge about the board’s future actions for monitoring purposes. A manager may also ‘divert attention from the performance report or make it more difficult or costly for directors to obtain information … ’ (Drymiotes, Citation2011, p. 236). Overall, the manager engages in more manipulation to mitigate the effects of monitoring efforts which leads to additional noisy performance reports.

Other studies also delve into similar concerns and examine how regulatory changes to improve the information environment negatively affect disclosure quality. In their model, Goldman and Slezak (Citation2006) assume that a manager can manipulate and bias information using firm resources. Specifically, they find that regulatory changes may not necessarily have their intended effect. In some cases, policies, such as increases in penalties that are intended to increase disclosure quality, may actually reduce it. The board’s incentive to apply the incentive contract for manipulation control decreases when manipulation is made more difficult by the regulator (e.g. SEC). This, in turn, induces the manager to obfuscate the results. Likewise, Aghion and Tirole (Citation1997) show a link between the level of the principal’s formal authority and the amount of communication. Specifically, increasing the formal authority of the board (i.e. the principal) may decrease the incentive for management (i.e. the agent) to share a greater level of communication. In a similar vein, Levitt and Snyder (Citation1997) show that the probability of interventionist actions by the board (the principal) may induce the manager to provide less information.Footnote6 Some recent empirical studies also support this prediction. Athanasakou et al. (Citation2020) suggest that clutter in readability increases with an increase in the regulatory demands for increased disclosure. Taken together, all these studies suggest that independent boards may not necessarily improve disclosure quality when managers try to undermine a board’s monitoring role. Instead, managers may engage in information-hoarding behavior. This view, thus, suggests that readability has a negative association with board independence.

Overall, we see that the link between board independence and readability is not clear a priori; therefore, we investigate the question empirically using the following alternative hypothesis:

H1: Annual report readability is negatively associated with an increase in board independence.

3. Sample and Research Design

3.1. Sample

We obtain data on board characteristics from Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and begin our sample from 1997 as data are available from this period onwards. We obtain the readability score (BOG_INDEX) of 10-K files for the period 1994–2016 from the Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval (EDGAR) system’s records.Footnote7 The intersection of these two databases constitutes our initial sample of 30,805 firm-year observations. To address reverse causality, we consider a year lag for the explanatory variables. For example, board characteristics in 1997 are matched with the annual report readability index score in 1998. This procedure gives us a sample of 26,671 firm-year observations. Furthermore, to construct our regression sample, we collect firm-characteristic variables from Compustat, Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and SDC Platinum databases and managerial ability scores from Peter Demerjian’s website (Demerjian et al., Citation2012). We follow a standard filtering procedure to limit our sample to CRSP stock codes of 10 and 11 and eliminate regulated industries, that is, financials and utilities. After considering a year lag of our firm characteristic variables, we merge the firm-characteristic dataset with our initial sample. After removing 14,733 missing observations from all variables, we obtain our final sample of 11,938 firm-year observations for the period 1997–2016.

3.2. Research Design

To examine whether or not independent boards decrease the readability of annual reports, we estimate the following baseline model:

(1)

(1)

The variables specified in Equation (1)Footnote8 are described in the following sub-sections. The key variables are BOG_INDEX, the primary measure of annual report readability, and IND_BOARD, the degree of board independence. We include industry fixed effects based on two-digit Standard Industry Classification (SIC) industries in the US to control for any time-invariant omitted industry characteristics and year fixed effects to control for the time effect.Footnote9

3.2.1 Measuring annual report readability

Our primary measure of annual report readability is the Bog index (BOG_INDEX). Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) developed this multifaceted measure of disclosure to evaluate the difficulty of reading 10-K reports. Specifically, this measure evaluates whether or not a 10-K report avoids the use of weak verbs, complex words, jargon, the passive voice, overused words and lengthy sentences. The measure has three components: Sentence Bog, Word Bog and Pep. Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) modeled this as follows:

(2)

(2)

In model (2) above, the Sentence Bog captures the difficulty of reading longer sentences. It is estimated as the square of the average sentence length, scaled by a 35-word limit. The Word Bog captures two components: word difficulty and plain English-style problems. Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) estimate this by taking the ratio of the summation of these two components multiplied by 250 and the number of words.Footnote10 Finally, the Pep captures the writing attributes (i.e. the use of interesting words and names) related to the understanding of the text. Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) estimate Pep by summing the writing attributes, multiplying by 25 and dividing the sum by the total number of words and sentence variation. Overall, the Sentence Bog and Word Bog identify any sentence- and word-related reading difficulties, while the Pep considers readability and simplicity of writing attributes from the readers’ perspective. Given that the Bog index captures the multifaceted attributes of 10-K reports, this index is more rigorous than other traditional measures (Bonsall et al., Citation2017). A higher score on this index represents less readable annual reports. Following the broad accounting and finance literature, we use some alternative readability measures for robustness checks. For example, following Loughran and McDonald (Citation2014), we include 10-K file size (10K_FILE_SIZE) which is the natural logarithm of 10-K net file size in megabytes, as one of the measures. Following prior literature (Biddle et al., Citation2009; Dougal et al., Citation2012; Lawrence, Citation2013; Lehavy et al., Citation2011; Li, Citation2008), we also include the Fog index (FOG), the Flesch index (FLESCH) and the Flesch–Kincaid index (KINCAID) as alternative measures.

3.2.2. Measuring board independence

We estimate board independence as the ratio of the number of independent directors sitting on the board to the total number of directors. This proportion of independent directors on the board (IND_BOARD) is the primary measure in this study. In sensitivity analysis, following Anderson et al. (Citation2004), we also construct an indicator variable (IND_BOARD_ALT) that takes the value of 1 if the proportion of independent directors on the board is at least 50%, and 0 otherwise.

3.2.3. Control variables

We include several control variables related to firm and board attributes in our empirical specifications. Following prior studies (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2004), we control for BOARD_SIZE, which is measured as the natural logarithm of the total number of directors on the board. For firm characteristics affecting the readability of annual reports, we control for several variables following Hasan (Citation2020), Li (Citation2008) and Lo et al. (Citation2017). We measure the size of a firm (SIZE_FIRM) as the natural logarithm of market capitalization. We estimate market capitalization by multiplying the closing share price with the number of shares outstanding. We also control for the market-to-book ratio (MARKET_BOOK), which is the ratio of (market value of equity + book value of liabilities) and (book value of assets). Consistent with prior studies (Hasan, Citation2020; Li, Citation2008; Lo et al., Citation2017), we control for both of these variables as we expect differences in annual report readability between smaller and larger firms, and between high growth and low growth firms. Similarly, we include the age of firms (COMPANY_AGE), financial performance (PROFITABILITY), earnings volatility (EAR_VOL), and return volatility (VOL_RETURN). We estimate COMPANY_AGE by considering the number of years since a firm first appeared on the CRSP database. PROFITABILITY is measured as the ratio of income before extraordinary items to total assets and is expected to be negatively associated with annual report readability. We use the standard deviation of operating earnings over the last five years as a measure of EAR_VOL, and the standard deviation of monthly stock returns for VOL_RETURN. Consistent with Hasan (Citation2020), we expect that both types of volatility will reduce annual report readability, whereas higher company age will improve their readability. We also control for firm characteristics related to complexity, and special items and circumstances. For complexity, we include the numbers of business segments (SEGMENT_BUS), geographic segments (SEGMENT_GEO), and non-missing items in Compustat (NONMISS_ITEMS). For these three measures of complexity, we take the natural logarithm and expect that the complexity of firms to have a negative association with annual report readability. For special items (SPECIAL_ITEMS), we calculate the ratio of special items to total assets. We expect that firms with a lower value (a higher negative number) of special items are more likely to have complex or less readable annual reports. We control for two additional special circumstances using the indicator variables, MA_DUMMY and DELAWARE. MA_DUMMY is defined as a variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is an acquirer in the SDC Platinum Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) database, and 0 otherwise. We include DELAWARE as different corporate laws in the US state of Delaware drive different levels of annual report readability (Daines, Citation2001). This indicator variable takes the value of 1 if a firm is incorporated in Delaware, and 0 otherwise. We expect these indicator variables to have a negative association with annual report readability. Finally, following Hasan (Citation2020), we include managerial ability (MA_RANK) as an additional control. We extract the decile rank of managerial ability from Demerjian et al. (Citation2012). We expect a positive association between managerial ability (MA_RANK) and annual report readability.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

reports the summary statistics for the key variables used in this study. In panel A, we find that the mean (median) value of our primary readability measure (BOG_INDEX) is 83.837 (84.000), which is consistent with the mean (median) of 82.847 (83.000) of Hasan (Citation2020). Panel B summarizes the board characteristics. The number of directors (NO_DIRECTORS) on the board has a mean (median) value of 8.970 (9.000), while the fraction of independent directors (IND_BOARD) has a mean (median) value of 0.700 (0.727). These board characteristics are consistent with recent studies (Ferreira et al., Citation2011; Goh et al., Citation2016). For instance, Goh et al. (Citation2016) report mean (median) values for NO_DIRECTORS and IND_BOARD of 9.555 (9.000) and 0.657 (0.667), respectively. , Panel C presents the summary statistics for firm characteristics, with these also consistent with the results of Hasan (Citation2020) and Lo et al. (Citation2017). For example, we find that the size of firm (SIZE_FIRM) has a mean (median) value of 7.552 (7.426), while the market-to-book ratio (MARKET_BOOK) has a mean (median) value of 1.758 (1.369). also shows that volatility of return (VOL_RETURN) has a mean (median) value of 0.113 (0.098), while MA_DUMMY and MA_RANK have mean (median) values of 0.310 (0.000) and 0.571 (0.600), respectively.

Table 1. Key summary statistics

presents the correlation matrix for the key variables. We find that BOG_INDEX has a positive correlation with IND_BOARD, implying that board independence has a negative association with annual report readability. For most of the control variables, we find significant correlations with BOG_INDEX at a 1% level of significance with the expected signs. As predicted, SIZE_FIRM, EAR_VOL, VOL_RETURN, SEGMENT_BUS, SEGMENT_GEO, NONMISS_LOG, MA_DUMMY and DELAWARE have a positive association with BOG_INDEX (i.e. a negative association with annual report readability). We also find that BOARD_SIZE, COMPANY_AGE, PROFITABILITY and SPECIAL_ITEMS have a negative correlation with BOG_INDEX. We further find that correlations among the control variables are modest which tentatively suggests a low probability of multicollinearity problems.

Table 2. Correlation matrix

4.2. Baseline Results

presents the relationship between IND_BOARD and BOG_INDEX. In this table, column (1) shows the estimations excluding industry and year fixed effects; column (2) shows the estimations excluding industry fixed effects; column (3) shows the results excluding year fixed effects; and column (4) shows a full model including both industry and year fixed effects. The t-values are reported in parentheses, with standard errors clustered at the firm level and corrected for heteroscedasticity. Across all regressions, we find the coefficients of IND_BOARD to be positive and significant at the 1% level. As mentioned in Section 3.2.1, an increase in the Bog index indicates a decrease in annual report readability. Thus, these results suggest that readability decreases when the representation of independent directors on the board increases. In terms of economic significance, the coefficient of IND_BOARD (3.611) in column (4) indicates that an increase in board independence reduces annual report readability by about 4.31% (3.611/83.837) of the mean. This change is economically meaningful.Footnote11 In other words, based on standard deviations for IND_BOARD (0.169) and BOG_INDEX (7.256), our results suggest a decrease in annual report readability by about 8.41%.Footnote12 Overall, our baseline results provide strong supporting evidence for our hypothesis that board independence has a negative association with annual report readability.

Table 3. Baseline results – independent boards and annual report readability

Furthermore, the results of the regressions, as reported in all columns, show that most control variables have their expected signs (as discussed in Section 3.2.3). For instance, firm size (SIZE_FIRM), volatility of earnings and returns (EAR_VOL and VOL_RETURN), and operational complexity (SEGMENT_BUS, NONMISS_LOG and MA_DUMMY) have positive associations with BOG_INDEX. Consistent with the literature (e.g. Hasan, Citation2020; Upadhyay & Sriram, Citation2011), we also find that large boards (BOARD_SIZE) and mature and profitable firms (COMPANY_AGE and PROFITABILITY) have a positive (negative) association with annual report readability (BOG_INDEX).

4.3. Identification Strategy

A caveat in our baseline findings is that we are unable to claim whether or not the relationship between board independence and annual report readability is causal. Prior studies (Armstrong et al., Citation2014; Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation2003) argue that the information environment and board independence could be jointly determined. For instance, Armstrong et al. (Citation2014) point out that firms may proactively decrease information asymmetry to attract more independent directors who would otherwise be reluctant to join an opaque information environment. Moreover, when independent directors are appointed, the firm’s information environment also improves in terms of the board’s immediate actions. We attempt to address this endogeneity issue with instruments that generate an exogenous shock to board independence but that may not have any direct relationship with annual report readability.

Following Goh et al. (Citation2016) and Knyazeva et al. (Citation2013), we use board connections and board locations as instruments for board independence. We define board connections (BOARD_CONNECTION) based on directors’ social networks. Specifically, our proxy is estimated as the proportion of directors on at least one other board being higher than the sample’s median proportion of independent directors for the year. Following Goh et al. (Citation2016), we argue that directors sitting on other boards, especially with a proportionally higher level of independent directors, are more likely to be connected.Footnote13 Our intuition behind this instrument is that directors’ networks have a significant influence on board structure. We include board locations (BOARD_LOCATION) as the second instrument. We define BOARD_LOCATION as the number of independent directors located in the state where the headquarters of firms are located in the year. The argument for including this as an instrument is that the supply of independent directors could be based on directors serving in nearby locations. Goh et al. (Citation2016) argue that neither of these instruments have any direct association with the information environment; therefore, they should both be candidates for valid instruments for board structure.

presents the results for the two stages of the instrumental variable approach. Column (1) reports the first-stage regression results for IND_BOARD. We find that both the instruments are statistically significant in column (1). In column (2), the instrumented values are used in the second stage where we find that instrumented IND_BOARD is positive and significant. These results bolster our baseline findings.Footnote14

Table 4. Identification strategy – board connections and locations as instruments

In addition to the instrumental variable approach, we use additional tests to allay the concerns that other firm-related omitted variables drive our results. The use of industry and year fixed effects in our baseline models controls for the time effect and industry-related, time-invariant omitted variable bias. To allay any bias related to firm-related omitted variables, we use three additional tests. First, we include BOG_INDEX at time t − 1 as an additional control variable in Equation (1). This method can mitigate omitted-variable bias, because both BOG_INDEX at time t and BOG_INDEX at t − 1 are affected by the same unobservable time-invariant characteristics. Column (1) of shows this result. We find that IND_BOARD still has a positive sign and is significant at the 1% level. Second, we use firm- and year-fixed effects regression to control for any omitted time-invariant firm characteristics. Column (2) reports this result where we find that the coefficient of IND_BOARD is positive and significant. Thirdly, as CEO incentives and compensation could play a critical role in how management discloses information to boards and how effectively boards can monitor managers (Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation2012), we include CEO incentive-related variables. Specifically, we use CEO delta (CEO_DELTA), CEO vega (CEO_VEGA) and CEO overall pay (CEO_PAY) as additional controls in equation Equation(1)(1)

(1) .Footnote15 CEO_DELTA is defined as the dollar change in CEO wealth for a 1% change in stock price, while CEO_VEGA is the change in CEO wealth for a 0.01 change in the standard deviation of returns. Column (3) summarizes the results after including these three CEO incentive-related variables. We find that the coefficient of IND_BOARD continues to be positive and significant. Overall, these tests and their results largely mitigate the concern that our baseline results are driven by omitted-variable bias.

Table 5. Identification strategy – addressing omitted variable bias

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis16

presents the sensitivity analysis of our baseline findings. As shown in Panel A, in examining the robustness of these findings, we consider an alternative measure for board independence and two other board-co-option measures. Firstly, following Anderson et al. (Citation2004), we construct a dummy variable (IND_BOARD_ALT) that takes the value of 1 if at least 50% of directors on the board are independent, and 0 otherwise. Column (1) shows the results. We find that the estimated coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. Secondly, following Coles et al. (Citation2014) we use two board co-option measures: the fraction of co-opted independent directors (CO_OPTED_IND_FRACTION) and the tenure-weighted co-option ratio (CO_OPTED_IND_TENURE). We estimate CO_OPTED_IND_FRACTION as the number of independent directors appointed after a CEO assumes office, divided by the total number of directors on the board. For CO_OPTED_IND_TENURE, we consider the ratio of the total tenure of co-opted independent directors to the total tenure of all directors. Hwang and Kim (Citation2009) argue that if independent directors are co-opted to the board after a CEO assumes office, the appointments are nothing more than a CEO’s box-ticking strategy. In this situation, CEOs are entrenched and the monitoring role of directors becomes mostly ineffective. Coles et al. (Citation2014) find that these co-opted boards diminish performance–turnover sensitivity and excessively increase compensation. Huang et al. (Citation2019) show that board co-option has a negative relationship with clawback adoption which, in turn, is likely to negatively affect financial reporting quality.Footnote17 In a similar vein, Cassell et al. (Citation2018) find that a higher level of co-option in audit committees leads to more financial restatements and a higher level of absolute discretionary accruals. To the extent that higher annual report readability captures financial reporting quality, board co-option will also have a negative effect on readability. The results with both these co-option measures are reported in , Panel A, columns (2)–(3). We find that the coefficients for co-option proxies are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. These results lend support to the conjecture that annual report readability decreases significantly in co-opted independent boards.

Table 6. Sensitivity analysis

Table 6a. Sensitivity analysis

, Panel B shows the results using several alternative proxies for annual report readability. We use four alternative measures: FOG_INDEX, 10K_FILE_SIZE, FLESCH_INDEX and KINCAID_INDEX.Footnote18 The higher the values for FOG_INDEX, 10K_FILE_SIZE and KINCAID_INDEX, the lower the readability of annual reports, whereas the higher the value for FLESCH_INDEX, the higher the annual report readability. The results are reported in , Panel B, columns (1)–(4). We find that the coefficients are all statistically significant and that they preserve the expected signs. Overall, we find robust evidence that board independence is negatively associated with annual report readability.

5. Cross-sectional Analyses19

Our results thus far show that an increase in board independence decreases the readability of annual reports. In this section, we cross-sectionally analyse the moderating role of managerial ability, the Plain English Rule of 1998, board tenure, and CEO duality and tenure.

5.1. Managerial Ability

Prior empirical research reveals that more able managers maximize shareholders’ wealth to a greater extent than their less able counterparts (Chemmanur et al., Citation2009; Demerjian et al., Citation2012). Demerjian et al. (Citation2012) show that less able managers engage in more earnings management and that earnings quality increases as managerial ability increases. Consistent with this evidence, Hasan (Citation2020) finds that high-ability managers improve the readability of annual reports. Motivated by this finding, we examine how managerial ability influences our baseline relationship. Following Hasan (Citation2020), we use the decile rank (MA_RANK), extracted from Demerjian et al. (Citation2012), as the proxy for managerial ability. The key variables of interest are MA_RANK, IND_BOARD and the interaction term (IND_BOARD × MA_RANK). We report the results in , column 1. We find that IND_BOARD is negative and not significant, whereas the interaction term is positive and significant. This implies that, even though managerial ability improves annual report readability (with a negative and significant coefficient for MA_RANK), the impact of board independence on annual report readability continues to persist.

Table 7. Cross-sectional tests – managerial ability and SEC’s Plain English Rule of 1998

5.2. The Plain English Rule of 1998

We examine how the relationship between board independence and annual report readability changes over time. The US SEC adopted the Plain English Rule of 1998 requiring firms to use understandable language in their prospectus filings. Although prospectus filings were the initial target, the SEC then encouraged the application of the plain English rule to all filings including 10-Ks. The impact of this rule on 10-K reports appears evident, with 10-K reports becoming more readable after the adoption of the Plain English Rule of 1998 (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2014). This section reports our findings on whether or not the plain English rule plays a moderating role between board independence and annual report readability. We create a dummy variable, PLAIN_RULE_1998, that takes the value of 1 for the post-1998 firm-year observations, and 0 otherwise. The key variables of interest are PLAIN_RULE_1998, IND_BOARD and IND_BOARD × PLAIN_RULE_1998. We report the results in , column 2. We find that IND_BOARD is positive but not significant, whereas the interaction term is positive and significant. This implies that board independence reduces annual report readability even with an overall improvement of readability after adoption of SEC’s Plain English Rule of 1998 (as the coefficient of PLAIN_RULE_1998 is negative and significant).

5.3. Directors’ Tenure

The monitoring role of directors is considered an acquired skill which becomes more developed over time. Thus, long-tenured boards are considered to be more effective monitors. Conversely, Anderson et al. (Citation2004) argue that managers can influence long-tenured boards more easily than short-tenured boards. As a result, oversight decreases with an increase in directors’ tenure. We examine these competing arguments by interacting directors’ tenure and independent directors’ tenure with IND_BOARD. On one hand, if the interaction terms are significantly negative and the net effect, including the constituent terms, remain positive, long-tenured boards have increased monitoring skills and mitigate the relationship between board independence and annual report readability. On the other hand, if the interaction terms are positive and the net effect, including the constituent terms, remain positive, managers’ influence on long-tenured corporate boards results in weakened monitoring and less readability of annual reports. We use two measures for directors’ tenure: BOARD_TENURE and IND_BOARD_TENURE. We define BOARD_TENURE as the total number of years that directors have served on the board, divided by the number of directors, while IND_BOARD_TENURE is the total number of years that independent directors have served on the board, divided by the total number of independent directors. displays the results, with columns (1) and (2) showing that both interaction terms (IND_BOARD × BOARD_TENURE and IND_BOARD × IND_BOARD_TENURE) are negative and significant, while the sum of the coefficients of IND_BOARD and the interaction terms remain positive. These results suggest that directors’ tenure can mitigate the association between independent boards and annual report readability. In other words, this implies that independent directors have improved monitoring skills as their tenure increases on boards, resulting in an improvement in annual report readability.

Table 8. Cross-sectional tests – Directors’ tenure

5.4. CEO Duality and Tenure

When a CEO is also the board chair, the situation of CEO duality arises. A general notion exists that CEO duality could hinder the monitoring functions of boards. This argument is based on the entrenchment theory of agency conflict (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Jensen, Citation1993). On the positive side, CEO duality may provide a clear direction for, and co-ordination of, board functions and efficiency in information processing and disclosure (Brickley et al., Citation1997). We cross-sectionally test both these arguments by examining the role of CEO duality in the relationship between board independence and annual report readability. We create an indicator variable, CEO_DUALITY, that takes the value of 1 if the CEO is also the board chair, and 0 otherwise. The key variables are IND_BOARD, CEO_DUALITY and the interaction term IND_BOARD × CEO_DUALITY. , column (1) shows the results. We find that the interaction term is negative and significant, while the sum of the coefficients of IND_BOARD and IND_BOARD × CEO_DUALITY remain positive. These results suggest that CEO duality mitigates the association between independent boards and annual report readability. In other words, in firms where the CEO is also the board chair, the annual report readability improves. This finding supports the efficiency theory of CEO duality.

Table 9. Cross-sectional tests – CEO duality and tenure

CEO tenure is another important determinant of the board’s functioning. Prior empirical literature shows that the monitoring role of an independent board becomes ineffective in the presence of long-tenured CEOs. Generally, long-serving CEOs, with an interest that is different to that of shareholders, choose a weaker governance structure (Hermalin & Weisbach, Citation1998). Consistent with this argument, we hypothesize that the impact of board independence on readability is more pronounced in firms with long-tenured CEOs. To examine this, we define a dummy variable, CEO_TENURE_HIGH, that takes the value of 1 if the CEO is serving for longer than the sample’s median tenure, and 0 otherwise. Our key variables of interest are IND_BOARD, CEO_TENURE_HIGH and the interaction term, IND_BOARD × CEO_TENURE_HIGH. , column (2) displays the results, revealing that the constituent term IND_BOARD is positive but not significant, while the interaction coefficient (IND_BOARD × CEO_TENURE_HIGH) is positive and significant. This finding suggests that the impact of board independence on annual report readability becomes more pronounced in firms with long-tenured CEOs.

6. Conclusion

This paper presents our analysis of whether an increase in board independence influences annual report readability. We provide evidence to answer this question by relating the proportion of independent directors on a board to the Bog index, a comprehensive and multifaceted readability measure. In addition to this primary proxy for annual report readability, we use other measures, comprising the Fog index, 10-K file size, the Flesch index and the Flesch–Kincaid index.

Overall, our evidence supports the hypothesis that annual report readability has a negative association with board independence. To provide additional confidence that our findings are not driven by reverse causality or correlated omitted variables, we use instruments and find that our results remain unchanged. We also conduct a firm-and year-fixed-effects regression. Our results remain substantially similar, giving further credence to our baseline findings. We also study settings in which the impact of board independence on annual report readability is either more pronounced or less pronounced. We find that the influence of board independence remains dominant even in firms with high managerial ability and after the introduction of SEC’s Plain English Rule of 1998. We further report that the impact is more pronounced in firms with long-tenured CEOs, although it is less pronounced when boards are long-tenured and the CEO is also the chair of the board.

Overall, we contribute to the strategic financial reporting literature and the board independence literature. The findings are also of value to regulators and policy makers, identifying strategic motives for changes in annual report readability and the contexts in which board independence is less effective.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful comments from Beatriz García Osma (editor) and two anonymous reviewers. We are also grateful for the comments from the anonymous reviewers of the CAAA Annual Conference 2020. This research was supported by UQ Business School, The University of Queensland and Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See for instance, Anderson et al. (Citation2004), Chen et al. (Citation2015), Ferreira et al. (Citation2011), and Klein (Citation2002). Duchin et al. (Citation2010) find that the cost of information acquisition affects the link between board independence and firm performance. Zhang and Yu (Citation2016) find that the relationship between board independence and audit quality is conditional on firm’s information environment.

2 This is a multifaceted measure of difficulty in words, sentences, and pep, which is more demanding than other traditional measures such as the fog index. Please see Section 3.2.1 for details.

3 Co-opted directors are those who are appointed after the CEO assumes his or her position.

4 Extant research links poor readability, for example, with higher product market competition (Rahman et al., Citation2023); higher stock price crash risk (Kim et al., Citation2019); a less favorable bond rating (Bonsall & Miller, Citation2017); higher cost of borrowing (Ertugrul et al., Citation2017); lower stock liquidity (Lang & Stice-Lawrence, Citation2015); higher return volatility (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2014); lower trading volume (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2011); more disagreement among small investors (Miller, Citation2010); and less efficient investments (Biddle et al., Citation2009).

5 Prior literature on the theory for board independence suggests that managers are monitored rigorously by an independent board (e.g., Adams & Ferreira, Citation2007). As the highest decision-making body in a company, the board has the legal power to review major operating, financial and strategic decisions. In the process, the board is both able and willing to revise and reject management’s proposals that the board deems to be contrary to the shareholders’ interest. As characterized by Adams and Ferreira (Citation2007, p. 218), the monitoring role of the board is defined as ‘active participation in the firm’s decision making’.

6 The agent either communicates an early warning to the principal or the principal receives the signal through intense monitoring. The principal then terminates the project based on the signal. This also results in the destruction of some of the information about the agent’s efforts. In turn, this makes it more difficult or costly to induce the agent to provide information.

7 Our source for the Bog index is Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) which is available at: https://kelley.iu.edu/bpm/activities/bogindex.html.

8 All the continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% level of significance in both tails to control for outliers.

9 We also run firm and year fixed effects, with the results reported in Section 4.3.

10 For more detailed discussion, see Bonsall et al. (Citation2017).

11 Bonsall et al. (Citation2017) and Hasan (Citation2020) report that the Bog index has less variation and, hence, a 4.31% change is economically meaningful.

12 The coefficient of IND_BOARD is 3.611. With the standard deviation of BOG_INDEX being 7.256 and the standard deviation of IND_BOARD being 0.169, this suggests an 8.41% (3.611*0.169/7.256) change in BOG_INDEX.

13 As observed by Adams and Ferreira (Citation2009), we acknowledge that social networks between directors may not be directly observable. For a detailed discussion regarding the applicability of this instrument in this setting, see Goh et al. (Citation2016).

14 We also report the diagnostic statistics for our instruments and two-stage least squares (2SLS) models in the bottom panel of . We find that the partial R2 value (0.2639) is sufficiently high and that the partial F-statistic (334.796) is higher than all the critical values. The Kleibergen–Paap Wald rk F statistic and the Kleibergen–Paap Wald rk LM statistic are both significant. Overall, these post-estimation measures suggest that our instruments are neither over/under-identified nor weakly identified.

15 We obtain data for CEO delta and CEO vega from Coles et al. (Citation2006), with the data available at: https://sites.temple.edu/lnaveen/data/.

17 As clawback adoption enables firms to compel executives to return part of their compensation in the case of accounting restatement, prior research finds that clawbacks improve financial reporting quality (Chan et al., Citation2012; Dehaan et al., Citation2013).

18 Our main variable (BOG_INDEX) is highly significant and positively associated with FOG_INDEX (0.2723), 10K_FILE_SIZE (0.3440) and KINCAID_INDEX (0.2887), and negatively associated with FLESCH_INDEX (−0.4078).

References

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2007). A theory of friendly boards. The Journal of Finance, 62(1), 217–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01206.x

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Aghion, P., & Tirole, J. (1997). Formal and real authority in organizations. Journal of Political Economy, 105(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/262063

- Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., & Reeb, D. M. (2004). Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37(3), 315–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.01.004

- Armstrong, C. S., Core, J. E., & Guay, W. R. (2014). Do independent directors cause improvements in firm transparency? Journal of Financial Economics, 113(3), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.05.009

- Armstrong, C. S., Guay, W. R., & Weber, J. P. (2010). The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2-3), 179–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001

- Athanasakou, V., Eugster, F., Schleicher, T., & Walker, M. (2020). Annual report narratives and the cost of equity capital: U.K. Evidence of a U-shaped relation. European Accounting Review, 29(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2019.1707102

- Beasley, M. S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. Accounting Review, 71(4), 443–465. https://www.jstor.org/stable/248566

- Bergstresser, D., & Philippon, T. (2006). CEO incentives and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(3), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.10.011

- Biddle, G. C., Hilary, G., & Verdi, R. S. (2009). How does financial reporting quality relate to investment efficiency? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2-3), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.09.001

- Bloomfield, R. (2002). The ‘incomplete revelation hypothesis’ and financial reporting. Accounting Horizons, 16(3), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2002.16.3.233

- Bloomfield, R. (2008). Discussion of ‘annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence’. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2-3), 248–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.04.002

- Bonsall, S. B., Leone, A. J., Miller, B. P., & Rennekamp, K. (2017). A plain English measure of financial reporting readability. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63(2-3), 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2017.03.002

- Bonsall, S. B., & Miller, B. P. (2017). The impact of narrative disclosure readability on bond ratings and the cost of debt. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(2), 608–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9388-0

- Brickley, J. A., Coles, J. L., & Jarrell, G. (1997). Leadership structure: Separating the CEO and chairman of the board. Journal of Corporate Finance, 3(3), 189–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1199(96)00013-2

- Byrd, J. W., & Hickman, K. A. (1992). Do outside directors monitor managers? Evidence from tender offer bids. Journal of Financial Economics, 32(2), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(92)90018-S

- Caglio, A., Melloni, G., & Perego, P. (2020). Informational content and assurance of textual disclosures: Evidence on integrated reporting. European Accounting Review, 29(1), 55–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2019.1677486

- Callen, J. L., Khan, M., & Lu, H. (2013). Accounting quality, stock price delay, and future stock returns. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(1), 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01154.x

- Cassell, C. A., Myers, L. A., Schmardebeck, R., & Zhou, J. (2018). The monitoring effectiveness of co-opted audit committees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(4), 1732–1765. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12429

- Chan, L. H., Chen, K. C., Chen, T. Y., & Yu, Y. (2012). The effects of firm-initiated clawback provisions on earnings quality and auditor behavior. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54(2-3), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.05.001

- Chemmanur, T. J., Paeglis, I., & Simonyan, K. (2009). Management quality, financial and investment policies, and asymmetric information. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 44(5), 1045–1079. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109009990299

- Chen, T. K., & Tseng, Y. (2021). Readability of notes to consolidated financial statements and corporate bond yield spread. European Accounting Review, 30(1), 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2020.1740099

- Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Wang, X. (2015). Does increased board independence reduce earnings management? Evidence from recent regulatory reforms. Review of Accounting Studies, 20(2), 899–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9316-0

- Coles, J. L., Daniel, N. D., & Naveen, L. (2006). Managerial incentives and risk-taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(2), 431–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.09.004

- Coles, J. L., Daniel, N. D., & Naveen, L. (2014). Co-opted boards. Review of Financial Studies, 27(6), 1751–1796. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu011

- Daines, R. (2001). Does Delaware law improve firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 62(3), 525–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00086-1

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1996). Causes and consequences of earnings manipulation: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1996.tb00489.x

- Dehaan, E., Hodge, F., & Shevlin, T. (2013). Does voluntary adoption of a clawback provision improve financial reporting quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(3), 1027–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2012.01183.x

- Demerjian, P., Lev, B., & McVay, S. (2012). Quantifying managerial ability: A new measure and validity tests. Management Science, 58(7), 1229–1248. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1487

- Dougal, C., Engelberg, J., Garcia, D., & Parsons, C. A. (2012). Journalists and the stock market. Review of Financial Studies, 25(3), 639–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr133

- Drymiotes, G. (2007). The monitoring role of insiders. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.04.003

- Drymiotes, G. C. (2011). Information precision and manipulation incentives. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 23(1), 231–258. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar-10067

- Duchin, R., Matsusaka, J. G., & Ozbas, O. (2010). When are outside directors effective? Journal of Financial Economics, 96(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.12.004

- Ertugrul, M., Lei, J., Qiu, J., & Wan, C. (2017). Annual report readability, tone ambiguity, and the cost of borrowing. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52(2), 811–836. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000187

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

- Ferreira, D., Ferreira, M. A., & Raposo, C. C. (2011). Board structure and price informativeness. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(3), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.10.007

- Goh, B. W., Lee, J., Ng, J., & Ow Yong, K. (2016). The effect of board independence on information asymmetry. European Accounting Review, 25(1), 155–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2014.990477

- Goldman, E., & Slezak, S. L. (2006). An equilibrium model of incentive contracts in the presence of information manipulation. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(3), 603–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.05.007

- Hasan, M. M. (2020). Readability of narrative disclosures in 10-K reports: Does managerial ability matter? European Accounting Review, 29(1), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2018.1528169

- Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (1998). Endogenously chosen boards of directors and their monitoring of the CEO. American Economic Review, 88(1), 96–118. https://www.jstor.org/stable/116820.

- Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2003). Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution: A survey of the economic literature. Economic Policy Review, 9(1), 7–26. https://ssrn.com/abstract=794804.

- Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2012). Information disclosure and corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 67(1), 195–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01710.x

- Huang, S., Lim, C. Y., & Ng, J. (2019). Not clawing the hand that feeds you: The case of co-opted boards and clawbacks. European Accounting Review, 28(1), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2018.1446036

- Humphery-Jenner, M., Liu, Y., Nanda, V. K., Silveri, S., & Sun, M. (2019). Of fogs and bogs: Does litigation risk make financial reports less readable? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3478994

- Hwang, B. H., & Kim, S. (2009). It pays to have friends. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(1), 138–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.07.005

- Jensen, M. C. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. The Journal of Finance, 48(3), 831–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb04022.x

- Kim, C., Wang, K., & Zhang, L. (2019). Readability of 10-K reports and stock price crash risk. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(2), 1184–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12452

- Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00059-9

- Knyazeva, A., Knyazeva, D., & Masulis, R. W. (2013). The supply of corporate directors and board independence. Review of Financial Studies, 26(6), 1561–1605. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hht020

- Lang, M., & Stice-Lawrence, L. (2015). Textual analysis and international financial reporting: Large sample evidence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(2-3), 110–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.09.002

- Lawrence, A. (2013). Individual investors and financial disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56(1), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2013.05.001

- Lee, Y. J. (2012). The effect of quarterly report readability on information efficiency of stock prices. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(4), 1137–1170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01152.x

- Lehavy, R., Li, F., & Merkley, K. (2011). The effect of annual report readability on analyst following and the properties of their earnings forecasts. The Accounting Review, 86(3), 1087–1115. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.00000043

- Levitt, S. D., & Snyder, C. M. (1997). Is no news Bad news? Information transmission and the role of ‘early warning’ in the principal-agent model. The RAND Journal of Economics, 28(4), 641–661. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555780

- Li, F. (2008). Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2-3), 221–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.02.003

- Lo, K., Ramos, F., & Rogo, R. (2017). Earnings management and annual report readability. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2016.09.002

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2011). When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. The Journal of Finance, 66(1), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2014). Measuring readability in financial disclosures. The Journal of Finance, 69(4), 1643–1671. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12162

- Loughran, T., McDonald, B., & Yun, H. (2009). A wolf in sheep’s clothing: The use of ethics-related terms in 10-K reports. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(S1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9910-1

- Miller, B. P. (2010). The effects of reporting complexity on small and large investor trading. The Accounting Review, 85(6), 2107–2143. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.00000001

- Nguyen, J. H. (2021). Tax avoidance and financial statement readability. European Accounting Review, 30(5), 1043–1066. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2020.1811745

- Rahman, D., Kabir, M., Ali, M. J., & Oliver, B. (2023). Does product market competition influence annual report readability? Accounting and Business Research, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2023.2165031

- Upadhyay, A., & Sriram, R. (2011). Board size, corporate information environment and cost of capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 38(9-10), 1238–1261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2011.02260.x

- Zhang, J. Z., & Yu, Y. (2016). Does board independence affect audit fees? Evidence from recent regulatory reforms. European Accounting Review, 25(4), 793–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2015.1117007