?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Employing firm-level work from home (WFH) suitability derived from the U.S. universe job postings, we investigate whether rating agencies and debt holders incorporate WFH suitability in their risk assessments. We document that firms with higher WFH suitability have higher credit ratings and lower costs of debt. Our results are robust to different fixed effect estimations, sampling methods, and controls. We identify two ways that WFH suitability translates into higher credit ratings: high WFH suitability is associated with lower future cash flow volatility and lower default risk. Overall, our study suggests that WFH suitability is an important determinant of credit risk assessments and that firms should see flexible work arrangements as an effective strategy in their crisis management planning.

Keywords:

‘The unprecedented pandemic is truly testing normal business risk management approaches right now.’ –

– Chris Donohue, Managing Director of the Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP) Benchmarking Initiative.

1. Introduction

Working-from-home (WFH hereafter) is a form of telecommuting that is robust to physical distancing (Fitzer, Citation1997). WFH essentially relies on technologies and organizational structures that allow employees to conduct jobs without human interaction in physical proximity. While WFH has become an increasingly common practice in recent times (Gallup, Citation2020), WFH is arguably most critical to firms during economic watersheds and disruptions. When a firm adopts WFH quickly and effectively, ensuring continued productivity and communication with its stakeholders, the firm can mitigate the adverse effect of events like COVID-19 on operations. However, firms vary greatly in their adaptability of WFH, resulting in observable heterogeneous resilience when firms have to handle unexpected disruptions to social and economic activities. In this study, we investigate whether credit assessments reflect the extent to which a firm is well suited to adopt WFH, also known as WFH suitability (Bai et al., Citation2020; Dingel & Neiman, Citation2020).

We rely on measures recently introduced in labor economics by Bai et al. (Citation2020) and Dingel and Neiman (Citation2020) that quantify the extent to which a firm’s operations are suitable with physical distancing. This index captures the percentage of a firm’s workforce that has the WFH option where higher values of the index indicate higher levels of WFH suitability. Bai et al. (Citation2020) first obtain universe job posting data from Burning Glass Technologies (BGT) and aggregate this data to the employer level. They then merge this BGT data with the WFH suitability data from Dingel and Neiman (Citation2020). This procedure enables these researchers to construct the percentage of incoming workers that is likely to have a WFH option for each firm. Using the COVID-19 outbreak as an exogenous shock, Bai et al. (Citation2020) document that firms with high WFH suitability exhibit higher stock returns and better financial performance.

We begin by validating that WFH suitability in Bai et al. (Citation2020) is a reasonable proxy for telework. First, we document that firms from metropolitan areas or from industries with the highest share of jobs that can be done from home exhibit higher WFH suitability. Second, high-tech firms and firms with global operations also exhibit higher WFH suitability. By contrast, those firms with high labor intensity or high proportion of routine-task labor show lower WFH suitability. The inclusion of several firm characteristics, industry and year fixed effects, can explain between 32-35% variation in firm-level WFH suitability. Thus, besides systematic variation, firms also exhibit a large degree of idiosyncrasies in their WFH suitability. Finally, we argue that the overall WFH suitability should go up after the outbreak of COVID-19 as firms adapt to the rolling lockdown and social distancing. We document evidence consistent with this conjecture. Specifically, we document a significantly higher level of WFH suitability in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the fourth quarter of 2019.

Following these validation tests, we turn our attention to examining whether WFH suitability is associated with credit risk assessments. We focus on a firm’s credit risk as this is one of the most important concerns in financing decisions, according to a seminal survey among top executives conducted by Graham and Harvey (Citation2001). The value of a firm’s creditworthiness is also highlighted during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998, the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, and most recently, the COVID-19 crisis starting in early 2020. In the extant literature, empirical studies such as Cornaggia et al. (Citation2017), Bonsall et al. (Citation2019), and Pham et al. (Citation2022) have explored how attributes of firm management may help explain the variation in credit risk assessment. In this study, we show that firms with higher WFH suitability enjoy higher credit ratings and lower corporate bond yield spreads. The results suggest that rating agencies and debt holders incorporate firm-level WFH suitability in their risk assessments.

One of the challenges in documenting the effects of WFH suitability is that WFH suitability may merely capture firm attributes that plausibly relate to the resiliency of operations. For example, firms in high-tech industries often exhibit higher levels of WFH suitability and these firms should be able to weather adverse shocks better than other firms because of their technology diversity, higher resourcefulness, and flexibility (see, for example, Hsu et al., Citation2018; Koren & Tenreyro, Citation2013). As such, we use several identification strategies to ensure that the results documented in our study are not driven by firm fundamentals or other omitted correlated variable bias.

First, we control for firm-fixed effects to account for possible time-invariant firm-specific omitted variables. If firm fundamentals, corporate organizational structures, and time-invariant firm characteristics such as culture or governance are those that chiefly drive credit ratings, the incorporation of firm fixed effects should allow one to find out whether WFH suitability is an incremental credit rating factor. We find the inclusion of firm fixed effects does not eliminate the role of WFH suitability. Second, we employ a propensity score-matched sample and show that firms with high WFH suitability exhibit better credit ratings than matched firms with low WFH suitability.

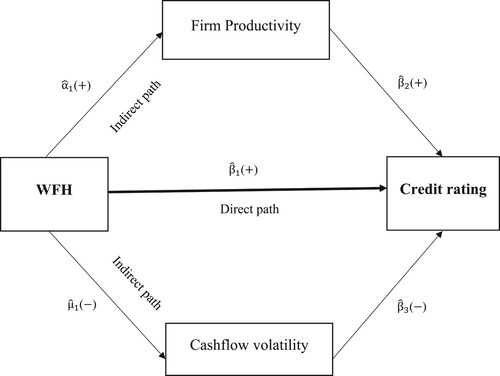

Third, we examine possible mechanisms through which WFH arrangements may influence credit risk. This analysis also shows fundamental channels that can help mitigate any possible spurious estimation. As workplace flexibility contributes to ensure business continuity and productivity in disruptions, we test two possible explanations that are central to credit risk assessments: i) lower future cashflow volatility, and ii) lower default risk. We find that firms with high WFH suitability are associated with a lower future cash flow volatility and a lower level of default risk. Notably, using path analysis, we find that WFH suitability has a direct impact on credit ratings, incremental to those readily captured by existing credit rating determinants.Footnote1

Forth, we explore the possibility that WFH suitability matters more for certain types of firms operating within certain economic environments than for other firms. We document that the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings is more pronounced among firms operating in a highly uncertain environment, firms with speculate-grade ratings of debts, firms in highly competitive markets, and firms belonging to non-high-tech industries. Thus, WFH suitability is an important credit rating factor, specifically among firms for which creditors may face relatively high credit risks.Footnote2

Our study offers three important contributions to the literature. First, contemporary research has uncovered several key attributes that help firms withstand the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. These include access to liquidity (Acharya & Steffen, Citation2020), high cash holdings (Ramelli & Wagner, Citation2020), strong balance sheet (Ding et al., Citation2020), high environmental and social ratings (Albuquerque et al., Citation2020; Bae et al., Citation2021), managerial ability (Nguyen et al., Citation2023), financial flexibility (Fahlenbrach et al., Citation2021), and governments’ business support programs (Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Philippon, Citation2021; Ru et al., Citation2021). Our study demonstrates WFH suitability as an important contributing factor to a firm’s resilient performance during a crisis episode. While the predominant view of telecommuting is cost saving and productivity improvement (Apgar, Citation1998; Pinsonneault & Boisvert, Citation2001), firms should also see WFH as an effective strategy in their crisis management planning.

Second, our study contributes to a nascent literature that evaluates WFH as a new dimension of future work. Given the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a prediction of a permanent switch to WFH as a new corporate norm (Brynjolfsson et al., Citation2020). Our study highlights that WFH suitability should become a key element of non-financial attributes, similar to other known metrics such as environmental, social, and governance performance (Albuquerque et al., Citation2020; Clarkson et al., Citation2019; Lins et al., Citation2017) or employee and customer satisfaction (Edmans, Citation2011; Truong et al., Citation2021). While our evidence suggests that rating agencies and debt capital providers factor flexible work arrangements such as WFH suitability in their risk assessments, WFH suitability can also be relevant to other stakeholders’ decisions such as investors’ portfolio choices, banks’ lending policies, auditors’ professional engagement, and policymakers’ guideline and standard formulation.

Finally, this study emphasizes the significance of information about firms, especially in the context that WFH suitability signals resilience that is relevant to lenders. Carruthers and Cohen (Citation2010) and Liberti and Petersen (Citation2019) establish that credit agencies can derive soft information from firms and then incorporate both soft and hard information in their credit rating decisions.Footnote3 Subsequent studies have attempted to examine how rating agencies incorporate various soft information in their credit risk assessment, such as managerial ability (Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017), managers’ experience and educational background (Ma et al., Citation2021; Pham et al., Citation2022), partisan perception (Kempf & Tsoutsoura, Citation2021), or corporate social responsibility (Attig et al., Citation2013; Chintrakarn et al., Citation2020; Jiraporn et al., Citation2014). A recent risk practice report by McKinsey & Company (Citation2020) also highlights the growing importance of soft information in that the conventional sources of data in credit risk assessments become obsolete in times of the COVID-19 pandemic and dynamic approaches to credit risk should incorporate digital transformation and high-frequency data into decision engine. While levels of WFH suitability may be observable to credit agencies in their assessments of firms’ operations, this information is rather difficult to summarize in a numeric value and likely requires a certain knowledge of context to fully comprehend. Thus, findings in our study can be viewed as evidence that soft information such as WFH suitability is reflected in credit agencies’ assessments. Our paper, therefore, contributes to a growing body of research that documents the relevance of soft information in credit risk assessments (e.g., see Pham et al. (Citation2022) for a review of the literature). In doing so, we also respond to Hanlon et al. (Citation2022)’s call for research that provides more insights into the behavioral economics of accounting for decision-makers.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses the related literature and empirical predictions. Section 3 discusses data and summary statistics. Section 4 presents empirical findings and Section 5 offers concluding remarks.

2. Related Literature and Empirical Predictions

Work from home (also called telecommuting or telework) is an alternative work method where employees can take advantage of advancements in technology and organizational structure to conduct work without the requirement of human interaction in physical proximity.Footnote4 This type of modern work arrangement has been increasingly common practice in recent times. In the United States, the proportion of employees who primarily work from home had more than tripled from 0.75% to 2.4% over the period 1980–2010 (Mateyka et al., Citation2012). This proportion stands at an all-time high of 65% in March 2020 due to the lockdown and social distancing in fighting the COVID-19 outbreak (Gallup, Citation2020).

The efficacy of WFH has been an important topic in the research literature as well as in practice. Based on several case studies and surveys, earlier studies (Bailyn, Citation1988; Bélanger, Citation1999; DuBrin, Citation1991; Mokhtarian, Citation1991; Nilles, Citation1975; Olson, Citation1988; Piskurich, Citation1996) have documented positive associations of WFH adoption with lower employee turnover and absenteeism and with higher productivity and profitability. These positive impacts on productivity and employees can be mainly attributed to the higher degree of autonomy when employees work at home and thus they have higher intrinsic motivation. However, a major drawback of these research findings is that employees may self-select into their WFH arrangement, thereby potentially upwards biasing productivity outcomes.

To address the self-selection problem of working from home, recent studies rely on experimental research designs (Bloom et al., Citation2015; Dutcher, Citation2012). Using a laboratory experiment where students from a U.S. university conduct tasks that mimic real work, Dutcher (Citation2012) finds that working from home increases productivity when individuals perform creative tasks but decreases productivity when individuals perform repetitive tasks. Bloom et al. (Citation2015) conduct a randomized corporate experiment in a large Chinese travel agency and report significant productivity gains from telework. This productivity improvement comes about mainly because WFH arrangement enables flexibility, convenience, and a quiet working atmosphere.Footnote5

There has been little empirical research of large scale on the impact of WFH on firm performance, mostly due to a lack of data on firm-level variation in WFH practices. The study of Bai et al. (Citation2020) employs the universe of U.S. job postings to construct a firm-level index of WFH suitability and is the first that offers assessments of the cross-sectional variation in the extent to which each firm’s work is suitable for work from home. Using a difference-in-differences framework, the study then documents evidence that firms with high WFH index values, compared to their low-WFH peers, have higher stock returns and better financial performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bai et al. (Citation2020) conclude that WFH suitability acts as a resilience factor that helps firms cope with major adverse social and economic shocks.

We conjecture that high values of WFH suitability are also relevant to the debt market in that there is a lower likelihood that firms with high WFH suitability miss principal and interest payments. This is because when social distancing or lockdown is required during adverse economic conditions, a smooth and prompt switch to WFH allows firms to maintain productivity and continuous communication with their stakeholders. Essentially, those firms with high levels of WFH suitability should be able to avoid operational disruptions. Correspondingly, the value of WFH suitability is likely to reduce the collection uncertainty of firms’ debt, which should manifest through higher levels of credit rating.Footnote6

We also acknowledge that as a priori, it may not be exactly clear that the impact of WFH suitability on credit ratings will necessarily be incremental to those from firm fundamentals. First, prior research suggests that most of the variation in credit ratings can be explained by firm fundamental factors and thus differences in WFH suitability may not play a large role in the rating process. Second, research results in Bai et al. (Citation2020) showing the benefits of WFH suitability to equity holders may not necessarily translate to the debt market, as debt and equity holders often have different tolerances and preferences for risk.Footnote7 Finally, if the cross-sectional variation in WFH suitability merely reflects an array of known firm characteristics and industry norms, one should expect little value from a synthetic dimension.Footnote8

Given mixed implications from extant literature, the relation between WFH suitability and credit risk remains an open and important empirical question. In this study, we address this question via a four-pronged research investigation. First, we assess the construct validity of a firm-specific measure of WFH suitability. We relate WFH suitability values to observable determinants of WFH suitability and the COVID-19 shock. Second, we examine the relation between WFH suitability and several measures of firms’ performance that should be relevant to debt holders. Third, we examine the impact of WFH suitability on credit ratings and bond yield spreads. Finally, using a difference-in-differences framework, we study the impact of WFH suitability on a firm’s distance to default during the COVID-19 pandemic period to estimate causal effects.

3. Data and Summary Statistics

3.1. Data and Sample

We obtain firm-specific accounting data and credit ratings from Compustat, stock prices and returns from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), and corporate bond data from Mergent Fixed Income Securities Database. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Cheng & Subramanyam, Citation2008), we exclude financial and utility firms from our sample and winsorize all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The other data we use include analyst coverage data from the I/B/E/S database, institutional ownership information from Thomson Reuters Institutional Holdings (13F) database, corporate social responsibility rating information from the MSCI/ KLD database, and board quality data from the ISS/ RiskMetrics database.

Our sample for validation of firm-level WFH suitability consists of 11,947 firm-year observations spanning 2010–2019. Our final credit rating sample consists of 6,237 firm-year observations spanning 2010–2020.Footnote9 Appendix A provides a detailed description of the variables used in this study.

3.2. Measures of Credit Rating

Following credit risk assessment literature (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., Citation2006; Kim et al., Citation2013), we obtain Standard & Poor’s Long-term Domestic Issuer Credit Rating from Compustat and Capital IQ databases and construct numeric variables that reflect the ratings of the issuers.Footnote10 Specifically, we translate ratings numerically, increasing in credit quality as follows: D (or SD) = 1, … , AAA = 22.Footnote11 We follow Ham and Koharki (Citation2016) and Pham et al. (Citation2022) and use the average of a firm’s monthly credit ratings in a given fiscal year, denoted RATING, as our measure of credit rating.

We also consider two alternative measures of credit ratings. First, we use credit ratings from Egan-Jones Ratings Company, an investor-paid rating agency (e.g., Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2022; Xia, Citation2014). Second, we employ issuer-level ratings from Mergent Fixed Income Security Database (FISD) as an alternative measure of credit risk.Footnote12

3.3. Measures of Working from Home Suitability

Bai et al. (Citation2020) construct a firm-level measure of the percentage of the workforce that has the work-from-home option by matching over 200 million job postings from the Burning Glass Technologies database with the working-from-home suitability indication from Dingel and Neiman (Citation2002).Footnote13 We use the average of a firm’s quarterly working-from-home suitability scores in a given year as our measure of working from home suitability (denoted WFH). The higher value of WFH scores indicates higher levels of work from home suitability.

We also construct the firm-level working from home suitability score that is industry-adjusted and therefore comparable among firms across industries. Specifically, for each year and in each industry, we compute the mean of WFH scores within each industry and use the difference between each firm WFH score and the industry average value as the industry-adjusted WFH score (denoted WFH_IND_ADJ).

In addition, we employ a dichotomous variable for high levels of WFH suitability. Specifically, HIGHWFH is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s WFH suitability scores fall into the top quintile of the sample distribution and zero otherwise.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

We present the descriptive statistics for variables employed in the study in Panel A and the correlation matrix among these variables in Panel B of .

Table 1. Summary statistics for credit rating sample.

The average WFH score is 0.588 with a standard deviation of 0.251, which indicates a considerable amount of variation in the cross-section. The average credit rating is 12.501 (corresponding to the medium ratings, BBB-). The average firm size (in logarithm form) is 8.83 and the average debt-to-asset ratio is 36%. On average, firms earn 4.60 percent return-on-asset (ROA) and cover their interest 14 times. The average book-to-market ratio is 0.421 and the average cash flow volatility (CFVOL) is 0.028. In our sample, 14.3 percent of firm-year observations are associated with negative earnings. Overall, our credit rating and firm characteristics are in line with prior studies (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., Citation2006; Cheng & Subramanyam, Citation2008; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2022).

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. Validation of WFH Suitability

We start our empirical analysis by assessing the validity of our firm-level WFH suitability measure. We consider two validation analyses.

First, we examine whether our firm-level WFH suitability measure is related to a set of firm attributes plausibly correlated with telework or work from home. We consider a range of possible determinants of work-from-home options, including (i) firm size (LOGSIZE), (ii) debt-to-asset ratio (LEV) ratio as a proxy for the debt-related pressures faced by the firm (iii) return-on-assets (ROA), return volatility (REVOL) as a measure of operating risk (Callen et al., Citation2010), (iv) inventory-to-sale ratio (INVENTORY), book-to-market ratio (BTM) to capture expected growth prospects, (v) an indicator indicating where a firm’s foreign sale ratio is above the sample median (FSALES), (vi) an indicator indicating where a firm belongs to high tech industries (HIGHTECH) following National Science Foundation (Citation1998), (vii) the industry-level share of jobs (IND_TELE) that can be done from home from Dingel and Neiman (Citation2020), (viii) an indicator, METRO_TELE, indicating top 5 metropolitan areas with the highest share of jobs that can be done at home from Dingel and Neiman (Citation2020), (ix) labor intensity (LABOR_INTENSITY) defined as the proportion of the number of employees over total sales, and (x) a firm’s share of routine-task labor (ROUTINE) from Zhang (Citation2019). We report the correlation matrix between WFH suitability and firm determinants in Appendix OA13 in the Online Appendix and regression results in Table 2’s Panel A.

We find that WFH suitability is positively related to (i) metropolitan areas with the highest share of jobs that can be done from home and (ii) industries with the highest share of jobs that can be done from home, (iii) foreign sales, (iv) high tech firms and negatively related to (v) firms with a high proportion of routine-task labor and (vi) firms with high labor intensity. These findings suggest that WFH suitability correlates well with attributes that should facilitate a high level of WFH.

Second, we use the COVID-19 pandemic as an exogenous shock on work-from-home and consider WFH suitability before and during Covid-19. Figure A1 in the Online Appendix shows that the is a significant increase in Google search for ‘work from home’ in 2020. Figure A2 in the Online Appendix shows that over the period January-June 2020, ‘work from home’ is mentioned in the media more than 10 times higher than in the whole year of 2019. These findings confirm our expectation that the practice of WFH should be particularly higher in 2020. Results from Panel B of suggest that the firm-level WFH suitability scores are indeed significantly higher during the Covid-19 period compared to the pre-Covid19 period. On average, firms show a 1.5% gain in the percentage of work that can be done from home in the first quarter of 2020.

Table 2. Validation of firm-level WFH suitability.

Overall, the evidence from our examination of cross-sectional variation in WFH suitability and the change surrounding the Covid-19 shock suggests that WFH suitability correlates with WFH-enabling attributes, and this score also rises noticeably once the pandemic starts. Interestingly, our models with a comprehensive list of firm characteristics and industry norms explain about 32% to 35% of the variation in WFH suitability. Thus, while WFH can be systematically determined, a large extent of variation in WFH suitability appears to be firm-level idiosyncrasies. This is in line with the survey finding from Bloom et al. (Citation2009) on varying practices of WFH across firms.

We continue our analyses by considering the impacts of WFH suitability on corporate outcomes that matter for the overall risk profile of a firm. Specifically, we investigate how WFH suitability affects a firm’s overall productivity and its future variability. Our focus on these corporate outcomes is intuitive, for three reasons. First, WFH suitability is part of a disaster recovery and business continuity plan which helps firms quickly recover and better respond to operational disruption. For example, a crisis such as the recent pandemic may force employees to work from home, creating disruption in the workforce. The extent to which firms can smoothly facilitate this transition (better WFH suitability) will influence overall workforce productivity. Second, WFH suitability should enable flexibility, autonomy, and a convenient working atmosphere (Bloom et al., Citation2015; Dutcher, Citation2012; Rupietta & Beckmann, Citation2018). As human capital is the key driver of corporate total outputs we expect that employees with WFH arrangement options would experience more satisfying working conditions, higher intrinsic motivation and job dedication, and deliver higher productivity.Footnote14 In addition, having a flexible work arrangement could also influence retention rates, leading to lower levels of voluntary turnover, and reducing the costly and time-consuming re-hiring and training expenditures. Third and finally, WFH flexible arrangements can facilitate business continuity by maintaining sufficient operating cash flows and reducing the uncertainty of future outcomes, especially during major disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Nguyen et al. (Citation2021)).Footnote15 We, therefore, consider both the short-term and long-term effects of WFH suitability on these corporate outcomes.

Appendix A1 reports the results for these tests. We find that firms with higher WFH suitability exhibit lower cash flow volatility and higher productivity compared to their peers. In addition, the impacts of WFH on a firm’s productivity and its future variability tend to be short or medium rather than long-term.

4.2. The Effect of Work-from-home Suitability on Credit Ratings

4.2.1. Univariate analysis

We follow the accounting literature and use credit rating as a primary indicator of a firm’s credit risk (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., Citation2006; Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Cheng & Subramanyam, Citation2008; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2013; Kuang & Qin, Citation2013). According to Standard & Poor’s, a firm’s credit rating reflects a ratings agency’s opinion of the entity’s overall creditworthiness in terms of its capacity to satisfy its financial obligations (Standard and Poor’s, Citation2002). We examine whether, and to what extent, rating agencies incorporate firm-level WFH suitability into their risk assessment. We start our univariate analysis by forming portfolios based on firms’ working-from-home suitability scores. In each year t, we sort stocks into decile portfolios based on their WFH (WFH_IND_ADJ) scores and then compute the portfolio credit rating by taking the average of the ratings across all stocks in the portfolio.

reports the descriptive statistics for the rating across WFH-sorted portfolios. Firms in the high WFH suitability portfolios have higher credit ratings. The 10–1 row reports the average rating difference between the low and high WFH suitability stock. These univariate results establish a positive relation between WFH suitability and credit rating at the univariate level. However, some of the differences in credit risk could be due to other firm characteristics which we will consider in the following sections.

Table 3. The effect of work-from-home suitability on credit ratings: Univariate analysis.

4.2.2. Regression analysis

We employ a regression framework where we can control for firm-specific characteristics and time-invariant factors at the same time. We use the following regression:

(1)

(1)

where RATING is the S&P issuer credit rating; HIGHWFH is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s working from home suitability scores falls into the top quintile of the sample distribution and zero otherwise; Controls refer to firm-level control variables, and FixedEffects refer to industry-fixed effects (firm-fixed effects) and year fixed effects. Following prior studies (e.g., Kaplan & Urwitz, Citation1979; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., Citation2006; Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2022), we control for various firm characteristics that can be associated with firm credit risk assessment, including firm size (LOGSIZE), debt-to-asset ratio (LEVERAGE), return-on-assets (ROA), interest coverage (INT_COV), an indicator of whether the firms report negative earnings in a prior fiscal year (LOSS), financial distress measured by Altman (Citation1968)’s z-score (ZSCORE), firms’ capital intensity (CAP_INTEN), an indicator indicating if the firm has subordinated debt (SUBORD). We further control for the book-to-market ratio (BTM) and the volatility of a firm’s operating cash flow (CFVOL) to capture expected growth prospects and the cash flow volatility (e.g., Cheng & Subramanyam, Citation2008; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017). We also include a contemporaneous stock return to capture expected business disruptions. We use the cumulative monthly returns in a given year (CUMRET). Finally, we control for year fixed effects and industry fixed effects (based on Fama-French 48 industry classifications) to control for time- and industry-invariant factors that could be associated with credit ratings.

We also control for firm fixed effects to account for time-invariant firm-specific omitted variables. Following credit rating literature (e.g., Cornaggia et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2013; Kuang & Qin, Citation2013), we use concurrent independent variables to minimize the possibility that prior years’ WFH suitability results in observables in the current year, which are then incorporated in the current year’s ratings. To correct for cross-sectional and time-series dependence, we use robust standard errors clustered simultaneously by firm and year dimensions (Petersen, Citation2009; Gow et al., Citation2010).Footnote16

For regression analysis, we consider both the OLS estimation and the ordered logit models. The OLS estimation requires that the distance between two adjacent rating categories be constant across the full range of ratings, whereas, the ordered probit estimation can accommodate the varying distance between adjacent rating categories, but is more sensitive to a large number of fixed effects. We, therefore, report the results from the ordered probit model to complement the OLS results.

presents the baseline regression results. We find that the coefficient estimates on work-from-home suitability are positive and significant across different model specifications. This suggests firms with higher WFH suitability have more favorable credit ratings. In model (1), firms in the top quintile of the WFH suitability scores (i.e., HIGHWFH = 1) exhibit 0.38 higher in credit rating. In model (2) when firm fixed effects are employed, the economic magnitude becomes smaller, with firms in the top quintile of the WFH suitability scores (i.e., HIGHWFH = 1) exhibiting 0.102 higher in credit rating.

Table 4. The effect of work-from-home suitability on credit ratings: Regression analysis.

Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., Citation2006; Cornaggia et al., Citation2017; Kaplan & Urwitz, Citation1979; Kuang & Qin, Citation2013), credit risk assessment is more favorable for larger firms, firms with higher return-on-asset ratio, firms with higher expected growth prospects and lower financial distress while lower for firms with higher leverage, firms that report a loss in the prior fiscal year, firms with subordinated debts, and firms with higher cash flow volatility.

In Online Appendix, we supplement the baseline regression results in with a myriad of robustness tests to ensure that our results are not sensitive to specific model specifications, alternative measures of WFH suitability, an alternative measure of default risk, or additional control variables. We report the results for these tests in Appendix OA2 in the Online Appendix. We find our results are robust. In Appendix OA3, we employ credit ratings from Egan-Jones Ratings Company as an alternative measure of credit risk. Prior studies (e.g., Beaver et al., Citation2006; Xia, Citation2014) suggest that investor-paid rating agencies, such as Egan-Jones Ratings, can produce more informative ratings than issuer-paid rating agencies, and hence can be employed as an independent assessment of credit risk. We also employ issuer-level ratings from Mergent Fixed Income Security Database (FISD) as another measure of credit risk and report the results for this test in Appendix OA7. Consistent with the previous analyses, the samples for two alternative measures of credit risk (i.e., Egan-Jones ratings and issuer-level ratings) begin in 2010 (as it is the first year the WFH suitability data is available) and end in 2020, the latest available data at the time of writing this paper. Results from Appendix OA3 and Appendix OA7 consistently suggest that WFH suitability is associated with better credit risk assessment. In Appendix OA4, we consider several alternative explanations and find that WFH suitability has an effect on credit risk assessments that is independent of corporate governance and other monitoring mechanisms such as financial analysts, institutional investors, or board quality. Furthermore, we use the proportion of WFH suitability that cannot be explained by firm fundamentals in Appendix OA6 and further confirm that WFH suitability is important, incremental to firm fundamentals, in credit rating assessments.

4.2.3. Propensity-score-matched sample analysis

A potential concern of the relation between WFH suitability and credit risk assessment is that firms with and without WFH suitability options could be fundamentally different. Thus, the association between WFH suitability and credit ratings could be driven by differences in firm characteristics. To ensure that we compare the credit ratings of firms with higher WFH suitability and the credit ratings of otherwise similar firms, we use the propensity score matching approach.

We first estimate the probability of being assigned to the treatment or control group using a logistic regression with all firm-level controls as specified in the baseline regression (equation Equation(2)(2)

(2) ) and firms within the same industry. Our treatment (control) group includes firms with (without) WFH suitability scores that fall into the top quintile of the sample distribution. We then use propensity scores to perform one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching within 0.01 caliper without replacement. We report the average treatment effect estimates in panel A of . ’s results suggest that treated firms and their matched control firms have similar characteristics. This confirms the high quality of the match. More importantly, we find that credit ratings are higher for firms in the treatment group relative to firms in the control group.

Table 5. Propensity-score-matched sample analysis.

We then take a more conservative step and further perform a regression analysis based on the matched sample to mitigate any differences that can be attributed to firm fundamentals. If WFH suitability scores matter for the credit risk assessment, we would expect the significant effect of WFH arrangement on credit ratings in a matched sample once all firm attributes, time- and industry-invariant factors, that could be associated with credit ratings, are taken into consideration. We include the results for these analyses in Panel B of .

Model (1) and Model (2) report the results for OLS models and ordered logit models, respectively. We find that the effect of WFH suitability on credit ratings based on a matched sample is both statistically and economically similar to that in our baseline models in . These findings suggest that firms with higher WFH suitability have more favorable credit ratings and that this effect is not entirely driven by firm fundamentals.Footnote17

4.2.4. Possible channels

Having documented the relation between WFH suitability and credit rating, we next turn our attention to mechanisms that could underlie this relation. We conjecture that there are two possible channels through which WFH suitability influences credit risks.

First, workplace flexibility contributes to maintain business continuity and productivity in disruptions, leading to sustainable performance and lower risks of default. As a result, the first possible channel through which WFH suitability can influence credit rating is through sustaining firm productivity.

Second, WFH flexible arrangements can facilitate business growth by maintaining sufficient workout personnel and operating cash flows, hence reducing the variability of future outcomes (e.g., Giurge and Bohns, Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2021).Footnote18 Workplace flexibility also contributes to lower levels of employee voluntary turnover, reducing abnormal expenditures in re-hiring, training, or other labor costs. Appendix A1 provides strong evidence for this conjecture. Given credit rating agencies consider the volatility of future cash flows when assessing firms’ repayment capability (Standard and Poor, Citation2002), reducing cash flows variability is another possible mechanism that WFH can promote a firm’s capacity to service its future debt obligations, and hence contribute to its overall creditworthiness.

To test for these possible channels, we follow the accounting literature (e.g., DeFond et al., Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2022) and adopt a path analysis. Path analysis uses a structural equation model to test how a source variable (in our setting, WFH suitability) affects an outcome variable (here, credit rating) by decomposing the correlation between the source and the outcome variables into their direct and indirect paths through mediating variable(s) (e.g., Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). Path analyses in our study serve two meaningful purposes. First, we would verify whether the documented relationship between WFH suitability and credit rating is spurious given a statistically significant relation neither immediately implies causation nor an economic fundamental underlying the relation (Wooldridge, Citation2016). Second, this path analysis would help quantify the magnitude of the direct and indirect paths from WFH suitability to credit ratings.

We use the volatility of future cash flows (denoted CFVOL) to capture future variability. To capture firm productivity, we employ the firm-level total factor productivity measure (denoted TFP) as proposed in İmrohoroğlu and Tüzel (Citation2014). We perform the following models for our path analysis:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

The independent variable of interest is WFH suitability. Rating is the S&P issuer credit rating as discussed in Model (1). TFP and Cashflow Volatility capture firm productivity and the volatility of future cash flows, respectively. Controls include relevant control variables from the baseline regression in Model (2). The path coefficient β1 is the magnitude of the direct path from WFH suitability to credit ratings. The path coefficient β2 (β3) is the magnitude of the path from firm productivity (cashflow volatility) to credit ratings. The path coefficient is the magnitude of the indirect path from WFH to credit rating mediated through firm productivity (cashflow volatility). Figure 1 graphically illustrates the direct and indirect paths and reports the results for this path analysis.Footnote19

Table 6. Path analysis.

According to ’s results, the direct path coefficient between WFH and credit rating [P(WFH, Credit Rating)] is positive and significant at the 1% level, confirming our baseline result that firms with higher WFH suitability are associated with higher credit ratings. Regarding the first mediating variable, firm productivity, the path coefficient between WFH and firm productivity [P(WFH, Path)] is positive and significant at the 1% level (the coefficient estimate of 0.2020 and p-value < 0.01), suggesting that firms with higher WFH suitability are associated with higher productivity. Similarly, the path coefficient between WFH and cashflow volatility [P(WFH, Path)] is negative and significant at the 1% level (the coefficient estimate of −0.0765 and p-value < 0.01), suggesting that firms with higher WFH suitability are associated with lower cash flow volatility.

The path coefficients between firm productivity and credit ratings and between cashflow volatility and credit ratings [P(Path, Credit Rating)] are all significant at the 1% level. This is consistent with our conjecture that higher firm productivity and lower cashflow volatility lead to higher credit ratings. The total mediated path for firm productivity, , is positive and significant at 1% with a coefficient estimate of 0.0175 and p-value < 0.01. The result implies that firm productivity is a significant channel that helps explain 30.97% [ = 0.0175/ (0.0390 + 0.0175)] of the positive relation between WFH suitability and credit rating. Similarly, cashflow volatility is a significant channel that helps explain 6.37% [ = 0.0027/ (0.0390 + 0.0027)] of the positive relation between WFH suitability and credit ratings.

Overall, the path analysis in suggests two main findings. First, the effect of WFH suitability on credit rating is significantly mediated through at least two channels: (i) firm productivity and (ii) cashflow volatility. Second, WFH suitability has a direct impact on credit ratings, incremental to those readily captured by existing credit rating determinants.

4.2.6. Cross-sectional analysis

We explore the possibility that WFH suitability matters more for certain types of firms within certain economic environments than for others. Specifically, we examine the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings separately for (i) firms with higher and lower levels of past variability, (ii) investment- and speculative-grade firms, (iii) firms in highly competitive markets, and (iv) firms belong to high-tech and other industries.

First, we examine the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings conditional on environment uncertainty, measured by the volatility of cash flows during the previous four years. Second, we consider firms with investment-grade ratings (ratings better than or equal to BBB-) and firms with speculative-grade ratings (S&P ratings below BBB-). Third, we examine the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings conditional on the competitive environment. Workplace flexibility is important to retain talents, especially in highly competitive markets (e.g., Rupietta & Beckmann, Citation2018). Market competition is, therefore, related to flexible work arrangements. To measure product market power, we construct a Lerner index (Lerner, Citation1934), with higher values of the index indicating higher product market competition. Finally, we examine the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings for firms belonging to high-tech industries and other industries. We follow Decker et al. (Citation2017) and define high-tech industries using their 4-digit NAICS codes. We use the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) and the Wald test for the coefficient differences across different subsamples (e.g., Bonsall et al., Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2022).

presents the results of these tests.Footnote20 We document that the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings is more pronounced among firms operating in a highly uncertain environment, firms with speculate-grade ratings, firms in highly competitive markets, and firms belonging to non-high-tech industries. Overall, WFH suitability is an important credit rating factor, specifically among firms for which creditors face relatively high credit risks.

Table 7. Cross-sectional analysis.

4.3. Work-from-home Suitability and Bond Yield Spread

We use the cost of debt capital as a proxy for the market-based measure of a firm’s credit risk and examine whether a firm’s WFH suitability affects bond investors’ required rates of return. We consider all new nonconvertible issue fixed-rate corporate bonds issued, reported by the Mergent Fixed Income Security Database (FISD), and then match the FISD data with Compustat and CRSP data, yielding a final sample of 1,501 firm bond issuances during our sample period. Offering credit spreads are measured as the offering yields to maturity in excess of similar duration treasuries. We employ the following regression:

(5)

(5)

where LnSPREAD is offering credit spread in logarithm form, WFH refers to two measures of working from home suitability scores; ISSUE refers to issue issuance-specific characteristics; Controls refers to firm-level control variable, and IndFE (YearFE) refers to industry-fixed effects (year-fixed effects). We control for issuance-specific characteristics, including the natural logarithm of the offering amount of the new bond (LnOFFER) and the number of years until maturity on the new bond (MATURITY), and further control for various firm characteristics that can be related to credit quality as in the baseline regression in . In addition, we include bond issuance-specific rating fixed effects, year- and industry-fixed effects to control for bond issuance-specific ratings, and time- and industry-invariant factors that could be associated with bond spreads.

presents the results for these tests. We find the coefficient estimates on WFH and WFH_IND_ADJ are negative and significant across all model specifications, suggesting that firms with higher WFH suitability are associated with a lower credit spread. The magnitude of the WFH suitability effect on credit spreads is also economically significant. In model (2) of , moving from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile of WFH suitability results in a reduction in credit spread by 3.29% ( = −0.0875 × 0.376).

Table 8. Work-from-home suitability and bond yield spread.

4.4. The Impact of Covid-19 on Corporate Default Risk

To further address a potential identification challenge that firm-level WFH suitability is unlikely random, but rather a firm’s endogenous choice, we use the COVID-19 outbreak and enforced lockdowns as an exogenous shock to work-from-home and argue that firm-level WFH suitability before the COVID-19 is orthogonal to the pandemic.

Not surprisingly, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has forced millions of employees to work from home. Next, the pandemic-induced economic shock, together with the requirement for social distancing and lockdowns, should materially increase the expected corporate default frequency because of heightened cash flow risk. Whether firms would face operational disruptions then should largely depend on the suitability of their work for WFH during the pandemic. The capacity to switch to WFH arrangement allows firms to maintain their business operations and mitigate cash flow risk. Firms with this ability should be less sensitive to the pandemic and, compared to others, have lower default risk. This observation forms the basis for our empirical tests: we predict a lesser impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the default risk of firms with high WFH suitability.

Panel A of presents mean values in expected default frequency between 2019 (pre-COVID-19) and 2020 (COVID-19) for firms in our sample. We employ data in the last two quarters of 2019 and the first two quarters of 2020 for this analysis. The result is consistent with the COVID-19 pandemic having a tangible effect on expected default frequency. The expected default frequency is, on average, 0.05 in the last two quarters of 2019, and 0.07 in the first two quarters of 2020 (the difference is significant at the 1 percent level).Footnote21 This is a 37% increase, consistent with an exogenous rise in expected default frequency caused by COVID-19.

Table 9. The impact of COVID-19 on corporate default risk.

In order for a difference-in-differences regression to be an appropriate methodology, outcome variables for firms with high WFH suitability and other firms should exhibit parallel trends over the pre-COVID-19 period. TimeTrend is a time trend variable that captures four quarters in 2019. We use the following regression:

(6)

(6)

where EDF refers to two measures of default risk, including (i) the expected default frequency measure (EDF) proposed by Bharath and Shumway (Citation2008) and Brogaard et al. (Citation2017) and (ii) the industry-adjusted value (EDF_IND_ADJ); High_Suitability is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s average WFH suitability score during the pre-COVID-19 period (2010-2019) belongs to the top quartile of the sample distribution and zero otherwise; CTRL refers to firm-level control variables as in Brogaard et al. (Citation2017); and FEs refer to industry-fixed effects.

Panel B of presents a parallel trend test. The test variable is the interactive term, High_Suitability × TimeTrend, which is insignificantly different from zero. This trend test indicates that there is no pre-treatment difference in default risk between the two groups of firms and that the impact on default risk occurs after the COVID-19 outbreak.

We then estimate a difference-in-differences regression model to examine whether a firm’s WFH suitability prior to the COVID-19 pandemic influences its default risk. We use the following regression:

(7)

(7)

COVID19 is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for the first two quarters of 2020 and zero for the last two quarters of 2019. Firm controls include firm size, leverage ratio, book-to-market ratio, asset liquidity, the ratio of net income to total assets, the inverse of annualized stock return volatility, and annual excess returns (Brogaard et al., Citation2017).

The parameter of interest is the coefficient on the interaction term (High_Suitability × COVID19) which captures the differential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on firms with high versus low values of pre-COVID WFH suitability scores. We focus on a short window of two quarters before and during the Covid-19 pandemic to capture its immediate impact, and at the same time, mitigate the possibility of confounding effects from other corporate and market events. To correct for cross-sectional and time-series dependence, we use robust standard errors clustered simultaneously by both firm and quarter dimensions (Gow et al., Citation2010; Petersen, Citation2009).

We report the results for these tests in Panel C of . The coefficient estimates on the interaction term, High_Suitability × COVID19, are negative and statistically significant across different model specifications. Footnote22 This indicates that firms with high WFH suitability, when compared to their counterparts with low WFH suitability, exhibit lower expected default frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic. The magnitude of the WFH suitability effect on default probability is economically significant. In model (5) of ’s Panel C, the change in EDF of firms in the top quartile of pre-COVID-19 WFH suitability scores (i.e., High_Suitability = 1), compared to the change in EDF of other firms, is 1.90% lower in the first two quarters of 2020.

4.5. Firm-level Covid Exposure and Default Risk

As some firms can be more exposed to COVID-19 than others (Albuquerque et al., Citation2020; Ding et al., Citation2020; Hassan et al., Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2023), we examine the impact of WFH suitability on corporate default amid the pandemic conditioning on the levels of firms’ exposure to the pandemic. We employ a novel measure of firm-level exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic, captured by the frequency of keywords related to COVID-19 extracted from the earnings call transcripts developed by Hassan et al. (Citation2020).Footnote23 If a firm’s WFH practices prior to the COVID-19 pandemic indeed influence its credit risk during the pandemic, we expect this impact to be more pronounced for firms that are more exposed to the pandemic.

To test this possibility, we re-estimate a difference-in-differences regression model as in for two subsamples based on the firm-level exposures to the COVID-19 pandemic. We define high (low) COVID-exposure firms as those above (below) the sample mean of the COVID-19 risk exposure over the first two quarters of 2020. We report the results for these tests in .

Table 10. Work-from-home suitability, firm-level COVID exposure, and default risk.

’s results suggest that the effect of WFH suitability on default risk during the COVID-19 pandemic is more pronounced among firms that are more exposed to the pandemic. For example, in models (1) and (2) of , among high-COVID-19 exposed firms, the change in EDF of firms in the top quartile of pre-COVID-19 WFH suitability scores (i.e., High_Suitability = 1), compared to the change in EDF of other firms, is 2.60% (t-statistics of −2.35) lower in the first two quarters of 2020, whereas, this change in EDF among firms in low-incidence states is 1.24% (t-statistics of −1.43). We observe similar findings when industry-adjusted EDF measures are employed in models (3) and (4).

We then use the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) and the Wald test for the coefficient differences across different subsamples. Collectively, we find that compared to their counterparts with low WFH suitability, firms with high WFH suitability exhibit lower default risk during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the effect is stronger among firms that are more exposed to the pandemic.Footnote24

5. Conclusions

Our study investigates whether WFH suitability contributes to the resiliency of firms and if rating agencies and debtholders incorporate this flexibility of work arrangements in risk assessments. Using a novel dataset of U.S. job postings to capture an index of firm-level WFH suitability, we find that firms with high WFH suitability enjoy higher credit ratings and lower corporate bond yield spreads. These findings are robust in a battery of identification strategies. We find that firms with high WFH suitability are associated with lower future cash flow volatility and lower default risk, resulting in favorable credit ratings. In addition, the impact of WFH suitability on corporate credit ratings is more pronounced among firms operating in a highly uncertain environment, firms with speculate-grade ratings, firms in highly competitive markets, and firms belonging to non-high-tech industries.Footnote25

Our study has explicit research and policy implications. Research findings in this study suggest WFH suitability is an important contributing factor to resiliency, with the effect translating into a significantly lower cost of debt capital. Future research should investigate the exact mechanisms of how WFH suitability can curb downside risks. The accounting literature (Johnson et al., Citation2008; Kornberger et al., Citation2010) has also been long interested in how resources should be allocated to alternative work arrangements. Given that WFH is not just a temporary aberration but may become the ‘new normal’ workplace in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, research to uncover corporate policies that can facilitate the effective implementation of WFH is undoubtedly vital.Footnote26

Acknowledgments

We appreciate helpful comments from Chris Adrian, Jim Arrowsmith, John Bai, Jo Bensemann, Steven Cahan, Bevan Catley, Brian Connelly, Joe Cooper, Charles Corrado, Jonathan Doh, Huu Duong, Natalia D’Souza, Peter Easton, Gabriel Eweje, Mukesh Garg, Ahsan Habib, Jenny Hoang, Kaz Kobayashi, Conor O’Kane, Shane Moriarity, Hannah Nguyen, Cuong Nguyen, Beatriz Garcia Osma, Amy Pham, Nitha Palakshappa, David Pauleen, Richard Pucci, David Tappin, Aymen Sajjad, Brian Spisak, Minh Hanh Thai, Charl de Villiers, Duc Vu, Carla Wilkin, Suze Wilson, Ros Whiting, Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility Research Group at Massey University, and seminar participants at Monash University. Harvey and Cameron acknowledge financial supports from Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand Research Grant and Massey Strategic Excellent Fund. All remaining errors are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability

The data are available from the sources identified in the paper.

Supplemental Research Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, doi:10.1080/09638180.2023.2239865.

Appendix OA1: Work-from-home suitability and corporate outcomes.

Appendix OA2: Work-from-home suitability and credit ratings: Additional analysis.

Appendix OA3: Regression Analyses based on Egan-Jones Ratings.

Appendix OA4: Alternative explanations.

Appendix OA5: Instrumental Variable Analysis.

Appendix OA6: Work-from-home suitability and credit rating: Residual approach.

Appendix OA7: Work-from-home suitability and issuer-level rating.

Appendix OA8: Univariate analysis of expected default frequency in 2020.

Appendix OA9: The impact of COVID-19 on corporate default risk across states.

Appendix OA10: WFH suitability, employment & operation related violations during pandemic.

Appendix OA11: Correlation matrix between WFH suitability and firm determinants.

Figure A1: Google search on ‘work from home’.

Figure A2: Media mentions on ‘work from home’ from Factiva global news.

Figure A3: Hospitalized cases over positive COVID-19 cases across states.

Notes

1 Credit rating agencies consider the comprehensiveness of a company’s business continuity and disaster recovery plans when assessing a firm’s overall creditworthiness. They, for instance, look at the disruptions when transitioning firm’s operations to a remote work environment and whether a firm can maintain a sufficient staffing level to support their businesses in their credit rating reports. The rating guidance is available at https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/201116-servicer-evaluation-spotlight-report-social-and-governance-factors-have-consistently-powere-11723045 (retrieved on June 20, 2022).

2 We also consider a battery of alternative explanations and find that WFH suitability has an influence on credit ratings that is independent of CEO ability, risk-taking incentives, CEO overconfidence, and accounting quality. In addition, WFH suitability has an effect on credit risk assessments that is independent of corporate governance and other monitoring mechanisms such as financial analysts, institutional investors, and board quality. Furthermore, we use the proportion of WFH suitability that cannot be explained by firm fundamentals and further confirm that WFH suitability is important, incremental to firm fundamentals, in credit rating assessments.

3 Liberti and Petersen (Citation2019) identify hard information as recorded numbers such as those from financial statement reports or exchange trading activities. Soft information includes opinions, ideas, rumors, economic projections, statements of management’s plans, market commentary and such information is not immediately quantifiable.

4 This is a form of telecommuting that can be defined in the economic literature as ‘work arrangement in which employees perform their regular work at a site other than the ordinary workplace, supported by technological connections’ (Fitzer, Citation1997, p. 65). There are three principal components of telecommuting: i) utilization of information technology, ii) links with an organization, and iii) de-localization of work (Pinsonneault & Boisvert, Citation1996).

5 While experimental studies have their strengths in internal validity, the generalization of these results is difficult because these experiments are conducted on subgroups of employees in a single firm and they lack external validity. Using theoretical modelling, Rupietta and Beckmann (Citation2018) offer a more generalized explanation for WFH productivity gains in that working from home increases employee’s intrinsic motivation, and thus their work efforts.

6 Anecdotal evidence suggests that risk assessments likely incorporate workplace arrangements. In their report for Zenith Service S.p.A in 2021, Standard and Poor’s ranked the company strong in terms of management and organization with a stable outlook due to its quick transition to remote working during the pandemic. In their report, S&P stated that the company ‘implemented the opportunity to work from home and flexible working hours during 2019, which made the transition for most of their staff to work remotely in response to this pandemic relatively seamless to their operations’. Link: The S&P report can be access from https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/211213-servicer-evaluation-zenith-service-spa-12206110 (retrieved on July 10, 2022).

7 Debt holders are more likely to value firms’ ability in limiting default risk (Merton, Citation1974). It is, therefore, unclear if higher stock returns and lower return volatility, equity attributes associated with WFH suitability as documented in Bai et al. (Citation2020), are relevant to debt holders.

8 The adoption of WFH is not without critique and concerns. A review of the literature on telecommuting Pinsonneault and Boisvert (Citation2001) suggests that WFH can result in reduced productivity, weak morale, and even mental health issues as conflicts may arise between family and work-related roles. Clark (Citation2000) also suggest that the separation between home and work is an important division for workers’ mental wellbeing. Because WFH can blur this distinction, this can negatively affect employee morale and productivity.

9 Our sample begins in 2010 as it is the first year the WFH suitability data is available. Our credit rating sample ends in 2020 according to the latest coverage in Capital IQ’s S&P Rating database at the time of writing this paper.

10 Compustat database stops updating S&P credit rating since early 2017. For rating data from 2017 onwards, we follow the literature (e.g., Pham et al., Citation2022) and source credit rating data from Capital IQ database.

11 Appendix B provides a detail discussion of credit rating classifications.

12 We thank the Editor for suggesting this measure.

13 We thank John Bai, Wang Jin, Sebastian Steffen, and Chi Wan for sharing the working-from-home data.

14 In a recent global survey conducted by ManPowerGroup Solutions, about 40 percent of the surveyed candidates report that schedule flexibility is one of the top factors they consider when making career decisions. The survey is available at: https://www.manpowergroupsolutions.com/wps/wcm/connect/976d951f-5303-41d4-be36-4938169d2d80/ManpowerGroup_Solutions-Work_for_Me.pdf. (retrieved on May 20, 2022)

15 WFH can place a negative impact on employee productivity. The inconclusive conclusions on the association between WFH and firm productivity is, therefore, an empirical question.

16 We also cluster standard errors by industry, by year, or by both industry and year, and find the results (untabulated for brevity) are qualitatively unchanged.

17 In Appendix OA5, we employ an instrumental variable approach to further address the concern that our OLS estimates could be biased by omitted variables that correlate both with flexible workplace arrangements and with credit risk assessments. We propose the economic conditions when a CEO enters the labor market can serve as an instrument for the CEO’s decision for advancing flexible work arrangements. Section B3 in the Online Appendix discusses rationales behind our choice of instrumental variable and Table OA5 reports the results for this test. Results from the 2SLS estimations consistently suggest that firms with higher WFH suitability have more favorable credit ratings.

18 For example, S&P considered LNR Partners LLC’s financial position to be sufficient, affirmed their overall strong ranking with stable outlook due to the firm’s good disaster recovery and business continuity plan. LRN almost experienced no disruption in their operations when all of their employees worked from home. In the report, S&P stated that: ‘we believe LNR has a deep bench of experienced workout personnel that it can redeploy across the servicing platform to maintain adequate staffing to mitigate the anticipated increase in special servicing volume … ’. The S&P report can be assess from https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/200618-lnr-partners-llc-strong-special-servicer-ranking-affirmed-outlook-is-stable-11536311 (retrieved on July 10, 2022).

19 The sample for the path analyses consists of the intersection of all variables in the baseline sample and two mediating variables, including firm-level productivity and volatility of future cash flows.

20 The number of observations in each of the cross-sectional analyses in depends on the availability of the cross-sectional variables and the nature of the tests.

21 This finding complements a recent report from Moody Ratings showing that expected corporate default rate in the U.S. approached 6.2% percent in July 2020, the highest level since May 2010. Moody’s report is available at: https://www.moodys.com/creditfoundations/Default-Trends-and-Rating-Transitions-05E002.

22 We also conduct a univariate analysis by forming portfolios based on firms’ working-from-home suitability scores during the pre-COVID-19 period (2010-2019). Specifically, we sort stocks into decile portfolios based on their average WFH scores over the period of 2010–2019 and compute the expected default frequency in the first and second quarter of 2020 by taking the average of the expected default frequency across all stocks in the portfolio. These univariate results, reported in Appendix OA8, establish a negative relation between a firm’s WFH suitability prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and its expected default frequency during the pandemic at the univariate level.

23 We thank Tarek Hassan, Stephan Hollander, Laurence van Lent, Markus Schwedeler, and Ahmed Tahoun for making the firm-level exposure to COVID-19 data available at https://www.firmlevelrisk.com/.

24 In addition, in the Online Appendix, we find that the effect of WFH suitability on default risk is stronger among firms located in high-incidence states (Appendix OA9). Furthermore, firms with high WFH suitability are less likely to exhibit employment- and operation-related violations in times of crisis such as the COVID-19 outbreak (Appendix OA10).

25 To date, our knowledge regarding the implications of large-scale global crises for organizations and societies has remained meagre. The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly reverberated across the global economy and caused a series of instant policy responses (Augustin et al., Citation2022; Gormsen & Koijen, Citation2020; O'Hara & Zhou, Citation2021; Peter Hansen, Citation2020; Philippon, Citation2021). In a few months, firms have adopted WFH at an unprecedented scale to comply with mandated workplace closings, limiting residential movement, and physical distancing.

26 We also acknowledge that the concept of WFH carries more nuances than what an empirical construct may capture. For example, operations of certain business activities may heavily depend on the staff that cannot work from home such as warehouse employees and delivery crews. At the same time, WFH is not without negative effects (Pinsonneault & Boisvert, Citation2001). It is, therefore, a fruitful research avenue to better refine the measurement of WFH suitability or examine how corporate policies and systems, as a control and surveillance mechanism, help firms transition into WFH efficiently.

References

- Acharya, V. V., & Steffen, S. (2020). The risk of being a fallen angel and the corporate dash for cash in the midst of COVID. CEPR COVID Economics 10. Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(3), 430–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa013

- Albuquerque, R. A., Koskinen, Y., Yang, S., & Zhang, C. (2020). Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(3), 593–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa011

- Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1968.tb00843.x

- Apgar, M. (1998). The alternative workplace: Changing where and how people work. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 121–136.

- Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., & LaFond, R. (2006). The effects of corporate governance on firms’ credit ratings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(1-2), 203–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.02.003

- Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Suh, J. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and credit ratings. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(4), 679–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1714-2

- Augustin, P., Sokolovski, V., Subrahmanyam, M. G., & Tomio, D. (2022). In sickness and in debt: The COVID-19 impact on sovereign credit risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 143(3), 1251–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.009

- Bae, K. H., El Ghoul, S., Gong, Z. J., & Guedhami, O. (2021). Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Corporate Finance, 67, 101876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101876

- Bai, J., Brynjolfsson, E., Jin, W., Steffen, S., & Wan, C. (2020). The future of work: Work from home suitability and firm resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Working Paper. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper (No. w28588).

- Bailyn, L. (1988). Freeing work from the constraints of location and time. New Technology, Work and Employment, 3(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.1988.tb00097.x

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Beaver, W. H., Shakespeare, C., & Soliman, M. T. (2006). Differential properties in the ratings of certified versus non-certified bond-rating agencies. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 303–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.06.002

- Bélanger, F. (1999). Workers’ propensity to telecommute: An empirical study. Information & Management, 35(3), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(98)00091-3

- Bharath, S. T., & Shumway, T. (2008). Forecasting default with the Merton distance to default model. Review of Financial Studies, 21(3), 1339–1369. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn044

- Bloom, N., Kretschmer, T., & Van Reenan, J. (2009). Work-life balance, management practices and productivity. International Differences in the Business Practices and Productivity of Firms, 15–54. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226261959.003.0002

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032

- Bonsall, IV, S. B., Holzman, E. R., & Miller, B. P. (2017). Managerial ability and credit risk assessment. Management Science, 63(5), 1425–1449. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2403

- Brogaard, J., Li, D., & Xia, Y. (2017). Stock liquidity and default risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.03.003

- Brynjolfsson, E., Horton, J. J., Ozimek, A., Rock, D., Sharma, G., & TuYe, H. Y. (2020). COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper (No. w27344).

- Callen, J. L., Segal, D., & Hope, O. K. (2010). The pricing of conservative accounting and the measurement of conservatism at the firm-year level. Review of Accounting Studies, 15(1), 145–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9087-6

- Carruthers, B., & Cohen, B. (2010). Calculability and trust: Credit rating in nineteenth century america. In Transitions to Modernity Workshop. Working Paper. Northwestern University.

- Cheng, M., & Subramanyam, K. R. (2008). Analyst following and credit ratings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(4), 1007–1044. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.25.4.3

- Chintrakarn, P., Treepongkaruna, S., Jiraporn, P., & Lee, S. M. (2020). Do LGBT-supportive corporate policies improve credit ratings? An instrumental-variable analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4009-9

- Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

- Clarkson, P., Li, Y., Richardson, G., & Tsang, A. (2019). Causes and consequences of voluntary assurance of CSR reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(8), 2452–2474. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2018-3424

- Cornaggia, J., Krishnan, G. V., & Wang, C. (2017). Managerial ability and credit ratings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(4), 2094–2122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12334

- Cronqvist, H., & Yu, F. (2017). Shaped by their daughters: Executives, female socialization, and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Financial Economics, 126(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.09.003

- Decker, R. A., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2017). Declining dynamism, allocative efficiency, and the productivity slowdown. American Economic Review, 107(5), 322–326. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171020

- DeFond, M. L., Lim, C. Y., & Zang, Y. (2016). Client conservatism and auditor-client contracting. The Accounting Review, 91(1), 69–98. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51150

- Ding, W., Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2020). Corporate immunity to the covid-19 pandemic (No. w27055). National Bureau of Economic Research. Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

- Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home?. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

- DuBrin, A. J. (1991). Comparison of the job satisfaction and productivity of telecommuters versus in-house employees: A research note on work in progress. Psychological Reports, 68(3_suppl), 1223–1234. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.68.3c.1223

- Dutcher, E. G. (2012). The effects of telecommuting on productivity: An experimental examination. The role of dull and creative tasks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 84(1), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.04.009

- Edmans, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.021

- Fahlenbrach, R., Rageth, K., & Stulz, R. M. (2021). How valuable is financial flexibility when revenue stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. The Review of Financial Studies, 34(11), 5474–5521. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa134

- Fitzer, M. M. (1997). Managing from afar: Performance and rewards in a telecommuting environment. Compensation & Benefits Review, 29(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/088636879702900110

- Gallup. (2020). Gallup’s data brief on COVID-19. Available at https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/305741/gallup-data-brief-covid.aspx Accessed on July 15, 2020

- Giurge, L., & Bohns, V. K. (2020). 3 tips to avoid WFH burnout. Harvard Business Review.

- Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 107–156. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535162