?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines how enforcement of acquisition disclosure regulation affects investors’ assessment of the transactions’ quality at merger and acquisition (M&A) announcements. Using a novel sample of comment letters on acquisition filings by public companies in China, we document that regulatory requests for disclosure enhancement and clarifications are more common on lower quality transactions obfuscated by weaker disclosure as evidenced by (i) a lower likelihood of the deal closing, and if the deal does close, lower post-deal firm profitability; and, (ii) a greater likelihood of subsequent goodwill impairment. Using entropy balancing matching, we document that transactions that receive comment letters associate with significant negative bidder announcement returns suggesting that regulatory actions reveal new information that aids investors to identify lower quality deals. The negative price effect is greater when comment letters have more acquisition-specific comments, compared to letters with more comments on general accounting and governance issues. Our results showcase that enforcing disclosure compliance in M&A filings aids investors in assessing the quality of M&A transactions at the time when the filings are made public.

1. Introduction

There is significant interest and ongoing debate on the security regulators’ role in capital markets, revitalized by the financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote1 This discussion has focused on regulators’ roles in setting accounting standards, the usefulness of accounting disclosures, and the need for disclosure compliance enforcement (e.g., Ball & Brown, Citation1968; Ball & Shivakumar, Citation2008; Barth et al., Citation2001; La Porta et al., Citation2006; Leuz & Verrecchia, Citation2000). However, the literature has paid little attention to examining if enforcement actions on corporate filings affect their usefulness when they become public, which is when investors assess the information in the filings. We address this gap by studying how enforcement actions on mergers and acquisitions (M&A) filings affect their usefulness at the time of public announcement in China. We assess usefulness by examining the impact of regulatory enforcement actions on M&A filings on price reactions to M&A announcements (see Khan et al., Citation2018; Lev & Gu, Citation2016).

We focus on M&A filings as these events are economically significant and provide an ideal setting to understand how regulatory actions impact investors’ decision-making. M&A events are vital for capital allocation, firm productivity, and mitigating managerial entrenchment (Bonetti et al., Citation2020; Dimopoulos & Sacchetto, Citation2017). However, M&A filings often suffer from information asymmetries and strategic disclosures to promote deals (e.g., DeAngelo, Citation1990; Eckbo et al., Citation1990; Hansen, Citation1987). Investors have limited time to gather, process, and react to acquisition announcements. This makes the information disclosed with an M&A announcement crucial for evaluating the deal, making the decision-usefulness of disclosure compliance enforcement more important. This makes the information disclosed with an M&A announcement important for evaluating the deal, and therefore decision-usefulness of disclosure compliance enforcement becomes heightened.

We focus on China, where regulators review all mandatory acquisition filings with the objectives of (i) ensuring compliance with disclosure regulations, (ii) maintaining market stability, and (iii) protecting bidder shareholders. The regulator issues comment letters if the M&A filings’ disclosures do not meet the minimum requirements. These comment letters are a record of the regulator's required disclosure modifications. At the time of merger announcements, investors learn about the content of the merger filings and, if the filings were initially considered deficient by the regulator, the content of the comment letters on the original filing and the company's response. If investors find this enforcement action information useful, they will trade on it, leading to changes in share prices.Footnote2

We propose that the regulatory review of merger filings, if effective at correcting distorted filing disclosure, or eliciting strategically withheld but mandatory information, will increase the amount and precision of information disclosed on the M&A announcement – in the form of the merger filing, comment letters and managers’ responses –, which in turn will aid investors in identifying lower quality transactions obfuscated by deficient disclosures. Low precision and incomplete merger disclosures increase the uncertainty of valuation estimates leading to greater estimate overlap of poor-quality transactions with higher quality deals (Akerlof, Citation1970; Board, Citation2009; Cheong & Kim, Citation2004; Grossman & Hart, Citation1980; Jovanovic, Citation1982). Thus, lower quality deals with deficient disclosures can be misvalued as investors find them harder to distinguish from higher quality deals. This effect is magnified by strategic managerial disclosures that promote the transaction (DeAngelo, Citation1990; Eckbo et al., Citation1990; Hansen, Citation1987).Footnote3 Comment letters can provide (i) additional disclosure and (ii) increase the precision of filing disclosure with both helping investors identify poor quality transactions. For example, requests for clarification of the offer price can reveal the bidder’s valuation method and assumptions, which in turn help investors to identify deals with overly optimistic expectations.Footnote4 Thus, we expect transactions that receive comment letters to have a corresponding negative association with the stock price response to the bidders’ announcement, as increased amount and informativeness of disclosure leads to a stronger impounding of the signal that the deal is of low quality into stocks prices. To validate that regulatory interventions help investors to identify lower quality transactions, we expect transactions with comment letters to associate with relatively poorer longer-term merger outcomes as proxied by lower completion rates, lower future firm profitability, and greater future goodwill impairment.Footnote5 To support that deficient disclosures that prompt regulatory interventions associate on average with lower quality transactions, we examine how deal quality associates with the likelihood of receiving a comment letter.

We examine comment letters issued by the Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges on behalf of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) for acquisitions by public bidders announced from 2015 through 2017. Out of 2,167 acquisitions, 26.90 percent received a comment letter requesting modified disclosures. These comment letters contained an average of 25.8 (26) comments, with a mean of 15.01 (15) comments relating to acquisition disclosure issues, 7.3 (7) relating to accounting disclosures, and 3.4 (3) relating to corporate governance issues.Footnote6 Thus, a significant proportion of merger filings elicit a regulatory intervention, and the additional disclosures are unlikely to be available to market participants without the action of the comment letter, indicating that it can potentially provide value to investors.

We then turn to our central questions of whether the disclosure of the regulator’s intervention and of the information in firms’ responses to comments affects investors’ trades around the merger announcement. To build confidence that our results capture a causal relation, we use entropy balancing matching (Hainmueller, Citation2012; McMullin & Schonberger, Citation2018), which aims to balance the mean, variance, and skewness of the covariate distribution between the treatment (comment letter firms) and control groups (firms that did not receive comment letters). This increases the likelihood that the differences in outcomes are due to comment letter disclosure rather than correlated differences in covariates. The method also dispenses with the need to specify a model to estimate the propensity score and allows for non-linearities to affect the matching process.

We find that deals with comment letters experience 6.81% lower announcement returns compared to those that do not receive comment letters. Given that the mean bidder announcement returns are 0.6% when no comment letter is present, comment letter disclosure prompts a 10.35-fold more negative price reaction. The negative price reaction to the deal announcement increases with the intensity of the regulator’s M&A comments – comment letter firms with the total number of concerns in the top quartile have on average 2.1% lower price reactions than firms in the bottom quartile (untabulated). Our evidence is consistent with comment letters (i) helping investors to identify lower quality transactions and (ii) materially affect investors’ assessment of these transactions’ benefits increasing the magnitude of price reactions to these deals.Footnote7

To support the conclusion that comment letters increase the informativeness of merger disclosures, we show that when comment letters are present, more information enters stock prices on the M&A announcement relative to all information discoverable around the announcement, e.g., through investors costly information acquisition. Further, we find no evidence of post-announcement price reversal, which suggests comment letters disclosures do not lead to overreaction that corrects after the announcement.

We conduct a series of tests to examine the extent to which the effect we document is a result of the regulator enhancing informativeness of merger disclosure, rather than that the enforcement action that merely associates with lower-value deals that would have been identified by investors even without the regulator’s intervention. We find evidence consistent with regulator’s comments revealing valuable information when (i) we control for unobserved time-invariant bidder characteristics, (ii) use instrumental variables regressions where the identification is based on regulatory busyness (Fich & Shivdasani, Citation2006; Gunny & Hermis, Citation2019; Lopez & Peters, Citation2012; Tanyi & Smith, Citation2015), (iii) use counterfactual samples based on propensity score matching, and (iv) apply the Altonji et al. (Citation2005) test to assess the extent to which omitted variables can explain our results. Additional tests significantly reduce the likelihood that our conclusions are due to omitted correlated variables, however, we recognize that we cannot completely rule out this alternative explanation.

To validate that regulators more commonly ask for clarification on low quality deals’, we perform two tests. First, we document that regulatory requests for disclosure enhancement are more frequent for deals with characteristics that associate with high information asymmetry and poor outcomes (e.g., Ambrose & Megginson, Citation1992; Berger et al., Citation1996; Bhagwat et al., Citation2016; Moeller et al., Citation2007; Travlos, Citation1987). Second, we compare post-announcement outcomes for transactions with and without comment letters. We find that comment letter deals are less likely to complete, a finding that supports the regulator’s objective of targeting deals that associate with higher risk of market instability as deal cancelations are associated with negative price reactions (Davidson et al., Citation1989). Failed deals also present a higher likelihood of managerial turnover (Lehn & Zhao, Citation2006) and firm distress (Dassiou & Holl, Citation1996). For deals that do close, we document that comment letter firms have poorer subsequent operating performance and a higher likelihood of future goodwill impairment, indicating overpayment relative to the value received by the acquiring firm (Gu & Lev, Citation2011). Further, bids that receive comment letters associate with a longer period of share trading suspension measured by the number of days between the M&A announcement and the first trading day after the announcement. Jointly, these results suggest that regulatory actions help investors to identify transactions more likely to experience comparatively worse outcomes.

2. Background and the Chinese Acquisition Setting

To protect investors and promote transparency and price discovery, regulators mandate that acquisition-related disclosures include material information about the transaction. However, despite these disclosure requirements, merger filings may be deficient in providing required information, or may exaggerate certain aspects of the deal, which impedes investors’ ability to assess and trade on the merger news. We focus on regulatory interventions through the enforcement channel of comment letters, building on the literature that examines the consequences of comment letters on annual filings (Dechow et al., Citation2016; Duan et al., Citation2023; Johnston & Petacchi, Citation2017).

2.1. Regulatory Objectives and the M&A Filing Review Process in China

We take advantage of the unique nature of the Chinese setting to examine the impact of regulatory reviews on the market response to acquisition announcements.Footnote8 The CSRC, acting through staff at the Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges, requires publicly-traded bidders to submit a standardized set of filings when announcing a material acquisition, including financial statements, proof of funds for cash transactions, a merger plan, and a justification for the offer price, before the deal can be publicly announced.Footnote9 These filings are reviewed with the objectives of compliance with disclosure regulation, market stability, and bidder shareholders’ protection.Footnote10 Filing compliance reflects the completeness of the filing documents as specified by the disclosure regulations. Market stability concerns the bidder’s ability to consummate the transaction, failure of which can lead to undesirable share price volatility, delisting, or bankruptcy risk for the bidder. Shareholder protection concerns relate to the avoidance of tunneling, or self-dealing by management and controlling shareholders.Footnote11 The regulator reviews all deals and if it considers the merger filings deficient in any of the three areas, it will issue a comment letter requesting changes, clarification, additional information or filing amendment. Market stability and shareholder protection objectives should incentivize the regulator to parse the deals and issue comment letter on lower quality transactions that are more likely to endanger these objectives.

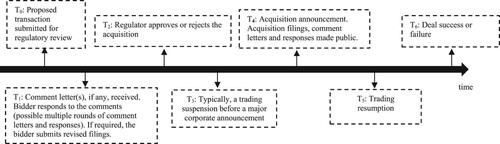

The bidder has to respond to the comment letter within seven business days. If the exchange is not satisfied with the response to the initial letter or did not receive it before the due date, it issues follow-up letters.Footnote12 If the overall response is not satisfactory, the exchange can withhold permission to proceed with the M&A transaction, launch an on-site inspection and issue monetary penalties. Satisfactory response to the letter is necessary for the regulator to approve the transaction, at which point the bidder is allowed to publicly announce the deal. Upon approval of the deal by the exchange, the bidder can apply for share trading to be suspended prior to making the public acquisition announcement, which is standard for disclosure of major corporate events in China. This trading suspension period serves to give investors time to process the information revealed at the deal announcement before the company shares start trading again and applies to both companies with and without comment letters.Footnote13 The trade suspension process aims to reduce abnormal price movement around the M&A announcement and provide time and sufficient information for investors to evaluate the news prior to trading resumption (CSRC, Citation2014). When the deal is announced, investors learn the transaction details from the filings, including if the bidder received any comment letters, the content of, and the response to the letters that were issued.Footnote14 Thus, the enforcement action, its outcomes in the form of the response to the comment letter and, if required, the amended acquisition filing, are all revealed precisely at the time investors assess the transaction and trade on the acquisition disclosure. illustrates an overview of the timeline of the M&A process in China from the bidder’s perspective.

It is not obvious that regulatory enforcement through comment letters will associate with significant negative market reactions. First, previous research documents that public disclosure of comment letters on 10 K and 10Q filings does not elicit significant price reactions (Dechow et al., Citation2016). Johnston and Petacchi (Citation2017, p. 1130) report that they ‘find little evidence that comment letters signal poor-quality reporting, leading to a loss of reporting credibility.’ Specific to the Shanghai Stock Exchange, Duan et al. (Citation2023, p. 1) do not find evidence that after the receipt of a comment letter, firms experience any ‘significant improvements in their information environments.’ Further, regulatory interventions in China may be light-touch and inefficient at correcting deficient disclosures. Liebman and Milhaupt (Citation2008) highlight that in the Chinese socialist market economy, regulators carefully balance the benefits of enforcement with the risk that regulatory actions endanger social stability, e.g., the risk of abnormal price volatility putting retail holdings at risk, or of firm bankruptcy that jeopardizes the employees’ livelihood.Footnote15 Thus, comment letters may not elicit a meaningful improvement in the amount and precision of merger filings. Thus, if and how M&A comment letters associate with bidder announcement returns is an empirical question.Footnote16

3. Data and Research Design

We collect acquisition, market, and firm accounting data from the CSMAR and WIND databases, with Appendix A providing details of the variables used in this study. We select bids by domestic public A-share firms, which ensures availability of financial and market data. We place no restriction on the public status of the target, nor on the industry of the acquirer or the target, to minimize the risk of sample bias (Netter et al., Citation2011). Following Lehn and Zhao (Citation2006), Masulis et al. (Citation2007) and Li et al. (Citation2018), we require an acquisition in our sample to satisfy the following conditions: (i) the acquisition is completed or withdrawn, (ii) the acquirer controls less than 50% of the target prior to the acquisition announcement and seeks to own 100% of the target firm's shares through the deal, and (iii) the annual financial statement information, stock return data, firm’s headquarters’ location, and deal-level information are available in the CSMAR and WIND databases. The resulting sample yields a total of 2,167 takeover bids between fiscal years 2015 and 2017. We start in fiscal year 2015, which is the first year M&A comments letters for firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges are available.

We hand-collect all comment letters from Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges’ websites and classify them as M&A related comment letters or those issued on annual and half-year reports and other restructurings. We retain only M&A related comment letters. We make sure the transactional comment letters and responses are made public on the M&A announcement day, and check there are no transaction-related comment letters issued after the transaction announcement. To identify types of regulatory concerns, we perform textual analysis of the letters’ content. We split the letters’ questions and concerns into three groups. MA_ITEMS measures the number of comments and questions related directly to the acquisition transaction disclosures, e.g., comments and questions related to the offer price or availability of funds needed to consummate the deal. Our analysis of all comment letters identified 28 types of comments related to the M&A transaction. A_ITEMS is the number of comments and questions an acquirer receives from the stock exchange, which relate to the bidder’s general accounting quality, e.g., questions or comments related to the firm’s goodwill balance and impairment testing. We identify 13 types of comments that capture accounting quality. G_ITEMS is the number of comments and questions related to bidder’s corporate governance mechanisms disclosed in the M&A filing, e.g., comments regarding the disclosures of significant shareholders, and disclosures regarding the relations between shareholders and the firm. We identify 8 types of questions that relate to bidder’s corporate governance. Online Appendix III lists the keywords we use to classify comments into each group (translated from Chinese) and online Appendix IV provides examples of comments in the three categories (translated from Chinese).Footnote17 The final sample consists of 583 deals that received comment letters and 2,167 non-comment letter deals.Footnote18 Panel A of Table 1 summarizes the sample selection process.

Table 1. Sample selection and M&A comment letter distribution over time.

Panel B of Table 1 reports the annual number of all acquisitions and the frequency of those with comment letters. The number of comment letters by year is 195 in 2015, or 25.36% of the sample observations, 258 in 2016 (35.1%), and 130 in 2017 (19.61%). Over our sample period, 26.90% of acquisitions receive a comment letter, representing a significant proportion of bidders for which the regulator identified potential disclosure deficiencies. Online Appendix V presents the sample breakdown by industry. We use the CSRC industry sector classification, which is assigned to each listed firm. The sectors with the greatest number of deals receiving comment letters is non-metallic mineral products manufacture, with 35.85% of all comment letters, followed by furniture manufacturing, paper products and printing, information transmission, and software and information technology.

3.1. Determinants of Receiving Regulatory Comments

Our first objective is to understand which transactions are more likely to attract regulatory requests for disclosure enhancement, by examining the factors associated with a comment letter disclosed at the deal’s announcement. This analysis aims to validate that the regulator targets high information asymmetry deals that make it challenging for investors to separate low quality transactions obfuscated by low quality filing from high quality deals. Further, the test gives insights into the mapping between the regulator’s stated objectives and bidder and deal characteristics, thus speaks to the efficacy of regulatory supervision. The basic model specification is:

(1)

(1)

where the dependent variable Letter is an indicator equal to 1 if an acquisition receives a comment letter, and 0 otherwise. The set of controls includes (i) merger filing variables, (ii) deal characteristics. (iii) bidder characteristic, and year and industry fixed effects. We motive their inclusion in the online Appendix II.

3.2. Bidder Announcement Returns and Comment Letter Disclosure

To examine our main research question on how shareholders respond to the regulator’s enforcement action, we consider abnormal returns around the acquisition disclosure event, which capture the investors’ assessment of the net benefit an acquisition is expected to bring to the acquirer’s shareholders (Betton et al., Citation2008; Cai et al., Citation2016; Halpern, Citation1983; Jarrell et al., Citation1988; Jensen & Ruback, Citation1983). We focus on acquirer’s price reaction because the demand for transaction-related information is stronger with bidder shareholders (Jarrell & Poulsen, Citation1989; Servaes, Citation1991), and the number of public-target acquisitions in China is small. We expect that additional disclosure prompted by the comment letter will increase the informativeness of the merger filings, which in turn will help investors separate lower quality transactions, obfuscated by low quality disclosures, from high quality deals. This in turn should promote stronger negative price response to merger announcement for firms that received and responded to comment letters compared to firms not subject to regulatory intervention.Footnote19 The regression model has the form:

(2)

(2)

where CAR is the seven trading-days cumulative abnormal return surrounding the M&A announcement date, which is also the date when the comment letter is made publicly available on the exchange’s website. β1 captures acquirer’s incremental price reaction to receiving a comment letter and we expect this coefficient to be negative. Controls include independent variables from model (1) to account for the possible impact that these variables have on bidder returns, separate from the comment letter disclosure. Year and industry effects account for heterogeneity in price reactions over time and across industries and the resulting serial correlation of residuals. Standard errors are robust to within-industry serial correlation (Rogers, Citation1993) and are adjusted for heteroskedasticity (White, Citation1980).

Chinese companies typically suspend share trading before announcing major corporate events with share trading resuming shortly after the M&A announcement, we classify as day 0 the first trading day after the announcement, and day −1 is the last trading day before the M&A announcement.Footnote20 Bidders request trade suspension before the announcement without providing detailed information to the public for the suspension reason with the justifications ranging from more specific – ‘we plan to conduct an M&A’ to more vague ones – ‘we are planning a major event’. Trade suspension request can be filed after trading hours, with the M&A announcement scheduled for the next day and share trading resuming shortly after the announcement (see also Huang et al., Citation2018). Online Appendix Figure I shows the mapping of events.

3.3. Endogeneity Concern

The variable Letter in model (2) may be endogenous if some omitted variable that can be observed by investors predicts both comment letter issuance and the bidders’ abnormal announcement returns. To address this potential alternative explanation for the association between comment letter issuance and bidder returns, we perform all analyses using entropy balancing method (Hainmueller, Citation2012; McMullin & Schonberger, Citation2018). Specifically, we create a sample of comparable non-comment letters M&A transactions which we match to the sample of M&A transactions that receive comment letters. We balance covariates on the three moments for all covariates using the pooled sample. We then compare price announcement effects across the two groups and argue that any differential performance is attributable to the comment letter disclosure. In contrast to the popular propensity score method (PSM), which matches controls on the closest propensity score, entropy balancing aims to balance the mean, variance and skewness of the covariate distribution between the treatment and control groups. This increases the likelihood that the difference in outcomes is due to the treatment effect rather than to the correlated differences in covariates. The method also dispenses with the need to specify a model to estimate the propensity score and allows for non-linearities to affect the matching process.

To build confidence for the causal interpretation of our results, we perform three additional tests. First, we add firm and year fixed effects to our analysis. This analysis captures the impact of comment letters keeping constant the firm’s political relationships, time effects and other time-invariant factors that might correlate with the comment letter issuance and price reactions to M&A announcements. Second, we apply an endogenous treatment regression model (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2005; Wooldridge, Citation2010) where we first model the regulatory decision to issue a comment letter. The 2SLS model is:

(3)

(3)

and

The auxiliary equation captures the regulatory decision process which we model in Equation (1). If regulator’s concerns regarding the quality of the transaction are non-zero, it will issue a comment letter, otherwise the firm does not receive the letter. Because we use the same set of controls in the logistic regression (first stage) and in the pricing equation (second stage), we need an instrument in the first stage regression. The instrument we use is the exchanges’ busyness, which we capture by the volume of both periodic and IPO filings in the month leading up to the acquisition announcement, scaled by the total volume of IPO and periodic filings over the previous two months. The CSRC mandates that Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges review all half-yearly, annual, and IPO filings, which can impede their ability to provide detailed reviews and issue comments on M&A filings during busy periods. Lower regulatory ability to process information should affect the likelihood of receiving a letter, but not price reactions to the bidder’s M&A announcement, except through the effect of the letter itself, and so the instrument should meet both the exclusion and the relevance criteria. Together with the non-linearities inherent in estimating the first stage model, the instrument helps us reliably estimate the set of equations. Third, we create a sample of comparable non-comment letters M&A transactions using propensity score method (PSM). For this method, we first use the logit model from Equation (1) to calculate propensity scores for each firm in the sample and then match each firm that received a comment letter (treated firm) with a peer firm that did not receive the letter (control firm), but with the closest propensity score and a score difference no larger than 0.02.

3.4. The Intensity of Regulatory Monitoring and Price Reactions to Comment Letter Disclosure

We next consider how the variation in regulatory intensity affects abnormal returns, which supports the contention that information revealed by comment letters is value-relevant to bidder shareholders. If regulatory monitoring is superficial or focused on filings’ completeness, measures of review intensity should not correlate with price reaction to comment letter disclosures. Because we rely on a cross-sectional variation within the comment letter sample, which keeps constant the correlations between the propensity to issue the letter and omitted correlated variables, this test helps us to identify the effect of comment letters beyond that of omitted variables. We consider variables that proxy for the overall variation in regulatory intensity and measures of specific disclosure deficiencies and remediation costs (e.g., Cassell et al., Citation2013).

First, we measure the length of the comment letter in terms of the number of words, CL_Complexity, because longer letters are likely to reflect a larger number of comments and questions the bidder must address, which in turn can signal more risky transactions. We scale the total number of words in a letter by the length of the longest comment letter to bound the measure in the range [0, 1]. Next, we also consider the category of questions to be able to infer the type of information that most strongly associates with investors’ reactions. To do so, we include counts of the questions in each category from the online Appendix III in Equation 2. Specifically, we include counts of MA_ITEMS, the number of comments and questions related directly to the acquisition transaction disclosures, A_ITEMS, the number of accounting comments, and G_ITEMS, the number of governance questions, and we sum all the issues to measure a total number of comments, ISSUES.

3.5. Comment Letters and Acquisition Outcomes

To validate those regulatory interventions, we identify lower quality transactions, and shed further light on the efficacy of the M&A regulatory intervention. We link comment letter receipts with four acquisitions outcomes: the likelihood of deal cancelation, post-acquisition operating performance, impairment of acquisition goodwill, and the duration between the merger announcement and resumption in share trading. If regulatory interventions are consistent with the stated objectives, we expect that they identify transactions which are more likely to be canceled after the deal announcement.Footnote21 We define a variable Completion, which is an indicator equal to 1 if the M&A transaction is completed, and 0 if the deal is withdrawn. We then use it as the dependent variable in Equation (2) and estimate the regression using maximum likelihood.

If the regulator identifies transactions more likely to deliver disappointing outcomes, we expect comparatively poorer post-acquisition performance of bidders that receive comment letters. To test this predication, we calculate the change in operating performance, measured as the difference in ROA three years after the acquisition compared to the merger year t, ROA(t + 3) – ROA(t), which we then use as a dependent variable in Equation (2). We focus on accounting rather than market performance because stock returns embed future expectations and may be biased due to market sentiment or investor’s perceptions (Fich et al., Citation2016).

If comment letters associate with M&A transactions likely to overstates the value of assets, the goodwill recognized from M&A deals will have a greater chance of being impaired when the overpricing becomes clear to investors and managers in subsequent periods. We expect that acquirers with comments letters will be more likely to impair goodwill after the transaction. Variable Goodwill Impairment is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the acquirer confirms that goodwill impairment has been reported after the merger, and 0 otherwise. We then use Goodwill Impairment as Equation (2) dependent variable and estimate the model using maximum likelihood.

Upon the request of the bidder, the exchange can halt trade in bidder’s stock to allow investors to process the announcement day news and give the bidder the time to complete the negotiations and begin the integration of the target. The length of the suspension is set by managers and can be extended upon a firm’s request.Footnote22 A longer duration of bidder’s stock price suspension after the merger announcement may indicate more challenges to negotiate or integrate the target, such as the discovery of ‘material adverse effects’ during the due diligence process that can lead to renegotiations or bid withdrawal.Footnote23 Long share suspension is also costly to investors who would normally trade in the bidder’s stock, e.g., for liquidity reasons. If comment letters indicate more challenging deals, the time to relist is likely to be longer. We create a variable Time to relist that measures the number of days between the merger announcement date and the share trading resumption date. We then use Equation (2) with log (1 + Time to relist) as the dependent variable.

4. Descriptive Statistics

Panel A of Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for comment letter characteristics for our sample of 583 M&As that receive a comment letter. The average length of the letter is around 2,566 words and the average number of comments in the letter is 25.8 out of 49 potential issues. An average letter includes around 15 out of 28 potential M&A issues, 7 out of 13 accounting issues and 3 out of 8 corporate governance issues.Footnote24

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Panel B shows annual averages for the number of issues mentioned in each of the three categories we identify. We observe that the proportions are relatively stable over the sample period, for example, the average number of M&A related comments is 13.9 in 2015 with a maximum value of 15.26 in 2016. Thus, the M&A deals that receive comment letters are relatively comparable across years in terms of the number of comments they receive.

Panel C presents Pearson correlations between CAR (−3,3) and comment letter characteristics. Price reactions are negatively correlated with the Letter dummy (Pearson correlation of 0.214) and with characteristics of comment letters. This result provides preliminary support for the pricing effect of M&A comment letters.

Panel D reports descriptive statistics for Equation (1) variables for firms with a comment letter (Letter = 1) and without a comment letter (Letter = 0). We observe that price reactions to M&A announcements are significantly lower for firms that receive comment letters with the mean difference of −0.6%. This result supports our correlation evidence that comment letters send a negative signal to the market. Comment letter firms also have lower completion rates, weaker post-deal ROA, and longer time for share trading resumption. These results provide preliminary evidence that the regulatory intervention identifies potentially lower quality transactions.

We examine the nature of the M&A disclosures prompted by the comment letters. Specifically, we split the M&A issues listed in the online Appendix III into six categories that relate to offer pricing, the payment method, target, deal risk, deal integration and other. Reported in online Appendix Table I, we find that 93.2% of comment letters ask for additional pricing and valuation-related disclosures, 92% of letters include questions about the payment method, 95.1% request more information about the target, 66% ask about the deal risk, and 85.3% about the integration plan. Thus, the regulatory intervention prompts the type of disclosures which is of high interest to shareholders, and which affects the deal pricing.

Examining the content of merger filings documents, we find that bidders that receive comment letters less frequently warn investors of the risks involved in the transaction and more frequently indicate that the transaction will involve a private equity placement. Jiang et al. (Citation2010) find a positive association between deals financed by private equity placements and minority shareholder expropriation. We also observe that comment letter bidders more frequently state that the transaction was approved by the board of directors, target assets have been appraised and their filings indicate a plan for the acquisition execution.

Looking at the control variables, firms that receive comment letters tend to have lower profitability and lower analyst coverage, but almost two times higher Tobin’s Q, higher return volatility and longer listing. Further, comment-letter firms are less likely to be state-owned, and interestingly, they have better corporate governance as indicated by a smaller proportion of managers on boards, though the CEO is less likely to have accounting background. Comment letter bidders also tend to pay with stock for the target, acquire relatively larger targets, choose more reputable financial advisors, and are more likely to engage in related party transactions.

5. Multivariate Analyses

5.1. The Likelihood of Receiving an Acquisition Comment Letter

Our first test examines if lower quality transactions are more likely to receive a comment letter. If the review meets the set objectives, the exchanges should target incomplete filings, deals with high information asymmetry where investors are disadvantaged in unravelling transaction benefits and transactions with high information asymmetries, defined as deals unlikely to complete, those at risk of bankruptcy after the transaction, or those with a high post-deal price volatility of the merged firm. The logistic regression results support these predictions. The CSRC targets ‘significant’ transactions where the acquisition materially increases bidder’s size, often in excess of 100 percent, and that involve private equity placements. Such transactions are at higher risk of shareholder expropriation. Regulators also target M&As where information asymmetries are higher, such as bidders with high stock return volatility. The economic significance of M&A risk proxies in explaining the likelihood of receiving a comment letter is high. To illustrate, bidders with higher return volatility have 12.9% higher odds to receive a comment letter.

CSRC is more likely to comment on transactions claiming not to represent major asset restructurings even though close to 73% of deals that receive comment letters are ultimately classified as major asset restructurings. This result suggests that potentially strategic phrasing of the merger filings does not reduce the likelihood of regulatory review as the regulator reclassifies such deals. Consistently, such as where filings state that the deal was approved by the board of directors, indicating an execution plan and that bidder’s assets were professionally appraised, are more likely to receive a comment letter. We find that hiring a top financial advisor does not mitigate the risk of receiving a comment letter, which suggests that top financial advisors do not reduce the risk of regulatory involvement. This result is in line with the literature which shows that hiring reputable investment banks does not associate with better outcomes for the bidder (Hunter & Jagtiani, Citation2003; Ismail, Citation2010; Porrini, Citation2006).Footnote25

We find that state-owned firms are less likely to receive a comment letter, with a 26.4% reduction in the odds of receiving a comment letter if a firm is an SOE. This result suggests that the politically connected firms may lobby directly with the exchanges and politicians who can influence regulatory outcomes and reduce the likelihood of regulatory scrutiny (Ferris et al. Citation2016) and consistent with previous evidence on a negative association between political connections and regulatory oversight (Correia, Citation2014; Fan et al., Citation2007; Mehta et al., Citation2020; Yu & Yu, Citation2011).

In sum, our evidence suggests that regulatory interventions are more common on deals that associate with high information asymmetries and uncertainty that the bidder can consummate the deal, and poor post-announcement performance (Ambrose & Megginson, Citation1992; Berger et al., Citation1996; Bhagwat et al., Citation2016; Moeller et al., Citation2007; Travlos, Citation1987). Thus, the regulator issues comment letters on deals where enhanced disclosure informativeness should materially help investors to assess deal quality improving announcement day information acquisition (Fisch et al., Citation2014).

5.2. Bidder Announcement Returns and Comment Letter Disclosure

We now move to our central analysis of the announcement day price reactions. Because Table 3 suggests significant variation in covariates between treated and control firms, we first use entropy balancing matching to create a sample of controls (non-comment letter firms) similar to the treated sample (comment letter firms). Panel A of Table 4 shows the quality of matching based on entropy balancing method and we find a similar covariate distribution between firms with and without comment letters. In untabulated results, we find that the mean (median) sample weights are 0.54 (0.16) and the top (bottom) quintile values are 0.09 and 1, and the largest five weights range from 7.24 to 4.4. We recognize that second moments do not always balance, as convergence required us to relax constraints, thus the findings are subject to these imbalances.

Table 3. The likelihood of receiving a comment letter and the fraction of comment letters with specific M&A issues

Next, we examine price reactions to comment letter disclosures using the sample of control firms from entropy balancing matching. Model 1 in Panel B of Table 4 reports Equation (2) results, which examine market reaction to the announcement that a bidder has received a comment letter. We confirm the univariate evidence that the market reacts negatively to the comment letter receipt. The price reaction for comment letter firms is 6.81% lower compared to firms that did not receive a letter. The mean bidder announcement returns when no comment letter is present is 0.6%, thus comment letter disclosure prompts a 10.35-fold more negative price reaction. Jointly with Table 3 evidence that comment letters are more common for high information asymmetry and lower quality transactions, Table 4 results suggest comment letters help investors to identify transactions with poorer prospects resulting in stronger announcement day price reactions.Footnote26

Table 4. Comment letter receipt and bidder announcement returns.

5.2.1. Relative information acquisition around the M&A announcement

If additional disclosures prompted by the comment letter increase investors’ relative information acquisition, we should observe relatively stronger impounding of the overall merger signal into stock prices on the M&A announcement date. In other words, compared to all information that investors acquire about the transaction, either through own information acquisition or through the M&A disclosure in the filings, the relative proportion of information revealed on the M&A announcements is higher when accompanied by the comment letter.Footnote27 This reflects that absent a comment letter, investors themselves would have to engage in costly information acquisition to remedy deficient disclosure in the M&A filings. For example, if managers recognize that certain public signals reveal a deal is of low quality, they have the incentive to obfuscate the signal, e.g., through low quality filing disclosure.

To test this prediction, we create a ratio of the abnormal return on day 0 (the first trading day after the M&A announcement, i.e., the trade resumption day) scaled by CAR (−3,3):. High values of the ratio for comment letter firms suggest that comment letters reveal relatively high levels of new information relative to all information uncovered by investors around the M&A announcement. This result is consistent with significant information content of comment letters. We focus on day 0 as comment letters should promote more impounding of M&A information on the announcement day. The denominator captures the information content discoverable around the M&A announcement - investors can engage in information search before the transaction, e.g., information leakage or deal anticipation (Haw et al., Citation2006) and after the deal announcement, e.g., if M&A disclosures is insufficient to assess the quality of the transaction.

Column labeled shows that comment letters prompt a 33% higher impounding of the total M&A signal measured around the M&A announcement compared to non-comment letter firms. Thus, comment letters seem to improve the relative amount of decision-relevant M&A disclosures that is revealed on the M&A announcement day, compared to non-comment letter firms. For example, a granular explanation of how the bidder arrives at the offer price that is prompted by the comment letter is of higher precision than an aggregate offer price for a deal without a comment letter.

Higher price reactions to M&A announcement can reflect investors’ overreaction. To exclude this explanation, we calculate two-year post-announcement abnormal returns. We use the emerging markets Fama and French (Citation1993) model as the normal return benchmark. In untabulated results, we do not find evidence of post-merger price reversal for comment letter firms, which suggests that the regulatory actions help reveal true firm value through investor trades at the M&A announcement.

5.2.2. Further tests addressing the endogeneity concern

Table 4 price reaction tests use entropy balancing matching to create a sample of non-comment letter firms with a similar distribution of covariates to comment letter firms. The goal is to help us rule out confounding effects of observable public signals that can correlate with the comment letter issuance. In this section, we present additional tests to address the endogeneity concern. To keep the results trackable, we continue using the sample of entropy balanced non-comment letter firms in these tests.

In our first test, we estimate Equation (2) after including firm-fixed effects. Firm-fixed effects capture unobserved time-invariant characteristics that could correlate both with the regulator’s decision to issue a comment letter and with the price reaction to M&A announcement. This analysis relies on serial acquirers where we can observe a variation in regulatory scrutiny in the form of comment letters (there are 504 firms that had more than one transaction over the sample period). The result in the column ‘Firm-fixed effects’ in Table 4 confirms significant negative coefficient on the comment letter dummy for this analysis.

To further address the endogeneity concern, columns ‘2SLS’ estimate the 2SLS model in Equation (3) where the first stage models the regulator’s choice of the M&A transaction to comment on, and the second stage adjusts for the selectivity in regulator’s choice. The instrument is the standardized volume of periodic and IPO filings which is negative and statistically significant in the first stage logit regression, consistent with the idea that regulatory busyness associated with a high volume of work reduces the likelihood of bidders receiving a comment letter. Controlling for the selectivity in deals for which regulators issue comment letters, we continue to find a significantly negative coefficient on the Letter dummy.Footnote28

Next, we address the issue that the share trading resumption can vary between comment letter vis-à-vis non-comment letter firms. This may result in a negative price reaction on the share resumption day for comment letter firms reflecting other news disclosed after the M&A announcement, such as earnings releases. We address this concern three-fold. First, we search for whether bidders announce earnings news between the merger announcement and the trade resumption dates but find no such cases. We also check the incidence of media and analysts’ reports for comment letter firms but find virtually no cases between the announcement and trade resumption dates. Second, we re-estimate Equation (2) only for bidders that resume trading within the three days of the merger announcement, which aligns trade resumption between comment letter and non-comment letter firms and reduces the impact of other news. Column ‘Trade resumed within 3 days’ in Panel B of Table 4 reports a significant and negative coefficient on Letter for this subsample (0.066) which indicates that constraining the time between the merger announcement and resumption day does not alter our original result with respect to the effect of comment letters. Third, if comment letters associate with a public signal that correlates with lower bidder quality, then the request for trade suspension should associate with a more negative price reaction as investors anticipate lower benefits of a potential, yet unknown, corporate transaction. Figure II in the online appendix reports the coefficients on Letter from Equation (2) where the dependent variables are individual abnormal returns from the event window AR (−3) to AR (3). We also report the regression intercept, which captures the price reaction to non-comment letter deals. We observe relatively similar abnormal return patterns for bidders with and without comment letters up until day −1 (trade suspension day) and starting from day 1 (a day after the trade resumption). However, there is a markedly different price pattern on the trade resumption day between the two groups of firms as investors discount the merger news. In sum, the tests that address potential impact of confounding variables corroborate our conclusion regarding the negative market effect of the comment letter disclosure.

To further address the endogeneity concern, we also create matched samples of comment and non-comment letter acquisitions based on the propensity score matching to receive a comment letter, rather than using entropy balancing. Online Appendix VIII reports that the average difference in announcement returns between comment letter and non-comment letter deals in the PSM matched sample is −5.24%. Because we remove transactions not on support, where quality matching cannot be ascertained, this evidence suggests that our results are unlikely to be driven by comment letter firms being very different to non-comment firms.

5.3. The Intensity of Regulatory Monitoring and Price Reactions to Comment Letter Disclosure

To help with identification that the comment letter content is useful to investors, our next test examines the pricing effect of the comment letters’ content. In this test, we keep constant the correlation between potential confounding factors and regulator’s propensity to issue a comment letter but vary the intensity of regulatory enforcement action. If regulatory comments are not enhancing merger filing disclosures, the nature and intensity of comments should not correlate with price reactions. Model (1) in Panel C of Table 4 shows that the negative price reaction to the M&A announcement is amplified if the bidder receives a more complex letter. A bidder in the top quartile of comment letter complexity has on average 2.57% lower price reaction compared to a bidder in the bottom quartile (result untabulated). This evidence implies that the information content of comment letters influences investors’ trades.

To study the impact of letters’ content and investors’ reaction to a specific set of concerns raised in comment letters, Model (2) in Panel C documents a more pronounced negative reaction when the overall number of comments and questions in the letter increases. Specifically, comment letter firms with the total number of concerns in the top quartile have on average 2.14% lower price reactions than firms in the bottom quartile (result untabulated). Model (3) shows that investors react negatively to comments specific to the M&A transaction and bidder’s corporate governance when these are included jointly in Equation (2). To estimate the economic effect of each comment type, we report standardized coefficients where the variables are normalized to mean of zero and unit standard deviation. Normalization adjusts for the higher number of M&A categories, which mechanically reduces the coefficient estimate compared to the accounting quality and corporate governance categories. We find that the pricing effect of M&A comments is 36.54% higher compared to corporate governance comments. This result confirms that the main informational role of M&A comment letters is to reveal new information about the transaction. The economic effects of M&A-related comments is significant – one additional comment reduces price reactions by 0.33%.Footnote29

In Panel D of Table 4, we examine the relation between the content of comment letters and its impounding on the announcement date relative to information acquired by investors around the M&A announcement, . We find that comment letters containing M&A concerns reveal relatively greater volume of new information on the M&A announcement date compared to all information discoverable around the M&A announcement. Thus, both tests that examine the total and the relative information content suggest that comment letters reveal useful information to investors.

To help identify specific drivers through which comment letters affect the M&A outcomes, we carry out the following (untabulated) analysis. First, we perform a cluster analysis and identify clusters of comments commonly issued together. We then select a group of most issued comments and perform a subsample analysis for the cluster. We find negative price reactions for this subsample confirming our main results. Second, because interpreting clusters is often challenging, we also manually identify the top five most common issues that the regulator asks about in the comment letters. These issues are included in more than 61% of comment letters and pertain to the value of assets, capital, income, and performance. We then perform a subsample analysis for this group and find evidence of a negative price reaction to comment letters mentioning these issues. Third, we identify ex-ante measures that signal low deal quality such as transactions by bidders with weak internal controls, and who choose to pay in stock for the target. We anticipate that investors are less surprised that such deals have received comment letters confirming their low quality, thus the comment letter effect on the announcement day price reactions should be smaller for such transactions. On the other hand, investors are likely to be more surprised and react more negatively when better quality transactions, such as transactions by bidders with higher analyst monitoring and pre-deal profitability, receive comment letters. We confirm both conjectures (results untabulated).

5.4. Comment Letters and Acquisition Outcomes

In this section, we validate the proposition that regulators target low quality transactions obfuscated by low quality filing disclosures by linking the comment letter to acquisitions outcomes. In Table 4, we use the entropy balanced sample of non-comment letter firms. First, we examine the relation between the receipt of a comment letter and the duration of the bidder’s stock trading suspension. Though the median time to relist is 0 in our sample, comment letters may identify deals that experience more challenges to negotiate or integrate the target after the deal announcement, thus associate with a longer duration between the merger announcement and resumption of stock trading. Column ‘Time to relist’ in Panel A of Table 5 presents regression results that suggest the time to resume trading is longer for comment letter deals compared to non-comment letter acquisitions.Footnote30

Table 5. Comment letters of M&A outcomes.

Second, we provide direct evidence that the regulator targets deals with a higher likelihood of delivering poor outcomes as measured by deal cancelation, in line with the CRSC M&A review guidelines (CSRC, Citation2014, Citation2016). Column ‘Completion’ in Table 5 presents the logit regression results examining whether receiving a comment letter affects the M&A completion likelihood. We find that receiving a comment letter has a negative effect on the completion rates and that the economics effect is significant: firms that receive comment letters have 7.2% lower odds for completing the transaction.Footnote31

If the acquisition fails to generate expected benefits, the bidder will be more likely to impair the goodwill arising from the acquisition. Column ‘Goodwill impairment (t + 1)’ in Table 5 documents that bidders in M&A deals with comment letters have 13.9% higher odds for impairing the goodwill one year after the transaction compared to transactions that do not receive comment letters. Footnote32

The next test examines the relation between comment letter receipt and the change in firm operating performance after relative to before the acquisition, measured by the return-on-assets (e.g., Heron & Lie, Citation2002). Results in Panel B of Table 5 suggest that in the acquisition year, comment letter firms do not experience a significant change in profitability relative to three years prior to the acquisition and compared to non-comment letter firms. Three years following the acquisition, comment letter firms have significantly lower profitability compared to non-comment letter firms. This result is consistent with the prediction that relatively poorer disclosure of comment letter firms is associated with less attractive acquisitions, and that the regulator can identify such deals and request additional disclosure. Overall, these results support our conclusion that comment letters are associated with deals that are less attractive for the bidder’s shareholders, and that the additional disclosure helps investors better assess deal prospects.Footnote33

We recognize that in some instances, comment letters may identify high-quality deals that have deficient filings, e.g., due to lack of managerial experience or skill in preparing the filings. Though identifying such transactions is difficult, we attempt to do it by looking at ex-post outcomes. Specifically, we code as one an indicator variable for deals that complete, and do not impair goodwill one-year after the transaction. We consider these as (ex-post identified) high-quality deals where lack of managerial skill in preparing the merger filing resulted in a regulatory action. We then augment Equation (2) with this measure and its interaction with the indicator for the comment letter. In untabulated results, we find that the coefficient on the interaction term is positive, which suggests that disclosure prompted by the comment letters helped investors identify these deals will have better outcomes.

6. Conclusions and Contribution

Drawing on a novel sample of acquisition filings and regulatory comment letters in China, we examine factors that shed light on the importance of regulatory reviews of acquisition disclosures. The specific nature of Chinese regulatory setting, where acquisition disclosures are reviewed by the regulator prior to the deal’s public announcement, and hence prior to observing the market’s assessment of the deal, allows us to examine the association between the regulator’s oversight and investors’ reaction to the deal. We find that regulators issue comment letters for bidders at higher risk of delivering poor acquisition performance, measured by changes in operating performance and future goodwill impairments. Investors react negatively to comment letter disclosure consistent with the comment letters helping investors identify low-quality deals obfuscated by low disclosure quality. We also classify the regulator’s comments to understand which types of issues are most value-relevant to bidder shareholders and find that acquisition-specific comments have a greater impact compared to those on accounting and governance issues. The comments appear to be useful to investors because they are also associated with a lower likelihood of deal completion, lower future profitability, and a greater chance of goodwill impairment. These results support the view that the regulator’s enforcement of acquisition related disclosures is effective from a public interest perspective. Our results also suggest that M&A disclosure reviews increase transparency and help investors better evaluate the expected benefits of a transaction. We use several methods to address endogeneity but acknowledge that ultimately, we cannot completely rule out that comment letters correlate with observable signals about deal quality. Overall, our study provides insights on how regulatory involvement brings substantial benefits to investors and market stability in countries with relatively lower degree of institutional structures and capital market development compared to the United States, but also on how regulatory enforcement of relevant disclosure in the M&A setting is useful for more sophisticated investors and in more mature markets.

A question that remains is why the bidder does not reverse the deal if they receive a comment letter and the letter disclosure associates with negative price reactions. Managers may decide to pursue a transaction accompanied by a comment letter, if the managers’ private benefits of going ahead with the transactions outweigh the benefits of withdrawing the deal. For example, managers bonuses are frequently linked to deal completion but not necessarily to the stock price performance (Grinstein & Hribar, Citation2004). Chinese managers’ entrenchment is also stronger than of US managers and their career outcomes less sensitive to the stock price performance (Firth et al., Citation2006; Yang et al., Citation2019).

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the effect of regulatory disclosure enforcement on M&A filings to promote more efficient decision making at the transaction announcement. The IASB and FASB identify decision usefulness as the objective of financial reporting (e.g., Gassen & Schwedler, Citation2010). Our study adds novel evidence on how enforcement of M&A filings’ disclosure and public disclosure of the action on the M&A announcement can promote this objective. In this way, we contribute to the broader literature on disclosure regulation and enforcement, surveyed in Bremser et al. (Citation1991), Cox and Thomas (Citation2009) and Leuz and Wysocki (Citation2016).Footnote34 Our study adds new insights to the literature that so far provides mixed evidence on the value of securities law enforcement.Footnote35 Importantly, our findings suggests that disclosure of comment letters provides material benefits to investors compared to delayed disclosure of comment letters such as in the US. The 20 business days reporting lag between the review completion and public disclosure of the comment letter in the US means investors do not have access to value-relevant information when they make investment decisions, such as at the M&A announcement, and the reporting lag can be exploited by corporate insiders (Dechow et al., Citation2016).

Second, we contribute to the literature examining the effects of publicly disclosed regulatory comment letters (Bozanic et al., Citation2017; Brown et al., Citation2018; Cassell et al., Citation2013; Cunningham & Leidner, Citation2021; Johnston & Petacchi, Citation2017; Robinson et al., Citation2011; Ryans, Citation2021). We extend the literature which predominantly examines comment letters on periodic filings by studying enforcement actions on M&A transactional filings and provide novel evidence on the market consequences of comment letter disclosures for such filings. Our evidence suggests that the regulatory review of all M&A filings in China increases their decision usefulness, which facilitates price-discovery. This finding can inform regulatory processes in other jurisdictions that currently do not undertake such reviews, as in the US.

Third, the study contributes to the debate on the validity of regulatory theories. The public interest theory views regulatory involvement as necessary to correct market inefficiencies (Lewis, Citation1949; Shleifer, Citation2005). In contrast, the capture theory (Grossman & Helpman, Citation1994; Pelzman, Citation1976; Posner, Citation1974; Stigler, Citation1971) predicts that regulators are ineffective, or their interests align with that of managers, e.g., because regulators vie to secure lucrative future positions at listed firms.Footnote36 Our overall conclusions challenge the view that regulatory involvement is inefficient and supports the efficacy of regulatory enforcement in the M&A setting in China.

Our findings are directly relevant for markets at similar institutional development stage as China where regulatory intervention through comment letters can facilitate price discovery, reduce information asymmetry around M&As, protect minority shareholders from expropriation, and where non-regulatory avenues for minority shareholder protection, such as litigation, are relatively weaker (e.g., Jiang et al., Citation2010). Because merger information asymmetry remains high even in developed market settings (Johnson et al., Citation2000), our results may also have broader policy implications for regulatory reviews of acquisition disclosures in jurisdictions with varying degrees of institutional and market development.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (160.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We appreciate the comments of Mark Bradshaw, Brian Bushee, Jo Horton, Zhongwei Huang, Jay Jung, Arthur Kraft, Miles Gietzmann, Clive Lennox, Maria Ogneva, Marcel Olbert, Lakshmanan Shivakumar, Ahmed Tahoun, Zheng Wang, Beatriz García Osma, two anonymous referees and seminar participants at Bayes Business School, London Business School, University of Bristol, University of Southern California, Warwick Business School, 2020 International FMA conference, 2020 CAFR conference, 2021 European Accounting Associate Annual conference for helpful comments. All errors and omissions are our own. This is first chapter of Junzi’s Ph.D. dissertation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the public sources cited in the text.

Supplemental Data and Research Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, doi:10.1080/09638180.2023.2273380.

Notes

1 See Pagliari (Citation2012), Moschella and Tsingou (Citation2013), Baker (Citation2013), Helleiner (Citation2014), Wilf (Citation2016), Cunningham and Leidner (Citation2021).

2 Our focus on the decision usefulness of disclosure enforcement actions revealed jointly with the public announcement of the filings subject to regulatory interventions differs from past research that examined how today’s disclosure enforcement actions affect future outcomes, such as quality and decision usefulness of future filings (e.g., Johnston & Petacchi, Citation2017; Cassell et al., Citation2013; Bozanic et al., Citation2017; Robinson et al., Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2018; Ryans, Citation2021). Past research does not say how the enforcement action would have affected the investigated filing’s decision usefulness for two reasons. First, the enforcement action typically happens long after the filing being investigated is made public and investors already used the filing information to make decisions. Second, decision relevance of future filings impacted by the enforcement action is likely different compared to the decision usefulness of the filing being investigated. For example, Johnston and Petacchi (Citation2017) report that after resolution of issues arisings from regulatory intervention through comment letters on 10-Q, 10-K, S-1 and other filings, future earnings response coefficients (ERCs) increase, and the adverse selection component of the bid-ask spread reduce. However, a comment letter suggests that the initial disclosure was of poor quality and should have associated with a lower ERC and higher bid-ask spreads. Thus, a comment letter issued concurrently with the commented filing signals low quality disclosure and would likely lead to different investor decisions compared to future investor decisions on future disclosures that were changed in response to that comment letter. Importantly, past US-focused research finds no evidence that regulatory effort in reviewing 10-Q and 10-K disclosures associates with significant price reactions (Dechow et al., Citation2016), however, this evidence may reflect the uniqueness of the US regulatory review process that may not extend to other jurisdictions.

3 The empirical evidence that acquisitions tend to associate with disappointing post-merger market performance is consistent with investors not discounting enough the expected benefits of some deals (Rau & Vermaelen, Citation1998; Loughran & Vijh, Citation1997; Loderer & Martin, Citation1992). Consistent with low quality disclosures obfuscating deal quality, Skaife and Wangerin (Citation2013) and McNichols and Stubben (Citation2015) discuss how low target reporting quality impedes bidder’s valuation leading to a higher range of estimates and ultimately higher offer premia.

4 E.g., the regulator asked for clarification for the 1,028% price premium Yibai pharmaceutical intended to pay for Mianyang Fulin Hospital. The bidder received a letter from the exchange asking to explain the basis for determining the price of the transaction (increase precision of filing disclosure), to provide pricing of comparable transactions in the same industry (additional disclosure absent in original filing), to provide an independent fairness opinion of the transaction’s pricing (increasing precision of filing disclosure), and to provide a discussion expected future profitability (additional disclosure absent from the filing). Managerial responses prompted by the regular can help investors to gauge if the 1,028% offer premium is fair or optimistic and the latter will associate with a negative price reaction to the merger announcement.

5 Regulators do not need inside knowledge or skill to identify low quality transactions—as long as enforcement actions are on deficient disclosures and these include more lower quality deals, comment letter prompted disclosure can benefit investors in identifying lower quality transactions. Comment letters ask for clarification of existing disclosures, which is why we believe their main effect is mediated through increasing the precision of filing disclosures, which helps investors separate lower quality deals that would otherwise pool with higher quality transactions. We do not preclude that firm responses reveal new information that can further facilitation investors in evaluating the quality of the transaction.

6 We use textual analysis to examine the letters’ content to validate that comment letters associate with substantive supplemental M&A information that can increases the amount and precision of merger disclosures. To illustrate, the regulator asks for additional pricing and valuation-related disclosures in 93.2% of letters, 92% of letters include questions about the payment method, 95.1% request more information about the target, 66% ask about the deal risk, and 85.3% about integration plan (less than 10% of mergers in our sample involve public targets, thus bidders’ filings are among key sources of information about the target. Public targets’ filings are submitted jointly with bidders’ filings to the exchange and the bidder, upon consulting with the target, is expected to respond to target’s filings comment letters). To ensure credibility, most comment letters ask that a professional accounting firm or a financial advisor certify financial opinions. The regulator can also fine the firm and individual managers for false or misleading disclosure (see Chen et al., Citation2005).

7 The regulator’s goal is to ensure decision-usefulness of M&A disclosures, not fair terms or fair deal pricing as deal terms are determined by the bidder’s negotiation with the target. Further, the regulator does not sanction potentially ‘bad deals.’ We cannot observe deals withdrawn by the bidder upon receiving a comment letter as such deals are not ultimately announced to the public.

8 Examining the market impact of enforcement reviews on M&A announcement filings is not feasible in the United States, because the SEC does not review the 8-K merger filing disclosed on the merger announcement day prior to disclosure. Filings subject to SEC review include forms S-4 if shares are issued in payment, proxy and information statements on schedules 14A and 14C, and tender offers on schedule TO, however, these filings happen weeks or months after a deal’s announcement and are dependent on the deal’s features (e.g., shares as a payment method) and path of events (e.g., a negative price reaction to the deal announcement can prompt regulatory investigation), creating timing, endogeneity and reverse causality issues.

9 The regulation on monitoring and review of acquisitions was introduced in CSRC notices, ‘Further Improving the Administrative Punishment System’ issued in April 2002 and ‘Strengthening the Construction of the Securities and Futures Legal System to Ensure the Steady and Healthy Development of the Capital Market’, in 2007. Deals exceeding 50% of the bidder’s size (captured by either total assets or revenue) are classified as a major asset restructuring and are subject to additional review focused on whether the deal is a reverse takeover (CSRC, Citation2014, Citation2016). A firm has to declare whether a deal is a reverse takeover and such a transaction needs to comply with the IPO listing rules (CSRC, Citation2020).

10 See http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/zjhpublic/zjh/200804/t20080418_14481.htm and http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/zjhpublic/zjh/201410/P020141024548321879951.pdf

11 Jiang et al. (Citation2010) highlight that tunneling and expropriation of minority shareholders is pervasive in China.

12 Less than 6% of comment letter transactions in our sample received more than one letter. We found only four cases where the firm did not respond to the comment letter and the exchange subsequently withdrew the deal.

13 The CSRC states that the suspension’s “main function is to ensure the timely and fair disclosure of information, alert investors about major risks, and maintain a fair-trading order”. Available at: http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/newsite/zjhxwfb/xwdd/201811/t20181106_346304.html

14 Investors observe the ultimate filing approved by the exchange, which can be either the original filing or, if requested by the regulator, an amended filing. Acquisition filings are not revised after the merger announcement and there are no further comment letters related to the acquisition filings issued after the acquisition announcement. Following the deal announcement, the bidder prepares a detailed Tender Offer Report with the deal conditions that is submitted to the target’s board, submits the merger control filing to the exchange, and applies for the exchange’s approval if new shares will be issued as a payment for the transaction. Bidder’s post-announcement filings are subject to regulatory review and can elicit comment letters from the exchanges. We do not study comment letters issued after merger announcements on the filings submitted after the deal is made public.

15 Cao et al. (Citation2021) highlight that social stability goals motivate Chinese regulators to use more soft-touch informal enforcement mechanisms (warnings, comment letters, supervisory talk) rather than formal measures (administrative actions) even though the latter are more efficient in correcting firm behaviour.

16 While the larger and more developed US market might seem to be an attractive setting to conduct this study, there are structural features of acquisition disclosure regulation that preclude analysis of this research question in the U.S., because acquisitions are announced prior to the submission of shareholder disclosure filings which are only subject to regulatory review after they are filed and publicly disclosed. We discuss (i) the US regulatory setting, (ii) the differences between China and the US that motivate us to focus on the former, and (iii) and past studies that examine future consequences of comment letters that our research builds on in Online Appendix I.