Abstract

This study examines how budgeting and forecasting are used in a bank that abandoned the corporate budget but later reintroduced it. Although companies that implement Beyond Budgeting may reintroduce budgets, how companies returning to traditional budgeting maintain Beyond Budgeting elements and incorporate them into the budgeting process has not been previously studied. Specifically, we address how forecasts are deployed as part of the budgeting process. The paper is based on a case study with interviews as the primary data source. We show how the interrelationships between budgets and forecasts change through three phases; before, during, and after abandonment, and illustrate how the two control elements can simultaneously replace each other for specific groups of line items and become complementary for profit planning and control. We unfold how revenue-forecasts complement cost-budgets to fulfill various budgeting purposes, especially when forward-looking tight control is emphasized to ensure outward accountability. Altogether, the study demonstrates how management control systems evolve over time when companies implement control elements with inspiration from the Beyond Budgeting model alongside budgets.

1. Introduction

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

(Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act III, Scene 1)

Particularly, the forward-looking properties of forecasting are deemed purposeful for capturing the ever-increasing environmental uncertainties (Hope & Fraser, Citation2003). While both budgets and forecasts constitute a financial plan, individuals are held responsible for budget targets, which are often negotiated in the budget process. In contrast, the forecaster is not held responsible for realizing forecasted outcomes (Anthony & Govindarajan, Citation2007). Therefore, Beyond Budgeting proponents believe that relying on forecasts in planning processes reduces the time consumption and gaming behavior traditionally caused by budgeting (Hope & Fraser, Citation2003).

However, rather than completely abandoning budgets, studies have shown that organizations generally attempt to improve budgeting by complementing budgets with the forward-looking properties of forecasts (Libby & Lindsay, Citation2010; Sivabalan et al., Citation2009). Even case studies of organizations claiming to have gone Beyond Budgeting have demonstrated that companies seem to preserve budget-like control elements as primary planning and control mechanisms (Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013; Samudrage & Beddage, Citation2018; Sandalgaard & Bukh, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019). Consequently, while budgets remain essential in most organizations, their interrelationships with other control elements may evolve when practitioners attempt to accommodate for their deficiencies.

These dynamics are often overlooked in budgeting studies. While organizations that move Beyond Budgeting constitute critical cases (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006), studies have focused on how firms implement the framework. Almost as in the famous soliloquy in Shakespeare’s work, budgeting has been discussed as a question of ‘to be or not to be,’ disregarding the possibility of travelers returning to their previous control systems, changed by the journey. Although Hope and Fraser (Citation2003) did not recall any organization wanting to return to budgeting, two case studies have indicated that firms may return from their Beyond Budgeting journey and reinstate traditional budgets (Becker, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019).

In a multiple case study, Becker (Citation2014) illustrated two out of four companies, a bank and a petrochemicals company, returning to traditional budgeting. Prior to budget abandonment, these organizations relied on fixed performance contracts for budgeting purposes, including planning, resource allocation, control, and performance evaluation. When financial downturns and changes in key personnel led to budget reintroduction, budgets were used to achieve tighter cost management and induce a sense of security. Relatedly, Valuckas (Citation2019) showed that a bank that introduced Beyond Budgeting as an alternative to centralized control started using operational plans and fixed cost targets resembling the traditional reliance on command-and-control structures. The author examined the change initiative as a ‘failed’ implementation of Beyond Budgeting and questioned whether organizations returning to budgeting really strive for adaptation and decentralization.

The studies by Becker (Citation2014) and Valuckas (Citation2019) demonstrate that firms implementing Beyond Budgeting may reintroduce budgets, but they do not address exactly what budgeting looks like after budgets are reintroduced. Reintroducing budgets may be more than a ‘failed’ Beyond Budgeting implementation and studying companies that have experienced both situations can provide new insights about how budgeting may evolve (Merchant & Otley, Citation2020). This study attempts to unfold how Beyond Budgeting inspired control elements may be combined with budgets upon their reintroduction rather than simply answering whether budgets are abandoned or not (Libby & Lindsay, Citation2010, p. 67). Specifically, we address the following research question: How and why do budgets and forecasts, and their roles and interrelationships, change over time following budget abandonment and subsequent reintroduction?

To address this research question, we study how budgets and forecasts are used in a Scandinavian bank that abandoned and reintroduced the corporate budget within a short period. Prior to abandonment, the bank already used some control principles associated with Beyond Budgeting, such as benchmarking for performance evaluation purposes. When the budget was abandoned, Beyond Budgeting inspired the change process in the bank, but the framework was not implemented as a package. Moreover, the bank returned to the budget, and we examine the budget-related processes through interviews and documents, providing empirical evidence on the evolutionary dynamics of the planning and control cycle (van der Kolk et al., Citation2020).

We mobilize the interdependency proposition (Bedford, Citation2020, pp. 3–4, Panel A) from the management control systems literature as a method theory (see Lukka & Vinnari, Citation2014) to study budgeting as a system consisting of various control elements. Emphasizing the roles and interrelationships of budgets and forecasts, we resume the call from Becker et al. (Citation2016, p. 1510) for more studies adopting a broader management control systems view to examine the fundamental control elements often emphasized in Beyond Budgeting studies.

Much research has been conducted on the role of management control systems (Merchant & Otley, Citation2020) and has debated how to best study control systems (e.g., Bedford, Citation2020; Martin, Citation2020; Pfister et al., Citation2023). For instance, Malmi and Brown (Citation2008) introduced the notion of a control package, arguing that the complete set of control elements in place should be studied, whereas Grabner and Moers (Citation2013) represented a systems view based on complementarity theory. Adopting the systems view, some studies have examined how the effect of one control element depends on the use of another and identified complementarity or substitutionFootnote1 where control elements either reinforce or diminish each other (Bedford et al., Citation2016; Grabner, Citation2014). Other studies have explored the nuances of how control elements are related (Friis et al., Citation2015; Pfister & Lukka, Citation2019; van der Kolk et al., Citation2020).

Notwithstanding, control element relationships can be perceived on a continuum between packages and systems (Demartini & Otley, Citation2020; Pfister et al., Citation2023), and various causal forms of interdependence and independence may, as shown by Bedford (Citation2020), exist. Thus, the notions of complementarity and replacement are extensible, and the dichotomous approach to studies of management control systems may be inadequate. Further, firm evolution may have ‘a distinct role to play in how we understand the level of integration of control practices for a given firm’ (Martin, Citation2020, p. 2). That is, interrelationships are dynamic, and complementary and replacing relationships may develop over time (Huber et al., Citation2013; van der Kolk et al., Citation2020).

While budgeting has received much attention in management control systems research (see Covaleski et al. (Citation2003) for a review), studies tend to apply the dichotomous systems approach to examine the complementarity between budgets as formal control mechanisms and other control elements (Bedford et al., Citation2016; Kreutzer et al., Citation2016). Still, multiple budgets and budget-like control elements may form budgetary control systems with various interdependent relationships (Bhimani et al., Citation2018). This study unfolds such dynamics by considering how various forms of complementarity and replacement evolve across budget abandonment and reintroduction periods in a unique case setting (Bedford, Citation2020).

In addressing the research question, this study makes two overall contributions. First, the study contributes to the empirical literature on Beyond Budgeting (e.g., Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013; Valuckas, Citation2019) by establishing how and why budgets are reintroduced after a period of budget abandonment, emphasizing how principles associated with Beyond Budgeting are incorporated into the budgeting system.

The study shows how a forecasting model, which was first developed to replace the corporate budget, later complemented the cost-budget when the organization reintroduced budgeting. Thus, the study nuances the Beyond Budgeting debate by demonstrating how traditional budgets remain useful for cost planning and control while forecasts inspired by Beyond Budgeting become a permanent element in the budgeting system. Budget-like control elements may be retained in organizations that move Beyond Budgeting (Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013), and conversely, Beyond Budgeting inspired control elements may become embedded in budgeting. These findings reinforce the argument for attending to management control system change processes rather than studying Beyond Budgeting as the mere abandonment of budgets.

Moreover, the budgeting literature distinguishes budgets from forecasts based on the technical nature and commitment to obtaining the goals contained in the documents (Anthony & Govindarajan, Citation2007), and case studies have found the forward-looking abilities of forecasts useful primarily for planning purposes (Henttu-Aho, Citation2018). This study demonstrates how a forecast may evolve into a budget, forming a complementary relationship because the forward-looking information generated by the forecasting model minimizes the budgetary biases traditionally produced in negotiation processes (Fisher et al., Citation2019; Walker & Johnson, Citation1999). Altogether, forecasts and budgets complement each other in fulfilling both planning, controlling, and performance evaluation purposes.

Regarding why budgets are reintroduced, the findings illustrate that undergoing a period of budget abandonment causes senior managers to realize the importance of budgets for maintaining a sense of control. However, temporarily replacing budgets with Beyond Budgeting inspired forecasts also causes a new understanding of how combining control elements can induce more forward-looking planning and control.

Second, the study contributes to the management control systems literature (e.g., Bedford, Citation2020; Merchant & Otley, Citation2020; van der Kolk, Citation2019) by establishing how the interrelationships between budgets and forecasts evolve through three temporal stages (Martin, Citation2020), namely before, during, and after budget abandonment. Delving into the budgetary control system in a unique case company, the study provides the detailed insights into management control systems dynamics warranted by accounting scholars (Merchant & Otley, Citation2020).

This study does not examine replacing and complementary relationships dichotomously. Rather, the study shows how the initial replacement of budgets with a forecasting model evolves into a simultaneously replacing and complementary relationship between a fixed cost-budget and frequently updated revenue-forecasts. During budget abandonment, the traditional reliance on tight budgetary control necessitated replacing budgets with forecasts. Other studies illustrated how complementary and replacing relationships can develop over time (Güldenpfennig et al., Citation2021; Huber et al., Citation2013), and this study contributes to the literature by showing how interrelationships are not only temporally dependent but also formed by the operationalization of line items for the specific budgeting purposes (see Sivabalan et al., Citation2009). Specifically, we show that when the budget was reintroduced, it replaced the forecast for cost items, but the statistical projections of revenues from the forecasting model became complementary to the cost-budget.

The remainder of this paper adheres to the following structure. Section 2 provides a literature review of the roles and interrelationships of budgets and forecasts presented in the budgeting and Beyond Budgeting literature. The section also introduces the management control systems literature, which can be applied as a method theory for studying budgeting. Section 3 presents the methodology, describing the case company and data collection and analysis. Section 4 delineates the findings and focuses on how Beyond Budgeting has inspired the case company to change the budgeting process, thereby developing new roles and interrelationships among control elements. Finally, Section 5 discusses the findings considering the existing literature and concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

The following sections review the literature on the properties of budgeting and forecasting when these control elements are traditionally used as fundamental parts of planning and control systems. Hereafter, we introduce the Beyond Budgeting framework as an alternative management control package and accentuate the tensions regarding the roles and interrelationships between budgets and forecasts in the existing literature. The final sections consider the literature on management control systems, firstly introducing the existing notions in the systems versus package debate and then unfolding the complexities of control element interrelationships and temporalities.

2.1. The Budgeting System

Budgeting is a highly formalized control system implemented to improve decision-making and ensure effective financial management, also under uncertainty (Marginson & Ogden, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). Budgets are most often related to other control elements, and several authors argue that the budget should not be studied as an isolated control element, but rather as part of a budgetary control system (Grabner & Moers, Citation2013; Malmi & Brown, Citation2008; Pfister et al., Citation2023). The interrelationships between budgeting and other control elements can be configured in various ways, and multiple budgets and budget-like control elements may be configured as a budgetary system with interdependent and independent relationships (Bhimani et al., Citation2018).

Sivabalan et al. (Citation2009) stated that the three primary budgeting purposes, which are temporally connected in the budget cycle, are planning, control, and performance evaluation. Planning includes setting ambitious yet realistic budget targets and coordinating organizational efforts. Within the budget cycle, variances between targets and actuals are analyzed to ensure control. Finally, performance is evaluated in relation to budget targets (Sponem & Lambert, Citation2016). When budgetary control is tightened to enforce budget achievement and increase accountability (Sinclair, Citation1995), superiors lower their tolerance for budget variances, follow up on more detailed line items, and increase discussions of performance in relation to budget goal attainment (Van der Stede, Citation2001). Similarly, organizations may pay attention to accountability towards external stakeholders such as shareholders, analysts, and regulators and create changes in the budgeting systems to reinforce outward accountability (Stockenstrand, Citation2017). Consequently, providing information to external stakeholders, such as earnings guidance, may become a budgeting purpose (Sivabalan et al., Citation2009, p. 854).

The budgeting literature demonstrates how contradictory incentives can lead to budgetary biases, implying systematic differences between the most likely future outcomes and the information contained in the budget (Fisher et al., Citation2019; Walker & Johnson, Citation1999). Such biases impact the fulfillment of budgeting purposes within and across budget cycles. Some studies show how forecasting can be implemented to solve the budget-related tensions; from the budget process itself and from using budgets for conflicting purposes (Bhimani et al., Citation2018; Palermo, Citation2018).

Contrary to budgets, forecasts are not necessarily approved by superiors because they are considered a projection of the future, and the forecaster is not held responsible for realizing forecasted outcomes (Anthony & Govindarajan, Citation2007). Still, forecasts can be established through negotiation, and accuracy is accentuated as a measure of quality (Jordan & Messner, Citation2020). While budgets are often implicitly assumed to follow an annual budget cycle, forecasting cycles can be both shorter and longer. Forecasts can also be rolling in the sense that they are updated on a regular basis, typically every month or quarter, as a new period is added, while the oldest period is dropped (Hansen, Citation2011).

Generally, studies find that rolling forecasts cannot replace budgets (Henttu-Aho, Citation2018; Sivabalan et al., Citation2009). Instead, these control elements work complementarily to budgets to fulfill budgeting purposes over different time horizons (Henttu-Aho, Citation2018). Consequently, many organizations use the objectivity and forward-looking abilities of forecasting to improve planning, while budgets continue to be the primary mechanism for establishing and evaluating ambitious targets (Palermo, Citation2018).

2.2. Beyond Budgeting

A particular stream of literature oriented toward practitioners argues in favor of budget abandonment and indicates that other controls should be used instead, asserting that this is the only way to reduce budget-related tensions, inhibit dysfunctional behavior, minimize resource consumption, and account for the rapidly changing business environment (Bogsnes, Citation2016; Hope & Fraser, Citation2003). The fundamental idea of Beyond Budgeting is that budgets should be abandoned entirely as a prerequisite for improving the management control package through adaptive processes and radical decentralization (Hope & Fraser, Citation2003). However, it has been argued that the idealistic nature and lack of pragmatism in the Beyond Budgeting model may inhibit the implementation of control elements as a package (Becker et al., Citation2020) even though many companies have used it as a source of inspiration for budgeting improvement (Becker, Citation2014; Matějka et al., Citation2021).

Case studies have examined how and why Beyond Budgeting implementation transpires in practice and how it impacts the roles and interrelationships of control elements. O’Grady and Akroyd (Citation2016) demonstrated how an organization formally replaces budgets with a Beyond Budgeting control package, including decentralized empowerment, relative goals, and dynamic resource allocation. Bourmistrov and Kaarbøe (Citation2013) illustrated how the need for outward accountability induces organizations to replace fixed budget goals with outside-in targets based on performance relative to competitors. Further, some case studies have specified that decoupling budgeting purposes from the traditional budget cycle is instrumental for Beyond Budgeting implementation (Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013; Østergren & Stensaker, Citation2011). Such studies have shown how organizations replace budgets with rolling forecasts for planning and external benchmarks for performance evaluation in two temporally separated processes.

However, as Valuckas (Citation2019) remarked, the majority of the empirical literature on Beyond Budgeting implementation emphasizes the gradual development of budgeting processes and elements rather than the instantaneous or complete abandonment of budgeting. Although Beyond Budgeting proponents advocated for decentralization of decision-making (Hope & Fraser, Citation2003), case studies have shown that organizations may increase the use of top-down target setting, reinforcing upward accountability (Østergren & Stensaker, Citation2011; Sandalgaard & Bukh, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019). Further, sales-oriented forecasts may be used to identify gaps between goals and projected results to refine action plans (Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013). Some case studies have indicated that budget-like control elements, such as ‘frozen forecasts,’ ‘annual plans’ (Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013), or ‘financial forecasts’ (Valuckas, Citation2019) replace budgets when Beyond Budgeting is implemented. Organizations thus continue employing mechanisms that resemble the traditional use of budgets (Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Valuckas, Citation2019).

The empirical Beyond Budgeting literature provides possible explanations for the need to preserve the budgeting system. Sandalgaard and Bukh (Citation2014), for example, stated that a lack of comparability between business units makes internal benchmarking ineffective. Another study has established that the inability to obtain information from competitors, such as in the apparel industry, where only a few firms are listed, limits the use of external benchmarking (Samudrage & Beddage, Citation2018, p. 121). Therefore, organizations may merely use Beyond Budgeting as an inspiration to simplify the budget process and complement budgets or budget-like control elements.

In a multiple case study, Becker (Citation2014) identified several reasons why organizations may reinstitutionalize budgets after a period of abandonment when theorizing budgeting as an institutionalized practice. The study discovered that companies emphasize the role of the budget in providing fixed targets and controlling costs and reintroduce budgets for these purposes in times of crisis. In a single case study, Valuckas (Citation2019) accentuated the absence of organizational support as the primary reason for budget reintroduction. As in the case companies in Becker’s (Citation2014) study, senior managers’ habitual reliance on budgets to induce certainty led to a ‘failed’ change initiative where Beyond Budgeting never got institutionalized (Valuckas, Citation2019).

Although the empirical literature provides numerous insights into Beyond Budgeting implementation processes and explanations for why organizations may continue to use control elements in a budget-like manner or reinstate budgets after a period of abandonment, no studies have yet addressed exactly how the management control system is developed after budgets have been reintroduced (Matějka et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Management Control Systems

According to Lukka and Vinnari (Citation2014), a domain theory is a particular set of knowledge about a domain. In this paper, we study budgeting as a domain by examining its interrelationships with forecasting (Henttu-Aho, Citation2018; Sivabalan et al., Citation2009). Relatedly, a method theory is a theoretical lens that can be applied to a domain theory to provide alternative perspectives (Lukka & Vinnari, Citation2014). In this paper, we mobilize the interdependency proposition from the management control systems literature (Bedford, Citation2020). This provides a vocabulary and conceptualization that enables studying budgeting as a control system, consisting of different control elements, including budgets and forecasts.

Initially, Anthony (Citation1965) defined planning and control as the primary purposes of management control systems. Following Anthony's seminal work, various approaches have been used to examine management control systems in practice (Merchant & Otley, Citation2020). Some authors focus on control packages (Malmi & Brown, Citation2008), while others consider only interdependent control systems. Inspired by complementarity theory (Milgrom & Roberts, Citation1995), the systems approach describes how interdependence among control elements can occur as complementarity or replacement (Grabner & Moers, Citation2013). According to this dichotomous viewpoint (Demartini & Otley, Citation2020, p. 1), complementarity exists when one management control element improves the effectiveness of another, whereas replacement occurs when one control element decreases the effectiveness of another.

Several studies have been conducted to quantitatively investigate control element combinations within a single control system (Grabner, Citation2014; Grabner & Moers, Citation2021). Kreutzer et al. (Citation2016) found that the use of formal controls, such as budgets, complements informal controls in team performance. Further, Bedford et al. (Citation2016) illustrated how diagnostic or interactive budgets become complementary or replacing to different organizational structures depending on firm strategy.

Unfolding how control packages often consist of both control elements and control systems, Bedford (Citation2020) presented various causal forms of complementarity and replacement. The proposition of interdependency delineates the mechanisms through which control element interrelationships may arise and impact the effectiveness of management control systems.

Compensating, reinforcing, and enabling forms may create complementarity (Bedford, Citation2020). Control elements compensate for each other when one element counterbalances the limitations of another, they reinforce each other when one element enhances the properties of another, and they are enabling when the presence of one element conditions the control problem-solving abilities of another. In the budgeting domain, a compensating form of complementarity may exist between budgets and rolling forecasts, as forecasts counterbalance predictive limitations by providing a frequently updated forward-looking perspective (Sivabalan et al., Citation2009).

Inhibiting, exacerbating, instigating, and interchangeable forms can lead to replacement (Bedford, Citation2020). Control elements inhibit each other when one control element hinders the abilities of another, they exacerbate each other when one control element increases the detrimental impact of another, and they are instigating when the presence of one control element creates conditions that negatively affect the problem-solving abilities of another. Finally, interchangeable control elements can replace each other without changing the overall effectiveness of the system. In the budgeting domain, the effort-increasing effect of establishing difficult targets may be diminished by incentive systems that do not weigh these targets in determining bonuses, causing an inhibiting form of replacement (Matějka & Ray, Citation2017). However, as pointed out by van der Kolk et al. (Citation2020), replacement may not necessarily lead to the disappearance of a control element.

Some qualitative studies have been conducted to explore the interrelationships between control elements in depth (Friis et al., Citation2015; Güldenpfennig et al., Citation2021; Pfister & Lukka, Citation2019). Friis et al. (Citation2015) illustrated the importance of examining the relations between specific rather than aggregated control elements. For instance, administrative control comprises both job design and job rotation, and simply examining the interrelationships with other control elements on the aggregated level would yield imprecise results. Berg and Madsen (Citation2020) found that the educational background of leading controlling personnel changes the use of budgets from interactive to diagnostic. Similarly, Toldbod and van der Kolk (Citation2022) demonstrated how the need to centralize planning and control after a financial crisis has cascading effects on the rest of the management control system. Still, these evolution studies only describe how individual control elements change over time and do not attend to the development of interrelationships.

Huber et al. (Citation2013) delved into the dynamics of the interrelationships between contractual and relational governance in a case study and unfolded how these control elements can become complementary and replacing during different stages of development projects. By illustrating how the relationship can shift from favorable to adverse over time, the authors provided a possible explanation for contradictory findings in the literature regarding these control elements. When examining multiple management control systems Güldenpfennig et al. (Citation2021) also found both complementary and replacing relationships.

Following how these studies expand the notions of complementarity and replacement, we seek to investigate how budgeting, as a control system, changes when Beyond Budgeting inspired control elements are combined with traditional budgets. Despite examples of studies that demonstrate different causal forms of complementarity and replacement, the literature remains scarce in examining how these interrelationships evolve dynamically (Martin, Citation2020). Studying budgeting change processes, we enrich the management control systems literature (Merchant & Otley, Citation2020, p. 5) and convey how interrelationships emerge conditioned by past decisions regarding the use or lack of budgets (Bedford, Citation2020, p. 7).

3. Research Setting and Methods

3.1. Research Setting

The case company, BankCorp (name disguised), is a listed Scandinavian bank that offers a broad range of financial services, including loans, pensions, and insurance services, based on serving retail customers and small and medium-sized enterprises through personal relationships. The bank has been involved in several mergers and acquisitions and is currently one of the largest banks in the country where it operates. BankCorp has a diversified lending portfolio and a persistently strong credit quality throughout the business cycle. In recent years, the bank has recorded one of the highest returns on equity among the large banks in the country of operations. The business model is based on decentralized decision-making, empowering managers and frontline employees. Nevertheless, BankCorp is centralized with respect to its lending policy and decisions that influence risk-taking.

BankCorp was chosen for the study because one of the authors had insights into the budgeting process and was aware that the company, despite traditionally relying on budgets for various purposes, including earnings forecasts in financial reporting, had altered the management control system with inspiration from Beyond Budgeting a few years before the study. Following a restructuring of the data warehouse, which left BankCorp with no available budget data, the bank formally erased the word ‘budget’ from its written policies. After having operated without a corporate budget for about one year, the budget was reintroduced. This allowed examining how budgeting was configured and perceived before and during budget abandonment and after re-employment.

The banking sector is characterized by a high level of uncertainty, and a dynamic environment has been identified as a central argument for abandoning budgets (Sandalgaard & Bukh, Citation2014). Some factors, such as loan impairments, income from fees, charges, and commissions, interest margins, and market-value adjustments, are highly dependent on macroeconomic factors. Still, corporate decisions about the lending policy, interest rates, and fee structure influence financial results. Even though core earnings are relatively stable in the short term and can be projected with reasonable precision, the annual budget may be insufficient to capture the external circumstances that heavily influence banking operations. Additionally, the literature emphasizes that the branch-based structure of retail banks allows the implementation of internal benchmarking as an alternative control mechanism (e.g., Cäker & Siverbo, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019).

Beyond Budgeting case studies sometimes focus on how principles are implemented as a control package (e.g., O’Grady & Akroyd, Citation2016), but many of the proposed control elements, such as decentralized decision-making and internal benchmarking, were already present in BankCorp when the company decided to adopt certain Beyond Budgeting principles. Consequently, the Beyond Budgeting framework was not implemented as an entirely new management control package. The study of BankCorp focused on how the Beyond Budgeting initiative changed the interrelationships between budgets and new control elements after the reintroduction of the budget. The formal abandonment and subsequent reinstatement make the bank a critical case (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006). That is, the research setting was chosen to increase the chance of making contributions to theory through case study empirics (Ahrens & Chapman, Citation2006).

3.2. Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and documents related to the budgeting process. Some documents, like annual and quarterly reports, were publicly available on the company webpage, whereas other documents were shared with us by the people we interviewed. We gained access to different detailed reports prepared for executives and branch management, including written instructions regarding budgeting and forecasting, quarterly and monthly follow-up reports, and external benchmark reports. The interviewees provided documents concerning the periods before, during, and after the budget was abandoned, and all documents underwent actuarial readings (Garfinkel, Citation1967). The documents gave insight into details, such as wording and layout, that had been recorded systematically by the case company. We considered the documents important sources of information, as they allowed us to reconstruct information about past events.

We interviewed managers and employees from various back-office departments, including accounting, internal auditing, and risk management, as well as branch managers and frontline employees. Further, two non-executive Board members were interviewed. provides an overview of the interviewees.

Table 1. Overview of interviewees

All interviewees were chosen due to their longstanding involvement in the budgeting process, which allowed us to consider events from different perspectives (Saunders & Townsend, Citation2018). Most interviewees had been employed with the case company for several years; hence, they had experienced the period before, during, and after budget abandonment, making it possible to study budgeting longitudinally through retrospective interpretations (Langley, Citation1999). In total, 25 people were interviewed, and each interview lasted between half an hour and one and a half hours. The semi-structured interview guide was structured around broad themes (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2014), commencing with introductory questions about the interviewee, followed by general questions about the strategic situation of the case company. Subsequently, questions about the management control system and, finally, questions concerning the budget-related processes, purposes, and uses were asked. Due to the differences in the interviewees’ experience with and involvement in the budgeting process, the interviewer paid attention to the themes and questions most relevant in each interview. Furthermore, following Ferreira and Merchant (Citation1992), we refined the interview guide continuously to incorporate newly available data. All interviews took place at the interviewee’s respective workplace, and we ensured all participants anonymity.

3.3. Data Analysis

All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed, preserving all the data as written documents. The interviews were carefully coded in relation to the literature review (Saldaña, Citation2016), and while the initial coding was done using broad, descriptive codes, inferential codes were subsequently developed (Berg, Citation2017). We started by focusing on broad categories related to the budgeting process, identifying control elements such as ‘annual budget,’ ‘forecasting,’ and ‘internal benchmarking’ to establish the characteristics and purposes of individual elements. Hereafter, we based the coding on the chronological structure of the changes experienced by the case company to understand the development of the interrelationships between budget-related control elements.

Specifically, during the coding process, we noted that the Beyond Budgeting initiative had altered the interrelationship between forecasts and the budget. Thus, a final coding round was performed to thoroughly understand these two control elements and their interrelationships in relation to the domain theory. Further, to ensure that we analyzed the interviews in connection to the management control systems literature, we considered the research setting (Grabner & Moers, Citation2013, pp. 414–417). Because budgeting appeared as a system of interrelated control elements used to solve the same control problem, namely fulfilling budgeting purposes, we found it appropriate to code our data using specific theoretical definitions from the interdependency perspective (e.g., ‘complementarity,’ ‘replacement,’ and their causal forms) (Bedford, Citation2020). We attended to how the interrelationships between budgets and forecasts emerged and coded the different forms of complementarity and replacement based on perceptions about their roles and effectiveness in fulfilling budgeting purposes.

As a result, the coded data resulted from a mixture of predefined and free codes derived from empirics (Berg, Citation2017), allowing us to answer the research question meaningfully by reinforcing general opinions from the transcripts with specific quotes (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2014). As suggested by McKinnon (Citation1988), validity was ensured using quotations in the analysis and having interviewees accept the interpretations and translations. Further, we validated data from the semi-structured interviews by cross-examining them with external and internal documents (Eisenhardt, Citation1989).

4. Findings

The following sections chronologically present how budgeting developed in BankCorp, and how a Beyond Budgeting inspired initiative changed the roles and interrelationships between budgets and forecasts. The budgeting system is configured on multiple organizational levels (van der Kolk et al., Citation2020), but we center the analysis around the corporate budget used for planning, control, and performance evaluation purposes by the Board of Directors. That is, we focus primarily on the relations between the Board, executives, and capital markets.

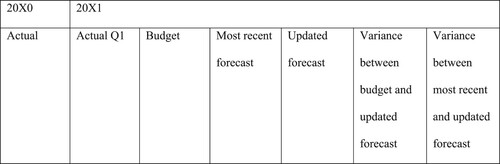

First, the traditional design of the budgeting process is briefly presented to demonstrate how the bank initially relied on tight budgetary control, emphasizing how the perceived importance of budgets affected the subsequent design choices. Second, the period of budget abandonment is described, delineating how the forecasting model was developed as a control element to replace the corporate budget. Finally, we explain how the formal reintroduction of budgets resulted in a complementary relationship between budgets and forecasts. provides an overview of the roles of the control elements during the three phases, emphasizing internal planning and controlling purposes along three dimensions, namely revenue, cost, and profit line items as well as external provision of market guidance at the beginning of the fiscal year and in reports during the year. Hence, the table shows how the interrelationships between budgets and forecasts change to fulfill these purposes.

Table 2. The roles of control elements in the planning and control cycle during the three stages

4.1. Before Budget Abandonment – a Tight Budgeting Process

Before initiating the Beyond Budgeting inspired changes to the budgeting principles in 2016, BankCorp was operating a traditional budgeting process, emphasizing tight budgetary control (Van der Stede, Citation2001). From a corporate perspective, the budget served as the primary planning and control mechanism with detailed follow-ups on aggregated line items, analyses of budget variances, and corrective actions taken to ensure budget goal attainment. The budget resulted from an aggregation of branch budgets, which consisted of cost-budgets based on traditional line-item budgeting, financial key indicators (e.g., cost-to-income ratio, return on equity, and net interest margin), and non-financial performance measures regarding, for example, customer and employee satisfaction and sales.

The tightness of budgetary control was differentiated across line items. Cost items were considered highly controllable, while credit losses and revenue items were regarded as less controllable in the short term, as they were highly dependent on macroeconomic factors, competition in the sector, and general market conditions. However, tight budgetary control based on monthly variance analyses was important because adherence to legislative liquidity and solvency requirements was interlinked with budgets, and because stock market announcements, including disclosure of forward-looking information, were based on the corporate budget. In this way, the budget complemented the corporate financial targets disclosed to the stock market, as shown in the first column of .

In the wake of the financial crisis, monetary or stock-based incentive schemes were no longer used. Still, the executives were committed to attaining the corporate targets in accordance with demands for outward accountability (Stockenstrand, Citation2017). To prevent external shocks from endangering the macroeconomic stability provided by the financial sector, the authorities increased the capital requirement for banks, enforcing capital buffers to be established. Moreover, the management control system became increasingly integrated with earnings guidance in financial reporting. Control elements were developed to ensure internal planning and control and render possible detailed reporting and compliance with legislative requirements. An executive described how the increasing outward accountability reinforced the practicality of tight budgetary control, saying ‘the budget we have made, that is what we use to control the bank … and that is what we communicate to the market’ (Interviewee 24).

4.2. Budget Abandonment – Beyond Budgeting as an Inspiration for Change

4.2.1. Formal budget abandonment

In 2014, BankCorp decided on a major data restructuring and implementation of a new data warehouse. Following IT development projects in 2015 toward the actual implementation of the data warehouse in 2016, changes to the management control system were also initiated. In developing the data warehouse, the accounting department realized that the new data structure would inhibit the possibility of establishing a traditional budget for 2017, as no reliable accounting data were available. Therefore, the accounting department considered the data warehouse restructuring an opportunity to reconfigure the budgeting process using ideas from Beyond Budgeting.

The accounting department had been interested in Beyond Budgeting for some time. The Chief Financial Officer explained that they ‘had debated it, to say the least, a few times up until 2016 … whether to abandon the budgets’ (Interviewee 10). Further, the business controllers were aware that ‘Svenska Handelsbanken has done this quite many years, and we were a bit inspired by them back in 2016 and 2017’ (Interviewee 3) since this Scandinavian bank ‘had allegedly been successful in doing so’ (Interviewee 2). The former Head of Accounting had noticed that ‘[BankCorp] should be ideal for a Beyond Budgeting model … we want decentralized control, we let go and such things’ (Interviewee 4), but BankCorp did not intentionally replicate Svenska Handelsbanken’s implementation. Rather, the changes in the IT systems created a window of opportunity. A business controller recalled:

Concerning our change … a window for trying this out emerges. Because you did not really have anything to control by, right … You did not have any valid data at the time. And then we actually suggested to like try … To do this. (Interviewee 2)

After carefully examining the legislation and regulatory demands, the accounting department reported to the Board of Directors that the requirement of a financial plan was not contingent on the use of budgets. Consequently, they approved the discontinuation of the corporate budget, and in June 2016, the term ‘budget’ was literally erased from the formal written policies in BankCorp. For instance, the sentence stating that the Board should ‘review and approve the corporate budget’ by signing the document was removed from the written instructions, delegating formal decision-making authority from the Board to executives. Additionally, neither branches nor back-office departments formally prepared budgets. Instead, a simple cost projection was made for expected staffing based on historical data.

4.2.2. Replacing control elements

Budgets used to be a critical element for planning and monitoring financial key ratios related to regulatory purposes. Thus, the management control system needed to be redesigned to achieve the same objectives at the corporate level. As stated by the former Head of Accounting, it was decided to improve forecasting, ‘very much in relation to these Beyond Budgeting techniques’ (Interviewee 4). The Chief Financial Officer explained:

… we also had to make that during those years, a budget, a forecast, because we, as a listed bank, have to guide the market about our expected income. (Interviewee 10)

Even though the forecasts were updated quarterly, they were not rolling with a constant look forward on, for example, 12 or 18 months, as in other case studies of Beyond Budgeting implementation (Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013; Valuckas, Citation2019). The Head of Accounting stated, ‘It is not like we roll 12 months ahead, we do not do that’ (Interviewee 1). Rather, the fiscal year was in focus, implying a planning horizon of 12, 9, 6, and 3 months. A financial employee at the sales and chain office said, ‘At one point, we used rolling budgets; it was hell because then the budget rolled all the time, which was difficult to explain to the Board of Directors’ (Interviewee 9), accentuating the importance of a static planning period. Moreover, the Board of Directors continued emphasizing variances between forecasts and actuals and following up on aggregated line items. The forecasting model provided a statistically projected basis for planning, controlling, and performance evaluation, as delineated by the second column in , but in practice, the use reproduced the tight revenue and cost control traditionally enforced through budgets (Sinclair, Citation1995).

4.2.3. The forecasting model: an improvement to the management control system?

Although the choice to abandon budgets was more a matter of ‘the database than a change in principles’ (Interviewee 3), it had broader implications, as explained by a business controller. The former Head of Accounting reflected on how:

… we need to have numbers, we need to have a contract, we cannot just say that ‘now you have to run further’ … The uncertainty that Beyond Budgeting creates is actually quite rough … You may say that it is freedom, but freedom also creates the possibility that you may choose 100 things wrongfully. (Interviewee 4)

… almost every year, the Chief Executive Officer said, ‘I do not want to do it anymore, I do not want to establish these budgets, it takes too much time, and they are not worth anything’ because we have already made a new forecast. (Interviewee 4)

… the more dynamic [an environment] you are in, the more it speaks to not having budgets. Because what do you need them for . .. when we are done in January, our budgets are at worst three months old (Interviewee 3).

Also, the Board of Directors immediately favored the model when they learned how it could replace the budget. A Board member expressed, ‘I definitely thought the forecast was the best. And I found, when we used it, that we were more updated [on forecasts] than we were on the budgets’ (Interviewee 21). Other Board members elaborated on the effectiveness of forecasts, as they were reassessed quarterly and evaluated discretionary actions rather than adhering strictly to budget goals, which they believed allowed for more flexible follow-ups.

Beyond Budgeting proponents (Hope & Fraser, Citation2003) emphasized that budget abandonment is a prerequisite for developing more adaptive processes and radical decentralization. Further, case studies have shown that specific control elements, such as benchmarking (e.g., Østergren & Stensaker, Citation2011), are part of the Beyond Budgeting management control package. BankCorp did not introduce specific techniques besides developing the forecasting model when abandoning budgets, since the existing decentralized branch-based structure already devolved substantial decision-making authority to branch managers, and benchmarking mechanisms were already in place (as described in section 3.1).

Moreover, the motivation to abandon budgets was more the lack of reliable budget data following IT developments than a deliberate wish to go Beyond Budgeting. The former Head of Accounting stated that ‘I subscribe to that type of freedom … Why not just look at customer satisfaction and a few key financial indicators … You can call it Beyond Budgeting, or you can call it simplified budgeting, or something’ (Interviewee 4), suggesting that the accounting department did not regard the forecasts as part of an entirely new control system. The Beyond Budgeting package described by Hope and Fraser (Citation2003) was thus not implemented as such, but the principles served as an inspiration for improvement.

4.3. Budget Reintroduction – the New Role of Forecasting in Budgeting

4.3.1. Returning to the budget

As also shown in other case studies of banks that discontinue the use of budgets (Becker, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019), BankCorp returned to budgeting after a while. In 2017, the corporate budget was reintroduced as a formal control system. Initially, the accounting department felt enthusiastic about minimizing resource consumption and reducing tensions between budgets and disclosed corporate targets. However, according to a Board member, ‘implementation, in my world, that is when you have adopted it, and you have thought “oh, I can do this, we will give it a try”’ (Interviewee 19). Elaborating on this, the Board member explained how control elements must be considered meaningful to people in the organization to be appropriately implemented. A business controller furthered the argument:

It may be too narrow to see operating without budgets as something an accounting department does. One thing is that the executives and management must have, lead the way and show the way and think that it is a good idea … Another thing is that you anchor it in the organization and that it is not just the accounting department that believes it is a good idea … So, I think we could have missed something in that part of it. (Interviewee 2)

When the forecasting model was integrated into the existing planning and control system, most people involved in the budget-related processes realized there was no point in distinguishing the term budget from the forecast in the company policies. A business controller explained that ‘the argument for doing it in the first place was the lack of data from the data provider, so it was not motivated by a wish to control without budgets … It was not too difficult to return’ (Interviewee 2). As a result, the completion of the data warehouse restructuring reintroduced the possibility of creating budgets, which was an immediate reason for reintroducing the term ‘budget.’ Furthermore, in accordance with Marginson and Ogden's (Citation2005b) proposals, it was discovered that budgetary information was critical for many reporting and control processes, particularly those involving operational uncertainty and cost control.

4.3.2. The new roles of budgetary control elements

Although the corporate budget was restored, it was given a new role following BankCorp's budget abandonment period. In contrast to other studies that investigated the complementary relationship between budgets and rolling forecasts (Palermo, Citation2018; Sivabalan et al., Citation2009), the forecasting model was not only regarded as an improvement to planning but was also integrated with controlling and performance evaluation. As a result, the forecasts were given more weight than the budgets, especially for planning and controlling revenues.

A business controller said, ‘We have started focusing noticeably more on those [forecasts] … because we have this requirement … to report, early warnings, we have to publish immediately’ (Interviewee 3). Thus, the forecasting model was also used ad hoc as calculative decision support, enabling BankCorp to comply with the market abuse regulation and disclose financial information as soon as forecasted outcomes differed from the previously disclosed expectations (Nordberg & Stockenstrand, Citation2017, pp. 90–93). The Head of Accounting affirmed the importance of financial reporting, as ‘previously we have always gone to the public and made this upward or downward adjustment … when it had been approved at the Board meeting, but we cannot wait for that now. We must [report] immediately if we deviate’ (Interviewee 1). Therefore, the frequently updated forecasts were considered to enhance the timeliness of disclosing financial information. A Board member elaborated:

… in the beginning … when we guide the coming year, it is based on the budget … later, it is based on the forecast … typically, we get more and more precise, the [guidance] interval gets smaller and smaller. (Interviewee 22)

According to the former Head of Accounting, ‘part of this budgeting process, it is to create this … contract, or whatever we call it, with the Board’ (Interviewee 4). That is, the executives were not only responsible for satisfying external demands, but they were also held accountable by the Board of Directors, and ‘in that sense, it is used to control us … but it is the same that is reported to the market … it is two sides of the same coin’ (Interviewee 24), as expressed by an executive. Usually, the conflicting demands for realistic corporate target-setting and challenging branch-level goals led to lengthy budget negotiations. The former Head of Accounting described how forecasts would be useful in establishing dual upward and outward accountability on a corporate level:

Generally, I would rather that we just made an effort to analyze on the corporate level. Because we need a corporate forecast … that we can take to the Board of Directors, that we can take to the outside world and say that this is the way we go. (Interviewee 4)

4.3.3. Budgeting costs and forecasting revenue

The former Head of Accounting distinguished forecasting from budgeting, asserting that ‘there is quite a big difference whether you make a budget, or you make a forecast’ (Interviewee 4), potentially because the corporate budget was, before the budget abandonment period, aggregated from branch and back-office budgets. In contrast, the forecasts were now based on statistical model projections.

The former Head of Accounting briefly stated, ‘We have typically forecasted the last three months of this year. And then budgeted 12 months next year’ (Interviewee 4). The statistically projected forecasts were used during the year to identify gaps between forecasted outcomes and corporate targets to establish whether the budget should be revised in the planning process. While the forecasting model was updated each quarter, a forecast detailing revenue and cost items for the subsequent year, the fiscal year, was turned into a corporate cost-budget by the end of the third quarter.

The cost-budget was fixed for the fiscal year once settled, as stressed by a financial employee at the sales and chain office who said that ‘once we have finalized the budget, the budget is locked’ (Interviewee 9). However, the revenue-forecast frozen (Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013, pp. 8–9) for the fiscal year was only deemed relevant for planning until quarterly updated forecasts became available. The business controller responsible for establishing forecasts elaborated:

… month after month, we update it with realized numbers in the one we had forecasted, where I can follow up on how far away, we have been on individual elements. Then it projects the rest automatically … So, our forecasting model and budget model melt together. (Interviewee 3)

The Head of Accounting explained that BankCorp made a ‘budget on costs and then more forecasts on revenue’ (Interviewee 1), accentuating the complementary interrelationship of the fixed cost-budget and the revenue-forecasts (Bedford, Citation2020), which is shown by the third column of . Characterizing the banking sector as generally having only a few major cost categories (e.g., employee costs) controllable at a branch level, the Chairman of the Board recognized that ‘you cannot rescue a bank by saving your way through it’ (Interviewee 23). Therefore, the financial plan contained a cost-budget, which served as a reference point during the year since it was acknowledged that ‘it is natural that you consider, if you are challenged, whether some costs can be reduced … every year it is part of the budget process’ (Interviewee 23). The executives were held accountable for costs based on the budget, but at the corporate level, major cost categories would not be decided without formal approval from the Board of Directors. Tightly monitoring corporate costs, the Board gave increasing attention to revenue-forecasts in their follow-ups. A business controller stated:

I will say that at the moment the Board of Directors has approved it, and we begin rolling, then I also believe that the Board does not care … they look less at the budget because now they look more at forecasts. (Interviewee 3)

The Chairman of the Board expressed, ‘The interesting part is seeing how it looks the next months … if I have to weigh it, it is 2/3 forward-looking [on forecasts] and 1/3 looking back [on budgets]’ (Interviewee 23). Thus, as explained by another Board member, the forecasts remained part of ‘the job of controlling the work of the executives’ (Interviewee 20). Both the cost-budget and the revenue-forecast had to be formally approved by the Board of Directors. Even though they acknowledged that the budget provided the opportunity ‘that you generally can have a view on what … they are supposed to contribute with’ (Interviewee 19), the Board members were also aware that potential periodization and controllability issues arising from relying solely on a fixed annual budget could undermine personal accountability. A Board member stated:

I believe it is a misunderstanding that this gives a sense of responsibility. You do not care about that because you do not have any influence. (Interviewee 19)

Consequently, the management control system was developed, and a combination of control elements was utilized, as the follow-ups became more concerned with evaluating executives’ decision-making based on financial information from various sources. ‘Of course, they control us based on the updated forecasts because we actually spend quite a lot of time on them,’ an executive explained (Interviewee 25).

The Board of Directors evaluated the bottom line from the financial plan in their quarterly follow-ups, taking into account both revenue-forecasts and the fixed cost-budget. Traditional variances between budgets and actuals were no longer emphasized. Instead, the quarterly reports contained information about variances between budgets and forecasts, as shown in . In essence, the organization went beyond traditional budget variances.

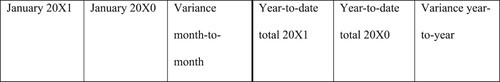

Furthermore, monthly follow-up reports were used to ensure internal control over profits. These reports were not directly aligned with financial reporting, as not all items were accrued, but they were important to motivate continuous improvement and operational stability. Every month, the Board was presented with actual results, which were compared with the same month in the previous year. provides an illustration of monthly reporting. Further, the monthly reports entailed comparing year-to-date performance between the current and past fiscal year. The monthly reports showed the analyses on overall line items and financial key indicators, providing the Board with written explanations about changes in comparison to the previous year.

Finally, an external benchmark report was presented to the Board of Directors biannually to show how BankCorp performed on financial key indicators compared to similar banks. For the bank to have a competitive strength concerning acquisition possibilities, how the bank performed on financial ratios, such as cost-to-income, compared to its peers was critical, as this also influenced the relative valuation of the bank at the stock market (Armstrong et al., Citation2016, p. 121). Thus, the bank needed to not only realize corporate targets but also pay attention to its ranking among competitors. The Head of Accounting pointed out the following:

We make this biannual benchmark report where we benchmark the entire bank, BankCorp, against [competitors]. We make some key measures concerning how we are placed … compared to them. And analyze a bit how we differentiate ourselves positively or negatively compared to them. So, we do that on a corporate level. (Interviewee 1)

4.4. Lessons from the Journey

Although the Beyond Budgeting initiative did not lead to a prolonged abandonment of budgets in BankCorp, changes in the organizational context caused by the implementation of the new IT system had an impact on the design of the management control system (Martin, Citation2020), and new interrelationships emerged between forecasts and budgets after budgets were reintroduced.

When the data warehouse restructuring hampered the traditional reliance on tight budgetary control, the forecasting model was established to replace it, and the control elements were considered interchangeable because the forecasts could fulfill budgeting purposes as effectively as budgets (Bedford, Citation2020). Despite concerns about uncertainty, the accounting department found inspiration in the Beyond Budgeting framework. When the Board of Directors began engaging with forecasts during the planning and control cycle, they noticed the forecasts’ dynamic and forward-looking capabilities, particularly for ensuring outward accountability.

As a result, while budgets were reinstated, techniques from the budget-less period were retained. On a corporate level, the financial plan evolved from statistical projections generated by the forecasting model, which reduced time consumption while increasing information accuracy. The forecasting model became complementary to developing the budget based on its technically enabling abilities (Bedford, Citation2020), as statistically projecting, rather than negotiating, the corporate budget was considered an improvement to its role in fulfilling budgeting purposes. Meanwhile, the Board paid increasing attention to forecasts in executive follow-ups to ensure that corporate targets were aligned with demands for reporting on alternative performance measures (Qu et al., Citation2015) and compliance with banking regulations (Nordberg & Stockenstrand, Citation2017; Stockenstrand, Citation2017).

A business controller detailed how forecasting ‘solves the task that the executives and Board of Directors get an overview, and it is not really the budget, it is more our forecasts … that they can see in which direction things are headed if we do these and these things’ (Interviewee 2). At the same time, another business controller explained how the budget served as an anchor point for cost control, as ‘we set a goal. We want to sail over there. Are we still doing that, or do we sail past, or what do we do?’ (Interviewee 3).

Consequently, the journey of budget abandonment and reintroduction caused a new understanding of the budgeting process. Considering the budgeting purposes altogether on the corporate profit level, the revenue-forecasts complemented the cost-budget by reinforcing the ability to simultaneously make forward-looking plans and ensure tight revenue and cost control during the fiscal year. Thus, using both control elements enhanced the overall effectiveness of overall budgeting. At the same time, when considering the planning and controlling of specific line items, the interrelationship was interchangeable, as forecasts could replace budgets for revenue items, and the budget replaced the forecasts for controllable costs (Bedford, Citation2020).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Following decades of budget criticism (e.g., Ekholm & Wallin, Citation2000), the Beyond Budgeting framework was presented as an alternative to traditional budgeting. This practitioner-oriented literature (Bogsnes, Citation2016; Hope & Fraser, Citation2003) argues that budgets should be abandoned and replaced by a new management control package (Becker et al., Citation2020). Svenska Handelsbanken has been presented as the prototypical Beyond Budgeting case (Lindsay & Libby, Citation2007), but other case studies of Beyond Budgeting have shown that budgets are often not entirely abandoned (Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Samudrage & Beddage, Citation2018; Valuckas, Citation2019). Libby and Lindsay (Citation2010) pointed out that many organizations adopt Beyond Budgeting principles without abandoning budgets, and the authors encouraged studying how companies combine traditional budgeting and Beyond Budgeting rather than resorting to an ‘either/or’ approach.

The tension between Hope and Fraser’s (Citation2003) proposal of completely replacing budgets and their seemingly prolonged or recurring use in practice motivated the study of how budget abandonment and subsequent reintroduction impact budgeting. Specifically, this study examined the use of budgets and forecasts in a bank that abandoned the corporate budget but later reintroduced it in a form where control elements were given new roles. In Shakespeare’s terms, the study showed how travelers may return to budgets, changed by their Beyond Budgeting inspired journey. We explored not only whether budgets were abandoned or not but also the reasons for budget abandonment and reintroduction when the budgeting process was developed in response to changing internal and external conditions. By considering budgets and forecasts as interdependent control elements in a budgetary control system (Bedford, Citation2020), we focused on how the formation of controllability and accountability affected their roles and interrelationships. Thus, the case study enabled us to investigate the temporal dynamics of management control systems (Martin, Citation2020) in a unique case company that had experienced both budget abandonment and reintroduction.

As in the study by Sandalgaard and Bukh (Citation2014), where budget abandonment was proposed as part of a business process reformation, the main reason for formally abandoning the budget in BankCorp was the restructuring of the data warehouse. Some of the control elements associated with Beyond Budgeting, such as internal benchmarking, were already present in the bank, so Beyond Budgeting was not introduced as an entire control package. Instead, Beyond Budgeting inspired the accounting department to fulfill budgeting purposes by developing a new forecasting model.

Having decided upon budgeting abandonment, BankCorp erased the term ‘budget’ from written policies and replaced the corporate budget with forecasts. Later, the budget was reintroduced, but the Beyond Budgeting inspired period broadened the understanding of budgeting. The Board of Directors experienced that forecasts could make executives outwardly accountable for realizing forecasted outcomes, and forecasts remained essential for revenue planning and control. Still, budgets were reintroduced to provide certainty and control costs. When separating reporting into groups of line items (i.e., revenue and cost), replacement occurred. Meanwhile, the forecasting model continued to play an important complementary role to the budget in the budget cycle when considering profit on an aggregate level.

This paper makes two overall contributions to the existing literature. First, by examining the developing interrelationships between budgets and forecasts across periods where significant changes were made to the budgeting system with inspiration from Beyond Budgeting, the study contributes to the empirical Beyond Budgeting literature (e.g., Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013; Valuckas, Citation2019). Previous studies have examined how control elements are configured as a package when Beyond Budgeting is implemented (O’Grady & Akroyd, Citation2016), but ‘we know relatively little about [Beyond Budgeting] implementation failures’ (Matějka et al., Citation2021, p. 183). This study enhances the understanding of budgeting and Beyond Budgeting by showing how and why organizations reintroduce budgets after abandonment.

Similar to other case studies of Beyond Budgeting (Bourmistrov & Kaarbøe, Citation2013; Henttu-Aho & Järvinen, Citation2013), this study demonstrated that BankCorp initially replaced budgets with forecasts, as the control elements, in the period of budget abandonment, were interchangeable. Also in correspondence with other studies (Becker, Citation2014; Valuckas, Citation2019), the study found that budgets were reinstated. BankCorp did not experience a replacing relationship with negative effects when budgets started co-existing with forecasts. Rather, the new forecasting model was perceived as a dynamic planning and control mechanism for revenue items, which started working in a reinforcing complementary relationship with the fixed cost-budget.

Contrary to previous case study findings (e.g., Henttu-Aho, Citation2018), the forecasts in BankCorp were not only used for accurate planning but also facilitated decision-making when attention was paid to discretionary actions rather than budget goal attainment. Since the corporate budget was reintroduced as a cost-budget, other control elements complemented the budget by reinforcing tight revenue and cost control. Besides the quarterly forecasts, the Board of Directors focused on the biannual external benchmark reports and analyses of actuals presented in monthly reports in their follow-ups. These control elements ensured continuous improvement and accounted for periodization and controllability issues.

BankCorp reintroduced the corporate budget when the data warehouse restructuring was finalized because budgetary information was commonly considered predominant in many reporting and control processes (Marginson & Ogden, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). Nevertheless, the forecasts remained, and this study shed light on which parts of the Beyond Budgeting package were deemed particularly useful in fulfilling budgeting purposes. Rather than considering budgeting reintroduction a ‘failed’ attempt to go Beyond Budgeting (Valuckas, Citation2019), the change processes in the bank led to a realization of the usefulness of both budgets and Beyond Budgeting inspired control elements. Becker et al. (Citation2020) depicted Beyond Budgeting as a radical departure from existing practice, and while complete budget abandonment may seem radical, this study showed that the properties of certain control elements (i.e., forecasting) should not be overlooked in organizations affected by macroeconomic uncertainty.

Previously, the limited research on budgeting reintroduction has shown that budgeting as an institutionalized control system may be difficult to dispose of, particularly in times of crisis (Becker, Citation2014), and indicated various intra-organizational reasons for maintaining budget-like control elements or returning to budgets (Valuckas, Citation2019). Besides recognizing the need for internal control as a reason for budget reintroduction, we attended to how external demands for accounting information cultivated a new understanding of the advantages of complementing cost-budgets with revenue-forecasts.

Bedford et al. (Citation2022) elucidated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tightened budget control but accentuated the need for future studies to investigate how external conditions impact control element interrelationships. This study clarified how an increased strategic emphasis on corporate targets (Huikku et al., Citation2021) and outward accountability (Stockenstrand, Citation2017), rather than the traditional emphasis on performance goals and upward accountability, impacted the relationship between forecasts and budgets in BankCorp. Not only are publicly traded companies required to disclose financial information as soon as forecasted results differ from expectations, but frequently updated forecasts are also useful for guiding financial analysts on alternative performance measures (Armstrong et al., Citation2016; Qu et al., Citation2015). As a result, external demands enhanced the role of the forecasting model in BankCorp's budgeting process. Instead of analyzing traditional budget variances, the Board of Directors compared forecasts to budgets to identify gaps between expectations and goals. Thereby, the forecasting model did not just generate passive projections but became part of future activities (Hansen & Van der Stede, Citation2004), as management commitment to forecasts gradually intensified throughout the fiscal year.

Ultimately, the study highlighted the importance of studying budgeting evolution (Martin, Citation2020), unfolding how abandonment and reestablishment processes impacted budgeting. Perhaps the case companies studied by Henttu-Aho and Järvinen (Citation2013) should not be defined as Beyond Budgeting companies, while BankCorp should not simply be considered as returning to traditional budgeting. In line with the proposals of Simons and Dávila (Citation2021), who established that the sequencing of events impacts the changes in the management control system, the study found that the roles of budgets and forecasts changed through the three temporal stages. Contrary to Toldbod and van der Kolk’s (Citation2022) findings, the effects were not cascaded to other control elements, such as external benchmarking or monthly reporting of actuals, which remained stable during the study period. However, the changes in budgets and forecasts were conditioned by the existing control systems, as shown by Bedford and Ditillo (Citation2022).

This study of budgeting dynamics also contributes to the management control systems literature (e.g., Bedford, Citation2020; Merchant & Otley, Citation2020; van der Kolk, Citation2019), which we have drawn upon as a method theory (Lukka & Vinnari, Citation2014). Previous quantitative studies have examined the interdependency between budgets and other control elements (Bedford et al., Citation2016; Kreutzer et al., Citation2016), following Grabner and Moers’ (Citation2013) systems approach. However, utilizing a dichotomous approach that clearly distinguishes between complementarity and replacement can be inadequate in detailing interrelationships, as control elements may be configured on a continuum from systems to packages (Demartini & Otley, Citation2020).

This is one of the first studies mobilizing Bedford’s (Citation2020) interdependency proposition to unravel various forms of complementarity and replacement. Forecasts may complement budgets by technically enabling the establishment of a reliable corporate budget and by managerially reinforcing profit planning and control. Still, forecasts may also replace budgets, as they are interchangeable for revenue and cost line items. While Huber et al. (Citation2013) thoroughly showed that the relationships between two control elements are not stable but form to become either replacing or complementary in given periods, this study illustrated how budgets and forecasts can simultaneously replace and complement each other after budgets are reintroduced depending on the operationalization of line items. Thereby, the study also provides an empirical example of van der Kolk’s (Citation2019) concept of ‘replacement,’ where control elements continue to co-exist despite their potential replacing relationship.

Moreover, the study enhances the literature by accentuating the importance of establishing which control problem the management control system aims to resolve. Control system effectiveness may be conceptualized as upward accountability (Bedford et al., Citation2016) or revenue generation (Kreutzer et al., Citation2016), but considering other control problems, such as ensuring outward accountability, may lead to other findings regarding control element interrelationships. Specifically, this study showed that, depending on whether the purpose of the budgeting system is to plan and control specific line items or overall profit, multiple forms of interdependency may co-exist within the same organization.