Abstract

Protectionism and anti-globalization tides have been rising already before the COVID-19 pandemic, with Brexit and the China-U.S. trade war, as two examples. A continued disruption to global trade, investment and value chains could worsen global development. Economic recovery will require restoring firms’ ability to trade, offshore and invest globally. To achieve this, it will be useful to understand the role of migration for foreign trade, investment and other aspects of internationalization. In this paper we review and discuss over 100 papers published about migrants’ roles on international trade, foreign direct investment and offshoring. Although the evidence suggests that migration facilitates trade and internationalization, we also note substantial gaps and inconsistencies in the existing literature. The aim of this paper is to encourage further research and assist policymakers in their efforts to promote economic recovery including internationalization.

1. Introduction

Protectionism and anti-globalization tides have been rising during the past few yeas, with Brexit and the China-U.S. trade war, as two examples. Certain policies implemented due to COVID-19 have further disrupted global trade, investment and value chains; difficulties in getting supplies of medical equipment have, for example, triggered an increased interest in de-globalizing value chains (Miroudot Citation2020). Many policies to combat the coronavirus pandemic have caused both short-term problems for fighting the pandemic, as well as risks in regard to economic recovery, employment, development and poverty reduction over the medium and long term (Evenett Citation2020; Hoekman, Fiorini, and Yildirim Citation2020; Zimmermann et al. Citation2020). Further, research indicates that uncertainty about the stability of the rules of the game has a significant negative influence on trade and investment, beyond the barriers imposed by the rules themselves (e.g. Handley and Limao Citation2013). Meanwhile, migration may have contributed to the recovery from the 2007 globala financial cirisis, for instance by reducing financial constraints (Cuadros, Martín-Montaner, and Paniagua Citation2016). To restore global trade, investment and value chains, which is important for economic development, it is crucial to understand the nexus between migration and internationalization.

International trade and flows of people and capital are viewed as substitutes in neoclassical economics. Recent research, however, suggests that there is a positive relationship between migration and trade, as well as other forms of internationalization, such as foreign direct investment and offshoring.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive yet accessible overview of the literature on the role of migration in international trade and investment. We review, summarize and discuss over 100 published papers on the subject, from pioneering country-level studies to nascent firm-level studies that utilize employer-employee data.Footnote1 To our knowledge, this is the first paper to provide a wide-ranging review of the different strands of theory related to the nexus between migration and internationalization, as well as early and new disaggregate empirical findings on migration and various forms of internationalization.

We organize the paper as follows: section 2 provides a background and introduces the conceptual framework; section 3 discusses theory; section 4 reviews the empirical evidence; section 5 concludes and discusses the policy implications.

2. Background

Because of the development of transportation technology, forward strides in trade liberalization, and the rise of global value chains, international trade stood at near record levels before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Global exports of goods and services more than tripled between 1990 and 2018, from $6.8 trillion in 1990 to $25.8 trillion in 2018, the last year of available data (World Bank Citation2020).

Migration has also increased substantially over the years, driven by a variety of factors, with social, political, cultural and economic circumstances all playing major roles (e.g. Massey Citation1993; Hatton and Williamson Citation2005; IMO Citation2019).

Despite technological progress and liberalization, internationalization still involves considerable costs. As ‘natural trade barriers,’ which consist of geographic factors, have become less significant – coupled with the reduction of conventional trade barriers, such as tariffs and quotas – the role of information, networks and trust in international trade has become relatively more important.

To engage in international business, firms need to acquire skills in international commerce and substantial specific information about their intended markets. Firms also need to be able to gain ‘deep’ access to remote markets, for example in the form of admission to distribution networks, and to establish trust with important market actors and customers. Subsequently, the issue of whether migration could be an instrument for facilitating internationalization has become more central.

Studies by Gould (Citation1994), Head and Ries (Citation1998) and others ignited research on the migration-trade nexus. The research has investigated migrants’ capacity to facilitate trade and other forms of international business activity. While most studies have focused on how migrants affect international trade flows at an aggregate level, recently some studies utilize matched employer-employee data instead.

The advancing role of migration in the context of internationalization has important and topical policy implications. Over the past few years the world had experienced a rise in numbers of both voluntary and involuntary migrants. Immigration – in the form of migrant workers and refugees – held the center stage in the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership, and the outcome was for the UK to leave the EU. The U.S. presidential election of 2016 also focused on the issue of immigration. The COVID-19 crisis has further increased the need for understanding the relation between migration and internationalization. As policies for recovery likely include restoring trade and other forms of internationalization, this balances pandemic risks with mobility.

Despite the extensive literature on this nexus and its important implications for policy, we have found very few examples of governments and policymakers highlighting the role of migration for firms’ trade and other aspects of internationalization. Apart from migration being a sensitive subject, one possible explanation could be the absence of an accessible and comprehensive survey of the available theory and evidence on the role of migration in internationalization.Footnote2

3. Theory

3.1. Traditional views of the migration-trade relationship

The traditional view in economics is that the cross-border movement of goods and factors of production are substitutes (e.g. Mundell Citation1957; Massey Citation1993). In a policy context, this has been translated into positions arguing for trade liberalization as a means of limiting immigration (Layard Citation1992; Aroca and Maloney Citation2005; Gaston and Nelson Citation2013).Footnote3 This logic was employed to support the North American Free Trade Agreement between the U.S., Canada and Mexico (Uchitelle Citation2007). Similarly, policymakers in the EU have hoped that liberalizing trade would alleviate migration pressures from new, and often poorer, member states (Geddes and Money Citation2011).

However, this basic neoclassical conclusion of substitutability between migration and trade does not hold up when some of the underlying assumptions of the model are relaxed, for instance, by allowing for non-identical technologies across countries. Then, even in a conventional factor proportions context, migration and trade can be complements (e.g. Markusen Citation1983; Schiff Citation2006).

A number of subsequent theoretical studies have demonstrated that various other settings can also determine whether migration and trade are substitutes or complements (e.g. Panagariya Citation1992; Kohli Citation2002; Hijzen and Wright Citation2010; Bowen and Wu Citation2013). The outcome may depend on the level of trade protection, migrant characteristics and the sectors where migrants are employed, and the elasticity of substitution between immigrants and intermediate inputs, among other factors. Rauch (Citation1991) expanded on this analysis in a Hecksher-Ohlin model, which incorporated patterns of both migration and trade, noting that migrants possess social capital that lowers trade costs and thus spurs trade.

Based on the traditional view of the relationship between migration and trade, we would expect substitutability to dominate.

3.2. An updated view of the role of migrants for trade

Recent trade theory postulates a complementary relationship between migration and trade. These models, pioneered by Clerides, Lach, and Tybout (Citation1998), Bernard et al. (Citation2003) and Melitz (Citation2003), focus on heterogeneous firms, imperfect competition, trade costs and intermediaries of trade.Footnote4

In the recent trade models, firms face fixed and/or variable trade costs, which only the most productive firms can afford. This, in turn, creates a threshold separating non-trading firms from trading firms, based on productivity. Consequently, a reduction in trade costs induces firm dynamics and reallocations, such as rising productivity within an industry.Footnote5 This effect, and access to imported goods varieties, generates positive welfare effects in general equilibrium in addition to more traditional sources of gain from trade.

In a nutshell, two mechanisms have been proposed for migrants’ impact on trade: one that is assumed to raise bilateral imports directly (the preference mechanism), and another that increases bilateral trade in general with the home country (the foreign market and contacts mechanism). While the first mechanism is straightforward inasmuch as it boosts demand for imported goods from immigrants’ source countries, the second mechanism includes three ways through which immigrants can lower transaction costs by disseminating their specific human capital in the host country: (1) by improving communication between the host and home countries, by means including increasing the number of bilingual people in the host country; (2) by contributing knowledge of products, preferences etcetera in foreign markets, i.e. the immigrants’ country of birth; and (3) reducing the costs associated with drafting and enforcing contracts, by infusing trust in trade relations by providing access to immigrants’ contacts.

Primarily, migration has been assumed to influence trade with those immigrant source countries that lack formalized procedures for contracting, which usually means developing countries.Footnote6

According to Gould (Citation1994), the less information available in the host country before immigration, the greater the trade impact of immigration. This is modeled by assuming that transaction costs are concave in the immigrant stock. Additionally, there is an assumed positive relationship between the migrant impact on trade and immigrants’ ability to transmit information as they integrate more successfully into their new country. Accordingly, the factors that may affect this relationship are the existing stock of immigrants in the host country from the home country and the integration of immigrants.Footnote7

3.3. Towards a modern view

Early studies on the trade-facilitating role of migration lacked a clear idea of the meaning of proximity between immigrants and business in host countries. Moreover, early studies neither considered the historic importance of networks and trust, nor business literature on the role of psychic distance and uncertainty in internationalization.

Rauch (Citation1996, Citation1999) provided a network and search perspective of trade in differentiated products. Although migrants were not explicitly included in Rauch’s theoretical framework, it was influential to subsequent literature for emphasizing that networks can reduce search costs and improve matching in foreign trade.

This new framework was consistent with the concept of economies of scope in search activities, which, for example, rationalize trading intermediaries.Footnote8 The potential to ‘free ride’ on other parties’ searches may motivate public trade promotion activities. Finally, the network perspective would appear to give personal relations a more prominent role in trade, through ethnic, cultural social ties. Rauch (Citation2001) argued that the repeated game nature of a network fosters trade, but may become less important over time as institutions develop.

Chaney (Citation2014) developed a dynamic network model of trade, which relates unexplained heterogeneity in trade behavior to firms’ foreign networks. In this model, firms need at least one contact in a foreign country to export there. Firms may search for contacts randomly or use existing networks. Once acquired, contacts abroad may allow the firm to remotely access contacts’ networks in neighboring countries. Consequently, firms with many contacts have an advantage in foreign trade.

Networks may divert trade from ‘good’ agents in favor of links with the ‘wrong’ agents (Casella and Rauch Citation1998; Rauch and Casella Citation2003; Lewer and Van den Berg Citation2009). Consequently, this may damage other agents, the host and home countries, as well as third countries. For example, an immigrant network may create trade with, or divert trade to, foreign countries with relative factor endowments that are more like the host country than some other foreign country, to the detriment of the host country, and possibly the world. A similar mismatch may occur at the firm level to the detriment of the firms that are excluded from immigrant networks, with potential negative effects on allocative efficiency in the host country.Footnote9

It should be recognized that cross-border movement of people also take place within firms. Migration is in part the result of multinational enterprises’ production sharing decision in regard to their global value chains. The influence of within-firm flows of migration on trade is scantly explored theoretically. Recently, however, empirical research has begun to study the potential role of temporary employee migration on trade. Furthermore, it is possible that expat workers can influence trade through the cross-border transfer of technology as discussed by Inzelt (Citation2008), Markusen and Trofimenko (Citation2009), and Golob Šušteršič and Zajc Kejžar (Citation2020), where local workers’ training could be of importance (Markusen and Trofimenko Citation2009). The possibility that technology could be an indirect channel through which migration may spur trade and promote internationalization is supported by the seminal study by Foley and Kerr (Citation2013) and further backed up by studies such as Bahar and Rapoport (Citation2018).

3.4. Migrants and heterogeneous firms

Theoretical contributions have more recently emerged considering migrants within heterogeneous firm models of trade. In this vein, Tai (Citation2009) incorporated the impact of immigrants on trade a firm model of trade with monopolistic competition, multiple sectors and fixed and variable costs of trade. The additional parameter included in this model was bilateral preferences between countries.

Conceptually, Tai (Citation2009) expects immigrants’ bias in demand for home country products – what White (Citation2007) called the transplanted home bias – to be transmitted to others in the host country, so as to further increase aggregate imports (the preference effect). The fact that Tai (Citation2009) envisions transmission to the surrounding community paves the way to considering a wider trade impact of preferences, since immigrant communities generally constitute a small share of the population. Moreover, it is implicitly assumed that preferences may be transmitted from the host to home countries.Footnote10 Besides cultural transmission of preferences, immigrants are also assumed to reduce fixed trade costs related to information and opportunism (the network effect).Footnote11

Importantly, the market structure of industries can influence these mechanisms, as characterized by the constant elasticity of substitution in demand of an industry. Bastos and Silva (Citation2012) introduced migration into a heterogeneous firm trade model, but with a slightly different focus: how emigration could contribute to idiosyncratic firm-specific shocks in export demand. In the model, firms from a particular country are provided with better access to networks in a foreign country through the presence of emigrants (from the firm’s home country) in that country.

Emigrants are assumed to facilitate market entry for firms from their source country. In this setting, networks increase the likelihood of starting to export and the revenues from export. Moreover, networks in a foreign country provided through emigration are assumed to lower the economy-wide fixed cost of exporting, which raises export propensity for all firms to the foreign country.

Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2016) modified a model to analyze the role of immigrant employees for firm trade, while controlling for transplanted home bias of immigrant stocks in the host country.Footnote12 In this model, immigrants’ export-promoting capability is derived from three mechanisms: (1) immigrants’ reduction of the costs of export entry;Footnote13 (2) immigrants’ transplanted home bias that makes firms in the host country more familiar with the foreign market, which in turn promotes exports, and (3) firms in the host country introducing modified or new products to cater for immigrant demand, which are subsequently exported to immigrants’ home countries.Footnote14 The framework allows for immigrant employees to reduce uncertainty in entry into and continued presence in foreign trade for the firm. By improving information and reducing asymmetries in information, immigrant employees are expected to reduce not only fixed, but also variable, trade costs to increase the propensity and intensity of exports.Footnote15

While the theoretical literature on migration and trade rarely distinguishes between trade in goods and services, Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2019) focus on the role of foreign networks – through immigration – for firm services exports.Footnote16 The paper assumes that this is realized through better access to information and contacts that reduce uncertainty in exports. The greater the informational frictions in a sector, the larger the investment a firm will make. However, the downside with the firm’s investment in foreign networks is that other firms in the vicinity may ‘free ride’ to gain improved, though not fully commensurate, access to the foreign market. This feature discourages investment.Footnote17 Conditional on certain parameter values, what emerges mimics typical social networks, which are clustered, and yet agents are only a few referrals away from other clusters.

3.5. The different dimensions of the migration-trade nexus

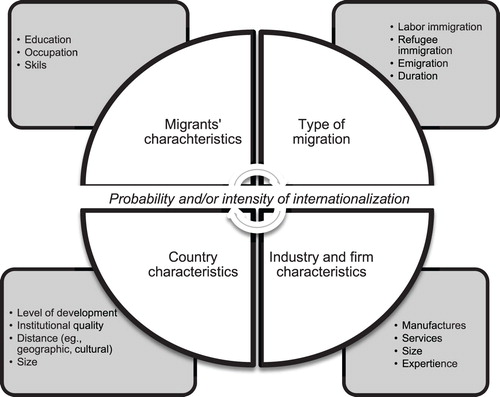

There are different theoretical hypotheses on factors that affect the degree to which migrants may influence internationalization, summarized in Figure .

Many studies view immigrants as a homogenous group with no variation in their capability to facilitate trade. Some studies, however, presume that some migrants are more able than others in this respect. This ability is often related to educational attainment (e.g. Gould Citation1994). More recent studies have considered migrant occupations. For example, Aleksynska and Peri (Citation2014) argued that occupation is a suitable proxy for the trade-promoting potential of migrants, whereas education credentials may not transfer readily across borders and migrants may not be matched to work commensurate with their education. They expected migrants in the top tier of occupations, such as managers, to have the greatest effect on trade, those in sales-related occupations to have an intermediate effect, and others to have the least effect. Similar expectations were incorporated in studies by Mundra (Citation2012) and Blanes (Citation2010).

Other migrant characteristics that are expected to influence the impact on trade are, e.g. entrepreneurship (Ivanov Citation2008; Faustino and Peixoto Citation2013), and age, because age is assumed to be related to more information about the home country (Koenig Citation2009). As regards entrepreneurship, migrants may be well suited through knowledge about foreign technologies and innovations. On the other hand, discrimination, difficulties in the transfer of skills, and minimum wages may push migrants into self-employment. Moreover, Ivanov (Citation2008) finds that many self-employed immigrants are in non-tradable sectors.

Integration into the labor market could also influence the extent to which migration may influence trade. Few studies have explicitly explored this aspect. Nevertheless, Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2015) argued that migrant groups that are more integrated into the labor market – such as males and non-refugees – are likely to have a greater impact on trade.Footnote18

In addition to migrant characteristics themselves, it is possible that firms that become more diverse through the hiring of migrants change the dynamics of workforce in ways that would benefit internationalization beyond knowledge and contacts. Parrotta, Pozzoli, and Sala (Citation2016) noted that diverse companies are like a ‘cosmopolitan world in small scale,’ in which all employees learn to interact with other cultures, which could improve firms’ ability to trade internationally.

Most studies assume that immigrants mainly affect trade between their host countries and their countries of origin (e.g. Chinese immigrants to the U.S. and their influence on trade with China), whereas only a few studies have explored the corresponding possible effect of emigrants on trade (i.e. American immigrants in China and their influence on U.S. trade with China), such as Tadesse and White (Citation2011). And few studies have investigated the role of particular ethnic networks, or even the role of domestic migration (Rauch and Trindade Citation2002; Combes, Lafourcade, and Mayer Citation2005; Felbermayr, Jung, and Toubal Citation2010; Artal-Tur, Ghoneim, and Peridy Citation2015). As discussed by Felbermayr, Grossmann, and Kohler (Citation2015), a diaspora may not only benefit trade between the host and home country – a direct link – but may also facilitate trade between host countries of the diaspora, i.e. an indirect link.Footnote19

More attention has been paid to characteristics of countries, either the foreign country where immigrants come from, or where emigrants reside.Footnote20 In general, migrants are expected to promote trade more with less developed countries, where institutions are weaker (e.g. Vézina Citation2012). By the same token, migrants are presumed to enhance trade more with culturally distant countries (e.g. White Citation2007).Footnote21

Several studies have hypothesized that migrants are particularly important for firms’ trade in differentiated and complex products (e.g. Rauch and Trindade Citation2002; Peri and Requena-Silvente Citation2010).Footnote22 A few studies have also assumed that trade in intermediate products is more assisted by migrants (e.g. Ivanov Citation2008; Faustino and Peixoto Citation2013). The study by Hatzigeorgiou et al. (Citation2017), which draws on the papers of Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg (Citation2008, Citation2012) relates to this. The authors argued that information frictions and principal-agent problems are aggravated in offshoring of production, so migrants are expected to be particularly instrumental in facilitating such imports.Footnote23

A final dimension of the migration-trade relationship is the margins of trade: do migrants primarily contribute to trade with a new country, with new products, or mainly through intensified trade with existing trade partners, as well as already traded products?

Most studies analyze the relation between bilateral migration stocks and trade volumes, which is akin to the intensive country margin of trade if only established trade is considered. However, some studies emphasize that migrants also facilitate trade with new foreign trade partners, e.g. White and Tadesse (Citation2008); Koenig (Citation2009); Bastos and Silva (Citation2012).

Moreover, one common assumption is that migrants reduce the fixed cost of trade so new trade is stimulated. Most recently, this has been taken to the product level. Migrants are expected to reduce the fixed costs of starting to trade in a new product internationally, and the variable costs of trading it. The former is expected to create new trade, while the expectations on the latter’s impact on trade are more ambiguous (Hiller Citation2013; Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk Citation2019).Footnote24

3.6. Migration and foreign investment

The literature on migration and foreign direct investment (FDI) is less developed than that on migration and trade, although the research is expanding.Footnote25 As with with trade in goods, a neoclassical analysis would conclude that other factor flows are substitutes. However, if instead, firms want to supply the foreign market, to avoid import tariffs for example, and therefore make (horizontal) investment, that investment may need to be accompanied by personnel. This would imply that migration and investment are complements. It can be noted that this assumption permeates trade and investment agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which provides for easy visas for FDI personnel.

Considering that FDI is associated with even larger fixed costs, risks and uncertainty than trade – firms need to establish themselves physically abroad, hire personnel, deal with foreign suppliers and authorities – migration may be instrumental to vertical FDI. This is along the lines of, inter alia, Rauch (Citation2001). Moreover, such barriers are likely to sustain the positive relationship between migration and FDI as regards horizontal investment. Therefore, studies on migration and FDI have typically hypothesized that the relationship is a positive one, irrespective of the motive of the investment (e.g. Gao Citation2003; Lewer and Van den Berg Citation2009). Most commonly, the underlying notion has been that immigrants promote investment in their country of origin through their foreign knowledge and contacts, reducing information frictions (e.g. Bhattacharya and Groznik Citation2008; Javorcik et al. Citation2011; Buchardi, Chaney, and Hassan Citation2019).

Federici and Giannetti (Citation2010) incorporated the positive external effects of migrants on FDI. In their dynamic two-country model, emigrants reveal information about their country of origin to investors of the host country. Information is conjectured to lower the risk and costs of investment. In addition to the return on capital abroad and labor efficiency, information becomes a determinant of capital flows to the foreign country. Capital moves freely across borders, while migration does not.Footnote26

More recently, Cuadros, Martín-Montaner, and Paniagua (Citation2019) have provided a heterogeneous firms model of FDI where high-skilled migrants potentially play a key role. Migrants in managerial or profesional occupations help affiliate firms in relations with headquarters. They assist in communication with headquarters and in translating headquarter blueprints for use in the foreign affiliate. In this model, an increase in the relative share of high-skilled (low-skilled) migrants promotes (reduces) FDI both at the extensive and intensive margins.

Concerning heterogeneity in the impact of migrants on FDI, the literature has hypothesized that migrants are particularly instrumental in relation to investment in more distant countries in terms of language, culture and institutions, and in regard to countries with weak institutions (e.g. Johanson and Vahlne Citation1977, Citation2009; Gao Citation2003; Murat and Pistoresi Citation2009; Lücke and Stöhr Citation2018). As already touched upon, another assumption is that it is mainly skilled migrants that facilitate FDI (e.g. Flisi and Murat Citation2011; Cuadros, Martín-Montaner, and Paniagua Citation2019). However, as Kugler and Rapoport (Citation2007) noted, other migrants may at least provide firms with information about the quality of labor abroad, so that uncertainty is reduced and FDI promoted. In a similar vein, Flisi and Murat (Citation2011) expected that migrants’ time in the host country to correlate positively with influence in economic decision-making. Murat and Pistoresi (Citation2009) argued that migrant networks may be particularly useful for small firms’ FDI.

4. Evidence

4.1. Macro-level evidence

To date, a total of approximately 70 macro-level studies on the migration-trade nexus have been conducted. Around 15 individual countries and their trade relationships with basically all their trading partners have been studied.

Table summarizes the main estimates of the macro-level studies to provide a stylized overview of the evidence.Footnote27 The elasticity of trade with respect to immigration (measured as the stock of migrants in the host country) is in the span 0.21–0.22. That is, a one percent increase in a country’s foreign-born population is associated with a 0.2 percent increase in trade with immigrant source countries, on average and all other things being equal. The median elasticity is lower, however, which implies that some studies have disproportionately impacted the overall picture. The size of the general macro-level relationship is closer to an elasticity span of 0.15–0.20.Footnote28

Table 1. The macro-level evidence – elasticities across studies.

Fewer than twenty studies have investigated the role of emigration and trade. These studies indicate a weaker relationship relative to immigration. The median elasticity is approximately 0.1, which suggests that a one percent increase in the stock of one country’s emigrants in a certain other country is associated with 0.1 percent more trade between the two. Although this result is based on few studies and should be interpreted cautiously, it is arguably substantial in economic terms.

Imperfect information affects trade differently, depending on products. For example, trade in electronics tends to be sensitive to information in terms of quality, brand and origin. Imperfect information for such relatively advanced products hampers trade more than for basic products.

Since the trade-facilitating influence of migration is postulated as derived, in part, from the ability of migrants to reduce information friction, empirical studies have analyzed how migration relates to trade in products with varying degrees of sensitivity towards information friction.

Our review of the macro-level evidence suggests that migration is more strongly related to immigrant host countries’ imports relative to exports, especially if we put less emphasis on results that deviate substantially from the bulk of the empirical studies. The elasticity of trade with respect to immigration is approximately 0.18 for imports and 0.15 for exports. The discrepancy between the immigrant correlation vis-à-vis imports on the one hand, and exports on the other, is interpreted by most studies as an suggestive of the theoretical postulation that both the preference mechanism, and the foreign market and contact mechanism, play a role in explaining the migration-trade nexus.

The relatively high impact of those born abroad on trade in differentiated products, compared with homogenous products, suggests that the migration-trade link depends on migrants’ ability to improve the information flow between countries and increase confidence in business transactions (Casella and Rauch Citation2002).

The macro-level results also vary with characteristics of migrants and countries. Some variations are expected from theory, e.g. a stronger relationship in terms of skilled migrants and for less developed countries. In addition to characteristics related to migrants’ skills and educational attainment, Martín-Montaner, Requena, and Serrano (Citation2014) and Cuadros, Martín-Montaner, and Paniagua (Citation2019) investigated the role of the tasks or occupations carried out by migrants. Their results indicated that higher prevalence of managerial duties or occupations among migrants enhances the trade and FDI promoting effect of migration.

Potentially, reverse causality between migration and trade is a severe problem for the macro-level studies. If trade spurs migration rather than vice versa, the treatment variable is to be considered endogenous. Several studies have attempted to analyze the direction of causation, generally using instrumental variable analysis.

Gould (Citation1994) conducted an econometric causality test and found that immigration precedes trade for most of U.S. trading partners. Furthermore, Gould emphasized how immigration flows are restricted by binding quotas, which should make migration exogenous with respect to bilateral trade flows.

McKenzie (Citation2007) analyzed passport and legal barriers to emigration in a large sample of countries and concluded that countries with high passport costs have lower levels of emigration. Therefore, passport costs may impede migration. Javorcik et al. (Citation2011) utilized this finding when assessing the relationship between migration and FDI in the U.S.. Although Gould (Citation1994), Dunlevy and Hutchinson (Citation1999), Javorcik et al. (Citation2011), Aguiar, Walmsley, and Abrevaya (Citation2007), McKenzie (Citation2007), Sangita (Citation2013) and others concluded that the positive relationship between migration and trade ought to be viewed in terms of a causal influence, the macro-level studies cannot be said to have conclusively demonstrated that the direction of causality runs from migration to trade.

4.2. Sub-national evidence

There are approximately 25 studies that have analyzed the role of migration for trade at the at the sub-national level. That is, studies that have exploited regional data to explore the role of migrant stocks across regions within countries for those countries’ trade with migrant source countries. These studies have utilized regional data from U.S. and Canadian states as well as regions within European countries, and in one case, for Mexican states.

The sub-national-level studies are more homogeneous than their macro-level counterparts inasmuch as they focus on immigration and exports almost exclusively.

The macro-level evidence on the migration-trade link for Canada was confirmed by Partridge and Furtan (Citation2008), which studied immigrants’ contribution to Canada’s foreign trade on the provincial level. Furthermore, Peri and Requena-Silvente (Citation2010) analyzed how immigration to 50 Spanish provinces affects exports to 70 different countries in the period 1995–2008. They found a positive and significant relationship between immigration to Spanish provinces and their exports to immigrant source countries.

Several sub-national-level studies have applied methods, such as instrumental variable analysis, to test the causal direction of the relationship.Footnote29 In general, the sub-national-level evidence confirms the positive trade-facilitating potential of migration. As demonstrated in Table , the median estimated coefficient provided by these studies is 0.14 for exports and 0.23 for imports. The variation across studies that estimate a positive migrant influence on regional foreign trade has diminished over time. We attribute this to more recent studies employing more reliable data and methods. Finally, we note that more robust sub-national evidence has started to emerge on the complementarity between migration and FDI (e.g. Buchardi, Chaney, and Hassan Citation2019; Mayda et al. Citation2019).Footnote30

Table 2. The sub-national-level evidence – elasticities across studies.

4.3. Micro-level evidence

Firm-level studies of the migration–trade nexus have started to emerge recently. This development in research is important for being able to investigate the multifaceted role of migration on internationalization as postulated by the theory.

Migrants neither obtain information on all host country opportunities without effort, nor do they diffuse relevant foreign market information uniformly to all host country firms. Far from all migrants possess the relevant information and contacts enabling them to act as host-country agents for trade. Ultimately, the specific firms that benefit from international contacts and superior information about foreign markets can utilize this human and social capital to identify and exploit foreign trade opportunities. For example, Herander and Saavedra (Citation2005) emphasized how the proximity between migrants themselves – and between migrants and firms – play an important role in the exchange of trade-related information, which implies that primarily, migrants are expected to have a local trade-facilitating effect.

The first group of empirical firm-level studies typically combined country or regional migrant stocks with firm trade data to analyze possible firm-level migration–trade links. These were generally executed within a gravity model framework. Overall, the expected key role of proximity on migrants’ impact on foreign trade was borne out in these studies.

Koenig (Citation2009) examined the relationship between a measure of regional immigrant stocks in 1982 and the export propensity of French firms vis-à-vis 61 countries between 1986 and 1992. The results demonstrated a positive and statistically significant association between regional immigrant stocks and firm export propensity, especially for immigrant groups with a higher average age and level of education. On average, a one percent increase in the immigrant stock was associated with a 0.12 percent increase in the likelihood of firms to exporting to immigrant source countries.

Based on an analysis of firm exports from a set of European countries and the regional share of immigrants in four central European countries, Pennerstorfer (Citation2016) concluded that the proportion of immigrants is strongly related to export propensity. Further, a one percent increase of the number of immigrants in a region is associated with 0.08 percent higher firm exports to immigrant source countries.

Andrews, Schank, and Upward (Citation2017) examined whether employees with foreign citizenship could explain why some firms decide to export and the share of exports in total sales, using a sample of German exporters in the 1993–2008 period. They identified a significant effect on firm-level exports from the nationality of workers. A one standard deviation increase in the proportion of foreign-citizenship workers in a firm increased the probability of export by 1.5 percent. The effect was substantially stronger for migrants in senior occupations.

Hiller (Citation2014) studied the relationship between total emigrant stocks (the number of Danish citizens living abroad) and exports for a cross section of firms in Denmark in 2001, very similar to Bastos and Silva (Citation2012) for Portugal in 2005. The former study indicated that emigrants only foster exports of small firms, while the latter suggested that firms in regions with historically large emigration flows are more likely to export, and that they export more.

The second group of firm-level studies all exploited detailed trade data at the firm-level coupled with data on immigrants employed in the firms. The most detailed studies to date are Hiller (Citation2013), Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2016), Marchal and Nedoncelle (Citation2017), as well as Cardoso and Ramanarayanan (Citation2019).

Hiller (Citation2013) analyzed Danish manufacturing exporters in the period 1995–2005. This study found a positive – yet quite statistically weak – association between immigrant workers and firm export sales. On average, an additional immigrant employee increased firms’ exports to immigrant source countries by an estimated one percent. This positive influence of immigrant employees on firm exports was corroborated by Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2016), who studied all Swedish manufacturing firms with more than ten employees in the period 1998–2007. The estimated influence of hiring an additional immigrant was similar in scale to Hiller (Citation2013), increasing firm exports to immigrant source countries by approximately one percent on average.

Cardoso and Ramanarayanan (Citation2019) studied Canadian incorporated manufacturing exporters in the period 2010–2013 and also found a positive association with export sales but also with export propensity, yet with strongly diminishing returns to hiring immigrants. Unlike the other three studies, Marchal and Nedoncelle (Citation2017) lacked bilateral information on immigrant employees’ origin and instead used the foreign-born status of employees in studying French manufacturing exporters in the period 1997–2008. The authors found that, on average, a firm hiring foreign-born employees exported 30 percent more than a control firm that was as likely to hire a foreign-born but did not.

Finally, a few attempts have been made to explore other firm-level aspects of the relationship between migration and internationalization than trade in goods. Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk (Citation2019) studied the relationship between immigrant employees and firms’ exports of services. They developed a heterogeneous firm framework and drew on employer-employee data for Swedish firms in the period 1998–2007. The results suggested that immigrant employees facilitate services exports; hiring one additional foreign-born worker can increase services exports by approximately 2.5 percent on average, with a stronger effect for skilled and recent immigrants. In addition to testing the validity of the trade-facilitating role of migration for services, this analysis aided understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the role of migration in internationalization. Provision of services often requires a considerable degree of mutual trust between sellers and buyers, which creates a need for firms to establish links with foreign markets to reduce information friction and promote trust.

Concerning migration within multinational enterprises, but across borders, and the possible effects on trade, the studies of temporary migration is of interest. For example, Lodefalk (Citation2016) exploited data on migration and country of birth to study temporary expats in Swedish firms and exports of merchandise and services as well as underlying mechanisms. Temporary expats were found to be positively associated with exports and their link with export intensity to be larger for services than for manufactured goods. Further findings also suggested that temporary expats are encouraging exports by assisting firms to overcome informal destination-specific barriers.

In addition to services, offshoring is an important aspect of firms’ internationalization. However, offshoring comes at a cost, especially where information or trust is lacking. Immigrant employees could reduce such offshoring costs through their knowledge of their former home countries and via access to foreign networks. Hatzigeorgiou et al. (Citation2017) studied Swedish firms and found that that immigrant employees spur offshoring activities by firms through lower offshoring costs.Footnote31 Hiring one additional foreign-born worker can increase offshoring up to three percent on average, with stronger effects for skilled migrants.

A final comment on the micro-level evidence is that endogeneity in this context may be due to reverse causality caused by the influence of preexisting commercial relationships or foreign demand shocks in firms’ decisions on immigrant hiring. This leads to the important question as to whether firms deliberately hire foreign-born workers to increase internationalizing activities toward immigrant source countries, or whether hiring decisions are exogenous with respect to internationalization activities. If the latter is true, this would imply that immigrants promote internationalization. But if, on the other hand, firms hire immigrants from countries that they already have established commercial relationships with, and/or hire immigrants as a way of increasing internationalization prior to implementing their internationalization plans – a sort of preparatory behavior emphasized in recent trade models (e.g. Lopéz Citation2009) – this would imply that immigrant employment is endogenous to the trade decision.

Overall, the emerging firm-level evidence tends to support the hypothesized key role of proximity for migrants’ impact on trade. However, much remains to be explored with respect to how – through which channels and mechanisms – migrants might facilitate firm internationalization, not least because the evidence on trade impacts across firms, firms’ products and product margins, as well as across groups of migrants with different human and social capital, is scarce. Additionally, modelling of migrant hiring decisions needs more attention to further consider endogeneity issues.

5. Conclusions

Our review of the literature on the nexus between migration and internationalization demonstrates that, in general, migration has the potential to promote trade and internationalization. Therefore, policymakers may draw on this knowledge to increase the chances of a successful economic recovery from the rising protectionism and trade wars of the past years, and from the exabberated economic effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression (Gopinath Citation2020).

Migration has been shown to be an inherently sensitive subject and a relevant factor in the policy debate over globalization.Footnote32 Therefore, as governments begin to draw up their post-pandemic economic plans, it is possible that policies regarding cross-border mobility of people will not be reset to normal. Considering the findings of this literature review, this could mean a worse deal for firms’ trade opportunities going forward.

Notwithstanding the theory and the evidence, there are still important gaps in the research. Concerning theory, there is no formal framework tying together migration with its wider role in internationalization. Specifically, the nexus between migration, trade and FDI is insufficiently explained by theory, despite the reasonable assumption that clear linkages do exist (e.g. Fontagné Citation1999).

The nascent firm-level approach has the potential to bridge several of the existing knowledge gaps, however the research is still in its initial stages.

Studies suggest that migrants’ educational attainment and company position matter for the capacity of migration to act as a facilitator of internationalization. The fact that skills seem to enhance the enabling role of migrants in internationalization can be viewed as support for the theoretical proposition that migrants provide knowledge and contacts that reduce information friction in international business. Yet there still is little firm-level evidence on the possible role of company position for the role of foreign-born employees in facilitating trade and foreign direct investment.

Based on the empirical evidence, there is reason to assume refugees matter less as facilitators for internationalization, at least in the short term (e.g. Head and Ries Citation1998; White and Tadesse Citation2010), and the reasons may seem obvious. It is inherently true that refugees’ hail from countries suffering in conflict, with very unfavorable conditions for international commerce and foreign investments.

There needs to be more research on the causal characteristics of the relationship in order to determine, beyond doubt, whether and how migration does, in fact, promote foreign trade. We conclude that macro-level data cannot be used to rule out the endogeneity concern completely. Exploiting granular data with state-of-the-art methods, such as quasi-experimental estimation techniques, is likely to be a promising avenue. In addition, more research on long-term effects is needed, as well as studies of indirect channels of influence via, inter alia, productivity (in the spirit of, e.g. Mitaritonna, Orefice, and Peri Citation2017).

Due to the still existing gaps and inconsistencies in the research, we suggest that policymakers align decisions with findings that are robust and consistent across many studies. For example, the evidence is relatively strong when it comes to education, which seems to be an important factor for the ability of migrants to help firms in their global trade activities.

In sum, based on the extensive research available, a successful strategy for economic recovery and poverty reduction in the years to come entails restoring cross-country mobility of trade in goods, services and investment as well as promoting better opportunites for people with the necessary skill sets to move across borders to facilitate firms’ internationalization.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for valuable comments and suggestions by Alan Deardorff, Gary Hufbauer, the editor of The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, two referees, and from participants at the annual conference of the Swedish Network for European Studies in Economics and Business. We also tank Frida Nilsson for very capable research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 To obtain a comprehensive overview of previous literature, we created a database. The database was populated by collating information on the existing studies in an integrated spreadsheet, which categorized studies by year of publication, level of analysis, estimation method and results.

2 For previous overviews, see Felbermayr, Grossmann, and Kohler (Citation2015) and Gaston and Nelson (Citation2013), and for meta-analyses, see Genc et al. (Citation2011), Lin (Citation2011) and Nijkamp, Gheasi, and Rietveld (Citation2011). Nathan (Citation2014) provide a survey of the wider economic impats of migrants, with an emphasis on skilled migrants.

3 For a discussion, see, e.g. Carbaugh (Citation2007) and for an empirical analysis, see, e.g. Río and Thorwarth (Citation2009).

4 The role of trusted intermediaries, such as migrants, has also been evident historically (e.g. Greif Citation1993).

5 Bernard, Redding, and Schott (Citation2007) present a model that also features trade gains from reallocations between sectors.

6 Blanes (Citation2010) argued that an impact of immigrants on trade with countries that have different institutions but not on trade with others would indicate an absence of an ethnic network effect of immigrants through contacts. However, the ethnic network or trust effect would be likely to operate also in trade between similar and institutionally weak countries. For trade between similar and institutionally strong countries, personal relations are also likely to lubricate international commerce, but not as much.

7 The additional trade impact of well-educated immigrants may not materialize if their skills are downgraded, because of poor labor market integration (Aleksynska and Peri Citation2014).

8 Rauch and Watson (Citation2004) develop a model where persons with foreign networks may either exploit them themselves or offer their services to others. Problems related to contracting and externalities, as well as the cost of maintaining networks abroad, affect the choice between individual exploitation or provision to others.

9 Research on distributional impacts within and between industries of foreign networks is largely absent but would seem worthwhile. Another caveat is that migration may spur new production at home or in the host country that replaces existing trade (Mundra Citation2005; Dunlevy and Hutchinson Citation1999; Hiller Citation2014).

10 Such transmission is akin to the absorption of preferences that Good (Citation2013) discusses, where he also argues that migrants need to keep their links to networks at home alive for absorption to take place.

11 White and Tadesse (Citation2008) envision that migrants can create and intensify trade by reducing opportunism through the creation of bridges across cultural distances—in terms of norms and values—between countries. Meanwhile, Rauch (Citation2001) explains the mechanism by referring to the moral bonds of and risk of exclusion from a network. Arguably, this explanation hinges on the network being sustained through new migrants or continued interaction. Accordingly, in overall terms, it is possible that migrants reduce both fixed and variable trade costs related to opportunism.

12 Other recent heterogeneous firm frameworks with immigrants affecting trade costs and productivity are, e.g. provided in Marchal and Nedoncelle (Citation2017) and Cardoso and Ramanarayanan (Citation2019). The productivity effect may, e.g. stem from task specialization of natives or immigrants being exceptionally talented or skilled (e.g. Peri and Sparber Citation2009; Peri, Shih, and Sparber Citation2015).

13 Koenig (Citation2009) models immigrants’ impact as increasing the probability to export through their negative effect on fixed export costs.

14 These indirect impacts of immigrants are somewhat akin to what Good (Citation2013) coins the revealed preferences effect of immigrants, whereby migrants indirectly—through their market transactions—disclose information to agents in their host country about preferences in demand of the home country and thus can promote exports to their home country indirectly.

15 There are several reasons why variable costs can be lowered through migrants’ assistance. Absence of opportunistic behavior and presence of trustful relations do arguably need continuous attendance through the maintenance of networks, perhaps even by the continuous entrance of new migrants, as discussed by Gaston and Nelson (Citation2013). Such maintenance is likely to require face-to-face contacts, although modern means of communication may be a complement (Hatzigeorgiou and Lodefalk Citation2019). As for the information channel, a continuous flow through migrants and their networks may be important for tracking changes in foreign demand and supply, especially for trade in advanced or fashionable items, as well as in regulations.

16 The only other studies we are aware of on the nexus between migration and general trade in services are the unpublished manuscripts of Foster-McGregor and Pindyuk (Citation2013) and Bowen and Wu (Citation2013), the latter of which does not feature the effect of migration on trade costs. In addition, there are a few studies on migration and tourism services, such as, domestically for Spain and externally for New Zealand (Law, Genç, and Bryant Citation2013).

17 In the model, investment by other firms is expected to reduce a firm’s own investment, and therefore indirectly its own services exports, while others’ investment directly promotes the firm’s exports.

18 Besides labor market integration, other aspects are particular for refugees. On the one hand, refugees may facilitate trade less than non-refugees because of their strained relation to the country from which they have fled, weakening their special and up-to-date information. They may also limit interactions with the home country, e.g. to avoid negative consequences for themselves or their connections (Head and Ries Citation1998). Having spent considerable time in diaspora before entering the host country, would also weakening their ties to home countries (White and Tadesse Citation2010). On the other hand, there is likely a non-randomness into refugee emigration. Some refugees may be particularly able persons who had been politically influential at home and who have managed to flee. This self-selection and the resulting cohort quality as well as factors of both the sending and receiving country may affect the contribution of the refugees to the host country (Borjas Citation1987), including positive effects on trade and FDI. Refugees may also be more eager to return than other immigrants, thereby strengthening their ties to the home country.

19 Felbermayr, Jung, and Toubal (Citation2010) argue that this indirect impact is a better measure of the trade-facilitating role of migrants than the direct impact, because the home-bias in trade is assumed to operate between the host and home country but not between host countries.

20 In more than 35 studies differential impacts across countries are studied. In at least four of them there is a prior of stronger impacts for countries at a lower level of development.

21 Other aspects of psychic or institutional distance supposed to augment the positive impact on trade include, e.g. having a different religion, no colonial relations in the past, and different languages. A study from the international business literature also discusses the contribution of ethnic homogeneity and strong family ties in home countries to the migrant-trade link (Duanmu and Guney Citation2013).

22 Some studies argue that trade in differentiated and homogeneous products alike benefit from the contract enforcement channel whereas trade in the former products benefit more from the information channel than trade in the latter (Vézina Citation2012; Felbermayr, Jung, and Toubal Citation2010; Rauch and Trindade Citation2002). However, the contract enforcement channel is arguably stronger for differentiated products since it is more difficult to negotiate, enter into, and ensure enforcement of contracts regarding complex products, something which is hinted at by the evidence in Vézina (Citation2012). In addition, the information channel captures much beyond the specific product, e.g. business culture, which explains why it may not be much stronger for differentiated products.

23 Rauch (Citation2001) refers to Saxenian (Citation2002) who documents how ethnic networks have facilitated offshoring to India.

24 These features are commonly operationalized as the number of traded x-digit products and the average value per product.

25 See Cuadros, Martín-Montaner, and Paniagua (Citation2019), for an overview of the migration and FDI literature, focusing on high-skilled migration.

26 Besides incorporating the information effect of migration on FDI, this model allows for temporary emigration, which is balanced by return migration.

27 Hence, the summary is not the result of a meta-analysis. The same applies for additional tables that summarize the results of previous empirical studies.

28 We found 22 macro-level studies that have analyzed migration and FDI. Unlike the macro-level studies that looked at trade in manufactures, which found a stronger influence on imports relative to exports overall, the evidence of the FDI studies suggests that migration tends to have a stronger influence on outgoing FDI than on investment inflows. On average, the migration elasticity with respect to outgoing FDI to immigrant source countries is 0.33, while the corresponding elasticity with respect to incoming FDI is 0.15.

29 Most recently, promising avenues for studying causality from immigration to trade and FDI, using sub-national data, have come from exploiting exogenous events (Bahar et al. Citation2018; Parsons and Vézina Citation2018; Steingress Citation2018; Cohen, Umit, and Malloy Citation2017). For example, Parsons and Vézina (Citation2018) use information on U.S. immigration of the Vietnamese Boat People in the 1970s, while the U.S. had a lengthy trade embargo on Vietnam, and the subsequent removal of the embargo.

30 This line of research largely confirms the macro-level finding of a pro-FDI role of migrants. E.g., Mayda et al. (Citation2019) use quasi-random allocation of refugees in the host country as well as a natural experiment to demonstrate the role of refugees in promoting FDI, in the medium to long term, to their country and region of origin.

31 Two recent studies, in this vein, use Danish firm-level data and municipal shares of foreign-born, finding that foreign-born increase the probability to offshore to a foreign destination, with one of the studies finding a stronger result for foreign-born with more education or in more senior positions (Moriconi, Peri, and Pozzoli Citation2020; Olney and Pozzoli Citation2019).

32 Immigration held center stage prior to the 2016 UK EU membership referendum, and immigration was the single biggest issue for British voters: more than half (55%) said that they thought the government should have more control over who is granted entry into the UK, even if this meant the UK leaving the EU (Ipsos MORI Citation2016).

References

- Aguiar, A., T. Walmsley, and J. Abrevaya. 2007. “Effects of Bilateral Trade on Migration Flows: The Case of the United States.” Paper presented at the 10th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, Purdue University, USA.

- Aleksynska, M., and G. Peri. 2014. “Isolating the Network Effect of Immigrants on Trade.” The World Economy 37: 434–455.

- Andrews, M., T. Schank, and R. Upward. 2017. “Do Foreign Workers Reduce Trade Barriers? Microeconomic Evidence.” The World Economy 40: 1750–1774.

- Aroca, P., and W. F. Maloney. 2005. “Migration, Trade, and Foreign Direct Investment in Mexico.” The World Bank Economic Review 19: 449–472.

- Artal-Tur, A., A. F. Ghoneim, and N. Peridy. 2015. “Proximity, Trade and Ethnic Networks of Migrants: Case Study for France and Egypt.” International Journal of Manpower 36: 619–648.

- Bahar, D., A. Hauptmann, C. Özgüzel, and H. Rapoport. 2018. “Let Their Knowledge Flow: The Effect of Returning Refugees on Export Performance in the Former Yugoslavia.” CESifo Working Paper No. 7371.

- Bahar, D., and H. Rapoport. 2018. “Migration, Knowledge Diffusion and the Comparative Advantage of Nations.” The Economic Journal 128: F273–F305.

- Bastos, P., and J. Silva. 2012. “Networks, Firms, and Trade.” Journal of International Economics 87: 352–364.

- Bernard, A. B., J. Eaton, J. B. Jensen, and S. Kortum. 2003. “Plants and Productivity in International Trade.” American Economic Review 93: 1268–1290.

- Bernard, A. B., S. J. Redding, and P. K. Schott. 2007. “Comparative Advantage and Heterogeneous Firms.” Review of Economic Studies 74: 31–66.

- Bhattacharya, U., and P. Groznik. 2008. “Melting Pot or Salad Bowl: Some Evidence from U.S. Investments Abroad.” Journal of Financial Markets 11: 228–258.

- Blanes, J. V. 2010. “The Link between Immigration and Trade in Developing Countries.” Working Papers 10-07, Asociación Española de Economía y Finanzas Internacionales.

- Borjas, G. J. 1987. “Self-selection and the Earnings of Immigrants.” American Economic Review 77: 531–553.

- Bowen, H. P., and J. P. Wu. 2013. “Immigrant Specificity and the Relationship between Trade and Immigration: Theory and Evidence.” Southern Economic Journal 80: 366–384.

- Buchardi, K. B., T. Chaney, and T. A. Hassan. 2019. “Migrants, Ancestors and Foreign Investments.” The Review of Economic Studies 86: 1448–1486.

- Carbaugh, R. J. 2007. “Is International Trade a Substitute for Migration?” Global Economy Journal 7.

- Cardoso, M., and A. Ramanarayanan. 2019. “Immigrants and Exports: Firm-Level Evidence from Canada.” Department of Economics Research Report Series No. 2.

- Casella, A., and J. E. Rauch. 1998. “Overcoming Informational Barriers to International Resource Allocation: Prices and Group Ties.” NBER Working Paper, WP 6628.

- Casella, A., and J. E. Rauch. 2002. “Anonymous Market and Group Ties in International Trade.” Journal of International Economics 58: 19–47.

- Chaney, T. 2014. “The Network Structure of International Trade.” American Economic Review 104: 3600–3634.

- Clerides, S. K., S. Lach, and J. R. Tybout. 1998. “Is Learning by Exporting Important? Micro-Dynamic Evidence from Colombia, Mexico, and Morocco.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113: 903–947.

- Cohen, L., G. Umit, and C. Malloy. 2017. “Resident Networks and Corporate Connections: Evidence from World War II Internment Camps.” The Journal of Finance 72: 207–248.

- Combes, P.-P., M. Lafourcade, and T. Mayer. 2005. “The Trade-Creating Effects of Business and Social Networks: Evidence from France.” Journal of International Economics 66: 1–29.

- Cuadros, A., J. Martín-Montaner, and J. Paniagua. 2016. “Homeward Bound FDI: Are Migrants a Bridge Over Troubled Finance?” Economic Modelling 58: 454–465.

- Cuadros, A., J. Martín-Montaner, and J. Paniagua. 2019. “Migration and FDI: The Role of Job Skills.” International Review of Economics & Finance 59: 318–332.

- Duanmu, J.-L., and Y. Guney. 2013. “Heterogeneous Effect of Ethnic Networks on International Trade of Thailand: The Role of Family Ties and Ethnic Diversity.” International Business Review 22: 126–139.

- Dunlevy, J. A., and W. K. Hutchinson. 1999. “The Impact of Immigration on American Import Trade in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 59: 1043–1062.

- Evenett, S. 2020. “Sickening Your Neighbor: Export Restraints on Medical Supplies During a Pandemic.” VoxEU, CEPR.

- Faustino, H. C., and J. Peixoto. 2013. “Immigration, Trade Links: Evidence from Portugal.” Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 26: 155–170.

- Federici, D., and M. Giannetti. 2010. “Temporary Migration and Foreign Direct Investment.” Open Economies Review 21: 293–308.

- Felbermayr, G., V. Grossmann, and W. Kohler. 2015. “Migration, International Trade and Capital Formation: Cause or Effect?” In Handbook of the Economics of International Migration, Vol. 1B, edited by B. R. Chiswick and P. W. Miller, 913–1025. North-Holland: Elsevier.

- Felbermayr, G. J., B. Jung, and F. Toubal. 2010. “Ethnic Networks, Information, and International Trade: Revisiting the Evidence.” Annals of Economics and Statistics 97/98: 41–70.

- Flisi, S., and M. Murat. 2011. “The Hub Continent. Immigrant Networks, Emigrant Diasporas and FDI.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 40: 796–805.

- Foley, C. F., and W. R. Kerr. 2013. “Ethnic Innovation and U.S. Multinational Firm Activity.” Management Science 59: 1529–1544.

- Fontagné, L. 1999. “Foreign Direct Investment and International Trade: Complements or Substitutes?” OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers 10/1999.

- Foster-McGregor, N., and O. Pindyuk. 2013. “Ethnic Networks and Services Trade.” Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Manuscript.

- Gao, T. 2003. “Ethnic Chinese Networks and International Investment: Evidence from Inward FDI in China.” Journal of Asian Economics 14: 611–629.

- Gaston, N., and D. R. Nelson. 2013. “Bridging Trade Theory and Labour Econometrics: The Effects of International Migration.” Journal of Economic Surveys 27: 98–139.

- Geddes, A., and J. Money. 2011. Mobility Within the European Union. Migration, Nation States, and International Cooperation. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Genc, M., M. Gheasi, P. Nijkamp, and J. Poot. 2011. “The Impact of Immigration on International Trade: A Meta-Analysis.” Norface Discussion Paper 2011/020.

- Golob Šušteršič, T., and K. Zajc Kejžar. 2020. “The Role of Skilled Migrant Workers in FDI-Related Technology Transfer.” Review of World Economics 156: 103–132.

- Good, M. 2013. “Gravity and Localized Migration.” Economics Bulletin 33: 2445–2453.

- Gopinath, G. 2020. “The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression.” IMF. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/.

- Gould, D. 1994. “Immigrant Links to the Home Country: Empirical Implications for U.S. Bilateral Trade Flows.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 76: 302–316.

- Greif, A. 1993. “Contract Enforceability and Economic Institutions in Early Trade: The Maghribi Traders’ Coalition.” The American Economic Review 83: 525–548.

- Grossman, G. M., and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2008. “Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring.” American Economic Review 98: 1978–1997.

- Grossman, G. M., and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2012. “Task Trade between Similar Countries.” Econometrica 80: 593–629.

- Handley, K., and N. Limao. 2013. “Does Policy Uncertainty Reduce Economic Activity? Insights and Evidence from Large Trade Reforms.” VoxEU, CEPR.

- Hatton, T. J., and J. G. Williamson. 2005. “What Fundamentals Drive World Migration?” In Poverty, International Migration and Asylum, edited by G. Borjas, and J. Crisp, 15–38. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hatzigeorgiou, A., P. Karpaty, R. Kneller, and M. Lodefalk. 2017. “Do Immigrants Spur Offshoring? Firm-Level Evidence.” Working Paper, 282. Ratio Institute.

- Hatzigeorgiou, A., and M. Lodefalk. 2015. “Trade, Migration and Integration – Evidence and Policy Implications.” The World Economy 38: 2013–2048.

- Hatzigeorgiou, A., and M. Lodefalk. 2016. “Migrants’ Influence on Firm-Level Exports.” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 16: 477–497.

- Hatzigeorgiou, A., and M. Lodefalk. 2019. “Migration and Servicification: Do Immigrant Employees Spur Firm Exports of Services?” The World Economy 42: 3368–3401.

- Head, K., and J. Ries. 1998. “Immigration and Trade Creation: Econometric Evidence from Canada.” The Canadian Journal of Economics 31: 47–62.

- Herander, M. G., and L. A. Saavedra. 2005. “Exports and the Structure of Immigrant-Based Networks: The Role of Geographic Proximity.” Review of Economics and Statistics 87: 323–335.

- Hijzen, A., and P. W. Wright. 2010. “Migration, Trade and Wages.” Journal of Population Economics 23: 1189–1211.

- Hiller, S. 2013. “Does Immigrant Employment Matter for Export Sales? Evidence from Denmark.” Review of World Economics 149: 369–394.

- Hiller, S. 2014. “The Export Promoting Effect of Emigration: Evidence from Denmark.” Review of Development Economics 18: 693–708.

- Hoekman, B. M., M. Fiorini, and A. Yildirim. 2020. “Export Restrictions: A Negative-Sum Policy Response to the Covid-19 Crisis.” EUI RSCAS Working Paper No. 23.

- IMO. 2019. World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Inzelt, A. 2008. “The Inflow of Highly Skilled Workers Into Hungary: A by-Product of FDI.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 33: 422–438.

- Ipsos MORI. 2016. Immigration One of the Biggest Issues for Wavering EU Referendum Voters. Accessed 5 November 2016. https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/immigration-one-biggest-issues-wavering-eu-referendum-voters.

- Ivanov, A. V. 2008. “Informational Effects of Migration on Trade.” Discussion Paper 42. University of Mannheim Center for Doctoral Studies in Economics.

- Javorcik, B. S., Ç Özden, M. Spatareanu, and C. Neagu. 2011. “Migrant Networks and Foreign Direct Investment.” Journal of Development Economics 94: 231–241.

- Johanson, J., and J.-E. Vahlne. 1977. “The Internationalization Process of the Firm—A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments.” Journal of International Business Studies 8: 23–32.

- Johanson, J., and J.-E. Vahlne. 2009. “The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership.” Journal of International Business Studies 40: 1411–1431.

- Koenig, P. 2009. “Immigration and the Export Decision to the Home Country.” PSE Working Papers 2009-31.

- Kohli, U. 2002. “Migration and Foreign Trade: Further Results.” Journal of Population Economics 15: 381–387.

- Kugler, M., and H. Rapoport. 2007. “International Labor and Capital Flows: Complements or Substitutes?” Economics Letters 94: 155–162.

- Law, D., M. Genç, and J. Bryant. 2013. “Trade, Diaspora and Migration to New Zealand.” The World Economy 36: 582–606.

- Layard, R. 1992. East-West Migration: The Alternatives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lewer, J. J., and H. Van den Berg. 2009. “Does Immigration Stimulate International Trade? Measuring the Channels of Influence.” The International Trade Journal 23: 187–230.

- Lin, F. 2011. “The pro-Trade Impacts of Immigrants: A Meta-Analysis of Network Effects.” Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies 4: 17–27.

- Lodefalk, M. 2016. “Temporary Expats for Exports: Micro-Level Evidence.” Review of World Economics 152: 733–772.

- Lopéz, R. A. 2009. “Do Firms Increase Productivity in Order to Become Exporters?” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71: 621–642.

- Lücke, M., and T. Stöhr. 2018. “Heterogeneous Immigrants, Exports and Foreign Direct Investment: The Role of Language Skills.” The World Economy 41: 1529–1548.

- Marchal, L., and C. Nedoncelle. 2017. “How Foreign-Born Workers Foster Exports.” Kiel Working Paper 2071.

- Markusen, J. R. 1983. “Factor Movements and Commodity Trade as Complements.” Journal of International Economics 14: 341–356.

- Markusen, J. R., and N. Trofimenko. 2009. “Teaching Locals New Tricks: Foreign Experts as a Channel of Knowledge Transfers.” Journal of Development Economics 88: 120–131.

- Martín-Montaner, J., F. Requena, and G. Serrano. 2014. “International Trade and Migrant Networks: Is It Really About Qualifications?” Estudios de Economía 41: 251–260.

- Massey, D. 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19: 431–466.

- Mayda, A. M., C. Parsons, H. Pham, and P.-L. Vézina. 2019. “Refugees and Foreign Direct Investment: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from US Resettlements.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 12860.

- McKenzie, D. 2007. “Paper Walls are Easier to Tear Down: Passport Costs and Legal Barriers to Emigration.” World Development 35 (11): 2026–2039.

- Melitz, M. J. 2003. “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity.” Econometrica 71: 1695–1725.

- Miroudot, S. 2020. “Reshaping the Policy Debate on the Implications of Covid-19 for Global Supply Chains.” Journal of International Business Policy 3: 430–442.

- Mitaritonna, C., G. Orefice, and G. Peri. 2017. “Immigrants and Firms’ Outcomes: Evidence from France.” European Economic Review 96: 62–82.

- Moriconi, S., G. Peri, and D. Pozzoli. 2020. “The Role of Institutions and Immigrant Networks in Firms’ Offshoring Decisions.” Canadian Journal of Economics 53: 1745–1792.

- Mundell, R. 1957. “International Trade and Factor Mobility.” American Economic Review 47: 321–335.

- Mundra, K. 2005. “Immigration and International Trade: A Semiparametric Empirical Investigation.” The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development 14: 65–91.

- Mundra, K. 2012. “Immigration and Trade Creation for the U.S.: The Role of Immigrant Occupation.” Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). IZA Discussion Paper No. 7073.

- Murat, M., and B. Pistoresi. 2009. “Emigrant and Immigrant Networks in FDI.” Applied Economics Letters 16: 1261–1264.

- Nathan, M. 2014. “The Wider Economic Impacts of High-Skilled Migrants: a Survey of the Literature for Receiving Countries.” IZA Journal of Migration 3: 4–20.

- Nijkamp, P., M. Gheasi, and P. Rietveld. 2011. “Migrants and International Economic Linkages: A Meta-Overview.” Spatial Economic Analysis 6: 359–376.

- Olney, O. W., and D. Pozzoli. 2019. “The Impact of Immigration on Firm-Level Offshoring.” Review of Economics and Statistics.

- Panagariya, A. 1992. “Factor Mobility, Trade and Welfare.” Journal of Development Economics 39: 229–245.

- Parrotta, P., D. Pozzoli, and D. Sala. 2016. “Ethnic Diversity and Firms’ Export Behavior.” European Economic Review 89: 248–263.

- Parsons, C., and P.-L. Vézina. 2018. “Migrant Networks and Trade: The Vietnamese Boat People as a Natural Experiment.” The Economic Journal 128: F210–F234.

- Partridge, J., and H. Furtan. 2008. “Immigration Wave Effects on Canada's Trade Flows.” Canadian Public Policy 34: 193–214.

- Pennerstorfer, D. 2016. “Export, Migration and Costs of Trade: Evidence from Central European Firms.” Regional Studies 50: 848–863.

- Peri, G., and F. Requena-Silvente. 2010. “The Trade Creation Effect of Immigrants: Evidence from the Remarkable Case of Spain.” Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D’économique 43: 1433–1459.

- Peri, G., K. Shih, and C. Sparber. 2015. “STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities.” Journal of Labor Economics 33: S225–S255.

- Peri, G., and C. Sparber. 2009. “Task Specialization, Immigration and Wages.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1: 135–169.

- Rauch, J. E. 1991. “Reconciling the Pattern of Trade with the Pattern of Migration.” The American Economic Review 81: 775–796.

- Rauch, J. E. 1996. “Trade and Search: Social Capital, Sogo Shosha, and Spillovers.” NBER Working Paper, WP 5618. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Rauch, J. E. 1999. “Networks Versus Markets in International Trade.” Journal of International Economics 48: 7–35.

- Rauch, J. E. 2001. “Business and Social Networks in International Trade.” Journal of Economic Literature 39: 1177–1203.

- Rauch, J. E., and A. Casella. 2003. “Overcoming Informational Barriers to International Resource Allocation: Prices and Ties.” The Economic Journal 113: 21–42.

- Rauch, J. E., and V. Trindade. 2002. “Ethnic Chinese Networks in International Trade.” Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 116–130.

- Rauch, J. E., and J. Watson. 2004. “Network Intermediaries in International Trade.” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 13: 69–93.

- Río, A. M. D., and S. Thorwarth. 2009. “Tomatoes or Tomato Pickers? Free Trade and Migration between Mexico and the United States.” Journal of Applied Economics 12: 109–135.

- Sangita, S. 2013. “The Effect of Diasporic Business Networks on International Trade Flows.” Review of International Economics 21: 266–280.

- Saxenian, A. 2002. “Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant High-Growth Entrepreneurs.” Economic Development Quarterly 16: 20–31.

- Schiff, M. 2006. “Substitution in Markusen’s Classic Trade and Factor Movement Complementarity Models.” Policy Research Working Paper 3974. World Bank.