?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We investigate the impact of China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on the export sophistication of countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Through an examination of data spanning from 2010 to 2015, our findings reveal that China’s OFDI significantly enhances export sophistication in host countries, with a more pronounced effect observed in relatively poor BRI nations. However, the positive correlation between China’s OFDI and export sophistication diminishes in host countries characterized by elevated productivity levels. Utilizing a structural equation model, we identify host country productivity as a crucial mediating factor. The indirect technology spillover effects of China’s OFDI, facilitated through increased productivity, account for approximately 39% of their overall impact on export sophistication. Furthermore, we delineate threshold effects of productivity for China’s OFDI, demonstrating substantial positive effects in host countries with a GDP per capita below the first threshold (approximately US$1,141) or within the range of the first and second thresholds (around US$7,115). Upon consideration of these thresholds, distinctions in the effects of China’s OFDI between BRI and non-BRI host countries diminish. Our analysis underscores that the favorable influence of China’s OFDI extends beyond the BRI, providing benefits to low and middle-income countries globally.

1. Introduction

Since the early 1990s, multinational corporations (MNCs) have reshaped global production processes, fostering an integrated global economy. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and a surge in bilateral free trade agreements in the late 1990s further accelerated international trade and investment (Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzalez Citation2015; Peng et al. Citation2020).Footnote1 China, a key player since joining the WTO in 2001, has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a traditional exporter to a global manufacturing and investment powerhouse. China’s exports grew over fivefold between 1992 and 2007, outpacing national GDP growth. Now the world’s second-largest economy, China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) stock skyrocketed from 0.4% in 2002 to 6.7% in 2021, totaling $2.8 trillion and securing the third position in global investment stocks (Ministry of Commerce Citation2022).

This surge in international trade and OFDI reflects not just quantitative expansion but also a swift transformation in export and investment structures. China shifted from labor-intensive to capital and technology-intensive sectors, defying expectations based on national productivity levels (Li et al. Citation2022). Rodrik (Citation2006) highlights China’s exception, displaying advanced export sophistication compared to its national productivity level. Xu and Lu (Citation2009), among others, observe China’s export assortment aligning progressively with that of the world’s most developed economies, encapsulating the ‘China is special’ phenomenon in export sophistication studies (Jarreau and Poncet Citation2012; Xu Citation2010).

The anomaly of elevated export sophistication in China is attributed to the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) by MNCs, particularly in high-tech industries and developed regions. Foreign firms accounted for 82% of processing exports and 91% of high-tech processing exports in 2007 (Jarreau and Poncet Citation2012). Regional disparities in export capability, not fully captured by China’s average income, underscore the role of advanced MNCs in elevating China’s overall export sophistication beyond its apparent lower average productivity (Xu Citation2010).

An additional facet of the ‘China is special’ phenomenon lies in how export upgrading contributes to economic growth. Rodrik (Citation2006) emphasizes the significance of China’s export of higher-income products for its rapid growth, aligning with Hausman et al.’s (Citation2007) assertion that regions specializing in sophisticated goods experience accelerated growth. This prompts the question: can other nations emulate China’s model of high export sophistication and rapid economic growth, rooted in processing trade and foreign investment? This paper aims to examine the impact of Chinese OFDI on the export sophistication of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries, considering the distinct ‘China is special’ aspect. Notably, limited previous literature has investigated the potential replication of China’s successful approach within the BRI framework.

This paper makes two important contributions to existing literature. First, while various aspects of the BRI have been explored, few studies have delved into the impact of China’s OFDI on the economic performance of BRI countries, considering the nuanced perspective of the ‘China is special’ issue in export sophistication. Employing a Structural Equation Model (SEM), we aim to provide fresh insights into the diffusion of technology and knowledge through China’s OFDI within domestic firms, using host countries’ productivity as mediators. Second, China can leverage its investment potential to assist developing BRI countries in enhancing their capacity to export sophisticated goods compared to their developed counterparts. We calculate the export sophistication index across various export goods, enabling exploration of the moderating effects of the BRI initiative and host countries’ productivity in an internationally standardized context. This pioneering effort addresses recent calls for research on the influence of export sophistication among BRI countries within the global trade and production system (Panibratov et al. Citation2022).

2. Literature review and hypotheses setting

2.1. Background of BRI

In the years following China’s WTO entry, the global impact of its investments was minimal (Kang, Peng, and Anwar Citation2023). The ‘Going out Strategy’ emerged in the early 2000s, encouraging Chinese enterprises to invest abroad and engage in regional trade partnerships (Liu et al. Citation2017). The BRI, launched in 2013, aimed to strengthen trade and investment partnerships in Central Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Africa, and Central-East Europe. Covering 74 economies with over 4 billion people, BRI represents 60% of the world population, accounting for $21 trillion, 65% land-based and 30% maritime-based global production values, and 30% of world trade (Swaine Citation2015). BRI extends China’s ‘Going out Strategy’ to sustain economic growth through closer cooperation with regional partners (Huang Citation2016).

BRI focuses on trade and investment facilitation, policy coordination, infrastructure development, financial integration, and people-to-people connectivity (Woodworth and Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020). Initiatives like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), New Development Bank (NDB), and Silk Road Fund (SRF) support BRI goals. China’s OFDI to BRI countries nearly quadrupled from 2010 to 2015, surpassing the 57% growth to non-BRI countries (Kang, Peng, and Anwar Citation2023; UN Citation2018).

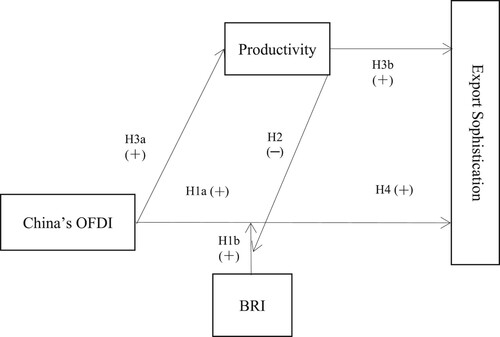

BRI, coupled with China’s OFDI, plays a pivotal role in upgrading the export capability of partner countries, influencing both upstream and downstream export sophistication (Fung et al. Citation2018; Sun, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2024). The rapid increase in China’s OFDI to BRI countries facilitates resource and technology spillover, potentially enhancing overall export sophistication and productivity. However, BRI countries face a productivity gap compared to non-BRI nations, raising questions about the potential benefits of participation and emulation of China’s successful model. This raises some interesting questions. Specifically, can less developed countries enhance their standard of living by participating in the BRI and emulating the successful Chinese model built on processing trade and foreign direct investment from China? Can China’s OFDI enhance the economic performance of BRI countries by elevating their capacity to produce sophisticated goods for export? To focus on these issues, we have formulated a conceptual model presented in Figure .

2.2. China’s OFDI in BRI countries

FDI is recognized for driving economic growth, contributing to capital formation, and enhancing the quality of the capital stock. China’s OFDI, viewed through the lens of knowledge spillover effects, can positively influence export sophistication in host countries. The ‘China is special’ phenomenon, linking export sophistication in China to the proportion of wholly foreign-owned enterprises from advanced OECD countries, further emphasizes the potential impact of China’s OFDI (Xu and Lu Citation2009).

Horizontal and vertical FDI channels influence technology and knowledge diffusion. Horizontal FDI improves domestic firm productivity through linkages with local intra-industry firms, fostering spillover effects (Lu, Tao, and Zhu Citation2017). On the other hand, vertical FDI, occurring across industries, enhances productivity through inter-industry channels. The ‘China is special’ phenomenon extends to BRI countries, where the impact of China’s OFDI on export sophistication may vary based on the level of economic development (Golo Citation2023). Drawing on this discussion, we have 2 hypotheses, as depicted in Figure , as follows:

H1a: China’s OFDI has a significantly positive impact on the export sophistication of host countries.

H1b: China’s OFDI may exert a stronger positive impact on the export sophistication of BRI countries compared to countries not participating in the BRI.

H2: The impact of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of high-income BRI countries is relatively weaker.

2.3. Mediating effects of host country productivity

China’s OFDI not only directly enhances export sophistication through foreign investment and processing trade but also indirectly fosters it through technology and knowledge spillovers, boosting domestic productivity in host countries (Anwar and Sun Citation2018; Mallick and Zhang Citation2022). The effectiveness of these spillovers depends on host countries’ absorptive capacity, influenced by factors like technical disparity, human capital, market maturity, and institutional quality (Fan, Li, and Pan Citation2019). However, when China’s OFDI gains a significant market share in host countries or when there is a substantial technological gap, its impact on domestic productivity may be limited (Wang and Wei Citation2007). Moreover, joint ventures may not always lead to productivity and export sophistication gains. Therefore, understanding the mediating role of productivity is crucial to discern the direct and indirect effects of China’s OFDI on export sophistication.

H3a: China’s OFDI can enhance the productivity levels of host countries.

H3b: China’s OFDI has both direct and indirect positive effects, mediated by productivity, on the export sophistication of host countries.

2.4. The nonlinear effect of China’s OFDI

China’s OFDI towards BRI countries has surged dramatically, outpacing investments in non-BRI nations by nearly 300% from 2010 to 2015 (Kang, Peng, and Anwar Citation2023; UN Citation2018). This prompts an examination of the diverse impacts of China’s OFDI on host countries’ export sophistication. Barrios, Görg, and Strobl (Citation2005) highlight two effects of foreign direct investment (FDI): a competition effect that may deter domestic firm entry and positive market externalities that foster local industry development. Empirical studies reveal that while initial competition effects may deter domestic firms, they are offset by later positive externalities (Luong et al. Citation2017). Xu and Lu (Citation2009) find that only FDI from advanced economies enhances export sophistication for China’s foreign-owned firms. Conversely, Harding and Javorcik (Citation2011) find ambiguous effects of FDI on export sophistication in high-income economies. Recent research suggests a nonlinear relationship between FDI and technology diffusion (Xiao and Park Citation2017). China’s OFDI is more likely to benefit lower-income host countries by fostering local suppliers in upstream sectors through positive market externalities. However, in richer host countries, OFDI may deter domestic firm entry, leading to limited backward linkages. Moreover, the relationship between China’s OFDI and host countries’ export sophistication may be nonlinear, varying across different levels of host country productivity (Li and Tanna Citation2018). Therefore, we have a hypothesis as follows:

H4: The effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication of host countries depends on threshold values of host country productivity levels.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Empirical specification

To estimate the effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication of host countries, following Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007), we apply a log-linear model as follows:

(1)

(1) where the dependent variable is logarithm of export sophistication (

) of host country

in year

as in Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007).

is the logarithm of China’s real OFDI. BRI is a dummy variable of countries participating the Belt and Road Initiative.

is a vector of host country control variables, which following Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007), and Mallick and Zhang (Citation2022) include productivity (logarithm of real GDP per capita,

), human capital (enrollment proportion at secondary level education,

), infrastructure

, FDI (

, % GDP), institutional quality (

), cultural distance (

), labor force (

, % population) and the economic structure (

, a ratio of an industrial sector to a service sector);Footnote2

is a vector of 7 dummies to control 8 regional fixed effects (k = 1 … 7, East Asia & Pacific as the baseline region);

is a vector of dummies for years of 2010–2015 to capture the aggregated time dynamics of the world economy, and

is the usual error term.

Because of the dependent and the main explanatory variables are in logarithms, the corresponding coefficients ( and

) are estimated elasticities of export sophistication. We also consider alternative measures of export sophistication. Given that we are estimating the macro-level spillover effects of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of host countries, Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007) measure of export sophistication for host countries, which relies on global productivity levels, becomes more relevant within an internationally comparative perspective.

We use the weighted ordinary least square (OLS) where the population of the host countries is used to calculate the weights. As the potential endogeneity problem based on the simultaneity and reverse causality between Chinese OFDI and the export sophistication of host countries is concerned, we apply the GMM technique on the equation using lagged values of China’s OFDI as IVs. We also use a BRI country dummy and its interactions with China’s OFDI () to estimate the moderating effect of the BRI on the relationship between China’s OFDI and export sophistication (see H1a-b in Figure ) in equation Equation(1)

(1)

(1) .

To estimate the moderating effects of host country’s productivity on China’s OFDI in BRI countries (see H2 in Figure ), the interaction term (BRI*lnrofdiit*lnrgdppc) is included in equation Equation(2)(2)

(2) as follows:

(2)

(2) where the dependent variable remains the logarithm of the export sophistication (

) of the host country. The vector of control variables for host countries, Xit, remains unchanged. Previous studies, such as Zhang et al. (Citation2014), have identified productivity as a crucial channel through which Chinese OFDI enhance the export sophistication of BRI countries. To analyze the promotional mechanism of China’s OFDI, we estimate the mediating effect of host countries’ productivity on Chinese OFDI within a structural equation model (SEM) as follows.

(3a)

(3a)

(3b)

(3b) In the first equation (3a) of the SEM, the dependent variable is the logarithm of real GDP per capita (

). The primary explanatory variable is the logarithm of China’s real OFDI (

). The vector of control variables for host countries,

remains consistent as outlined earlier. By estimating the spillover effects of China’s OFDI on the host country’s productivity, we then utilize the second equation (3b) to simulate the direct and indirect impacts of China’s OFDI on export sophistication through the mediating mechanism of the host country’s productivity (as highlighted by H3a–b in Figure ).

The possible non-linear relationship between China’s OFDI and export sophistication of host countries must be considered. We use a double-threshold model, which allows the effect of China’s OFDI to vary across the regions of the threshold variable (real GDP per capita, ) as follows:

(4a)

(4a)

(4b)

(4b)

(4c)

(4c) where real GDP per capita of host countries (

) is used as the threshold variable, and

and

are the estimated threshold values.

To simplify the estimation, we regard the coefficients of BRI dummy () and control variables (

) as constants across the regions of productivity of host countries. Thus, only the constants (

,

, and

), the coefficients of China’s OFDI (

,

, and

) and its interactions with BRI dummy (

,

, and

) are allowed to vary across the regions of productivity of host countries (see H4 in Figure ).

3.2. Data description and measurement

3.2.1. The dependent variable

Following Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007), we calculate export sophistication (EXPY) using a two-step approach for each host country over the 2010–2015 period.

First, an index of product sophistication (PRODY) is constructed. This index is a weighted average of the GDPs per capita of countries exporting a given product and thus represents the income level associated with that product. Countries are indexed by i and products by j. Total exports of all products by a country i are . We also denote the GDPs per capita of country i by Yi, which has been adjusted to 2010 US$ prices using the GDP deflators provided by the World Bank. The productivity level associated with product j, i.e. index of product j sophistication (

), is calculated as follows:

(5)

(5) The revealed comparative advantage of each country i in export product j (RCAij), i.e.

is used as weights. The numerator of the weight,

, is the value-share of the product j in the country’s overall export basket. The denominator of the weight,

, aggregates the value-shares across all countries exporting the product j. The reason for using revealed comparative advantage as a weight is to ensure that country size (also export size) does not distort the ranking of the products exported. The commodities exported by relatively rich countries are ranked higher than those exported by poor countries. We use 260 3-digit products in SITC 3.0 (j = 260) exported by 183 countries (including China, i = 183) from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN COMTRADE Citation2018) to calculate the export sophistication index for each product (

).

Second, export sophistication of country i () is defined as the weighted average product sophistication of country i’s export basket. The weights are the value-share of the product j in the country’s overall export basket,

. Thus, export sophistication of country i is as follows:

(6)

(6) Descriptive statistics of the dependent and explanatory variables, and control variables are shown in Table .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of all variables, 2010–2015 (1296 observations).

3.2.2. The main explanatory variable

Logarithm of China’s real OFDI () in 2010 US$ is the main explanatory variable. China’s OFDI in millions of US dollars was converted into 2010 real values using the GDP deflator provided by the World Bank.

3.2.3. Control variables

The early work of Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007) identifies some fundamental determinants of the level of export sophistication across countries. They argue that export sophistication is highly correlated with per capita GDP, human capital, and the size of the labor force. GDP per capita and human capital are expected to be positively associated with export sophistication, but a large increase in the size of the labor force may promote labor-intensive technology, which could decrease the level of export sophistication. Existing studies highlight the importance of the economic, institutional, and cultural environment, such as infrastructure, political stability, cultural distance, and industrialization, and overall macroeconomic and trade policy climate. Therefore, we also include these control variables in our estimation.

Productivity of each country is measured by the logarithm of real GDP per capita () in 2010 US dollars. In 2010, China’s real GDP per capita was US$4,560, ranking 120th among 217 economies and between the 25th percentile (around US$1,544) and the 50th percentile (around US$5,936). By the end of our sample year 2015, China’s real GDP per capita (in 2010 US$) was US$7,063, ranking 92nd among 217 economies and between the 50th and 75th percentiles (US$19,839). This indicates that China’s productivity improved rapidly during the sample period and surpassed the median level in terms of GDP per capita. Therefore, the sample period 2010–2015, during which China transitioned from a low-middle-income country to a middle-high-income country, represents a unique semi-natural societal experiment for studying the effect of China’s OFDI on its host countries.

The human capital (edu2) of host countries reflects the absorptive capacity of spillover effects from imports and FDI from China. We use the enrollment ratio of secondary-level education as a proxy for host country human capital. Data on this variable were sourced from the World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2018a).

Infrastructure (infra) is considered an important environmental factor for FDI-related spillovers. We use principal component methods to construct a single factor, which is a composite measure of infrastructure. This composite factor is constructed using exploratory factor analysis on six infrastructure-related variables in 216 host countries and China. The variables used are railway density (total railway kilometers/country area), the logarithm of air transport freight (million ton-km), individuals using landline phones (% of the population), individuals using a mobile phone (% of the population), individuals using the internet (% of the population), and fixed broadband subscriptions (% of the population). Data on these variables were sourced from the World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2018a). In Table , the infrastructure variable (infra) varies in the range of −1.06 to 3.51, with higher values indicating a higher quality of infrastructure in host countries.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in host countries as a proportion of GDP is also sourced from the World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2018a). This variable captures the degree of openness of host countries. Institutional quality (WGI) measure was constructed using the principal component methodology. Specifically, six social and political governance-related variables (government effectiveness, regulatory quality, control of corruption, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, voice and accountability, and the rule of law) were used to construct a measure of institutional quality. The data were sourced from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank Citation2018b). In Table , the composite measure of institutional quality varies from −2.28 to 1.93, with higher values indicating higher institutional quality in host countries.

Cultural distance (CD) is another control variable, which is important in the context of China’s FDI. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries are culturally similar to China, so the cultural distance from China is minimal in the ASEAN countries. However, China’s cultural distance with Central and Eastern Europe and Western Asian countries is relatively large. We measure the cultural distance index (CD) using six cultural dimensions highlighted by Hofstede, including power distance, individualism and collectivism, masculinity and femininity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term and short-term, and indulgence and restraint. In Table , the cultural distance index varies from 0.16 to 8.16, with higher values indicating a higher cultural distance of host countries from China, which reflects weaker absorptive capacity and spillovers from China’s FDI.

We use the labor force as a proportion of the population (LAB) and the industrial sector-to-services sector ratio (INDSERV) to capture the economic structure of host countries. BRI country dummy and year dummies are also included in our regression equation. Finally, the population of host countries is used as weights in all regressions.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Baseline results

The baseline estimation results are presented in columns 1–3 of Table . The loglinear estimation results in column 1 indicate that a 100% increase in China’s FDI increases host countries’ export sophistication levels by about 3.6%. This aligns with four well-known channels through which FDI enhances domestic productivity in the host country: imitation, skills acquisition, competition, and export. The replication of China’s successful model by investing in a foreign host country involves emulating the processing trade, acquiring and enhancing skills, and subsequently exporting more sophisticated goods (Amiti and Freund Citation2010). The baseline results support Hypothesis 1a.

Table 2. China’s OFDI and the export sophistication of host countries, 2010–2015.

Including the control variables of BRI dummy and productivity of host countries, the estimated results in column 2 show that a 100% increase in China’s OFDI increases host countries’ export sophistication levels by about 1%. As found by Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik (Citation2007), national productivity has significantly positive effect on export sophistication as a 100% increase in host countries’ productivity can increase its export sophistication levels by about 14.2% in column 2. Moreover, the export sophistication of BRI countries is found about 17.5% higher than those countries not participating the BRI. It is consistent with the importance of the BRI countries in global production and trade (Swaine Citation2015) as well as the incongruity between export structure and developmental stage like the ‘China is special’ phenomenon (Jarreau and Poncet Citation2012; Xu Citation2010). In column 3, all control variables have been included in the estimation, the significantly positive effects of China’s OFDI, host country’s productive and BRI dummy do not change much, suggesting the stability of our estimation results to support Hypothesis 1a.

4.2. Hypothesis testing under BRI

We now consider the effects of China’s OFDI under BRI. Estimation results using equation Equation(1)(1)

(1) , including the interaction of China’s OFDI and BRI dummies, are reported in columns 4 of Table . These results can be used to test Hypothesis 1b.

The estimated results presented in column 4 show that the effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication is insignificant in host countries not participating in BRI. However, the estimated coefficient of the interaction with BRI dummies is statistically significant and positive (1.5%). The estimated positive effect of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of BRI countries is notably higher in countries not participating in BRI, supporting the positive moderating effect of BRI on China’s OFDI as posited in Hypothesis 1b.

As discussed earlier, China’s OFDI exerts positive effects through imitation, skills acquisition, and exports. However, it also leads to competitive and crowding-out effects on domestic producers in host countries. It is well-known that the competition effect of OFDI may hinder the entry of domestic firms, reducing the positive market externalities that foster the development of local industries. The full model estimation results using equation Equation(2)(2)

(2) , which includes interaction terms involving the BRI dummy, China’s OFDI and productivity of host countries, are shown in column 5 of Table . These results can be used to test Hypotheses 2.

For extremely poor BRI countries, a 100% increase in China’s OFDI increases the level of export sophistication by about 9.1% higher than in host countries not participating in BRI (insignificant), thus supporting Hypothesis 1b. This positive marginal effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication of BRI countries would decline by 0.8% as the productivity levels of host BRI countries increases by 100%. As the average productivity of BRI countries increases, the positive effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication declines. China’s OFDI improves the export sophistication of poor BRI countries more than that of rich BRI countries. The negative moderating effect of productivity in Hypothesis 2 is supported as low-income BRI countries can benefit more from China’s OFDI than their relatively rich BRI counterparts.

Additionally, as the productivity of BRI host countries increases from 0 to the highest level of the full sample (12.16 in Table ), the export sophistication of BRI countries decreases by about 9.728% (calculated as −0.8% * 12.16). This suggests that China’s OFDI leads to over-competition in the domestic market and could have a significantly negative effect (−0.628% = 9.1% – 9.728%) in host countries. This finding aligns with the argument regarding the non-linear relationship between competition and innovation in foreign investment (Luong et al. Citation2017). The complexity of China’s OFDI under BRI, exhibiting both positive and negative effects moderated by productivity, underscores the necessity for applying the threshold model in this study.

Regarding control variables, in line with existing literature predictions, export sophistication is closely related to the productivity levels of host countries. Human capital and institutional quality positively associate with export sophistication, while the labor force and cultural distance negatively associate with it. Surprisingly, the infrastructure of host countries has a significantly negative effect on their export sophistication. This may be because the infrastructure variable mainly proxies for information and communication technology (ICT) facilities, highly correlated with the productivity of host countries, with the positive effect already captured by GDP per capita.

4.3. Mediating effects of productivity

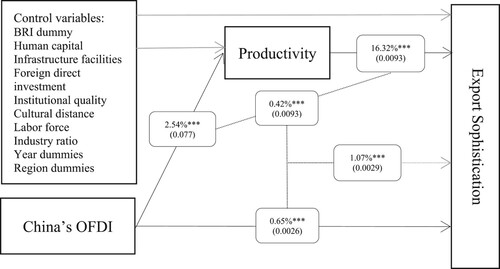

Productivity is considered the most crucial determinant of export sophistication across countries (Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik Citation2007). In this section, we discuss the mechanism of China’s OFDI on export sophistication through the channels of productivity, employing a formal structural equation model (SEM) in equations (3a) and (3b). The SEM results in Table demonstrate that the technology and knowledge spillovers of China’s OFDI promote domestic productivity in host countries by 2.54%, consistent with prior research (Anwar and Sun Citation2018; Mallick and Zhang Citation2022). Thus, Hypothesis 3a is supported.

Table 3. Mediating effect of productivity of host countries, using equation (3a)–(3b).

Furthermore, the total effects of China’s OFDI on export sophistication are decomposed into direct and indirect effects through the mediator of productivity (see Figure ). Results in columns 2–4 reveal that the indirect spillover effect through the productivity channel is based on China’s OFDI’s effect on domestic productivity (2.54%) and the effect of domestic productivity on export sophistication (16.32%), resulting in 0.42% (=2.54%*16.32%). Hypothesis 3b is fully confirmed by significantly positive direct (0.65%), indirect (0.42%), and total effects (1.07% = 0.65% + 0.42%, also see Figure ). The indirect technology and knowledge spillover effect represents about 39% (=0.42%/1.07%) of the total effects on export sophistication. Therefore, the technology and knowledge spillover through the productivity of host countries constitute a crucial mediating path for the impact of China’s OFDI on export sophistication.

4.4. Threshold model results

The non-linear relationship between the competition effect of foreign investment and domestic innovation and productivity has been considered by several studies such as Li and Tanna (Citation2018). In this section, we discuss the results of extending linear regression to allow the coefficients of China’s OFDI to differ across the productivity regions of host countries.Footnote3 Following literature such as Mallick and Zhang (Citation2022), productivity regions are identified by a threshold variable (lnrpgdp, the logarithm of real GDP per capita) being above or below a certain threshold value. Such a model may involve multiple thresholds, and hence, the optimal number of thresholds can be determined using the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQIC), and the sum of squared residuals of the model (SSR).

Table presents the estimation results for the optimal number of threshold values. When we chose two threshold values (the logarithm value of 7.04 or GDP per capita of US$1,141; and the logarithm value of 8.87 or GDP per capita of US$7,115), the default information criterion, BIC, yielded a maximum value of −3910.3. The other two information criteria, AIC (−4065.3) and HQIC (−4007.1), were also at their maximum values. The SSR of the two threshold values decreased from 53.73 to 52.37, which was the most significant reduction among all threshold values. This suggests that two optimal threshold values are present, thus supporting Hypothesis 4 (i.e. significant threshold effects exist). Hence, we used a double-threshold model to estimate the effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication across three regions of host country real GDP per capita as follows: (−∞, US$1,141], (US$1,141, US$7,115] and (US$7,115, +∞).

Table 4. Threshold value estimation and thresholds choices.

The double-threshold estimation results are presented in Table , revealing that a 100% increase in domestic productivity can increase the export sophistication of host countries by about 12.76%. Notably, the incremental effect on BRI countries remains statistically significant (5.62%), given that infrastructure facilities now have a significantly positive effect. As observed earlier, the labor force and cultural distance continue to show a negative association with export sophistication.

Table 5. Estimation of the double-threshold model.

Next, we focus on the threshold effects of China’s OFDI across regions of real GDP per capita. China’s real GDP per capita increased from US$4,560 in 2010 to US$7,063 in 2015. Additionally, China’s productivity surpassed the median per capita income, and the economy transformed from a middle-low-end manufacturing country to a middle-high-end investor country. The estimation results presented in panel 5a of Table reflect the positive effect of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of low-income countries, which is consistent with our findings in Table . Low-income countries in the first region of GDP per capita, less than US$1,141, are below the bottom quartile (US$1,544 in 2010) of the productivity distribution of all 217 countries included in our sample. As suggested by the vertical knowledge spillover literature (Fan, Li, and Pan Citation2019; Jarreau and Poncet Citation2012), China’s OFDI significantly increased the export sophistication level of low-income countries with forward linkages with China’s OFDI. A 100% increase in China’s OFDI can increase the export sophistication levels of low-income countries not participating in BRI by about 2.37%, and this effect does not vary much across BRI countries and those countries not participating BRI. Thus, for low-income countries, Hypothesis 1a still holds, but there is no evidence supporting Hypothesis 1b.

The estimation results pertaining to the effect of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of middle-income countries are presented in panel 5b of Table . Middle-income countries in the second region of GDP per capita, between US$1,141 and US$7,115, are around the median level (US$5,936 in 2010) and have similar productivity to China over the 2010–2015 period. As suggested by the knowledge horizontal spillover literature, China’s OFDI can significantly increase the export sophistication level of middle-income countries. Our estimation results show that a 100% increase in China’s OFDI can increase the export sophistication of middle-income countries not participating BRI by about 1.37%, and this effect is even higher in BRI countries (2.81% = 1.37% + 1.44%). Thus, both Hypothesis 1a and 1b are supported for middle-income countries.

Finally, the estimation results pertaining to the export sophistication of high-income countries are presented in panel 5c of Table . The effect of China’s OFDI on the export sophistication of high-income countries not participating in BRI through backward linkages with China’s OFDI is statistically insignificant (−0.19%). The incremental impact on BRI countries is also insignificant. Hence, neither Hypothesis 1a nor 1b is supported in high-income countries. The declining effect of China’s OFDI across the three regions also provides supporting evidence for Hypothesis 2, suggesting that China’s OFDI has a more significant positive threshold effect on the export sophistication of poor BRI countries compared to relatively rich BRI countries. There is no evidence of a preferential effect of China’s OFDI in low-income and high-income BRI host countries compared to host countries not participating in BRI. However, the middle-income BRI countries show a better absorptive capacity for the technology and knowledge diffusion of China’s OFDI, suggesting advantages of these countries in overcoming the spillover obstacles of large technology gaps and vertical inter-industry linkages (Anwar and Sun Citation2018; Fan, Li, and Pan Citation2019).

4.5. Accounting for potential endogeneity

The OLS estimation results could be biased by reverse causality between OFDI and export sophistication. It is possible that an increase in the export sophistication of host countries leads to an increase in FDI from China, which could create a stronger reverse causality effect for BRI countries due to their stronger trade, investment, and linkages with China. To address potential endogeneity, we used the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation technique, where lagged values of contemporaneous explanatory variables were used as instrumental variables (IVs). To simplify matters, we first only re-estimated the panel regression results for the first three columns of Table using GMM.

In column 1 of Table , GMM estimation results are presented with only OFDI as an explanatory variable, allowing for a direct comparison with the results in column 1 of Table . Under GMM estimation, the effect of OFDI on the export sophistication of host countries remains positive and statistically significant, albeit with a slightly higher estimated coefficient (5.3%). Hypothesis 1a is still supported. Comparing the GMM estimation results in columns 2 and 3 of Table with the non-GMM estimation in Table , we find that the impact of Chinese OFDI on export sophistication remains positive but becomes statistically insignificant (1.4% and 1.8%).

Table 6. Chinese OFDI and export sophistication of host countries, GMM estimation.

In the last two columns, the sample countries were divided into two groups: BRI participating countries and BRI non-participating countries. A 100% increase in China’s OFDI significantly improves export sophistication by 2.8%, while no significant effect of China’s OFDI is found in countries not participating in BRI. This supports Hypothesis 1b. These results align not only with the higher effect of China’s OFDI in BRI countries presented in column 4 of Table but are also entirely comparable to the higher effect of China’s OFDI (2.81%) found in middle-income BRI countries using the threshold model (see panel 5b in Table ). It seems that in Table , the estimated coefficients and their standard errors are biased downwards but are qualitatively similar to the GMM results presented in Table . Thus, the endogeneity of OFDI in our model does not change our main conclusions.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

Using a comprehensive dataset covering the period from 2010 to 2015, we investigate the effect of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI) on the export sophistication of host countries participating the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). We find that China’s OFDI contributes significantly to an increase in the export sophistication of host countries. The positive effect of China’s OFDI is much larger and more significant for BRI countries than for countries not participating BRI. Our main conclusions do not change much after accounting for potential endogeneity of OFDI.

We analyze the mechanism behind the promotion of China’s OFDI by taking into account the ‘China is special’ issue, which addresses the disparity between China’s exceptionally high export sophistication and its economic development level (Jarreau and Poncet Citation2012; Xu Citation2010). The potential replication of China’s successful model within the framework of the BRI hinges on the absorption of knowledge spillovers from China’s foreign investments. With the mediating effect of host countries’ productivity, the indirect technology spillover effects of China’s OFDI through the productivity channel account for 39% of its total effects on export sophistication.

We also identified significant threshold effects between China’s OFDI and the export sophistication of host countries. Specifically, the positive impact of China’s OFDI on export sophistication is significant when the GDP per capita of host countries is below the first threshold (approximately US$1,141) or between. After accounting for the threshold effect of China’s OFDI, we find much fewer significant differences in the effects of China’s OFDI between BRI and non-BRI host countries (non-BRI refers to countries not participating in BRI). Only for those middle income countries between the first and second thresholds (approximately US$1,141–US$7,115), China’s OFDI continues to have a significantly higher effect on the export sophistication in the BRI countries than in the countries not participating in BRI. This result confirms that the positive effect of China’s OFDI on export sophistication mainly reflects differences in economic, institutional, and cultural characteristics of BRI countries and countries not participating in BRI, rather than a pure policy effect.

Chinese partnerships with BRI countries can improve the level of export sophistication because most BRI countries are developing countries like China. China’s OFDI can also increase the export sophistication of countries not participating BRI, especially low and middle-income countries. This driving effect is not limited to the boundaries of the BRI but extends to all low and middle-income countries, which benefit more from the associated spillovers than high-income countries. Thus, we conclude that the positive impact of China’s OFDI extends beyond the BRI and benefits all low and middle-income countries.

The BRI presents a unique opportunity to enhance economic cooperation between developing and developed countries. BRI has the potential to offer more significant benefits to developing countries, creating opportunities for firms in partner countries to replicate the ‘China is special’ model and boost their value-added (Gurbuz Citation2024). As the driving force behind BRI, China can enhance the competitiveness and productivity of firms in partner countries through foreign investment and processing trade, further integrating them into the global production network. To achieve this, more facilities and organizations need to be established to facilitate international policy coordination in the new paradigm of division of labor, specialization, technology, and knowledge diffusion across countries. Further cooperation based on BRI is needed to improve trade and investment facilitation, policy coordination, infrastructure development and connectivity, financial coordination and integration, and people-to-people ties and connectivity among countries (Woodworth and Joniak-Lüthi Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to an anonymous reviewer and the editor for providing thorough comments and suggestions, contributing significantly to the enhancement of the paper. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge sole responsibility for any remaining shortcomings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Of course, COVID-19 has significantly impacted international trade flows from 2020 onwards.

2 It is well-known that the characteristics of the economic environment, such as infrastructure, local labor market conditions, reliability of communication systems, and the overall macroeconomic and trade policy climate, exert an important influence on the effect of FDI. However, to date, little is known about the comparative impact of these determinants. In this paper, we control for these variables and investigate their effects on export sophistication.

3 In our analysis so far, we established that the productivity of host countries plays a dual role as both the moderator and mediator in the enhancement of sophistication through China’s OFDI. Therefore, in this section, we naturally use the productivity as the threshold variable for our sensitivity test.

References

- Amiti, M., and C. Freund. 2010. “An Anatomy of China’s Export Growth.” In China’s Growing Role in World Trade, edited by Robert Feenstra and Shang-Jin Wei, 35–56. University of Chicago Press.

- Anwar, S., and S. Sun. 2018. “Foreign Direct Investment and Export Quality Upgrading in China’s Manufacturing Sector.” International Review of Economics & Finance 54 (C): 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2017.09.009

- Baldwin, R., and J. Lopez-Gonzalez. 2015. “Supply-Chain Trade: A Portrait of Global Patterns and Several Testable Hypotheses.” The World Economy 38 (11): 1682–1721. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12189

- Barrios, S., H. Görg, and E. Strobl. 2005. “Foreign Direct Investment, Competition and Industrial Development in the Host Country.” European Economic Review 49 (7): 1761–1784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.05.005

- Fan, Z., H. Li, and L. Pan. 2019. “FDI and International Knowledge Diffusion: An Examination of the Evolution of Comparative Advantage.” Sustainability 11 (3): 1–17.

- Fung, K. C., N. Aminian, X. M. Fu, and C. Y. Tung. 2018. “Digital Silk Road, Silicon Valley and Connectivity.” Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 16 (3): 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2018.1491679

- Golo, Yao Nukunu. 2023. “Foreign Direct Investment, Human Capital and Export Diversification in Africa: A Panel Smooth Transition Regression (PSTR) Model Analysis.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2023.2265496.

- Gurbuz, Eren Can. 2024. “Export Opportunities for Turkey in China Under the Belt and Road Initiative: Application of a Decision Support Model Approach.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2024.2310685.

- Harding, T., and B. Javorcik. 2011. FDI and Export Upgrading, University of Oxford Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series (No. 526).

- Hausmann, R., J. Hwang, and D. Rodrik. 2007. “What You Export Matters.” Journal of Economic Growth 12 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9009-4

- Huang, Y. 2016. “Understanding China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Motivation, Framework and Assessment.” China Economic Review 40: 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.07.007

- Jarreau, J., and S. Poncet. 2012. “Export Sophistication and Economic Growth: Evidence from China.” Journal of Development Economics 97 (2): 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.04.001

- Kang, L., F. Peng, and S. Anwar. 2023. “Cultural Heterogeneity, Acquisition Experience and the Performance of Chinese Cross-Border Acquisitions.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 28 (2): 738–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2021.1950112

- Kang, L., F. Peng, Y. Zhu, and A. Pan. 2018. “Harmony in Diversity: Can the One Belt One Road Initiative Promote China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment?” Sustainability 10 (9): 3264–3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093264

- Li, X., S. Anwar, and F. Peng. 2022. “Cross-border Acquisitions and the Performance of Chinese Publicly Listed Companies.” Journal of Business Research 141 (C): 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.053

- Li, C., and S. Tanna. 2018. “FDI Spillover Effects in China’s Manufacturing Sector: New Evidence from Forward and Backward Linkages.” In Advances in Panel Data Analysis in Applied Economic Research, edited by N. Tsounis and A. Vlachvei, 203–222. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Liu, H. Y., Y. K. Tang, X. L. Chen, and J. Poznanska. 2017. “The Determinants of Chinese Outward FDI in Countries Along “One Belt One Road”.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53 (6): 1374–1387. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1295843

- Lu, Y., Z. Tao, and L. Zhu. 2017. “Identifying FDI Spillovers.” Journal of International Economics 107: 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.01.006

- Luong, H., F. Moshirian, L. Nguyen, X. Tian, and B. Zhang. 2017. “How do Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Firm Innovation?” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52 (4): 1449–1490. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000497

- Mallick, J., and A. Q. Zhang. 2022. “Global Value Chains (GVCs) Participation Patterns and Impacts on Productivity Growth in the Asian Economies.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 27 (3): 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2022.2080428

- Ministry of Commerce. 2022. 2021 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Beijing: China Commerce and Trade Press.

- Panibratov, A., A. Kalinin, Y. G. Zhang, L. Ermolaeva, V. Korovkin, K. Nefedov, and L. Selivanovskikh. 2022. “The Belt and Road Initiative: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 63 (1): 82–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1857288

- Peng, F., L. Kang, T. Liu, J. Cheng, and L. Ren. 2020. “Trade Agreements and Global Value Chains: New Evidence from China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Sustainability 12 (4): 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041353

- Rodrik, D. 2006. “What is so Special About China’s Exports?” China and the World Economy 14 (5): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-124X.2006.00038.x

- Sun, Y., S. Zhang, and K. Zhang. 2024. “The Impact of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment on its Export Similarity with Belt and Road Countries.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 33 (1): 76–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2022.2159057.

- Swaine, M. D. 2015. “Chinese Views and Commentary on the “One Belt, One Road” Initiative.” China Leadership Monitor 47: 3–27.

- UN. 2018. Comtrade Database. United Nation Comtrade Database, International Trade Data. https://comtrade.un.org/.

- Wang, Z., and S. J. Wei. 2007. “What Accounts for the Rising Sophistication of China’s Exports?” National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Working Paper 377.

- Woodworth, M. D., and A. Joniak-Lüthi. 2020. “Exploring China’s Borderlands in an Era of BRIInduced Change.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1727758

- World Bank. 2018a. World Development Indicators. World Bank. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

- World Bank. 2018b. Worldwide Governance Indicators. World Bank. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/worldwide-governance-indicatorscators.

- Xiao, S., and B. I. Park. 2017. “Bring Institutions Into FDI Spillover Research: Exploring the Impact of Ownership Restructuring and Institutional Development in Emerging Economies.” International Business Review 27: 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.08.004

- Xu, B. 2010. “The Sophistication of Exports: Is China Special?” China Economic Review 21 (3): 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2010.04.005

- Xu, B., and J. Y. Lu. 2009. “Foreign Direct Investment, Processing Trade, and the Sophistication of China’s Exports.” China Economic Review 20 (3): 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2009.01.004

- Zhang, Y., Y. Li, and H. Li. 2014. “FDI Spillovers Over Time in an Emerging Market: The Roles of Entry Tenure and Barriers to Imitation.” Academy of Management Journal 57 (3): 698–722. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0351