Abstract

Background: Mental health services aim to provide holistic care, but the intimacy needs of clients are neglected. Currently there is limited understanding of the challenges mental health professionals (MHPs) face when considering supporting the relationship needs of people with psychosis.

Aim: This study investigated the views of community-based MHPs from a range of disciplines regarding the barriers and facilitators to supporting clients with their romantic relationship needs.

Method: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 professionals and analysed from a realist perspective using thematic analysis.

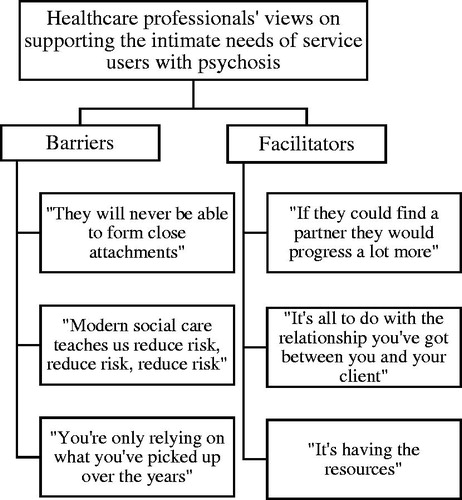

Results: Barriers identified were: (1) “They will never be able to form close attachments.” (2) “Modern social care teaches us reduce risk, reduce risk, reduce risk.” (3) “You’re only relying on what you’ve picked up over the years”. Facilitators were: (1) “If they could find a partner they would progress a lot more”. (2) “It’s all to do with the relationship you’ve got between you and your client”. (3) “It’s having the resources”.

Conclusions: Results highlight areas for service improvement and will help inform the development of future interventions.

Introduction

The onset of mental health difficulties is often followed by the breakdown of relationships, including romantic relationships (Baker & Procter, Citation2015), and people with psychosis experience significantly higher levels of loneliness compared to the general population (Chrostek, Grygiel, Anczewska, Wciórka, & Świtaj, Citation2016). People with psychosis may struggle to form romantic relationships for a number of reasons. First, the symptoms of psychosis can lead to withdrawal, making it difficult to approach and engage with new people. Second, individuals may experience discrimination due to their mental health, leading to internalised stigma and low self-esteem (de Jager, Cirakoglu, Nugter, & van Os, Citation2017). Finally, the prevalence of sexual abuse within this population is high (Read, Os, Morrison & Ross, Citation2005), which can negatively affect survivors’ ability to trust others and enjoy sexual contact (de Jager et al., Citation2017).

The Care Act 2014 states that service users should be actively involved in the development of their care plans to ensure recovery goals are meaningful to the individual. This personal approach to recovery values any activities or experiences that enhance an individual’s quality of life (Barnes, Boland, Linhart, & Wilson, Citation2017). For people with serious mental illness, low satisfaction with sexual relationships has been linked to lower overall quality of life (Östman, Citation2014). Additionally, qualitative research suggests that intimate relationships are perceived as normalising and related to recovery by people with psychosis (Boucher, Groleau, & Whitley, Citation2016; Redmond, Larkin, & Harrop, Citation2010). However, this is an area that is habitually neglected by mental health professionals (MHPs), despite the fact that people with psychosis face numerous obstacles to forming and maintaining romantic relationships (de Jager & McCann, Citation2017) and are often highly dissatisfied with their sex lives (Laxhman, Greenberg, & Priebe, Citation2017).

De Jager and McCann (Citation2017) called for further research regarding the intimacy needs of people with psychosis, with the view of developing intervention strategies. However, for interventions to be successful they must be feasible in practice, meaning they must be designed to overcome any barriers within the environment in which they will be delivered (Craig et al., Citation2008). Thus it is crucial to understand the views of professionals working within mental health services. Current information about the barriers – as perceived by staff – to supporting people who experience psychosis with their sexual and relationship needs can only be drawn from a few studies. A systematic review which sampled registered mental health nurses (RMNs) synthesised the results of just seven studies, six of which were from Australia and used the same cohort of RMNs from an inpatient setting (Hendry, Snowden, & Brown, Citation2018). Based on this limited evidence, barriers to providing support in this area were: the perceived inappropriateness of discussions about sex and intimacy; the displacement of responsibility to raise issues in this area on service users; the desire to avoid embarrassment; and the predominant perception of service users as “asexual” (Hendry et al., Citation2018, p. 1021). The review also highlighted RMNs’ concerns regarding how professional support or advice in this area would be perceived by colleagues and service users. Finally, a lack of education on the area was also seen as a problem (Hendry et al., Citation2018). A focus group study found poor access to sexual health services, condoms, and pregnancy tests was an issue (Hughes, Edmondson, Onyekwe, Quinn, & Nolan, Citation2018). Participants in this study felt discussions around sexual health would be facilitated by changes at an organisational level such as staff training, the promotion of sexual health testing, and use of proformas to assess relationships, sexual needs and dysfunction. However, the sample was comprised predominantly of RMNs and psychiatrists, which may have lead the results to be medically focussed i.e. concerned with sexually transmitted infections, side effects from medication, pregnancy (Hughes et al., Citation2018).

The present study aimed to extend previous research by including a range of community MHPs to examine the barriers – as well as facilitators – to supporting people who experience psychosis specifically with their psycho-social romantic relationship needs. Given the nature of the topic area and the research question, a qualitative methodology was chosen. Semi-structured interviews were used to permit flexibility, limit researcher bias and allow for the collection of rich and detailed data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). It is hoped that findings will help inform future romantic relationship interventions for people who experience psychosis.

Materials and methods

Participants

MHPs with at least six months of experience working in community mental health services with people who experience psychosis were recruited. Participants were recruited from two NHS trusts in north-west England. Recruitment materials were disseminated via email to clinicians working in Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and Early Intervention Services (EIS). Where invited, the first author (RW) also attended team meetings to give information about the study. Participants were also recruited through The University of Manchester, where recruitment information was circulated via email and displayed on posters. This study was open to professionals from a range of disciplines including: RMNs, support workers, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists.

Procedure

This study was given ethical approval by the HRA (IRAS ID 219081) and University Research Ethics Committee 4 at the University of Manchester (ref: 2017-0878-2539). MHPs were asked to self-refer by contacting RW. Those who did were contacted via email and a meeting was arranged where individuals gave voluntary consent to participate. All interviews were conducted in person by RW. A topic guide was developed according to guidance on qualitative interviewing (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Keats, Citation2000; Wilkinson, Joffe, & Yardley, Citation2004) and in collaboration with the other authors. The topic guide was reviewed after the first two interviews and halfway through data collection to improve the clarity of questions and help explore salient issues raised in previous interviews more directly. Interviews were recorded digitally, transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Analysis

Data were managed using NVivo 11 and analysed using thematic analysis (TA). TA was chosen as it well suited to identifying patterns across a data set and produces results which are easily accessible to audiences without a background in research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). Data were analysed from a realist perspective, meaning the researcher considered that data generated during interviews directly reflected participants’ thoughts on this topic and could be analysed to understand their true views and experience. Codes and themes were identified at a semantic level, meaning the researcher did not attempt to identify the underlying reasons for the opinions held by participants if they were not directly expressed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). Analysing the data in this way was considered to be most conducive to producing results that would be cogent to policy makers.

The overarching themes “barriers” and “facilitators” were specified prior to analysis and codes within these overarching themes were developed inductively. No new codes were identified within the last interviews, suggesting data saturation was reached (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). Similar codes were grouped together to create provisional themes which were explained and defended during peer debriefing with another member of the research team (Creswell & Miller, Citation2000). Finally, negative case analysis was conducted by searching for any data which contradicted the codes identified. This ensured a comprehensive final analysis (Henwood & Pidgeon, Citation1992).

Results

In total 20 participants (12 female, eight male) were recruited in an opportunity sample. Eleven were recruited from EIS, four from CMHTs, and five through the University of Manchester. Of these five, two had experience working within the NHS and three had worked in third sector organisations. Due to the heterogeneity of the sample, demographic data is provided in summary to ensure participant anonymity. MHPs from all disciplines, including social workers, occupational therapists, support workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and RMNs were included in the final sample. With regards to the length of time participants had worked with people who experience psychosis: seven participants had between one and five years of experience, six participants had between five and 10 of years experience and seven participants had over 10 years of experience. Interviews lasted 36 minutes on average.

Some general features of the data are discussed initially, to provide a background in which the analysis can be grounded. First, participants recognised that the romantic relationship needs of people with psychosis are neglected by mental health services: “Mental health services probably aren’t very good at doing that work at the moment” (P12). Second, participants perceived providing support in this area would be difficult: “it’s quite a clinically challenging area I think” (P10), due in part to the perception that conversations about intimate relationships are potentially “uncomfortable” (P6). Finally, participants perceived the support needs of individual service users would vary on a case by case basis: “with stuff like relationships because there is no one size fits all” (P2).

Six themes were developed from the data. The overarching themes “barriers” and “facilitators” included three themes each, as shown in .

Barriers

“They will never be able to form close attachments”

Participants perceived romantic relationships to be an important part of human life, regardless of diagnosis: “For most people relationships are a huge part of our lives, so why should somebody, because of their particular experiences, be excluded from that?” (P8). However, for people with psychosis, healthy romantic relationships were perceived as being difficult to form and maintain. Generally participants perceived that people with psychosis lacked skills in this area, making it uncommon for them to have wide social networks: “There are other people who also have the diagnosis schizophrenia who build really healthy relationships […] it’s less common but there are people that are able to do that.” (P3). Where participants referred to service users who did have a romantic partner, these relationships were frequently described as problematic, often due to the service user’s mental health.

People who I work with who are in relationships…those relationships are quite difficult for them and do cause them a lot of distress, sort of either on-off relationships or partners not being able to cope with the symptoms that service users are experiencing. (P17)

For those without partners, participants perceived that forming a relationship would be challenging for a number of reasons. People with psychosis were perceived as isolated, with limited opportunities to meet others and low self-esteem. Additionally, professionals perceived that stigma – both actual and internalised – was a barrier to people with psychosis forming relationships:

He had very low confidence, very low self-esteem, the psychotic symptoms that he developed were very critical, which reinforced a lot of his core beliefs about himself: that he’s a failure, he’s worthless, he’s skinny, nobody would ever want him. (P11)

The idea that they’d like a relationship is there but the idea then of going out, even to the shops on their own, is often very hard for them. (P16)

Participants perceived that addressing these issues and helping a service user find and maintain a relationship would be time consuming, creating a further barrier to providing support: “I don’t know how feasibly you would have the time to do it.” (P17)

“Modern social care teaches us reduce risk, reduce risk, reduce risk”

Participants viewed people with psychosis as vulnerable and romantic relationships as risky. Specifically, professionals were concerned that romantic relationships could lead to exploitation or service users experiencing a decline in mental health, especially if they experienced rejection:

I think we’re probably more concerned about vulnerability issues – whether people are being exploited in any way – so they may get with a partner who may exploit them for money or other things. (P15)

You’d maybe worry about if you were encouraging them to seek out relationships, that you’re maybe putting them at risk of being rejected, which might make them feel worse. (P8)

Participants perceived that reducing risk and ensuring safety was a priority within their role. Interestingly, despite viewing service users as autonomous, participants believed they would be held responsible if service users’ romantic relationships resulted in negative consequences, especially if they had supported them within that relationship:

You prioritise. You get a case load [and] you’ll immediately go through it and you prioritise the risk. And the risk of not having a relationship is well down […] we are driven by risk in this job (P16)

If anything happened with that individual they’re going to be looking at why has that happened? Who’s fault was it? If you’re the one that’s supported them, which has caused that situation to happen, your head will be right on that chopping block. (P3)

Despite this dominant narrative, there were instances in which participants perceived they may be unnecessarily anxious regarding the risk of relationships. However, these views were expressed by a minority of participants:

She’d [former service user’s partner] had an affair […] and I thought he [former service user] was gonna flip, I really did […] I went: “Oh God he’ll end up back under us”, cos stressful situations used to make him bad. But he handled it really well. (P19)

“You’re just relying on what you’ve picked up over the years”

Participants reported a lack of policy and training around how to support service users with romantic relationships. When recalling times they had supported a service user with a relationship issue, participants perceived that they had done so without guidance: “It wasn’t like a policy ‘if somebody’s going through this, then we have to do this’ […] it didn’t come from above basically, it came from the lower staff” (P1). As a result participants perceived that the boundaries of their role as a professional were unclear: “Appropriate boundaries and how far to take that kind of support and treatment, because I think that’s something that’s very difficult to decipher” (P4).

Facilitators

“If they could find a partner they would progress a lot more”

Despite perceiving that healthy romantic relationships would be difficult for people with psychosis to form and maintain, participants believed if service users were able to achieve such relationships it would lead to positive outcomes:

Having romantic partners, what comes with that is a lot of protective factors; the understanding, the support, the sounding out their worries and normalisation. (P20)

I was talking about self-esteem and worrying about it knocking their self-esteem. At the same time I really think it would build it as well and it would give them a reason to take care of themselves. (P3)

Similarly, participants perceived unmet romantic relationship needs could contribute to the maintenance of service users’ presenting difficulties. The idea that deficits in intimacy obstruct recovery motivated professionals to support people with this aspect of their lives.

I’ve had similar conversations in both teams about “such a body, all they need is a partner or something” and you think: “yeah, they’d be great, that’s the thing that they’re lacking”. (P15)

“It’s all to do with the relationship you’ve got between you and your client”

Participants perceived that people with psychosis did not always engage with mental health services and a good working relationship was a prerequisite of supporting a service user with their romantic relationships; especially as this area of service users’ lives was understood to be “personal” (P4).

I think sometimes service users disengage from a care coordinator if they’re not able to talk openly and feel comfortable (P5).

We did have a good relationship so I did feel like we could explore some of those issues. (P7)

Professionals perceived that the pairing of their own age and gender with a service user’s could have an influence on the relationship they were able to build. Generally participants perceived that being a similar age and the same gender was most conducive to conversations about romantic relationships taking place. However, negative case analysis showed conversations about romantic relationships could also take place when professionals and service users were not demographically similar:

I don’t know, maybe it is just because I’m [a] similar age and they feel that maybe [it’s] less embarrassing to talk about with me than it is with somebody who’s like their mum. (P17)

It’s so individual I think, a lot of the time, to the person that’s using the service. Some people prefer to talk to the same person, so female to female. That guy didn’t, he preferred to talk male to female. (P11)

In addition to having a good working relationship, participants perceived providing support with romantic relationships would be further facilitated where the client was pro-active in seeking support. This appeared to be linked to worries around damaging the working relationship and limited resources leading to the prioritisation of other areas, namely risk: “If you had the resources and the time, yes, you would do more, but frequently you just don’t unless they say ‘this is what I want to do’ and they prioritise it” (P16).

“It’s having the resources”

When considering their capability in supporting people with psychosis, participants perceived that having experience within a role was beneficial and that confidence and ability developed with time: “It’s definitely not something I felt well equipped with when I started working” (P4). However, participants still perceived that it would be valuable to have guidance and training in this area. Whilst participants reported they would currently seek advice from colleagues, they believed more formal guidance would be helpful with regards to defining appropriate practice: “I think it could be guidance policy. What’s appropriate? What’s our clinical role in that? The expectation.” (P18). Generally, participants felt it would be useful to receive training around how to have conversations with service users about their intimacy or relationship needs, as well as the practical support that could be offered: “How do you broach the subject? How’d you work to resolve it” (P11). However, some were sceptical about the difference guidance and training could make: “Even if there was formal guidance I think it would still be an issue that staff would be wary of discussing that with patients” (P13).

Perhaps linked to the perception that supporting clients to achieve healthy romantic relationships would be time-consuming, participants often perceived others may be better placed than themselves to provide support in this area. Some felt the availability of staff such as peer support workers, recovery workers, and occupational therapists, who were perceived to have a more social role, could help facilitate the provision of support with romantic relationships: “I suppose they’d have a bit more time and a bit more informal time to be spending with individuals” (P14). Additionally, professionals perceived that external services could take responsibility for the provision of support in this area as they would have the additional benefit of being specialised: “You stick to what you’re good at and you can maybe give ‘em a bit of advice but really you’re better off signposting to somebody who deals in that all day” (P19).

Professionals perceived that service user groups may help reduce internalised stigma and build confidence in people with psychosis by providing the opportunity to meet others with similar experiences. However, participants were conflicted as they did not see service user groups as socially inclusive:

I suppose some of it would look at putting on events and doing things that would bring service users together, but then there’s the issue of if you’re doing that are you just almost ghettoising service users into meeting other service users? (P16)

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the views of community MHPs regarding the romantic relationship needs of service users who experience psychosis. Specifically, the study sought to identify the perceived barriers and possible solutions to providing support in this area of clients’ lives. Previous research by Hendry et al. (Citation2018) suggested MHPs did not recognise service users as sexual beings and perceived conversations about intimate relationships to be embarrassing and inappropriate. However, participants in this study acknowledged the importance of romantic relationships to service users with psychosis. Whilst they did consider that conversations in this area could be uncomfortable, they viewed work in this area as challenging, rather than inappropriate.

details how the key issues highlighted by this study may be addressed by services at an organisational, staff and service user level.

Table 1. Barriers and potential solutions to providing support with romantic relationship issues.

A novel finding of this study was concern over risk. This is understandable given recent high-profile investigations around cases such as the deaths of patients at Stafford Hospital due to poor care (National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England, Citation2013), and the NHS’s ambition to be “the safest healthcare system in the world” (NHS Improvement, Citation2017, p.4). However, paternalism is inconsistent with modern conceptualisations of recovery (Pilgrim, Citation2008). Good working relationships with service users may reduce professionals’ anxiety around risk due to increased relational security (i.e. awareness of a service user’s history and triggers, collaboration around care planning, ability to notice subtle changes in behaviour) (NHS, Citation2010). Participants perceived a good working relationship to be a precursor to conversations about romantic relationships. Therefore the idea of relational security may resonate and could increase confidence around positive risk taking.

Consistent with findings from Hendry et al. (Citation2018) and Hughes et al. (Citation2018), participants felt training would be beneficial. Staff training may encourage the provision of support in this area by rationalising anxiety about risk and providing information regarding the potential benefits of romantic relationships. At an organisational level, guidelines would improve clarity around the boundaries when providing support in this area and could help reduce anxiety regarding liability as professionals may feel protected by adhering to policy.

The issue of limited time could be overcome by increasing the provision of services. Additionally, given that services strive to be service user-led, participants felt it would also be helpful if clients explicitly stated they wanted support in this area. At a service user level, the provision of training may reduce pressure on staff time and help address the barriers, as discussed in the introduction and the theme “they will never be able to form close attachments”, faced by people who experience psychosis to forming and maintaining fulfilling intimate relationships. It is worth noting that within the theme “they will never be able to form close attachments” participants referred specifically to the distinctive characteristics of psychosis. For example, poor social functioning was often mentioned as a barrier. However, there was less consideration of the nature of psychosis specifically within the other themes developed. Therefore future research may seek to explore if the barriers and facilitators identified by MHPs in this study are applicable to other service user groups.

Finally, given the support each service user requires is likely to be different, it may be judicious to develop modular interventions which are comprised of multiple components that can be delivered as stand-alone sessions or combined, according to individual service user needs, in a flexible way to complement each other.

Limitations

MHPs self-selected to participate in this study, therefore it is likely that those who were more interested in the topic area and comfortable talking about intimate relationships will have chosen to take part (Robinson, Citation2014). This may mean that those with more conservative views are not represented. Additionally, due to the diverse sample, it was not possible to meaningfully investigate potential differences based on participant characteristics (e.g. profession) which conceivably exist.

Conclusion

The findings from this research highlight the complexities, as perceived by MHPs, of supporting people with psychosis with their romantic relationship needs. If professionals are to consistently address the romantic relationship needs of service users then change at multiple levels within mental health services is needed. Future research should aim to explore the type of support people with psychosis would like from services and move towards developing interventions which are acceptable to both service users and staff.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baker, A. E., & Procter, N. G. (2015). ‘You just lose the people you know’: Relationship loss and mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(2), 96–101. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.007

- Barnes, D., Boland, B., Linhart, K., & Wilson, K. (2017). Personalisation and social care assessment – the Care Act 2014. BJPsych Bulletin, 41(3), 176–180. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.053660

- Boucher, M. E., Groleau, D., & Whitley, R. (2016). Recovery and severe mental illness: The role of romantic relationships, intimacy, and sexuality. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(2), 180–182. doi:10.1037/prj0000193

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research, a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications.

- Chrostek, A., Grygiel, P., Anczewska, M., Wciórka, J., & Świtaj, P. (2016). The intensity and correlates of the feelings of loneliness in people with psychosis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 70, 190–199. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.07.015

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 337, a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- de Jager, J., Cirakoglu, B., Nugter, A., & van Os, J. (2017). Intimacy and its barriers: A qualitative exploration of intimacy and related struggles among people diagnosed with psychosis. Psychosis, 9(4), 301–309. doi:10.1080/17522439.2017.1330895

- de Jager, J., & McCann, E. (2017). Psychosis as a barrier to the expression of sexuality and intimacy: An environmental risk? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(2), 236–239. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbw172

- Hendry, A., Snowden, A., & Brown, M. (2018). When holistic care is not holistic enough: The role of sexual health in mental health settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5–6), 1015–1027. doi:10.1111/jocn.14085

- Henwood, K., & Pidgeon, N. (1992). Qualitative research and psychological theorizing. British Journal of Psychology, 83(1), 97–111. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02426.x

- Hughes, E., Edmondson, A. J., Onyekwe, I., Quinn, C., & Nolan, F. (2018). Identifying and addressing sexual health in serious mental illness: Views of mental health staff working in two National Health Service organizations in England. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 966–974. doi:10.1111/inm.12402

- Keats, D. (2000). Interviewing: A practical guide for students and professionals. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Laxhman, N., Greenberg, L., & Priebe, S. (2017). Satisfaction with sex life among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 190, 63–67. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.005

- National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England. (2013). A promise to learn – a commitment to act, Improving the Safety of Patients in England. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226703/Berwick_Report.pdf

- NHS. (2010). See Think Act. Your guide to relational security. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/320249/See_Think_Act_2010.pdf

- NHS Improvement. (2017). Our approach to patient safety, NHS Improvement’s focus 2017/2018. Retrieved from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/our-approach-to-patient-safety/

- Östman, M. (2014). Low satisfaction with sex life among people with severe mental illness living in a community. Psychiatry Research, 216(3), 340–345. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.009

- Pilgrim, D. (2008). Recovery'and current mental health policy. Chronic Illness, 4(4), 295–304. doi:10.1177/1742395308097863

- Read, J., Os, J. V., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330–350. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634

- Redmond, C., Larkin, M., & Harrop, C. (2010). The personal meaning of romantic relationships for young people with psychosis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(2), 151–170. doi:10.1177/1359104509341447

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. doi:10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Wilkinson, S., Joffe, H., & Yardley, L. (2004). Qualitative data collection: Interviews and focus groups. In D. Marks, & L. Yardley, (Eds.), Research methods for clinical and health psychology (pp. 39–55). London: Sage Publications.