Abstract

Background: Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) constitutes a key element of England’s national mental health strategy. Accessing IAPT usually requires patients to self-refer on the advice of their GP. Little is known about how GPs perceive and communicate IAPT services with patients from low-income communities, nor how the notion of self-referral is understood and responded to by such patients.

Aims: This paper examines how IAPT referrals are made by GPs and how these referrals are perceived and acted on by patients from low-income backgrounds

Method: Findings are drawn from in-depth interviews with low-income patients experiencing mental distress (n = 80); interviews with GPs (n = 10); secondary analysis of video-recorded GP-patient consultations for mental health (n = 26).

Results: GPs generally supported self-referral, perceiving it an important initial step towards patient recovery. Most patients however, perceived self-referral as an obstacle to accessing IAPT, and felt their mental health needs were being undermined. The way that IAPT was discussed and the pathway for referral appears to affect uptake of these services.

Conclusions: A number of factors deter low-income patients from self-referring for IAPT. Understanding these issues is necessary in enabling the development of more effective referral and support mechanisms within primary care.

Introduction

England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme began in 2008 with an aim to provide large-scale National Health Service (NHS) treatment for common mental health problems such as mild to moderate anxiety and depression. Whilst IAPT is widely promoted, little is known about the ways GPs communicate this treatment option to patients, or how referral into the system impacts on patient perception and use of the service. Here we examine the now widespread expectation amongst GPs and service providers for patients to self-refer for IAPT, and explore how this impacts on service use and wellbeing amongst people from low-income backgrounds. Understanding here is especially important given known links between poverty and mental health, and high levels of antidepressant prescribing in low-income communities (EXASOL, Citation2017). Despite the positive intentions of GPs and service providers, our findings suggest that self-referral can act as a barrier for low-income patients seeking psychological therapies.

Background

Between the creation of the NHS in 1948 and initiation of the IAPT programme in 2008, most patients required a GP referral to receive specialist psychological therapy. On-going concern that this may be influencing long waiting times and acting as an obstacle to service access (Clark et al., Citation2009) was underlined by a National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey that found that approximately 70% of people with mental health problems did not present to their GPs and therefore did not have access to psychological therapy (Brown, Boardman, Whittinger, & Ashworth, Citation2010).

In response, the two sites set up to trial the IAPT service were allowed to accept self-referrals to assess the effectiveness of this mechanism for engaging people who may not otherwise access therapy. In Newham (London), extensive use was made of self-referral, with one in five of those seen in IAPT referring themselves into the system. Despite initial concerns that self-referral would increase numbers of the ‘worried well’ accessing limited services (Brown et al., Citation2010), when compared to GP-referrals, self-referral patients were found to be at least as ill, to have had their problems for longer, and more closely matched the ethnic mix of the local population (Clark et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, self-referrers were found to be no less likely to recover than those referred by GPs. This led researchers to conclude that the necessity for GP-referral could indeed be acting as a deterrent for people seeking psychological support (Grant et al., Citation2012), and in turn, influenced the government decision to include self-referral in the subsequent national roll-out of IAPT (Department of Health, Citation2008).

Self-referral has additional advantages: it is well-suited to patients whose lifestyles make it difficult to access their GP during surgery hours; can help avoid stigma; and can act as an alternative entry point for support that may reduce potential for medicalisation. Brown et al. (Citation2010) argue it ‘may facilitate access to those who are particularly difficult to reach, and contributes to a more equitable NHS’ (ibid, p. 368). Research in other sectors has also found strong support for patient self-referral by professional bodies and healthcare policies, in part at least, because of its positive implications for GP workload (e.g. Holdsworth, Webster, & McFadyen, Citation2007).

Whilst self-referral was originally intended as a mechanism to broaden access to psychological therapies, there has been little examination of how this has played out over time or may impact population groups differently, nor how the notion of self-referral is received by GPs and low-income patients, and may subsequently impact on help-seeking for mental distress.

Methods

This paper reports on the DeStress project, a qualitative study undertaken in two urban sites in South West England. Both sites represented the least affluent quintile as determined by the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. The study examined: the impact of austerity and welfare reforms on mental health in low-income communities; how current mental health provision could be improved to better support low-income patients. Ethical approval was granted by the Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire NHS REC (ref: 16/EE/0322). Participants consented for their data to be used in the research.

Recruitment

Findings reported here are drawn from eighty in-depth interviews with fifty-seven people who had sought medical support for mental distress. All participants identified themselves as living in households where poverty-related challenges such as unemployment or being in insecure, low paid work were experienced. This self-identification took place prior to the interview when researchers and participants communicated (in person or via telephone) regarding the aims and sampling strategy of the study.

Interviews were also undertaken with GPs (n = 10) working in the study sites or nearby areas with high proportions of low-income patients. Potential participants were alerted to the study by community and health practitioners, social media and word-of-mouth and recruited through community groups and GP surgeries.

This primary data was supplemented by secondary data from the One in a Million (OM) database (Barnes, Citation2017; Jepson et al., Citation2017) using video-recorded GP-patient consultations for mental health where self-referral to IAPT was discussed (n = 26).

Data collection

A semi-structured topic guide was produced for patient interviews, informed by the literature, and in collaboration with the project Advisory Board (comprising low-income residents, third sector, and health professionals). This covered patient expectations around treatment and support; experiences of GP consultations and the main treatments on offer i.e. antidepressants and IAPT. Interviews lasted 30 min – 2 h. Participants engaged in the health system at the time of the study, and participants who wanted more time were interviewed on two occasions approximately four months apart (n = 23) to ensure their experiences were fully captured and could be followed over time. The remaining 34 participants chose to participate in one interview.

A semi-structured topic guide was produced for interviews with GPs, covering their experiences of supporting mental health amongst low-income patients, and their perceptions of current treatment options. Interviews lasted 30 min – 1 h. All interviews were audio recorded (with permission) and transcribed verbatim. Data from the OM dataset were sorted to identify consultations that included discussion of self-referral to IAPT. Of the fifty-two consultations in the dataset, 26 were included for analysis on self-referral.

Data analysis

Interview and video-recorded data were analysed by three team members using QSR International’s NVivo 11 Software, using inductive and deductive thematic coding to identify relevant data categories. Initial analysis took place independently with the three team members then meeting to discuss themes identified and check for consistency in coding and analysis. Themes included ‘treatment offered’ and ‘treatment outcomes’ (with sub-themes of ‘self-referral’, ‘talking therapies’ and ‘influences on patient decision-making’) and ‘GP perspectives on self-management’.

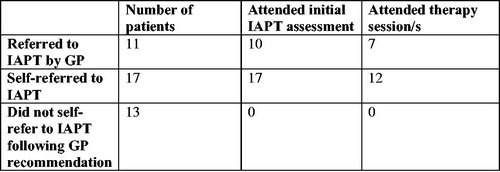

Forty-one of the fifty-seven participants interviewed had been given information about IAPT by their GP (see ). Eleven had been referred to talking therapy by their GP. Of these, ten had attended IAPT assessment, with seven then attending one or more therapy sessions. Seventeen participants had self-referred to IAPT, of whom twelve attended at least one IAPT session, and five only initial assessment. One of these participants self-referred without seeing their GP first. Thirteen participants who had been told about IAPT had chosen not to self-refer.

Moments when self-referral was discussed in video-consultation data were analysed using conversation analysis. Focus was placed on language used by the doctor to explain self-referral, and patient responses to this. Common features were noted across all cases, and cases where patients seemed resistant to self-referral were transcribed at length using Jefferson (Citation2004) conventions.

Results

GP practice

IAPT self-referral was discussed in 26 of the video-recorded consultations. Information on psychological therapy was usually imparted by the GP through a brief statement on the availability of IAPT, followed by presentation of a leaflet detailing the locally available IAPT service. Analysis revealed a clear tendency for GPs to present self-referral as relating to patient choice (e.g. “if you want, you can self-refer”) to follow-up on the information they were being given. GPs also placed clear emphasis on downplaying potential challenges that patients might face in self-referring, particularly when a patient had expressed some reluctance to do so. This was typified by comments such as ‘It’s just a phone call’, or “It’s only a local number.”

This tendency to stress the straightforward nature of self-referral was also apparent in the primary interviews undertaken with GPs, the following statements typifying this response,

I’ll give them the leaflet, yes – actually, I don’t even always give the leaflets because if people are online, I’ll say just Google it [IAPT] – it’s perfectly visible for everybody isn’t it (GP 8)

Most people, with a service like [IAPT provider], should be able to self-refer. You can self-refer to physiotherapy, so you should be able to refer to [IAPT] (GP 9)

Obstacles to self-referral

At the same time as GPs stressed the ease of self-referral, patient interviews revealed a strongly held perception that self-referral presented a real barrier to attending IAPT. During interviews, patients emphasised the difficulties they experienced engaging with others, especially when they were feeling low, and how the idea of engaging with people they did not know could exacerbate their distress,

I’ve got social anxiety, and the whole idea of something new scares the hell out of me. Taking that first step to actually do something that already scares me, just makes me ten times worse (Libby)

The doctor couldn’t refer me to them, my wife can’t refer me to them. I’ve got to phone them, make an appointment and then I’ve actually got to turn up […] if you’re having problems of stress and self-belief, and self-worth, you’re going to go ‘I’m not going to go, I’m too tired, I’m not going to do that’. (Justin)

Others, such as Chris, emphasised how their poor mental health detracted from their ability to take positive actions towards ‘recovery’ without additional support, whilst for Megan, the struggle to undertake basic daily tasks left her unable to contemplate the enormity of self-referral.

Self-referring is a very hard process for somebody with mental health issues. It doesn’t matter if it’s anxiety, depression, whether it’s anything else. To self-refer, it is difficult unless you have that extra push. And trying to do it on your own, you don’t want to say you are weak, you need help (Chris)

They gave me a self-referral thing to [IAPT provider] - if I can’t even pay my bills and I can’t even post a letter on time, then how am I going to do a self-referral? If you don’t pay your water, you’ve got no electric, no gas, how can you live? But you don’t think about that when you’re depressed, you’re like, if somebody else does it for you, you feel better. If somebody posts that letter for you, or if somebody pays that bill – I mean, I’ve got bills stacking up, letters that I need to answer, and it’s just not that easy. So they go, here, self-referral, and you’re like ‘no’ – that’s why I need counselling to get me out of this mess (Megan)

As demonstrated by these quotes, there was widespread feeling that people experiencing mental distress needed extra support to take the first step to help themselves. This was exacerbated when low-income patients felt they had to consistently ‘fight’ to access other services e.g. GP appointments, housing and welfare benefits. Under such circumstances, the self-referral process felt overwhelming, and was widely considered as another mechanism to alienate low-income patients from core services. As Clarice explained, the need for someone to ‘open a door for you’ during challenging times was felt to have the potential to make an important difference,

You just have to fight for absolutely everything, so unless you come across someone who opens a door for you - you can see one hundred really awful people but you can have that one person you see who gives you hope, and that lifts you up and it makes you want to fight and want to carry on (Clarice)

Others, such as Craig, emphasised how he felt ‘guilty’ about using the resource, so would prefer the referral came through a more ‘legitimate’ source of authority, a feeling reiterated by patients who felt that the GP would have done the referral for them if they were taking their concerns seriously,

Nowadays you’ve got to refer yourself to these things, and you don’t when you feel guilty about using up resources when cuts are being made, and you don’t like using the telephone to phone up […] If you pick up the phone and make an appointment for yourself, you are more likely to turn up to it. I can see the logic behind it. But you are dealing with people who have mental health issues and they don’t work like that (Craig)

It was also common for participants to describe how difficult they found it talking about mental health with their GP, explaining how their economic and social status meant they felt they would be viewed as ‘undeserving’ and as ‘time wasters’,

“I see people in here who are ready to jump off the bridge. Just go and pull yourself together.” That’s [what] a healthcare professional at our surgery said… I ain’t been back (Tim)

I think they’re looking at you as if you’re like a hypochondriac. That plays on your mind, should I go there or shouldn’t I, oh I’m alright […] I just don’t like to waste people’s time (Fred)

Participants explained how they had built up courage to both book and then attend the GP consultation, only to feel ‘fobbed off’ when the GP gave them a leaflet about psychological therapies. For patients such as Dennis and Susie, the handing over of the IAPT leaflet felt like a form of symbolic dismissal that undermined their legitimacy and deterred them from returning to their GP.

It took me a lot to go to my doctor. And when I got there, on the first attempt, they gave me that leaflet. And I was just like, ‘I didn’t come here for a leaflet. I came here for some help […] He just sent me away. It was like ‘There you go, there’s your leaflet, bye’ (Dennis)

It was a case of, ‘here’s a phone number, off you go.’ […] After she [GP] left me in a sodden mess, she said ‘Well I think you need to go and have some talking therapy’, slapped a phone number and a bit of paper in front of me, and that was it – it was ‘next’ (Susie)

This feeling of dismissal and de-legitimisation was exacerbated when patients felt their GPs did not know what the IAPT service actually entailed, and when GPs did not appear to strongly endorse treatments they were recommending (Ford, Thomas, Byng, & McCabe, Citation2019). However, few interviewed felt able to articulate these concerns to their GP, meaning they left the consultation feeling dejected and knowing they would not follow-up on the IAPT recommendation.

GP reasons for encouraging self-referral

GPs were asked to discuss their experiences of the IAPT self-referral process as it related to low-income patients. There was broad recognition of the difficulties patients felt initiating IAPT referral when they were experiencing depression and anxiety,

It has to be up to the patient to make that change, but when they are feeling so low, it is hard for them to do that. They need good support around them to encourage them to even get out of bed in the morning, and stick to that routine, and even the thought of getting to the appointment is overwhelming (GP 2)

However, all felt the self-referral process was helpful for patients and for the IAPT service itself, since it reduced non-attendance, and helped conserve limited resources for those who felt ready to make the necessary changes to improve their mental wellbeing. The following statements were typical of the GPs interviewed for the study,

If you refer someone in the consultation you can feel they are with you on it and they want to go along with it. But actually when they go home they really can’t be bothered to contact the place to make a referral, maybe they are not going to turn up […] in terms of services that are available and [have] squeezed provision, maybe it’s better for them to self-refer because it allows people who can get it together to make that phone call or go on the internet and fill the form out, it allows them to take that space (GP 6)

Self-referral is good because people have to take the initiative […]. The whole part is to feel yourself that you’ve got a problem and you want some help, because if you don’t have that, it’s not going to [work]. I could do a referral, but if somebody can’t be bothered, it’s a waste of my time (GP 8)

That these GPs put failure to attend IAPT down to patient inertia implies the very real potential for disconnect between what are sometimes judgmental perceptions and actions (exacerbated under pressure), and the fears, anxieties and low self-esteem that some patients experience. GPs also felt strongly that self-referral constituted a first step towards recovery, with the notion that patients needed to ‘help themselves’ and ‘take ownership’ of the process if they wanted to get better coming through clearly in interviews,

When we used to refer them they just used to DNA [not attend] all the time […] And self-referral’s part of you getting better. If they say, ‘Oh, I don’t like picking up the phone’, you just encourage them to try and help themselves (GP 4)

GPs also stressed the emotional work required by patients seeking ‘recovery’ through IAPT, and the ways this could influence patient expectations and clinical prescribing practice. One GP for example, explained that she felt low-income patients preferred the ‘easy option’ of antidepressants over talking therapies, and as a result, was reluctant to refer patients who she did not believe would attend IAPT.

Several GPs also stressed the time and resource limitations they faced, emphasising the necessity to hand responsibility to the patient at a time when they were themselves being asked to cover additional duties without sufficient administrative and logistical support,

It’s just as easy and quick for me to give them the IAPT leaflet and actually that then gives them ownership of it. I could refer them but I try to get people to phone themselves because then that gives them more control over it too (GP 10)

I think it’s [self-referral] definitely beneficial. Then when patients come back, I’ll say, ‘Have you gotten in touch with [local IAPT service]?’ ‘Oh no, I haven’t done that’ – it’s just passing responsibility on to patients that they need to make a change; that I can’t do everything; that they actually have to (GP 7)

GPs as referrers

Patient and GP interviews identified instances where GPs had made a referral to IAPT on behalf of their patient. GPs who had done this explained this was not something they did routinely, but that they may take this approach if they felt strongly that this would influence the likelihood of the patient attending therapy. GPs also stated the importance of time, reflecting that they would be most likely to do this for appointments at the end of the day. Relaying one such consultation a GP explained how she was responding to the logistical challenges facing a patient whom she knew well,

I realised that given she’s got no money she probably couldn’t [phone] – she doesn’t have access to internet […] she said “I’ll have to wait til I get my money through and then I’ll be able to ring them.” So I just did the online form for her in the consultation because she was my last patient. I had a bit of time (GP 5)

Patients who had had a GP referral to IAPT explained how they felt validated, and that this impacted positively on their wellbeing. Cara for example, explained how ‘having it [IAPT-referral] done through the GP actually made me think that I wasn’t neurotic’ and that ‘not being made to feel like you’re a pain’ had been especially reassuring.

Experiences of IAPT

A range of frustrations were reported amongst participants who did ultimately attend IAPT. This included waiting times and the delay between assessment and referral to Step 3 support; the ‘one-size fits all’ approach with its rigid protocols and focus on CBT which people felt failed to address the underlying causes of their problems; and difficulties patients experienced connecting emotionally with a therapist. Whilst such findings cohere with other research (e.g, Marshall et al., Citation2015), it is possible that those with more negative experiences were more likely to have come forward to feed this back than those finding IAPT helpful.

Discussion

Self-referral was initiated to help achieve equity in access to England’s IAPT programme. However, our findings demonstrate that for low-income patients, self-referral can act as a deterrent to accessing psychological therapies. Indeed, over 40% of those who received a recommendation for self-referral did not follow this through. Whilst issues around self-referral may also apply to more affluent patient groups, it is likely that they are exacerbated when patients face barriers accessing basic resources e.g. phone, internet, and when people feel that their low income and societal status reduces their self-worth and sense of entitlement. Indeed, far from acting to support patients, the very notion of self-referral can, in some instances, exacerbate disconnect between GP practice and patient experience. In particular, there appears often to be disconnect between GPs’ perceptions of patients’ ability to take ‘responsibility’ for their recovery, and how low and disempowered patients actually feel.

Such circumstances arise from a complex and multifaceted combination of economic, social and moral challenges facing GPs and patients. What is clear however is that language and communication around help-seeking for mental health matters. What may seem like inconsequential wording and action in the consultation and the handing over of an information leaflet can have clear repercussions for the ways that patients feel, and in turn, their likelihood of following-up on the doctor’s advice. When patients have had to muster the courage and energy to attend a clinical consultation only to then feel their concerns are not sufficiently deserving of a GP executing a referral, this is undermining, and the chances of them self-referring to IAPT are minimal.

There is a need therefore, to identify more supportive, patient-centred approaches that are mindful of fears and anxieties that patients might have about speaking openly within consultations, and that recognise that judgmental perceptions and assumptions can exist on both sides of the GP-patient relationship. Importantly, there is a need for GPs to remain vigilant to patient cues that indicate the likelihood of possible barriers to treatment recommendations being taken up, and for GPs to sensitively accept these and find ways of letting patients expand on them.

The preceding discussion raises complex questions regarding where responsibility for IAPT referral lies. Whilst GP referrals risk being overly paternalistic and time consuming, deferring all responsibility to low-income patients can leave them feeling undermined, resulting in low levels of treatment expectation and take-up. Working out which options make sense to the patient based on a shared bio-psycho-social model, giving a patient clear information about what each of these options involves, and providing time for people to think and discuss their options is likely to support more effective decision-making and treatment take-up. At the same time, and whilst in no way advocating GPs assume all responsibility for IAPT referral, it is important that GPs feel able to make these referrals when they and the patient feel it is in the patient’s best interest to do so. Such actions may also provide a mechanism for GPs to better understand the IAPT service on offer, and to create joined-up three-way conversation between themselves, the IAPT service and the patient.

At present, patient experiences of the IAPT programme are influenced, at least to some extent, by assumptions that posit that patients who are genuinely in need will self-refer. This exacerbates pressures on potentially vulnerable patients and continues to act as a barrier for low-income patients – and potentially other groups, seeking psychological support therapies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data access statement

The anonymised data generated from this study are available from the UK Data Service, subject to registration at 10.5255/UKDA-SN-853788.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnes, R. K. (2017). One in a Million: A study of primary care consultations. doi:10.5523/bris.l3sq4s0w66ln1x20sye7s47wv

- Brown, J. S. L., Boardman, J., Whittinger, N., & Ashworth, M. (2010). Can a self-referral system help improve access to psychological treatments? British Journal of General Practice, 60(574), 365–371. doi:10.3399/bjgp10X501877

- Clark, D. M., Layard, R., Smithies, R., Richards, D. A., Suckling, R., & Wright, B. (2009). Improving access to psychological therapy: Initial evaluation of two UK demonstration sites. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 910–920. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.010

- Department of Health. (2008). Improving access to psychological therapies: Implementation plan: National Guidelines for Regional Delivery. Retrieved November 26, 2018, from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130124042312/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_083168.pdf

- EXASOL. (2017). EXASOL Analyzes: Research shows that over 64m prescription of antidepressants are dispensed per year in England. Retrieved December5, 2017, from https://www.exasol.com/en/company/newsroom/news-and-press/2017-04-13-over-64-million-prescriptions-of-antidepressants-dispensed-per-year-in-england/

- Ford, J., Thomas. F., Byng, R., & McCabe, R. (2019). How do patients respond to GP recommendations for mental health treatment? British Journal of General Practice Open. doi:10.3399/bjgopen19101670

- Grant, K., McMeekin, E., Jamieson, R., Fairful, A., Miller, C., & White, J. (2012). Attrition rates in a low-intensity service: A comparison of CBT and PCT and the impact of deprivation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 40(2), 245–249. doi:10.1017/S1352465811000476

- Holdsworth, L. K., Webster, V. S., & McFadyen, A. K. (2007). What are the costs to NHS Scotland of self-referral to physiotherapy? Results of a national trial. Physiotherapy, 93(1), 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2006.05.005

- Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H.Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–23). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Jepson, M., Salisbury, C., Ridd, M. J., Metcalfe, C., Garside, L., & Barnes, R. K. (2017). The ‘One in a Million’ study: Creating a database of UK primary care consultations. British Journal of General Practice, 67(658), e345–e351. doi:10.3399/bjgp17X690521

- Marshall, D., Quinn, C., Child, S., Shenton, D., Pooler, J., Forber, S., & Byng, R. (2015). What IAPT services can learn from those who do not attend. Journal of Mental Health, 25, 410–415. doi:10.3109/09638237.2015.1101057