Background

Suicide is a major public health issue (WHO, Citation2014) with more than 800,000 people taking their own lives worldwide per year. This loss of life has devastating effects on families and friends and the person’s wider network (Pitman, Osborn, King, & Erlangsen, Citation2014). Patients in contact with mental health services and those who present to hospital following self-harm are identified by national suicide prevention strategies as key target groups for reducing suicide rates (WHO, Citation2018). Despite decades of research into self-harm and suicide prevention, there are significant gaps between research, policy, and clinical practice. In this editorial, we discuss how adopting a patient safety paradigm can provide additional insights into suicidal behaviour in mental health services and generate new opportunities for suicide prevention.

The patient safety paradigm

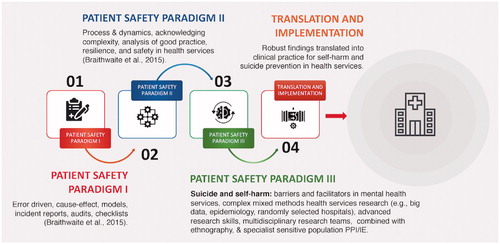

Patient safety in healthcare is a global priority (WHO, Citation2017) and there is a substantial body of patient safety research in general hospital services (Braithwaite, Wears, & Hollnagel, Citation2015). The predominant paradigm (Patient Safety paradigm I), focuses on “unintended or unexpected incidents that could have or did lead to harm for one or more patients receiving NHS funded-healthcare” (National Patient Safety Agency, Citation2006, p.15). Traditional patient safety methods such as root cause analysis, incident reporting, risk management, record review, and checklists are used to understand and reduce clinician error and avoidable harm (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015). However, patient safety is more than the documented errors and adverse events reporting (Brickell et al., Citation2009). Healthcare systems are dynamic and complex, which traditional patient safety incident approaches maybe ill-equipped to capture (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015). This is particularly relevant to mental health services given the complex needs of this population (Brickell et al., Citation2009).

There is a second wave of patient safety research (Patient Safety paradigm II) that focuses on the reality of “work in practice” – an in situ approach that seeks to better understand how clinicians provide good quality healthcare in real-time dynamic systems (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015). The focus is on the interaction between patient care, environmental contexts, and healthcare culture, rather than placing further burden on staff via additional checklists and other bureaucratic processes (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015). Both approaches to patient safety in healthcare systems are complementary, and when combined with patient, carer, and clinician involvement, have the potential to increase our understanding of patient safety and suicidal behaviour.

Patient safety research in mental health

In England, there were 7,021,645 reported incidents where patients received some level of harm due to their medical care between the 1 April 2014 and the 3 March 2019. Most of these occurred in acute services (75.5%) and mental health services (17.3%). Of the total incidents, 15,790/7,021,645 resulted in loss of life (0.22%). Over half of these deaths occurred in mental health services (9,013/15,790, 57%) (NHS Improvement, Citation2014–2019, National Organisational Data). Globally, there are significant gaps what we know about avoidable harm in mental healthcare services. Panagioti and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings internationally. The pooled prevalence for preventable harm was 6% across health services. Most preventable harm took place in general hospitals and was more prevalent in intensive care or surgery. However, of the 70 papers reviewed, there were no published papers on avoidable harm in psychiatry and only two in primary care (Panagioti et al., Citation2019).

The lack of patient safety research in mental health services may be due to differences in the nature and type of avoidable harm (Panagioti et al., Citation2019) and the complexity or specific safety needs in mental health services (Berzins, Baker, Brown, & Lawton, Citation2018; Brickell et al., Citation2009; Dewa et al., Citation2018). National UK incident report data suggests some issues are common across all health services while others occur more frequently in mental health. Common patient safety incidents across specialties include accidents, and errors in medication prescribing, admission, and transfer (National Patient Safety Agency, Citation2006; NHS Improvement, Citation2018). Incidents that are more specific to mental health services include interpersonal aggression and self-harm, defined as any self-poisoning or self-injury irrespective of motivation or intent (NICE, Citation2011). Self-harm is the most common incident in mental health services and accounts for 27% of all reported patient safety events (NHS Improvement, Citation2018). Around 30% of these incidents result in death (NHS Improvement, Citation2018). While many of these are subject to individual case reviews, there is little systematic research in this area.

Patient safety in mental health has been examined as part of wider research into physical health or quality improvement initiatives (e.g., Brickell et al., Citation2009; Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Citation2019; National Patient Safety Agency, Citation2006) rather than being a topic that is investigated in its own right (Dewa et al., Citation2018). This approach now seems to be changing. Researchers have highlighted priorities for patient safety, including suicide prevention, communication errors, and a safety culture (Berzins et al., Citation2018; Dewa et al., Citation2018). Other research demonstrates the importance of perceptions of safety amongst mental health staff (Hamaideh, Citation2017), patient involvement in mental health care safety (Berzins et al., Citation2018) and staff burnout (Hall et al., Citation2016).

The recent rise in the volume of patient safety research conducted in mental health services is welcomed but it remains sparse compared to the amount of such research conducted in general healthcare settings (Dewa et al., Citation2018). Suicide prevention should be an international priority for patient safety research (Dewa et al., Citation2018), but few studies have applied patient safety paradigms to advance understanding of preventing suicide in those accessing mental health services. Innovation and careful thought are needed to apply patient safety paradigms to suicide prevention and self-harm research. The context and safety issues are different to those in acute care services. Mental health services manage patient populations with complex social and psychiatric needs. Patients with mental health problems are more likely to have experienced financial difficulties, debt, housing issues and unemployment, which may complicate care planning (Evans, Citation2018; Gunasinghe et al., Citation2018; Richardson, Jansen, & Fitch, Citation2018). Mental capacity can fluctuate due to psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress and patients may refuse treatment (Quinlivan et al., Citation2019). Seclusion and restraint are more common than in acute services, and treatments can be given in various environments such as inpatient wards, crisis, community, or home treatment teams, and/or liaison psychiatry services (Brickell et al., Citation2009). Mental health services are often highly pressured and focussed on risk. Staff may feel disempowered with high workloads, excessive administrative demands, and emotional strain. Burnout and compassion fatigue are commonly experienced and can negatively affect care and patient safety (Towey-Swift & Whittington, Citation2019).

Self-harm is an urgent patient safety issue

Patient safety in mental health services might focus on a number of areas. Incidents of inpatient sexual abuse, violence, aggression, restraint, medication errors and/or incidents due to unsafe wards (e.g., ligature points, absconding, poor quality observations and transitions) are likely to have detrimental and traumatic effects on patients and staff (Care Quality Commission, Citation2018; Brickell et al., Citation2009). However, self-harm is the incident most likely to result in death (usually by suicide), and is therefore a key safety concern (National Patient Safety Agency, Citation2006).

Self-harm is a common reason for hospital presentation internationally (Arensman et al., Citation2018; Conner, Langley, Tomaszewski, & Conwell, Citation2003; Claassen et al., Citation2006; Finkelstein et al., Citation2015; Skinner et al., Citation2016). One in 300 presentations to the emergency department are for self-poisoning in the United States (Finkelstein et al., Citation2015) and at least 200,000 episodes of self-harm are treated in emergency departments annually in England (Hawton et al., Citation2007). Repeat self-harm is common and associated with a greatly elevated risk of subsequently dying by suicide (Carroll, Metcalfe, & Gunnell, Citation2014; Finkelstein et al., Citation2015). Around 16 per cent of patients will repeat self-harm within one year and one in ten may harm themselves within five days of the initial episode (Carroll et al., Citation2014; Kapur et al., Citation2006). Methods of self-harm may also change and escalate to more lethal means (Witt, Daly, Arensman, Pirkis, & Lubman, Citation2019). Several large epidemiological studies based on UK primary care cohorts (Carr et al., Citation2016; Morgan et al., Citation2017); multicentre monitoring projects of self-harm (Geulayov et al., Citation2018); national UK wide surveys (McManus et al., Citation2019) and national data linkage studies in Wales (Marchant et al., Citation2019) indicate that rates of self-harm particularly in young people may be increasing. Internationally, similar rising rates of self-harm have been found in Australia (Perera et al., Citation2018), the United States (Westers, Citation2019), and Ireland (Griffin et al., Citation2018). Understanding self-harm as a patient safety issue may help to prevent repeat self-harm and suicide whilst also improving healthcare services (Department of Health (England), Citation2017).

What do we know about safer mental health services?

Despite the general lack of mental health patient safety research, there is international literature investigating components of mental health services which may be associated with reductions in suicide (e.g., Carroll et al., Citation2014; Hunt et al., Citation2014; Kapusta et al., Citation2009; Kapur et al., Citation2015; Pirkola, Sund, Sailas, & Wahlbeck, Citation2009; Quinlivan et al., Citation2017; Tondo, Albert, & Baldessarini, Citation2006; While et al., Citation2012). For example, in our own research, we found that the implementation of evidence-based recommendations (e.g., assertive outreach, removal of ligature points, 24-hour crisis teams) from the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health in England were associated with a reduction in suicide risk in mental health services (While et al., Citation2012). In Finland, well developed community services with 24-hour emergency services and outpatient services were associated with lower suicide rates in a nationwide study of adult mental health services (Pirkola et al., Citation2009). Several studies have highlighted the importance of psychosocial assessments and psychological treatments in reducing repeat self-harm (e.g., Hawton et al., Citation2016; Steeg, Emsley, Carr, Cooper, & Kapur, Citation2018), and evidence against the use of risk scales for predicting repeat self-harm, suicide or determining patient management (e.g., Carter et al., Citation2017; Chan et al., Citation2016; Quinlivan et al., Citation2017).

However, despite the growing evidence-base, policy (NICE, Citation2011), and recent competency frameworks (e.g., Health Education England, Citation2018), which outline training needs for staff, much still needs to be done to address the gap between evidence and implementation in hospital and in the transition across services. Implementation rates of clinical recommendations are highly variable across hospital services (Cooper et al., Citation2013; While et al., Citation2012) and there is clear evidence that, contrary to an unequivocal NICE “do not do” recommendation (NICE, Citation2011), a sizeable proportion of GPs prescribe highly toxic tricyclic antidepressants to patients who are known to have recently harmed themselves (Carr et al., Citation2016). Healthcare services differ in their ability to surmount obstacles and provide good quality care (Care Quality Commission, Citation2018). Rates of assessment and aftercare following self-harm vary widely and are relatively low across hospitals (Cooper et al., Citation2013) but demand is increasing (Care Quality Commission, Citation2019).

A new way forward– patient safety III?

A new paradigm for patient safety in mental health services might be helpful, combining expertise in complex large scale applied health research with innovative patient safety I and II approaches that are strong on implementation, patient involvement, and improvement science. We are aiming to do exactly this through the mental health components of the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. We will address real world issues in clinical services, and move to the next level of implementing robust evidence. Patients, carers, and staff are essential to improving safety in health services, and are represented in patient safety paradigms. However, patient involvement in suicide prevention research may lag behind involvement in research in other patient safety paradigms possibly due to the sensitivity of the topic and patient vulnerabilities (Littlewood et al., Citation2019). Working closely with patients, carers, mental health staff, and clinical services, it needs to be ensured that any findings are grounded in the reality of clinical practice and will directly feedback into front-line patient safety issues. Our initial focus will be family involvement in clinical care and understanding gaps in service provision for self-harm. We will investigate barriers and facilitators to good quality care through mixed methods and multi-site hospital studies, including large scale epidemiological database studies, national patient/carer interviews and surveys, and ethnography, all supported with strong patient/public involvement. We anticipate that this will lead to new insights which will help to push forward implementation in self-harm and suicide prevention research. Our findings will contribute the future design of mental health services and better care for patients who present to those services ().

Conclusion

Suicide is preventable and health services have an important role to play in reducing its incidence as part of wider population and public health measures. Patients in contact with mental health services and those who present to hospital following self-harm are vulnerable groups at greatly elevated risk of subsequently dying by suicide. Despite decades of research and some progress in terms of safer mental health services (e.g., NICE, Citation2011; While et al., Citation2012), there are wide differences across services in the quality of care for people who are in contact with mental health services or who have harmed themselves. Combining mental health, public health, and patient safety research paradigms will provide new opportunities and interventions to close the implementation gap between evidence, policy and practice and ultimately reduce the number of suicide deaths.

Disclosure statement

NK is a member of the Department of Health’s (England) National Suicide Prevention Advisory Group. He chaired the NICE guideline development group for the longer-term management of self-harm. NK is currently chair of the committee for the updated NICE guideline for Depression and Topic Advisor for the new NICE self-harm guideline. He is also supported by the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arensman, E., Griffin, E., Daly, C., Corcoran, P., Cassidy, E., & Perry, I. J. (2018). Recommended next care following hospital-treated self-harm: Patterns and trends over time. PLoS One, 13(3), e0193587. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193587

- Berzins, K., Baker, J., Brown, M., & Lawton, R. (2018). A cross‐sectional survey of mental health service users’, carers’ and professionals’ priorities for patient safety in the United Kingdom. Health Expectations, 21(6), 1085–1094. doi:10.1111/hex.12805

- Braithwaite, J., Wears, R. L., & Hollnagel, E. (2015). Resilient health care: Turning patient safety on its head. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 27(5), 418–420. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzv063

- Brickell, T.A., Nicholls, T.L., Procyshyn, R.M., McLean, C., Dempster, R.J., Lavoie, J.A.A., … Wang, E. (2009). Patient safety in mental health. Edmonton: Canadian Patient Safety Institute and Ontario Hospital Association.

- Care Quality Commission (2018). Sexual safety on mental health wards. September 2018. Care Quality Commission. UK. Retrieved from https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20180911c_sexualsafetymh_report.pdf.

- Care Quality Commission (2019). The state of health care and adult social care in England 2018/2019. UK: Crown Copyright.

- Carr, M. J., Ashcroft, D. M., Kontopantelis, E., Awenat, Y., Cooper, J., Chew-Graham, C., … Webb, R. T. (2016). The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001–2013. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 53. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0753-5

- Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 9(2), e89944. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- Carter, G., Milner, A., McGill, K., Pirkis, J., Kapur, N., & Spittal, M. J. (2017). Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: Systematic review and meta-analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 387–395. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182717

- Chan, M. K. Y., Bhatti, H., Meader, N., Stockton, S., Evans, J., O’Connor, R. C., … Kendall, T. (2016). Predicting suicide following self-harm: Systematic review of risk factors and risk scales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 277–283. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.170050

- Claassen, C. A., Trivedi, M. H., Shimizu, I., Stewart, S., Larkin, G. L., & Litovitz, T. (2006). Epidemiology of nonfatal deliberate self-harm in the United States as described in three medical databases. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(2), 192–212. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.2.192

- Conner, K. R., Langley, J., Tomaszewski, K. J., & Conwell, Y. (2003). Injury hospitalization and risks for subsequent self-injury and suicide: A national study from New Zealand. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1128–1131. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1128

- Cooper, J., Steeg, S., Bennewith, O., Lowe, M., Gunnell, D., House, A., … Kapur, N. (2013). Are hospital services for self-harm getting better? An observational study examining management, service provision and temporal trends in England. BMJ Open, 3(11), e003444. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003444

- Department of Health (England). (2017). Preventing suicide in England: Third progress report on the cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives. UK: Crown Copyright.

- Dewa, L. H., Murray, K., Thibaut, B., Ramtale, S. C., Adam, S., Darzi, A., & Archer, S. (2018). Identifying research priorities for patient safety in mental health: An international expert Delphi study. BMJ Open, 8(3), e021361. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021361

- Evans, K. (2018). Treating financial difficulty–the missing link in mental health care? Journal of Mental Health, 27(6), 487–489. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1520972

- Finkelstein, Y., Macdonald, E. M., Hollands, S., Sivilotti, M. L. A., Hutson, J. R., Mamdani, M. M., Koren, G., … Canadian Drug Safety and Effectiveness Research Network (CDSERN). (2015). Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(6), 570–575. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3188

- Geulayov, G., Casey, D., McDonald, K. C., Foster, P., Pritchard, K., Wells, C., … Hawton, K. (2018). Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal self-harm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): A retrospective study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(2), 167–174. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30478-9

- Griffin, E., McMahon, E., McNicholas, F., Corcoran, P., Perry, I. J., & Arensman, E. (2018). Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: A 10-year national registry study 2007–2016. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(7), 663–671. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1

- Gunasinghe, C., Gazard, B., Aschan, L., MacCrimmon, S., Hotopf, M., & Hatch, S. L. (2018). Debt, common mental disorders and mental health service use. Journal of Mental Health, 27(6), 520–528. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1487541

- Hall, L. H., Johnson, J., Watt, I., Tsipa, A. & O'Connor, D. B., (2016). Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PloS one, 11(7), e0159015.

- Hamaideh, S. H. (2017). Mental health nurses’ perceptions of patient safety culture in psychiatric settings. International Nursing Review, 64(4), 476–485. doi:10.1111/inr.12345

- Hawton, K., Bergen, H., Casey, D., Simkin, S., Palmer, B., Cooper, J., … Owens, D. (2007). Self-harm in England: A tale of three cities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(7), 513–521. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0199-7

- Hawton, K., Witt, K. G., Salisbury, T. L. T., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Hazell, P., … van Heeringen, K. (2016). Psychosocial interventions following self-harm in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 740–750. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30070-0

- Health Education England. (2018). Self-harm and suicide prevention competence framework: Adults and older adults. UK: National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health.

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. (2019). Scottish Patient Safety Programme: Mental health. Retrieved from https://ihub.scot/improvement-programmes/scottish-patient-safety-programme-spsp/spsp-mental-health/.

- Hunt, I. M., Rahman, M. S., While, D., Windfuhr, K., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2014). Safety of patients under the care of crisis resolution home treatment services in England: A retrospective analysis of suicide trends from 2003 to 2011. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(2), 135–141. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70250-0

- Kapur, N., Cooper, J., King-Hele, S., Webb, R., Lawlor, M., Rodway, C., & Appleby, L. (2006). The repetition of suicidal behavior: A multicenter cohort study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(10), 1599–1609. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n1016

- Kapur, N., Steeg, S., Turnbull, P., Webb, R., Bergen, H., Hawton, K., … Cooper, J. (2015). Hospital management of suicidal behaviour and subsequent mortality: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(9), 809–816.

- Kapusta, N. D., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Etzersdorfer, E., Voracek, M., Dervic, K., Jandl‐Jager, E., & Sonneck, G. (2009). Influence of psychotherapist density and antidepressant sales on suicide rates. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119(3), 236–242. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01314.x

- Littlewood, D.L.L., Quinlivan, L., Steeg, S., Bickley, H., Rodway, C., Bennett, C., … Kapur, N. (2019). Evaluating the impact of patient and carer involvement in suicide and self-harm research: A mixed-methods, longitudinal study protocol. Health Expectations, 1–7. doi:10.1111/hex.13000

- Marchant, A., Turner, S., Balbuena, L., Peters, E., Williams, D., Lloyd, K., … John, A. (2019). Self-harm presentation across healthcare settings by sex in young people; an e-cohort study using routinely collected linked healthcare data in Wales, UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1–8. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-317248

- McManus, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, C., Bebbington, P. E., Howard, L. M., Brugha, T., … Appleby, L. (2019). Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: Repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(7), 573–581. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30188-9

- Morgan, C., Webb, R. T., Carr, M. J., Kontopantelis, E., Green, J., Chew-Graham, C. A., … Ashcroft, D. M. (2017). Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ, 359, j4351. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4351

- National Patient Safety Agency. (2006). With safety in mind: Mental health services and patient safety. Patient Safety observatory Report. July 2006. National Patient Safety Agency. UK. Retrieved from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090218135132/http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/nrls/.

- NHS Improvement. (2014–2019). Organisational patient safety incident reports: Data workbooks September 2014. UK: NHS Improvement. Retrieved from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20171030124651/http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=135261https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/organisation-patient-safety-incident-reports-data/#h2-data-workbooks-and-commentary-official-statistics.

- NHS Improvement. (2018). NRLS national patient safety incident reports: Commentary, September 2018. UK: NHS Improvement. Retrieved from https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/3266/NAPSIR_commentary_FINAL_data_to_March_2018.pdf. [Accessed 21 February 2019]

- NICE. (2011). Self-harm. The NICE guideline on longer-term management. National clinical guideline number 133. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- Panagioti, M., Khan, K., Keers, R. N., Abuzour, A., Phipps, D., Kontopantelis, E., … Ashcroft, D. M. (2019). Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 366, l4185. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4185

- Perera, J., Wand, T., Bein, K. J., Chalkley, D., Ivers, R., Steinbeck, K. S., … Dinh, M. M. (2018). Presentations to NSW emergency departments with self‐harm, suicidal ideation, or intentional poisoning, 2010–2014. Medical Journal of Australia, 208(8), 348–353. doi:10.5694/mja17.00589

- Pirkola, S., Sund, R., Sailas, E., & Wahlbeck, K. (2009). Community mental-health services and suicide rate in Finland: A nationwide small-area analysis. The Lancet, 373(9658), 147–153. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61848-6

- Pitman, A., Osborn, D., King, M., & Erlangsen, A. (2014). Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 86–94. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X

- Quinlivan, L., Cooper, J., Meehan, D., Longson, D., Potokar, J., Hulme, T., … Kapur, N. (2017). Predictive accuracy of risk scales following self-harm: Multicentre, prospective cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 429–436. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189993

- Quinlivan, L., Nowland, R., Steeg, S., Cooper, J., Meehan, D., Godfrey, J., … Kapur, N. (2019). Advance decisions to refuse treatment and suicidal behaviour in emergency care: it’s very much a step into the unknown. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 5(4), e50.

- Richardson, T., Jansen, M., & Fitch, C. (2018). Financial difficulties in bipolar disorder part 1: Longitudinal relationships with mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 27(6), 595–601. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1521920

- Skinner, R., McFaull, S., Draca, J., Frechette, M., Kaur, J., Pearson, C., & Thompson, W. (2016). Suicide and self-inflicted injury hospitalizations in Canada (1979 to 2014/15). Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 36(11), 243–251. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.36.11.02

- Steeg, S., Emsley, R., Carr, M., Cooper, J., & Kapur, N. (2018). Routine hospital management of self-harm and risk of further self-harm: Propensity score analysis using record-based cohort data. Psychological Medicine, 48(2), 315–326. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001702

- Tondo, L., Albert, M. J., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2006). Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: An ecological study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(4), 517–523. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0402

- Towey-Swift, K., & Whittington, R. (2019). Person-job congruence, compassion and recovery attitude in Community Mental Health Teams. Journal of Mental Health. doi:10.1080/09638237.2019.1608931

- Westers, N. J. (2019). Not a fad: Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(4), 831–846. doi:10.1177/2F1359104519873496

- While, D., Bickley, H., Roscoe, A., Windfuhr, K., Rahman, S., Shaw, J., … Kapur, N. (2012). Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997–2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1005–1012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1

- Witt, K., Daly, C., Arensman, E., Pirkis, J., & Lubman, D. (2019). Patterns of self-harm methods over time and the association with methods used at repeat episodes of non-fatal self-harm and suicide: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 250–226. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.001

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Preventing suicide. A global imperative. Luxembourg: World Health Organisation. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). Patient Safety, Making health care safer. Geneva: World Health Organisation.: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0IGO. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255507/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.11-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). National suicide prevention strategies. Progress, examples and indicators. Switzerland: World Health Organization.