Abstract

Background

Emotional safety is particularly important for people living with dementia. Although there have been efforts to define this concept, no systematic review has been performed.

Aim

We aimed to identify and analyze the knowledge available over a 10-year period regarding the emotional safety of people living with dementia to concretize this phenomenon.

Methods

Seven databases were searched. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies published between November 2007 and October 2017 were included. Study selection and critical appraisal were performed by two reviewers. A content analysis of the qualitative data and a descriptive analysis of the quantitative data were performed.

Results

In total, 27 publications (n = 26 studies) were included. The following five main categories were identified: (1) “emotional safety as a primary psychological need”; (2) “emotional safety in the context of disease-related, biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors”; (3) “inner conditions and strategies”; (4) “outer conditions and strategies”; and (5) “emotional safety as a condition”.

Conclusion

People living with dementia appear to be particularly vulnerable to decreased emotional safety. Research should focus on achieving a comprehensive understanding of their emotional safety needs.

Introduction

Safety is described as a basic human need that can be compromised by various factors, e.g. disease-related factors (Maslow, Citation1943). Living with dementia can also be related to safety issues (Zingmark et al., Citation2002). Dementia is mostly a progressive, chronic syndrome characterized by cognitive dysfunction (e.g. memory problems) that affects certain abilities that are required in everyday life (World Health Organization, Citation2012). The consequences of this disease can contribute to decreased feelings of safety (Sørensen et al., Citation2008). However, feeling safe enables people living with dementia to act independently and to maintain relationships even at an early stage of the disease (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). In contrast, a decreased feeling of safety is associated with fear in the context of perceived dependencies (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). Hence, emotional safety appears to be an important topic for people living with dementia.

The concept of “emotional safety” has been described in relation to various settings. In nursing settings, emotional safety has been a topic in the field of patient safety in home care (Lang et al., Citation2008). In addition to physical, social and functional safety, emotional safety is considered a key dimension of patient safety; it “refers to the psychological impact of receiving/providing [health care] services” (Lang et al., Citation2008, p. 132). Research on emotional safety in nursing and health services settings considers it in various contexts such as support groups (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013) and special care units (Zingmark et al., Citation2002). In therapeutic and educational settings, the definition of emotional safety is based on the context of adventure therapy (Vincent, Citation1995). Vincent (Citation1995, p. 76) reported that emotional safety “can be measured on a continuum from feeling threatened to feeling safe”. According to this definition, emotional safety depends on trust in oneself and in others (Vincent, Citation1995). However, a specific definition of emotional safety in the context of dementia is currently lacking. Therefore, based on existing research (Lang et al., Citation2008; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Vincent, Citation1995; Zingmark et al., Citation2002), we defined emotional safety in the field of dementia as the experience of people living with dementia on a continuum between feeling safe and feeling threatened in the context of subjectively perceived inner and outer conditions.

Panke-Kochinke (Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2016) provided a further basis for the concept of emotional safety by proposing the “model of inner security”. This disease-specific model of actions related to coping focuses on the search for “inner security” in relationships. During the early stages of dementia, people are faced with dependencies and perceived incapacitation that appear in their relationships with others. The aim is to achieve a balance between the need for “security”, the degree of support that provides feelings of safety, and feelings of fear related to external control. Fear in this context has been described more often as a fear of control and restriction rather than as a fear of an increase in symptoms such as forgetfulness (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2014). Achieving a perceived beneficial balance, e.g. by following familiar everyday routines, can improve the quality of life of people living with dementia (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2014, Citation2016). However, this perceived balance can be disturbed by confrontation with stigmatization (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2014). Therefore, the needs of people living with dementia appear to be central to understanding the process of searching for safety.

In addition, in terms of person-centered care, Kitwood (Citation1993a, Citation1993b, Citation1997) emphasizes the necessity of addressing people living with dementia by considering the “complex interaction” among the unique factors associated with each person. These factors include personality (e.g. coping styles), biography, physical health status, neurological impairment and social psychology (Kitwood, Citation1993a, Citation1997). In the context of emotional safety, social psychology refers to both positive (e.g. acceptance) and negative (e.g. stigmatization) experiences in everyday life that influence the maintenance of personhood, and such experience “enhances or diminishes an individual’s sense of safety” (Kitwood, Citation1993a, p. 542).

However, only a few empirical studies have focused on the conditions of emotional safety needs. Although there have been some efforts to describe emotional safety, no systematic review that describes this concept in the context of people living with dementia has been performed. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to identify and analyze the knowledge available over a 10-year period regarding the emotional safety of people living with dementia to concretize the phenomenon of emotional safety.

Materials and methods

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., Citation2009) and is registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42018082697).

Data sources and search strategy

We performed a systematic literature search using the following general and specialist electronic bibliographic databases: MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE via Scopus, CINAHL Plus via EBSCOhost, PsycINFO via EBSCOhost, PSYNDEX via EBSCOhost, the Cochrane Library and Journals@Ovid via Ovid. To enhance the sensitivity of the search strategy, we employed search terms related to five core components (“dementia”, “safety”, “emotion”, “needs” and “well-being”); these terms which were combined in three ways (for the full electronic search strategy, see Appendices A and B). The search component “dementia” is linked to all three combinations of terms and includes all types of dementia. First, we combined the search terms of the components “dementia”, “safety” and “emotion”. To increase the sensitivity of the search strategy, we added the component “needs” as an alternative to “safety”. The search terms of the component “safety” were not always included in the title or abstract of the searched publications, but “needs” was mentioned as a main theme. We added the terms of the component “well-being” as an alternative to “emotion” because some studies have reported that emotional safety is related to living well with dementia (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Zingmark et al., Citation2002). Second, “dementia” was combined with the terms “safety” and “needs”, and third, “dementia” was combined with the terms “emotion” and “well-being” to obtain further variations and to strengthen the sensitivity of the search strategy.

We used database specific Medical Subject Headings. We also used keywords that have been published in other reviews (Farina et al., Citation2017; Steeman et al., Citation2006) or that appear in the definitions described above in other settings (Lang et al., Citation2008; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Vincent, Citation1995; Zingmark et al., Citation2002). We pretested our search strategy, and three authors performed a title-abstract screening of the first 200 hits. On this basis, we discussed and adjusted the search strategy by adding the term “security” to our search strategy (Appendix A). We also conducted a backward citation tracking of eligible studies and performed forward citation tracking using Google Scholar (Bakkalbasi et al., Citation2006).

Eligibility criteria

Studies that report or discuss the emotional safety of people living with dementia from several perspectives, e.g. the perspectives of people living with dementia and those of their informal and formal caregivers, were included. We have also included the perspectives of stakeholders (e.g. physicians, social workers and volunteers) to ensure a comprehensive view of emotional safety as a complex phenomenon.

We included studies published between November 2007 and October 2017 as a means of identifying current publications related to the emotional safety of people living with dementia. Only studies published in English or German were included. There were no restrictions regarding the type of study design eligible for inclusion. Gray literature was included only in the form of dissertations. We did not exclude studies of poor quality.

Study selection

We removed duplicates and verified the inclusion dates. We used database-specific filters for the publication dates when available. The titles and abstracts of all identified hits were screened independently by two reviewers. In total, three reviewers were involved. The hits were categorized as “included”, “excluded” or “unclear”. In cases of uncertainty, a third reviewer was consulted. The full text of the hits that were categorized as “included” or “unclear” was reviewed by two reviewers. Eligible studies were subsequently included. We also analyzed the reference lists of systematic reviews that addressed emotional safety as a means of identifying additional publications. Backward citation tracking was performed by screening the references of the eligible included studies.

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted the following data from the primary sources as a means of organizing and comparing the specific methodological characteristics of the identified studies (): author, year of publication, approaches and data collection methods, sample size, included participants, participant characteristics (age and sex), setting, recruitment, country, study focus and main findings regarding emotional safety. The data extraction was based on the study results pertaining to the emotional safety of people living with dementia. We developed a matrix in which the results are presented at different levels of abstraction, including perspectives and content, and used it to compare the data. All of the extracted data described above were critically discussed by the review team.

Table 1. Overview of the included studies.

Consistent with an integrative review approach (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005), we performed data reduction and illustrated, compared and consolidated the data. Finally, we drew conclusions. We initiated the data reduction by classifying the identified studies and developed subgroups based on the study designs.

The data abstraction was performed via a predominantly qualitative data synthesis ( and ). The qualitative data were analyzed using a qualitative content analysis synthesis design (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Hong et al., Citation2017). The following two strategies were used for the synthesis of qualitative data: (i) a primary inductive content analysis was used to identify categories related to emotional safety and (ii) a deductive content analysis was used to orientate the analysis to a working definition at a high level of abstraction, thus identifying the inner and outer conditions. In both strategies, one reviewer read the material and selected relevant sections. In both procedures, the aim was to categorize the content of the study. Data synthesis of the inductive and deductive results was performed by data clustering, making comparisons, finding patterns and highlighting relations and differences. The inductive content analysis was started by open coding. A categorization matrix was developed for the deductive procedure considering the predefined categories “inner condition” and “outer condition”.

Table 2. Inner conditions of emotional safety in people living with dementia.

A quantitative data synthesis could be not performed due to the small number of studies; therefore, quantitative data were described separately. The results were interpreted in terms of the content of the studies. Finally, all findings were critically discussed, and conclusions were drawn.

Critical appraisal

The identified studies were critically appraised by two reviewers and discussed with a third reviewer. We used the following two design-specific tools: the quality appraisal checklist provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for qualitative studies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2012) and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for quantitative and mixed-methods studies (Pace et al., Citation2012). After comparing the assessments and discussing the material, the studies were assessed using the NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2012, p. 73) checklist as “++ (All or most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled the conclusions are very unlikely to alter)”, “+ (Some of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled, or not adequately described, the conclusions are unlikely to alter)” and “– (Few or no checklist criteria have been fulfilled and the conclusions are likely or very likely to alter)”.

The Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group reported the following three approaches to dealing with the results of the critical appraisal: (i) “include or exclude a study”; (ii) “give more weight to studies that scored high on quality”; and (iii) “describe what has been observed without excluding any studies” (Hannes, Citation2011, p. 11 – 12). Although the group recommends approaches (i) and (ii), they state that the decision must be made individually and that each approach has its value. Consistent with the recommended procedure for conducting a sensitivity analysis by Hannes (Citation2011), we did not find any differences between the lower-quality studies and the higher-quality studies in the content of their results. However, the lower-quality studies provide more detailed information on emotional safety. Furthermore, there was a paucity of evidence addressing our research question. Additionally, emotional safety was not mentioned as a primary outcome in any of our identified studies. To ensure transparency and provide readers with a comprehensive overview of the current state of the studies, we have decided to report studies of all quality levels to highlight the research needs and not to exclude any of the studies.

Results

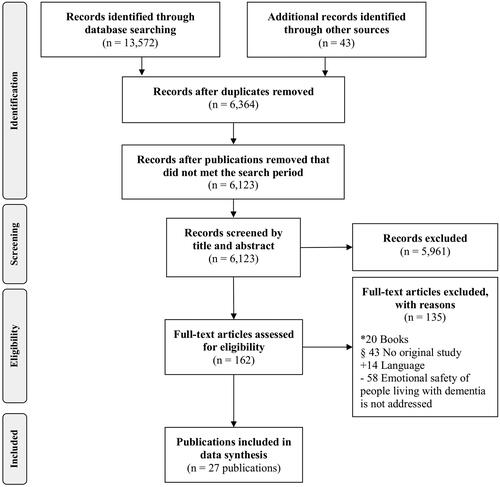

In total, 13,572 records were identified through the database search, and 43 records were identified through other sources (including identified references in systematic reviews; ). After removing the duplicates and publications that did not fall within the search period, we reviewed 6123 publications published between November 2007 and October 2017. In total, 27 publications (n = 26 studies) were finally included. Two of these studies (Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Lawrence et al., Citation2011) were identified through a “snowball” search strategy using the publications of Brorsson et al. (Citation2013) and Perrar et al. (Citation2015). One study (Hung et al., Citation2017) was found in other sources.

Figure 1. Study selection process (PRISMA-Statement) (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Details of the identified studies are presented in . In total, 22 studies used qualitative methods, two used quantitative methods and two used a mixed-methods design. One of the two quantitative studies reported quantitative results in the context of emotional safety. The authors of the second study presented no results related to emotional safety but discussed their results in this context. None of the included studies reported the emotional safety of people living with dementia as the primary study focus.

Most studies involved an in-depth interpretative or reconstructive approach, e.g. a phenomenological or ethnographic approach. For example, the data collection was performed through in-depth interviews, observation and group interviews. The sample size varied from four to 169 participants.

Participants with a variety of characteristics were included in the identified studies. Twelve studies included people living with dementia, seven studies included both people living with dementia and other proxies and six studies included proxies, e.g. family members and friends, health care providers, and other staff. One study included both people living with dementia and people living with mild cognitive impairment. The most frequently reported types of dementia in these studies were Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (n = 10) and vascular dementia (n = 6). Most studies (n = 12) involved people with early or mild dementia. Nine studies included people with moderate dementia, and six studies included people with severe or advanced dementia. In total, five studies did not specify the stage of dementia.

The most frequently reported settings in these studies (n = 15) involved people with dementia who were living at home or in community dwellings. In this context, the main focus is on participation in public life and receipt of health services. In addition, a residential care/nursing home setting and a hospital setting were reported. The participants in the studies were recruited in Europe (n = 20), the USA (n = 2), Asia (n = 2) and Canada (n = 2).

The critical appraisal showed that five studies fulfilled all or most of the criteria, 14 fulfilled some of the checklist criteria and seven fulfilled few or none of the criteria.

Emotional safety in the context of people living with dementia

The following five main categories of emotional safety were identified: (1) “emotional safety as a primary psychological need”; (2) “emotional safety in the context of disease-related, biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors”; (3) “inner conditions and strategies”; (4) “outer conditions and strategies”; and (5) “emotional safety as a condition”.

Emotional safety as a primary psychological need

Four identified studies addressed the phenomenon of emotional safety as a primary psychological need and included the perspectives of people living with dementia and those of health care providers and family caregivers. Similar to physical safety (Hung et al., Citation2017), emotional safety is described as a primary need among people living with dementia (Hansen et al., Citation2017). We identified the following four dimensions of emotional safety: feeling psychologically safe (Hung et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2015), feeling economically safe (Wang et al., Citation2015), feeling socially safe (Hansen et al., Citation2017) and feeling physically safe (Hansen et al., Citation2017). People living with dementia can express their “unmet needs” to feel safe in different ways, such as engaging in disruptive behavior (Wang et al., Citation2012; Citation2015). According to Wang et al. (Citation2012, Citation2015), the need to feel economically safe can be expressed through hoarding behavior. Additionally, repetitive behavior, altered eating behavior and delusions have been described as indicators of the need to feel psychologically safe.

Emotional safety in the context of disease-related, biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors

A total of nine studies reported that changes and difficulties due to dementia can threaten the feeling of safety. Most studies solely interviewed people living with dementia (n = 7). Two studies also included other perspectives (family members and staff members).

Living with forgetfulness (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Citation2013; Hung et al., Citation2017; Mazaheri et al., Citation2014; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Sørensen et al., Citation2008) was related to changes such as not remembering passwords (Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Citation2013) and encountering “new” places that had previously been perceived as familiar but were gradually forgotten (Sørensen et al., Citation2008). Another mentioned change was difficulty in focusing attention due to the presence of too many stimuli (Brorsson et al., Citation2013; Hung et al., Citation2017), e.g. street noises (Brorsson et al., Citation2013) or the presence of many people in the immediate surroundings (Hung et al., Citation2017). Difficulties were reported in retrieving learned behaviors (Brorsson et al., Citation2013; Sørensen et al., Citation2008) that were easily followed in the past but were currently difficult or no longer possible due to dementia (Sørensen et al., Citation2008), e.g. correct behavior while crossing a road (Brorsson et al., Citation2013). Two studies showed communication difficulties (Hung et al., Citation2017; Sørensen et al., Citation2008), e.g. problems understanding several words (Sørensen et al., Citation2008). In addition, people living with dementia were reported to feel unsafe because things that previously created a feeling of safety, such as control and independence, are restricted in the course of dementia (Osborne et al., Citation2010). According to Osborne et al. (Citation2010), people who experience these restrictions are less able to cope with the disease. Living in the present and following routines appear to be strategies for coping with dementia-related changes in the context of emotional safety (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Yatczak, Citation2014).

Five studies of people living with dementia or family members reported that biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors related to the emotional safety of people living with dementia should be considered in the context of emotional safety. Four studies concluded that past experiences without dementia may have an effect on the experience of emotional safety in the current situation (Mazaheri et al., Citation2014; Osborne et al., Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2012; Citation2015).

Women seem to have a greater need for safety (Wang et al., Citation2015) and to be at higher risk for a decreased feeling of safety (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013) than men. Wang et al. (Citation2015) explained this observation from a biographical perspective as follows: women are often assigned a certain social role and often experience dependency on their families or husbands. Another biographical factor is related to individuals’ experiences with living in their own country or in a foreign country. Mazaheri et al. (Citation2014) interviewed Iranian people who lived in Sweden about their experiences with dementia. The participants reported high feelings of safety in public spaces, a finding that differs from the results of other studies involving people who lived in their own countries. The differences among these countries in terms of cultural factors and health care systems appear to have an impact on perceived safety (Mazaheri et al., Citation2014).

From a demographic perspective, women generally consider their male partners protectors against the disease (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). A male partner who does not behave according to this role (e.g. by having a negative response to forgetfulness) could increase feelings of insecurity in people living with dementia (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013).

A socioeconomic factor related to experiences with prior financial crises has been reported to strengthen the desire to feel safe in the present and is expressed by behaviors such as hoarding (Wang et al., Citation2012, Citation2015).

Inner and outer conditions and strategies for achieving emotional safety

Inner conditions and strategies were reported in 15 studies (). Eight of these studies included people living with dementia, four also considered other perspectives and three solely considered the perspectives of family members. The dimensions of the conditions include “inner conditions related to psychological aspects” and “inner conditions related to economic aspects”. Both dimensions are based on self-reported, subjectively perceived conditions that can strengthen or decrease emotional safety.

Seven main “inner conditions related to psychological aspects” were identified: “perceived self-efficacy and self-determination” (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Ericsson et al., Citation2013; Mazaheri et al., Citation2014; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013), “willingness to receive support” (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013), “perceived dependency on others” (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013), “perceived mental stability” (Wang et al., Citation2015), “perceived familiarity” (Brittain et al., Citation2010; Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Duggan et al., Citation2008; Genoe, Citation2009; Genoe & Dupuis, Citation2011), “perceived information need” (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013) and “assurance that others care for PLWD” (Brorsson et al., Citation2013; Cronfalk et al., Citation2017; Hung et al., Citation2017; Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Nijhof et al., Citation2013). These conditions were often reported in a context or setting related to the use of outdoor environments and to interacting with others, e.g. relatives, professionals and other people living with dementia. The self-reported strategies are related to several different aspects, including strategies involving visual/technical aids and other people for support and strategies that are employed only by people living with dementia.

Three main “inner conditions related to economic aspects” were identified: “perceived material stability and control” (Wang et al., Citation2012, Citation2015), “perceived preparedness for possible situations” (Wang et al., Citation2012) and “fear of being exploited by others” (Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). The expression of feelings of decreased economic safety through disruptive behavior is described as an internal strategy among people living with dementia (Wang et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). The only strategy performed by other people refers to identify safety needs (Wang et al., Citation2012).

Outer conditions and strategies were reported in 23 studies (). Twelve of these studies solely included people living with dementia, five also considered other perspectives and six only considered other proxies. The conditions were divided into two dimensions, “outer conditions related to social aspects” and “outer conditions related to physical aspects”. These dimensions are characterized by situations that cannot be directly controlled by people living with dementia.

Table 3. Outer conditions of emotional safety in people living with dementia.

Two “outer conditions related to social aspects” were identified: “opportunity to interact socially” (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Faith, Citation2014; Hansen et al., Citation2017; Hung et al., Citation2017; Hynninen et al., Citation2015; Mazaheri et al., Citation2014; Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Sørensen et al., Citation2008) and “receiving support” (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Cronfalk et al., Citation2017; Ericsson et al., Citation2013; Hung et al., Citation2017; Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2015). The first category comprises the following three conditions related to the basics of social interaction among people: “attitude towards people living with dementia” (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Mazaheri et al., Citation2014; Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013), “behavior of others” (Hansen et al., Citation2017; Hung et al., Citation2017; Sørensen et al., Citation2008) and “living in relationships” (Faith, Citation2014; Hynninen et al., Citation2015). The second category is related to the special care situation and focuses on the implementation and receipt of support. This category includes “establishing relationships in care” (Ericsson et al., Citation2013), “performing stressful tasks” (Brataas et al., Citation2010) and “access to help” (Cronfalk et al., Citation2017; Hung et al., Citation2017; Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2015) as the three main conditions. Only the avoidance of interactions is described as a strategy performed by people living with dementia (Cronfalk et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). The strategies performed by other people highlight the adjustment of health care services at the organizational level or at higher levels (no longer at the individual level) (Wang et al. Citation2012; Clare et al., Citation2008; Ericsson et al., Citation2013).

Six “outer conditions related to physical aspects” were identified: “time of day” (Brorsson et al., Citation2011), “background sounds/stress of noises” (Brorsson et al., Citation2013; Hung et al., Citation2017), “changing living home” (Cronfalk et al., Citation2017), “private spaces” (Genoe, Citation2009; Genoe & Dupuis, Citation2011), “building design” (Hadjri et al., Citation2015; Hung et al., Citation2017; Lawrence et al., Citation2011) and “technologies” (Brittain et al., Citation2010; Brorsson et al., Citation2011; Groenewoud et al., Citation2017; Manera et al., Citation2016; Nijhof et al., Citation2013). Various contexts and settings are considered, ranging from living at home to transitioning between home care and a nursing home. Several external strategies refer to activities of others that are intended to create a good environment for people living with dementia. In a quantitative study conducted by Manera et al. (Citation2016), a self-reported questionnaire was used to measure feelings of safety. People with mild cognitive impairment and dementia were asked how they experienced a cognitive training session using paper and virtual reality conditions (10-cm analog scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”). Under both conditions, the participants reported high feelings of safety (mean = 9.4/9.7, standard deviation = 1.3/1.1).

In five studies, the inner and outer conditions of emotional safety were described as interrelated. For example, access to help (social-related outer condition) is relevant to the emotional safety of people living with dementia, but it is also important that the individual be willing to receive support (psychological-related inner condition) (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). Brorsson et al. (Citation2013) reported that in the context of crossing roads, emotional safety in people living with dementia depends not only on the assurance that others care for them (psychological-related inner conditions) but also on existing background noise (physical-related outer condition). Despite the fact that emotional safety in such situations depends on the perception of the person living with dementia, these situations can objectively represent an increased risk of a decreased feeling of safety.

Emotional safety as a condition for people living with dementia

Emotional safety as a condition that improves the situations of people living with dementia was reported in eight studies; five of these studies involved people living with dementia, two involved people living with dementia and other proxies and one involved healthcare providers. The studies showed that emotional safety can improve psychosocial health and sociocultural well-being (Brataas et al., Citation2010; Hansen et al., Citation2017), improve everyday situations, e.g. orientation in public spaces (Brorsson et al., Citation2011, Citation2013), and enable people living with dementia to establish relationships with other people (e.g. caregivers) (Ericsson et al., Citation2013; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). Feeling safe allows people living with dementia to form relationships, perceive the support provided as good and develop themselves (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). From the caregiver’s perspective, a feeling of safety can also facilitate care in daily activities (e.g. bathing) (Hansen et al., Citation2017). In contrast, feeling unsafe can promote difficulties in orientation (Brorsson et al., Citation2011, Citation2013), increase anxiety (Hung et al., Citation2017; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013) and negatively affect (disease) coping situations (e.g. activating one’s own resources) (Hung et al., Citation2017; Osborne et al., Citation2010; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013).

Discussion

The present systematic review, which includes 27 eligible publications (n = 26 studies), is the first review to address the emotional safety of people living with dementia. The perspective of people living with dementia is well represented overall in the analyzed studies. Emotional safety as a phenomenon, including the core dimensions of psychological, economic, social and physical safety, appears to be a primary psychological need; namely, it seems to be related to relationship building and well-being. We saw that disease-related, biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors, as well as inner and outer conditions, have an impact on feelings of safety. Inner conditions related to psychological aspects and outer conditions related to social aspects were more strongly represented than inner conditions related to economic aspects and outer conditions related to physical aspects. Inner and outer conditions seem to be closely related and situational. The use of appropriate strategies can strengthen emotional safety.

Findings in the context of theoretical frameworks and other studies

In the light of the existing theories in the context of “inner security” (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2016) and “person-centeredness” (Kitwood, Citation1993a, Citation1993b, Citation1997), the perspective of people living with dementia was included in several of our identified studies. This perspective is mentioned as being highly important to improve the current understanding of the perspective of people living with dementia (Fazio et al., Citation2018; Kitwood, Citation1997) and should be included in research (von Kutzleben et al., Citation2012).

None of the identified studies address emotional safety as a primary focus of the study. This finding is surprising because several studies have reported that emotional safety is a primary psychological need and that people living with dementia represent a vulnerable group that is susceptible to a reduced feeling of safety (Bossen et al., Citation2006; Zingmark et al., Citation2002).

In the context of disease-related factors, our review showed that the emotional safety of people living with dementia can be decreased due to a loss of orientation. Steeman et al. (Citation2006, p. 732) showed that people with early-stage dementia often feel insecure because of the “incomprehensibility and unpredictability of their disease” and the changes associated with it. Based on a dementia-specific “model of inner security”, Panke-Kochinke (Citation2014) reports that living in relationships, existing skills and knowing one’s self are central. In contrast, among people with multiple sclerosis, “inner security” is related to energy balance and survival. Based on Panke-Kochinke’s results, the course of the disease can affect emotional safety. This finding is confirmed by another study showing changes in the need for safety among people living with dementia (Karlsson et al., Citation2011). Despite the increased risk, people living with dementia can also feel safe with their illness and its consequences (Mazaheri et al., Citation2014). This finding can be analyzed in more detail by referring to theoretical works, including the chronic illnesses trajectory model (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1991). The “model of inner security” postulates that individuals determine what is best for them by achieving a balance between the need for “security”, the degree of support that provides feelings of safety, and feelings of fear related to external control (Panke-Kochinke, Citation2014).

Biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors appear to be relevant to perceived emotional safety. Other authors recommend a holistic view of one’s life story (Grøndahl et al., Citation2017; Scholl et al., Citation2014). However, supporting evidence is lacking (Grøndahl et al., Citation2017). Kitwood (Citation1993b, p. 56) described past experiences in the context of interpersonal communication and personality as “a unique cluster of personal resources and psychic defences, formed in situations where the individual has had a sense of power and competence, or of impotence and threat”.

The dimensions of the inner and outer conditions are closely interrelated and must be described in their specific context. However, these associations are not described in detail in the identified studies. In addition, the results show that many conditions are present in an interactive context according to the dimensions of the individual’s psychologically related and economically related inner conditions and his or her socially related outer conditions. In the present study, emotional safety was reported in terms of the attachment style theory (Osborne et al., Citation2010). Another study proposed that promoting a good life for people living with dementia is a relationship-centered task (Zingmark et al., Citation2002). In the context of the models of “inner security” and “person-centered” dementia care, maintaining relationships is a central component (Kitwood, Citation1993b; Panke-Kochinke, Citation2013). Our identified conditions might facilitate or inhibit maintaining a balance of “inner security”. However, notably, the terminology used differs across these studies (e.g. “feeling safe”, “inner security” and “sense of safety”).

The studies identified in our review reported only a few strategies for feeling safe that are performed by people living with dementia. Some strategies are related to avoidance behavior. Situations, places or people that could restrict the feeling of safety are avoided by people living with dementia. This withdrawal behavior is considered particularly problematic (Harris, Citation2006; Zingmark et al., Citation2002). Kitwood and Bredin (Citation1992, p. 284) described this withdrawal as “terminal apathy and despair” caused by the loss of self-esteem and social confidence. Furthermore, maintaining routines helps people living with dementia feel safe (Yatczak, Citation2014). Panke-Kochinke (Citation2016) argues that in the context of coping with disease, maintaining self-performed routines with the support of an accepting partner can have positive effects on “inner security”.

Implications for dementia research and health care

To improve participation and develop a comprehensive concept of emotional safety, it is important in dementia research and health care to consider the perspective of people living with dementia. Nevertheless, other perspectives also offer added value in understanding the complex factors that underlie emotional safety, especially in regard to outer conditions and strategies.

As emotional safety is reported to be a primary need of people living with dementia, it is important to consider this concept in person-centered health care. According to Hansen et al. (Citation2017), the clarification of the concept of psychosocial needs (e.g. feeling safe) and a discussion of who should be responsible for meeting these needs and how these needs can be met, should be areas of focus. In addition, further research and health care should take into account the fact that dementia-related factors have an impact on emotional safety. Based on the described changes in safety needs during the course of the disease, personal factors and inner and outer conditions influencing emotional safety, we agree that a dementia-specific view of emotional safety is needed.

In developing patient-centered practices that focus on the needs of people living with dementia, critical attention should be paid to self-reported strategies as well as the strategies used by others. Strengthening the feeling of safety seems to help people living with dementia build relationships and perceive support positively. In this way, it may be possible to improve the care situation for both people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Limitations

A comprehensive search was conducted using multiple databases to provide an interdisciplinary approach and to present a broad spectrum of the specialist literature. By limiting the search period, current available knowledge was predominantly identified and analyzed. However, there is a risk that some relevant publications were not included due to the publication date restrictions.

An inductive approach was a high priority in the data syntheses. However, a working definition of “emotional safety” was used as a deductive starting point and as an orientation to the phenomenon of emotional safety. The identified data seem insufficient for the development of a comprehensive definition. More evidence is needed. A quantitative data synthesis could not be conducted due to the small number of identified quantitative studies. In addition, we observed that emotional safety was not the primary focus of the studies. Therefore, it is conceivable that studies that do not explicitly mention emotional safety in the title or abstract but do include these components in the results were not identified. However, due to our additional approaches to expanding sensitivity, the risk of missed studies seems to be low.

Conclusion

People living with dementia appear to be particularly vulnerable to decreased emotional safety, indicating the need to strengthen their emotional safety in everyday life. Emotional safety is a primary psychological need of people living with dementia and is influenced by disease-related, biographical, demographic and socioeconomic factors. In addition, inner and outer conditions, strategies as well as specific health outcomes seem to be associated with emotional safety. It can be assumed that inner and outer conditions are involved in the creation of a suitable environment for different strategies to enhance emotional safety. Due to the small number of studies, recommendations for practice have been carefully deduced.

In practice, critical attention should be paid to the need for, the conditions surrounding and the (self-reported) strategies used to achieve emotional safety in the context of dementia. Theories and models that frame emotional safety can provide a helpful orientation in health care and research. Further research should focus on obtaining a comprehensive picture of the emotional safety needs of people living with dementia to enable person-centered strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Gabriela Wolpers and Ms. Anika Hagedorn (Caritasverband für den Kreis Mettmann e.V., Germany) for the common content exchange.

The review protocol has been registered at PROSPERO (CRD42018082697).

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. SJ is affiliated with the funding organization “Stiftung Wohlfahrtspflege NRW”.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bakkalbasi, N., Bauer, K., Glover, J., & Wang, L. (2006). Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomedical Digital Libraries, 3(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-5581-3-7

- Bossen, A. L., Specht, J. K. P., & McKenzie, S. E. (2009). Needs of people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: Reviewing the evidence. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 35(3), 8–15.

- Brataas, H. V., Bjugan, H., Wille, T., & Hellzen, O. (2010). Experiences of day care and collaboration among people with mild dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(19–20), 2839–2848. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03270.x

- Brittain, K., Corner, L., Robinson, L., & Bond, J. (2010). Ageing in place and technologies of place: The lived experience of people with dementia in changing social, physical and technological environments. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32(2), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01203.x

- Brorsson, A., Öhman, A., Cutchin, M., & Nygård, L. (2013). Managing critical incidents in grocery shopping by community-living people with Alzheimer’s disease. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(4), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2012.752031

- Brorsson, A., Öhman, A., Lundberg, S., & Nygård, L. (2011). Accessibility in public space as perceived by people with Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 10(4), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211415314

- Clare, L., Rowlands, J., Bruce, E., Surr, C., & Downs, M. (2008). The experience of living with dementia in residential care: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Gerontologist, 48(6), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/48.6.711

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1991). A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 5(3), 155–174.

- Cronfalk, B. S., Norberg, A., & Ternestedt, B.-M. (2017). They are still the same – Family members’ stories about their relatives with dementia disorders as residents in a nursing home. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(1), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12442

- Duggan, S., Blackman, T., Martyr, A., & van Schaik, P. (2008). The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A ‘shrinking world’? Dementia, 7(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208091158

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ericsson, I., Kjellström, S., & Hellström, I. (2013). Creating relationships with persons with moderate to severe dementia. Dementia, 12(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211418161

- Faith, M. (2014). A phenomenological investigation of the online blogs of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/9eac5f5af9cebe8db5644ffa8261d7b1/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Farina, N., Page, T. E., Daley, S., Brown, A., Bowling, A., Basset, T., … Banerjee, S. (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 13(5), 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010

- Fazio, S., Pace, D., Flinner, J., & Kallmyer, B. (2018). The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(Suppl. 1), S10–S19. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx122

- Genoe, M. R. (2009). Living with hope in the midst of change: The meaning of leisure within the context of dementia. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10012/4500

- Genoe, M. R., & Dupuis, S. L. (2011). “I’m just like I always was”: A phenomenological exploration of leisure, identity and dementia. Leisure/Loisir, 35(4), 423–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.649111

- Groenewoud, H., Lange, J., Schikhof, Y., Astell, A., Joddrell, P., & Goumans, M. (2017). People with dementia playing casual games on a tablet. Gerontechnology, 16(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2017.16.1.004.00

- Grøndahl, V. A., Persenius, M., Bååth, C., & Helgesen, A. K. (2017). The use of life stories and its influence on persons with dementia, their relatives and staff – A systematic mixed studies review. BioMed Central Nursing, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0223-5

- Hadjri, K., Rooney, C., & Faith, V. (2015). Housing choices and care home design for people with dementia. Herd: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 8(3), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715573740

- Hannes, K. (2011). Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In J. Noyes, A. Booth, K. Hannes, A. Harden, J. Harris, S. Lewin, & C. Lockwood (Eds.), Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Version 1 (updated August 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group. Retrieved from http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance

- Hansen, A., Hauge, S., & Bergland, Å. (2017). Meeting psychosocial needs for persons with dementia in home care services – A qualitative study of different perceptions and practices among health care providers. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0612-3

- Harris, P. B. (2006). The experience of living alone with early stage Alzheimer’s disease: What are the person’s concerns? Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 7(2), 84–94.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Bujold, M., & Wassef, M. (2017). Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2

- Hung, L., Phinney, A., Chaudhury, H., Rodney, P., Tabamo, J., & Bohl, D. (2017). “Little things matter!” Exploring the perspectives of patients with dementia about the hospital environment. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 12(3), e12153. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12153

- Hynninen, N., Saarnio, R., & Isola, A. (2015). Treatment of older people with dementia in surgical wards from the viewpoints of the patients and close relatives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(23–24), 3691–3699. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13004

- Karlsson, E., Axelsson, K., Zingmark, K., & Sävenstedt, S. (2011). The challenge of coming to terms with the use of a new digital assistive device: A case study of two persons with mild dementia. The Open Nursing Journal, 5(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.2174/18744346011050100102

- Kitwood, T. (1993a). Person and process in dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 8(7), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.930080702

- Kitwood, T. (1993b). Towards a theory of dementia care: The interpersonal process. Ageing and Society, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00000647

- Kitwood, T. (1997). The experience of dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 1(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607869757344

- Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society, 12(3), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x0000502x

- Lang, A., Edwards, N., & Fleiszer, A. (2008). Safety in home care: A broadened perspective of patient safety. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 20(2), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm068

- Lawrence, V., Samsi, K., Murray, J., Harari, D., & Banerjee, S. (2011). Dying well with dementia: Qualitative examination of end-of-life care. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(5), 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093989

- Manera, V., Chapoulie, E., Bourgeois, J., Guerchouche, R., David, R., Ondrej, J., Drettakis, G., & Robert, P. (2016). A feasibility study with image-based rendered virtual reality in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. PLoS One, 11(3), e0151487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151487

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- Mazaheri, M., Eriksson, L. E., Nasrabadi, A. N., Sunvisson, H., & Heikkilä, K. (2014). Experiences of dementia in a foreign country: Qualitative content analysis of interviews with people with dementia. BioMed Central Public Health, 14, 794.

- Mjørud, M., Engedal, K., Røsvik, J., & Kirkevold, M. (2017). Living with dementia in a nursing home, as described by persons with dementia: A phenomenological hermeneutic study. BioMed Central Health Services Research, 17(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2053-2

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012). Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (3rd ed.). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Nijhof, N., van Gemert-Pijnen, L. J., Woolrych, R., & Sixsmith, A. (2013). An evaluation of preventive sensor technology for dementia care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 19(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2012.120605

- Osborne, H., Stokes, G., & Simpson, J. (2010). A psychosocial model of parent fixation in people with dementia: The role of personality and attachment. Aging & Mental Health, 14(8), 928–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.501055

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

- Panke-Kochinke, B. (2013). Eine Analyse der individuellen Wahrnehmungs- und Bewältigungsstrategien von Menschen mit Demenz im Frühstadium ihrer Erkrankung unter Beachtung der Funktion und Wirksamkeit von Selbsthilfegruppen auf der Grundlage von Selbstäußerungen [An analysis of the individual perception and coping strategies of people with dementia in the early stage of their disease in accordance to the function and effectiveness of self-help groups on the basis of self-expression]. Pflege, 26(6), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1024/1012-5302/a000327

- Panke-Kochinke, B. (2014). Menschen mit Demenz in Selbsthilfegruppen: Krankheitsbewältigung im Vergleich zu Menschen mit Multipler Sklerose. Beltz Juventa.

- Panke-Kochinke, B. (2016). Leben mit Demenz, Multipler Sklerose und Parkinson: Muster der Anpassung und Bewältigung im Lebensablauf. Beltz Juventa.

- Perrar, K. M., Schmidt, H., Eisenmann, Y., Cremer, B., & Voltz, R. (2015). Needs of people with severe dementia at the end-of-life: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 43(2), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-140435

- Scholl, I., Zill, J. M., Härter, M., & Dirmaier, J. (2014). An integrative model of patient-centeredness – A systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One, 9(9), e107828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107828

- Sørensen, L., Waldorff, F., & Waldemar, G. (2008). Coping with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 7(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208093285

- Steeman, E., Dierckx de Casterlé, B., Godderis, J., & Grypdonck, M. (2006). Living with early-stage dementia: A review of qualitative studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 54(6), 722–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03874.x

- Vincent, S. M. (1995). Emotional safety in adventure therapy programs: Can it be defined? Journal of Experiential Education, 18(2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382599501800204

- von Kutzleben, M., Schmid, W., Halek, M., Holle, B., & Bartholomeyczik, S. (2012). Community-dwelling persons with dementia: What do they need? What do they demand? What do they do? A systematic review on the subjective experiences of persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 16(3), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.614594

- Wang, J.-J., Feldt, K., & Cheng, W.-Y. (2012). Characteristics and underlying meaning of hoarding behavior in elders with Alzheimer’s dementia: Caregivers’ perspective. Journal of Nursing Research, 20(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182656132

- Wang, C.-J., Pai, M.-C., Hsiao, H.-S., & Wang, J.-J. (2015). The investigation and comparison of the underlying needs of common disruptive behaviours in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29(4), 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12208

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- World Health Organization. (2012). Dementia: A public health priority. World Health Organization Press.

- Yatczak, J. M. (2014). An exploration of the use of objects in the creation, maintenance, and social performance of self among people with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders [Doctoral dissertation]. Wayne State University.

- Zingmark, K., Sandman, P. O., & Norberg, A. (2002). Promoting a good life among people with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 38(1), 50–58.

Appendix A

1. Search strategy for MEDLINE (via PubMed)

Research period: 01 November 2007 to 31 October 2017

Date of research: 02 November 2017

2. Search strategy “security” for MEDLINE (via PubMed)

Research period: 01 November 2007–31 October 2017

Date of research: 26 January 2018

3. Search strategy for EMBASE (via Scopus)

Research period: 2007–2017

Date of research: 02 November 2017

4. Search strategy “security” for EMBASE (via Scopus)

Research period: 2007–2017

Date of research: 26 January 2018

5. Search strategy for CINAHL Plus (via EBSCOhost)

Research period: 01 November 2007–31 October 2017

Date of research: 02 November 2017

6. Search strategy “security” for CINAHL Plus (via EBSCOhost)

Research period: 01 November 2007–31 October 2017

Date of research: 26 January 2018

7. Search strategy for PsycINFO & PSYNDEX (via EBSCOhost)

Research period: November 2007 to October 2017

Date of research: 02 November 2017

8. Search strategy “security” for PsycINFO & PSYNDEX (via EBSCOhost)

Research period: November 2007 to October 2017

Date of research: 26 January 2018

9. Search strategy for the Cochrane Library

Research period: November 2007 to October 2017

Date of research: 2 November 2017

10. Search strategy “security” for the Cochrane Library

Research period: November 2007 to October 2017

Date of research: 26 January 2018

11. Search strategy for Journals@Ovid (via Ovid)

Research period: Entry date last 10 years

Date of research: 2 November 2017

12. Search strategy “security” for Journals@Ovid (via Ovid)

Research period: Entry date last 10 years

Date of research: 26 January 2018

Appendix B

Combinations of the five core components of the search terms