Abstract

Background

Exercise protects against somatic comorbidities and positively affects cognitive function and psychiatric symptoms in patients with severe mental illness. In forensic psychiatry, exercise is a novel concept. Staff at inpatient care facilities may be important resources for successful intervention. Little is known about staff’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise in forensic psychiatric care.

Aims

To translate, culturally adapt and test the feasibility of the Exercise in Mental Health Questionnaire-Health Professionals Version (EMIQ-HP) in the Swedish context, and to use this EMIQ-HP-Swedish version to describe staff’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise.

Method

The EMIQ-HP was translated, culturally adapted, pilot-tested and thereafter used in a cross-sectional nationwide survey.

Results

Ten of 25 clinics and 239 health professionals (50.1%) participated. Two parts of the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version showed problems. Most participants considered exercise to be a low-risk treatment (92.4%) that is beneficial (99.2%). Training in exercise prescription was reported by 16.3%. Half of participants (52.7%) prescribed exercise and 50.0% of those undertook formal assessments prior to prescribing.

Conclusions

Creation of the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version was successful, despite some clarity problems. Exercise appears to be prescribed informally by non-experts in Swedish forensic psychiatric care and does not address treatment goals.

Introduction

Patients with severe mental illness are at increased risk to suffer from somatic disorders, such as cardiovascular disorders (Correll et al., Citation2017), diabetes (Vancampfort, Correll, et al., Citation2016) and metabolic syndrome (Vancampfort et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the life expectancy of patients with severe mental illness is shorter than in the general population (Correll et al., Citation2017; Laursen et al., Citation2012). In the general population, exercise protects against these somatic disorders (Perez et al., Citation2019; Yusuf et al., Citation2004; Zanuso et al., Citation2017). Patients with severe mental illness are less physically active (Stubbs et al., Citation2016; Vancampfort, Firth, et al., Citation2017) and have a lower cardiorespiratory fitness (Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2017) compared to the general population. Exercise also has positive effects on psychiatric symptoms in patients with depression (Schuch et al., Citation2016) and anxiety (Stubbs et al., Citation2017). In patients with schizophrenia, exercise has shown to have positive effects on psychiatric symptoms as well as on cognitive function (Dauwan et al., Citation2016; Firth et al., Citation2017; Stubbs et al., Citation2018). The need to increase the use of exercise in care of patients with severe mental illness has therefore been proposed (Stubbs et al., Citation2018).

Reasons for lower physical activity levels among patients with severe mental illness are likely multi-dimensional, including the presence of psychiatric symptoms as well as physical and psychological states, social and environmental factors (Firth et al., Citation2016; Stubbs et al., Citation2017). Low participation, low compliance and high dropout from interventions, also make research in the field a difficult endeavor (Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2016). Strategies to improve exercise participation have been proposed, such as individually tailored interventions prescribed by exercise experts (Stubbs et al., Citation2018; Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2016, Citation2017), the presence of a training partner, informational support, available and affordable exercise facilities and/or emotional support (Firth et al., Citation2016; Soundy et al., Citation2014).

Forensic psychiatric care differs from general psychiatric care in some aspects. There are no specific forensic psychiatric diagnoses, most patients have psychotic disorders but comorbidity, such as substance abuse, personality disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders are more common compared to general psychiatry (Degl’ Innocenti et al., Citation2014; Palijan et al., Citation2009). Pharmacological treatment differs to general psychiatry in Sweden, patients in forensic psychiatry are more often treated with traditional antipsychotics and combinations of several psychoactive pharmaceuticals are more common (SBU, Citation2018). Furthermore, in forensic psychiatry the patients are criminal offenders, often of violent crime, in addition to being patients (Svennerlind et al., Citation2010), meaning the group is medico-legally defined as opposed to strictly medically. Of possible significance to exercise and other rehabilitative interventions, all patients in forensic psychiatric care are involuntary admitted and duration of treatment as inpatients is considerable and often extends over several years with a median stay in Sweden of 2.6 years (Andreasson et al., Citation2014). As in patients in general psychiatry, poor fitness levels have been reported in patients in forensic psychiatric care (Bergman et al., Citation2020).

The evidence base for rehabilitative interventions in forensic psychiatric care is weak (Vollm et al., Citation2018) and the importance of developing evidence-based treatment and rehabilitation for patients in forensic psychiatric care have recently been emphasized (Howner et al., Citation2018). That exercise can be regarded as a promising intervention in forensic psychiatric care has been proposed (Andiné & Bergman, Citation2019), based on its positive effects in several areas important for patients with severe mental illness, such as cognitive function (Firth et al., Citation2017), physical performance (Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2017), somatic disorders (Cormie et al., Citation2017; Perez et al., Citation2019; Yusuf et al., Citation2004; Zanuso et al., Citation2017) and psychiatric symptoms (Dauwan et al., Citation2016; Schuch et al., Citation2016; Stubbs et al., Citation2017). However, research on exercise in forensic psychiatric care is scarce.

To further develop exercise as an intervention in forensic psychiatric care, it has been proposed that healthcare staff are an important resource (Farholm et al., Citation2017; Fie et al., Citation2013). To investigate staff’s knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding exercise, Stanton and colleagues developed the Exercise in Mental Illness Questionnaire-Health Professionals Version (EMIQ-HP) (Stanton et al., Citation2014). The EMIQ-HP is a survey consisting of 68 single questions, divided into six parts: 1: exercise knowledge, 2: exercise beliefs, 3: exercise prescription behaviours, 4: barriers to exercise prescription and exercise participation, 5: own exercise habits, and 6: demographics.

The aim of the present study was to translate, culturally adapt and test the feasibility of the EMIQ-HP in the Swedish context. A further aim was to use the questionnaire to investigate staff’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding exercise in forensic psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden.

Materials and methods

Translation, cultural adaptation and feasibility of the EMIQ-HP

Permission to translate the EMIQ-HP was obtained from the original author. The original English version of the EMIQ-HP was translated into Swedish by a native Swedish-speaking professional translator who was also a registered nurse by profession, resulting in a preliminary Swedish version. Part 5 of EMIQ-HP consists of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The IPAQ has already been translated and validated to Swedish conditions, and this version was downloaded on 16 October 2017 from the IPAQ website (https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/questionnaire_links) and not included in the translation/cultural adaptation process.

The preliminary Swedish version of the EMIQ-HP was discussed within an expert group. The expert group consisted of six persons with extensive clinical experience, of which five had more than 20 years of clinical experience, either as a physiotherapist, psychiatrist or psychologist. In addition, they were also academics (one professor, four associated professors and one PhD student) with extensive publications in the fields of psychology, forensic psychiatry, exercise, physiotherapy and rehabilitation. Of the included experts, several had previous experience in development, translation, cultural adaptation and validation of questionnaires. The EMIQ-HP does not measure any operationalized construct or concept. Hence, it was viewed as a survey rather than a test or a score. As such, the questionnaire’s feasibility was tested for its clarity, relevance, representativeness and difficulty of each item within the context of the part of the questionnaire (Stanton et al., Citation2014). When agreement was reached within the expert group for the entire questionnaire, a native English-speaking professional translator, specialized in translations within life science/medicine, back-translated this updated version of the questionnaire into English. The back-translator was not familiar with the original English version of the EMIQ-HP. Back-translation raised additional questions that were discussed within the expert group and adjustments to the Swedish version were made until agreement was reached, resulting in a pilot version.

Ten health professionals were recruited to a pilot study. All included participants were employed at a forensic psychiatric clinic with inpatient care and recruited based on personal knowledge to represent different health professions. The participants had different occupations such as nurses (n = 3), health workers (n = 2), psychologists (n = 2), occupational therapists (n = 1) and physicians (n = 2). The participants of the pilot study completed the questionnaire with one researcher (HB) present. Interviews with the participants were conducted freely according to Beatty and Willis (Citation2007), to assess whether the questions were phrased so that they generated the intended information. If problematic phrasings were identified, participants were encouraged to suggest better alternatives. The suggestions made by the participants were discussed within the expert group along with problems identified by HB. Final adjustments were made, resulting in the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version.

Health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise for patients with a mental illness, in forensic psychiatric inpatient care

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version. Data collection took place between 1 September 2018 and 31 January 2019. All 25 forensic psychiatric clinics with inpatient care facilities within the national public health system in Sweden were invited to participate. In case of a positive answer, a local collaborator at each clinic was engaged as contact person for administration of the questionnaires. The following occupations were included: health worker, nurse, occupational therapist, physician, physiotherapist, psychologist and social worker. In addition, staff with designated responsibility for exercise were included. The decision to include these professions were based on either having formal right to prescribe exercise within the Swedish healthcare system, or to otherwise take part in treatment planning. The EMIQ-HP, Swedish version was emailed as a pdf-file together with written information about the study and an informed consent form to the local collaborator at each clinic. The collaborator printed out the documents and administered them to the included health professionals via internal mail. The completed questionnaires and informed consent forms were collected by the collaborator and returned to the researchers via mail. The study was approved by the regional research ethics committee in Gothenburg, Sweden (Ref. 242-26).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to report respondent demographics and answers regarding knowledge, attitudes and behaviors. Between-groups comparisons were made using Fischer’s exact test. Absolute proportions were reported for 2 × 2 tables. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare non-normally distributed, continuous variables between groups, with Eta-squared as a measure of effect size. To perform comparisons between different health professions, health workers and physiotherapists, (i.e. the two professions with exercise as their main responsibility), were collapsed into one group as exercise experts and compared to all the other professions, collapsed into another group. IPAQ data was processed to address obvious errors according to guidelines accessed on 1 March 2019 from the IPAQ website (https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 22).

Results

Translation, cultural adaptation and feasibility of the EMIQ-HP

Some cultural adaptations were made for the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version. Questions about academic degrees and healthcare disciplines were culturally adapted and questions concerning marital status, ethnic background and information about citizenship/migration were omitted.

Some clarity issues of part 2, covering exercise beliefs, emerged during the pilot testing. The participants are asked to rate how valuable they believe exercise is for patients with mental illness, compared to other interventions. Several participants in the pilot group raised objections against this part, since they believed it seemed inappropriate to rate different interventions against each other and that one intervention may be necessary for successful use of another. Therefore, the possibility to answer Q11a–h with ‘have no opinion’ was added. Also, Q37–48 of part 4, covering degree of agreement to statements from patients about barriers to exercise participation, was considered to be ambiguous. Contact was taken with the original author of the instrument and further clarifications were made. After agreeing upon revisions considering input from the pilot study, a final Swedish version was established.

Health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise for patients with a mental illness, in forensic psychiatric inpatient care

Ten out of 25 forensic psychiatric clinics agreed to participate in the study. In total, 477 questionnaires were administered and 239 professionals completed the survey (50.1%) (). Only participants who answered Q1 with ‘yes’ were instructed to answer Q2–4. Participants who answered Q19 with ‘Never’ were instructed to skip Q20–25. In addition, there are some internal missing data. The participating forensic psychiatric clinics differed in size, hence the number of available health professionals meeting the inclusion criteria at each clinic ranged between 16 and 98. Local participation rates varied between 15.7% and 82.9%.

Table 1. Demographic description and physical activity levels of health professionals in forensic psychiatric care.

shows the participating staff’s knowledge and behaviors regarding exercise. Of the 39 participants (16.3%) who stated that they had completed formal training in exercise prescription, 22 participants (9 nurses, 6 physicians, 4 physiotherapists, 2 health workers and 1 occupational therapist) referred to their primary professional education when asked to specify the formal training (Q2). Thirteen participants referred to different minor courses. Two participants referred to academic exams in the field of health or sports, and 5 participants did not specify. A few participants referred to more than one of the above,

Table 2. Knowledge (Q1–4) and behaviors (Q19–25) regarding exercise for patients with a mental illness of health professionals in forensic psychiatric care.

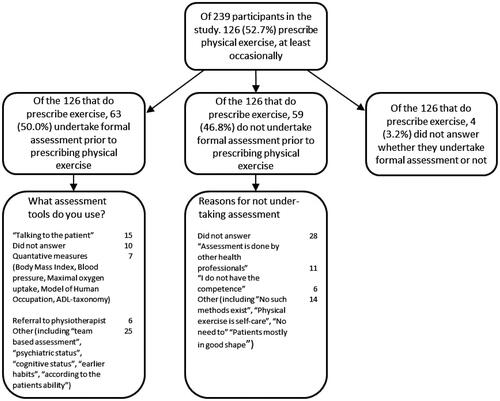

For prescription behaviors of participants that do prescribe exercise, at least occasionally, see .

Figure 1. Prescription behaviors of the 126 health professionals in forensic psychiatric care, that stated that they do prescribe exercise, at least occasionally.

No significant associations were found (Kruskal Wallis H test: X2 = 3.203, df = 3, p = 0.361, Eta2 = 0.014) between the participants’ own physical activity level and whether they prescribed exercise to patients with mental illness. The practice of prescribing exercise differed significantly between the 8 included professions (Fischer’s exact test: df = 7, p = 0.002). When exercise experts (health workers and physiotherapists) were compared to a group composed of all other health professionals (nurses, occupational therapists, physicians, psychologists, social workers and ‘others’), it was found that the former group prescribed exercise, at least occasionally, significantly more often than the latter group (10/10 vs. 114/222, Fischer’s exact test: df = 1, p = 0.002). Also, the habit of suggesting weight or resistance training (Fischer’s exact test: df = 7, p = 0.006) and team sports (Fischer’s exact test: df = 7, p = 0.001) differed significantly between all eight professions. It was revealed that the group of health workers and physiotherapists prescribed weight training (9/10 vs. 28/110, Fischer’s exact test: df = 1, p < 0.001) and team sports (8/10 vs. 27/110, Fischer’s exact test: df = 1, p = 0.001) significantly more than the group of all other health professionals. There were no significant differences between health professionals regarding prescription of other exercise modalities, (aerobic exercise, swimming, combat sports, relaxation activities).

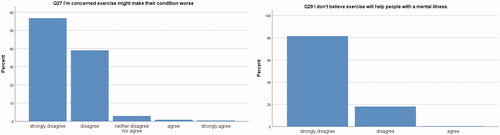

Exercise was viewed as a safe activity with positive health effects for patients by the participants staff (). Further results to Q26–36, regarding barriers to exercise prescription, are presented in . Few participants agreed to the proposed barriers. The answers to Q35 concerning lack of knowledge on exercise prescription and Q34 and Q36, concerning whose duty it is to prescribe exercise, seemed to be more evenly distributed across the Likert scale.

Figure 2. Levels of agreement to statements Q27 ‘I’m concerned exercise might make their condition worse’ and Q29 ‘I don’t believe exercise will help people with a mental illness’, by health professionals in forensic psychiatric care (n = 238).

Table 3. Levels of agreement by health professionals regarding barriers to exercise prescription (Q26–36) for patients with a mental illness in forensic psychiatric care.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were that the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version was useful and provided new insights about Swedish health professional’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise for patients with mental illness in forensic psychiatric care, but two of its six parts showed ambiguity. Results indicate that while exercise is viewed as a safe activity with positive health effects for patients, it seems to be used in an informal manner and to be prescribed to a large extent by non-experts

Translation, cultural adaptation and feasibility of the EMIQ-HP

Part 2 of the questionnaire assesses health professionals’ beliefs about physical exercise, including rating the value of exercise compared to other treatment interventions. This was problematic to the health professionals included in the pilot study because value of different interventions may vary over time for the same patient, between patients and/or depending on diagnosis and/or symptom severity. Also, one intervention may serve as a prerequisite for the successful use of another. These problems were addressed by adding the possibility of answering ‘no opinion’ to Q11a–11h. This adaptation may not have been sufficient, as confirmed by handwritten remarks in the completed questionnaires by some participants. The problems with part 2 were extensive and results from part 2 were therefore omitted. The fact that the EMIQ-HP does not take type of mental illness, symptom severity or symptom duration into account, has previously been pointed out as a potential shortcoming (Stanton et al., Citation2018). The results from the present study is in agreement with this.

The questions in part 4 about barriers to exercise participation also presented problems. Pilot testing showed that statements could be perceived and interpreted in different ways. Adaptations were made after contact with the author of the original English version. Still, handwritten remarks by some participants raise concerns about the clarity of this part, resulting in omission of Q37–48 from analysis.

Despite the aforementioned issues, the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version was found to be feasible to survey knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise in the intended group of health professionals.

Health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise for patients with a mental illness, in forensic psychiatric inpatient care

The general attitude to physical exercise was positive among the participants. The participants seemed to look upon exercise as being a helpful intervention, with low risk. To confirm this, as many as 95.4% of the participants disagreed with the statement ‘I’m concerned exercise might make their condition worse’ (Q27) and close to 100% disagreed with, ‘I don’t believe exercise will help people with a mental illness’ (Q29). Overall, few participants agreed with the stated barriers to prescribe exercise (Q26–36), with the possible exception of statements about whether exercise prescribing really is a part of their professional role or preferably should be done by an exercise expert (Q34–36). The equally-distributed answers to these questions might reflect that there is no consensus on exercise prescription or on the need for exercise expertise in forensic psychiatric care.

Out of the 239 participants, 39 (16.3%) stated that they had undergone formal training in exercise prescription. When asked to provide details about this formal training, the picture was diverse. A few physicians and nurses referred to their vocational training. While some participants referred to several years of university education and training as a health worker or a physiotherapist, other participants mentioned minor courses as examples of formal training, such as single day in-service training and personal trainer-courses. The heterogeneous formal training of these 39 participants raises questions about what kind of training should be required in order to be able to prescribe exercise in forensic psychiatric care. That expertise in exercise is of importance to patient adherence as well as to outcome of exercise interventions in patients with severe mental illness has been reported previously (Stubbs et al., Citation2018; Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2016).

The results of the present study did not find any association with health professionals’ own exercise habits which is in accordance with a previous study of nurses in inpatient mental health settings (Stanton et al., Citation2015) but opposite to findings of others (Fie et al., Citation2013). However, prescription behaviors were observed to differ between different occupations. As expected, significantly more exercise experts prescribed exercise compared to other health professions. Virtually all (9 out of 10) of the participating exercise experts prescribed weight or resistance training compared to less than 30% of any other occupational category. This is of interest, since reduced leg strength has, been reported to be a predictor for reduced walking capacity in patients with schizophrenia (Vancampfort et al., Citation2013). It is reasonable to argue that exercise should be prescribed in order to reach the patients’ rehabilitation goals, rather than be dependent on the occupation of the prescriber. Since only five health workers and five physiotherapists answered the present survey, and three of the health workers and three of the physiotherapists were employed at the same clinic, it seems questionable whether patients have equal access to exercise experts in all clinics that participated in this study, implying that patients in forensic psychiatric care do not receive equal care. Equal care in this respect should be possible to achieve, especially since all forensic psychiatric hospitals in Sweden are part of the same national public health system.

Despite that few (16.3%) of the participants have stated that they have had undergone formal training in exercise prescription, exercise was indeed prescribed, at least occasionally, by more than half of the participants. Half of them, in turn, undertook a formal assessment before prescribing exercise. The examples of assessments named by the participants are to a large degree informal and few are quantitative. As indicated by the wide array of assessment tools used by the participants as well as diverse reasons for not undertaking any assessment, it is reasonable to believe that there is no common understanding about which health professional should perform the assessment, what to assess, or which assessment tool to use.

The few examples of quantitative assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness found in the present study, raises concerns. Low cardiorespiratory fitness is common in severe mental illness (Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2017) and in forensic psychiatric care (Bergman et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disorder (Ladenvall et al., Citation2016), which is common in severe mental illness (Laursen et al., Citation2012). It should be possible to target low cardiorespiratory fitness with exercise interventions within the context of forensic psychiatric care, as has been proposed in care for patients with severe mental illness in the general population (Stubbs et al., Citation2018). However, absence of assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness in the present study indicates that this is rarely done. Furthermore, there are no examples of formal assessments of psychiatric symptoms or cognitive deficits prior to an exercise intervention, indicating that exercise is not often used to address these symptoms and deficits. The use of exercise to treat psychiatric symptoms and cognitive deficits in severe mental illness is still a relatively novel concept, but the evidence base has grown stronger in recent years (Dauwan et al., Citation2016; Firth et al., Citation2017; Stubbs et al., Citation2018). Almost half (48.4%) of the exercise-prescribing participants in this study stated that they did not undertake any formal assessment. Reasons given included that such assessments are done by others and that participants did not have sufficient competence to perform such assessments. Almost half of the exercise-prescribing participants who did not undertake an assessment, gave no reason for this, making definitive conclusions difficult, but strengthens the overall impression that exercise seems to be used in informal, non-specific manners, and seldom to address treatment goals in forensic psychiatric care, such as to reduce psychiatric symptoms (Dauwan et al., Citation2016; Stubbs et al., Citation2018) or cognitive deficits (Firth et al., Citation2017). Additionally, exercise does not seem to be used to address poor physical state (Bergman et al., Citation2020; Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2017). This is in contrast to the plethora of disorders and conditions, known to be treatable with exercise interventions, found in patients with severe mental illness (Firth et al., Citation2017; Vancampfort et al., Citation2015, Vancampfort, Correll, et al., Citation2016; Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2017) and in forensic psychiatry (Bergman et al., Citation2020; Degl’ Innocenti et al., Citation2014). There are indeed existing reliable methods of assessment of physical performance available that have been reported to be both reliable for patients with severe mental illness (Vancampfort et al., Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2014) and feasible in a forensic psychiatric context (Bergman et al., Citation2020).

In light of the results of the present study as well as based on research on the positive effects of exercise for patients with severe mental illness in general, we would like to propose:

An increased formal use of exercise in forensic psychiatric care, individually adapted to the patients’ needs, as has been proposed to address poor physical performance (Stubbs et al., Citation2018), psychiatric symptoms (Schuch et al., Citation2016; Stubbs et al., Citation2017) and cognitive deficits (Dauwan et al., Citation2016; Firth et al., Citation2017; Stubbs et al., Citation2018) as well as to protect against somatic co-morbidities (Cormie et al., Citation2017; Yusuf et al., Citation2004; Zanuso et al., Citation2017).

An increased use of exercise experts, such as physiotherapists or possibly health workers, in forensic psychiatric care in order to increase the use of formal assessments, to achieve better individual adaptation of exercise interventions to individual treatment goals, to improve adherence to exercise interventions (Vancampfort, Rosenbaum, et al., Citation2016) and to improve outcomes of such interventions (Stubbs et al., Citation2018).

Strength and limitations

The present study is to our knowledge the largest survey on knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding exercise for people with mental illness among health professionals, and the first in forensic psychiatry. A survey study makes it possible to collect data from a vast number of participants, and also enables the possibility of replicating the study to follow change over time.

Of the 25 forensic psychiatric clinics that exist throughout Sweden, ten clinics chose to participate, and selection bias cannot be ruled out. However, the ten participating clinics were geographically separated and ranged in size from very small to some of the largest clinics in the country. Local answering rates differed (15.7–82.9%) among the participating clinics. The highest values came from some of the smallest clinics, which might reflect easier communication internally between the local study collaborator and the included health professionals. Moreover, it is possible that health professionals who are already interested in exercise, more frequently answered the questionnaire.

In conclusion, the EMIQ-HP-Swedish version can be used to investigate knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among health professionals regarding exercise. Part 2 (knowledge) as well as part 4 (barriers to exercise participation) were found to be unclear and difficult to answer, and were therefor omitted from the analysis.

Exercise was regarded as an intervention with positive effects and low risk by health professionals within forensic psychiatric care in Sweden. However, exercise seemed to be used in an informal, non-specific manner, prescribed by non-experts, and did not seem to be used to address defined treatment goals. An increased use of exercise to reach specific goals and an increased use of exercise experts are therefore warranted in forensic psychiatric care.

Acknowledgements

Scientific editing was performed by Gothia Forum, Region Västra Götaland, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andiné, P., & Bergman, H. (2019). Focus on brain health to improve care, treatment, and rehabilitation in forensic psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 1–5.

- Andreasson, H., Nyman, M., Krona, H., Meyer, L., Anckarsäter, H., Nilsson, T., & Hofvander, B. (2014). Predictors of length of stay in forensic psychiatry: The influence of perceived risk of violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(6), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.038

- Beatty, P. C., & Willis, G. B. (2007). Research synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(2), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfm006

- Bergman, H., Nilsson, T., Andiné, P., Degl’Innocenti, A., Thomeé, R., & Gutke, A. (2020). Physical performance and physical activity of patients under compulsory forensic psychiatric inpatient care. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 36(4), 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1488320

- Cormie, P., Zopf, E. M., Zhang, X., & Schmitz, K. H. (2017). The impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related adverse effects. Epidemiologic Reviews, 39(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxx007

- Correll, C. U., Solmi, M., Veronese, N., Bortolato, B., Rosson, S., Santonastaso, P., Thapa-Chhetri, N., Fornaro, M., Gallicchio, D., Collantoni, E., Pigato, G., Favaro, A., Monaco, F., Kohler, C., Vancampfort, D., Ward, P. B., Gaughran, F., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2017). Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20420

- Dauwan, M., Begemann, M. J., Heringa, S. M., & Sommer, I. E. (2016). Exercise improves clinical symptoms, quality of life, global functioning, and depression in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(3), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv164

- Degl’ Innocenti, A., Hassing, L. B., Lindqvist, A.-S., Andersson, H., Eriksson, L., Hanson, F. H., Möller, N., Nilsson, T., Hofvander, B., & Anckarsäter, H. (2014). First report from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register (SNFPR). International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(3), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.11.013

- Farholm, A., Sorensen, M., & Halvari, H. (2017). Motivational factors associated with physical activity and quality of life in people with severe mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(4), 914–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12413

- Fie, S., Norman, I. J., & While, A. E. (2013). The relationship between physicians’ and nurses’ personal physical activity habits and their health-promotion practice: A systematic review. Health Education Journal, 72(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896911430763

- Firth, J., Carney, R., Jerome, L., Elliott, R., French, P., & Yung, A. R. (2016). The effects and determinants of exercise participation in first-episode psychosis: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0751-7

- Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Gorczynski, P., Yung, A. R., & Vancampfort, D. (2016). Motivating factors and barriers towards exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2869–2881. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001732

- Firth, J., Stubbs, B., Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Malchow, B., Schuch, F., & Yung, A. R. (2017). Aerobic exercise improves cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(3), 546–556.

- Howner, K., Andiné, P., Bertilsson, G., Hultcrantz, M., Lindström, E., Mowafi, F., Snellman, A., & Hofvander, B. (2018). Mapping systematic reviews on forensic psychiatric care: A systematic review identifying knowledge gaps. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00452

- Ladenvall, P., Persson, C. U., Mandalenakis, Z., Wilhelmsen, L., Grimby, G., Svardsudd, K., & Hansson, P. O. (2016). Low aerobic capacity in middle-aged men associated with increased mortality rates during 45 years of follow-up. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 23(14), 1557–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316655466

- Laursen, T. M., Munk-Olsen, T., & Vestergaard, M. (2012). Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25(2), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca

- Palijan, T. Z., Muzinic, L., & Radeljak, S. (2009). Psychiatric comorbidity in forensic psychiatry. Psychiatria Danubina, 21(3), 429–436.

- Perez, E. A., Gonzalez, M. P., Martinez-Espinosa, R. M., Vila, M. D. M., & Reig Garcia-Galbis, M. (2019). Practical guidance for interventions in adults with metabolic syndrome: Diet and exercise vs. changes in body composition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183481

- Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023

- Soundy, A., Freeman, P., Stubbs, B., Probst, M., & Vancampfort, D. (2014). The value of social support to encourage people with schizophrenia to engage in physical activity: An international insight from specialist mental health physiotherapists. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 23(5), 256–260. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.951481

- Stanton, R., Happell, B., & Reaburn, P. (2014). The development of a questionnaire to investigate the views of health professionals regarding exercise for the treatment of mental illness. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 7(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2014.06.001

- Stanton, R., Happell, B., & Reaburn, P. (2015). Investigating the exercise-prescription practices of nurses working in inpatient mental health settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12125

- Stanton, R., Rosenbaum, S., Lederman, O., & Happell, B. (2018). Implementation in action: How Australian Exercise Physiologists approach exercise prescription for people with mental illness. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1340627

- Stubbs, B., Koyanagi, A., Schuch, F., Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Gaughran, F., … Vancampfort, D. (2017). Physical activity levels and psychosis: A mediation analysis of factors influencing physical activity target achievement among 204 186 people across 46 low- and middle-income countries. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(3), 536–545.

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Hallgren, M., Firth, J., Veronese, N., Solmi, M., Brand, S., Cordes, J., Malchow, B., Gerber, M., Schmitt, A., Correll, C. U., De Hert, M., Gaughran, F., Schneider, F., Kinnafick, F., Falkai, P., Möller, H.-J., & Kahl, K. G. (2018). EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: A meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 54, 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S., Firth, J., Cosco, T., Veronese, N., Salum, G. A., & Schuch, F. B. (2017). An examination of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for people with anxiety and stress-related disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 249, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.020

- Stubbs, B., Williams, J., Gaughran, F., & Craig, T. (2016). How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 171(1-3), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.034

- Svennerlind, C., Nilsson, T., Kerekes, N., Andiné, P., Lagerkvist, M., Forsman, A., Anckarsäter, H., & Malmgren, H. (2010). Mentally disordered criminal offenders in the Swedish criminal system. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 33(4), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.06.003

- Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assassment of Social Services (SBU) (2018). Läkemedelsbehandling inom rättspsykiatrisk vård. En systematisk översikt av medicinska, hälsoekonomiska, sociala och etiska aspekter (Report No 286/2018).

- Vancampfort, D., Correll, C. U., Galling, B., Probst, M., De Hert, M., Ward, P. B., Rosenbaum, S., Gaughran, F., Lally, J., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20309

- Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Schuch, F. B., Rosenbaum, S., Mugisha, J., Hallgren, M., Probst, M., Ward, P. B., Gaughran, F., De Hert, M., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2017). Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20458

- Vancampfort, D., Guelinckx, H., De Hert, M., Stubbs, B., Soundy, A., Rosenbaum, S., De Schepper, E., & Probst, M. (2014). Reliability and clinical correlates of the Astrand-Rhyming sub-maximal exercise test in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 778–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.049

- Vancampfort, D., Probst, M., De Herdt, A., Corredeira, R. M., Carraro, A., De Wachter, D., & De Hert, M. (2013). An impaired health related muscular fitness contributes to a reduced walking capacity in patients with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-5

- Vancampfort, D., Probst, M., Sweers, K., Maurissen, K., Knapen, J., & De Hert, M. (2011). Reliability, minimal detectable changes, practice effects and correlates of the 6-min walk test in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 187(1-2), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.027

- Vancampfort, D., Probst, M., Sweers, K., Maurissen, K., Knapen, J., Willems, J. B., Heip, T., & De Hert, M. (2012). Eurofit test battery in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: Reliability and clinical correlates. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 27(6), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.01.009

- Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S., Schuch, F. B., Ward, P. B., Probst, M., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Prevalence and predictors of treatment dropout from physical activity interventions in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.008

- Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S., Schuch, F., Ward, P. B., Richards, J., Mugisha, J., Probst, M., & Stubbs, B. (2017). Cardiorespiratory fitness in severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(2), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0574-1

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., Mitchell, A. J., De Hert, M., Wampers, M., Ward, P. B., Rosenbaum, S., & Correll, C. U. (2015). Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20252

- Vollm, B. A., Clarke, M., Herrando, V. T., Seppanen, A. O., Gosek, P., Heitzman, J., & Bulten, E. (2018). European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on forensic psychiatry: Evidence based assessment and treatment of mentally disordered offenders. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 51, 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.12.007

- Yusuf, S., Hawken, S., Ôunpuu, S., Dans, T., Avezum, A., Lanas, F., McQueen, M., Budaj, A., Pais, P., Varigos, J., & Lisheng, L. (2004). Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. The Lancet, 364(9438), 937–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9

- Zanuso, S., Sacchetti, M., Sundberg, C. J., Orlando, G., Benvenuti, P., & Balducci, S. (2017). Exercise in type 2 diabetes: genetic, metabolic and neuromuscular adaptations. A review of the evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(21), 1533–1538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096724