Abstract

Background

Internationally there is a shortage of psychiatrists, whilst clinical psychology training is generally oversubscribed. School students interested in psychological health may not be aware of the possibility of studying medicine before specialising in psychiatry. This has implications for the mental health workforce.

Aims

To evaluate the knowledge and attitudes relating to a potential career in psychiatry amongst secondary (high) school students.

Method

A cross-sectional survey evaluated attitudes and knowledge relating to psychiatry and clinical psychology, targeting students from five schools who were studying chemistry, biology and/or psychology at an advanced level.

Results

186 students completed the survey (response rate 41%). Knowledge was generally poor with only 57% of respondents knowing that psychiatrists had medical degrees, and most participants substantially underestimating the salaries of consultant psychiatrists. Attitudinal response patterns were explained by two underlying factors, relating to generally negative attitudes towards psychiatry and positive attitudes towards the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments. Females and those studying psychology reported more positive attitudes towards psychiatry. Those studying chemistry reported more negative attitudes towards the effectiveness of mental health treatment.

Conclusions

Studying psychology predicted positive attitudes towards psychiatry. Such students could be targeted by recruitment campaigns, which emphasise factual information about the specialty.

Introduction

Worldwide, psychiatry generally struggles to recruit sufficient numbers of doctors, leading to staffing levels lagging behind other medical careers. For certain high-income countries, such as Japan and the United States, this is less problematic, though many economically advantaged countries still routinely have around a tenth of senior psychiatric posts vacant at any point (Shields et al., Citation2017). For example, the number of vacant consultant psychiatrist posts across England more than tripled from 220 in 2013 to 708 in 2019. This has resulted in approximately 10% of all consultant psychiatrist roles being unfilled with high levels of vacancies in the other countries of the UK. This rate of unfilled posts was 7.8% in Northern Ireland, 9.6% in Scotland and 12.7% in Wales (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2020a). The shortage of medical qualified staff in mental health services has serious consequences for patient care and safety. For example, patients value continuity of care, which can actually reduce the risk of hospital admission (Ride et al., Citation2019). This continuity can be disrupted by a heavy reliance on locum (temporary) psychiatrists. Moreover, reliance on expensive locum doctors is a major contribution to UK National Health Services (NHS) overspending. For example, one previous Freedom of Information response showed one Mental Health Trust had spent £1.97 M on locum doctors in the year 2014–2015. The current extent of NHS expenditure on locum psychiatrists is not known. However, given that during 2019 there were 285 consultant posts occupied by locums it is still likely to be considerable (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2020a). It is also known that locum doctors are more likely than those employed substantively to receive serious censure for issues in relation to fitness to practise (General Medical Council, Citation2018). Thus, this has implications for patient safety, as well as the quality of care provided.

In order to understand the recruitment challenges in psychiatry, it is vital to capture what others think of the profession. Psychiatry has always been somewhat stigmatised and misunderstood by the public. In one study, half the general public members surveyed were unaware that psychiatrists had medical degrees, 80% underestimated the length of training and there was huge variation in the conditions that they believed were treated by them. The public also believed psychiatrists were most likely to treat patients with counselling, not recognising the major role medication played in care (Williams et al., Citation2001). Most strikingly 47% of public respondents reported they would be uncomfortable sitting next to a psychiatrist at a dinner party. These attitudes are also found in the medical profession; perhaps more shockingly 26% of medical students also agreed that they would not like to be seated next to a psychiatrist at a party (Deb & Lomax, Citation2014)! Likewise, an international survey of medical (non-psychiatric) faculty members reported that 90% of respondents thought that psychiatrists were not good role models for students and 73% thought that psychiatric patients were “emotionally draining” (Stuart et al., Citation2015). Moreover, when medical professionals and non-medics are asked to rank specialities in order of prestige psychiatry is usually listed at, or near, the bottom. These negative attitudes amongst medics may be partly driven by a view that the specialty is relatively “unscientific” and lacks the evidence base that underpins practice in other branches of medicine (Norredam & Album, Citation2007); a viewpoint which is largely no longer valid, especially for the most common, significant mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

The UK Royal College of Psychiatrists has been operating an award-winning recruitment strategy entitled “Choose Psychiatry” (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2020b). This has aimed to reduce the proportion of psychiatric posts that remain vacant (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2017). Their campaigns mainly target medical students and Foundation Years doctors (medical graduates in their first 2 years of postgraduate training), though some interventions have involved running summer schools for those considering applying to medical school. Innovative approaches, such as utilising student psychiatry clerkships, have demonstrated a positive impact on the attitudes of the small number of individuals participating in these interventions (Lyons & Janca, Citation2015). The introduction of early exposure to psychiatry in the undergraduate medical curriculum (Qureshi et al., Citation2016) and increased psychiatric Foundation Years posts (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2015) have also been implemented in the UK in the hope that these will increase recruitment. To date, there have been some early indications of some success with these strategies. Indeed, UK fill rates for 2020 have been reported as 100% for the first year of core training in psychiatry, after one round of readvertising. However, these high rates belie a marked reduction in the absolute numbers of trainees in psychiatry; whilst 418 first-year trainee psychiatrists were recruited in 2020 for that year, the equivalent figure for 2019 was 548 core trainees recruited in the 2019 intake (Health Education England North-West, Citation2020a). It is not clear what has happened to the posts advertised in preceding years, though it is possible that some may have been changed to non-training positions, such as “Trust grade doctor” roles. These relatively low absolute numbers of doctors in core training will have implications for the proportion of more advanced training posts filled; in 2020, only 342 out of 580 (59%) of UK-based places on higher specialist psychiatric training schemes were filled (Health Education England North-West, Citation2020b). In turn, this will have implications for the number of unfilled consultant posts.

There has been much focus on those who have already chosen to be doctors, though little exploration regarding the knowledge and attitudes of those yet to choose their careers. A cross-sectional survey reported that those medical students who go on to choose psychiatry frequently expressed an interest in the area prior to medical school (Farooq et al., Citation2014). Thus there is a strong rationale for understanding the perceptions of psychiatry in those yet to enter university. There is only one published study investigating sixth form students’ attitudes towards psychiatry. This involved asking sixth form students, who had enrolled on a course designed specifically for those interested in medicine, to rate potential careers by likelihood of them entering that career. Psychiatry scored surprisingly high on the ratings by these sixth form students with 12.4% of students reporting that they would “definitely” pursue the career (Maidment et al., Citation2003). Interestingly anaesthetics, dermatology, radiology and ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery all came towards the bottom of the list of desired careers, despite being perceived as more desirable careers amongst doctors. In contrast, a study of first-year medical students at a London university reported only 2.7% of 300 students expressed a desire to pursue psychiatry (Fysh et al., Citation2007). This raises questions about whether those with positive attitudes towards psychiatry actually enter medical school, or whether there is a shift in interests during the early stages of medical education.

Many secondary (high) school students may not even realise that psychiatry is a potential career option for a medicine graduate. Moreover, one profession closely allied with psychiatry, though not facing the same recruitment challenges, is clinical psychology. Indeed, psychology undergraduate and postgraduate courses continue to be oversubscribed; psychology is currently the second most popular degree course in the UK (McGhee, Citation2015). Postgraduate clinical psychology courses, generally leading to careers in mental health services, are likewise grossly oversubscribed and highly competitive. Thus, it is possible that some individuals destined to be clinical psychologists may consider medicine, if they understood more about psychiatry. Indeed, advanced qualification requirements for both psychology and medical courses may be similar, with an emphasis on the sciences (The Medic Portal, Citation2019).

Interventions targeting sixth formers have begun, with psychiatrists providing talks for students. However, in order to ensure the effectiveness of any intervention one must first understand what the students already know and think about the profession. Recruitment strategies could then be tailored accordingly. Thus, this project aimed to assess the knowledge of, and attitudes towards psychiatry as a potential career.

Methods

Ethical approval was granted by the Hull York Medical School (HYMS) Research Ethics Committee. The study employed a cross-sectional survey design, deployed online. The survey questionnaire consisted of a section asking for basic demographic details (age, gender, ethnicity and A-level subjects being studied) and a modified version of the Attitudes to Psychiatry (ATP) questionnaire (Burra et al., Citation1982). In addition, a number of bespoke items were included that were designed to capture the level of factual knowledge about psychiatry and clinical psychology in the respondent. The response format of these latter items varied, according to what seemed most suited to the question. For example, when asking the respondent to estimate the salary of a consultant psychiatrist a pointer had to be moved to the estimated monetary amount. Respondents were instructed not to use the internet to obtain any answers given.

Ten schools were initially contacted about the study. All but one was in an urban area of South Yorkshire, UK, the remaining one being in London. The school in London was approached via a personal contact of one of the research team. Both independent and state schools in the urban area of South Yorkshire were targeted (eight being state-funded and two private (“independent”)) given that medical students tend to be drawn substantially from private and state schools, with around one third from the former type (Kumwenda et al., Citation2017). Of these, five accepted, of which one was an independent school. All five participating schools were located in ethnically diverse, though relatively affluent areas of major cities. The schools that agreed to participate disseminated the survey either via email or via online virtual blackboards directly to students who met the inclusion criteria. The survey was first distributed on 8 February 2019 and remained open for 1 month. One reminder was sent during this period.

The inclusion criteria for the study were:

Aged 16 years or older

Currently enrolled in lower sixth form

Taking at least one of the following A levels – biology, chemistry or psychology

The A-level subject choices were made as these were the qualifications required by the majority of medical schools for “standard entry”, but would also potentially allow admission to a psychology degree course. Participating students were given the option of entering their email addresses into a random prize draw for one of four £50 vouchers.

Analyses

In order to understand the dimensionality of the responses to the attitudinal questionnaire, a series of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were planned. These would be done, firstly, to understand any common constructs underlying the responses (“factors”/“latent variables”), and secondly, to decide how best to summarise the scores from the questionnaires for further analysis. As the responses were to a Likert scale response format, ordinal factor analysis was planned, using Mplus version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). A range of plausible factor models would be explored, ranging from one to four factors. The relationship between the attitudinal factor scores, knowledge levels and any demographic or educational factors was explored using a series of univariable linear regression analyses, using STATA 14 MP version (StataCorp LP, Citation2016).

Results

The response rate to the survey was 41%; higher than the average of 33% for online surveys (Nulty, Citation2008). A total of 254 sixth-formers commenced the survey. However, not all students completed all components of the survey. In total 186 sixth formers completed both the demographics and knowledge section and a total of 171 completed demographics, knowledge and attitudinal components. The total number of students who were provided with the opportunity to participate in the survey was 456 (i.e. this was the sampling frame). The proportion of males to female respondents was roughly equal, as was the balance of age groups (16 vs 17 years). Eighty-six of the students (46.23%) were studying more than one of the subjects with the biology and chemistry combination being the most popular. A description of the demographic and educational characteristics of the participants are shown in .

Table 1. Demographics and A level subjects studied by the respondents (n = 186).

Attitudes to psychiatry (ATP-30)

The one-factor model showed a relatively poor fit to the data and therefore was discarded. A four-factor model contained a factor where there were only three items loading specifically and heavily on it. Thus, the four-factor model was not plausible. Therefore, two and three-factor models were explored in further detail. It was noted that on a three-factor model there was a separate factor mostly loading on negatively worded items. This was assumed to be a method effect, which has been well described previously (Marsh, Citation1996). Indeed, there are no theoretical grounds for considering that “a negative attitude” and a “positive attitude” as separate constructs in relation to perceptions of psychiatry as a profession. Therefore, the two-factor model was focused on, but in order to allow for this putative method effect, the residuals from the model for negatively worded items were allowed to correlate, as recommended by Marsh (Marsh, Citation1996). This led to a confirmatory factor analytic model, depicted in , that appeared to adequately fit the data with a confirmatory fit index (CFI) of 0.91. Generally, a fit of more than 0.90 is considered adequate, with a good fit being considered with CFIs above 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

The factor scores were recovered from the two-factor model (with correlated residuals for the negatively worded items) to summarise whereabouts on a continuum, in relation to the other respondents on each dimension of attitude, the respondent lay according to his/her responses. Thus, factor scores are weighted by the loading on each factor of the responses from each participant, standardised with a mean of zero and variance of one and can be interpreted in relation to the other respondents.

The two factors derived from the factor analysis are shown in . Factor 1 relates to a negative general attitude towards psychiatry and is indicated by responses to 16 of the ATP items. Factor 2 relates to a positive attitude towards the effectiveness of treatment and is indicated by five of the ATP items. The two factors correlate −0.68, indicating a substantial degree of inverse relationship. That is, a more negative general attitude towards psychiatry is correlated with a more sceptical view of mental health treatment effectiveness

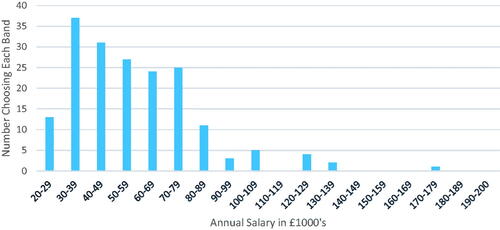

Figure 1. Distribution of the estimates of the average salary of a UK consultant psychiatrist, as reported by the sample of secondary school students.

Figure 2. Two factor model of attitudes towards psychiatry with standardised factor loadings, factor correlations, error variance and residuals. Note, correlated residuals [not all shown] are included to account for the “method effect” of negatviely worded items.

![Figure 2. Two factor model of attitudes towards psychiatry with standardised factor loadings, factor correlations, error variance and residuals. Note, correlated residuals [not all shown] are included to account for the “method effect” of negatviely worded items.](/cms/asset/96b16dbd-77ee-42bf-96c7-bd3a2c69bc68/ijmh_a_1922638_f0002_b.jpg)

outlines the results of a series of regression analyses conducted using the individual’s factor scores as the dependent (outcome) variable. As can be seen from , only female gender and studying psychology was statistically significantly (p < 0.05) associated with a relatively less negative general attitude towards psychiatry. Likewise, those who were studying psychology were more positive about the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments, whilst those studying chemistry were more negative about this issue.

Table 2. Results from a regression analysis predicting the factor scores from the attitudinal questionnaire from the demographic and educational characteristics of the respondents.

Knowledge component

Participants were asked to respond to the statement “To become a psychiatrist someone would require a degree in which subject?” by choosing one or more of “medicine”, “psychology”, “pharmacology” and “sociology”. Seventy-four percent of respondents erroneously reported that a psychology degree was required whilst only 57% correctly identified that a medical degree was mandated. Many (64%) respondents also commonly indicated that they believed that the length of time to become a consultant psychiatrist was 5–8 years from starting university. This is significantly shorter than the 5 years of medical school, 2 years of foundation training, and 6 years of specialist psychiatry training required in the UK to become a fully qualified consultant psychiatrist.

Respondents were on the whole aware of which specialties were psychiatric specialties when presented with a list containing general adult, child/adolescent, learning disability, psychotherapy and older adult, intermixed with a list of non-psychiatric specialties (endocrinology, respiratory, cardiac, gastrointestinal and dermatology). The only exception was forensic which caused a 48/52 split in favour of it erroneously being a non-psychiatric specialty.

Participants were asked to distribute a list of conditions into two boxes, one titled “Psychiatrist” and one titled “Not a Psychiatrist”. The majority of the conditions listed were placed in the correct group by respondents. “Dementia” and “Marital Problems” were less unanimous with a 56/44 and 60/40 split between “Psychiatrist” and “non-Psychiatrist” respectively. This may be a result of neurologists also seeing patients with dementia and a lack of clarity regarding the difference between psychiatrists and psychologists/therapists who may see people for marital problems.

Respondents were asked to make an estimation of the annual salary of a consultant psychiatrist in the UK. They were informed that the mean UK annual salary for a full-time employee is £28,677 (Office for National Statistics, Citation2017). They were constrained to a minimum salary of £10,000 and a maximum of £200,000. The respondents gave a mean predicted salary of £60,000 and a median value of £52,000. This is much lower than the actual salaries, with the mean likely to be around £90,000 to £110,000 per year in the National Health Service (depending on experience and discretionary pay awards) though will be higher in the private (independent) healthcare sector (British Medical Association, Citation2020).

Regression analyses were also used to model the measure of the relationships between the independent (predictor) variables and the total knowledge score obtained by the respondent, which was calculated simply by totalling the number of correct answers in the knowledge section. The results are shown in . As can be seen, there were no were statistically significant (p < 0.05) predictors of knowledge of psychiatry as a career. However, there was a trend of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.05) for those with less negative attitudes towards psychiatry to provide more accurate answers to the knowledge questions.

Table 3. Results from a regression analysis predicting the total knowledge scores from the demographic and educational characteristics of the respondents, as well as their attitudinal factor scores.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the knowledge and attitudes towards psychiatry amongst a diverse group of lower sixth form students, studying science subjects, but who have not necessarily shown any prior interest in studying medicine. The findings highlight the lack of knowledge regarding the psychiatric career pathway, with only just over half of respondents identifying that a medical degree is required. Respondents also underestimated the length of training time and the average salary for a consultant. However, the participants demonstrated a reasonable ability to identify which conditions psychiatrists treated and the subspecialties of practice.

In terms of attitudes, two, related, factors underlying responses to the ATP were identified. Males tended to hold more negative views of psychiatry in general, compared to female students. Unsurprisingly, those studying psychology generally reported more positive attitudes towards both the specialty and the effectiveness of treatment, compared to those taking chemistry at advanced level. Those with more accurate knowledge of psychiatry tended to report a more positive attitude. It is notable that the present findings in relation to knowledge of psychiatry are broadly comparable to those reported previously for the general public (Williams et al., Citation2001).

The strengths of this study include the relatively high response rate of 41% for this kind of survey. The incentive of a prize draw upon completion of the study likely helped to increase the response rates. Nevertheless, there is still the possibility that response bias may have influenced the results, with perhaps those with more favourable or negative views being more likely to complete the questionnaire. A further strength is that this survey accessed a large number of school students who, based on their subject choice, may have subsequently have been in a position to apply for either a medicine or psychology course. Nevertheless, there are some potential limitations and weaknesses present. Firstly, it was noted that there was a drop-off in respondents from the point of opening the survey link to completion. It is important to consider why participants dropped out at each stage. The drop out from consent to the completion of demographics may have been related to students not wishing to give out their demographic information. This was a mandatory section of the survey and non-completion meant participants could not progress. A further limitation is that the schools participating were drawn from relatively affluent urban areas in South Yorkshire and London. More diverse sample schools may have rendered the results more generalizable. This could have been addressed by the use of a wider sampling frame of schools, and incentivising their participation in the study. Nevertheless, almost all medical students are drawn from relatively advantaged backgrounds, with 20% of schools in England supplying 80% of the country’s medical students (Mwandigha et al., Citation2018). Moreover, a recent study highlighted that UK medical graduates who choose a career in psychiatry were more likely to identify as of white ethnicity and be privately educated (Lambe et al., Citation2019). Thus, our findings may apply to the current school students who may be likely to enter medical school. However, further efforts to widen access to medicine (Medical Schools Council, Citation2018), especially in the light of the recent expansion in UK-based medical school places may influence the demographics of doctors in training.

This study provides valuable information for those designing and deploying recruitment strategies to address the shortage of psychiatrists. Such campaigns should be evaluated using the absolute number of trainees recruited, in addition to the fill rates, as both are relevant outcomes of interest. The former metric may be more appropriate when engaged in workforce planning and considering the training pipeline through to consultant posts. These findings highlight that imparting factually accurate information relating to a career path in psychiatry is at least as important as addressing negative, or stigmatised attitudes towards mental health issues. Indeed, stigmatised attitudes towards mental health, particularly amongst younger people, seem to be declining (Henderson et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, recruitment campaigns are an opportunity to reinforce the message that physical and mental health should have parity of esteem. Secondly, recruitment campaigns should be targeting those students studying psychology who might already be considering clinical psychology as a career. If this group can be encouraged to enter medical school and mentored through training then they may help form a new cohort of future psychiatrists. There is no evidence, currently, that medical students who have sat A-level psychology are more likely than others to become psychiatrists, although interestingly US medical students who had studied psychology at college were more likely to choose the speciality (Goldenberg et al., Citation2017). However, comparisons with North America, where medicine is a postgraduate degree, must be made only tentatively, given the very different educational systems. Nevertheless, this observation may further emphasise the need to go “upstream” and engage with students before they decide to apply to medical school (Mukherjee et al., Citation2013). In addition, the fact that increasing numbers of UK medical schools are recognising psychology as a science subject, as well as abandoning advanced level chemistry as a core requirement for admission, is to be welcomed (Medical Schools Council, Citation2020). Such changes may be expected to take some time to filter through to those school students aspiring to be doctors. For the time being the vast majority of medical school applicants in the UK can be expected to continue to focus on achievement at the three sciences and/or, mathematics.

The UK Royal College of Psychiatrists has run summer schools for secondary school students as part of their recruitment campaign. However, if school students fail to understand the main similarities and differences between a career in clinical psychology and psychiatry they are less likely to appropriately attend a psychiatry summer school. Nevertheless, attention should continue to be paid to those already in medical school who may consider a career in psychological medicine. Indeed, there is evidence of “psychiatry bashing” as part of the “hidden curriculum” of medical school, resulting in the Royal College of Psychiatrists launching a social media “Ban the Bash” campaign (Ajaz et al., Citation2016). With such issues in mind, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has issued guidance to medical schools as part of their “Choose Psychiatry” strategy (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2019).

In conclusion, this study provides important information that can shape future psychiatric recruitment strategies. Such campaigns should include, as a key component, the provision of accurate factual information to secondary school students. Only then will many potential future psychiatrists understand the speciality represents a well remunerated, worthwhile and rewarding career that makes a difference to thousands of patients and their families daily.

Disclosure statement

PAT is a Fellow and LJM a Member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber NHS Trust, the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajaz, A., David, R., Brown, D., Smuk, M., & Korszun, A. (2016). BASH: Badmouthing, attitudes and stigmatisation in healthcare as experienced by medical students. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.115.053140

- British Medical Association. (2020). Consultant pay scales in England. https://www.bma.org.uk/pay-and-contracts/pay/consultants-pay-scales/pay-scales-for-consultants-in-england

- Burra, P., Kalin, R., Leichner, P., Waldron, J. J., Handforth, J. R., Jarrett, F. J., & Amara, I. B. (1982). The ATP 30-a scale for measuring medical students’ attitudes to psychiatry. Medical Education, 16(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1982.tb01216.x

- Deb, T., & Lomax, G. A. (2014). Why don’t more doctors choose a career in psychiatry? BMJ, 348, f7714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7714

- Farooq, K., Lydall, G. J., Malik, A., Ndetei, D. M., Group, I., & Bhugra, D. (2014). Why medical students choose psychiatry - A 20 country cross-sectional survey. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-12

- Fysh, T. H. S., Thomas, G., & Ellis, H. (2007). Who wants to be a surgeon? A study of 300 first year medical students. BMC Medical Education, 7(1), 2.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-2

- General Medical Council. (2018). What our data tells us about locum doctors – Working paper 5. G. M. Council.

- Goldenberg, M. N., Williams, D. K., & Spollen, J. J. (2017). Stability of and factors related to medical student specialty choice of psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(9), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020159

- Health Education England North-West. (2020a). Core training in psychiatry (CT-1) recruitment: 2020. https://nwpgmd.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/Round%201%20%26%20R1%20Re-advert%20Aug%202020%20-%20CT1%20Psychiatry%20Fill%20Rates%20-%20PUBLISHED.pdf

- Health Education England North-West. (2020b). Higher specialist training in psychiatry (ST-4) recruitment: 2020. https://www.nwpgmd.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/ST4%20Psychiatry%20Aug%202019%20%26%20Feb%202020%20Fill%20rates.pdf

- Henderson, C., Potts, L., & Robinson, E. J. (2020). Mental illness stigma after a decade of time to change England: Inequalities as targets for further improvement. European Journal of Public Health, 30(3), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa013

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Kumwenda, B., Cleland, J. A., Walker, K., Lee, A. J., & Greatrix, R. (2017). The relationship between school type and academic performance at medical school: A national, multi-cohort study. BMJ Open, 7(8), e016291. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016291

- Lambe, P. J., Gale, T. C. E., Price, T., & Roberts, M. J. (2019). Sociodemographic and educational characteristics of doctors applying for psychiatry training in the UK: Secondary analysis of data from the UK Medical Education Database project. BJPsych Bulletin, 43(6), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2019.33

- Lyons, Z., & Janca, A. (2015). Impact of a psychiatry clerkship on stigma, attitudes towards psychiatry, and psychiatry as a career choice. BMC Medical Education, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0307-4

- Maidment, R., Livingston, G., Katona, M., Whitaker, E., & Katona, C. (2003). Carry on shrinking: Career intentions and attitudes to psychiatry of prospective medical students. Psychiatric Bulletin, 27(1), 30–32. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.27.1.30

- Marsh, H. W. (1996). Positive and negative global self-esteem: A substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.810

- McGhee, P. (2015). What are the most popular degree courses? BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-32230793

- Medical Schools Council. (2018). Selection Alliance 2018 Report: An update on the Medical Schools Council’s work in selection and widening participation.

- Medical Schools Council. (2020). Entry requirements for UK medical schools: 2021 requirements. T. M. S. Council.

- Mukherjee, K., Maier, M., & Wessely, S. (2013). UK crisis in recruitment into psychiatric training. The Psychiatrist, 37(6), 210–214. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.112.040873

- Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2017). MPlus version 8. Muthen and Muthen.

- Mwandigha, L. M., Tiffin, P. A., Paton, L. W., Kasim, A. S., & Böhnke, J. R. (2018). What is the effect of secondary (high) schooling on subsequent medical school performance? A national, UK-based, cohort study. BMJ Open, 8(5), e020291. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020291

- Norredam, M., & Album, D. (2007). Prestige and its significance for medical specialties and diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 35(6), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940701362137

- Nulty, D. D. (2008). The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930701293231

- Office for National Statistics. (2017). Annual survey of hours and earnings: 2017 provisional and 2016 revised results https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/annualsurveyofhoursandearnings/2017provisionaland2016revisedresults#main-points

- Qureshi, H., Holt, C., Mirvis, R., Cross, S., Hussain, O., Hutchings, H., Marshall, E., Turner, F., & Jones, C. (2016). Introducing PEEP: The psychiatry early experience programme. European Psychiatry, 33(S1), S30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.853

- Ride, J., Kasteridis, P., Gutacker, N., Doran, T., Rice, N., Gravelle, H., Kendrick, T., Mason, A., Goddard, M., Siddiqi, N., Gilbody, S., Williams, R., Aylott, L., Dare, C., & Jacobs, R. (2019). Impact of family practice continuity of care on unplanned hospital use for people with serious mental illness. Health Services Research, 54(6), 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13211

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2015). A guide to psychiatry in the foundation programme for supervisors and foundation trainees. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/become-a-psychiatrist/foundation-doctors/good_practice-_guide_psychiatry_in_foundation_programme.pdf?sfvrsn=a5ed18d9_4

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2017). Recruitment strategy: January 2017-December 2019. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/become-a-psychiatrist/help-us-promote-psychiatry/our-strategy–-prip-strategy-2017-19-final.pdf?sfvrsn=a3b995d6_2

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2019). Choose psychiatry: Guidance for medical schools. (https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/become-a-psychiatrist/guidance-for-medical-schools-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=20f46cae_2

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2020a). Census 2019: Workforce figures for consultant psychiatrists, specialty doctor psychiatrists and Physician Associates in Mental Health. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/workforce/census-final-update060720-1.pdf?sfvrsn=bffa4b43_8

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2020b). Choose psychiatry: Choose to make a difference. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/become-a-psychiatrist/choose-psychiatry

- Shields, G., Ng, R., Ventriglio, A., Castaldelli-Maia, J., Torales, J., & Bhugra, D. (2017). WPA position statement on recruitment in psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 113–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20392

- StataCorp LP. (2016). Stata MP for Windows 64-bit. StataCorp.

- Stuart, H., Sartorius, N., & Liinamaa, T. (2015). Images of psychiatry and psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 131(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12368

- The Medic Portal. (2019). What A-levels do you need to be a doctor? https://www.themedicportal.com/application-guide/choosing-a-medical-school/what-a-levels-do-you-need-to-be-a-doctor/

- Williams, A., Cheyne, A., & MacDonald, S. (2001). The public’s knowledge of psychiatrists: Questionnaire survey. Psychiatric Bulletin, 25(11), 429–432. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.25.11.429