Abstract

Background

National policies and guidelines advocate that mental health practitioners employ positive risk management in clinical practice. However, there is currently a lack of clear guidance and definitions around this technique. Policy reviews can clarify complex issues by qualitatively synthesising common themes in the literature.

Aims

To review and thematically analyse national policy and guidelines on positive risk management to understand how it is conceptualised and defined.

Method

The authors completed a systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42019122322) of grey literature databases (NICE, NHS England, UK Government) to identify policies and guidelines published between 1980 and April 2019. They analysed the results using thematic analysis.

Results

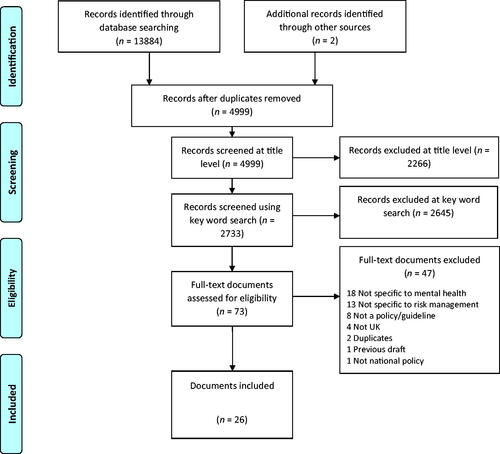

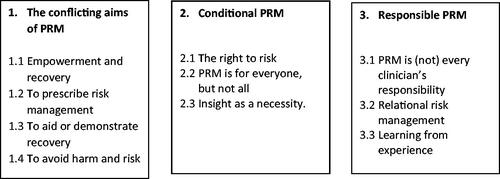

The authors screened 4999 documents, identifying 7 eligible policies and 19 guidelines. Qualitative synthesis resulted in three main themes: i) the conflicting aims of positive risk management; ii) conditional positive risk management; and iii) responsible positive risk management.

Conclusions

Analysis highlighted discrepancies and tensions in the conceptualisation of positive risk management both within and between policies. Documents described positive risk management in different and contradictory terms, making it challenging to identify what it is, when it should be employed, and by whom. Five policies offered only very limited definitions of positive risk management.

Introduction

National policies and guidelines in the United Kingdom advocate that mental health practitioners use positive risk management (PRM) when working with service users. Although definitions of PRM vary, in general terms, it is the process of collaboratively ensuring the safety and wellbeing of service users while promoting their quality of life and recovery (Skills for Care & Skills for Health, Citation2014), based on the rationale that risk management strategies are more effective when developed in partnership with service users and their carers or family members (Department of Health, Citation2010).

Research indicates that PRM can reduce risk, whilst improving functioning and quality of life, aiding the clinical relationship between practitioner and service user (Robertson & Collinson, Citation2011) and building trust (Hall & Duperouzel, Citation2011) and collaboration (Langan & Lindow, Citation2004). Despite this, staff rarely use PRM in practice with only 38% of outpatients (Prokešová et al., Citation2016) and just over 10% of inpatients being involved in their risk management discussions and plans (Coffey et al., Citation2019). Additionally, in community settings, 36% of care plans are developed with service user involvement, yet only 12% of risk management plans include service user collaboration (Coffey et al., Citation2017). Therefore, implementation of PRM remains limited.

Although guidelines and policies aim to inform and direct practice, it is unclear whether they lead to consistent changes in the behaviours of mental health practitioners (Carthey et al., Citation2011; Timmermans & Mauck, Citation2005). Barriers faced in the implementation of guidelines and policies include a lack of awareness of existing recommendations, a lack of supporting evidence (Corey et al., Citation2018), disagreement with the recommendations, and a lack of enforcement (Logan et al., Citation2011). Research has shown that definitions and recommendations in guidelines and policy documents are sometimes inconsistent and contain conflicting information, which may also reduce uptake of the recommended practices (Drennan et al., Citation2014). Varied and unclear conceptualisations and guidance of risk management could hamper implementation and result in diverse and unstandardised approaches to care (Reddington, Citation2017). To our knowledge, there has been no previous review of policies on PRM. Thus, it remains uncertain whether, or to what extent, the guidelines are clear, consistent and operationalised.

Policy reviews can be a useful way to clarify complex issues by compressing relevant information in a manner that promotes decision making (Walker, Citation2000). They summarise grey literature and, compared to systematic reviews of empirical research, may capture current knowledge, which is less subject to publication bias (Bellefontaine & Lee, Citation2014). Moreover, guidelines synthesise essential research findings into practical statements and recommendations (Kredo et al., Citation2016) and in the absence of available systematic reviews, can influence clinical practice (Meats et al., Citation2007).

Aims of the study

The objective of the current systematic policy review was to explore how PRM was conceptualised and defined within policies and guidelines for adult mental health services using thematic synthesis. A further aim was to explore how, and in which contexts, policymakers justified PRM, and the existing guidance on implementation.

Materials and method

The lead author conducted a systematic search of three online policy and guideline repositories in April 2019 (PROSPERO: CRD42019122322). These were the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (www.evidence.nhs.uk), NHS England publications (www.england.nhs.uk/publication), and United Kingdom Government publications (www.gov.uk/government/publications) website. For each database, the authors entered the term mental health with one of four terms relating to common forms of risk (risk, self-harm, suicide and aggress*). The search in the NICE evidence database was restricted to policy and strategy documents, NHS England publications to publications and UK Government publications to guidance, policy papers and health and social care. This is a systematic review of policy, rather than empirical literature. However, where relevant the authors attempted to adhere to PRISMA guidelines.

Eligibility

This review focused on UK national policies and guidelines. The authors defined policies as “broad statement of goals, objectives and means that create the framework for activity” and “courses of action (and inaction) that affect the set of institutions, organisations, services and funding arrangements of the health system” (Buse et al., Citation2005, p. 4–6). Guidelines were defined as “decision-support tools… designed to specify practice” (Tannenbaum, Citation2005, p. 166). The authors included policies and guidelines, even if they did not make recommendations on a specific course of action.

The eligibility criteria included any policies and guidelines; i) aimed at adults (≥18) accessing mental health services; ii) dated from ≥1980 to be in line with modern classification systems of psychiatric disorders; and iii) that concerned risk management processes defined as “the actions taken, based on a risk assessment, that are designed to prevent or limit undesirable outcomes” (Department of Health, Citation2009, p. 61). The authors excluded policies and guidelines if they; i) solely referred to learning disability, physical health, dementia or organic disorders; ii) were previous drafts of old policies that were no longer available or did not include content changes; iii) were manuscripts which did not constitute whole policies, such as pamphlets or flyers. The current review was restricted to UK policies and guidelines only.

Screening

Duplicates were removed in two stages; initially by combining the four individual searches for each database and removing duplicates within each database, and then by combining the results from the three databases and removing duplicates across the three databases. Screening occurred in three stages. First, the lead author (DJ) screened the titles of the identified policies. An independent postgraduate researcher double rated 12.5% (k = 625) of titles with strong levels of agreement (92.32%; ᴋ = .83). Most discrepancies were due to the primary screener being overly inclusive. The team reviewed disagreements until consensus was reached. Second, the lead author screened documents using a word search function within the documents using five separate terms pertaining to PRM (collaborative risk, supported decision, proactive risk, therapeutic risk and positive risk) and removed documents that did not contain any of these keywords. Keyword terms were identified based on the research teams initial scoping searches and screening of the literature, and clinical experience. These were discussed at multiple meetings and consensus was reached. However, the authors acknowledge that the approach might have omitted certain terms or documents, although the identification of 13884 results through database searching, and the inclusion of 26 documents, suggests that the search was comprehensive. Third, the lead author read the resultant full policies and guidelines. The second (ST) and last (JPC) authors also second screened all eligible full documents, resolving any discrepancies by consensus. Lastly, to ensure the detection of all eligible documents, the lead author screened the reference list of included policies and guidelines.

Data extraction

Eligible documents were uploaded onto NVivo (QSR International PTY LTD. Version 12, 2019), which was used to identify sections relevant to the research question and analyse the data.

Data analysis

Researchers frequently use thematic analysis to interpret primary qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019), which has been adapted to the analysis of secondary qualitative data (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Thematic synthesis in the current review was based on a three-step approach: line-by-line coding, organisation of codes into descriptive themes, and the development of analytical themes. As the research question focused on meaning, specifically, how policymakers conceptualised PRM, this review was consistent with the qualitative paradigm of critical realism, which contrasted with the positivist assumptions of one measurable, generalisable truth. A critical realism paradigm posits that knowledge of reality is imperfect and can only be understood through perspectives and dialogue (Fletcher, Citation2017). The authors deemed a thematic synthesis approach most appropriate as it was not bound to specific research questions and approaches. As the current review targeted how policymakers conceptualise PRM, we required an approach that considered the social context in which policies and guidelines were developed, as well as enough flexibility to analyse pre-generated data with a specific focus. Thematic synthesis, therefore, provided theoretical flexibility, which mapped onto the research question and data collection process, culminating in the analysis of themes across the different documents, grounding interpretations in the data. The theoretical underpinnings and assumptions that guided the research were based on the qualitative paradigm and a contextual stance which presumed that there were multiple truths shaped by peoples’ interpretations and social contexts, as well as an acknowledgement of how individuals made meaning of their experience, and in turn, the ways the broader social context impacted on those meanings. Policies and guidelines themselves are created with the aim of shaping the social context in a specific direction and hope to guide individuals' interpretations. As such, policies and guidelines reflect the social context as well as the document authors’ opinions and interpretations of the social context. Policies and guidelines are intended to drive and dictate practice but are also themselves a reflection of how the document authors made meaning of their experiences and contexts. Therefore, a deductive approach to coding and theme development was employed, as this allowed the researcher to focus specifically on conceptualisations of PRM. The authors compared data within and across documents, meaning they coded subsequent documents into pre-existing codes, and created new codes where necessary. They developed latent themes, which reported concepts and assumptions underpinning the data. The analysis adhered to the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) guidelines (Tong et al., Citation2012).

It was noteworthy that the lead author analysed the data with prior assumptions that likely influenced the coding process. To understand this effect, initial coding included regular team discussions on data coding, assumptions, and obvious omissions. The purpose of this was not to establish inter-rater reliability, as thematic synthesis was an active and reflexive process that assumed that there was no one accurate reality in the data, rather to ensure that the codes were complex, nuanced and insightful.

Results

The authors summarise the screening process in . Sixty-five policies and guidelines were not freely accessible so the authors contacted policymakers to obtain copies of the documents. Subsequently, we excluded 15 documents due to; i) the authors not responding to the request/unable to contact authors (n = 12); ii) the documents no longer being available (n = 2); and iii) documents only being provided to licensed organisations (n = 1). In total, we identified 26 documents, of which 7 were policies, and 19 were guidelines (see ). The oldest document included was dated 2004, as older documents did not appear to discuss PRM.

Table 1. Characteristics of included policies/guidelines.

Five eligible policies and guidelines had insufficient data to thematically analyse (documents 22–26). Results were therefore categorised into two groups: low data and high data. The authors classified documents mentioning PRM, or aspects thereof, but not elaborating on these, as low data, which were not entered into the thematic analysis, but considered in the wider context of the review. These five documents did not offer a definition or explanation of PRM, or the definitions were too poorly defined to analyse.

Policymakers used different terms to describe PRM, listed in . Of the 26 documents, seven specifically referred to the term PRM, of which five offered some definition. Eighteen documents mentioned positive risk-taking, of which 15 offered some definition of the concept.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis generated three themes relating to how PRM was conceptualised and defined within national policies and guidelines (). The authors present extracts from the documents to demonstrate the interpretative adequacy of the analysis with further examples being available in . Numbers in brackets refer to the document numbers as per .

Table 2. Additional extracts illustrating themes.

Theme 1: the conflicting aims of PRM

The first theme pertains to the aims of PRM. Across policies and guidelines, policymakers described PRM as a collaborative, strengths-based approach that enhanced service users' quality of life. However, contradictions within and across documents were evident in terms of emphasis on avoiding or taking necessary risks, enabling or evidencing recovery, and collaborative or prescriptive risk management, as discussed in the four subthemes below.

Empowerment and recovery

Policymakers recognised PRM as something that had the potential to empower service users. Seventeen documents explicitly recommended collaborative risk management (1–3, 5–6, 8, 10–12, 14–21) and nine recommended the identification and amplification of strengths to provide service users with hope, engagement and drive for recovery (1, 5, 8, 10–12, 16–18). Within a strengths-based approach, policymakers recommended taking positive risks to improve the quality of life for service users by helping them to feel empowered and more independent from services. At the core of PRM across policies, was therefore, the principle that service users could manage their risks, given the right tools:

People can and do become skilled in managing their own risks (NHS Confederation, Citation2014b, p. 12).

From the perspective of a strengths-based approach, policymakers regarded PRM as not being about avoiding risk. Empowerment, as a primary aim of PRM was evident in six documents (4–5, 7, 16–17, 21). Policymakers recommended taking positive risks and empowering service users to learning, building resources, and gaining independence, which they felt could lead to faster recovery. The following quote illustrates how policymakers argued that risk reduction should be balanced against empowerment and recovery:

Choosing the safest possible option for care and treatment can be disempowering for the service user and counter-productive for his/her recovery (Department of Health, Citation2010, p. 11).

To prescribe risk management

There were also apparent contradictions within and across documents with regards to collaboration. Although policymakers emphasised the importance of collaboration in risk management, documents employed language that also implied that practitioner-led approaches were required. For instance, the Healthcare Improvement Scotland (Citation2009) document initially recommended a collaborative approach, yet later in the document, stated that: 'Every time a problem is identified, a strategy should be suggested and discussed' p. 17. The language used implies that clinicians should devise a plan, which they should then discuss with the service user, rather than develop this together. It reduces the emphasis on service users providing their own ideas and solutions to risk. Thus, clinicians are encouraged to take a more prescriptive role in the decision-making. Fricker (Citation2007) argued that this was a type of epistemic injustice, more specifically testimonial injustice, as service users level of credibility is deflated by practitioners undermining the service users knowledge of themselves (Crichton et al., Citation2017).

Prescriptive risk management was advocated through the use of the mental health act, for example, in situations where service users were considered to be lacking in insight. However, most documents recommended such practices as a last resort. Of the eight documents that referred to using the mental health act (7–8, 10–11, 14–17), five described doing so as a form of prescribed risk management (7, 10, 15–17).

If decision-making support is not sought or accepted … appropriate safeguarding steps should be considered, as per the Adult Support and Protection Act (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, Citation2016, p. 19).

Thus, practitioner-led approaches were deemed to be appropriate during cases of safeguarding and where the service user disagreed with the practitioners’ views. It was noteworthy that only one document (Department of Health, Citation2009) explicitly emphasised the importance of maintaining collaboration between service users and practitioners, even when more prescriptive measures were required.

To aid or demonstrate recovery

Policymakers described PRM as a method for helping service users to recover from mental health issues, but also as a marker for having achieved recovery. Seventeen documents discussed recovery from mental health difficulties as a direct aim of PRM (1, 3–5, 7–14, 16–19, 21). They suggested that taking positive risks was necessary to enhance the service users’ quality of life and ultimately achieve recovery. For example, the 2010 Department of Health (Citation2010) document identified that risk might inevitably increase in the short-term as part of a necessary and helpful longer-term recovery process

Whilst recovery-orientated services may increase risks, it is sometimes necessary in order for the service user to learn and grow (Department of Health, Citation2010, p. 11).

In contrast to this, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Citation2016) and NHS Confederation (Citation2014a) documents described PRM as something that should be used to determine whether recovery had been reached. Therefore, inconsistency existed across documents as to the aims of PRM.

A focus on recovery allows professionals to take risks to allow patients to demonstrate their progress (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2016, p. 5).

To avoid harm and risk

A further aim of PRM, as described by policymakers, was the reduction and avoidance of harm and risk. Ten documents (1, 4, 6, 8, 10–11, 14, 16–18) explicitly talked about this aim: 'good [risk] management can reduce and prevent harm’ (Department of Health, Citation2009, p. 6 and 16). However, consensus on the degree to which harm should be removed varied across documents. Certain policymakers advocated for the removal of any harm and risk (6, 11, 17), while seven documents recommended a minimisation of harm (1, 4, 8, 10, 14, 16, 18). Several documents acknowledged how societal attitudes can influence policies and guidelines, and in this context, risk-averse social attitudes might reflect a desire to avoid risk. For example, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Citation2016) document noted that attitudes may become more restrictive over time: “Society has become, in general, more risk averse” (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2016, p. 8). Other documents also reflected such attitudes, emphasising that: 'concern for safety remains uppermost’ (NHS Confederation, Citation2014b, p. 12).

Not all documents agreed on avoidance of harm and risk as a key aim for PRM. Eight documents (7–11, 16–17, 20) stated that overemphasis on risk avoidance was potentially harmful. These documents described how preoccupation with risk was detrimental to service users' progress. They suggested that classifying patients as high risk, provided reduced opportunity for empowerment and recovery. Although few documents gave concrete examples, the NHS Confederation (Citation2014a) guideline discussed the importance of unescorted leave and how taking a risk, such as leave, provided service users with hope for their recovery. The following quote illustrates how policymakers stated that services and practitioners should not avoid all risks:

just as wise parents resist the temptation to keep their children metaphorically wrapped up in cotton wool, so too we must avoid the temptation always to put the … health and safety … before everything else (Department of Health, Citation2015, p. 47)

Theme 2: conditional PRM

Documents varied in their outlines of which context and service users were best suited to PRM. Although not true of all, several policymakers suggested that PRM was suitable for all service users. The three subthemes elaborate on the factors that documents advocated taking into account when conducting PRM.

The right to risk

Many documents referred to service users' right to take positive risks, including their right to make decisions and change their mind about those decisions. This subtheme pertains to the idea of some form of risk being inevitable and unavoidable ('The fact is that all life involves risk'; Department of Health, Citation2015, p. 47). Policymakers advocated that practitioners should remain aware that risk can never be truly eliminated, and that service users had a right to decide to take risks and make decisions, despite the possible drawbacks of doing so. Eight documents described the concept of risk being intrinsic to living a full life (7–11, 16–17, 19).

People have the right to learn from experience, to revisit decisions and change their minds and make decisions that others do not agree with (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, Citation2016, p. 18)

Policymakers did include caveats to the right to risk, suggesting that service users should be able to take some risks. For example, the NHS Confederation (2014) and the Department of Health (Citation2010) documents divided risk into two categories: risks that service users had a right to take to aid their recovery, and risks that must be minimised (risk to self, others, from others and vulnerability). Policymakers did not provide further clarification what risks service users had a right to experience. Other documents categorised risk as falling into the four areas: risk to self, risk to others, risk to children/vulnerable adults, and risk from others. Although policymakers consistently advocated the minimisation or avoidance of these risks, they provided no specific clarification on which, if any, risks service users did have a right to take. The NHS Confederation (Citation2014a) guideline referred to 'major risks' and 'everyday risks' (p. 13), although it acknowledged that such a distinction could be easily blurred, resulting in a risk aversive culture.

It is important that there is an awareness of the risks that must be minimised (i.e. harm to self, harm to others, harm to children/vulnerable adults, and harm from others) and the risks that people have a right to experience in order to progress towards their goals of recovery (Department of Health, Citation2010, p. 10)

PRM is for everyone, but not all

Most policymakers recommended that PRM should be made routinely available for all service users and by all mental health services. For example, the Department of Health guideline (2010) stipulated that: 'Mental health services must support personal recovery, move beyond risk avoidance and towards positive risk taking' p. 10. Contradictorily, many policies advocated that PRM was advisable only for low risk or non-risky circumstances. The Royal College of Psychiatrists (Citation2007) guideline recommended using PRM for “predictable crises” (p. 51), but provided no specific guidance as to what constituted a predictable crisis. Categorising risk into either low or high categories was also common across documents, with low risk categories seen as more appropriate for PRM, although policymakers also used alternative forms of categorisation. For example, some documents made distinctions according to historic risk (Department of Health, Citation2009), diagnoses (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2016), and others simply stated that PRM was not suitable for all service users (Department of Health, Citation2010). Policymakers often stated that service users labelled as high risk or unpredictable are unsuitable for PRM.

It might be possible to reduce risk in some settings, the risks posed by those with mental disorders are difficult to predict (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2016, p. 4)

Insight as a necessity

All documents regarded the successful use of PRM as being contingent on service users' insight into their behaviours and decisions. What was meant by insight varied with most policymakers defining it as the service user's ability to understand the consequences of their behaviour. Five documents (1, 7, 9–10, 17) explicitly described factors that could affect service users' insight. These included service users' mental health status, stigma, lack of support, lack of risk recognition and practitioners' attitudes. Determining whether someone had insight was influenced predominantly by practitioners' attitudes and beliefs and linked closely to practitioners’ own reflective abilities. Across documents, policymakers described insight as something that made the process of collaborative risk management more manageable and had benefits for service users:

supporting an individual to … understand the potential consequences of their decision encourages empowerment (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, Citation2016, p. 19)

All policies and guidelines stipulated that clinicians should make every effort to facilitate service users' understanding of themselves, whilst acknowledging that this was not always possible. Policymakers recommended PRM for service users who possessed an understanding of their behaviour, a judgement influenced by practitioners' own beliefs and attitudes, for example: “[staff] do not presume a lack of capacity just because a person is making a decision they consider to be unwise or otherwise detrimental” (Department of Health, Citation2015, p. 15). As documents acknowledged that insight was often influenced by other factors, it raises questions over the utility of the concept. Additionally, documents stated that insight is based on practitioners’ own beliefs and attitudes. However, they did not clarify why and how this concept is important for risk management when it is described as subjective. It remains unclear exactly what insight is and how this should be determined, although all documents noted that it was important to ascertain.

Theme 3: responsible PRM

The last core theme pertains to the recommendations that policymakers described as necessary requirements from services and practitioners to implement PRM. Not all policymakers provided practical recommendations, and some recommendations were inconsistent across documents. The subthemes elaborate on key recommendations made by policymakers.

PRM is (not) every clinician’s responsibility

The majority of policymakers described PRM as everyone's responsibility; often referred to as a cultural approach to risk management. This approach relied on all practitioners being able to employ PRM, regardless of their role or skill set: 'all practitioners have a key role to play in this' (Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Citation2009, p. 15). Eight policymakers (8, 10–13, 16–18) outlined a PRM culture that included senior-level endorsements, board commitments, transparency and a no-blame culture based on promoting reporting and learning. Documents viewed this culture as requiring the collaboration of service users, the public and professionals. They, therefore, emphasised the importance of everyone being involved in the PRM process and not relying on a specific skill set. Contrary to this, in a subgroup of documents, PRM was positioned as a tool to be harnessed more by experienced and skilled professionals. For example, the Department of Health (Citation2016) guideline described PRM as a specific skill set that only certain practitioners possessed. It recommended that risk management was an essential skill for all practitioners, yet PRM skills were only a requirement for 'experienced social workers' p. 69. The guidance acknowledged that practitioners’ progression to being considered an experienced social worker was often determined by the practitioner's ability to manage demanding situations and complexities, whilst also suggesting that PRM was more challenging to implement compared to general risk management strategies. Similarly, the Department of Health (Citation2009) guideline emphasised PRM as a complicated process requiring appropriate levels of skill and experience to use correctly. This contrasts with the Royal College of Psychiatrist's (2016) document advocating PRM as a strategy for all practitioners, regardless of seniority. Therefore, across policies and guidelines, it remained unclear which practitioners should be implementing PRM.

Relational risk management

Policymakers described the relationships that practitioners had with themselves and with service users as playing a key role in effective PRM. Policies often emphasised the importance of the relationship between practitioners and service users as the most valuable and effective component of PRM:

The interaction between clinician and patient is crucial; good relationships make assessment easier and more accurate, and might reduce risk (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2016, p. 34)

The above quote illustrates the importance of the relationship in terms of improving the quality of the risk assessment. In agreement is the NHS Confederations (Citation2014a) guideline which stated that good relationships lead 'to more sophisticated and better informed management plans' p. 14. Seven policymakers (7–8, 10–11, 16–18) explicitly discussed the importance of relationships and 17 implicitly advocated for relational security. This indicates the importance of relationships and the value of focusing on and building effective clinical relationships. However, documents often referred to the therapeutic relationships in terms of gains for practitioners. This may inadvertently position the needs of service users as secondary.

Also important was the relationships practitioners had with themselves. As part of PRM, four policymakers (1, 7, 13, 16) recommended practitioners reflect of the factors that might influence their risk management decisions suggesting that 'perceptions of risk are different for different people’ (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, Citation2016, p. 19). Policymakers regarded the ability to reflect as enhancing the risk management process. For example, the Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health (Citation2013) document encouraged staff to be recruited based on their attitude towards risk management, and the Department of Health & Social Care (Citation2019) guideline explicitly stated the importance of decisions not being based on assumptions. Both practices relied on practitioners having some self-awareness and reflective capacity. The Department of Health (Citation2009) guideline provided some guidance on how this could be achieved through reflective practice: 'It is important for professionals to be aware of and reflect upon the factors that influence their decision-making' (Department of Health, Citation2009, p. 32–33). It was noteworthy that one document stated that the way that clinicians understand and interpret PRM could also cyclically impact on their attitudes and beliefs: 'The term is easily misunderstood and often confused with casual, permissive or reckless attitudes' (NHS Confederation, Citation2014b, p. 8).

Learning from experience

The third subtheme refers to the need for training and learning based on previous experience, including benefitting from good practice, and accepting that adverse outcomes might be inevitable, but learning from these events. Practitioners' access to recurrent training was a requirement for PRM across documents. The need for training to be updated regularly suggests recognition of the difficulties with one-off training. It also implied that PRM is complex, regardless of experience: 'All staff involved in risk management should receive relevant training which must be updated at least every three years' (NHS Confederation, Citation2014b, p. 11). As part of ongoing learning process, several documents noted the inevitability of negative outcomes and using these to facilitate learning. The Department of Health (Citation2009) guideline described the importance of learning from previous PRM use:

Things can go wrong even when best practice has been used. If things do go wrong or do not go according to plan, it is essential to learn why …. Learning from 'near misses' is vital to improving services, although not all lessons learned will require changes in practice (Department of Health, Citation2009, p. 33).

Discussion

This review aimed to identify how PRM is conceptualised and defined within national policies and guidelines. A further aim was to understand how, and in which contexts, policymakers justified PRM and the existing guidance on implementation. The current review contributes to the field of mental health risk management practice through the identification of three main themes: i) the conflicting aims of PRM, ii) conditional PRM, and iii) responsible PRM.

Documents defined PRM as a collaborative strengths-based approach that could aid, but also demonstrate recovery (theme one). Policymakers described the importance of empowering service users and collaborative care to support risk management, which has been supported by research (Damme et al., Citation2017; Wylie & Griffin, Citation2013). However, other documents advocated for clinicians to be more prescriptive in order to minimise risk. The results of the current review illustrate the challenges faced when balancing the different demands of positive risk management evident in policy and guidelines. The results can be considered alongside research showing that, despite the awareness of collaborative risk management, practitioners struggle to manage this balance, which often results in clinician-led working (Bowers, Citation2011; Just et al., Citation2021; Prokešová et al., Citation2016). This conflict has been described as 'caring in the context of risk' (Gale et al., Citation2016), which can leave practitioners feeling uncertain (Morgan & Andrews, Citation2016).

Theme two, Conditional PRM, concerned the tension between who, when and how PRM should be utilised. Despite a wealth of research available on risk and protective factors (Fox et al., Citation2015; O’Shea & Dickens, Citation2015; Taylor et al., Citation2015), there was little agreement on who was suitable for PRM and which clinicians should hold responsibility for possible outcomes. Several policies described categorising patient’s risk into suitable/not suitable, high/low categories, but this may be problematic (Logan et al., Citation2011). Clifford (Citation2011) has suggested that PRM categorisation needs to extend further than simply relying on underlying risk factors to determine risk categorisation, as this often misses the importance of contextual information in which risk increases/decreases. The current research was unable to discern why the wealth of research into risk and protective factors had not been adequately reflected in the reviewed documents. However, policies and guidelines are often a reflection of the current social and political context and may therefore not be an accurate reflection of up to date evidence and research.

Documents indicated that PRM implementation is dependent on the practitioner's awareness of the influences on their decision-making process, as well as service users' levels of risk and insight. One drawback of this approach is that a lack of insight may be assigned when service users disagree with clinicians’ decisions (Hamilton & Roper, Citation2006). This was in contrast with the recommendation that service users have the right to risk and make decisions even if clinicians do not agree with them. Hamilton and Roper (Citation2006) argue that insight should be a subjective experience born out of diverse contexts and that practitioners need to move towards seeing insight as a perception that could provide understanding into their work, culture and self.

Theme three, Responsible PRM, refers to the requirements that lead to best practice in PRM, illustrating the importance of knowing oneself and building good relationships with service users. Having an awareness of the factors that might influence clinicians’ own risk understanding, such as their current knowledge base, beliefs and attitudes, and relationship with service users, was also deemed important. A recent systematic review (Deering et al., Citation2019) supports the centrality of building relationships for effective risk management and that service users value interpersonal relationships, feeling heard and being included in the process, which may be important for future PRM recommendations.

Conflict and contradiction were evident throughout the themes. For example, policymakers struggled to specify who PRM was suitable for, on the one hand suggesting that it applied to all service users under all circumstances, whilst at others describing how PRM was only suitable to service users presenting with lower levels of risk. Such varied conceptualisations of risk management might hamper implementation and result in varied and unstandardised approaches to care (Reddington, Citation2017), with poorly understood recovery-focused risk management strategies (Mccabe et al., Citation2018). In worst-case scenarios, it might result in tokenistic and potentially harmful practices (Boardman & Roberts, Citation2014).

Research has indicated that clinicians were mainly unfamiliar with guidelines (Overmeer et al., Citation2005). Francke et al. (Citation2008) found that guideline adherence was generally low at around 27% with guidelines that were easily understood having a greater chance of being implemented. At the same time, awareness and familiarity with content increased chances of implementation. Logan et al. (Citation2011) highlight several challenges of guidelines themselves, stating the disagreement over recommendations as being one of the barriers to implementation. Additionally, due to policies and guidelines being a reflection of social and political contexts and not always an accurate reflection of evidence-based practice, practitioners may disagree with documents ultimately leading to long-term low adherence. This might be true of PRM where definitions differed across documents, policymakers, and organisations.

The themes and their sub-themes demonstrate the complexity of PRM, which was often interpreted differently by the makers of policies and guidelines, making it challenging to know when this approach should be utilised and how to achieve the appropriate balance between risk taking and risk management. This review strengthens previous research which has highlighted the challenges in understanding PRM (Drennan et al., Citation2014; Just et al., Citation2021; Logan et al., Citation2011; Overmeer et al., Citation2005; Reddington, Citation2017). It suggests that policies and guidelines are not consistent, explicit or detailed enough, which should be addressed in future documents (Seale et al., Citation2013).

Limitations

The current policy review pertained to national documents and local policy may better contain specific implementation guidance tailored to the particular context. Within qualitative analysis, the data analyst's subjectivity shapes the creation of understanding and meaning. Thus, the authors’ perceptions and beliefs likely influenced the findings. Braun et al. (Citation2019) argued that subjectivity is a resource that should be prioritised and not minimised. The credibility of the findings was enhanced through the discussion of codes and themes with the research team as well as the use of quotes to illustrate the interpretative findings.

As the current review was restricted to UK policies and guidelines, it is limited in its applicability to other geographical regions. However, the use of PRM is not limited to the UK and other regions with similar social, economic and mental health contexts may have similar challenges. It would therefore be helpful for future research to consider other geographical regions to consider overarching similarities and differences.

Clinical implications

It is unclear how the discrepancies between national policies and guidelines translate into the practical operationalisation of PRM and it would be helpful for future research to consider this area. However, it is clear that there are discrepancies within documents with further agreement on a national level being required to ensure that policies and guidelines provide a consistent and coherent message to frontline staff.

The results indicate that documents consistently identify the need to consider the suitability of PRM and the relationships that staff have with themselves and service users. Furthermore, documents advocate for risk assessments to consider underlying and contextual factors to ensure that staff do not unfairly limit PRM to specific service users and circumstances. Findings echo previous research of relational risk management and therefore emphasise the need for practitioners to prioritise a therapeutic relationship. Lastly, the documents point towards services creating the right environment in which staff can cultivate a reflexive relationship with themselves.

In conclusion, the systematic review and analysis illustrates how PRM is conceptualised and operationalised in policy and clinical guidelines. The identified documents did provide some guidance; however, they often presented conflicting ideas and definitions of PRM. Documents described PRM use as being influenced by service user and practitioner factors. Implementation was dependant on understanding service users' rights, having the required competencies and being reliant on relational security. Future policies and guidelines should, therefore, focus on providing consistent, detailed and clear recommendations on PRM.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used for this paper were policies and clinical guidelines and are freely available online (see references).

References

- Bellefontaine, S., & Lee, C. (2014). Between black and white: Examining grey literature in meta-analyses of psychological research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(8), 1378–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9795-1

- Boardman, J., Roberts, G. (2014). Risk, safety and recovery. https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/risk-safety-and-recovery

- Bowers, A. (2011). Clinical risk assessment and management of service users. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 16(3), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777271111153822

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health and social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer.

- British Psychological Society. (2006). Risk assessment and management. https://shop.bps.org.uk/risk-assessment-and-management-dcp-occasional-briefing-paper-no-4-november-2006.html

- Buse, K., Mays, N., Walt, G. (2005). Making health policy. Open University Press. http://search.proquest.com/docview/37212615/.

- Carthey, J., Walker, S., Deelchand, V., Vincent, C., & Griffiths, W. H. (2011). Breaking the rukes: Understanding non-complicance with policies and guidelines. BMJ, 343(sep13 3), d5283–d5283. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5283

- Centre for Workforce Intelligence. (2013). Creating a more integrated healthcare workforce. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/creating-a-more-integrated-healthcare-workforce

- Clifford, P. (2011). Evidence and principles for positive risk management. In C. Logan & R. Whittington (Eds.), Self-harm and violence. Towards best practice in managing risk in mental health services (pp. 205–214). John Wiley & Sons.

- Coffey, M., Cohen, R., Faulkner, A., Hannigan, B., Simpson, A., & Barlow, S. (2017). Ordinary risks and accepted fictions: How contrasting and competing priorities work in risk assessment and mental health care planning. Health Expectations, 20(3), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12474

- Coffey, M., Hannigan, B., Barlow, S., Cartwright, M., Cohen, R., Faulkner, A., Jones, A., & Simpson, A. (2019). Recovery-focused mental health care planning and co-ordination in acute inpatient mental health settings: A cross national comparative mixed methods study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2094-7

- Corey, J., O’Donoghue, S., Kelly, V., Mackinson, L., Williams, D., O’Reilly, K., & DeSanto-Madeya, S. (2018). Adoption of an electronic template to promote evidence-based practice for policies, proecdures, guidelines, and directives document. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 37(4), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000305

- Crichton, P., Carel, H., & Kidd, J. J. (2017). Epistemic injustice in psychiatry. BJPsych Bulletin, 41(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.115.050682

- Damme, L., Fortune, C., Vandevelde, S., & Vanderplasschen, W. (2017). The good lives model among detained female adolescents. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.002

- Deering, K., Pawson, C., Summers, N., & Williams, J. (2019). Patient perspectives of helpful risk management practices within mental health services: A mixed studies systematic review of primary research. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26(5–6), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12521

- Department of Health (2015). Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) in social work: Learning resources. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/learning-resources-mental-capacity-act-2005-mca-in-social-work

- Department of Health. (2016). Forensic mental health social work: Capabilities framework. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/forensic-mental-health-social-work-capabilities-framework

- Department of Health. (2009). Best practice in managing risk: Principles and evidence for best practice in the assessment and management of risk to self and others in mental health services. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-and-managing-risk-in-mental-health-services

- Department of Health. (2010). Good practice guidance on the assessment and management of risk in mental health and learning disability services. https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/promoting-quality-care-good-practice-guidance-assessment-and-management-risk-mental

- Department of Health & Social Care. (2019). Strengths-based social work: Practice framework and handbook. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/strengths-based-social-work-practice-framework-and-handbook

- Drennan, G., Wooldridge, J., Aiyegbusi, A., Alred, D., Ayres, J., Barker, R., Carr, S., Eunson, H., Lomas, H., Moore, E., Stanton, D., Shepherd, G. (2014). Making recovery a reality in forensic settings. https://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/2014/09/making-recovery-a-reality-in-forensic-settings

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401

- Fox, K. R., Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Kleiman, E. M., Bentley, K. H., & Nock, M. K. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002

- Francke, A. L., Smit, M. C., Je de Veer, A., & Mistiaen, P. (2008). Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 8(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-8-38

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowledge. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

- Gale, N. K., Thomas, G. M., Thwaites, R., Greenfield, S., & Brown, P. (2016). Towards a sociology of risk work: A narrative review and synthesis. Sociology Compass, 10(11), 1046–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12416

- Hall, S., & Duperouzel, H. (2011). We know about our risk, so we should be asked.” A tool to support service user involvement in the risk assessment process in forensic services for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 2(3), 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/20420921111186598

- Hamilton, B., & Roper, C. (2006). Troubling ‘insights’: Power and possibilities in mental health care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(4), 416–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00997.x

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. (2004). Working with older people towards prevention and early detection of depression best practice statement. http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/previous_resources/best_practice_statement/working_with_older_people.aspx

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. (2009). Admissions to adult mental health inpatient services best practice statement. http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/previous_resources/best_practice_statement/mental_health_inpatient_bps.aspx

- Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health. (2013). Guidance for commissioners of mental health services for people with learning disabilities. https://www.jcpmh.info/resource/guidance-for-commissioners-of-mental-health-services-for-people-with-learning-disabilities/

- Just, D., Palmier-Claus, J. E., & Tai, S. (2021). Positive risk management: Staff perspectives in acute mental health inpatient settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(4), 1899–1910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14752

- Kredo, T., Bernhardsson, S., Machingaidze, S., Young, T., Louw, Q., Ochodo, E., & Grimmer, K. (2016). Guide to clinical practice guidelines: The current state of play. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 28(1), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv115

- Langan, J., & Lindow, V. (2004). Living with risk: Mental health service user involvement in risk assessment and management. The Policy Press.

- Logan, C., Nathan, R., & Brown, A. (2011). Formulation in clinical risk assessment and management. In C. Logan & R. Whittington (Eds.), Self-harm and violence. Towards best practice in managing risk in mental health services (pp. 187–204). John Wiley & Sons.

- Logan, C., Nedopil, N., & Wolf, T. (2011). Guidelines and standards for managing risk in mental health services. In C. Logan & R. Whittington (Eds.), Self-harm and violence. Towards best practice in managing risk in mental health services (pp. 145–162). John Wiley & Sons.

- Mccabe, R., Whittington, R., Cramond, L., & Perkins, E. (2018). Contested understandings of recovery in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 27(5), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466037

- Meats, E., Brassey, J., Heneghan, C., & Glasziou, P. (2007). Using the turning research into practice (TRIP) database: How do clinicians really search? Journal of the Medical Library Association, 95(2), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.95.2.156

- Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. (2011). Consenting adults? Guidance for professionals and carers when considering rights and risks in sexual relationships involving people with a mental disorder. https://www.mwcscot.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/updated_consenting_adults.pdf

- Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. (2016). Supported decision making. https://www.mwcscot.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/mwc_sdm_draft_gp_guide_10__post_board__jw_final.pdf

- Morgan, S., & Andrews, N. (2016). Positive risk-taking: From rhetoric to reality. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(2), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2015-0045

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Intermediate care including reablement: Guidance (NG74). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng74

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2018). People's experience in adult social care services: Improving the experience of care and support for people using adult social care services: Guidance (NG86). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng86

- NHS Clinical Commissioners. (2016). Guidance for commissioners of psychiatric intensive care units (PICU). https://napicu.org.uk/guidance-for-commissioners-of-psychiatric-intensive-care-units-picu-2016/

- NHS Confederation. (2014a). Making recovery a reality in forensic settings. https://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/2014/09/making-recovery-a-reality-in-forensic-settings

- NHS Confederation. (2014b). Risk, safety and recovery. https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/risk-safety-and-recovery

- NHS England. (2013). High secure mental health services (Adult). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/c02-high-sec-mh.pdf

- O’Shea, L., & Dickens, G. (2015). Contribution of protective factors assessment to risk prediction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 30(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(15)30171-1

- Overmeer, T., Linton, S. J., Holmquist, L., Eriksson, M., & Engfeldt, P. (2005). Do evidence-based guidelines have an impact in primary care? A cross-sectional study of swedish physicians and physiotherapists. Spine, 30(1), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200501010-00024

- Prokešová, R., Brabcová, I., Pokojová, R., & Bártlová, S. (2016). Risk management in inpatient units in the czech republic from the point of view of nurses in leadership positions. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 37(2), 39–45.

- Reddington, G. (2017). The case for positive risk-taking to promote recovery. Mental Health Practice, 20(7), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.2017.e1183

- Robertson, J. P., & Collinson, C. (2011). Positive risk taking: Whose risk is it? An exploration in community outreach teams in adult mental health and learning disability services. Health, Risk & Society, 13(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2011.556185

- Royal College of Nursing. (2017). Three steps to positive practice. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-006075

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists. (2017). Occupational therapists' use of occupation-focused practice in secure hospitals: Practice guideline. https://www.rcot.co.uk/practice-resources/rcot-practice-guidelines/secure-hospitals

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2007). CR144: Challenging behaviour: A unified approach. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr144.pdf?sfvrsn=73e437e8_2

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2009). CR154: Good psychiatric practice (3rd ed.). https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr154.pdf?sfvrsn=e196928b_2

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2016). CR201: Rethinking risk to others in mental health services. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr201.pdf?sfvrsn=2b83d227_2

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2018). CR214: Personality disorder in Scotland: Raising awareness, raising expectations, raising hope. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/campaigning-for-better-mental-health-policy/college-reports/2018-college-reports/personality-disorder-in-scotland-raising-awareness-raising-expectations-raising-hope-cr214-aug-2018

- Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. (2009). Implementing recovery: A new framework for organisational change. http://yavee1czwq2ianky1a2ws010-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/implementing_recovery_paper.pdf

- Seale, J., Nind, M., & Simmons, B. (2013). Transforming positive-risk taking practices: The possibilities of creativity and resilience in learning disability contexts. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 15(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2012.703967

- Skills for Care & Skills for Health. (2014). A positive and proactive workforce: A guide to workforce development for commissioners and employers seeking to minimise the use of restrictive practices in social care and health. https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Document-library/Skills/Restrictive-practices/A-positive-and-proactive-workforce-WEB.pdf.

- Tannenbaum, S. J. (2005). Evidence-based practice as mental health policy: Three controversies and a caveat. Health Affairs, 24(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.163

- Taylor, P. J., Hutton, P., & Wood, L. (2015). Are people at risk of psychosis also at risk of suicide and self-harm? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 911–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002074

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Timmermans, S., & Mauck, A. (2005). The promise and pitfalls of evidence-based medicine. Health Affairs, 24(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.18

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- Walker, E. W. (2000). Policy analysis: A systematic approach to supporting policymaking in the public sector. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 9(1–3), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1360(200001/05)9:1/3 < 11::AID-MCDA264 > 3.0.CO2-3

- Wylie, L. A., & Griffin, H. L. (2013). G-map’s application of the good lives model to adolescent males who sexually harm: A case study. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 19(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2011.650715