Abstract

Background

Persistent feelings of emptiness, while poorly understood, characterise a range of mental health difficulties.

Aims

To investigate the meaning of emptiness from the perspective of those with lived experience.

Method

240 participants detailed their experiences of emptiness in a survey. Inductive thematic analysis was performed to produce a detailed description of emptiness and a definition of its typical manifestation. In a follow up survey, 178 individuals with lived experience of emptiness rated the accuracy of this definition.

Results

Nine components of emptiness were identified. These were used to produce a definition of the typical manifestation of emptiness, which highlighted a sense of going through life mechanically, purposelessly and numbly, with a psychological and bodily felt inner void, together with a sense of disconnectedness from others, and of not contributing to an unchanged but distant and remote world. Participants in the second survey judged this definition as highly accurate.

Conclusions

First person accounts of emptiness point to an integrated experience concerning the relationship between the self, others, and the external world more generally. Therefore, emptiness can be conceptualised as an existential feeling; a background orientation structuring the way in which the self relates to the interpersonal and impersonal world.

Introduction

Among the individual diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) within the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), chronic sense of emptiness appears to be especially pervasive. However, feelings of emptiness are also associated with anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., Citation2016; Klonsky, Citation2008), as well as being often reported by patients experiencing psychosis (Federn, Citation1952; Zandersen & Parnas, Citation2019). Reported feelings of emptiness also appear to be especially persistent. Zanarini and colleagues followed the symptom progression of individuals diagnosed with BPD over a decade, finding that the majority of symptoms typically remitted within a period of eight years, while sense of emptiness was still present after ten years (Zanarini et al., Citation2007). Qualitative reports also speak of the persistent nature of emptiness as a manifestation of long-term psychological distress present for individuals experiencing a range of mental health difficulties. Reflecting on her own experiences with schizophrenia, Kean reported that emptiness was a permanent feeling, which no drug or therapy was able to relieve (Kean, Citation2009). However, in spite of these pervasive and persistent characteristics, and its presence within commonly utilised diagnostic manuals, this sense of emptiness is under-researched and poorly understood (D’Agostino et al., Citation2020; Miller et al., Citation2020). The existing literature has speculated about the psychological mechanisms which may lead to a sense of emptiness. For instance, cognitive-behavioural clinicians have proposed that emptiness results from the necessity to detach from negative emotions that one is unable to control (Young et al., Citation2003), whilst psychoanalytically oriented authors see emptiness as the consequences of difficulties inherent to the relationship of the self with the world of inner objects (Kernberg, Citation1975). However, somewhat ironically, little effort has been made to provide a detailed description of “what it is like” to feel empty. As a consequence, researchers have repeatedly called for studies aimed at investigating and elucidating the features of this experience (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., Citation2016). Only once a thorough description has been achieved can one determine whether this experience is unique to specific mental health difficulties, and start to then speculate over causal mechanisms and begin considering strategies for treatment (Parnas et al., Citation2013; Stanghellini & Broome, Citation2014).

In response to this, the aim of this study is to provide a rigorous, detailed, and in-depth description of emptiness. In doing so, we follow recommendations from the phenomenological approach to psychopathology originally set out by Jaspers (Jaspers, Citation1963, Citation1968). Specifically, according to this approach a precise description of an experience is best achieved by exploring first-person accounts. Any description should be based on the subjective report of the patient, on a person’s lived experience (Broome et al., Citation2012). In addition, this approach is not content with the mere description of idiosyncratic experiences. Instead, its aim is to capture the general aspects of the phenomenon, to identify its typical features (Jaspers, Citation1963; Schwartz & Wiggins, Citation1987). As explained by Stanghellini and Ballerini: “trans-personal constructs, to be useful for psychopathological research, must be central exemplars of a wide range of personal narratives. They are prototypes – the best exemplars of a class” (Stanghellini & Ballerini, Citation2008). Thus, consistent with the Jaspersian phenomenological psychiatric tradition, in this paper we pursue a detailed description of emptiness informed by a wide range of reports from those with lived experience, with the ultimate goal of capturing the typical presentation of emptiness to consciousness.

Role of funding source

This research was funded internally by the University of Dundee.

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving subjects were approved by The University of Dundee School of Social Sciences Ethics Committee (Ref No. UoD-SoSS-PSY-STAFF-2018-49, SREC SS-31-2018).

Study 1

Methods

Participants and procedures

Due to the lack of clarity as to whether emptiness represents an experience unique to any specific diagnoses, the decision was made to include participants with and without a mental health diagnosis. Individuals aged 18 and over “who had ever felt empty” were invited to take part by completing an anonymous questionnaire hosted by the Online Surveys platform, which was accessed by a shared link. The questionnaire was made available online for two weeks. The study was advertised on social media, mental health forums, and university institution pages online. This was to give a wide pool of individuals the opportunity to take part in the study. All participants were made aware of the study purpose prior to providing consent.

Participants were asked to report their gender, age, nationality, education level, and employment status. Additionally, they were asked if they had ever received a mental health diagnosis from a health professional and, if so, to disclose these. Participants were also asked if they had ever thought about or attempted suicide. However, concerning these two questions they could also select “prefer not to say.” Participants were then asked seven questions relating to experiences of emptiness. No definition of emptiness was provided, in order to gather data that was as free as possible from theoretical or third-person influence. The first two questions asked how often the participant had felt empty respectively in their life and over the last month. There were four response options: “never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “all the time.” Subsequently, participants were asked five open-ended questions related to their own personal experience of feeling empty. They were encouraged to use their own words and express their answers in any way they saw fit. No word or character limit was imposed. The first of these questions asked: “What does it mean to you to feel empty?” This paper focuses on answers to this specific question, with analysis of further questions ongoing. (See Supplementary Appendix 1 for all open-ended questions).

As observed by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2013), the use of an open-ended online survey is ideally suited to sensitive topics because it offers privacy and anonymity to participants. Therefore, participants may be more willing to express themselves freely when not facing an interviewer, providing opportunity for the disclosure of personal emotional experiences. In addition, because we expected emptiness to have multiple components, this allowed for the collection of a large sample of self-reports, ensuring that all possible components could be identified.

Two-hundred-forty-nine individuals returned a completed questionnaire. Of this sample, nine were excluded due to never having felt empty. This resulted in a total sample of 240 completed questionnaires from individuals with self-reported lived experience of emptiness. includes details of demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. (See Supplementary Appendix 2 for demographic and diagnostic details by gender).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of sample in Study 1 (N = 240).

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v23 statistical package. We calculated descriptive statistics concerning demographic variables, frequency of emptiness feelings, number of diagnoses disclosed, and suicidal behaviour. We also assessed the level of association between the frequency of emptiness feelings and suicidal behaviour, using cross-tabulations and chi-square tests. For this analysis, we collapsed those who had felt empty “often” and “all the time” into a single category. This was done because only a small number of participants selected “all the time”; allocating these participants to a category of their own would have implied a very low expected frequency, impacting the capacity to undertake chi-square tests.

Concerning analysis of the open text responses about the participant’s own experience of emptiness, our procedure was in line with the principles and objectives of the phenomenological approach to psychopathology highlighted above. Specifically, we used inductive (i.e., data-driven) thematic analysis, with a focus on the semantic (i.e., explicit) rather than latent (i.e., implicit) level of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This began with reading all responses in order to familiarise with the data and form a global idea of their nature. Subsequently, we looked for the basic elements of the reported experiences in order to generate initial codes. Then we identified themes by sorting and collating the initial codes. Finally, and crucially, we drew from the themes to produce a summary statement aimed at capturing the typical presentation of the experience of emptiness as faithfully as possible. All analyses were conducted manually, to facilitate full immersion in the data. Only after completing the analyses was the data entered into NVivo 12 software. This was done to group together the extracts pertaining to each single theme, thereby aiding the reporting of the findings.

In recognition of the potential for the authors’ own contexts to influence interpretation of the research, bracketing was undertaken, and is provided as Supplementary Appendix 3.

Results

Statistical analyses

We found that suicide had been attempted by 24 (27.0%) of those who had felt empty often/all the time, compared to 11 (7.6%) of those who had felt empty sometimes: χ2(1)=16.10; Cramer’s V = 0.26; 95% BCa CI = 0.14 to 0.39; p = 0.001. Additionally, 72 (79.1%) of those who had felt empty often/all the time had thought about suicide, compared to 63 (45.3%) of those who had felt empty sometimes: χ2(1)=25.91; Cramer’s V = 0.34; 95% BCa CI= 0.22 to 0.45; p < 0.001.

Qualitative analysis

The total length of responses to the open-ended question about the subjective meaning of emptiness ranged from 1 to 169 words (M = 32.7, SD= 32.1). Thematic analysis of these responses revealed nine themes – which can be seen as the constituting components of the lived-experience of emptiness – pertaining to three existential domains. Five components concerned the affective, agentic and bodily aspects of the self, three related to the relationship between self and others, and one regarded the relationship between self and the external world more generally. Components and existential domains are outlined in the Panel (), with extracts to provide illustration of each.

Table 2. Existential domains, constituting components, and illustrative excerpts from the data.

Affective, agentic and bodily self

Emotional life and one’s sense of personal agency and physical body appeared disrupted in our participants. They reported being drained and soulless, experiencing a distressing “feeling of having no feelings.” They felt emotionally numb, unable to cry or laugh, to experience joy or sorrow, with some emphasising the difference between this feeling and those, such as sadness and despair, more commonly associated with low mood or depressive states. Similarly, participants described a lack of felt purpose and meaning in life, with everything appearing pointless. They reported having “nothing valuable to work towards,” being unable to engage with any meaningful activity, “wanting nothing,” and therefore lacking a sense of having a direction in life. This was associated with a sense of “just going through the motions,” or “running on autopilot.” Participants described themselves as automatons carrying out tasks necessary for survival but with little or no conscious connection to these activities. Absence of emotions and purpose were reported as being at the roots of a sense of being empty inside. Participants tried to convey this feeling through analogies and metaphors. They described themselves as being like “a blank page with no way of writing it,” an “empty shell,” a “cover that doesn’t have anything inside,” or a “bottomless jug,” with the latter highlighting that any fleeting emotional experiences would “pass right through,” thereby making it impossible for the inner void to ever be filled. These psychological feelings could be accompanied by uncomfortable sensations (e.g., an ache, a dull pain, a knot, a sense of hollowness) in the body, often within the chest, or central cavities of the body.

Self and others

Emptiness was typically experienced with reference to one’s relationship to other people. Firstly, participants felt that they had nothing to give to others. They felt unable to make an impact, to give any real contribution to their personal relationships and communal life. Relatedly, they expressed a sense of worthlessness and a lack of inherent value, and depicted themselves as being a nuisance and a burden to others. Additionally, participants experienced a lack of recognition. They felt as if they were “invisible” to those around them. They felt that they were neither listened to nor noticed by others, including those one cared the most about, that they were a “missing person” despite being surrounded by others. This was associated with the sense of being objectified and expendable (e.g., treated like a “doormat,” a “tool”). Participants also spoke of feeling alone, disconnected, cut off and distant from those around them. In general, components concerning this domain highlight a keenly felt sense of isolation and utter loneliness, an inability to connect, to join in, to be seen, and to be an integral part of the social world.

Self and external world

Emptiness also concerned a specific way for the self to relate to the external world more generally, including the impersonal world. Participants reported feeling detached, far away from everything, experiencing a sense of “othering.” This aspect of emptiness was metaphorically represented in terms of either a barrier (e.g., a fog, a veil) or a distance (e.g., a chasm, a gulf) between self and world. The world was described as being the same as always, as retaining its “brightness,” as being a place full of life, but no longer as something one could engage with. To convey this feeling, one participant referred to Samuel Coleridge’s verses “water, water everywhere/nor any drop to drink,” from the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. However, while being disconnected from the world, the self does not cease to exist. But this is mere existence, which was expressed by one participant as “just taking up space and using up oxygen.”

These identified components were used to create a definition of emptiness representing its prototypical manifestation. This was as follows: A feeling that one is going through life mechanically, devoid of emotions and purpose, and therefore is empty inside, with emptiness often being bodily felt in the form of a discomfort in the chest. This is coupled with feelings that one is disconnected from others, in some way invisible to others, and unable to contribute to a world that remains the same, but from which one is distant and detached. It is important to emphasize that this definition refers to an ideal type, a prototype. Our assumption is that idiosyncratic experiences of emptiness tend to gravitate towards this prototype.

Study 2

The aim of Study 2 was to test the accuracy of the definition of emptiness produced in Study 1, by submitting it to the scrutiny of individuals with lived experience and evoking their feedback. Given that our definition intended to encapsulate the typical manifestation of emptiness, we saw individuals with lived experience of emptiness as the best judges of the validity of such definition.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participant recruitment followed the same procedure as Study 1. Following ethical approval, the survey was advertised using online platforms for two weeks via a shared link. All individuals over 18 who had experienced emptiness could participate, including those who had already participated in Study 1.

As in Study 1, participants were asked demographic questions, and how often they had felt empty in their whole life and in the previous month. They were also asked whether they had completed the initial survey. Then participants were provided with the proposed definition noted above and asked to indicate how closely this aligned their own experiences of emptiness, by rating its accuracy using a numerical rating scale ranging from 1 to 10, with anchors describing accuracy extremes (1 = not at all accurate; 10 = extremely accurate). (Two additional rating criteria were also used but are not discussed here: See Supplementary Appendix 4 for details). Participants were then encouraged to provide any comments related to the definition in an open text box with no imposed word limit.

One-hundred-eighty-eight individuals completed the online survey. Of this 10 were excluded due to reporting never having felt empty. Of the resulting 178 participants, 17.5% reported having contributed to Study 1. Demographically, the sample was similar to that of the previous study (see for details).

Table 3. Demographic information relating to the sample for Study 2 (N = 178).

Analyses

We used SPSS v23 statistical package to calculate descriptive statistics concerning demographic variables, frequency of emptiness feelings, and the rated accuracy of the definition of emptiness. We then looked at the accuracy ratings separately for those who had felt empty sometimes and those who had felt empty often/all the times in life, and we compared ratings within these two subgroups using t-test.

Results

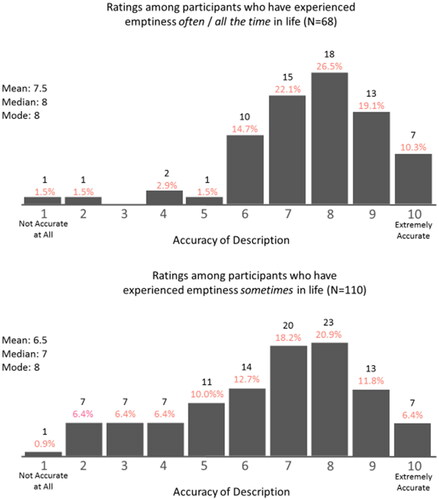

Overall, participants rated the definition of emptiness as being fairly accurate: mean = 6.9, SD = 2.1; median = 7, mode = 8. However, we found that those who had felt empty often/all the times rated the definition as more accurate than those who had felt empty sometimes: mean = 7.5, SD = 1.8 and mean = 6.5, SD = 2.3 respectively; t(176) = 3.24, p = 0.001. Noticeably, almost 93% of participants who had felt empty often/all the times gave a score included between 6 and 10, compared to 71% of those who had felt empty sometimes. Details of the two distributions can be found in . (We performed the same analyses excluding those who had also participated in Study 1, and results were virtually the same).

. Distribution of ratings about the accuracy of description of the proposed definition of “emptiness.”

Concerning participants’ comments about the definition, no participants expressed that any aspect of their experience was missing. However, some indicated that they did not feel emptiness physically in their body.

Discussion

The research we have presented confirmed that a sense of emptiness can be experienced by individuals with a variety of mental health diagnoses, as well as by individuals who have never been diagnosed with a mental health problem. Thus suggesting that emptiness is not a unique feature indicative of a personality disorder, as currently identified using the DSM-5. We also found that participants with more recurrent feelings of emptiness were more likely to report suicidal behaviour than participants with less recurrent feelings of emptiness. Importantly, we were able to define the way in which emptiness is typically experienced. Our analysis revealed that feeling empty implies a sense that one is going through life mechanically, purposelessly, and numbly, with a sense of an inner void that nothing can fill, which may also be experienced as bodily discomfort, especially in the chest. Concurrently, one has a sense of being in some way “invisible” to, and disconnected from other people, and of being unable to give a worthwhile contribution to a world that, while retaining its usual features, appears distant and remote.

In the data gathered throughout these studies, emptiness was described in extremely uniform terms across participants, regardless of type or number of mental health diagnoses. A tentative conclusion from this finding is that emptiness can be understood as a transdiagnostic experience of distress, present across the spectrum of those with and without histories of mental health difficulties. While this study involved only a small number of participants who disclosed a diagnosis of a personality disorder, for whom emptiness would be expected to be most prominent, based on the uniformity of descriptions given by all participants, there is no suggestion that emptiness takes a distinctly different form or quality depending on a person’s diagnoses.

Additionally, analysis revealed that the presentation of emptiness described above is more typical of those experiencing emptiness often or all the time than of those who feel empty only sometimes. This could indicate that what is described hence constitutes an intense form of emptiness that applies particularly to those who experience emptiness chronically, perhaps because only in these people all the components have become coalesced over time. However, the fact that multiple components of emptiness are identifiable, and that certain components may be more or less prominent in different individuals, should not lead to the conclusion that emptiness is a collection of separate experiences. On the contrary, the nature of participants’ descriptions points to a unitary and integrated experience, to an inextricable interconnectedness of the various components.

As a unitary feeling concerning the self and its relation to other people and the impersonal world, sense of emptiness can be conceived as an existential feeling (Ratcliffe, Citation2009; Stephan, Citation2012). Existential feelings have been conceptualised as background orientations structuring the way in which the self relates to the interpersonal and impersonal world. They are ways of “finding oneself in the world” (Ratcliffe, Citation2005). Typically, one has a pre-reflective background feeling of being firmly grounded and immersed in a world as a field of practical activities and interactions with significant others, framed by shared beliefs, values and goals. This constitutes our taken-for-granted, unquestioned everyday reality. However, one may also have background feelings that markedly differ from the most usual ones. These feelings, which become conspicuous because of their unusual and baffling character, entail the experience of an altered sense of reality. Specifically concerning sense of emptiness, one’s background feeling concerns an impoverished and devitalised self, surrounded by people who are experienced as indifferent and distant, and facing an external world that is inaccessible and devoid of significance.

It is worthwhile stressing the distinctiveness of a sense of emptiness, in terms of the way in which one experiences both the self and the external world. The self is not experienced as either fragmented, inexistent, or merged with the environment, as it may be in psychotic experiences (Sass & Parnas, Citation2003), nor as an outside observer of one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, body or actions, as it may happen in depersonalisation (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The self may be a diminished and vacant self, characterised by a degree of inertia thereby lacking what Fuchs defines as the “seeking and striving” element of experience (Fuchs, Citation2005). But it is nonetheless an existing self, with its own boundaries and unique perspective. In fact, the boundaries of the self are so clearly delineated as to constitute a sort of prison, a “bubble” within which one is constrained, and which prevents one from connecting to others and the world. But note, however, that the way in which the outside world is experienced represents a further distinctive aspect of emptiness. This is a world in which other people go on with their usual business, a world that retains its vibrancy and dynamism. Therefore, in emptiness the world in not fragmented or chaotic, as in experiences diagnosed as schizophrenia, nor is it faked or dream-like, as in derealisation.

Obviously, this research is not without limitations, and further study should address these. First, being survey based, this research elicited relatively succinct accounts of first-person experiences of emptiness. Future research should aim at an in-depth exploration of phenomenological aspects of emptiness that emerge as important from our research, such as agency and embodiment, as well as aspects that are not touched upon by our participants but may be of relevance, such as temporality. Presumably, this could be achievable through the use of semi-structured interviews. Secondly, our research involved mainly British and Irish participants. Future research should seek ethnically diverse samples, to explore whether emptiness is culture-specific, or whether this represents a universally human experience. Third, we identified an important association between chronicity of sense of emptiness and suicidal behaviour, which is in line with existing literature (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., Citation2016). However, our research could not shed light on the nature of such relationship, or of the relevant mediating factors. Therefore, future work should aim to understand this link in the hope of contributing to suicide prevention strategy through identifying and intervening for those at high risk. A final important area for clarification following this research would be to further explore our suggestion that, emptiness is a transdiagnostic experience that does not vary in quality or form for those with differing diagnoses. Therefore, research aiming to assess emptiness in a diverse and verified clinical population, including those who have received a diagnosis of BPD, would help to determine the accuracy of this conclusion.

In conclusion, this paper details the first lived-experience informed research attempting to understand the phenomenology of emptiness. We hope that our findings will spark interest and debate throughout the clinical, psychiatric and philosophical research communities, about the nature of this common yet under-researched experience, as well as its implications for individuals and societies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (268.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Kind thanks are given to Dr Anna Bortolan, Dr Matthew Constantinou, and Jack Gilgunn for their time and comments in reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Fernández-Fernández, R., Colino, L., Fajardo, L., Perteguer-Barrio, R., & De Leon, J. (2016). The addictive model of self-harming (non-suicidal and suicidal) behavior. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 1, 7–8.

- Braun, G., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, G., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. SAGE.

- Broome, M. R., Owen, G. S., & Stringaris, A. (Eds.). (2012). The Maudsley reader in phenomenological psychiatry. Cambridge University Press.

- D’Agostino, A., Pepi, R., Rossi Monti, M., & Starcevic, V. (2020). The feeling of emptiness: A review of a complex subjective experience. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(5), 287–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000269

- Federn, P. (1952). Ego psychology and the psychoses. Basic Books.

- Fuchs, T. (2005). Corporealized and disembodied minds: A phenomenological view of the body in melancholia and schizophrenia. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 12, 95.

- Jaspers, K. (1963). General psychopathology (J. Hoenig & MW Hamilton, trans.). London: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Jaspers, K. (1968). The phenomenological approach in psychopathology. British Journal of Psychiatry, 114(516), 1313–1323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.114.516.1313

- Kean, C. (2009). Silencing the self: Schizophrenia as a self-disturbance. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(6), 1034–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp043

- Kernberg, O. (1975). The subjective experience of emptiness. In Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

- Klonsky, E. D. (2008). What is emptiness? Clarifying the 7th criterion for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(4), 418–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.418

- Miller, C. E., Townsend, M. L., Day, N. J. S., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2020). Measuring the shadows: A systematic review of chronic emptiness in borderline personality disorder. PLoS One, 15(7), e0233970. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233970

- Parnas, J., Sass, L. A., & Zahavi, D. (2013). Rediscovering psychopathology: The epistemology and phenomenology of the psychiatric object. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs153

- Ratcliffe, M. (2005). The feeling of being. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12, 43–60.

- Ratcliffe, M. (2009). Existential feeling and psychopathology. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 16, 179–194.

- Sass, L. A., & Parnas, J. (2003). Schizophrenia, consciousness, and the self. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(3), 427–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007017

- Schwartz, M. A., & Wiggins, O. P. (1987). Diagnosis and ideal types: A contribution to psychiatric classification. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28(4), 277–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(87)90064-2

- Stanghellini, G., & Ballerini, M. (2008). Qualitative analysis. Its use in psychopathological research. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(3), 161–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01139.x

- Stanghellini, G., & Broome, M. R. (2014). Psychopathology as the basic science of psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(3), 169–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138974

- Stephan, A. (2012). Emotions, existential feelings, and their regulation. Emotion Review, 4(2), 157–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073911430138

- Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy. Guilford.

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Reich, D. B., Silk, K. R., Hudson, J. I., & McSweeney, L. B. (2007). The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: A 10-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 929–935. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929

- Zandersen, M., & Parnas, J. (2019). Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and the boundaries of the schizophrenia spectrum. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx183