Abstract

Background

Remote therapy promises a cost-effective way of increasing delivery of psychological-therapy in underserved populations. However, research shows a “digital divide”, with some groups experiencing digital exclusion.

Aims

To assess whether technology, accessibility, and demographic factors influence remote therapy uptake among individuals with psychosis, and whether demographic factors are associated with digital exclusion.

Methods

Remote therapy uptake and demographics were assessed in people (n = 51) within a psychology-led service for psychosis, using a survey of access to digital hardware, data and private space.

Results

The majority of individuals had access to digital devices, but 29% did not meet minimum requirements for remote therapy. Nineteen (37%) individuals declined remote therapy. Those who accepted were significantly younger and more likely to have access to technology than those who declined. The mean age of those with access to smartphones and large screen devices was younger than those without access.

Conclusions

A subgroup of people with psychosis face barriers to remote therapy and a significant minority are digitally excluded. Older age is a key factor influencing remote therapy uptake, potentially related to less access to digital devices. Services must minimize exclusion through provision of training, hardware and data, whilst promoting individual choice.

Introduction

To prevent the spread of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), in March 2020 the UK government implemented social-distancing measures, restricting in-person interactions. As a result, mental health services were required to postpone in-person appointments, instead switching to remote assessment and delivery of psychological interventions. Recent research has shown that therapy that is delivered remotely, via telephone, video, or the internet can be as effective as in-person therapy (Acierno et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., Citation2008; Wagner et al., Citation2014). Remote therapy offers promise for a cost-effective way of increasing delivery of therapeutic interventions, improving access for underserved populations who find it difficult to attend in-person therapy and serving as a convenient alternative for others. Whilst early research into the effectiveness of remote therapies is promising, direct comparisons with in-person therapy are still scarce, and views of service users, carers and staff are mixed, with some concerned about being digitally excluded and the loss of a therapeutic “safe space” (Liberati et al., Citation2021). A recent review of the literature concluded that studies of the use of videoconferencing for severe mental illness are currently lacking (Thomas et al., Citation2021) and the impact of the shift toward remote intervention will inevitably be complex, with research needed to identify adverse effects as well as benefits.

Expanding access to digital services for effective care was included in the 2016 “Five Year Forward View of Mental Health” (NHS England, Citation2014), and in the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS, Citation2019). Access to internet-enabled technology such as smartphones, tablets, desktop computers and laptops, has shown exponential growth. Approximately, 82% of the UK adult population now own smartphones (Ofcom, Citation2020) and the percentage of adults who make video or voice calls over the internet has more than trebled over the past decade, to around 50% in 2019 (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019a). In February 2020 (prior to the introduction of government restrictions) weekly online voice, and video calls, were used by 54% and 35% of UK adults respectively, rising to 72% and 71%, respectively, after the introduction of social distancing measures, in April/May 2020 (Ofcom, Citation2020). However, there are concerns that increased adoption of remote therapy may disproportionately exclude some demographic groups, creating a “digital divide”. Those in contact with mental health services have been shown to be disproportionately affected by the digital divide (Dobransky & Hargittai, 2016; Tobitt & Percival, Citation2019). Identifying and minimizing digital exclusion is therefore essential if we are to ensure equitable delivery of healthcare interventions and the successful implementation of remote therapy.

Research has highlighted factors which can contribute to digital exclusion and present obstacles to the effective implementation of digital mental health interventions (Greer et al., Citation2019; Wykes & Brown, Citation2016). This work suggests the benefits of digital interventions are only achievable if service users have the access, ability, and confidence to engage with them, and that barriers related to mental health difficulties are addressed. This includes not only access to the hardware, internet, and the skills and confidence to navigate remote therapy, but also the ability to do so in a private space. In relation to psychosis, as with the general population, access to technologies has increased in recent years, with one US study conducted between 2014 and 2015 finding that 81.4% of their sample had access to mobile phones (Firth et al., Citation2016). Gay et al. (Citation2016) conducted a web-based survey of adults who self-identified as having a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (n = 457). They found that 90% of individuals had access to more than one internet-enabled device, and that many used these for a variety of reasons associated with their mental health (e.g. support from family and friends and identifying coping strategies). However, as this survey was conducted online only, it included only individuals who were already accessing the internet and is therefore highly likely to overestimate technology access for the population as a whole.

To date, there have been few studies of digital exclusion in psychosis, and none evaluating uptake of remote therapy in routine care. Ennis et al. (Citation2012) conducted a survey to examine digital exclusion in people diagnosed with severe mental illness, the majority of whom experienced psychosis, under the care of UK community mental health services. Participants (n = 121) were found to be at risk of digital exclusion, with older individuals and those from ethnic minority backgrounds at particularly high-risk. They also found that people from black and minority ethnic groups were more likely to access public internet devices rather than personal devices, and that individuals who had been unwell for longer periods were at higher risk of digital exclusion. This study was replicated five years later in a larger sample, to assess any changes in digital exclusion in the intervening period (Robotham et al., Citation2016). Participants with psychosis (n = 121) and depression (n = 120) were found to have lower rates of digital exclusion than five years previously, although 18.3% of individuals with psychosis remained digitally excluded. Additionally, people with psychosis also had less confidence in using the internet than those with depression. Those who were digitally excluded were generally older and had been in contact with services for longer. One key finding was that excluded participants stated that lack of knowledge was a barrier to digital use and that they most wanted to use the internet via a computer, rather than a mobile phone. The findings underscore the need for support and training when offering remote therapy, alongside access to preferred hardware.

Remote therapy for psychosis has not previously been offered as standard, but with changing practices due to COVID-19 (Shore et al., Citation2020; Zhou et al., Citation2020), it has been imperative for services to adapt the delivery of psychological interventions. This provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the uptake of remote therapy in routine clinical services and factors associated with uptake, in order to better understand and address digital exclusion during the pandemic and beyond. This study reports data from service users who had been referred to the Psychological Intervention Clinic for outpatients with Psychosis (PICuP), based at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM). The aims were to:

Assess uptake of remote therapy in PICuP during the first implementation of COVID-19 UK government restrictions and whether this was influenced by demographic factors.

Assess access to technology and whether this influenced remote therapy uptake and was related to demographic factors.

Examine reasons for declining remote therapy, including confidence and preference.

Material and methods

Service context

PICuP is a specialist psychology-led service within SLaM, offering cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and family interventions (FIs) for adults affected by psychosis and associated emotional difficulties (see Peters et al., Citation2015 for a description of population, service context and outcomes). Due to government restrictions owing to COVID-19, at the time of this audit the service was required to operate remotely, offering clients the option of either remote therapy or remaining on a waitlist until a return of in-person therapy.

Procedure

Data collection took place throughout April 2020 during UK government social-distancing measures. All service users currently on the PICuP caseload who had been offered remote therapy since the beginning of these COVID-19 government restrictions, were invited to complete a survey designed specifically for this study, exploring access, attitudes, and preferences regarding remote therapy. All individuals gave consent for their data to be used. To avoid including only those with access to digital technology, individuals were given the option of having a link to the survey sent to them via e-mail or a web-based application, or to complete the survey over telephone, with clinician support. Service users being seen for therapy were invited to complete the survey by their therapist, and those on the waiting list were contacted by AW and FK. As a service-related audit, ethical and external regulatory approvals were not required.

Fifty-one service users (of 81 on the current PICuP caseload) completed the survey. One client declined to complete the survey, and the remainder did not respond to contact by either telephone or e-mail. Completers had a mean age of 41.44 (SD = 12.80). Twenty-eight (55%) identified as female, and 23 (45%) as male. Fifty-five percent of those where data were available (ethnicity data missing, n = 6), identified as belonging to minority ethnic groups, which is representative of the PICuP service population (Peters et al., Citation2015). Further demographic data are included in Supplementary Materials.

Measures

Remote therapy survey

The questions in the survey were selected by authors AW, FK, HM and AH based on a review of the previous literature and team discussions with other clinical psychologists, trainee psychologists and a peer supporter. Digital exclusion has previously been defined as “lacking access to Internet technology” and “lacking confidence in using Internet technology” (Robotham et al., Citation2016). Questions therefore related to the following sections: hardware device access; fast enough internet access (as subjectively defined by the service user, “is your internet fast enough for reliable video chat?”); and privacy. For those who declined remote therapy, further questions asked participants to select reasons for declining: personal preference; monetary; lack of private space; lack of confidence; data privacy; access to technology; and unusual experiences or beliefs. Each person was also asked if they would take up remote therapy if there were no practical barriers.

Demographics

Demographic data were collected for all service users who completed the survey from the SLaM electronic patient journey system (EPJS), including age, gender and ethnicity. EPJS uses the official United Kingdom classification of ethnicity (Office for National Statistics, Citationn.d.).

Data analyses

Variables relating to access to digital therapy are reported using descriptive statistics. For technology access, survey responses were combined to categorize minimum requirements for video therapy (video device and internet), preferable requirements (large screen device and internet) and optimal requirements (large screen device, internet and private space). Demographics of those who accepted the offer of remote therapy were compared with those who rejected remote therapy using chi-square tests for variables categorized dichotomously (gender and ethnicity) and t-tests for continuous variables (age). Demographics of those with and without (yes vs. no) access to technology, confidence and access to private space were also compared on demographic variables using chi-square tests. Reasons for declining remote therapy were reported using descriptive statistics. The largest ethnic group in the UK is white/white British. Due to the sample size, for analysis those who were identified as belonging to ethnic minority groups were grouped collectively, for comparison with those classified as white/white British.

Results

Aim 1 – uptake of remote therapy

Sixty-three percent of the sample accepted, and 37% declined, the offer of remote therapy. Service users who accepted remote therapy were significantly younger (mean age: 38) than those who declined remote therapy (mean age: 47.05). There was no significant difference between groups on gender or ethnicity (see ).

Table 1. Demographics comparison of remote therapy uptake.

Aim 2 – access to technology and influence on therapy uptake

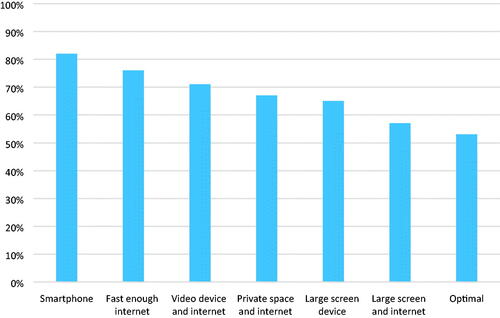

shows the proportion of those with access to technology and private space. In total, 82% (n = 42) had a smartphone, 76% (n = 39) of individuals had fast enough internet 71% (n = 36) had a video device and internet (minimum requirements), 67% (n = 34) had access to a private space and internet 65% (n = 33) had access to a large screen device, and 57% (n = 29) had access to a preferable requirement of a large screen device and fast enough internet (n = 15). Only 53% (n = 27) of individuals had access to optimal setup of a large screen device internet and private space.

shows the proportion of those who had access to technology and private space for those who accepted and those who declined remote therapy, and chi-square comparisons between groups. Those who accepted were significantly more likely than those who declined to have access to fast enough internet and to a smartphone, as well as “video device and fast enough internet” and “large screen device and fast enough internet”.

Table 2. The percentage of those with access to technology, and comparison of therapy uptake.

shows the mean ages of those with access vs. those without access to devices, private space, internet and combinations of these. There were significant differences in mean ages for access to “video device and internet”, “large screen device and fast enough internet” and smartphone access.

Table 3. Access to technology: comparison by mean age.

There were no significant differences between men and women or between white and minority ethnic groups (see Supplementary Materials), in access to any device, internet, private space or combination of these.

Aim 3 – reasons for declining remote therapy

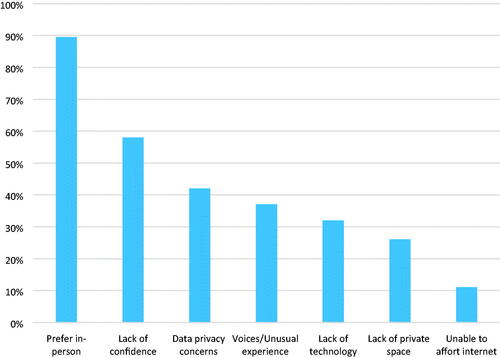

shows the reasons endorsed for declining remote therapy, as a percentage of those who declined therapy. The most common reason for declining remote therapy was a preference for in-person therapy, endorsed by 17 (89%) of those who declined therapy. Lack of confidence was endorsed by 11 (58%), data privacy concerns by 8 (42%), voices and unusual experiences or beliefs by 7 (37%), lack of technology by 6 (32%), lack of private space by 5 (26%) and being unable to afford the internet (11%).

Barriers to remote therapy

Six of those who declined remote therapy (32%) expressed that they would have opted for remote therapy if there were no practical barriers to them doing so. Three participants (16%) who previously refused remote therapy expressed that they had changed their mind within four weeks of it being offered and would now like to try it. The most common reason given was that the national social-distancing measures were likely to last longer than they had expected.

Discussion

This study reports several key findings. A substantial minority (37%) of the sample declined the offer of remote therapy. They were significantly older than those who accepted remote therapy but did not differ in gender or ethnicity. Overall, the majority of service users had access to technology and smartphone access was comparable to that of the general population and to other studies in those with psychosis (Firth et al., Citation2016). However, rates of internet access were lower than both the general population (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019a) and other psychosis studies (Firth et al., Citation2016), and a significant minority were digitally excluded. Twenty-one percent did not have fast enough internet for remote therapy and 35% did not have the minimum necessary digital requirements for video therapy (video device and fast enough internet). A third did not have access to private space. Fewer people had large screen devices than smartphones, and just under half (47%) of those who completed the survey did not meet our a-priori defined optimum set-up for remote therapy (large screen device, fast enough internet and private space). When comparing those who declined the offer of remote therapy with those who accepted it, there was a significant difference in those with “fast enough internet”, “smartphone access”, “video devices and fast enough internet” and “large screen devices and fast enough internet”, representing less access in the group who declined. This indicates that access to both hardware and fast enough internet may drive reasons behind individuals declining remote therapy. There was no difference between groups in access to private space in which to do remote therapy.

There were some demographic differences in access to devices, private space, and the internet. The average age of those who had access to “smartphones”, “large screen devices”, and “large screen devices and fast enough internet” was younger than those who did not. No differences in gender or ethnicity were found for access to digital technology.

When stating reasons for declining remote therapy, a high proportion stated that they would prefer in-person therapy, indicating that declining was not likely to be due to indifference about receiving therapy generally. In the context of COVID-19 restrictions, this decision was likely to be influenced by the individual’s perception of the duration of restrictions, and the option to wait for in-person therapy. Individual feedback from service users confirmed this to be the case and three individuals who originally declined, opted for remote therapy within four weeks, when it became apparent that restrictions would last longer than first expected. Declining remote therapy in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have included individual’s weighing up quicker access to remote therapy, with waiting for in-person therapy. Some individuals may have accepted remote therapy if this was the only option, but nevertheless, these responses show that, when given the option, some individuals show a preference for in-person therapy over remote-therapy. Lack of confidence in using remote therapy was the second most common reason given (58%) and data privacy concerns were also relatively common (42%). Lack of technology and private space was also endorsed as reasons by 32% and 26% of individuals who declined, respectively. Importantly, and more specific to individuals with psychosis, voices and unusual experiences or beliefs contributed to declining remote therapy for 37% of individuals. Taken together, these findings indicate that, as shown in a previous study (Robotham et al., Citation2016), the digital divide identified in mental health service users may be lessening, but that a divide may remain between older and younger individuals. The findings of this study indicate that older individuals may have less access to digital devices and internet, but reasons for declining remote therapy may also be the result of a lack of confidence in technology use.

Implications

Although those declining remote therapy were in the minority, this minority is large enough for it not to be viable to offer remote-only therapy services. It must be incumbent on services to ensure that interventions delivered digitally, increase access for underserved communities, rather than further marginalize individuals. Reasons for declining remote therapy are personal and improving access to remote therapy requires an individualized problem-solving approach. Age is a factor influencing uptake of remote therapy and reasons for age differences in uptake vs. decline need to be explored further. Access to digital technology may be a barrier in older age groups (Olphert & Damodaran, Citation2013; Robotham et al., Citation2016) and for those without access to hardware and internet, services should consider prioritizing in-person therapy. Services may consider offering provision of laptops/tablets to these individuals, and data packages can be negotiated to help those who do not have access to the internet. Whilst this may come at some expense to services, equitable access to mental health services is essential, and problem-solving at both team and management levels is necessary. Providing equipment alone, however, is not sufficient to address digital exclusion, and training in the use of devices will likely be necessary. There is a need to monitor changes in the digital divide as technology evolves. In the coming years, it is likely that age-related digital divide will lessen, as early digital users who are more familiar with the use of digital technologies become older. However, some digital divide in age may be maintained by factors, such as feelings of inadequacy in technology use compared to digital natives who have grown up with technology, as well as health-related barriers in older-adults, such as hearing and visual impairments (Vaportzis et al., Citation2017; Zhai, Citation2021).

A lack of confidence in using remote therapy is perhaps the most tractable of reasons for digital exclusion, and training and tutorials should be provided and offered as standard to help reduce this digital divide. This requires staff within teams to feel confident in using technology, and it should not be assumed that a digital divide is not also present for staff working within clinical services. It is important therefore that all staff are offered adequate support and training in using remote therapy, as well as provided support in helping clients who may want access to remote therapy but lack the confidence to do so (Hilty et al., Citation2019).

Access to private space is more difficult to address, and clients may be unable to accept remote therapy even if they have access to the necessary technology. Without private space, service users may feel unable to talk openly about their experiences. The need for confidentiality and privacy is a strong argument for the need for some provision of in-person therapy, with private space, for all services offering psychological interventions. Access to private space is likely to be related to socioeconomic status, such as poverty and unemployment, with those of lower socioeconomic status less likely to have access to private space, thus being further marginalized by unequal access to provision of remote therapy. It should be considered that in our sample, access to private space might be lower than in other geographical areas, due to London housing. Reassurances about data privacy are also required, particularly in a population, such as in this study, who may be prone to mistrust around data and privacy issues. Clinical teams and service trusts need to apply careful thought to which digital platforms they adopt, their data privacy policies, and their suitability for clinical use. This relies on an open communication around data privacy, which may help to alleviate some client concerns and allow them to make informed decisions. A possible solution for issues of privacy during the pandemic is for NHS trusts to provide COVID-safe physical spaces from which service users can access remote therapy. This might be possible via co-working with libraries and third sector organizations.

More specific to this population, some clients identified unusual experiences or belief as a reason for their reluctance for remote therapy. Understanding how these experiences may affect the individual in accessing remote therapy requires further qualitative research, and service user input on how these issues may be alleviated.

Intuitively, large-screen devices allow the client and therapist to see one another more clearly, with the assumption that this aids the therapeutic relationship and building of rapport. There is little research, however, into the optimum set-up for virtual therapy and group preferences, acceptability and efficacy for both clinicians and service users. It may be that some individuals prefer using smaller screen devices, and it should not be discounted that, for some, engagement and efficacy may be equally well facilitated with the use of non-video or smaller-screen devices. Furthermore, there should be the option for service users to decide and to change their minds about the method of intervention delivery. Increasing individual choice and autonomy, regardless of the method of delivery is empowering and important feature of person-centered care, which may increase engagement with services.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Although the sample was largely representative of the individuals seen by the team, a larger sample would allow for a bigger picture of the digital divide across the country. Due to the nature of the PICuP service, which does not provide an outreach service, it may represent a higher functioning subsample of the local population of people with psychosis. London has been shown to have the lowest rates of digital exclusion in the United Kingdom (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019b) and disparities in digital access may be more apparent in other regions.

Due to a lack of data, comparisons were not made based on socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is linked to material deprivation, social isolation, education, lack of access to private space, and poorer digital literacy, and is an additional demographic factor likely to be associated with a digital divide. Future studies should assess the contribution of sociodemographic status and education when evaluating and addressing digital exclusion.

Although survey completion rate was relatively high, a proportion of service users were not contactable by either phone or e-mail. It must be considered that those who did not respond may differ in digital access to survey responders and future studies should provide additional ways of responding (e.g. by post) over longer timeframes. In addition, due to the sample size, groups were compared based on whether they were considered to be from an ethnic minority background, or not, using guidance from the UK classification of ethnicity (Office for National Statistics, Citationn.d.). A larger sample size would allow for the comparison of smaller subsets of ethnic groups.

Conclusions

The majority of participants accepted the offer of remote therapy and had adequate access to digital technology. However, a significant minority of service users declined remote therapy and a significant number remain digitally excluded. Older age remains a key demographic factor influencing uptake of remote therapy, with those declining being older than those who accepted. Lower uptake in older people is potentially related to material provision of digital devices, which was also lower in older individuals. In addition, many people do not have access to large screen devices, which can be considered optimal for remote therapy. Improving confidence in use of technology is perhaps the most tractable method of reducing the digital divide and should be freely available. Equitably supporting people with psychosis via remote therapy will require creative and flexible responses at a local level, and targeted efforts to not leave behind those who may become increasingly less visible as more providers deliver their work via the internet.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ennis, L., Rose, D., Denis, M., Pandit, N., & Wykes, T. (2012). Can't surf, won't surf: The digital divide in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 21(4), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.689437

- Firth, J., Cotter, J., Torous, J., Bucci, S., Firth, J. A., & Yung, A. R. (2016). Mobile phone ownership and endorsement of "mHealth” among people with psychosis: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(2), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv132

- Gay, K., Torous, J., Joseph, A., Pandya, A., & Duckworth, K. (2016). Digital technology use among individuals with schizophrenia: Results of an online survey. JMIR Mental Health, 3(2), e15. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5379

- Greer, B., Robotham, D., Simblett, S., Curtis, H., Griffiths, H., & Wykes, T. (2019). Digital exclusion among mental health service users: Qualitative investigation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(1), e11696. https://doi.org/10.2196/11696

- Hilty, D. M., Chan, S., Torous, J., Luo, J., & Boland, R. J. (2019). A telehealth framework for mobile health, smartphones, and apps: Competencies, training, and faculty development. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 4(2), 106–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-019-00091-0

- Liberati, E., Richards, N., Parker, J., Willars, J., Scott, D., Boydell, N., Pinfold, V., Martin, G., Dixon-Woods, M., & Jones, P. B. (2021). Remote care for mental health: Qualitative study with service users, carers and staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedRxiv, 2021.01.18.21250032. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.18.21250032

- Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Crow, S., Lancaster, K., Simonich, H., Swan-Kremeier, L., Lysne, C., & Myers, T. C. (2008). A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa delivered via telemedicine versus face-to-face. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(5), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.004

- NHS England. (2014). Five year forward view. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

- NHS. (2019). The NHS long term plan. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

- Ofcom. (2020). Online nation – 2020 report (p. 176). Ofcom.

- Office for National Statistics. (2019a). Internet Access – households and individuals, Great Britain: 2019. Retrieved from 2019a

- Office for National Statistics. (2019b). Exploring the UK's digital divide. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/articles/exploringtheuksdigitaldivide/2019-03-04#how-does-digital-exclusion-vary-with-age

- Office for National Statistics. (n.d.). Ethnic Group. London. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160106185816/ http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guidemethod/measuring-equality/equality/ethnic-nat-identity-religion/ethnic-group/index.html

- Olphert, W., & Damodaran, L. (2013). Older people and digital disengagement: A fourth digital divide? Gerontology, 59(6), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353630

- Peters, E., Crombie, T., Agbedjro, D., Johns, L. C., Stahl, D., Greenwood, K., Keen, N., Onwumere, J., Hunter, E., Smith, L., & Kuipers, E. (2015). The long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis within a routine psychological therapies service. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 1658. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01658

- Robotham, D., Satkunanathan, S., Doughty, L., & Wykes, T. (2016). Do we still have a digital divide in mental health? A five-year survey follow-up. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(11), e309. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6511

- Shore, J. H., Schneck, C. D., & Mishkind, M. C. (2020). Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic-current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(12), 1211–1212. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643

- Thomas, N., McDonald, C., de Boer, K., Brand, R. M., Nedeljkovic, M., & Seabrook, L. (2021). Review of the current empirical literature on using videoconferencing to deliver individual psychotherapies to adults with mental health problems. Psychology and Psychotherapy:Theory, Research and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12332

- Tobitt, S., & Percival, R. (2019). Switched on or switched off? A survey of mobile, computer and Internet use in a community mental health rehabilitation sample. Journal of Mental Health, 28(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1340623

- Vaportzis, E., Giatsi Clausen, M., & Gow, A. J. (2017). Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: A focus group study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01687

- Wagner, B., Horn, A. B., & Maercker, A. (2014). Internet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152–154, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.032

- Wykes, T., & Brown, M. (2016). Over promised, over-sold and underperforming? - e-health in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 25(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124406

- Zhai, Y. (2021). A call for addressing barriers to telemedicine: Health disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(1), 64–66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509000

- Zhou, X., Snoswell, C. L., Harding, L. E., Bambling, M., Edirippulige, S., Bai, X., & Smith, A. C. (2020). The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 26(4), 377–379. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0068