Abstract

Background

The value of establishing roles for people with lived experience of mental distress within mental health services is increasingly being recognised. However, there is limited information to guide the introduction of these roles into mental health services.

Aims

This study details the development and evaluation of a new mental health peer worker role, the Lived Experience Practitioner (LXP), within an NHS Trust.

Methods

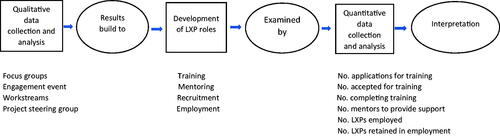

A three-phase exploratory mixed-methods approach was used. Qualitative data were collected and analysed in the first phase. The qualitative findings were then translated into the formal procedures for introducing LXPs into the Trust, with the approach examined quantitatively in the third phase.

Results

The qualitative analysis identified five themes; role design, training, piloting, career pathways and communication. These formed the basis for working groups (workstreams) which developed policies and procedures for introducing the LXP role into the Trust. Twenty-eight applicants commenced a training programme with 10 successful completions. Seven LXPs were employed by the Trust and were still in their posts after 2 years.

Conclusion

In this study, three areas were viewed as important when introducing LXP roles into mental health services; organisational support, the training programme and employment procedures.

Introduction

This study examines the development and introduction of a new mental health peer support worker role, the Lived Experience Practitioner (LXP), in a UK National Health Service (NHS) Trust. The term Lived Experience Practitioner (LXP) was selected by service users who wanted to differentiate their job title from the more traditional designation of peer support worker with the title formally adopted by the Trust. Service users viewed LXP as appropriate for the role as it explicitly recognised their lived experience as a major element in how they offered support and care for people with mental health problems. In the paper, the term Lived Experience Practitioner is used to describe the functions and activities related to the Trust role while the term peer support worker is used when detailed by other authors.

Peer support work

Formalised PSW roles are becoming more familiar with 862 recorded as working within NHS mental health services during September 2019 (HEE, Citation2020). In the United Kingdom, clinical guidelines encourage the employment of peer workers who have recovered or remain stable (NICE, Citation2014) with Gillard et al. (Citation2017) noting the majority of NHS Mental Health Trusts employ peer workers in some capacity across a range of services. Peer Support Workers (PSWs) use their own lived experience of mental distress and social recovery to offer hope and provide support to those in crisis or at an earlier stage in their recovery (Bradstreet & Pratt, Citation2010; Gillard et al., Citation2013; Repper & Carter, Citation2011). They also help service users and staff gain insight into each other’s perspectives (McLean et al., Citation2009).

To help successfully introduce PSW roles, Gillard et al. (Citation2017) suggest collaborative working allows service developments to be informed by service users who are best placed to know what works with regular meetings between clinical teams and PSWs viewed as helpful (Repper & Carter, Citation2011). Ensuring role clarity is also seen as important (Gillard et al., Citation2013; MacLellan et al., Citation2015; Watson, Citation2012) while the use of reasonable adjustments helps retain PSWs (Byrne et al., Citation2018). Ibrahim et al. (Citation2020) note a potential barrier to introducing PSW roles is organisational culture as services often adopt a risk-averse approach. The importance of preparatory role-specific training and support when introducing new PSW roles is encouraged (Rebeiro Gruhl et al., Citation2016) to acknowledge the credibility of PSW roles (Gillard et al., Citation2014; Gillard & Holley, Citation2014), develop clear role expectations (Simpson et al., Citation2018) and support acceptance of roles amongst non-peer colleagues (Collins et al., Citation2016). Despite this guidance, there appears to be limited information describing the introduction of a PSW role into a Trust setting and evaluations of this introduction. This study sought to detail the procedures used to develop the LXP role in one NHS Trust and examine outcomes following its introduction.

Aims

The aim was to examine the introduction of LXPs into the adult mental health workforce of an NHS Trust. The objectives were to:

identify the important factors required for the implementation of LXPs into the Trust

record the procedures used to support the introduction of LXPs into the Trust

examine the number of the LXP’s employed by the Trust and the retention rates.

Method

A three-phased exploratory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2018) was used (). Qualitative data was collected and analysed in the first phase. The second, development, phase was where the qualitative findings were translated into an approach to introduce LXPs into the Trust, with the approach examined quantitatively in the third phase.

Figure 1. Exploratory sequential design of introduction of LXP roles (after Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2018).

An LXP project management group was established which included service users, managers, clinicians and project lead (the first author). The implementation followed the four sequential stages for establishing peer worker initiatives recommended by Repper (Citation2013); preparation, recruitment, employment and ongoing development.

Phase 1: qualitative data collection and analysis

Qualitative data was collected to identify the important factors for inclusion in developing LXP roles through two activities: (i) three focus groups and (ii) round table discussions.

All participants provided informed consent before the focus groups. A purposive sampling approach was used (Clarke & Braun, Citation2013) with individuals involved in existing peer support initiatives (i.e. user engagement activities, volunteering and service-user researcher projects) contacted by the research team via email and invited to participate. The process of conducting focus groups was guided by the practical approach detailed by Krueger and Casey (Citation2014). The key questions asked were:

What are the key elements of peer support?

What tasks would be appropriate for peer support workers to undertake?

What should be included to develop peer support?

The groups were audio-recorded and transcribed.

A Trust-wide engagement event was also held for staff and volunteers engaged in service-user involvement or informal peer support activities. The event showcased the LXP project and other Trust social inclusion initiatives with presentations sharing clinicians' and service users’ experiences of co-production and informal peer support. The event was attended by Trust service users, clinicians and managers. Information about the study was shared with all attendees, upon registration, with everyone invited to participate in guided round table discussions groups. Fifty-five participants volunteered and were involved in six round table discussions with each table containing service users, clinical staff and managers. Written consent was obtained from all participants before the start of the discussion. Participants were asked one central question; “What factors are considered important when introducing new peer support roles into the Trust?” The facilitator aided the discussion through prompts, such as what do you think should be included in an LXP training programme and which Trust sites would be best to use for the initial introduction of LXPs. Each table had between 8 and 12 participants plus a facilitator and scribe who were members of the project team. The scribes noted down specific comments that were considered important.

The focus group and round-table discussion data were combined before being coded and organised into themes using Clarke and Braun’s (Citation2013) thematic analysis process. This has six phases:

Familiarisation with the data: Reading the data, noting down initial ideas.

Generating initial codes: Coding features of the data across the data set.

Searching for themes: Collating codes into potential themes.

Reviewing themes: Checking the themes in relation to the coded extracts and the entire data set.

Defining and naming themes: Refining the specifics of each theme.

Producing the report: Selection of extract examples.

The lead author undertook the thematic analysis. The codes/themes were shared with members of the project team and revisions were made before agreeing with the final themes.

Phase 2: the introduction of LXPs into practice settings

To support the developments and introduction of LXPs into the service, several working groups (called workstreams) were established based on the themes identified in phase 1 of the study. The workstreams were composed of clinicians, Trust management, support staff (from human resources, occupational health and finance) and service users. Attendees at the engagement event were invited to register their interest in being part of a workstream based on their experience and interests. Once the areas of focus for the workstreams had been agreed upon, those who had registered an interest were contacted and invited to join one of the workstreams. The workstream’s developed policies and practices to support the introduction of the LXPs into the Trust. The groups met monthly and reported to the project management group who incorporated these recommended policies and procedures into an overall set of practices.

Phase 3: quantitative data collection and findings

Phase 3 of the study recorded quantitative information obtained from Trust records concerning the number of applications for training, the mentors supporting the training programme and the numbers employed by the Trust following successful completion of the training.

Ethical approval

Health Research Authority approval was obtained through the Research and Development department at Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust. Approval was also given by the Research Ethics Panel at Canterbury Christ Church University (Ref: 17/FHW/17-007).

Results

Phase 1: qualitative findings

Three focus groups were conducted. The first group comprised of service users (n = 5), the second of clinical staff (n = 4) and the final group of Trust organisational leaders (n = 4). Each was facilitated by the first author and another member of the project team and lasted 45–90 min.

Five key themes were identified and detailed in ; role design, training, pilot, career pathway and communications.

Table 1. Qualitative analysis.

Theme 1: role design

This highlighted the importance of clearly defining LXP roles and ensuring their relevance for the services where they would work.

“It’s a support role…They could support, for example, a group co-facilitator with the therapist.” (Organisational leader focus group)

“Roles can be specifically created for peer support workers where they are giving kind of practical, hands-on guidance about, “this is what I went through and this is what you do.” Because a professional will not be able to tell you that because they haven’t been through that…So, using the kind of practical experience that they have.” (Organisational leader focus group)

“Roles should be an appropriate fit to the services they are working within” (Round table)

Theme 2: training

It was important that any training programme used both taught sessions and practical experience to prepare for LXP roles with training also needed for clinical staff.

“Trainees need practical experience…in addition to taught input.” (Round table)

“Need to learn about the equality and diversity of situations. It’s all part of understanding the person that you’re with so that you don’t offend.” (Clinical staff focus group)

“Key part of the training is that we are talking about peer support workers working with other staff and that there’s training for the other staff so that they know what they can ask or expect from a peer support worker.” (Service user focus group)

Theme 3: piloting

It was important to pilot procedures for introducing LXP roles into the Trust, such as identifying suitable locations for piloting LXP roles.

“You can definitely see a role, say, on each ward (where) there is (existing) peer support workers attached.” (Organisational leader focus group)

Theme 4: career pathways

Career progression was important including the possibility of assuming management roles.

“A peer worker would be very high up in manager roles. It’s good because they’ve (staff) got their professional background and people (users) have their life experience of mental health problems which would just help them to understand.” (User focus group)

“I think it’s also about how they are supported so that if, in an ideal situation, peer support workers are feeling supported enough that their personal development is at the heart of it all.” (Organisational leader focus group)

Theme 5: communication

There was a need for a clear communication strategy to widely disseminate information about the project.

“(The) project needs to be communicated throughout the Trust.” (Round Table discussion).

“Recovery leaflets are always pretty current, aren’t they? We’re not involved with communications but maybe we should be?” (Service user focus group)

Phase 2: introduction of LXPs

The themes identified in phase 1 were used as the basis for establishing five workstreams (). The workstreams developed policies and practices informing the introduction of LXPs into the Trust, detailed below.

Pre-appointment training

A 12-week pre-appointment training programme was developed. The programme was primarily developed by the training workstream and further informed by examining external peer support worker training programmes (Repper & Watson, Citation2012). The training covered: work readiness skills, recovery, self-management, personal development, social inclusion, focus on self, peer-to-peer working and working in systems. Sessions were delivered by a Trust facilitator, service users and health care professionals.

The trainees kept a written portfolio using reflective writing to demonstrate their understanding of the LXP work role. The course facilitator had an experience of teaching healthcare in adult education settings and was encouraged to submit draft written work for comment with individual tutorials also supporting the reflective writing process. The assessment criteria for portfolios was adapted from an accredited work-based learning programme (Griggs et al., Citation2015). Training portfolios were assessed by the course facilitator and the Trust lead for social inclusion and evaluated as either a pass or referral. Trainees were eligible to apply for paid LXP roles once passing the training. The initial training programmes were offered to existing Trust volunteers and promoted via emails, flyers and face-to-face meetings.

Mentoring programme

This programme was predominantly informed by work undertaken in the training and role design workstreams. Individual trainees were assigned a mentor from either a clinical, management or support background to provide insight into Trust processes and build relationships with non-LXP colleagues. Support for mentors was offered via a preparatory training session and support meeting during training. Preparatory training for mentors included detailed information about the LXP role, how to reflect on LXP’s strengths and weaknesses and techniques to support LXPs to develop and apply their skills. The training was informed by best practices from the Trust’s existing Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) mentoring programme. A mentoring guide was developed detailing the advice and support offered. Each mentor and trainee met a minimum of three times during the twelve-week training programme with the mentor also providing shadowing opportunities for the trainee.

Recruitment

The recruitment strategy was guided by the role design, piloting and communication workstreams. Following successful completion of the training programme, individuals were eligible to apply for LXP roles advertised via the UK NHS jobs website. This included a Trust-wide strategic Lead LXP post which also entailed supporting the other LXPs. All applicants were encouraged to disclose disabilities when initially contacting the Trust to enable access to reasonable adjustments including hard copy versions of application packs and later interview start times.

All shortlisted applicants were invited to a central recruitment day. On arrival, applicants were given information about the structure of the day, the interview process and clinical areas recruiting LXPs. Interviews were held with representatives from service recruiting to LXP posts. This ensured services were familiar with successful candidates before LXPs joining teams. Applicants were notified of the outcome of their interview by phone call and formal letter.

Employment

Roles were established in a range of community and ward-based services with the employment process guided by the role design, piloting and career progression workstreams. LXP posts were converted from vacant Health Care Assistant (HCA) posts and graded at a similar level apart from the Lead LXP grade which was comparable to a newly qualified nurse or occupational therapist. Ongoing supervision for LXPs was provided by mentors. LXPs also had access to a Continuing Development Programme led by the Lead LXP.

Phase 3: quantitative findings

During the period of the study, two cohorts of service users undertook the training programme ().

Table 2. Training programme.

Recruitment to pre-appointment training

The first two training programmes received 38 applications (18 for cohort 1 and 20 for cohort 2) with 28 attending the training programme (12 for cohort 1 and 16 for cohort 2). The reasons for being unsuccessful included, not yet able to complete a training programme and being perceived as needing to gain greater experience of volunteering work. Two applicants not offered a place in the first cohort joined the second training cohort after gaining further experience of volunteering.

Pre-appointment training

Six trainees successfully completed the training in cohort 1 and four in cohort 2. The main reasons for non-completion were; incomplete or non-submission of the portfolio (n = 10) and leaving the programme (n = 8) (i.e. paid employment elsewhere, further study other volunteering opportunities, health issues and personal factors).

Twelve mentors were recruited in both cohorts to support the trainees. Mentors came from a variety of clinical, management and support staff backgrounds. In cohort 2, some mentors supported more than one LXP trainee.

Employment and retention of LXP roles

Specific job descriptions were developed that detailed the “lived experience” role the appointees were being asked to perform. Across the two cohorts, ten individuals were eligible to apply for paid LXP roles with seven employed. The details are noted in . One Lead LXP and six LXP HCAs were appointed to different services in the Trust. The majority were employed in a part-time capacity. All seven LXPs remained in post-two years after appointment.

Table 3. Employment and retention.

Discussion

To introduce LXPs into the adult mental health workforce of an NHS Trust, a three-stage process was adhered to identifying important areas to be incorporated into the development of LXP roles, incorporating these factors into an implementation process and recording the impact of these interventions in relation to training and employment. Throughout this process, all policies and procedures were developed collaboratively with staff and user involvement in all decision-making. The preparation stage of the LXP project identified five areas that guided the focus of the workstreams in developing coordinated policies and procedures to support the introduction of LXPs into the Trust. This resulted in 28 applicants recruited to a training programme with 10 successfully completing the programme and seven employed by the Trust in newly created LXP posts in the Trust. When reviewing the process, three areas can be viewed as of crucial importance when introducing LXP roles into this Trust: organisational support, the training programme and employment procedures.

Organisational support

Underpinning the introduction of the LXP role was strong support from the Trust. This created a supportive working environment (McLean et al., Citation2009). Support from the Trust came in a range of ways; actively supporting the strategy through providing resources for training and supervision, creating LXPs posts in the Trust and encouraging all staff (clinical and support) to contribute to the development work. This support was further reinforced by internal and external organisational statements in support of the LXP roles (Repper, Citation2013). The development of LXP roles was part of a more extensive and consistent vision to create sustainable user involvement in the development of services as advocated by Gates and Akabas (Citation2007). This included establishing a user research group, a support group for staff members identifying as having mental health difficulties and using co-production within service re-design. Without the organisational support, it is unclear whether the roles would have been developed or whether Trust staff and users would have become involved in the development and implementation of the LXP role.

Training programme

Applying for an LXP role was dependent on successfully completing a training programme. Therefore, there was a need for access to appropriate training (Bradstreet & Pratt, Citation2010; Gillard et al., Citation2013; Repper & Carter, Citation2011). The training programme prioritised practical and taught input as important components. It included examining when and how to share lived experiences and disclose personal information (Repper, Citation2013). There was also an examination of LXP roles in different settings to give an overview of the different locations they could be employed (Castelein et al., Citation2008; Cook et al., Citation2012; Moll et al., Citation2009). The programme was developed in parallel with the development of employment procedures allowing the programme to focus on the requirements of the LXP role. The training was augmented by LXP trainees being mentored and shadowing current staff. This provided the trainees with insight into Trust working, helped build positive relationships with these experienced staff members and allowed them to consider how LXP roles could be encompassed into existing services (Collins et al., Citation2016; MacLellan et al., Citation2015).

Thirty individuals were enrolled over the period of the study with ten successfully completing the training. In the UK, Simpson et al. (Citation2014) reported 13 out of 18 (72%) successfully completed the peer worker training with similar success rates recorded in two Hong Kong studies (Tse et al., Citation2014; Yam et al., Citation2018). These rates contrast with the figure of 36% in this study with ten of the trainees not completing the training due to incomplete or non-submission of their portfolio. This suggests there were problems with what was being asked of the trainees in developing a portfolio, and the need to revisit the assessment procedures, including whether developing a portfolio is the best approach. There have been suggestions peer support workers need to demonstrate a certain degree of recovery to undergo training for roles (Ley et al., Citation2010, Repper, Citation2013). Health issues and personal factors only accounted for two non-completions suggesting trainees in this study were able to deal with the stressors attached to undertaking a training programme.

Employment procedures

Seven out of ten trainees who completed the training gained an LXP position at the Trust. This is slightly more than the 61% of the successful trainees employed in Simpson et al. (Citation2014) study. This suggests the training programme supported those successful trainees in developing knowledge and skills that met the requirements of services in the Trust. All seven LXPs were still in employment at 24 months post-appointment. Several factors are likely to have contributed to the high retention rate in this study. Gillard and Holley (Citation2014) stated there was evidence a clear job description for peer workers facilitated good team working. The role design and career progression workstreams included clinicians, service users, managers and HR personnel allowing job descriptions to be created that met relevant employment protocols and were clear in terms of determining what responsibilities and functions the LXPs would be tasked to do. The duties and scope of the LXP roles were mirrored by the content of the training programme. Ehrlich et al. (Citation2020) found PSWs were embraced as legitimate team members when they shared the existing beliefs and values of the clinical team. In line with recommendations from Repper and Carter (Citation2011), the LXPs and team managers were able to discuss the nature and fit of the role at the recruitment event. This helped place LXPs in appropriate roles which were not too stressful or isolated (Repper, Citation2013). Gillard and Holley (Citation2014) noted resistance among existing staff could also be encountered when a peer worker role was introduced into a team in place of an existing staff role. The decision to only create LXPs roles in existing vacant HCA positions may have helped reduce resistance amongst current staff. The use of “reasonable adjustments” for LXPs in the workplace as recommended by Repper (Citation2013) resulted in many LXPs choosing to work part-time which allowed them a period of acclimatisation to a new working environment. McLean et al. (Citation2009) also found it was important to ensure services were able to recruit to peer support worker posts once they had been established. Planning for these new posts to be promoted at the same time as the end of the training programmes allowed the LXPs to be recruited to newly-created posts.

Limitations

This study had a small sample size and focused on introducing the LXP role to one NHS Trust. It is not possible to make generalisable statements from an examination of one project.

Conclusion

This study found LXP roles were able to be successfully developed and introduced to an NHS Trust with the voices of service users and staff included in the development. In this study, three areas were considered important for the development and implementation of these roles; organisational support, the training programme and the employment procedures.

Strong formal and informal organisation support encouraged members of staff from several areas in the trust to support the development of LXP roles and encouraged service users to become involved. The training programme contained practical and taught elements focusing on preparing the LXP trainees in developing the skills required to work as an LXP and understanding the roles they would be asked to undertake in the Trust. It appeared to adequately prepare the trainees to work in services in the Trust. However, the assessment procedures to enable successful completion of the programme were problematic and the use of portfolios as the assessment approach would benefit from being reviewed. The employment procedures dovetailed with training programme activities. Training and mentoring were supported by clear job descriptions with the recruitment process aiming to ensure LXPs were employed in roles suited to their individual aspirations and expertise. The finding that all seven initial appointees were still in past after 24 months suggests the employment procedures were successful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bradstreet, S., & Pratt, R. (2010). Developing peer support worker roles: Reflecting on experiences in Scotland. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 14(3), 36–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5042/mhsi.2010.0443

- Byrne, L., Stratford, A., & Davidson, L. (2018). The global need for lived experience leadership. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(1), 76–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000289

- Castelein, S., Bruggeman, R. J., Van Busschbach, J. T., van der Gaag, M., Stant, A. D., Knegtering, H., & Wiersma, D. (2008). The effectiveness of peer support groups in psychosis: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01216.x

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Collins, R., Firth, L., & Shakespeare, T. (2016). Very much evolving: A qualitative study of the views of psychiatrists about peer support workers. Journal of Mental Health, 25(3), 278–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2016.1167858

- Cook, J. A., Copeland, M. E., Jonikas, J. A., Hamilton, M. M., Razzano, L. A., Grey, D. D., Floyd, C. B., Hudson, W. B., Macfarlane, R. T., Carter, T. M., & Boyd, S. (2012). Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using wellness recovery action planning. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4), 881–891. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr012

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Ehrlich, C., Slattery, M., Vilic, G., Chester, P., & Crompton, D. (2020). What happens when peer support workers are introduced as members of community-based clinical mental health service delivery teams: a qualitative study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1612334

- Gates, L. B., & Akabas, S. H. (2007). Developing strategies to integrate peer providers into the staff of mental health agencies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 34(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0109-4

- Gillard, S., Edwards, C., Gibson, S., Holley, J., & Owen, K. (2014). New ways of working in mental health services: A qualitative, comparative case study assessing and informing the emergence of new peer worker roles in mental health services in England. Health Services and Delivery Research, 2(19), 1–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02190

- Gillard, S., Edwards, C., Gibson, S., Owen, K., & Wright, C. (2013). Introducing peer support worker roles into UK mental health service teams: A qualitative analysis of the organisational benefits and challenges. BMC Health Services Research, 13(188), 188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-188

- Gillard, S., Foster, R., Gibson, S., Goldsmith, L., Marks, J., & White, S. (2017). Describing a principles-based approach to developing and evaluating peer worker roles as peer support moved into mainstream mental health services. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(3), 133–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-03-2017-0016

- Gillard, S., & Holley, J. (2014). Peer workers in mental health services: Literature overview. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20(4), 286–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.113.011940

- Griggs, C., Hunt, L., & Reeman, S. (2015). Education and progression for support workers in mental health. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 10(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-10-2014-0031

- HEE (2020). National Workforce Stocktake of Mental Health Peer Support Workers in NHS Trusts Report V1.2. Retrieved February 15, 2021, from https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/NHS%20Peer%20Support%20Worker%20Benchmarking%20report.pdf

- Ibrahim, N., Thompson, D., Nixdorf, R., Kalha, J., Mpango, R., Moran, G., Mueller-Stierlin, A., Ryan, G., Mahlke, C., Shamba, D., Puschner, B., Repper, J., & Slade, M. (2020). A systematic review of influences on implementation of peer support work for adults with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01739-1

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5nd ed.). Sage.

- Ley, A., Roberts, G., & Willis, D. (2010). How to support peer support: evaluating the first steps in a healthcare community. Journal of Public Mental Health, 9(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5042/jpmh.2010.0160

- MacLellan, J., Surey, J., Abubakar, I., & Stagg, H. R. (2015). Peer support workers in health: A qualitative metasynthesis of their experiences. PLOS One, 10(10), e0141122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141122

- McLean, J., Biggs, H., Whitehead, I., Pratt, R., & Maxwell, M. (2009). Evaluation of the delivering for mental health peer support worker pilot scheme. Scottish Government.

- Moll, S., Holmes, S., Geronimo, J., & Sherman, D. (2009). Work transitions for peer support providers in traditional mental health programs: Unique challenges and opportunities. Work, 33(4), 449–458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0893

- NICE (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178

- Rebeiro Gruhl, K., LaCarte, S., & Calixte, S. (2016). Authentic peer support work: Challenges and opportunities for an evolving occupation. Journal of Mental Health, 25 (1), 78–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1057322

- Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947

- Repper, J., & Watson, E. (2012). A year of peer support in Nottingham: Lessons learned. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 7(2), 70–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17556221211236466

- Repper, J. (2013). ImROC briefing paper 5. Peer support workers: Theory and practice. ImROC. https://imroc.org/resources/5-peer-support-workers-theory-practice/

- Simpson, A., Oster, C., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2018). Liminality in the occupational identity of mental health peer support workers: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 662–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12351 28548455

- Simpson, A., Quigley, J., Henry, S., & Hall, C. (2014). Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20131126-03

- Tse, S., Tsoi, E. W. S., Wong, S., Kan, A., & Kwok, C. F.-Y. (2014). Training of mental health peer support workers in a non-western high-income city: Preliminary evaluation and experience. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013481427

- Watson, E. (2012). One year in peer support – personal reflections. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 7(2), 85–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17556221211236484

- Yam, K., Lo, W., Chiu, R., Lau, B., Lau, C., Wu, J., & Wan, S. M. (2018). A pilot training program for people in recovery of mental illness as vocational peer support workers in Hong Kong – Job Buddies Training Program (JBTP): A preliminary finding. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 132–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.002