Abstract

Background

Previous research has observed positive associations between perceived quality of social support and mental well-being. Having access to functional social support that provides sources of care, compassion and helpful information have shown to be beneficial for mental health. However, there is a need to identify the psychological processes through which functional social support can elicit therapeutic outcomes on mental well-being.

Aims

The present cross-sectional study aimed to examine the extent to which self-efficacy and self-esteem mediated the association between functional social support and mental well-being.

Method

Seventy-three people with a mental health diagnosis, who attended group-based activities as facilitated by a third sector community mental health organisation, took part in the present study. Participants were required to complete measures that assessed perceived quality of functional social support, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and subjective mental well-being.

Results

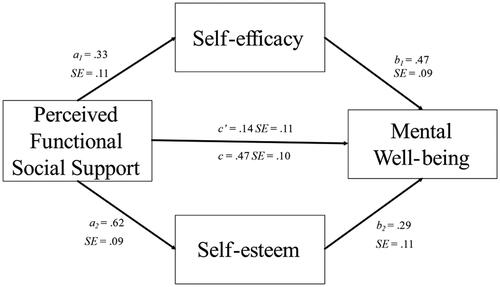

A multiple mediation analysis revealed that self-efficacy and self-esteem fully mediated the positive association between perceived functional social support and mental well-being.

Conclusions

The implications of these results are that social interventions, which aim to facilitate the delivery of functional social support, could enhance mental well-being via their positive effects on self-efficacy and self-esteem.

Introduction

Globally, it has been estimated that over 1 billion people experience a mental health disorder at some point during the lifespan (Rehm & Shield, Citation2019). It has been posited that social factors, such as loneliness and lack of access to social support, can contribute to the onset and perpetuation of mental health difficulties (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2014). Lacking social support or being socially disconnected from others for prolonged periods of time has been associated with depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation (Leigh-Hunt et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, lower levels of perceived social support have been associated with greater symptom severity in mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder (Wang et al., Citation2018). Receiving social support that provide sources of care, attention and a sense of being valued by others can serve as an effective buffer to challenging life events and also enhance mental well-being (Cobb, Citation1976). Therefore, having access to social support could serve as a protective factor and help ameliorate symptoms in people with mental health difficulties.

There are two distinct types of social support, which are 1) structural support and 2) functional support (Wang et al., Citation2017). Structural social support refers to the size and extent to which people access their social networks. Functional social support has been defined as the perceived quality of interactions with people who provide sources of care, compassion and solutions to overcome challenging life events (Lakey & Cohen, Citation2000). There is also literature to suggest that there are other types of social support, including 1) emotional, 2) informational and 3) concrete/financial support (Tracy & Abell, Citation1994). Perceived social support has been identified as a potential protective factor that can reduce symptoms within clinical populations of people who have a mental health diagnosis. For example, higher levels of perceived social support has been associated with lower symptoms of depression in people during their treatment in inpatient mental healthcare services (McDougall et al., Citation2016). Social support has also been observed to be a protective factor against attempted suicide in people with mental health diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kleiman & Liu, Citation2013). This would suggest that interventions that modify perceived functional social support could lead to better therapeutic outcomes on psychological well-being in people who have a mental health diagnosis.

However, although positive associations have been observed between functional social support and well-being, it is of interest to identify the psychological processes through which social support can elicit therapeutic outcomes on psychological well-being (Thoits, Citation2011). Identification of mediators, or mechanisms of change, can be an essential step to the development of interventions that aim to support the recovery of people who experience mental health difficulties (Murphy et al., Citation2009). Mediation analysis can help to establish the underlying processes through which interventions can improve therapeutic outcomes (Windgassen et al., Citation2016). For example, Birtel et al. (Citation2017) used mediation analysis to identify potential mediators through which perceived social support could enhance sleep quality in people who have a substance abuse disorder. It was observed that self-stigma significantly mediated associations between perceived social support and sleep quality. This would indicate that perceived social support that is conducive to reducing self-stigma could lead to therapeutic outcomes through improving sleep quality in people who have a substance misuse disorder. Thus, identification of potential mediators, could help to ascertain the psychological processes that social interventions could target as a means to facilitate therapeutic outcomes on mental well-being.

Self-efficacy is one psychological process that could help explain the previously observed associations between functional social support and mental well-being. Self-efficacy has been defined as the way in which people appraise their own ability to successfully implement strategies in order to achieve particular goals (Bandura, Citation1977). Low levels of self-efficacy can have detrimental consequences on mental well-being and has been associated with greater levels of anxiety (Iancu et al., Citation2015) and symptoms of depression (Liu et al., Citation2019). In contrast, higher levels of self-efficacy have been associated with greater overall satisfaction with life (Azizli et al., Citation2015), higher ratings of subjective health (Jeong et al., Citation2019) and well-being (Soysa & Wilcomb, Citation2015). Research has shown that accessing social support that enhances notions of self-efficacy can serve to facilitate adaptive coping strategies and lead to beneficial outcomes on overall well-being (Saltzman & Holahan, Citation2002). This would suggest that social interventions that bolster self-efficacy could be effective in facilitating therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, self-efficacy has also shown to mediate a negative correlation between perceived levels of social support and postpartum depression in new mothers with no history of a mental health diagnosis (Zhang & Jin, Citation2016). Thus, self-efficacy could serve as a potential mediator between perceived quality of functional social support and psychological well-being in people with a mental health diagnosis.

Self-esteem is another possible mediator through which functional social support may enhance mental well-being. Self-esteem refers to how people evaluate their own self-worth and value (Trzesniewski et al., Citation2013). Higher levels of perceived social support have been associated with higher levels of self-esteem in school aged children (Tian et al., Citation2013), nurses (Feng et al., Citation2018) and autistic adults (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). It has also been argued that interventions that improve self-esteem could be effective in negating or reducing symptoms of depression and enhancing overall mental well-being (Sowislo & Orth, Citation2013). For example, mindfulness-based interventions that are effective in improving self-esteem have shown to lead to therapeutic outcomes on mental well-being (Bajaj et al., Citation2016). Self-esteem has also shown to mediate a positive association between social support and subjective well-being within people who have physical disabilities (Ji et al., Citation2019). Thus, it is of interest to ascertain if self-esteem, along with self-efficacy, is a potential mechanism of change through which functional social support can influence levels of mental well-being. There is some evidence to suggest that both self-esteem and self-efficacy could be improved by attending community mental health services that are delivered in group settings. For example, community based programmes that provide opportunities to engage in group based exercise and nutritional advice have shown to improve self-esteem in people with severe mental illness (Gallagher et al., Citation2021). Similarly, engaging in group-based activities in healthcare settings, such as exercise classes, provides opportunities to develop social relationships and learn new skills from others, which can also enhance self-efficacy (Olsen et al., Citation2015). It is therefore of interest to investigate the extent to which self-esteem and self-efficacy mediates an association between functional social support and mental well-being in people who access group-based community mental health services.

People who experience mental health difficulties are less likely to have access to social support in community settings than individuals who have no history of accessing psychiatric services (Palumbo et al., Citation2015). People who access mental health services can potentially be vulnerable to experiencing social isolation in community settings, which can trigger or perpetuate mental health difficulties (Nolan et al., Citation2011). Research has shown that community mental healthcare services could be well placed to facilitate the delivery of social interventions that provide opportunities to engage in meaningful activities and harness a sense of being socially supported by others (Tew et al., Citation2012). For example, participation in group-based arts activities in community settings, such as singing and creative writing, has shown to be beneficial in improving the psychological well-being of adults with chronic mental health difficulties (Williams et al., Citation2019). Group-based activities that incorporate physical exercise have also shown to bolster self-esteem in people with a mental health diagnosis (Barton et al., Citation2012). It has also been recognised that engaging in group-based programmes that provides opportunities to access social support from peers and healthcare professionals can enhance health related self-efficacy (Mladenovic et al., Citation2014). This would suggest that accessing group-based activities could enhance self-esteem and self-efficacy. Furthermore, social interventions that facilitate group-based activities in community settings may provide people with mental health difficulties opportunities to access functional social support from healthcare professionals and their peers (Newman et al., Citation2015). It has been argued that self-efficacy and self-esteem are two distinct constructs in which self-efficacy relates to a person’s judgement of their capability to complete particular tasks and is linked to intrinsic motivation, whereas self-esteem refers to how people evaluate their own self-value which can impact affective states (Chen et al., Citation2004). Therefore, it is of interest to ascertain if self-efficacy and self-esteem are two psychological processes through which perceived functional social support could influence the psychological well-being of people with a mental health diagnosis who engage in group-based activities in community settings.

The present study examined a mediation model to ascertain if any associations between perceived functional social support and psychological well-being are mediated via self-efficacy and self-esteem. This mediation model was assessed in the context of people who have a mental health diagnosis and attended group-based activities within a community mental healthcare organisation.

Method

Design

The current study examined a cross-sectional mediation model to assess if perceived functional social support had an indirect effect on mental well-being via the psychological constructs of self-esteem and self-efficacy.

Participants

73 participants who attended a third sector community mental healthcare organisation in the North-East of England were recruited to take part in the study, of which 25 identified as being female (Mean age = 45.88, SD = 17.21) and 48 identified as being male (Mean age = 43.10, SD = 11.96). A post-hoc power analysis, based on the Sobel Test via the WebPower package in R (Zhang & Yuan, Citation2018) indicated 84% power in the statistical analysis used in the present study and was deemed acceptable as it surpassed the .80 level (Cohen, Citation2013). The 73 participants had been referred to the organisation in order to engage with group-based activities that took place on a weekly basis. The group activities facilitated participants’ involvement in arts and also exercise based programmes under the guided supervision of qualified support staff. Further anonymised details regarding the type of group-based activities that the participants were engaged in a the time of data collection can be found at the following Open Science Framework link: https://osf.io/324wp/?view_only=5c26b2b8df2f40d1aa329eb04a791157

All participants had a mental health diagnosis at the time of data collection, details of which can be found in . For recruitment purposes, authors S.W and A.L advertised details of the study within a charitable community mental healthcare organisation to recruit participants. Appointments were arranged between potential participants who expressed an interest in taking part in the study, a designated support worker and the second author. These appointments took place within a private room on the site of the organisation that was hosting the study. The purpose of these appointments was to clearly articulate the aims of the study to participants and outline what participation in the study would comprise of. Potential participants were also notified that participation was optional and that declining to take part would have no impact on their accessing the services of the organisation that hosted this study. Participants who agreed to take part in the study were required to sign an informed consent sheet prior to their participation.

Table 1. Details of the mental health diagnoses of consenting participants.

Psychological measures

Functional social support

The 8-item version of the Social Provisions Scale (Cutrona & Russell, Citation1987) as modified by Steigen and Bergh (Citation2019) was used as a self-report measure for perceived functional social support. The utility of the 8-item version of the Social Provision Scale has been recommended when assessing perceived functional social support in people who have a mental health diagnosis (Steigen & Bergh, Citation2019). Functional social support refers to the perceived availability of emotional, companionship and informational support from a given social network. This measure requires participants to respond on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree − 4 = strongly agree), with higher scores, ranging from 8 − 32, indicating greater levels of perceived functional social support. Participants are required to respond on this 4-point Likert scale to items such as ‘I have relationships where my competence and skills are recognised’ and ‘I have close relationships that provide me with a sense of emotional security and well-being’. In the current study the internal consistency of measuring perceived functional social support on this measure was observed to be high (α = .91).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured using the New General Self-efficacy Scale (Chen et al., Citation2001) that comprises of 8 items using 5-point Likert scales (strongly disagree = 1 – strongly agree = 5). Participants are required to respond on this 5-point Likert scale to items such as ‘I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I have set for myself’ and ‘When facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them’. Scores can range from 8 − 40, with higher scores indicating greater levels of perceived self-efficacy. The New General Self-efficacy Scale has previously been used to assess levels of perceived self-efficacy in people who have accessed community mental health services and reside in rural areas (Judd et al., Citation2006). The New General Self-efficacy Scale has also been used to assess the effectiveness of Problem-Solving Therapy in improving self-efficacy in females accessing residential treatment for postpartum depression (Sampson et al., Citation2021). The present study observed a high internal consistency for this measure (α =.84).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg (Citation1965) Self-esteem Scale, which comprises of 10 items requiring participants to respond on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree − 4 strongly disagree). Participants are required to respond on the 4-point Likert scale to items such as ‘On the whole, I am satisfied with myself’ and ‘At times I think I am no good at all’. The scores range from 10 − 40, with higher scores indicating greater levels of perceived self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale has previously been used to assess self-esteem in people who have experienced first episode psychosis (Curtis et al., Citation2016). The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale has also shown to have high internal reliability in measuring global self-esteem in adults with a mental health diagnosis (Torrey et al., Citation2000). The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale is a unidimensional measure of self-esteem, with a good level of internal consistency being observed in the present study (α = .74).

Mental well-being

Mental well-being was quantified using the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009), which consists of 7 items where participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = none of the time − 5 = all of the time). Participants are required to respond on this 5-point Likert scales to items such as ‘I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future’ and ‘I’ve been feeling useful’. Scores on this measure can range from 5 − 35, with higher scores indicating greater mental well-being over the 2 weeks prior to completing the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale. The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale has previously been used to assess mental well-being in people who access community mental healthcare services (Wright et al., Citation2020) The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale is a unidimensional measure of psychological well-being, with a high level of internal consistency being observed in the current study (α = .83).

Procedure

This study was granted ethical approval by the ethics committee at the School of Health and Life Sciences at the University of Northumbria at Newcastle: Reference 17403. For data collection purposes, an online survey platform was built using Qualtrics, to facilitate the collection of basic demographic information and questionnaire data. Data was collected on a face-to-face basis with consenting participants on an individual basis. Participants were also notified that a designated support worker could be present throughout the meeting if required. The survey questions were read out as they were presented on the Qualtrics platform for participants to verbally respond to. The survey questions were read out to participants as requested by service managers of the organisation that hosted the present study. Participants were instructed to provide verbal responses in accordance to the scales attached to the Social Provisions Scale (Steigen & Bergh, Citation2019), General Self-efficacy Scale (Chen, Gully & Eden, Citation2001), Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965) and the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009). Participants’ responses were inputted onto the Qualtrics survey platform accordingly. With this method of data collection, completion of the questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes. Once all questionnaires had been completed, participants were debriefed and thanked for their time.

Analysis

The key analyses were conducted with the R packages, ‘psych’ (Revelle, Citation2017) and ‘party’ (Hothorn et al., Citation2006). The anonymised data, all questionnaires used, and analysis script are available from the Open Science Framework at the following link: https://osf.io/324wp/?view_only=5c26b2b8df2f40d1aa329eb04a791157. This document also contains further analyses and robustness checks.

Results

Correlations between predictor variables and mental well-being

Mental well-being was positively associated with the predictor variables of perceived functional social support (r = .47, p < .001), self-efficacy (r = .59, p < .001) and self- esteem (r = .49, p < .001). provides the correlation coefficients between perceived social support, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and mental well-being.

Table 2. Pearson correlation matrix, means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for all of the measures.

Multiple mediation analysis

illustrates the results of the multiple mediation analysis that examined the association between social support and mental well-being via the constructs of self-esteem and self-efficacy. Greater levels of perceived functional social support was associated with higher self-efficacy t(71) = 2.99, p = .004, and greater self-esteem t(71) = 6.71, p < .001. Greater self-efficacy t(70) = 5.10, p < .001, and higher self-esteem t(70) = 2.59, p = .017 were observed to be associated with greater mental well-being. The indirect effect of social support on mental well-being, via self-efficacy and self-esteem, was calculated using 95% confidence intervals and 10,000 bootstrap iterations. Bootstrap intervals did not contain 0 for both self-efficacy, 95% [0.02, 0.28] and self-esteem, 95% [0.04, 0.34], indicating a significant indirect effect. The direct effect (c’) between perceived social support and mental well-being, was not significant (t(69) = 1.21, p = .232). This suggested that full mediation had occurred via the constructs of self-esteem and self-efficacy.

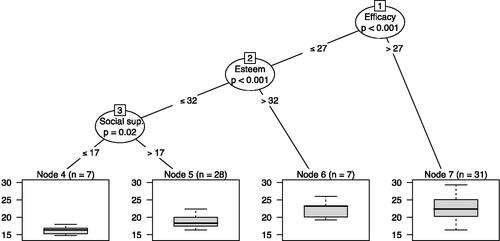

Exploratory decision tree approach

Further to the multiple mediation analysis, we also used a conditional inference tree (Strobl et al., Citation2009) to explore how perceived functional social support, self-efficacy, and self-esteem predict mental well-being in a non-linear way. Simply put, the conditional inference tree approach consists of data being repeatedly divided into subsets via an algorithm, from which we can then examine the decision rules used by the algorithm. Please refer to the following Open Science Framework link to access further details and description of the conditional inference tree analysis used in the present study: https://osf.io/324wp/?view_only=5c26b2b8df2f40d1aa329eb04a791157.

This led to the decision tree in . Those scoring high on self-efficacy (>27) tended to report greater mental well-being. Those low in self-efficacy (< =27) but high in self-esteem (>32), tended to also report greater well-being. However, for those scoring low on self-efficacy (< =27) and self-esteem (< =32), there was a further division based on perceived functional social support. The mental well-being was lowest in the group that reported low perceived functional social support (< =17).

Discussion

The present study examined the role of self-esteem and self-efficacy as mediators between perceived functional support and psychological well-being in people with a mental health diagnosis. The results converge with previous studies (Kleiman & Liu, Citation2013; Lakey & Cohen, Citation2000; McDougall et al., Citation2016), showing a positive association between perceived levels of functional social support and psychological well-being. The present study also indicated that self-esteem and self-efficacy fully mediated the positive association between functional social support and psychological well-being. This would suggest that therapeutic interventions, which aim to facilitate social support for people with mental health difficulties, could focus on enhancing self-esteem and self-efficacy as a means to elicit beneficial outcomes on psychological well-being.

Self-esteem, and the way in which people appraise their own self-worth and value, has previously been identified as an important construct in influencing psychological well-being (Sowislo & Orth, Citation2013). The mediation model in the present study suggests that the perception of receiving functional social support may influence the way people evaluate their own self value, which can then determine psychological well-being. This would suggest that the sense of being valued by others, who provide functional social support, may increase the extent to which people with a mental health diagnosis value themselves and improve self-esteem. Functional social support refers to the process of interacting with people who are seen to provide sources of encouragement, informational support, advice and facilitate a sense of belonging (Lakey & Cohen, Citation2000). It has been posited that group activities facilitated by healthcare professionals, such as dramatherapy, can be beneficial in harnessing social networks between attendees and staff members (Bourne et al., Citation2020). Group-based talking therapies can also be beneficial in reducing symptoms of depression and facilitating recovery through attendees sharing their knowledge, lived experiences and providing guidance to peers (Gillis & Parish, Citation2019). It has been posited that group cohesion, which refers to an individual’s intrinsic desire to be a member of and contribute to a particular group, can be an important facet in ensuring productivity and positive outcomes for people who engage in group-based therapies (Yalom & Rand, Citation1966). For example, longitudinal increases in group cohesion have been associated with improved self-esteem and therapeutic outcomes in people attending group-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy sessions for psychosis (Lecomte et al., Citation2015). Therefore, group-based activities that facilitate cohesion amongst attendees, whilst providing opportunities to receive functional social support from healthcare professionals and peers, may help to ensure self-esteem in people with mental health diagnoses. Thus, social interventions that provide functional social support may improve self-esteem through encouraging positive evaluations of self-worth and value leading to therapeutic outcomes for people with a mental health diagnosis.

Furthermore, the present study also suggests that functional social support indirectly effects psychological well-being via self-efficacy. It has previously been acknowledged that accessing social support that is effective in harnessing higher levels of self-efficacy can serve as a protective factor and ensure mental well-being through challenging or novel life events, such as becoming a parent for the first time (Leahy‐Warren et al., Citation2012). Self-efficacy has been defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to engage with and successfully complete specific tasks (Bandura, Citation1977). It has been argued that self-efficacy can be enhanced through engaging in group activities that have peers who have similar mental health difficulties and are seen to be proactive in their recovery (Bandura, Citation2001). The process of engaging in meaningful activities with peers has shown not only to improve self-efficacy but also enhance psychological well-being in people with mental health diagnoses (Mancini, Citation2007). Furthermore, such activities as group-based exercise can also provide opportunities to engage with staff members and peers who can be viewed as role models and thus facilitate improvements in self-efficacy (Olsen et al., Citation2015). Thus, the process of being connected with people who provide functional social support may help to enhance perceived abilities and increase self-efficacy. This suggests that social interventions that facilitate the delivery of functional social support could aim to focus on enhancing self-esteem and self-efficacy in order to support the recovery of people with a mental health diagnosis in community settings. Social interventions could also measure self-efficacy and self-esteem throughout the delivery of group-based programmes that facilitate the delivery of functional social support as a means to assess therapeutic change in people with a mental health diagnosis.

As an addition to the mediation analysis, an exploratory analysis with a conditional inference tree provided an indication of the cut-off values for the measures used to assess perceived functional support, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. It was notable that participants who reported higher levels of self-efficacy also had greater mental well-being. Thus, from this exploratory analysis, self-efficacy was observed to be the most critical dimension related to mental health well-being, as high levels of self-efficacy were most strongly associated with greater mental health well-being. However, participants who reported lower levels of self-efficacy, but higher levels of self-esteem, also experienced greater levels of mental well-being at the time of data collection. This would suggest that self-esteem could potentially serve as a buffer for people with mental health difficulties during times of experiencing low levels of self-efficacy, as a means to ensure psychological well-being. The conditional inference tree also indicated that participants who reported the lowest levels of perceived functional social support, in combination with low self-efficacy and low self-esteem, reported lower subjective psychological well-being. This has provided an indication of how the psychological constructs of perceived functional social support, self-efficacy, and self-esteem could be influential in determining subjective mental well-being, albeit in a non-linear way. It also provides a further illustration that social interventions could incorporate strategies to ensure that people with mental health difficulties are able to access sources of social support to enhance self-efficacy and self-esteem in order to ensure psychological well-being.

There are some aspects of the method used in the present study that requires consideration when interpreting the results. It must be acknowledged that the present study specifically focussed on and measured the construct of functional social support through administering a brief version of the Social Provision Scale (Steigen & Bergh, Citation2019). It has been acknowledged that the utility of brief measures can be beneficial when conducting social research in healthcare settings where participants may have limited time (Pomare et al., Citation2019). Thus, the brevity of administering the brief version of the Social Provision Scale, to specifically measure functional social support, was beneficial in the present study to ensure that data collection and participation could be conducted within an applied mental healthcare setting in a timely manner. However, a limitation of the present study was that using a brief version of the Social Provisions Scale negated a more holistic assessment of perceived social support. For example, the full version of the Social Provision Scale (Cutrona & Russell, Citation1987) provides a more holistic assessment of perceived social support as it includes subscales such as levels of attachment to others, social integration and opportunities for nurturance. Another limitation in the present study was that participants were required to overtly respond to each item of the measures used in the presence of a member from the research team. It has been posited that overtly responding to questions in the presence of a researcher may elicit socially desirable responses from participants (Tourangeau & Yan, Citation2007). Therefore, subsequent studies may consider utilising self-reported methods of completing measures in this area of research to negate socially desirable responses from participants.

It must also be acknowledged that social support can be provided by various sources, such as family/friends (Thoits, Citation2011), healthcare professionals (Huxley et al., Citation2009) and peers (Mladenovic et al., Citation2014). It is therefore recommended that future studies explicitly assess how these various sources of social support, from significant others, can independently influence the psychological well-being of people with mental health difficulties in community settings. This would help to ascertain if there are particular sources of functional social support in community settings that are more beneficial than others in enhancing the psychological well-being of people with a mental health diagnosis. Subsequent studies may also consider that there are other facets to and methods of assessing the social support of people with mental health difficulties (Gottlieb & Bergen, Citation2010). For example, Social Network Mapping uses interview based methods for data collection and quantitative analysis to illustrate the size and quality of a social network available to people who access mental health services (Beckers et al., Citation2020). Likewise, future studies could explore social integration, which refers to the extent to which people engage in private and public social interactions (Appau et al., Citation2019). The Social Integration Scale has previously been used to assess the social integration of people who have Schizophrenia (Ogundare et al., Citation2021). Mutual social support that includes the process of providing social support to peers has also shown to be beneficial in improving self-esteem and self-efficacy in people with enduring mental health difficulties (Bracke et al., Citation2008). Mutual interactions and having opportunities to provide support to peers can be an important component of social support. For example, perceptions of only receiving support and being a burden to others, such as friends and family, has been associated with symptoms of depression (Bell et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a limitation of the present study was that other facets of social support, such as participants’ social network size, perceived integration and provision of peer support to others, were not measured. Although the present study has provided an illustration of how self-efficacy and self-esteem mediates an association between functional social support and mental well-being, the methodologies of subsequent studies in this area of research could be further improved through measuring other key aspects of social support.

It is also necessary to acknowledge that the participant group in the present study included people who had various mental health diagnoses, as illustrated in . It is therefore important to consider that people who have a particular mental health diagnosis may respond differently to interventions that provide functional social support. It is also necessary to consider that variables, other than self-esteem and self-efficacy, could serve as mechanisms of therapeutic change when implementing therapeutic interventions. For example, people who experience clinical depression, along with low levels of perceived social support, could also be vulnerable to chronic stress (Richardson et al., Citation2012). This would suggest that stress could also be a key mechanism of change when developing or implementing social interventions that aim to elicit therapeutic change in people who have a specific diagnosis of depression. Perceived isolation has also been observed to mediate the association between being socially disconnected and symptoms of anxiety (Santini et al., Citation2020). Perceived isolation has been defined as being deprived of social connections with others and can have deleterious consequences on mood, physical health and cognitive well-being (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2009). Thus, perceived functional social support that is effective in reducing notions of isolation could also elicit therapeutic change in people who have a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder. Furthermore, higher levels of perceived social support have been associated with lower negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Pruessner et al., Citation2011). Therefore, social interventions that aim to reduce negative symptoms associated with psychotic disorders, such as apathy, anhedonia, and social withdrawal, could be therapeutic for people who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Therefore, as the present study comprised of participants who had various different diagnoses, it is important to acknowledge that there may have been underlying mechanisms, other than self-esteem and self-efficacy, which may have contributed to the positive association between perceived social support and mental well-being.

Furthermore, the present study also comprised of a multiple mediation analysis of cross-sectional data. Therefore, the participants’ perceived functional support, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and mental well-being was only assessed at a single point in time. It has been acknowledged that there can be significant barriers to the collection of longitudinal data in clinical populations and that mediation analysis of cross-sectional data in such real-world settings can be necessary and a useful first step in identifying potential mediators of change (Halliday et al., Citation2019; Hayes, Citation2017). Mediation models using cross-sectional data have previously been assessed to identify potential mediators between social support and therapeutic outcomes in clinical populations (Birtel et al., Citation2017). However, perceived quality of social support can potentially fluctuate over periods of time (Cohen et al., Citation2004), while levels self-esteem can also change throughout the lifespan (Robins & Trzesniewski, Citation2005). Self-efficacy can also be acutely determined by levels of state social anxiety (Gaudiano & Herbert, Citation2006). This would suggest that social support, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being can be prone to change over a period of time. Therefore, any changes in perceived functional support, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and subjective psychological well-being cannot be captured in a mediation model that comprises of cross-sectional data. Thus, a mediation analysis of longitudinal data could help to further ascertain if any changes in self-efficacy and self-esteem would cause positive associations between functional social support and psychological well-being over a period of time.

To conclude, the present study aimed to extend the findings of previous research to further examine the psychological processes through which perceived levels of functional social support could influence the psychological well-being of people with a mental health diagnosis who also attended group-based activities in the community. The present study observed a positive association between perceived functional social support and psychological well-being. Furthermore, the positive association between functional social support and psychological well-being was fully mediated by self-esteem and self-efficacy. These findings would suggest that social interventions, which aim to facilitate the delivery of functional social support for people with mental health disorders, could look to focus on enhancing self-esteem and self-efficacy as a means to encourage therapeutic outcomes on psychological well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Appau, S., Churchill, S. A., & Farrell, L. (2019). Social integration and subjective wellbeing. Applied Economics, 51(16), 1748–1761. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1528340

- Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., & Giammarco, E. A. (2015). Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 58–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.006

- Bajaj, B., Gupta, R., & Pande, N. (2016). Self-esteem mediates the relationship between mindfulness and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 96–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.020

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barton, J., Griffin, M., & Pretty, J. (2012). Exercise-, nature-and socially interactive-based initiatives improve mood and self-esteem in the clinical population. Perspectives in Public Health, 132(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913910393862

- Beckers, T., Koekkoek, B., Tiemens, B., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2020). Measuring social support in people with mental illness: A quantitative analysis of the Social Network Map. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(10), 916–924. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1744205

- Bell, C. M., Ridley, J. A., Overholser, J. C., Young, K., Athey, A., Lehmann, J., & Phillips, K. (2018). The role of perceived burden and social support in suicide and depression. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12327

- Birtel, M. D., Wood, L., & Kempa, N. J. (2017). Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Research, 252, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.097

- Bourne, J., Selman, M., & Hackett, S. (2020). Learning from support workers: Can a dramatherapy group offer a community provision to support changes in care for people with learning disabilities and mental health difficulties? British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12312

- Bracke, P., Christiaens, W., & Verhaeghe, M. (2008). Self‐esteem, self‐efficacy, and the balance of peer support among persons with chronic mental health problems. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(2), 436–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00312.x

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2014). Social relationships and health: The toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(2), 58–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12087

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.251

- Cobb, S. (1976). Presidential Address-1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

- Cohen, A. N., Hammen, C., Henry, R. M., & Daley, S. E. (2004). Effects of stress and social support on recurrence in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(1), 143–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.008

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic press.

- Curtis, J., Watkins, A., Rosenbaum, S., Teasdale, S., Kalucy, M., Samaras, K., & Ward, P. B. (2016). Evaluating an individualized lifestyle and life skills intervention to prevent antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12230

- Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1987). The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Advances in Personal Relationships, 1(1), 37–67.

- Feng, D., Su, S., Wang, L., & Liu, F. (2018). The protective role of self-esteem, perceived social support and job satisfaction against psychological distress among Chinese nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(4), 366–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12523

- Gallagher, P., Boland, C., McClenaghan, A., Fanning, F., Lawlor, E., & Clarke, M. (2021). Improved self-esteem and activity levels following a 12-week community activity and healthy lifestyle programme in those with serious mental illness: A feasibility study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 15(2), 367–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12965

- Gaudiano, B. A., & Herbert, J. D. (2006). Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot results. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(3), 415–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007

- Gillis, B. D., & Parish, A. L. (2019). Group-based interventions for postpartum depression: An integrative review and conceptual model. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(3), 290–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.009

- Gottlieb, B. H., & Bergen, A. E. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001

- Halliday, A. J., Kern, M. L., & Turnbull, D. A. (2019). Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 8–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.02.003

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., & Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15(3), 651–674. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1198/106186006X133933

- Huxley, P., Evans, S., Beresford, P., Davidson, B., & King, S. (2009). The principles and provisions of relationships: findings from an evaluation of support, time and recovery workers in mental health services in England. Journal of Social Work, 9(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017308098434

- Iancu, I., Bodner, E., & Ben-Zion, I. Z. (2015). Self esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 165–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.018

- Jeong, I., Yoon, J.-H., Roh, J., Rhie, J., & Won, J.-U. (2019). Association between the return-to-work hierarchy and self-rated health, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 92(5), 709–716. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01406-7

- Ji, Y., Rana, C., Shi, C., & Zhong, Y. (2019). Self-Esteem Mediates the Relationships Between Social Support, Subjective Well-Being, and Perceived Discrimination in Chinese People With Physical Disability. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2230–2230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02230

- Judd, F., Jackson, H., Komiti, A., Murray, G., Fraser, C., Grieve, A., & Gomez, R. (2006). Help-seeking by rural residents for mental health problems: the importance of agrarian values. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(9), 769–776. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01882.x

- Kleiman, E. M., & Liu, R. T. (2013). Social support as a protective factor in suicide: Findings from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 540–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.033

- Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement.

- Leahy‐Warren, P., McCarthy, G., & Corcoran, P. (2012). First‐time mothers: social support, maternal parental self‐efficacy and postnatal depression. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(3-4), 388–397. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03701.x

- Lecomte, T., Leclerc, C., Wykes, T., Nicole, L., & Abdel Baki, A. (2015). Understanding process in group cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12039

- Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

- Liu, C., Wang, L., Qi, R., Wang, W., Jia, S., Shang, D., Shao, Y., Yu, M., Zhu, X., Yan, S., Chang, Q., & Zhao, Y. (2019). Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among doctoral students: the mediating effect of mentoring relationships on the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 195–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S195131

- Mancini, M. A. (2007). The role of self–efficacy in recovery from serious psychiatric disabilities: A qualitative study with fifteen psychiatric survivors. Qualitative Social Work, 6(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325007074166

- McDougall, M. A., Walsh, M., Wattier, K., Knigge, R., Miller, L., Stevermer, M., & Fogas, B. S. (2016). The effect of social networking sites on the relationship between perceived social support and depression. Psychiatry Research, 100(246), 223–229.

- Mladenovic, A. B., Wozniak, L., Plotnikoff, R. C., Johnson, J. A., & Johnson, S. T. (2014). Social support, self‐efficacy and motivation: a qualitative study of the journey through HEALD (Healthy Eating and Active Living for Diabetes). Practical Diabetes, 31(9), 370–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pdi.1905

- Murphy, R., Cooper, Z., Hollon, S. D., & Fairburn, C. G. (2009). How do psychological treatments work? Investigating mediators of change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.001

- Newman, D., O'Reilly, P., Lee, S. H., & Kennedy, C. (2015). Mental health service users' experiences of mental health care: an integrative literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 171–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12202

- Nguyen, W., Ownsworth, T., Nicol, C., & Zimmerman, D. (2020). How I See and Feel About Myself: Domain-Specific Self-Concept and Self-Esteem in Autistic Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 913. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00913

- Nolan, P., Bradley, E., & Brimblecombe, N. (2011). Disengaging from acute inpatient psychiatric care: a description of service users' experiences and views. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(4), 359–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01675.x

- Ogundare, T., Onifade, P. O., Ogundapo, D., Ghebrehiwet, S., Borba, C. P. C., & Henderson, D. C. (2021). Relationship between quality of life and social integration among patients with schizophrenia attending a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 30(6), 1665–1674. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02764-x

- Olsen, C. F., Telenius, E. W., Engedal, K., & Bergland, A. (2015). Increased self-efficacy: The experience of high-intensity exercise of nursing home residents with dementia - A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 379–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1041-7

- Palumbo, C., Volpe, U., Matanov, A., Priebe, S., & Giacco, D. (2015). Social networks of patients with psychosis: a systematic review. BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1528-7

- Pomare, C., Long, J. C., Churruca, K., Ellis, L. A., & Braithwaite, J. (2019). Social network research in health care settings: design and data collection. Social Networks, 69, 14-21.

- Pruessner, M., Iyer, S., Faridi, K., Joober, R., & Malla, A. (2011). Stress and protective factors in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis, first episode psychosis and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Research, 129(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.022

- Rehm, J., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

- Revelle, W. R. (2017). psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research.

- Richardson, T. M., Friedman, B., Podgorski, C., Knox, K., Fisher, S., He, H., & Conwell, Y. (2012). Depression and its correlates among older adults accessing aging services. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107e50

- Robins, R. W., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 158–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00353.x

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Measures Package, 61(52), 18.

- Saltzman, K. M., & Holahan, C. J. (2002). Social support, self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.21.3.309.22531

- Sampson, M., Mauldin, R. L., & Yu, M. (2021). Reducing depression among mothers in a residential treatment setting: building evidence for the PST4PPD intervention. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2020.1832644

- Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., Cornwell, E. Y., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Madsen, K. R., & Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62–e70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0

- Sowislo, J., & Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

- Soysa, C. K., & Wilcomb, C. J. (2015). Mindfulness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Mindfulness, 6(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0247-1

- Steigen, A. M., & Bergh, D. (2019). The Social Provisions Scale: psychometric properties of the SPS-10 among participants in nature-based services. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(14), 1690–1698. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1434689

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

- Strobl, C., Malley, J., & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016973

- Tew, J., Ramon, S., Slade, M., Bird, V., Melton, J., & Le Boutillier, C. (2012). Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: a review of the evidence. British Journal of Social Work, 42(3), 443–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr076

- Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

- Tian, L., Liu, B., Huang, S., & Huebner, E. S. (2013). Perceived social support and school well-being among Chinese early and middle adolescents: The mediational role of self-esteem. Social Indicators Research, 113(3), 991–1008. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0123-8

- Torrey, W. C., Mueser, K. T., McHugo, G. H., & Drake, R. E. (2000). Self-esteem as an outcome measure in studies of vocational rehabilitation for adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 51(2), 229–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.229

- Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive Questions in Surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859

- Tracy, E. M., & Abell, N. (1994). Social network map: Some further refinements on administration. Social Work Research, 18(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/18.1.56

- Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., & Robins, R. W. (2013). Development of self-esteem. In Virgil Zeigler-Hill (Ed.). Self-esteem, 60–79. New York: Psychology Press.

- Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Giacco, D., Forsyth, R., Nebo, C., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2017). Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1451–1461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

- Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

- Williams, E., Dingle, G. A., Jetten, J., & Rowan, C. (2019). Identification with arts‐based groups improves mental wellbeing in adults with chronic mental health conditions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12561

- Windgassen, S., Goldsmith, K., Moss-Morris, R., & Chalder, T. (2016). Establishing how psychological therapies work: the importance of mediation analysis. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 25(2), 93–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124400

- Wright, I., Travers-Hill, E., Gracey, F., Troup, J., Parkin, K., Casey, S., & Kim, Y. (2020). Brief psychological intervention for distress tolerance in an adult secondary care community mental health service: an evaluation. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13. E50.

- Yalom, I., & Rand, K. (1966). Compatibility and cohesiveness in therapy groups. Archives of General Psychiatry, 15(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1966.01730150043007

- Zhang, Y., & Jin, S. (2016). The impact of social support on postpartum depression: The mediator role of self-efficacy. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 720–726. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314536454

- Zhang, Z., & Yuan, K.-H. (2018). Practical statistical power analysis using Webpower and R. Isdsa Press.