Abstract

Background

Research has indicated that having financial difficulties may increase mental health problems and prevent recovery when receiving psychological treatment. A combined approach within the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service could help clients by tackling their financial difficulties alongside supporting their mental health.

Aims

We aimed to explore the experiences and views of a potential combined intervention by speaking to IAPT service users who have/had experiences of money worries, as well as IAPT therapists and Citizen’s Advice (CA) money advisers.

Method

We conducted online semi-structured interviews with 16 IAPT service users, 14 IAPT therapists/practitioners, and 6 CA money advisors. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically.

Results

Themes discussed including the impact of money worries and mental health, the benefits of a combined intervention, how and when it should be introduced to clients and delivered, and how information should be shared between the services. It was felt by most participants that such an intervention would improve mental health and provide a more holistic service with a better referral pathway.

Conclusions

Our findings provide a blueprint for a combined money advice and psychological therapy service within IAPT, which both service users and staff identified would be beneficial.

Keywords:

Financial difficulty is a rapidly increasing concern for UK households. The Office of National Statistics (ONS, Citation2019) reported a 9% increase in average household debt between 2016 and 2018, with less wealthy households being disproportionately affected. In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic these figures are expected to rise even more, with increased numbers of job losses and financial change and uncertainty for many (Patel et al., Citation2020).

At an individual level, the effect household financial difficulty has on mental health and wellbeing is of concern (Fitch et al., Citation2011 ; Holkar & Mackenzie, Citation2016; Jenkins et al., Citation2008; Sweet et al., Citation2013), as the consequences of debt can lead to suicidal behaviours for those unable to manage repayments (Richardson et al., Citation2013; Hintikka, Citation1998; Wong et al., Citation2008). The evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship, with difficulty repaying debts predicting the onset of common mental disorders (CMDs), and although CMDs were not associated with acquiring new debts, they were associated with ongoing difficulties in repaying them (Have et al., Citation2021). This is mirrored in a Money and Mental Health Policy Institute (MMHPI) report where 86% of people from their research community felt that their finances had affected their mental health, and 72% reported that their mental health problem had made their financial difficulties worse (Acton, Citation2016). The UK mental health charity Mind (Citation2011) suggests several reasons for this, including barriers such as understanding information, asking for help, avoiding opening important letters and emails, and spending more to cope with overwhelming emotions.

The Covid-19 pandemic not only increased financial uncertainty, but is also associated with increasing mental health difficulties (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, Citation2020; Jia et al., Citation2020; Pierce et al., Citation2020; White & Boor, Citation2020). According to data from NatCen (Citation2021), individuals seeking help for their finances reported a significant increase in poor mental health since the beginning of the pandemic, and those struggling financially before the pandemic were particularly vulnerable. Similarly, ONS (Citation2021) reported an increase from 21% of people who were unable to afford an unexpected expense experiencing depressive symptoms before the pandemic, to 35% during. This was significantly larger than the rise in depressive symptoms from 5% to 13% of people who indicated they could afford an unexpected expense.

Given the link between financial difficulties and mental health, dealing with clients’ financial problems should not only provide more holistic care but also increase treatment benefits. For example, there is evidence to suggest that individuals with depression are 4.2 times more likely to still be experiencing symptoms 18 months after treatment if they also have financial difficulties (Skapinakis et al., Citation2006). Clients also report that they are unable to raise financial difficulties with their therapists, and very few are referred by their therapists to external debt agencies for support when they do (Acton, Citation2016). However, receiving money and debt advice can have a positive effect on symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as helping clients feel more in control, less stressed, and improving sleep (O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

This combined approach to mental health support and money advice has been implemented in a number of different services with promising initial results. For example, combined money advice with mental health support was set up by Mental Health UK. This Mental Health and Money Advice service offers online support as well as telephone support, which is available on referral only with a specialist caseworker. In an independent review of the service, clients using the advice line demonstrated significant improvements in wellbeing and confidence in managing their money (Robotham et al., Citation2019). A key recommendation from the report highlights the need to continue the partnership between referring organisations and the service, to ease the referral process for clients, and widening the service’s audience to primary care settings also. Additionally, a trial of an intervention that offered individuals attending hospital emergency departments with self-harm or emotional distress, due to money worries, one-to-one sessions with a mental health worker was shown to be both feasible and acceptable (Barnes et al., Citation2018). These mental health workers specifically helped participants create support plans, interpret letters, connected them with community resources, and gave welfare benefit advice. Some of the benefits reported included the resolution of specific financial difficulties and being able to access support at a time of high need. Introducing a combined intervention within primary care mental health services may support more people earlier, before mental health symptoms become severe (Evans, Citation2018).

In the UK, the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) offers stepped care cognitive behavioural based psychological therapies in the National Health Service (NHS), offering recommended treatments for the management of mild to moderate anxiety and depression (e.g. NICE, Citation2009, Citation2011; NHS, Citation2019). These include Step 2 care, which offers low-intensity treatment in the form ofself-guided help, and Step 3 care, which offers high-intensity treatment in the form of one-to-one support with a trained therapist for those who have not responded to low-intensity interventions. Although reliable recovery rates reached 40% in the first two years (Clark, Citation2011), increasing this rate has been slow and is yet to exceed the government’s initial 50% target (NHS, Citation2020). As clients’ financial difficulties may be preventing higher recovery rates, MMHPI calculated the odds ratios for those with and without financial difficulties using IAPT. They predicted that recovery rates could be as low as 22% for those with depression and financial difficulties, compared to 55% for those without financial difficulties (Acton, Citation2016). The report recommended joining up mental health and debt services for the development of more accessible referral pathways. Other research also strongly emphasises the importance of a collaborative approach in tackling mental health service users’ problem debt, with therapists working alongside debt advisors, rather than just referring on to outside agencies (Fitch et al., Citation2011). A combined approach within IAPT could help clients reach recovery by tackling their practical financial difficulties alongside supporting their mental health.

The aim of the current research is to develop a combined intervention between IAPT and Citizen’s Advice (CA) that can support clients with mental health and money worries together. The first stage of development was too explore the experiences and views of a potential combined approach by asking IAPT service users who have/had experience of financial difficulty, as well as money advisors from CA and psychological therapists from IAPT. We examine whether joining up of services would be beneficial, what key outcomes could be achieved, and the optimal timing and format of that service. Understanding these different views could then lead to the design of a combined intervention that provides both financial advice and psychological therapy.

Method

Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit IAPT service users, IAPT therapists, and CA advisors, with recruitment ending when we had reached data saturation (no new themes emerging in our analysis) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We initially estimated that 12 interviews would be sufficient for analysis of service users, and that 10 would be sufficient for analysis of staff. Assessing the information power of our sample, the study’s aims were narrow and the sample highly specific to users of IAPT with money worries and the staff supporting them. Additionally, the study was based on established theories and evidence pertaining to the effect of money worries on mental health and the joining up of services, and the interviews were conducted by two experienced researchers, providing strong dialogues. Therefore, a smaller sample size was required, and our estimates were deemed appropriate (Malterud et al., Citation2016). Service users with experience of IAPT and problem debt were recruited via the MMHPI’s research community or via local IAPT services (n = 16; see ). IAPT therapists (n = 11) were recruited and, following those interviews, 3 IAPT employment advisors were recruited, as their importance was stressed. The majority of IAPT therapists interviewed were Step 3 high-intensity practitioners (n = 9), and therefore worked with client’s whose conditions were mild to moderately severe and had not responded to Step 2 low-intensity interventions. For the money advisors we recruited from the local CA services (n = 6). Staff participant data is shown in .

Table 1. Service user participant demographics.

Table 2. Staff participant demographics.

Ethics approval for non-clinical participants was granted through King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (HR-20/21-21720). For clinical participants we received NHS ethics approval (295761). All participants provided written informed consent allowing us to use their data and were offered £30 for their time (£15 for an interview/focus group and £15 for member feedback).

Procedure

CA advisors were interviewed as a group, with the rest being one-to-one interviews, and all taking place online over Microsoft Teams. Discussions were semi-structured around a service user or staff topic guide based on previous literature, and included experiences of financial difficulty, mental health, accessing support and benefits of a combined approach (see Supplementary Materials 1 & 2). Each interview/focus group was recorded and transcribed, and summaries provided over email as part of a member checking process.

Analysis

Transcripts and research notes on the summaries were imported into NVivo 12 software and two researchers (H.B. and J.E.) independently analysed the data using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) thematic analysis method. This involved initial familiarization of the data followed by data coding, and the generation of themes. The themes from both independent researchers were combined and reviewed for discrepancies by a third researcher (N.B.).

Results

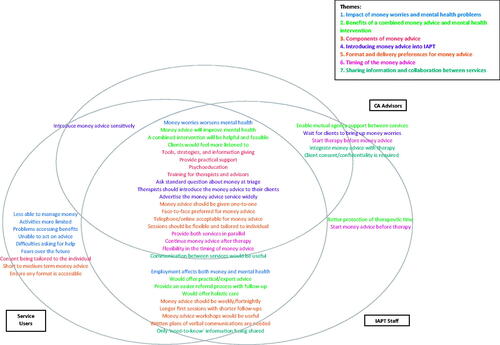

Seven broad themes were discussed during the interviews by both service users and IAPT/CA staff, providing a framework of subthemes. Whilst many overlapped, there were some subthemes endorsed more by a specific group (see ). Similarities and differences are described in more detail below (see Supplementary Material 3 for frequencies). Examples of short quotes given for service users and staff (CA advisors and IAPT staff) are provided separately in and .

Table 3. Example quotes from interviews with service user participants.

Table 4. Short example quotes from interviews with CA advisors and IAPT therapists.

Impact of money worries and mental health problems

Most participants reported that money worries worsened mental health. For some, money worries exacerbated existing mental health problems, for others, mental health difficulties led to increased money worries. This vicious cycle led to hopelessness, and despair. IAPT staff and service users also mentioned that employment affects both money and mental health, with some being made redundant, leading to money worries, and others being unable to work due to mental health difficulties. Additionally, the service users endorsed more specific themes, including being less able to manage money, having activities more limited, problems accessing benefits, being unable to act on advice, having difficulty asking for help, and experiencing fears over the future.

Benefits of a combined money advice and mental health intervention

Many participants suggested that a benefit would be improved mental health. It was suggested that this ‘two pronged’ attack would help to avoid mental health crises and increasing debts. The majority said the combined intervention would be both helpful and feasible and that clients would feel more listened to. Both service users and IAPT staff also suggested that a combined intervention would offer practical/expert advice not currently available in IAPT, that it would provide an easier referral process with follow-up, and that it would offer holistic care too. Unique to the CA and IAPT staff was the suggestion that it would enable mutual agency support between the services, providing a more ‘joined-up’ service, and IAPT staff also felt it would mean better protection of therapeutic time.

Components of money advice

One of the most suggested components of money advice was tools, strategies, and information giving, e.g. helping clients maximise income (e.g. applying for welfare benefits), prioritise re-payments, and manage budgets. Many also suggested it should provide practical support, such as advocating for clients, psychoeducation, such as supporting clients to understand psychological aspects of spending, and training for therapists and advisors, to ensure staff are equipped to support clients with both money worries and mental health problems. Service users also emphasised that content being tailored to the individual was an important aspect of the money advice service.

Introducing money advice into IAPT

The main suggestion for introducing the money advice to IAPT clients was to use a standard question at triage, as many other closed questions were asked at this point to help practitioners’ direct clients to the most appropriate treatment. Many also suggested that the IAPT therapist should introduce the money service to their clients, whilst it was also suggested that IAPT should advertise the money advice service widely, to ensure clients are aware they can access it during their therapy. Both service users and CA advisors emphasised that IAPT should introduce money advice sensitively, e.g. avoiding triggering words like ‘debt’. Additionally, both CA advisors and IAPT staff suggested it might be better to wait for clients to bring up money worries before introducing the service, to ensure they’re ready to address their money problems.

Format and delivery preferences for money advice

Most participants suggested one-to-one sessions would be best, as money issues can be a personal topic. Face-to-face was the most suggested method of delivery, as this enabled better communication and sharing of documents. However, since Covid-19 restrictions, IAPT services have been delivered via telephone and online, and so many also said this was feasible and easier to access, although, some service users found the telephone overwhelming. It was important to most participants that any approach to the format and delivery of the service should be flexible and tailored to the individual, as everyone’s situation is unique. Both service users and IAPT staff also suggested money advice should be weekly/fortnightly, and that longer first sessions with shorter follow-ups were preferred. Money advice workshops would be useful too, to cover more general topics and provide peer support. Both also suggested that written plans of verbal communications are needed, to help clients process and follow complex information. Only service users suggested the service could offer short to medium term money advice and emphasised that it was important to ensure any format is accessible, e.g. ensuring all clients can attend sessions and that they’re adapted for learning disabilities.

Timing of the money advice

Many participants said that money advice should be delivered in parallel with therapy, so both services could support each other and offer holistic care. A key suggestion was also that advisors should continue money advice after therapy, as money difficulties may take longer to resolve than the typical number of IAPT sessions would allow (between 6 and 12). It was important that there should be flexibility in the timing of money advice, to allow clients to engage with the service at a time best for them. IAPT staff and CA advisors both endorsed the idea that it might be beneficial to start therapy before money advice, so clients are in a better place to act on advice, although IAPT staff appeared to be more likely to endorse the suggestion that it would be best to start money advice before therapy instead. The key reason for this suggestion was that money worries often took up therapy time and exacerbated mental health problems.

Sharing information and collaboration between services

Collaboration between the IAPT practitioner and money advisor was considered useful by most participants. This meant that therapists and advisors knew whether the client was engaging, and it eased the burden on clients to communicate the same information twice. Both CA advisors and IAPT staff suggested too that it would be helpful to integrate money advice with therapy, e.g. having staff with dual roles in IAPT, and that client consent/confidentiality is required for any information sharing between services. Lastly, both service users and IAPT staff also emphasised the importance of only ‘need-to-know’ information being shared’, e.g. an outline of the client’s condition and difficulties rather than detailed notes.

Discussion

Many views and suggestions were expressed by both service users and service staff (CA advisors and IAPT staff) and echoed those discussed in previous literature. For example, most participants discussed worsening of mental health problems as both the result of increasing money worries and as a cause, suggesting a bidirectional relationship (Have et al., Citation2021). Both service users and IAPT staff also discussed employment issues and problems accessing benefits, which exacerbated both mental health and money difficulties. 300,000 people with long-term mental health conditions lose jobs each year (Farmer & Stevenson, Citation2017), with a large majority feeling pressurised to attend work even when unwell (Nikki & Braverman, Citation2018), and that accessing benefits can be extremely difficult when mental health problems lead to problems in motivation, energy, and processing complex information (Bond, Citation2021). Service users reflected on several other more specific consequences, including being less able to manage money, having their activities limited, being unable to act on and ask for help, and fears over their future. This highlights the issues both service users and therapists may face when tackling both mental health issues and money worries together, particularly if clients do not feel they can even tell their therapists in the first place (Acton, Citation2016). Given the stigma associated with both mental health difficulties and financial difficulties (Andelic et al., Citation2019; Bharadwaj et al., Citation2017), these findings are not surprising.

Most participants felt a combined intervention would improve mental health and be both helpful and feasible. This combined intervention would offer practical and expert advice, more holistic care, and would improve the referral process and follow-up to money advice services, which has previously been reported as being problematic (Bond & Holkar, Citation2020; Evans, Citation2018). Both CA advisors and IAPT staff emphasised that the combined intervention would protect therapeutic time, as often money worries became a priority in discussions during IAPT sessions, and would also enable mutual agency support between both services.

Our data builds on previous reports and provides a blueprint for what a new combined money advice and psychological therapy service, specifically in IAPT, should look like. Within the theme framework participants also discussed how money advice should be introduced, how it should be delivered, the timing of its delivery, and collaboration between the two services. Most suggested a standard question about money worries during IAPT triaging. As previously reported by MMHPI, this would help ‘nudge’ clients who feel embarrassed to raise such issues (Acton, Citation2016), particularly as service users suggested that they often found it difficult to raise their money worries in therapy. Therapists should introduce money advice to their clients once therapy has started, and this service should be advertised widely. It will be critical that a combined intervention prompts clients throughout their IAPT treatment to disclose any money worries, and clients are aware of what they can access from their first point of contact with the service. The benefit of this approach will be that as well as clients feeling less embarrassed to raise money worries, it may also help the therapist to work with the clients’ feelings of guilt and shame around their money worries to enable them to accept that money advice support and to normalise having such difficulties. Money advice sessions should be one-to-one and clients should be able to choose how they would prefer to attend these sessions, with the option of face-to-face, online, and telephone. It was largely agreed by service users and IAPT staff that session duration and frequency could be much more flexible than IAPT currently allows. For example, whilst a longer first session may be needed to gather information, shorter follow-ups could be given, and clients could be seen every other week to enable more time to act on advice. Service users and IAPT staff suggested that the combined service needs accessible and written plans of verbal communications will help clients to process instructions.

In terms of the timing of a money advice service within IAPT, providing both services in parallel is preferable as it allows for mutual agency support and the tackling of both issues more holistically. Money advice should also continue after IAPT therapy is completed, as these issues will take longer to resolve. Generally, the money advice service needs to be flexible and to adaptable to each client. Client choice in the services they receive is an important factor for many and improves engagement (Laugharne & Priebe, Citation2006). Lastly, the benefit of a combined service will be the sharing of information and collaboration between the two services. As MMHPI previously reported, this will reduce burden on participants to retell their difficulties to multiple agencies (Acton, Citation2016). However, any sharing of information will need to ensure client’s consent and confidentiality, and that only ‘need-to-know’ information is shared, to ensure client privacy.

Limitations

This study provides rich data but the sample was not very diverse. Those from Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities are disproportionately affected by socioeconomic difficulties and access to mental health services, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic (Smith et al., Citation2020), so we lack their important perspective. All our service users had access to technology in order to participate in the interviews and as digital poverty is a concern many people may struggle to afford laptops and mobile phones to engage online. Lastly, it is important to note that the majority of our IAPT therapists were high-intensity (Step 3) therapists. Given that the support given in Step 2 care differ in terms of time spent with clients and the issues dealt with, our recommendations may not be generalisable to those working with the lower intensity clients who they would see less regularly and for shorter periods of time.

Conclusion

The current study explored the views of IAPT service users, CA advisors, and IAPT staff on the effects of financial difficulties and mental health problems, and a combined service that could tackle both in tandem. From our interviews we identified a link between mental health problems and financial difficulties so a service that could combine support for both aspects, and which was flexible to clients’ needs, could help improve recovery in IAPT. What remains to be determined is how acceptable and feasible such a combined service within IAPT would be.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the expert input of the Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre’s “Service User Advisory Group” (SUAG) in the development of this study’s protocol. The authors also acknowledge the advice and guidance of our Steering Group and the IAPT and Citizen’s Advice service directors and staff who assisted us in the execution of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available due to [restrictions e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acton, R. (2016). The Missing Link. http://www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Singles-MMH_3273_Our_Report_LiveCopy_DIGITAL_SINGLE.pdf

- Andelic, N., Stevenson, C., & Feeney, A. (2019). Managing a moral identity in debt advice conversations. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(3), 630–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12303

- Barnes, M. C., Haase, A. M., Scott, L. J., Linton, M.-J., Bard, A. M., Donovan, J. L., Davies, R., Dursley, S., Williams, S., Elliott, D., Potokar, J., Kapur, N., Hawton, K., O'Connor, R. C., Hollingworth, W., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2018). The help for people with money, employment or housing problems (HOPE) intervention: pilot randomised trial with mixed methods feasibility research. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4, 172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-018-0365-6

- Bharadwaj, P., Pai, M. M., & Suziedelyte, A. (2017). Mental health stigma. Economics Letters, 159, 57–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.06.028

- Bond, N. (2021). Set up to Fail. https://www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/MMH-Set-up-To-Fail-Report-WEB.pdf

- Bond, N., & Holkar, M. (2020). Help Along the Way. https://www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Help_Along_the_Way.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Clark, D. M. (2011). Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: The IAPT experience. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 318–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2011.606803

- Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

- Evans, K. (2018). Treating financial difficulty - the missing link in mental health care? Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(6), 487–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1520972

- Farmer, P., & Stevenson, D. (2017). Thriving at work. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/658145/thriving-at-work-stevenson-farmer-review.pdf

- Fitch, C., Hamilton, S., Bassett, P., & Davey, R. (2011). The relationship between personal debt and mental health: a systematic review. Mental Health Review Journal, 16(4), 153–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13619321111202313

- Have, M. T, Tuithof, M., Van Dorsselaer, S., De Beurs, D., Jeronimus, B., De Jonge, P., & De Graaf, R. (2021). The Bidirectional Relationship Between Debts and Common Mental Disorders: Results of a longitudinal Population-Based Study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 48(5), 810–820. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01131-9

- Hintikka, J., Kontula, O., Saarinen, P., Tanskanen, A., Koskela, K., & Viinamäki, H. (1998). Debt and suicidal behaviour in the Finnish general population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 98(6), 493-6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10125.x

- Holkar, M., & Mackenzie, P. (2016). Money of your Mind. https://www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Money-on-your-mind-full-report.pdf

- Jenkins, R., Bhugra, D., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Farrell, M., Coid, J., Fryers, T., Weich, S., Singleton, N., & Meltzer, H. (2008). Debt, income and mental disorder in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 38(10), 1485–1493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707002516

- Jia, R., Ayling, K., Chalder, T., Massey, A., Broadbent, E., Coupland, C., & Vedhara, K. (2020). Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open, 10(9), e040620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040620

- Laugharne, R., & Priebe, S. (2006). Trust, choice and power in mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(11), 843–852. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0123-6

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- MIND (2011). Still in the red: Update on debt and mental health. https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/4348/still-in-the-red.pdf

- NatCen (2021). Finances and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Available at: https://www.natcen.ac.uk/our-research/research/finances-and-mental-health-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ [Accessed 14/07/21].

- NHS (2019). The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Manual. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/the-iapt-manual-v5.pdf

- NHS (2020). Psychological Therapies: reports on the use of IAPT services, England April 2020 Final including reports on the IAPT pilots. In Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-report-on-the-use-of-iapt-services/april-2020-final-including-reports-on-the-iapt-pilots/outcomes [Accessed 14/07/21].

- NICE (2009). Depression in adults: recognition and management (NICE Guideline CG90). In Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/chapter/Context#stepped-care [Accessed 14/07/21].

- NICE (2011). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management (NICE guideline CG113). In Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113 [Accessed 14/07/21].

- Nikki, B., & Braverman, R. (2018). Too Ill to Work, too Broke Not to. https://www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Too-ill-to-work-too-broke-not-to-1.pdf

- O’Brien, C., Willoughby, T., & Levy, R. (2014). The Money Advice Service Debt Advice Review 2013/14. https://mascdn.azureedge.net/cms/optimisa-final-quant-report-jul-2014.pdf

- Office for National Statistics (2021). Personal and economic well-being in Great Britain: January 2021. In Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/personalandeconomicwellbeingintheuk/january2021 [Accessed 14/07/21].

- Office of National Statistics (2019). Household debt in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018. In Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/householddebtingreatbritain/april2016tomarch2018 [Accessed 14/07/21].

- Patel, J. A., Nielsen, F. B. H., Badiani, A. A., Assi, S., Unadkat, V. A., Patel, B., Ravindrane, R., & Wardle, H. (2020). Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health, 183, 110–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006

- Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10) https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

- Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2013). The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1148–1162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009

- Robotham, D., Andleeb, H., Couperthwaite, L., & Evans, L. (2019). Evaluation of the Mental Health and Money Advice Service. https://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MHUK-evaluation_Final-report.pdf

- Skapinakis, P., Weich, S., Lewis, G., Singleton, N., & Araya, R. (2006). Socio-economic position and common mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 189(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.014449

- Smith, S., Gilbert, S., Ariyo, K., Arundell, L.-L., Bhui, K., Das-Munshi, J., Hatch, S., & Lamb, N. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(7), e40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30250-9

- Sweet, E., Nandi, A., Adam, E. K., & McDade, T. W. (2013). The high price of debt: Household financial debt and its impact on mental and physical health. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 91, 94–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.009

- White, R. G., & Boor, C. V. D. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. BJPsych Open, 6(5), e90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.79

- Wong, P. W. C., Chan, W. S. C., Chen, E. Y. H., Chan, S. S. M., Law, Y. W., & Yip, P. S. F. (2008). Suicide among adults aged 30–49: A psychological autopsy study in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-147