Abstract

Background

Self-harm amongst young people in the United Kingdom is higher than in other European countries. Young people who self-harm are often reluctant to seek professional help, turning increasingly to the internet for support, including online forums. There are concerns about misinformation or harmful content being shared, potentially leading to self-harm contagion. Moderation of online forums can reduce risks, improving forum safety. Moderation of self-harm content, however, is an under-researched area.

Aims

Using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), this study examines the barriers and enablers to moderation of self-harm content and suggests behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to address barriers.

Method

Qualitative interviews with 8 moderators (of a total of 16) from the UK’s leading young people’s support service for under 25s, The Mix, were conducted.

Results

Thematic analysis identified eleven enablers, four barriers and one both an enabler and a barrier. Barriers included emotional exhaustion, working with partial information, access to timely support, vagueness within the guidelines and influence of community users. BCTs selected included increasing social support through a moderation buddy.

Conclusions

Optimisation strategies focus on increasing the support and level of information available to moderators and could be considered by other organisations providing similar services.

Self-harm amongst young people in the UK is higher than in other European countries, with an estimated 14% of young people having self-harmed (McManus et al., Citation2016). Self-harm can include poisoning, cutting, excessive alcohol consumption, illegal drug use and hitting or burning (Burton, Citation2014). It is a recognised risk factor for suicide and has been identified by the UK government as a priority for action (Department of Health, Citation2017).

Evidence suggests that young people who self-harm and feel the most need for support are least likely to seek it (Evans et al., Citation2005) with only around a third reporting receiving professional help (McManus et al., Citation2016). Young people are increasingly turning to the internet for mental health support (Marchant et al., Citation2017), including online forums, which offer anonymity and feel less judgemental (Jones et al., Citation2011; Whitlock et al., Citation2006). Online forums generally involve asynchronous interaction between participants using self-chosen usernames, operating within published guidelines (Hanley et al., Citation2019), reading and responding to messages (posts) displayed to all users (Smithson et al., Citation2011). Accessing online mental health forums can lead to other forms of help-seeking, with users encouraging each other to seek professional help (Kendal et al., Citation2017). Moderation involves staff, volunteers or community members, providing support, signposting, mediating discussions and removing or editing users’ posts as appropriate. Moderation of online spaces for self-harm is considered important in maximising useful content and minimising risk (Samaritans, Citation2020).

Despite its importance, however, research on moderation is sparse (Smedley & Coulson, Citation2017), with no research exploring the experiences and practices of moderators of self-harm content (Perry et al., Citation2021). This is problematic because understanding the processes through which moderators support vulnerable communities could help identify potential improvements (Perry et al., Citation2021). To address the gap, this qualitative study uses the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Michie et al., Citation2014), a theoretically-based and systematic approach, to analyse moderation of self-harm content and suggest evidence-based optimisation strategies.

Background

Existing studies examining moderation of online mental health forums are not theoretically-based and focus on describing the tasks and impact of moderation. For example, a thematic analysis of online health forums identified four common moderation activities: supportive tasks such as suggesting coping strategies to users, sharing moderators’ own experiences, making announcements such as advertising events and administrative tasks including enforcing forum rules (Smedley & Coulson., 2017). Hanley et al. (Citation2019) highlight moderators as an important source of peer-support; helping users engage with services and protecting them from misinformation, arguing that, where moderators are skilled, with a high level of oversight, services are likely to be safer and more beneficial to users. Ineffective moderation risks harming forum culture and discussion quality (Huh et al., Citation2016).

Behaviour Change Wheel

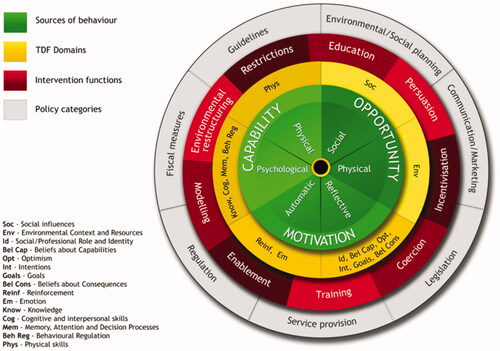

The BCW (see ) is a comprehensive behaviour change framework, synthesised from 19 existing frameworks (Michie et al., Citation2011). It is used to analyse behaviour and support the development and evaluation of behaviour change interventions (Michie & West, Citation2013). The Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model is at the core of the BCW and allows categorisation of barriers and enablers of behaviour change in terms of capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social) and motivation (reflective and automatic). The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) adds a level of granularity to COM-B (Atkins et al., Citation2017), breaking the components down further, into 14 domains (see ). Psychological Capability includes knowledge; cognitive and interpersonal skills; memory, attention and decision making and behavioural regulation. Reflective Motivation includes social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capability, optimism, intentions, goals and beliefs about consequences. Automatic Motivation includes reinforcement and emotions. Social Opportunity includes social influences and Physical Opportunity includes environmental context and resources. Physical Capability includes physical skills. The outer layers of the BCW offer nine intervention functions supported by seven policy categories, which map to COM-B components and TDF domains to inform behaviour change strategies. Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) extend the BCW, providing the smallest level of “active ingredients” for interventions (Cane et al., Citation2015). The Theory and Technique Tool shows the connections, identified through evidence and expert consensus, between TDF domains and BCTs (Human Behaviour Change Project, Citation2019).

Present study

This qualitative study used the BCW framework to analyse the barriers and enablers to moderation of self-harm posts on an online forum hosted by young persons’ charity, The Mix, which provides online and telephone mental health support to 16- to 25-year-olds. Two research questions were examined: (1) What are the barriers and enablers to moderation of self-harm posts on an online discussion forum for young people, categorised by COM-B components and TDF domains? and (2) How can moderation of self-harm be optimised by identifying possible intervention functions and BCTs to address barriers?

Method

Sample and recruitment

Data were gathered using a convenience sample of 8 moderators (5 staff and 3 volunteers) from a total of The Mix’s 16 moderators. On average, participants were 26 years old and had moderated with The Mix for over 2 years. Initial contact with moderators was made by The Mix, with those interested asked to contact the researcher directly to preserve confidentiality. Potential participants were sent electronic participant information and consent forms. Once consent was received interviews were arranged and conducted via MS Teams, offering video or audio only options. No participants withdrew through the process. Participation was compensated through a £25 voucher.

Ethics

Low-risk approval was obtained through University College London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee (reference 20293/001 on 28/04/2021).

Interview procedures

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews, of 60 to 90 minutes, recorded using Microsoft Stream and transcribed verbatim before deletion. Questions were based on COM-B and TDF domains with additional, broader questions added allowing participants to give freer responses (McGowan et al., Citation2020). Questions included “How do you think moderation helps people who self-harm?” (beliefs about consequences), “How do other people influence how you moderate self-harm posts?” (social influences) and “Are there any other factors that affect your moderation of self-harm posts?” (open question).

Data analyses

Thematic Analysis, using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-phase process, was used in line with similar studies (Richiello et al., Citation2022). Initially, barriers and enablers were coded deductively into themes using both COM-B and TDF frameworks. A second researcher carried out a reliability check on one transcript and discrepancies were discussed until agreement was reached. Data were then recoded inductively, providing more specificity and capturing any data not fitting within COM-B or TDF (McGowan et al., Citation2020). Three levels of themes were generated based on the prevalence and relative emphasis placed on a subject by participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). COM-B provided overarching themes, TDF secondary themes and additional sub-themes were derived inductively.

Barriers to moderation were then mapped, according to their corresponding secondary TDF theme, to the relevant intervention functions, using BCW guidance, and BCTs were identified using the Theory and Technique Tool. This provided a short-list of evidence-based potential intervention functions and BCTs. The APEASE (Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness, Affordability, Spill-over and Equity) criteria (Michie et al., Citation2014) were assessed for each intervention function and BCT to identify the most promising. Finally, a literature search identified specific intervention strategies to deliver each intervention function and BCT to optimise moderation.

Results

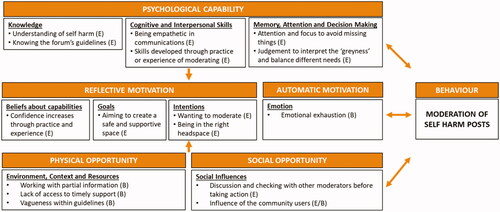

Sixteen inductively derived sub-themes were generated and mapped to overarching COM-B themes and secondary TDF themes (see ). Sub-themes including eleven enablers, four barriers and one both an enabler and a barrier (see ) are described below.

Figure 2. Map of themes, indicating COM-B (overarching) themes, TDF (secondary) themes and inductive sub-themes. Overarching COM-B themes are indicated by shaded boxes, TDF secondary themes by bold, underlined text and inductive sub-themes are indicated by bullet points. Letters in brackets indicate whether each sub-theme was identified overall as an Enabler (E), a Barrier (B) or a combination of Enabler and Barrier (E/B). Arrows show COM-B interactions.

Table 1. Sub-themes identified as barriers or enablers with a description of each sub-theme.

Psychological Capability

Understanding of self-harm

All participants felt that having a detailed understanding of self-harm was an enabler to moderation. Such knowledge included understanding the spectrum of self-harm, the language around self-harm, and the possible “triggers” and causes of self-harm. “Understanding the triggers, understanding the language around it, understanding what causes somebody to self-harm, I think that's quite important” (S2). Often this knowledge came from direct experience, which participants felt particularly helped their understanding: “I don't think unless you've experienced it or have worked with people you'd really understand” (V3).

Knowing the forum’s guidelines

Staff, in particular, saw awareness and knowledge of the online forum’s guidelines as an important enabler of moderation, frequently referencing the guidelines during their interviews. S2 believed that moderation was made easier by “all the staff (having) the same understanding of the guidelines”. Staff moderators explained how the guidelines helped achieve their aims of keeping the forum safe and providing consistency. In contrast, volunteers did not always seem to share this recognition of the importance of the guidelines in their moderation, as explained by V3, “in all honesty I don't have any guidelines in my head that I'm sort of referring to when I'm moderating”.

Being empathetic in communications

Given the text-based nature of the forum, showing empathy through written communication was seen by all participants as a skill that enabled moderation: “being able to kind of relate to people and their situation and embody that approach, through their written communication is really, really important” (S1). A number of moderators talked about personalising their written responses to users to avoid coming across as robotic or inauthentic and often used emojis to show empathy.

Skills developed through practice and experience of moderating

Although some participants mentioned training (through The Mix or, often, elsewhere) as a way of developing their skills, practice and experience were considered by all as the most effective way in becoming competent. V3 felt “You've got to have quite a bit of experience….if you haven't seen other posts, you can't really know”.V2 added, “there was a lot of practice shifts first which was great”. This practice allowed moderators to receive feedback.

Attention and focus to avoid missing things

Many participants described being observant, “having a real eagle eye about it” (V1), and paying attention to the language used in posts, to identify when a user might be struggling. They would notice subtle changes to the tone or style of messages, “reading between the lines” (S1) and responding accordingly. Some moderators were particularly focused on users who might be at risk of harm, looking out for words of concern in the title of a post and intervening quickly. Concentration was heightened by features of the environment such as the lack of face-to-face contact, requiring moderators to look for different signals, as explained by S4: “you can't see someone's body language and things, but when all you have is how they text or how they message, you pick up on that”.

Judgement to interpret the “greyness” and balance different needs

All moderators emphasised the importance of judgement in enabling moderating. This involved balancing support to individual users with the needs of the wider forum community, who may be “triggered” by what they were reading. As V3 explained, “you’ve got to know the balance between supporting the individual but also protecting the other members of the community.” In doing this, moderators needed to use interpretative skills to establish what the guidelines allowed. S1 stated, “you can't cover every eventuality with a broad set of principles. And so there is always a degree of interpretation”.

Reflective Motivation

Confidence increases through practice and experience

Most moderators felt reasonably confident moderating self-harm posts independently: “the kind of general skills and approaches that I learned by responding to those (practice posts) were applicable across the board and so I was able to go away and be a little bit more independent” (S1). This confidence developed over time, through practice and experience of moderating self-harm, as moderators had seen and dealt with most scenarios and felt clear about the action required in different situations. V3 added, “I feel like I’m quite confident now I’ve dealt with quite a few of them to understand enough”.

Aiming to create a safe and supportive space

Moderators’ goals were to ensure that the online forum was both safe and supportive for members; aiming to create a space where individuals could be given a voice, share their feelings and receive support. Volunteer moderators were particularly motivated “to support the individual as best as I can” (V3). Whilst staff moderators prioritised forum safety, ensuring that users were not put at risk by discussions that were taking place, through editing or removing posts that could risk triggering users and cause them to self-harm: “the priority is always to edit and, you know, make sure that things are safe” (S4).

Wanting to moderate

Several moderators described their intention to moderate being driven by a desire to help others. S5: “I’m sort of in this line of work ‘cause I want to help people”. For some, this desire came from a general interest in mental health, whereas others had a particular interest in self-harm, often due to their personal experiences. V3 stated: “So I was part of the community myself…. and after sort of becoming more stable, I wanted to help other people.”

Being in the right headspace

Moderators were very aware of the emotional demands of moderating self-harm. Most described moderating only if they had the energy and were in the right frame of mind. V2: “We need to be in the right headspace for it….you don't really want to be doing your shift just feeling that you need to put the time in and just get it done”. When they felt unable to moderate, they would take a break or find someone to cover their shift, recognising the demands of listening carefully and being sensitive over a long period.

Automatic Motivation

Emotional exhaustion

Moderators described finding moderating self-harm emotionally exhausting, as messages could be “shocking” (S1) and “distressing” (S3). For some moderators, self-harm was particularly difficult “cause it’s too triggering (V2)” for them. Others described dealing with a lot of self-harm posts as overwhelming, “those posts can be quite heavy and I think you can burn out quite quickly” (S5). Moderators recognised the impact that moderation could have on users and this could cause concern because: “I wouldn’t want for me to say something that then maybe set something off…that’s probably the biggest worry in responding” (V2).

Physical Opportunity

Working with partial information

The online environment meant that moderators were working with incomplete information. Even with regular users, moderators were unable to use the tone of voice or visual clues, such as body language, to understand users’ feelings and so were reliant on just text-based messages. As S1 explained: “often what people type is only kind of a fraction of maybe what's really going on”. Added to this, the forum’s guidelines meant that moderators were limited in what they could ask users, as S2 described “You can’t ask any detailed questions about the act, to assess whether or not there is a risk to life”.

Lack of access to timely support

All moderators recognised the importance of support, S1 stated: “It can be really tough, absolutely, and it's important that moderators have their own support spaces”. Whilst organisational support (e.g. clinical supervision and group chat) was helpful, the lack of timely support could be a barrier. This was particularly significant for volunteers, who could feel vulnerable when they were moderating, especially out-of-hours. As V2 said: “there's not anyone there immediately to respond to you…it's something that I struggle with”.

Vagueness within the guidelines

Although moderators generally identified being aware of the online forum’s guidelines as an enabler, there were also numerous references to the vagueness (or “greyness”) in the guidelines. Most moderators appreciated that it was impossible to cover every situation within a set of written guidelines but this resulted in gaps or ambiguity. As a result, moderators sometimes found it difficult to know what action to take. V2 explained: “you can still be left with sort of a scenario where you actually don't know what the guidelines would recommend for this case”. For example, self-harm scars were mentioned by a number of moderators as difficult to navigate because, although images of self-harm were clearly not acceptable within the guidelines, it was less clear how this applied to scars.

Social Opportunity

Discussion and checking with other moderators before taking action

All moderators identified fellow moderators as an important, positive influence. One moderator (S1) described moderation as a “collective activity that we performed as a team”. Staff and volunteer moderators described checking their intended responses to posts with colleagues before acting. Staff members usually did this through discussion at team meetings, whereas volunteers often used a group chat or moderators’ board to seek other moderators’ views. V1 explained: “you always just think if you have any, like uncertainties like oh maybe/maybe not, just always message like one of your colleagues”.

Influence of the community users

Users within the online community could be both a barrier and an enabler to moderation. Most moderators mentioned the helpful role users played in spotting posts of concern. S4 acknowledged that moderators “rely on the community members to report posts that they thought are against our guidelines”. However, users could also be a barrier, exerting pressure on moderators to moderate in a certain way. If users felt there had been any inconsistent treatment, they would point this out to moderators, occasionally in an aggressive way. This could cause moderators to doubt themselves potentially resulting in “over-moderating”. As S2 expressed: “what I don't like is when we have to over-moderate because the community is forcing us to over-moderate 'cause they're angry about it being unfair”.

Intervention functions and behaviour change techniques

Barriers to moderation were mapped to the most relevant intervention functions and BCTs using the connections between TDF domains and relevant intervention functions (within the BCW) and BCTs (as outlined in the Theory and Technique Tool). An APEASE assessment supported the final selection of suitable intervention strategies (see ).

Table 2. Barriers mapped to IFs and BCTs selected through APEASE.

Discussion

This study addresses a significant gap in the literature around the moderation of mental health related online forums (Kendal et al., Citation2017) and specifically in understanding the experiences and practices of moderators of self-harm content (Perry et al., Citation2021). Using the BCW approach, the thematic analysis identified 16 sub-themes including eleven enablers, four barriers and one both an enabler and a barrier. Enablers and barriers are discussed below, with potential BCTs highlighted to address barriers to moderation in this context.

Enablers of Self-Harm moderation

Eleven enablers to moderation were identified in this study and several support findings of previous studies. In a similar finding to Hanley et al. (Citation2019), which described moderation as a “highly-skilled role”, moderators in this study emphasised a number of psychological capabilities that enabled moderation. Webb et al. (Citation2008) describe a 2-day training programme undertaken by moderators to help them recognise and respond to harmful posts. The present study extends previous research, and addresses a significant gap in the literature (Perry et al., Citation2021), by further identifying the specific capabilities moderators rely on, such as knowledge and understanding of self-harm, awareness of relevant guidelines and cognitive and interpersonal skills including judgement, attention and empathy. These skills are important given the “complex and multifaceted decisions and interactions” of moderators (Perry et al., Citation2021, page 8) and moderators report gaining confidence through practising these skills.

Reflective Motivation was also an enabler, specifically in that moderators were driven by a desire to help, and to create a safe and supportive space for users, a feature of moderation also emphasised in Webb et al. (Citation2008). Social influences, in addition, were a key feature of this study (predominantly as an enabler), with moderators providing valuable support for each other in a similar way to Webb et al. (Citation2008) where moderators were encouraged to support each other through sharing their experiences and discussing any concerns on a dedicated online forum. Studies of online communities more broadly reinforce the finding of this study that strong connections and norms can be developed amongst online communities, despite interactions being based purely on text and image sharing (Wise et al., Citation2006). It is argued that such norms influenced forum users in this study to flag posts of concern to moderators.

Optimising moderation through addressing barriers

Emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion affected moderators’ intentions to moderate. Owens et al. (Citation2015) similarly found that mental health professionals failed to participate in an online self-harm forum because they felt overwhelmed by high volumes of self-harm posts and levels of distress amongst users. “Reduce negative emotions” is the BCT suggested to overcome emotional barriers. Although moderators described combating emotional exhaustion through self-care, additional strategies could be considered to address the barrier. For example, an intervention involving Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) showed positive impacts on anxiety and burnout of dementia healthcare workers (Montaner et al., Citation2021). Through exercises such as mindfulness and meditation, ACT aims to increase psychological flexibility, leading to improved performance, job satisfaction and mental health. It helps participants connect with the present moment, learn to understand, but not get carried away by, their emotions and tune in to their personal values. In addition, peer-consultation, a model designed to provide colleagues with a forum to share experiences and anxieties in a supportive environment, could be introduced. Moderators would be encouraged to help each other in dealing with the stressors of their roles in a problem-solving way, without the hierarchy or formality of clinical supervision (Powell, Citation1996).

Working with partial information about users

Consistent with other studies (Owens et al., Citation2015), the limited information about users, such as the lack of visual cues and their tone of voice, was a barrier to moderation. Restructuring the physical/social environment (BCT) offers potential intervention options. Lederman et al. (Citation2014) argue that the anonymity of the online environment can help young people open up and share more personal information than in face-to-face environments. Their promising study used principles of Social Accountability to create an environment of openness and trust in the design of an online mental health tool. Users and moderators were given multiple channels to share information (for example, detailed but anonymised personal profiles, personal messages and newsfeeds), improving moderators understanding of users and their ability to detect early warning signs of potential issues.

Access to timely support

Moderators reported that support was not always available “in the moment”. Given concerns about the safety and wellbeing of moderators working with vulnerable populations online, and the safety of the users themselves (Perry et al., Citation2021), timely support for moderators is crucial. “Restructuring the physical/social environment” (BCT) provides potential strategies for optimisation. For example, an on-call supervisor, as suggested in Webb et al. (Citation2008), could address this gap by providing moderators with immediate support, particularly for difficult or distressing posts. This would allow moderators the opportunity to debrief when it is most needed, with a potential positive spill-over to countering the barrier of emotional exhaustion.

Vagueness within the guidelines

Moderators recognised that upholding the forum’s guidelines was an important aspect of moderation. However, vagueness in the self-harm guidelines could be a barrier to knowing what action to take. To address this, the BCT “prompt/cue” is suggested. An intervention that has been developed for an Australian young people’s mental health forum could be considered here. Using machine learning technology, a “Moderator Assistant” system detects keywords in forum posts, flags these to moderators and suggests suitable responses which can be tailored and posted to the forum by moderators, making it easier and clearer for moderators to respond in different situations (Hussain et al., Citation2015).

Influence of the community users

Forum users could be both an enabler and a barrier to moderation. Users flagging posts of concern or offering support to other users were recognised as having a positive influence. At the same time, users could be a negative influence, challenging moderators’ actions and causing them to question their decision making or making them feel forced into “over-moderating”. Social support was selected as the most promising BCT. An example of this BCT is providing a “buddy”. Moderators could work in pairs with each other, providing mutual support in situations where users challenge or respond negatively to moderators. Such systems have been effective in changing and maintaining behaviour, albeit in different contexts (West et al., Citation1998).

Limitations

The convenience sampling strategy may have led to self-selection bias (Heckman, Citation1990) with the more confident moderators or those who moderate more self-harm content taking part, potentially affecting the barriers identified. Additionally, given the small total population size and to protect anonymity, no individual demographic data of the moderators are presented. However, the sample was found to be broadly representative of the organisation’s moderators. Nevertheless, the study involved a single online forum, so findings may not necessarily translate to other online forums in different contexts.

Conclusion

This study adds to the evidence base, showing that behaviour change frameworks can be effectively applied to the area of mental health and mental health interventions (Moran & Gutman, Citation2021). This study further addresses a major gap in the literature; revealing the challenges faced by moderators supporting a high-risk, vulnerable population, remotely and concerning an extremely sensitive subject. The strategies put forward focus on increasing the support and level of information available to moderators and could be considered by other organisations providing similar services. This may go some way to alleviating concerns about the wellbeing and safety of moderators, and the users they support (Perry et al., Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., Foy, R., Duncan, E. M., Colquhoun, H., Grimshaw, J. M., Lawton, R., & Michie, S. (2017). A guide to using the *Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burton, M. (2014). Self-harm: Working with vulnerable adolescents. Practice Nursing, 25(5), 245–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/pnur.2014.25.5.245

- Cane, J., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Ladha, R., & Michie, S. (2015). From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCT s) to structured hierarchies: Comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCT s. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 130–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12102

- Department of Health. (2017). *Preventing suicide in England: Third progress report of the cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives.

- Evans, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2005). In what ways are adolescents who engage in self-harm or experience thoughts of self-harm different in terms of help-seeking, communication and coping strategies? Journal of Adolescence, 28(4), 573–587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.11.001

- Hanley, T., Prescott, J., & Gomez, K. U. (2019). A systematic review exploring how young people use online forums for support around mental health issues. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 28(5), 566–576.

- Heckman, J. J. (1990). Selection bias and self-selection. *In Econometrics (pp. 201–224). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huh, J., Marmor, R., & Jiang, X. (2016). Lessons learned for online health community moderator roles: A mixed-methods study of moderators resigning from WebMD communities. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(9), e247.

- Human Behaviour Change Project. (2019). *The Theory and Technique Tool | Theory and Technique Tool. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/tool

- Hussain, M. S., Li, J., Ellis, L. A., Ospina-Pinillos, L., Davenport, T. A., Calvo, R. A., & Hickie, I. B. (2015). Moderator assistant: A natural language generation-based intervention to support mental health via social media. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 33(4), 304–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2015.1105768

- Jones, R., Sharkey, S., Ford, T., Emmens, T., Hewis, E., Smithson, J., Sheaves, B., & Owens, C. (2011). Online discussion forums for young people who self-harm: user views. The Psychiatrist, 35(10), 364–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.110.033449

- Kendal, S., Kirk, S., Elvey, R., Catchpole, R., & Pryjmachuk, S. (2017). How a moderated online discussion forum facilitates support for young people with eating disorders. Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 20(1), 98–111.

- Lederman, R., Wadley, G., Gleeson, J., Bendall, S., & Álvarez-Jiménez, M. (2014). Moderated online social therapy: Designing and evaluating technology for mental health. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 21(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2513179

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart, A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12(8), e0181722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181722

- McGowan, L. J., Powell, R., & French, D. P. (2020). How can use of the *Theoretical Domains Framework be optimized in qualitative research? A rapid systematic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(3), 677–694.

- McManus, S., Bebbington, P. E., Jenkins, R., & Brugha, T. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: The adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. NHS Digital.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel. A guide to designing interventions (1st ed., pp. 1003–1010). Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Michie, S., & West, R. (2013). Behaviour change theory and evidence: A presentation to Government. Health Psychology Review, 7(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.649445

- Montaner, X., Tárrega, S., Pulgarin, M., & Moix, J. (2021). Effectiveness of *Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in professional dementia caregivers burnout. Clinical Gerontologist, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1920530

- Moran, R., & Gutman, L. M. (2021). Mental health training to improve communication with children and adolescents: A process evaluation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(3–4), 415–432.

- Owens, C., Sharkey, S., Smithson, J., Hewis, E., Emmens, T., Ford, T., & Jones, R. (2015). Building an online community to promote communication and collaborative learning between health professionals and young people who self-harm: An exploratory study. Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 18(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12011

- Perry, A., Pyle, D., Lamont-Mills, A., du Plessis, C., & du Preez, J. (2021). Suicidal behaviours and moderator support in online health communities: A scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(6), e047905.

- Powell, D. (1996). A peer consultation model for clinical supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 14(2), 163–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v14n02_14

- Richiello, M. G., Mawdsley, G., & Gutman, L. M. (2022). Using the *Behaviour Change Wheel to identify barriers and enablers to the delivery of webchat counselling for young people. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 130–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12410

- Samaritans. (2020). *Managing self-harm and suicide content online. [online] Available at: <https://media.samaritans.org/documents/Online_Harms_guidelines_FINAL.pdf> [Accessed 16 December 2021].

- Smedley, R. M., & Coulson, N. S. (2017). A thematic analysis of messages posted by moderators within health-related asynchronous online support forums. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(9), 1688–1693.

- Smithson, J., Sharkey, S., Hewis, E., Jones, R., Emmens, T., Ford, T., & Owens, C. (2011). Problem presentation and responses on an online forum for young people who self-harm. Discourse Studies, 13(4), 487–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445611403356

- Webb, M., Burns, J., & Collin, P. (2008). Providing online support for young people with mental health difficulties: Challenges and opportunities explored. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 2(2), 108–113.

- West, R., Edwards, M., & Hajek, P. (1998). A randomized controlled trial of a "buddy" systems to improve success at giving up smoking in general practice. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 93(7), 1007–1011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93710075.x

- Whitlock, J. L., Powers, J. L., & Eckenrode, J. (2006). The virtual cutting edge: The internet and adolescent self-injury. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 407–417.

- Wise, K., Hamman, B., & Thorson, K. (2006). Moderation, response rate, and message interactivity: Features of online communities and their effects on intent to participate. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00313.x