Abstract

Background

During the decades representing working-age adulthood, most people will experience one or several significant life events or transitions. These may present a challenge to mental health.

Aim

The primary aim of this rapid systematic review of systematic reviews was to summarise available evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to promote and protect mental health relating to four key life events and transitions: pregnancy and early parenthood, bereavement, unemployment, and housing problems. This review was conducted to inform UK national policy on mental health support.

Methods

We searched key databases for systematic reviews of interventions for working-age adults (19 to 64 years old) who had experienced or were at risk of experiencing one of four key life events. Titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers in duplicate, as were full-text manuscripts of relevant records. We assessed the quality of included reviews and extracted data on the characteristics of each literature review. We prioritised high quality, recent systematic reviews for more detailed data extraction and synthesis.

Results

The search and screening of 3997 titles/abstracts and 239 full-text papers resulted in 134 relevant studies, 68 of which were included in a narrative synthesis. Evidence was strongest and of the highest quality for interventions to support women during pregnancy and after childbirth. For example, we found benefits of physical activity and psychological therapy for outcomes relating to mental health after birth. There was high quality evidence of positive effects of online bereavement interventions and psychological interventions on symptoms of grief, post-traumatic stress, and depression. Evidence was inconclusive and of lower quality for a range of other bereavement interventions, unemployment support interventions, and housing interventions.

Conclusions

Whilst evidence based mental health prevention and promotion is available during pregnancy and early parenthood and for bereavement, it is unclear how best to support adults experiencing job loss, unemployment, and housing problems.

Background

Working-age adulthood represents decades of a person’s life. In this period most people experience one or several significant life events or transitions. These typically cause upheaval and uncertainty and may present a challenge to mental health.

In a survey from the Mental Health Foundation among over 400 UK adults aged between 18 and 65, adults were asked to reflect on any life events which had affected them during adulthood. Life events reported to be most important for mental health included pregnancy and early parenthood, the death of a loved one, unemployment and job loss, and moving home and housing problems (Mental Health Foundation, Citation2021). This review aimed to assess evidence for mental health promotion and protection during and after these four key life events and transitions.

This review was conducted to inform a report on mental health during adulthood, with the aim to promote support for mental health challenges in adulthood in the UK (Mental Health Foundation, Citation2021).

Pregnancy and early parenthood

Pregnancy and early parenthood, including the numerous physical and emotional challenges they may bring, are experienced by millions of mothers and fathers every year. Whilst many new parents receive informal support from family and friends, others may lack support or require additional help. An estimated 12% of women experience perinatal depression during pregnancy or after the birth of their baby (Woody et al., Citation2017). New fathers can also experience perinatal depression and are less likely to receive a diagnosis and, therefore, formal support (Cameron et al., Citation2016). Formal support to help pregnant women and parents cope with the challenges they face ranges from community-based interventions such as group-based antenatal education for expectant parents through to psychological therapies.

Bereavement

For most people, grief is a natural and healthy response to the loss of a loved one. Complicated or prolonged grief is thought to affect daily life more severely and over a longer period (Shear et al., Citation2011). A Mental Health Foundation survey of UK adults found that 14% of people felt unsupported whilst experiencing a bereavement. In the same survey, adults on a lower income were more likely to feel unsupported (21%) (Mental Health Foundation, Citation2021). There are indications of variation in service provision of bereavement services in the UK (Wakefield et al., Citation2020). Interventions to help people cope with grief include psychological services, groups providing social support, and interventions with an element of psychoeducation (Johannsen et al., Citation2019).

Unemployment and job loss

Unemployment in the UK has risen during the COVID-19 pandemic. In July 2021, the number of employees on a payroll was still lower than before the pandemic according to the Office for National Statistics Labour Market Overview (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2021). Job loss and unemployment may cause financial worries, anxiety, or depressive symptoms and experiencing job loss has been linked to an increased risk of suicide (Blakely et al., Citation2003). Support may come in the form of psychological interventions aimed at improving mental health or those interventions focussed on increasing the chance of new employment, with potential benefits for mental health (vocational programmes, unemployment benefit policies).

Moving home and housing problems

Moving home (changing residence) might be voluntary, or it may be forced by relationship breakdown, financial difficulties, instability relating to short-term property rental, or eviction. In a survey of UK adults, people associated moving home with excitement (56%) as well as anxiety (46%) (Mental Health Foundation, Citation2021). Housing problems including eviction, poor housing conditions, overcrowding are known to be associated with poor mental health (Singh et al., Citation2019). Interventions that could improve mental health for people experiencing these types of life events may target individuals by, for example, focussing on people who are vulnerably housed or at risk of experiencing homelessness. Community-level interventions which may affect mental health include improving existing housing conditions and the provision of suitable and affordable homes.

Aim

This rapid review of systematic reviews was conducted to inform the Mental Health Foundation’s 2021 State of a Generation report. Our primary aim was to summarise the available evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to promote and protect mental health relating to four key life events and transitions in adulthood. Our secondary aim was to assess the inequalities that may impact access to and effectiveness of such interventions.

Methods

The rapid systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2010). The PRISMA checklist can be found in the Supplementary material. The protocol has been registered in the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews (CRD42020205884).

There is no widely agreed definition of a “rapid review” (Tricco et al., Citation2015). We have chosen a pragmatic approach tailored to the aims of this review, whilst adhering to the key principles and elements of a systematic review.

Literature searches

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 16 Sept 2020), Ovid PsycINFO (all years to 29 Sept 2020), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (issue 10 of 12, October 2020). In addition, we browsed reviews published by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth and the Cochrane Workgroups. We conducted backwards citation searches (checking reference lists of included reviews) and ran forward citation searches using Google Scholar, to identify any other potentially relevant reviews We deliberately chose not to search other review databases due to operational difficulties (complexity of the search strategies and interface limitations).

We structured the search around mental health (terms for common mental disorders) combined with terms for either of the four main life change events: unemployment; housing; bereavement; pregnancy. We used relevant keywords and subject headings appropriate to each resource and applied a systematic review filter (for search terms see supplementary material). As this was a rapid review, we limited the search to English language publications. The full search can be found in the supplementary material.

Eligibility criteria

Study design

Systematic reviews with quantitative or qualitative syntheses were eligible for inclusion. If it was unclear from screening titles and abstract whether a study was a systematic review, full-text manuscripts were obtained and assessed for mention of a “systematic review” or “meta-analysis”. Studies were excluded if one of the following systematic review aspects was missing: selection criteria, systematic search, synthesis of included studies, quality assessment of included studies.

Ongoing studies, study protocols, and abstracts and titles for which no full-text manuscript could be obtained within two weeks of starting data extraction were excluded.

Population

We included reviews of working age adults (19–64 years old). Reviews of studies of children and adults were eligible for inclusion if information for adults was presented separately.

The study population had to be at risk of, likely to experience, or have experienced, any of these four life events and transitions: pregnancy and early parenthood; bereavement; unemployment and job loss; or moving home and housing problems.

The review did not include child bereavement, in-work factors, or interventions for homelessness. More detail and explanation can be found in our pre-registered review protocol (PROSPERO record CRD42020205884).

Interventions

We included reviews evaluating any intervention aimed at mental health promotion or prevention of the development of mental health conditions. These interventions may have been universal or targeted at adults who were at risk of, likely to experience, or have experienced, any of the four life events and transitions. Treatment of diagnosed mental disorders and relapse prevention interventions were ineligible, although some participants may have experienced mental health conditions.

Reviews with any comparator or no comparator were eligible for inclusion.

Outcomes

To be included, reviews had to include information on outcomes relating to symptoms or diagnoses of a mental health condition, quality of life, or wellbeing. We accepted reviews reporting the use of any measurement tool, such as the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for anxiety symptoms or Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) for depression symptoms. Studies focussing on the physical component of wellbeing only were excluded.

Study selection

Deduplicated records were uploaded in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2016). Four reviewers screened titles and abstracts independently, with all records screened in duplicate. Conflicts were resolved through discussion between the four reviewers. Full text manuscripts were sought and screened in duplicate by the review team. We recorded reasons for exclusion at this stage.

Data extraction

Information and data, including review characteristics and number of included primary studies, were extracted in Microsoft Excel for all included studies.

To prevent duplication and ensure our review findings were as informative as possible, we selected “priority” reviews for a detailed narrative synthesis and quality assessment. Within each subgroup of reviews reporting on a similar population and intervention for one of the key life events and transitions, we gave preference to reviews which were conducted most recently. We also prioritised Cochrane reviews as these have been found to be of higher quality than non-Cochrane reviews (Moher et al., Citation2007). For prioritised reviews, we extracted data on review design and methodology, participant characteristics, number of included studies, interventions, and outcomes in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2016). One reviewer extracted the data, with 15% of studies checked by a second reviewer, and differences resolved through discussion.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted by one of the four reviewers and 15% of assessments were checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. We used the CASP checklist for systematic reviews to critically appraise the quality of included systematic reviews at the study level (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2019).

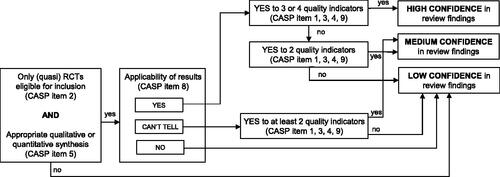

As this rapid review was conducted to inform a report for policy makers, patients, and the public in the UK, we developed a pragmatic method to convey our confidence in the findings from each included systematic review based on the CASP checklist (). These categories of low, medium, and high confidence in the results were based on the following criteria:

Did the inclusion criteria of the review specify that only (quasi) randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion (CASP item 2)?

Was an appropriate quantitative or qualitative synthesis was conducted (CASP item 5)?

Are results likely to be applicable to the UK population of working age adults (CASP item 8)?

Quality of the review (CASP items 1, 3, 4, 9).

The results of these assessments were used to inform our conclusions and implications for future research, for practice, and for patients and the public.

Synthesis

We narratively synthesised results for each key life event or transition. We categorised findings by type or intervention, population, and outcome and highlighted findings relating to inequalities that might impact access to and effectiveness of interventions within populations. We did not assess results from primary studies included in the systematic reviews.

Results

Study selection

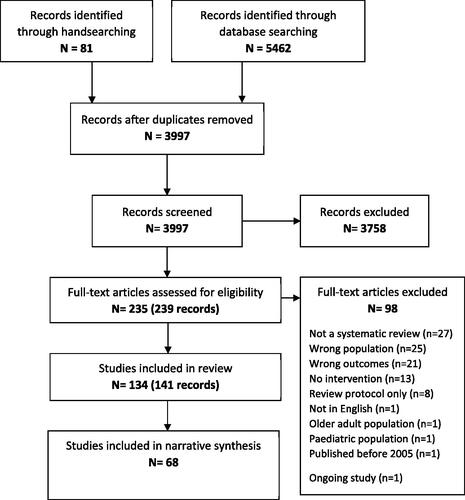

The MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases were searched between 16 and 29 September 2020 and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) was searched on 5 October 2020. Further handsearching of reviews published by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the Cochrane Work Group, together with backwards and forwards citation searching (performed in early October 2020) identified other relevant reviews.

After removing duplicates, 3997 records were screened (). The most common reasons for exclusion of full-text manuscripts were that the study was not a systematic review (n = 27), that the review did not focus on one of the four key life events or transitions (n = 25), or that no relevant outcomes were included (n = 21). A total of 134 systematic reviews was included and 69 of these were priority studies that we included in the narrative synthesis.

General description of all included reviews

We briefly summarise the characteristics of included systematic reviews here and categorise reviews within life events and transitions (k = number of reviews).

Pregnancy and early parenthood

Of the 134 included systematic reviews, 98 assessed interventions relating to pregnancy and early parenthood. Forty-seven reviews assessed interventions in pregnancy and after birth. Other reviews focussed on the pregnancy period (k = 23), interventions during labour (k = 5), or after birth (k = 23). Most reviews included a general population in any of these phases of pregnancy and childbirth, of mostly or exclusively women (k = 63), couples (k = 9), or fathers/partners (k = 5). Other reviews included only women considered to be at risk of developing mental health problems, for example because of a previous miscarriage or stillbirth (k = 6), previous or current pregnancy/birth complications (k = 5), or because they were experiencing social or socioeconomic disadvantage (Clarke et al., Citation2013) (Rojas-Garcia et al., Citation2014). Reviews commonly included a mix of interventions (k = 24). Others focussed on one type of intervention, such as physical activity or yoga (k = 11), psychological or arts-based therapy (k = 10), (psycho)education (k = 7), mindfulness and hypnosis (k = 5), dietary supplements (k = 4), or aromatherapy (k = 3).

Bereavement

Eighteen systematic reviews focussed on bereavement interventions. Seven reviews included a general population of people who experienced bereavement. Others focussed on loss of a loved one under specific circumstances. These included bereavement through suicide (k = 4), homicide (Alves-Costa et al., Citation2019), cancer (Gauthier & Gagliese, Citation2012), dementia (Wilson et al., Citation2017), sudden or unexpected death (Bartone et al., Citation2019), or advanced illness (Harrop, Morgan et al., Citation2020). One study reviewed evidence on interventions for mass bereavement (Harrop et al., Citation2020) and another focussed on interventions delivered in an intensive care unit (Efstathiou et al., Citation2019).

Unemployment

Of the twelve systematic reviews on unemployment, six reviews included a mix of interventions for a general population of unemployed people. Three reviews included return-to-work interventions for a mixed population (Franche et al., Citation2005), or for people who experienced cardiovascular disease (Hegewald et al., Citation2019) or cancer (de Boer et al., Citation2011). Two reviews assessed welfare-to-work interventions for lone parents (Campbell et al., Citation2016) (Gibson et al., Citation2017) and one review included a range of interventions aimed at young adults (Mawn et al., Citation2017).

Moving home

Six systematic reviews assessed evidence for (re)housing interventions. Even though not all six reviews were restricted to a specific population, they were all likely to include participants who were considered vulnerable, such as homeless and vulnerably housed people (Bassuk et al., Citation2014) (Ponka et al., Citation2020) or those living on a low income (Thomson et al., Citation2013). Reviews included a mix of housing interventions and all six reviews included rehousing interventions relevant to our review.

Narrative synthesis of prioritised reviews

Pregnancy and early parenthood

Of the 98 systematic reviews included for this life event and transition period, 43 were prioritised for further synthesis. In twenty-two reviews results were analysed using a narrative synthesis of results, meta-analyses were reported in 18 reviews and in two reviews a qualitative synthesis using thematic analysis was conducted. Seventeen reviews only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs.

Sixteen reviews focussed on the antenatal period (before birth) or childbirth itself. Three of these reviews explicitly included partners in the selection criteria. Seventeen reviews, fifteen of which were of women only, reviewed evidence on perinatal interventions, covering pregnancy, childbirth and up to a year after birth. There were nine reviews of postnatal interventions, three of which included partners. One review studied interventions for women who had experienced a miscarriage (Murphy et al., Citation2012).

Reviews included a mix of interventions (k = 15), or mind-body interventions such as mindfulness therapy, yoga, or creative approaches (k = 8), psychological therapy or psychoeducation (k = 8), interventions delivered in hospital or by midwives or health visitors (k = 7), or others (k = 5).

Bereavement

We included 18 systematic reviews on bereavement interventions and prioritised 12 for detailed synthesis. Three reviews included a meta-analysis of results (Johannsen et al., Citation2019) (Maass et al., Citation2020) (Wagner et al., Citation2020). Only RCTs were eligible for inclusion in these meta-analyses. One study used a rapid review design (Burrell & Selman, Citation2020), and the others were narratively synthesised.

Five reviews included interventions for adults who had experienced a bereavement (Bartone et al., Citation2019), (Burrell & Selman, Citation2020) (Johannsen et al., Citation2019) (Maass et al., Citation2020) (Wagner et al., Citation2020). The others focussed on specific populations, such as individuals bereaved by homicide (Alves-Costa et al., Citation2019) or suicide (Andriessen et al., Citation2019). All reviews included psychological interventions, with some focussing on specific formats or modes of delivery such as peer support (Bartone et al., Citation2019) or support groups (Maass et al., Citation2020).

Unemployment

Twelve systematic reviews were identified for this theme, of which eight were prioritised. Six reviews were meta-analyses including (quasi)RCTs only and two were systematic reviews with narrative syntheses (Audhoe et al., Citation2010)(Renahy et al., Citation2018).

Four reviews included unemployed adults (Audhoe et al., Citation2010) (Hult et al., Citation2020) (Moore et al., Citation2017) (Renahy et al., Citation2018) and one review included young adults not in education, employment, or training (Mawn et al., Citation2017). The other reviews focussed on specific groups of unemployed people such as lone parents (Gibson et al., Citation2017), people with chronic heart conditions (Hegewald et al., Citation2019), and adults with a cancer diagnosis (de Boer et al., Citation2011).

Moving home

For this theme, out of the six included systematic reviews, we prioritised one meta-analysis (Ponka et al., Citation2020) and four systematic reviews with narrative syntheses (Bassuk et al., Citation2014) (Gibson et al., Citation2011) (Ige et al., Citation2019) (Thomson et al., Citation2013).

Reviews focussed on the general population (Ige et al., Citation2019) (Gibson et al., Citation2011) (Thomson et al., Citation2013), or homeless and vulnerably housed people (Bassuk et al., Citation2014) (Ponka et al., Citation2020).

All five reviews assessed evidence for housing support, such as access to or relocation to affordable homes (Ige et al., Citation2019), rehousing with house improvements (Thomson et al., Citation2013), and rental assistance programmes for tenants (Gibson et al., Citation2011).

Quality assessment of prioritised reviews

Results of the quality assessment of included reviews is described narratively in the paragraphs below and presented in figures in the Supplementary material (Figures 3 and 4).

Pregnancy and early parenthood

Based on our quality assessment using the CASP checklist for systematic reviews (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2019) we had high confidence in the findings from 16 systematic reviews on pregnancy and early parenthood. These reviews generally asked a clearly specified research question and combined results in an appropriate way. We considered the results of these studies applicable to the UK situation and population. Quality issues were identified for a few of these reviews. Three reviews may not have included all relevant studies (Alderdice et al., Citation2013) (Brown et al., Citation2015) (Crane et al., Citation2020). Two reviews did not provide a comprehensive quality assessment of included studies (Dipietro et al., Citation2019) (Matvienko-Sikar et al., Citation2020).

For five reviews we have medium confidence in the findings, due to important limitations regarding the precision and applicability of the results (Bohren et al., Citation2017) (Dugas et al., Citation2012) (Jahanfar et al., Citation2014) (Lavender et al., Citation2013) (Shaw et al., Citation2006). Two reviews may not have included all relevant studies (Dugas et al., Citation2012) (Shaw et al., Citation2006).

We had low confidence in the findings of 22 included reviews. Eleven of these reviews did not look for the right type of papers, three did not include all relevant studies, and in five reviews the quality of included studies was not addressed. With one exception (Dol et al., Citation2020), effect estimates were imprecise due to wide confidence intervals or not clearly reported. Three reviews did not report all outcomes relevant to the research question (D'Haenens et al., Citation2020) (Hong et al., Citation2020) (O’Connell et al., Citation2020).

Bereavement

We had high confidence in the findings of five reviews (Andriessen et al., Citation2019) (Andriessen et al., Citation2019a) (Harrop et al., Citation2020) (Johannsen et al., Citation2019) (Wagner et al., Citation2020) (Figure 4). The other seven reviews were rated as “low confidence” for one or more of the following reasons: authors did not look for the right type of papers, responses were not combined in a valid way, and results could not be applied to the UK situation and population.

Unemployment

For the reviews on unemployment, we had high confidence in the findings from two systematic reviews (de Boer et al., Citation2011) (Hult et al., Citation2020). We were unsure about applicability to the UK situation and population for two reviews, which were consequently rated as “medium confidence” (Gibson et al., Citation2017) (Moore et al., Citation2017). For four reviews we had low confidence in the findings because of limitations regarding the search strategy (Audhoe et al., Citation2010) (Renahy et al., Citation2018) or poor generalisability of the results (Hegewald et al., Citation2019) (Mawn et al., Citation2017).

Moving home

We had medium confidence in the findings of two systematic reviews (Ige et al., Citation2019) (Ponka et al., Citation2020) and low confidence in the findings of three systematic reviews (Bassuk et al., Citation2014) (Gibson et al., Citation2011) (Thomson et al., Citation2013). The evidence was limited by a lack of precision in the results and missing outcomes (Gibson et al., Citation2011) (Thomson et al., Citation2013). None of the results from the included reviews would be easily applied to the UK population.

Effectiveness of mental health promotion and prevention interventions

Pregnancy and early parenthood

Forty-three prioritised reviews were included in this theme ().

Table 1. Summary of evidence for effectiveness of pregnancy and early parenthood interventions.

There was some evidence for the positive effect of mind-body interventions on mental health. Art therapy reduced childbirth fear (Crane et al., Citation2020), a music intervention reduced anxiety during labour (Chuang et al., Citation2019), physical activity reduced symptoms of postnatal depression (Dipietro et al., Citation2019), and symptoms of both depression and anxiety were improved by yoga practice in the perinatal phase (Sheffield & Woods-Giscombe, Citation2016). Aromatherapy delivered postnatally reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety (Rezaie-Keikhaie et al., Citation2019), but no effect on anxiety symptoms was found during labour (Liao et al., Citation2020). There was no clear evidence of benefit for omega-3 supplementation to prevent postnatal depression (Middleton et al., Citation2018) and not enough evidence was available on the effects of physical activity on postnatal anxiety (Dipietro et al., Citation2019).

Of the seven reviews of interventions delivered by healthcare professionals (midwives, obstetricians, health visitors), reviews reported positive effects of elective c-section on symptoms of anxiety and depression (Olieman et al., Citation2017), continuous one-to-one support during labour on symptoms of perinatal depression (Bohren et al., Citation2017), and decision aids on anxiety symptoms (Dugas et al., Citation2012). There was no evidence of positive mental health effects of women carrying their own case notes (Brown et al., Citation2015), specialised antenatal care (Dodd & Crowther, Citation2012), and continuity of care (D'Haenens et al., Citation2020). Extended postnatal care reduced symptoms of depression, but postnatal care at home rather than in hospital had no effect on anxiety or depression symptoms (Yonemoto et al., Citation2013).

There was no strong evidence of positive effects of psychoeducation on levels of stress, postnatal depression, and postnatal anxiety (Brixval et al., Citation2015) (Dol et al., Citation2020) (Hong et al., Citation2020).

Reviews of psychological therapies found no clear effects of debriefing (Bastos et al., Citation2015) and psychological support after miscarriage (Murphy et al., Citation2012), mixed findings for heart rate variability feedback depending on the type of mental health diagnosis (Herbell & Zauszniewski, Citation2019), and potential beneficial effects of antenatal counselling for parents who received a diagnosis of a foetal congenital anomaly (Marokakis et al., Citation2016).

When considering only evidence which received a “high confidence” rating, evidence of positive effects on prevention or symptom reduction of postnatal depression was strongest for art therapy for childbirth fear (Crane et al., Citation2020), physical activity (Dipietro et al., Citation2019), and psychological therapy (Dennis & Dowswell, Citation2013).

Bereavement

Reductions in symptoms of post-traumatic stress, grief and depression were found for online bereavement interventions (Wagner et al., Citation2020) and psychological interventions (Johanssen et al., Citation2019) (). There was some evidence of a positive effect of peer support on depression symptoms (Bartone et al., Citation2019) and some positive effects on mental health for support after suicide (Andriessen et al., Citation2019), psychosocial interventions for grief relating to dementia (Wilson et al., Citation2017), and support for people bereaved through advanced illness (Harrop et al., Citation2020).

Table 2. Summary of evidence for effectiveness of bereavement interventions.

Evidence was inconclusive for the effects of the following interventions on mental health symptoms and wellbeing: funeral practices (Burrell & Selman, Citation2020), psychological support after homicide (Alves-Costa et al., Citation2019), support services after mass bereavement (Harrop et al., Citation2020), support after bereavement following a stay on the Intensive Care Unit (Efstathiou et al., Citation2019), and bereavement support groups (Maass et al., Citation2020).

When considering results from high quality studies in which we have a high level of confidence, evidence of positive effects on grief, symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression was strongest for online bereavement interventions (Wagner et al., Citation2020) and psychological interventions (Johanssen et al., Citation2019).

Unemployment

There was no strong evidence of positive effects on any mental health outcomes for employment support (Gibson et al., Citation2017, Hegewald et al., Citation2019, Mawn et al., Citation2017) or psychological interventions (de Boer et al., Citation2011) (Moore et al., Citation2017) (see Table 3, Supplementary Information). In one review, two out of five studies of group vocational training found that the intervention lowered psychological distress in the short term (Audhoe et al., Citation2010). Mixed findings, generally based on lower quality studies, were reported for unemployment insurance (Renahy et al., Citation2018).

One high quality systematic review found no studies on interventions to promote return-to-work for cancer patients (de Boer et al., Citation2011). The other high-quality review found no evidence of effects of therapeutic interventions on mental health outcomes of unemployed job seekers (Hult et al., Citation2020).

Moving home

Authors of these reviews generally concluded that more research is needed to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of interventions (Ige et al., Citation2019). High quality evidence was sparse (Ige et al., Citation2019) and results were mostly inconsistent (Bassuk et al., Citation2014) (Ponka et al., Citation2020) (Thomson et al., Citation2013) see (Table 4, Supplementary Information).

There was some evidence to suggest that interventions aimed at improving housing conditions, either by moving people or providing rental assistance, can lead to better mental health (Gibson et al., Citation2011). However, we do not have high confidence in the findings of these systematic reviews due to quality concerns.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Systematic reviews of studies on pregnancy and early parenthood suggested potential benefits of several interventions delivered in pregnancy, during childbirth, and after childbirth. Evidence was strongest and of the highest quality for the beneficial effects of art therapy on childbirth fear, and for physical activity and psychological therapy on postnatal depression outcomes.

There was high quality evidence of positive effects of online bereavement interventions and psychological interventions on symptoms of grief, post-traumatic stress, and depression. Evidence was inconclusive and of lower quality for a range of interventions including bereavement support groups and specialised support for specific groups such as those bereaved after a homicide or after a stay on an Intensive Care Unit.

Evidence for employment support interventions was mixed, with reviews reporting positive effects as well as a lack of effect on mental health. Findings were limited by a lack of primary studies and limited geographical representation.

There was some lower quality evidence to suggest that interventions aimed at improving housing conditions could lead to better mental health.

We found no reviews systematically assessing access to or effectiveness of interventions for different population groups. We were therefore not able to draw any conclusions regarding our secondary aim, to assess the inequalities that may impact access to and effectiveness of interventions.

Generalisability of the evidence

This rapid review of systematic reviews was conducted to inform a report on mental health support for working age adults in the UK (Mental Health Foundation, Citation2021). Not all evidence from the included systematic reviews is easily applicable to the UK situation. Even among high income countries, the level of support available to adults experiencing a key life event or transition differs, and this may affect the effectiveness of interventions. For example, women in the UK have access to comprehensive midwifery care and healthcare during pregnancy and beyond and financial support is provided to women in the form of paid maternity leave or maternity allowance. These services are likely to promote and protect mental health, and any additional interventions for the general, low risk population may appear less effective as a result (Van Niel et al., Citation2020). Most evidence on housing interventions was from older studies conducted in countries other than the UK, where the relationship between housing and mental health may be different from other countries. For example, receiving support to move from a poorer to a more affluent neighbourhood, such as in the US based “Moving to Opportunity” intervention, may benefit mental health most in countries or local areas with the starkest differences in area deprivation (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Citation2003).

In this rapid systematic review, and the systematic reviews we included, evidence is neatly categorised according to four key life events and transitions. In reality, life events may occur simultaneously or influence each other to exacerbate any impact on mental health, and this is more likely to be the case for socially disadvantaged groups of the population. For example, homelessness is linked to poverty, unemployment, and local labour market conditions (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018). This review did not consider evidence of more holistic interventions which address the social disadvantage burdening people who struggle to cope with life events and transitions in adulthood. A panel of mental health professionals previously suggested the future of professional mental health support may include interventions aiming to modify the social context of people who are experiencing psychological distress, rather than focussing on symptoms (Giacco et al., Citation2017).

Limitations

The intention of this rapid review of systematic reviews was to provide a high-level assessment of the available evidence. The methods used provide for an overview only and do not allow for direct inclusion and summary of primary studies. It is likely that not all primary studies on the four life events and transition periods of adulthood will have been included in the reviews identified. This may be due to differences in the review questions being addressed, the inclusion criteria and search strategies used, and the year the review was conducted. Although recent primary studies are likely to be missing from these reviews, we did prioritise recently published systematic reviews in our overview.

A possible limitation of our approach is that, in some cases, the primary studies might have appeared in more than one review summarised here. We mitigated this risk by prioritising more recent reviews and Cochrane reviews if multiple reviews covering the same population and interventions were identified.

We used a pragmatic rapid review approach to identify and summarise the findings of systematic reviews in a short timeframe. Although we adhered to the general principles of a systematic review, in line with rapid review methodology, we limited the number of databases searched and focused our more detailed assessment of the evidence on a subset of reviews. It is therefore possible that important systematic reviews may have been missed. Prioritising Cochrane reviews could have led to a skewed overview of the evidence, favouring established research groups supported and resourced to undertake more extensive high-quality reviews.

Our focus on implications of the evidence for the UK might limit the generalisability of the findings of this review for other settings. For example, we assessed “relevance for the UK setting” as part of the critical appraisal of the evidence.

Implications for research and practice

Evidence for effective mental health support

This review of systematic reviews provides an overview of evidence currently available to inform decisions on the provision of mental health support during key life events and transitions in adulthood.

It is likely that implementation of physical activity interventions in the community and access to psychological therapy and postnatal community midwifery support can promote the mental health of mothers after childbirth. Online bereavement interventions and psychological interventions are likely to improve symptoms of grief, post-traumatic stress, and depression for people who are coping with a bereavement. These interventions may be considered for evaluation and implementation in UK settings.

Evidence of no effect and lack of evidence

We found much more, more recent and better-quality evidence on the effectiveness of interventions relating to pregnancy and early parenthood, than we did for the other three life events and transitions. Even so, most of the evidence for pregnancy and early adulthood interventions focussed on preventing postnatal depression, rather than general wellbeing or anxiety. Partners or fathers were rarely offered support as part of these interventions.

For a host of other interventions, the evidence is inconclusive and, at times, contradictory. Rigorous evaluations and systematic reviews are needed on early parenthood interventions supporting partners, bereavement support groups, and interventions aimed at improving housing conditions and supporting people with housing problems. Employment support interventions included in this review were primarily aimed at facilitating return-to-work or achieving employment, and it was unclear whether these interventions can simultaneously promote mental health. Interventions specifically aimed at protecting the mental health of those who experience job loss or unemployment is needed.

Inequalities in mental health support

Systematic reviews considered evidence for the general population (for example, bereaved adults) or specific groups within a population (for example, women at risk of postnatal depression). There was little consideration of inequalities in the effectiveness of interventions for these key life events and transitions. This is concerning because primary studies show inequalities in access to and effectiveness of such interventions. For example, common mental disorders during and after pregnancy are less likely to be recognised and treated among minority ethnic women in the UK (Prady et al., Citation2021). A range of factors including culturally insensitive service providers may impact access to perinatal care (Watson et al., Citation2019). Future systematic reviews and primary studies may wish to assess the effectiveness of interventions for different groups of the population, and particularly those with greater mental health needs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (77.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Data availability statement

Data and information extracted from the included systematic reviews are available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aitken, Z., Garrett, C.C. & Hewitt, B. (2015) The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 130, 32–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.001

- Alderdice, F., McNeill, J., & Lynn, F. (2013). A systematic review of systematic reviews of interventions to improve maternal mental health and well-being. Midwifery, 29(4), 389–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.05.010

- Alves-Costa, F., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Christie, H., van Denderen, M., & Halligan, S. (2019). Psychological interventions for individuals bereaved by homicide: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 22(4):793-803. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019881716

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Kõlves, K., & Reavley, N. (2019). Suicide postvention service models and guidelines 2014–2019: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2677. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02677.

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Hill, N., Reifels, L., Robinson, J., Reavley, N., & Pirkis, J. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: A systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2020-z.

- Audhoe, S. S., Hoving, J. L., Sluiter, J. K., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. (2010). Vocational interventions for unemployed: effects on work participation and mental distress. A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9223-y.

- Bartone, P. T., Bartone, J. V., Violanti, J. M., & Gileno, Z. M. (2019). Peer support services for bereaved survivors: A systematic review. Omega, 80(1), 137–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817728204

- Bassuk, E. L., DeCandia, C. J., Tsertsvadze, A., & Richard, M. K. (2014). The effectiveness of housing interventions and housing and service interventions on ending family homelessness: A systematic review. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(5), 457–474. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000020

- Bastos, M. H., Furuta, M., Smal, l R., McKenzie‐McHarg, K., & Bick, D, Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (2015). Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD007194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007194.pub2

- Blakely, T. A., Collings, S. C., & Atkinson, J. (2003). Unemployment and suicide. Evidence for a causal association? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(8), 594–600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.8.594.

- Boath, E., Bradley, E. & Henshaw, C. (2005). The prevention of postnatal depression: A narrative systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 26(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820400028431

- Bohren, M. A., Hofmeyr, G., Sakala, C., Fukuzawa, R. K., & Cuthbert, A. (2017). Continuous support for women during childbirth. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD003766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6

- Bramley, G., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Homelessnes in the UK: Who is most at risk? Housing Studies, 33(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344957

- Brixval, C. S., Axelsen, S. F., Lauemøller, S. G., Andersen, S. K., Due, P., & Koushede, V. (2015). The effect of antenatal education in small classes on obstetric and psycho-social outcomes - a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 4, 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0010-x.

- Brown, H. C., Smith, H. J., Mori, R., & Noma, H, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (2015). Giving women their own case notes to carry during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD002856. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002856.pub3

- Brown, J., Alwan, N. A., West, J., Brown, S., McKinlay, C. J., Farrar, D., & Crowther, C. A. (2017). Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD011970. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011970.pub2.

- Burrell, A., & Selman, L. E. (2020). How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives’ mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 003022282094129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820941296.

- Cameron, E. E., Sedov, I. D., & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. (2016). Prevalence of paternal depression in pregnancy and the postpartum: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 189–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.044.

- Campbell, M., Thomson, H., Fenton, C., & Gibson, M. (2016). Lone parents, health, wellbeing and welfare to work: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health, 16, 188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2880-9.

- Catling, C. J., Medley, N., Foureur, M., Ryan, C., Leap, N., Teate, A., & Homer, C. S. E, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. (2015). Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(1), CD007622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007622.pub3.

- Chuang, C. H., Chen, P. C., Lee, C. S., Chen, C. H., Tu, Y. K., & Wu, S. C. (2019). Music intervention for pain and anxiety management of the primiparous women during labour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(4), 723–733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13871.

- Clarke, K., King, M., & Prost, A. (2013). Psychosocial interventions for perinatal common mental disorders delivered by providers who are not mental health specialists in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 10(10), e1001541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001541.

- Crane, T., Buultjens, M., & Fenner, P. (2020). Art-based interventions during pregnancy to support women’s wellbeing: An integrative review. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(4), 325-334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.08.009

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP systematic review checklist. CASP. Retrieved 16 October 2020 from casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- D'Haenens, F., Van Rompaey, B., Swinnen, E., Dilles, T., & Beeckman, K. (2020). The effects of continuity of care on the health of mother and child in the postnatal period: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 30(4), 749–760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz082/

- de Boer, A. G., Taskila, T., Tamminga, S. J., Frings-Dresen, M. H., Feuerstein, M., & Verbeek, J. H. (2011). Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD007569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub2

- de Graaff, L. F., Honig, A., van Pampus, M. G., & Stramrood, C. A. I. (2018). Preventing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth and traumatic birth experiences: A systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 97(6), 648–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13291.

- Dennis, C. L., & Dowswell, T, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. (2013). Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD001134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001134.pub3.

- Dipietro, L., Evenson, K. R., Bloodgood, B., Sprow, K., Troiano, R. P., Piercy, K. L., Vaux-Bjerke, A., & Powell, K. E, Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2019). Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum: An umbrella review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(6), 1292–1302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941.

- Dodd, J. M., & Crowther, C. A. (2012). Specialised antenatal clinics for women with a multiple pregnancy for improving maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8), CD005300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005300.pub3

- Dol, J., Richardson, B., Murphy, G. T., Aston, M., McMillan, D., & Campbell-Yeo, M. (2020). Impact of mobile health interventions during the perinatal period on maternal psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 18(1), 30–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00191.

- Dugas, M., Shorten, A., Dube, E., Wassef, M., Bujold, E., & Chaillet, N. (2012). Decision aid tools to support women's decision making in pregnancy and birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(12), 1968–1978. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.041.

- Efstathiou, N., Walker, W., Metcalfe, A., & Vanderspank-Wright, B. (2019). The state of bereavement support in adult intensive care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Journal of Critical Care, 50, 177–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.026.

- Franche, R.-L., Cullen, K., Clarke, J., Irvin, E., Sinclair, S., & Frank, J, Institute for Work & Health (IWH) Workplace-Based RTW Intervention Literature Review Research Team (2005). Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 15(4), 607–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-005-8038-8.

- Gauthier, L. R., & Gagliese, L. (2012). Bereavement interventions, end-of-life cancer care, and spousal well-being: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 19(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2012.01275.x.

- Giacco, D., Amering, M., Bird, V., Craig, T., Ducci, G., Gallinat, J., Gillard, S. G., Greacen, T., Hadridge, P., Johnson, S., Jovanovic, N., Laugharne, R., Morgan, C., Muijen, M., Schomerus, G., Zinkler, M., Wessely, S., & Priebe, S. (2017). Scenarios for the future of mental health care: A social perspective. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(3), 257–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30219.

- Gibson, M., Petticrew, M., Bambra, C., Sowden, A. J., Wright, K. E., & Whitehead, M. (2011). Housing and health inequalities: A synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place, 17(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.011

- Gibson, M., Thomson, H., Banas, K., Lutje, V., McKee, M. J., Martin, S. P., Fenton, C., Bambra, C., & Bond, L. (2017). Welfare-to-work interventions and their effects on the mental and physical health of lone parents and their children. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD009820. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009820.pub2.

- Goldstein, Z., Rosen, B., Howlett, A., Anderson, M., & Herman, D. (2020). Interventions for paternal perinatal depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 505–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.12.029.

- Harrop, E., Mann, M., Semedo, L., Chao, D., Selman, L. E., & Byrne, A. (2020). What elements of a systems' approach to bereavement are most effective in times of mass bereavement? A narrative systematic review with lessons for COVID-19. Palliative Medicine, 34(9), 1165–1181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320946273.

- Harrop, E., Morgan, F., Longo, M., Semedo, L., Fitzgibbon, J., Pickett, S., Scott, H., Seddon, K., Sivell, S., Nelson, A., & Byrne, A. (2020). The impacts and effectiveness of support for people bereaved through advanced illness: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Palliative Medicine, 34(7), 871–888. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320920533.

- Hegewald, J., Wegewitz, U. E., Euler, U., van Dijk, J. L., Adams, J., Fishta, A., Heinrich, P., & Seidler, A. (2019). Interventions to support return to work for people with coronary heart disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD010748. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010748.pub2.

- Hennegan, J. M., Henderson, J., & Redshaw, M. (2015). Contact with the baby following stillbirth and parental mental health and well-being: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 5(11), e008616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008616

- Herbell, K., & Zauszniewski, J. A. (2019). Reducing psychological stress in peripartum women with heart rate variability biofeedback: A systematic review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 37(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010118783030.

- Hong, K., Hwang, H., Han, H., Chae, J., Choi, J., Jeong, Y., Lee, J., & Lee, K. J. (2020). Perspectives on antenatal education associated with pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(3), 219-230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.002

- Hult, M., Lappalainen, K., Saaranen, T. K., Rasanen, K., Vanroelen, C., & Burdorf, A. (2020). Health-improving interventions for obtaining employment in unemployed job seekers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD013152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013152.pub2.

- Ige, J., Pilkington, P., Orme, J., Williams, B., Prestwood, E., Black, D., Carmichael, L., & Scally, G. (2019). The relationship between buildings and health: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health, 41(2), e121–e132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy138.

- Jahanfar, S., Howard, L. M., & Medley, N. (2014). Interventions for preventing or reducing domestic violence against pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (11), CD009414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009414.pub3

- Johannsen, M., Damholdt, M. F., Zachariae, R., Lundorff, M., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O'Connor, M. (2019). Psychological interventions for grief in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 69–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.065.

- Jones, H. C., McKenzie-McHarg, K., & Horsch, A. (2015). Standard care practices and psychosocial interventions aimed at reducing parental distress following stillbirth: A systematic narrative review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(5), 448–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2015.1035234.

- Kingdon, C., Givens, J. L., O'Donnell, E., & Turner, M. (2015). Seeing and holding baby: Systematic review of clinical management and parental outcomes after stillbirth. Birth, 42(3), 206–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12176.

- Lavender, T., Richens, Y., Milan, S. J., Smyth, R. M., & Dowswell, T. (2013). Telephone support for women during pregnancy and the first six weeks postpartum. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD009338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009338.pub2

- Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1576–1582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576.

- Liao, C. C., Lan, S. H., Yen, Y. Y., Hsieh, Y. P., & Lan, S. J. (2020). Aromatherapy intervention on anxiety and pain during first stage labour in nulliparous women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 41(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1673707.

- Lin, P. Z., Xue, J. M., Yang, B., Li, M., & Cao, F. L. (2018). Effectiveness of self-help psychological interventions for treating and preventing postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 21(5), 491–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0835-0.

- Maass, U., Hofmann, L., Perlinger, J., & Wagner, B. (2020). Effects of bereavement groups-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Death Studies, 46(3), 708-718. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1772410

- Madden, K., Middleton, P., Cyna, A. M., Matthewson, M., & Jones, L. (2016). Hypnosis for pain management during labour and childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5), CD009356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009356.pub3

- Mahmalat, N., Ostermann, T., & Fetz, K. (2020). Preventive factors of postpartum depression in adult mothers: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Research Square, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-36611/v1.

- Marc, I., Toureche, N., Ernst, E., Hodnett, E. D., Blanchet, C., Dodin, S., & Njoya, M. M. (2011). Mind-body interventions during pregnancy for preventing or treating women’s anxiety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD007559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007559.pub2

- Marokakis, S., Kasparian, N. A., & Kennedy, S. E. (2016). Prenatal counselling for congenital anomalies: A systematic review. Prenatal Diagnosis, 36(7), 662–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4836.

- Matvienko-Sikar, K., Flannery, C., Redsell, S., Hayes, C., Kearney, P. M., & Huizink, A. (2020). Effects of interventions for women and their partners to reduce or prevent stress and anxiety: A systematic review. Women and Birth, 34(2), e97-e117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.02.010

- Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C., & Stain, H. J. (2017). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2.

- Mental Health Foundation. (2021). Upheaval, uncertainty, and change: themes of adulthood. A study of four life transitions and their impact on our mental health. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/MHF_S0G_REPORT_2021_UK_0.pdf.

- Middleton, P., Gomersall, J. C., Gould, J. F., Shepherd, E., Olsen, S. F., & Makrides, M. (2018). Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD003402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3

- Miller, B. J., Murray, L., Beckmann, M. M., Kent, T., & Macfarlane, B, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (2013). Dietary supplements for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD009104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009104.pub2.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P, PRISMA Group (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 8(5), 336–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007.

- Moher, D., Tetzlaff, J., Tricco, A. C., Sampson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2007). Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine, 4(3), e78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078.

- Moore, T. H., Kapur, N., Hawton, K., Richards, A., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2017). Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 1062–1084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002944.

- Morrell, C. J., Sutcliffe, P., Booth, A., Stevens, J., Scope, A., Stevenson, M., Harvey, R., Bessey, A., Cantrell, A., Dennis, C. L., Ren, S., Ragonesi, M., Barkham, M., Churchill, D., Henshaw, C., Newstead, J., Slade, P., Spiby, H., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2016). A systematic review, evidence synthesis and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions to prevent postnatal depression. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 20(37), 1–414.

- Murphy, F. A., Lipp, A., & Powles, D. L. (2012). Follow-up for improving psychological wellbeing for women after a miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), CD008679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008679.pub2

- O’Connell, M. A., Khashan, A. S., & Leahy-Warren, P. (2020). Women’s experiences of interventions for fear of childbirth in the perinatal period: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research evidence. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(3), e309-e321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.05.008

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2021). Labour market overview. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved October 4, 2021, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/july2021.

- Olieman, R. M., Siemonsma, F., Bartens, M. A., Garthus-Niegel, S., Scheele, F., & Honig, A. (2017). The effect of an elective cesarean section on maternal request on peripartum anxiety and depression in women with childbirth fear: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1371-z.

- Owais, S., Chow, C. H. T., Furtado, M., Frey, B. N., & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2018). Non-pharmacological interventions for improving postpartum maternal sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 41, 87–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2018.01.005.

- Philpott, L. F., Savage, E., FitzGerald, S., & Leahy-Warren, P. (2019). Anxiety in fathers in the perinatal period: A systematic review. Midwifery, 76, 54–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.05.013.

- Ponka, D., Agbata, E., Kendall, C., Stergiopoulos, V., Mendonca, O., Magwood, O., Saad, A., Larson, B., Sun, A. H., Arya, N., Hannigan, T., Thavorn, K., Andermann, A., Tugwell, P., & Pottie, K. (2020). The effectiveness of case management interventions for the homeless, vulnerably housed and persons with lived experience: A systematic review. PLOS One, 15(4), e0230896. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230896.

- Prady, S. L., Endacott, C., Dickerson, J., Bywater, T. J., & Blower, S. L. (2021). Inequalities in the identification and management of common mental disorders in the perinatal period: An equity focused re-analysis of a systematic review. PLOS One, 16(3), e0248631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248631.

- Renahy, E., Mitchell, C., Molnar, A., Muntaner, C., Ng, E., Ali, F., & O'Campo, P. (2018). Connections between unemployment insurance, poverty and health: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 28(2), 269–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx235.

- Rezaie-Keikhaie, K., Hastings-Tolsma, M., Bouya, S., Shad, F. S., Sari, M., Shoorvazi, M., Barani, Z. Y., & Balouchi, A. (2019). Effect of aromatherapy on post-partum complications: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 35, 290–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.03.010.

- Rojas-Garcia, A., Ruiz-Perez, I., Goncalves, D. C., Rodriguez-Barranco, M., & Ricci-Cabello, I. (2014). Healthcare interventions for perinatal depression in socially disadvantaged women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 363–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12081.

- Scime, N. V., Gavarkovs, A. G., & Chaput, K. H. (2019). The effect of skin-to-skin care on postpartum depression among mothers of preterm or low birthweight infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 376–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.101.

- Shaw, E., Levitt, C., Wong, S., & Kaczorowski, J, McMaster University Postpartum Research, G. (2006). Systematic review of the literature on postpartum care: effectiveness of postpartum support to improve maternal parenting, mental health, quality of life, and physical health. Birth, 33(3), 210–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00106.x

- Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., Reynolds, C., Lebowitz, B., Sung, S., Ghesquiere, A., Gorscak, B., Clayton, P., Ito, M., Nakajima, S., Konishi, T., Melhem, N., Meert, K., Schiff, M., O'Connor, M.-F., … Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20780.

- Sheffield, K. M., & Woods-Giscombe, C. L. (2016). Efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of perinatal yoga on women’s mental health and well-being: A systematic literature review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 34(1), 64–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010115577976.

- Singh, A., Daniel, L., Baker, E., & Bentley, R. (2019). Housing disadvantage and poor mental health: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(2), 262–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.018.

- Thomson, H., Thomas, S., Sellstrom, E., & Petticrew, M. (2013). Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD008657. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008657.pub2

- Tricco, A. C., Antony, J., Zarin, W., Strifler, L., Ghassemi, M., Ivory, J., Perrier, L., Hutton, B., Moher, D., & Straus, S. E. (2015). A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6

- Van Niel, M. S., Bhatia, R., Riano, N. S., de Faria, L., Catapano-Friedman, L., Ravven, S., Weissman, B., Nzodom, C., Alexander, A., Budde, K., & Mangurian, C. (2020). The impact of paid maternity leave on the mental and physical health of mothers and children: A review of the literature and policy implications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000246.

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2016). Covidence. [Computer Software]. Cochrane systematic review software.

- Wagner, B., Rosenberg, N., Hofmann, L., & Maass, U. (2020). Web-based bereavement care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00525.

- Wakefield, D., Fleming, E., Howorth, K., Waterfield, K., Kavanagh, E., Billett, H. C., Kiltie, R., Robinson, L., Rowley, G., Brown, J., Woods, E., & Dewhurst, F. (2020). Inequalities in awareness and availability of bereavement services in North-East England. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, bmjspcare-2020-002422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002422.

- Watson, H., Harrop, D., Walton, E., Young, A., & Soltani, H. (2019). A systematic review of ethnic minority women's experiences of perinatal mental health conditions and services in Europe. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210587.

- Wilson, S., Toye, C., Aoun, S., Slatyer, S., Moyle, W., & Beattie, E. (2017). Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in reducing grief experienced by family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(3), 809–839. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003017.

- Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A., & Harris, M. G. (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003.

- Yonemoto, N., Dowswell, T., Nagai, S., & Mori, R. (2013). Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum period. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7). CD009326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009326.pub2