As shown by several papers published in the Journal of Mental Health and elsewhere, reducing social isolation and increasing social connectedness have been identified as recovery priorities by service users with psychosis (Douglas et al., Citation2022; Wood & Alsawy, Citation2018) and with severe mental health difficulties in general (Cogan et al., Citation2021; Salehi et al., Citation2019). Service users emphasise the negative effects of social isolation in precluding community participation (Salehi et al., Citation2019; Tee et al., Citation2020) and “citizenship” (Cogan et al., Citation2021). Adding to this, recently there have been the distressing effects of physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Simblett et al., Citation2021).

From the epidemiological perspective, social isolation is a risk factor for adverse physical health outcomes, including early mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015; Pantell et al., Citation2013) and there is emerging evidence that it can induce or worsen psychotic experiences (Lamster et al., Citation2017; van Der Werf et al., Citation2010).

All this evidence clearly points towards social isolation as a prominent problem for people with psychosis.

Several efforts have been made to develop and test interventions to reduce social isolation in psychosis, with promising results. However, in this editorial it will be argued that these efforts and the scientific advances in this area need to consider the complexity of the concept of social isolation. Different studies have used a variety of constructs as outcomes to capture intervention effects. Examples are loneliness, social contacts, social capital, social networks, group membership, perceived social support.

All these concepts have important differences and they should not be, reductionistically, lumped together. Their differences make the effects of different interventions and the results of different observational studies difficult to compare.

Types of interventions which aim to improve social isolation outcomes will be briefly described. This will be followed by the presentation of a framework, which can be useful to understand and link the complex effects of interventions on the wide range of constructs within the social isolation “umbrella”. Finally the new opportunities and challenges for this type of interventions, which are brought about by societal changes and new technologies, will be discussed.

Helping people with psychosis to reduce social isolation: how?

Unfortunately, interventions which focus purely on symptoms, such as pharmacological treatment or symptom-focused psychological treatments have had a rather limited effect on social isolation (Barnes et al., Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2021).

Interventions which have instead focused on training people with psychosis towards social skills, and have been shown to be effective in improve theoretical social skills but to have a much attenuated effect on social outcomes (Turner et al., Citation2018).

A third and arguably more recently studied group of interventions is aimed at supporting socialisation through a “direct” approach, exposing the patients to social interactions and supervising them as they engage with new social contacts. Examples are social coaching interventions, peer supporting interventions and volunteering programs. These interventions have shown promising effects (Anderson et al., Citation2015) but are currently being evaluated in larger studies (Giacco et al., Citation2021; Gillard et al., Citation2020).

Other strategies have been described in relation to interventions primarily addressing loneliness (Lim et al., Citation2018; Lim & Gleeson, Citation2014; Ma et al., Citation2020). These could focus on addressing maladaptive cognition in social relationships, using positive affect to enhance social bonds and increasing accessibility to a positive social environment.

It has been suggested that some interventions incorporate strategies from different groups (Lim & Gleeson, Citation2014), i.e. including training in developing positive interpersonal styles during social skills training sessions; or contacts with volunteers or social coaching as a way towards (or intentionally engineered to) accessing positive social environments.

How can we measure what works?

Social isolation can be difficult to conceptualise and measure. Many interventions have been assessed using wider concepts of “social performance”, “social functioning” and “social disability” (Anderson et al., Citation2015; Turner et al., Citation2018), which do not allow a specific understanding of change in social interactions and networks.

Recent conceptual reviews and systematic reviews have clarified the different constructs used to define and quantify social isolation and, social connectedness (Lim et al., Citation2018; Michalska da Rocha et al., Citation2018; Palumbo et al., Citation2015; Siette et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2017).

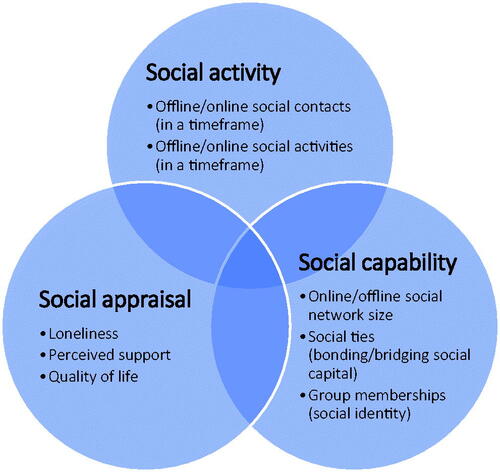

A framework is proposed here, which, whilst indebted to these prior research exercises, simplifies the grouping of constructs under three categories. Its simplicity may make it attractive for researchers who design evaluations of interventions and might enhance comparability of different studies. This, in turn, might help the selection of most promising interventions for the implementation in routine practice. This framework describes three groups of constructs, referring to the domains of “social activity”, “social capability” and “social appraisal”. These domains, and examples of the constructs which fall under them, are described in .

Social activity constructs refer to the amount of social contacts or activities in a timeframe (which can be, for example, one week, one month, etc.). These are usually reported by the research participant. These constructs can help to sensitively identify change following interventions (Fowler et al., 2018; Priebe et al., Citation2020). However, there are concerns that increased social activity, in itself, is not necessarily associated to long-standing improvements in social life or reduction of loneliness (Giacco et al., Citation2016; Ma et al., Citation2021) and that the data collected through these measures is affected by recall bias and cognitive difficulties (Bell et al., Citation2019).

Social capability constructs refer to the number and type of people that a person feels are part of his/her social networks. These can be assessed through social networks maps, asking people to name others with whom they feel they are in a social relationship (Dhand et al., Citation2019; Sweet et al., Citation2018). The social network maps can help to establish social influences on behaviours of individuals and how such behaviours (e.g. eating habits, substance use, see Christakis & Fowler, Citation2007; Knerich et al., Citation2019) or even personal feelings (e.g. loneliness, happiness, see Fowler & Christakis, Citation2008; Cacioppo et al., Citation2009) are propagated through networks. They also provide information on the social capital of people, which includes (Salehi et al., Citation2019) bonding capital, i.e. close family or friends, who can provide support; and bridging capital, i.e. people who are less socially close (e.g. acquaintances), but provide access to other social groups and larger social participation. The “social identity theory” identifies another aspect, which is the number and type of social groups people feel they belong to (Conneely et al., Citation2021). Studies have linked a higher number of social groups and higher strength of the connection to these groups to better mental health, i.e. lower incidence of depression and paranoia (McIntyre et al., Citation2018).

Social appraisal constructs are the ones that matter the most to service users and have certainly been studied in more detail in mental health research, i.e. loneliness, quality of life, and perceptions of social support. However, they can be influenced by symptoms such as depression or anxiety (Fakhoury & Priebe, Citation2002; Giacco et al., Citation2012; Lim et al., Citation2018), and hence improvements in loneliness or quality of life may not be directly consequent from socialisation and/or may be influenced by other factors.

How can the framework be useful?

Whilst relatively simple and only consisting of three domains, this framework can help us to understand and compare complex effects of interventions and/or design strategies for intervention and envisage their mechanism of action.

An example comes from a “social coaching intervention” (Giacco et al., Citation2021). This intervention aims, through solution-focused therapy and motivational interviewing techniques, to encourage and supervise patients to engage in their social activity of choice and through that meet more people (“social contacts”). Increasing social activity (e.g. increasing the number of social contacts on one week) can be a proximal outcome which may then be linked to higher social capability (i.e. increased social networks of participants, increased bridging social capital) and more positive social appraisals (i.e. improved quality of life).

On the other hand, interventions which improve appraisals (taking as example the loneliness interventions, described by Lim & Gleeson, Citation2014 with further theorisation in Lim et al., Citation2018) might increase confidence of people towards social interactions and hence enhance social activity and, as a consequence, social capability.

Finally, interventions based on volunteering or peer support (Gillard et al., Citation2020; Priebe et al., Citation2020) which indeed, add “new social contacts” (volunteers or peers) and hence increase social capability (although usually for limited periods of time), might generate high social activity and/or improvement of appraisals.

Understanding the effects of these interventions can help to either select the most promising ones or develop more complex and integrated interventions including components which address different outcomes in order to maximise overall effectiveness.

This framework can also help to design interventions and studies which make use of the increased opportunities for activation of pro-social behaviours and for their accurate measurement. These opportunities are being offered by societal changes and novel digital technologies.

Opportunities and challenges ahead

“New” social interactions

Online social interactions have been a part of our life for a long time, but the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly caused a step change in how frequently and confidently most people use them (Bonsaksen et al., Citation2021; Geirdal et al., Citation2021). Initial studies have suggested that people with psychosis may not struggle with online social interactions as much as they do with offline social interactions (Highton-Williamson et al., Citation2015; Jakubowska et al., Citation2019). The field of online interventions for psychosis is flourishing (Álvarez-Jiménez et al., Citation2012, Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2021).

However, the question as to whether increased online social activity and networks result in more positive appraisals of one’s own social life remains very much a field for scientific investigation, not only in clinical populations (Bonsaksen et al., Citation2021; Geirdal et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, many recent intervention models have been specifically designed (e.g. Lim et al., Citation2018) or adapted during the pandemic (e.g. Giacco et al., Citation2021) for online or hybrid delivery. The effect of the delivery format (online, offline or hybrid) on access, outcomes and feasibility variables is likely to become a recurrent question in the evaluation of the effectiveness and implementation of interventions.

“New” evaluation methods

Ecological Momentary Assessments (EMA) have been used for few decades now to assess experiences and activities of people with psychosis outside of clinical environments (Bell et al., Citation2017; Granholm et al., Citation2020). They have to some extent changed our understanding of the problems of people with psychosis in social interactions. For example, it has been established that people with psychosis consistently report experiencing pleasure from social activities when this is measured via EMA and this pleasure is comparable to that experienced by healthy controls (Mote & Fulford, Citation2020). EMA can also be used to assess prospectively social contacts (rather than retrospectively) which can reduce the effect of cognitive difficulties and recall bias on current social activity measures (Bell et al., Citation2019). EMA using sensors can even detect social interactions without the need for participant reports (Lucet et al., Citation2012). Finally, Ecological Momentary Interventions (EMI) have been developed to improve a number of outcomes for people with schizophrenia (Myin-Germeys et al., Citation2016). EMI seem promising towards resolving the “translation” problems of previous interventions, i.e. the disconnection between positive effects in clinic-based outcomes and limited improvement in real-world social connections (Anderson et al., Citation2015; Turner et al., Citation2018).

Conclusions

Decades of research have addressed the problem of social isolation of people with psychotic disorders. Many interventions have been developed to reduce social isolation and shown promise. None of them has a definitive evidence base or is widely implemented in routine practice. A framework was proposed to categorise and link the different constructs within the social isolation “umbrella” so that the complex effects of interventions can be understood and compared. Conceptual clarity and comparability across studies can generate rapid advances in this field. This is particularly important, as societal changes and new technologies are offering new prospects for how we can measure and intervene on social isolation, and help people with psychosis to improve their social life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Álvarez-Jiménez, M., Gleeson, J. F., Bendall, S., Lederman, R., Wadley, G., Killackey, E., & McGorry, P. D. (2012). Internet-based interventions for psychosis: A sneak-peek into the future. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 35(3), 735–747. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2012.06.011

- Álvarez-Jiménez, M., Koval, P., Schmaal, L., Bendall, S., O'Sullivan, S., Cagliarini, D., D'Alfonso, S., Rice, S., Valentine, L., Penn, D. L., Miles, C., Russon, P., Phillips, J., McEnery, C., Lederman, R., Killackey, E., Mihalopoulos, C., Gonzalez-Blanch, C., Gilbertson, T., … Gleeson, J. (2021). The Horyzons project: A randomized controlled trial of a novel online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from specialist first-episode psychosis services. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20858

- Anderson, K., Laxhman, N., & Priebe, S. (2015). Can mental health interventions change social networks? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0684-6

- Barnes, T. R., Drake, R., Paton, C., Cooper, S. J., Deakin, B., Ferrier, IN., Gregory, C. J., Haddad, P. M., Howes, O. D., Jones, I., Joyce, E. M., Lewis, S., Lingford-Hughes, A., MacCabe, J. H., Owens, D. C., Patel, M. X., Sinclair, J. M., Stone, J. M., Talbot, P. S., … Yung, A. R. (2020). Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: Updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 34(1), 3–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119889296

- Bell, I. H., Lim, M. H., Rossell, S. L., & Thomas, N. (2017). Ecological momentary assessment and intervention in the treatment of psychotic disorders: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 68(11), 1172–1181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600523

- Bell, A., Ward, P., Tamal, M., & Killilea, M. (2019). Assessing recall bias and measurement error in high-frequency social data collection for human-environment research. Population and Environment, 40, 325–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-019-0314-1

- Bonsaksen, T., Ruffolo, M., Leung, J., Price, D., Thygesen, H., Schoultz, M., & Geirdal, A. Ø. (2021). Loneliness and its association with social media use during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social Media+, 7(3), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211033821

- Cacioppo, J. T., Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2009). Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 977–991. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016076

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(4), 370–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa066082

- Cogan, N. A., MacIntyre, G., Stewart, A., Tofts, A., Quinn, N., Johnston, G., Hamill, L., Robinson, J., Igoe, M., Easton, D., McFadden, A. M., & Rowe, M. (2021). “The biggest barrier is to inclusion itself”: The experience of citizenship for adults with mental health problems. Journal of Mental Health, 30(3), 358–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1803491

- Conneely, M., McNamee, P., Gupta, V., Richardson, J., Priebe, S., Jones, J. M., & Giacco, D. (2021). Understanding identity changes in psychosis: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(2), 309–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa124

- Dhand, A., Lang, C. E., Luke, D. A., Kim, A., Li, K., McCafferty, L., Mu, Y., Rosner, B., Feske, S. K., & Lee, J. M. (2019). Social network mapping and functional recovery within 6 months of ischemic stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 33(11), 922–932. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968319872994

- Douglas, C., Wood, L., & Taggart, D. (2022). Recovery priorities of people with psychosis in acute mental health in-patient settings: A Q-methodology study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 50(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000892

- Fakhoury, W. K., & Priebe, S. (2002). Subjective quality of life: Its association with other constructs. International Review of Psychiatry, 14(3), 219–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260220144957

- Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 337, a2338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2338

- Fowler, D., Hodgekins, J., French, P., Marshall, M., Freemantle, N., McCrone, P., Everard, L., Lavis, A., Jones, P. B., Amos, T., Singh, S., Sharma, V., & Birchwood, M. (2018). Social recovery therapy in combination with early intervention services for enhancement of social recovery in patients with first-episode psychosis (SUPEREDEN3): A single-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 5(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30476-5

- Geirdal, A. O., Ruffolo, M., Leung, J., Thygesen, H., Price, D., Bonsaksen, T., & Schoultz, M. (2021). Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. Journal of Mental Health, 30(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1875413

- Giacco, D., Chevalier, A., Patterson, M., Hamborg, T., Mortimer, R., Feng, Y., Webber, M., Xanthopoulou, P., & Priebe, S. (2021). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a structured social coaching intervention for people with psychosis (SCENE): Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 11(12), e050627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050627

- Giacco, D., McCabe, R., Kallert, T., Hansson, L., Fiorillo, A., & Priebe, S. (2012). Friends and symptom dimensions in patients with psychosis: A pooled analysis. PLoS One, 7(11), e50119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050119

- Giacco, D., Palumbo, C., Strappelli, N., Catapano, F., & Priebe, S. (2016). Social contacts and loneliness in people with psychotic and mood disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 66, 59–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.12.008

- Gillard, S., Bremner, S., Foster, R., Gibson, S. L., Goldsmith, L., Healey, A., Lucock, M., Marks, J., Morshead, R., Patel, A., Priebe, S., Repper, J., Rinaldi, M., Roberts, S., Simpson, A., & White, S. (2020). Peer support for discharge from inpatient to community mental health services: Study protocol clinical trial (SPIRIT Compliant). Medicine, 99(10), e19192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019192

- Granholm, E., Holden, J. L., Mikhael, T., Link, P. C., Swendsen, J., Depp, C., Moore, R. C., & Harvey, P. D. (2020). What do people with schizophrenia do all day? Ecological momentary assessment of real-world functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(2), 242–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz070

- Highton-Williamson, E., Priebe, S., & Giacco, D. (2015). Online social networking in people with psychosis: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014556392

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Jakubowska, A., Kaselionyte, J., Priebe, S., & Giacco, D. (2019). Internet use for social interaction by people with psychosis: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(5), 336–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0554

- Knerich, V., Jones, A. A., Seyedin, S., Siu, C., Dinh, L., Mostafavi, S., Barr, A. M., Panenka, W. J., Thornton, A. E., Honer, W. G., & Rutherford, A. R. (2019). Social and structural factors associated with substance use within the support network of adults living in precarious housing in a socially marginalized neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One, 14(9), e0222611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222611

- Lamster, F., Nittel, C., Rief, W., Mehl, S., & Lincoln, T. (2017). The impact of loneliness on paranoia: An experimental approach. The Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 54, 51–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.06.005

- Lim, M. H., & Gleeson, J. F. (2014). Social connectedness across the psychosis spectrum: Current issues and future directions for interventions in loneliness. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, 154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00154

- Lim, M. H., Gleeson, J., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., & Penn, D. L. (2018). Loneliness in psychosis: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1482-5

- Lucet, J. C., Laouenan, C., Chelius, G., Veziris, N., Lepelletier, D., Friggeri, A., Abiteboul, D., Bouvet, E., Mentre, F., & Fleury, E. (2012). Electronic sensors for assessing interactions between healthcare workers and patients under airborne precautions. PLoS One, 7(5), e37893. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037893

- Ma, R., Mann, F., Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Terhune, J., Al-Shihabi, A., & Johnson, S. (2020). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 839–876. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01800-z

- Ma, R., Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Marston, L., & Johnson, S. (2021). Trajectories of loneliness and objective social isolation and associations between persistent loneliness and self-reported personal recovery in a cohort of secondary mental health service users in the UK. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03430-9

- McIntyre, J. C., Wickham, S., Barr, B., & Bentall, R. P. (2018). Social identity and psychosis: Associations and psychological mechanisms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(3), 681–690. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx110

- Michalska da Rocha, B., Rhodes, S., Vasilopoulou, E., & Hutton, P. (2018). Loneliness in Psychosis: A meta-analytical review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx036

- Mote, J., & Fulford, D. (2020). Ecological momentary assessment of everyday social experiences of people with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 216, 56–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.021

- Myin-Germeys, I., Klippel, A., Steinhart, H., & Reininghaus, U. (2016). Ecological momentary interventions in psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(4), 258–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000255

- Palumbo, C., Volpe, U., Matanov, A., Priebe, S., & Giacco, D. (2015). Social networks of patients with psychosis: A systematic review. BMC Research Notes, 8, 560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1528-7

- Pantell, M., Rehkopf, D., Jutte, D., Syme, S. L., Balmes, J., & Adler, N. (2013). Social isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), 2056–2062. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261

- Priebe, S., Chevalier, A., Hamborg, T., Golden, E., King, M., & Pistrang, N. (2020). Effectiveness of a volunteer befriending programme for patients with schizophrenia: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatr, 217(3), 477–483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.42

- Salehi, A., Ehrlich, C., Kendall, E., & Sav, A. (2019). Bonding and bridging social capital in the recovery of severe mental illness: A synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Mental Health, 28(3), 331–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466033

- Siette, J., Gulea, C., & Priebe, S. (2015). Assessing social networks in patients with psychotic disorders: A systematic review of instruments. PLoS One, 10(12), e0145250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145250

- Simblett, S. K., Wilson, E., Morris, D., Evans, J., Odoi, C., Mutepua, M., Dawe-Lane, E., Jilka, S., Pinfold, V., & Wykes, T. (2021). Keeping well in a COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study formulating the perspectives of mental health service users and carers. Journal of Mental Health, 30(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1875424

- Singh, S. P., Mohan, M., & Giacco, D. (2021). Psychosocial interventions for people with a first episode psychosis: Between tradition and innovation. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(5), 460–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000726

- Sweet, D., Byng, R., Webber, M., Enki, D. G., Porter, I., Larsen, J., Huxley, P., & Pinfold, V. (2018). Personal well-being networks, social capital and severe mental illness: Exploratory study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(5), 308–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.117.203950

- Tee, H., Priebe, S., Santos, C., Xanthopoulou, P., Webber, M., & Giacco, D. (2020). Helping people with psychosis to expand their social networks: The stakeholders' views. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2445-4

- Turner, D. T., McGlanaghy, E., Cuijpers, P., van der Gaag, M., Karyotaki, E., & MacBeth, A. (2018). A meta-analysis of social skills training and related interventions for psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(3), 475–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx146

- van der Werf, M., van Winkel, R., van Boxtel, M., & van Os, J. (2010). Evidence that the impact of hearing impairment on psychosis risk is moderated by the level of complexity of the social environment. Schizophrenia Research, 122(1–3), 193–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.020

- Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Giacco, D., Forsyth, R., Nebo, C., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2017). Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1451–1461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

- Wood, L., & Alsawy, S. (2018). Recovery in psychosis from a service user perspective: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of current qualitative evidence. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(6), 793–804. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0185-9