Abstract

Background

There is increasing interest in the association between nature, health and wellbeing. Gardening is a popular way in which interaction with nature occurs and numerous gardening projects aim to facilitate wellbeing among participants. More research is needed to determine their effectiveness.

Aim

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of group-based gardening interventions for increasing wellbeing and reducing symptoms of mental ill-health in adults.

Methods

A systematic review of Randomised Controlled Trials was conducted following the protocol submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020162187). Studies reporting quantitative validated health and wellbeing outcomes of the community residing, adult populations (18+) were eligible for inclusion.

Results

24 studies met inclusion criteria: 20 completed and four ongoing trials. Meta-analyses suggest these interventions may increase wellbeing and may reduce symptoms of depression, however, there was uncertainty in the pooled effects due to heterogeneity and unclear risk of bias for many studies. There were mixed results for other outcomes.

Research limitations/implications

Heterogeneity and small sample sizes limited the results. Poor reporting precluded meta-analysis for some studies. Initial findings for wellbeing and depression are promising and should be corroborated in further studies. The research area is active, and the results of the ongoing trials identified will add to the evidence base.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the way in which nature and green space can promote human health and wellbeing (Clatworthy et al., Citation2013). The evidence for the health benefits of gardening is associated with this wider body of literature (Buck, Citation2016). Ecological models of health, such as Barton and Grant (Citation2006) Health Map, illustrate the influence that the natural environment has, above all other determinants of health, in providing the context in which we live our lives, including the provision of ecosystem services and opportunities for health-promoting behaviours. Consequently, health interventions that utilise nature as a way of public health promotion have the potential to result in wide-reaching positive effects for both people and the planet (Dean et al., Citation2011; Harris, Citation2017). This growing interest in the relationship between humans and the environment has led to the identification of a new research paradigm: 'Human health-environment interaction science’, a transdisciplinary approach that encompasses both the effects of humans on the environment and the effect of the environment on human health and wellbeing (Spano et al., Citation2020a).

In addition, the current interest in social prescribing, a method of linking patients to non-clinical support within their communities to address the complex multimorbidity and psycho-social needs of patients, represents an opportunity for wider implementation of these interventions across the UK (Howarth et al., Citation2020; Thomson et al., Citation2015). As a result, it is essential to determine the effectiveness of gardening interventions and to ensure that the evidence base reflects what is considered quality evidence in the field of medicine and public health.

For the purpose of this review, gardening interventions are defined as organised programmes of group-based gardening activities. This definition includes Social and Therapeutic Horticulture (STH) projects, which aim to use gardening activities to improve the general wellbeing of participants (Sempik, Citation2010) as well as horticultural therapy, which can be distinguished from STH due to its focus on achieving clinical goals and facilitation by therapists trained in horticulture (Cipriani et al., Citation2017; Sempik, Citation2010). However, in practice, there is likely to be some overlap between these two types of interventions (Annerstedt & Währborg, Citation2011).

Background

The salutogenic effects of natural environments are often explained by their restorative qualities whereby restoration is the “process of renewing, recovering or re-establishing physical, psychological and social resources or capabilities” (Hartig, Citation2004; 273). Two well-evidenced and prominent theories seek to explain the mechanisms through which natural environments facilitate restoration: the Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) (Ulrich, Citation1984; Ulrich et al., Citation1991) and the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) (Kaplan, Citation1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989).

Ulrich’s (Citation1984) Stress Reduction Theory, suggests this restorative quality results from the natural stimuli found in nature which activates the parasympathetic nervous system, facilitating psycho-physiological stress recovery.

The Attention Restoration Theory (ART) (Kaplan, Citation1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989) proposes that natural environments, and the stimuli they expose us to, facilitate a person-environment interaction, which can restore the capacity for directed attention, by activating involuntary attention (Kaplan, Citation1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989). The outcome of which is greater positive affect, less negative affect and due to a reduction in mental fatigue, renewed capacity for cognitive tasks.

These psycho-evolutionary theories are related to Wilson’s (Citation1984) Biophilia Hypothesis which proposes humans’ innate affiliation with nature as a result of physiological and psychological evolutionary adaption to natural environments. Both are frequently used to explain how gardening and gardening interventions can benefit health, especially in relation to psychological outcomes. However, Harris (Citation2017) argues that such theories often dominate the literature, overshadowing the contributions of other aspects of the interventions, for example, the physical activity and social interaction they facilitate.

As Hartig et al. (Citation2014) explain, it is likely that the proposed mechanisms for how gardening interventions can benefit health interact with each other. Similarly, Sempik (Citation2010) emphasises that it is a result of the interaction of the various components of gardening interventions: the activities, the setting, and the social environment, that makes them therapeutic. Gardening-based interventions, including horticultural therapy, can incorporate other activities that may not be directly related to gardening, such as mindfulness or craft activities (Corazon et al., Citation2010; Harris, Citation2017; Sempik, Citation2010).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on gardening interventions for psychosocial wellbeing, which assessed outcomes such as trust, social cooperation and social networks, found positive results, with moderate effects reported (Spano et al., Citation2020b). The findings provide quantitative evidence of the benefit of such interventions for psychosocial outcomes and can also lend support to the importance of the community and social aspects of these interventions for wellbeing outcomes. The results also align with the findings of Soga et al. (Citation2017) meta-analysis into the benefits of gardening outdoors for health, where an overall significant positive effect was found from the results of 21 quantitative studies (76 comparisons). Sub-group analysis also demonstrated significant benefits, with the greatest effect sizes reported on wellbeing variables, when participants were patients, and where the gardening type was described as a therapy.

Of the reviews that have focused on gardening interventions for adults’ mental health (see Cipriani et al., Citation2017; Clatworthy et al., Citation2013; Kamioka et al., Citation2014) all have reported positive effects of the interventions. However, the authors highlighted the various limitations of the included studies which impacted the conclusions that could be drawn from the results. For example, while the studies in Clatworthy et al. (Citation2013) review all reported positive effects, such as significant reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety, the lack of control groups in many of the studies led the authors to conclude that research methods more suited to asserting causation were required. Similarly, the four Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) assessed by Kamioka et al. (Citation2014) all reported some positive outcomes, for example, reductions in symptoms of depression, which led the authors to conclude that horticultural therapy may be effective for a range of mental health conditions. However, due to the small number of studies and heterogeneity of the populations, they also concluded that more evidence was needed. More recently, Cipriani et al. (Citation2017) review, which focussed on horticultural therapy recommended its wider use within occupational therapy. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledged the various methodological and reporting limitations of the studies, and that the population group was predominantly older adults.

Since these reviews, there has been an increase in the quality and quantity of research in the field which represents an opportunity to reassess the effectiveness of gardening interventions for improving adults’ mental health and wellbeing and further the evidence base for this research area so that the policy implications highlighted by many authors in the field have the potential to be realised (Buck, Citation2016; Howarth et al., Citation2020; Sempik et al., Citation2010; Soga et al., Citation2017; Thompson, Citation2018).

Methodology

Aim

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of gardening interventions for increasing wellbeing and reducing symptoms of mental ill-health in adults.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted in line with the protocol submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020162187).

Search strategy

The search was conducted in the following databases from database inception to 10th July 2021 PsychINFO; Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE); Web of Science Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE). Trial registers (WHO ICTRP and Clinicaltrials.gov) were also searched to identify ongoing trials. Reference lists of included studies were hand searched to identify any further studies.

The following text word terms were used to search each database: ("Garden*" OR "Horticultur*" OR "Nature based") AND (“Therap*” OR “Program*” OR “Intervention*” OR “Group*” OR “Project*” OR “Activit*” Or “Course*” OR “Rehabilitat*” OR “Recover*” OR “Restor*”) AND (“Mental health” OR “Mental illness*” OR “Wellbeing” OR “Well-being” OR “Anxi*” OR “Depress*” OR “Stress” OR “Distress”).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created in line with the PICOS approach (Centre for Reviews & Dissemination, Citation2008) and studies were independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (RB & KR) for all stages (screening titles and abstracts, full-text reviews, data extraction and quality appraisal).

Participants/Population

Adults of any age (18+) and ethnicity living in the community. A mental health diagnosis was not a requirement for inclusion. Previous reviews have focused on interventions within residential care settings and people with dementia, therefore these groups were excluded (see Nicholas et al., Citation2019; Wang & MacMillan, Citation2013; Yeo et al., Citation2020).

Intervention

Participation in any gardening intervention; an organised programme of group-based and time-bound gardening activities. The interventions must be led by someone in a coordinating role. No exclusion was set based on the level of therapist input. Gardening interventions that also included non-gardening activities were included if gardening was considered to form the majority of the intervention.

Comparator/Control

The control group condition could include individuals undertaking another type of intervention, those on a waitlist, no treatment or treatment/care as usual.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported on mental health, wellbeing and/or quality of life outcomes using validated scales administered pre and post-intervention.

Types of studies included

Randomised controlled trials.

Quality appraisal

The Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB) tool (Higgins et al., Citation2011) was used by two independent reviewers (RB & KR); where any disagreements were discussed and resolved. Due to the nature of the interventions, whereby participants and personnel cannot be blinded to group allocation, the studies have not been downgraded for this and an assessment of blinding has been conducted in relation to blinding of those collecting and analysing the data. The results are presented in Robvis format in (McGuinness & Higgins, Citation2021).

Table 1. Risk of Bias table.

Data extraction

Data were extracted in duplicate into excel tables that had been piloted. The data includes general information about the study, a description of the intervention and information about the control group, participant characteristics, health and wellbeing outcomes measured, data reported and, scales used. Efforts were made to contact authors where there was missing data.

Data analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to pool findings for each outcome using random effects models in RevMan 5.4 (Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, Citation2020). Standardised mean differences were calculated as different validated scales reported our outcomes of interest. Where heterogeneity precluded a meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis following the guidance in the Cochrane handbook was performed (McKenzie et al., Citation2021).

Results

Selection process

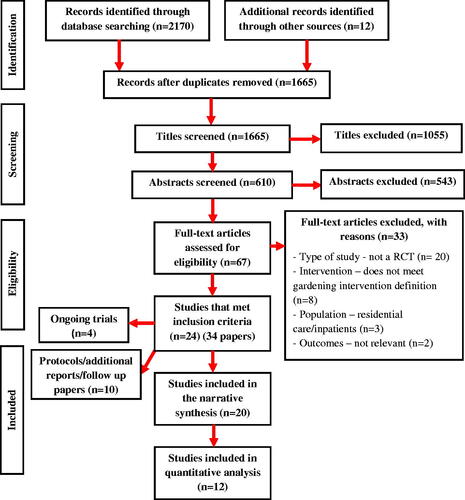

The PRISMA flow diagram (The PRISMA Group, Citation2009) provides a visual representation of the screening process and the number of studies included/excluded at each stage ().

Description of included studies

The key characteristics of the 20 studies are presented in . 11/20 were published in the last four years. Five of the studies were published in the USA (Brown et al., Citation2020; Demark-Wahnefried et al., Citation2018; Detweiler et al., Citation2015; Odeh & Guy, Citation2018; Okvat, Citation2011) five were published in Japan (Kotozaki, Citation2013a; Citation2013b; Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Makizako et al., Citation2019) three in China (Huang et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Siu et al., Citation2020) and the remaining were published in Sweden (Bay-Richter et al., Citation2012; Pálsdóttir et al., Citation2020) Serbia (Vujcic et al., Citation2017; Citation2021) Denmark (Stigsdotter et al., Citation2018) Singapore (Ng et al., Citation2018) and South Korea (Kim & Park, Citation2018).

Table 2. Description of included studies.

Across the 20 published studies, the total number of participants included in the data analysis was 874. In individual studies, the sample size ranged from 20 (Brown et al., Citation2020) to 89 (Pálsdóttir et al., Citation2020). Most studies included a wide age range, e.g. 18–65 or 50–80, where overall the estimated mean of mean ages reported was 50.7 years. In 10/20 of the studies, participants had either diagnosed mental health conditions or mental health symptoms. Of the remaining 10 studies, participants had diagnoses of diabetes (Brown et al., Citation2020), was recovering from stroke (Pálsdóttir et al., Citation2020), cancer (Demark-Wahnefried et al., Citation2018), post-operative hand trauma (Huang et al., Citation2018) or suffered damage following an earthquake (Kotozaki, Citation2014a). In five studies participants had no reported health difficulties (Kim & Park, Citation2018; Kotozaki, Citation2013a; Ng et al., Citation2018; Odeh & Guy, Citation2018; Okvat, Citation2011).

Depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life, wellbeing and affect, were relevant outcomes assessed by the studies. Various validated scales were used (see , for outcome data, see ). Four ongoing studies, with larger sample sizes and study completion, dates from December 2021 also met the inclusion criteria, their details are presented in .

Table 3. Available data from included studies.

Table 4. Description of ongoing trials.

Methodological quality

The risk of bias appraisal () indicated that seven studies had a low risk of bias and the remainder were at unclear risk of bias. Lack of reporting, whereby information necessary to determine risk rating was not included in the paper, was the predominant reason for rating studies as ‘unclear’ risk. Two studies were published only in abstract form and due to lack of information with which to access the risk of bias, both were rated as ‘unclear’.

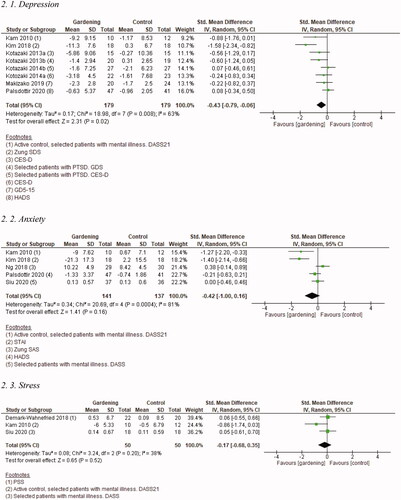

Depression

Eight studies (358 participants randomised) reported data on depression in a format suitable for meta-analysis (See . Depression). Three of the eight studies selected patients with mental illness (Kam & Siu, Citation2010, Kotozaki, Citation2013b, Kotozaki, Citation2014b). There was substantial heterogeneity and so uncertainty in the pooled effect estimate, where four trials reported positive effects of the intervention on depression and the remaining four had little or no effect.

Figure 2. Forest Plots of health and wellbeing outcomes.

Seven further studies reported the effects of gardening interventions on depression, but data were not in a format suitable for meta-analysis. Where available, data from these studies are reported in . In two studies data were not presented to calculate change from baseline to follow-up (Detweiler et al., Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2018), and two had insufficient data as were reported only as abstracts (Bay-Richter et al., Citation2012; Huang et al., Citation2018), in one study the full paper did not present numerical data (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018) and in the remaining two studies, data were presented as either medians or comparison of variances (Brown et al., Citation2020; Vujcic et al., Citation2017). Four of the seven studies compared gardening interventions to inactive controls (Bay-Richter et al., Citation2012; Brown et al., Citation2020; Huang et al., Citation2018; Ng et al., Citation2018), and three to active comparators including occupational therapy (Detweiler et al., Citation2015; Vujcic et al., Citation2017) or group art therapy (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018). Two studies selected patients with mental illness (Bay-Richter et al., Citation2012; Vujcic et al., Citation2017) and one selected veterans with substance abuse disorders (Detweiler et al., Citation2015), the remaining studies recruited healthy women (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018), native Americans with pre-diabetes or diabetes (Brown et al., Citation2020), those with hand trauma undergoing rehabilitation (Huang et al., Citation2018), and older adults (Ng et al., Citation2018). Overall, findings were mixed with one study showing beneficial effects of gardening interventions on depression compared to control (Huang et al., Citation2018), another reporting improvements in depression with both gardening and the active comparator arts therapy, but with no analysis between groups (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018), and the remaining studies reporting little or no effect of gardening interventions on depression compared to control.

Anxiety

Five studies (278 participants randomised) reported data on anxiety in a format suitable for meta-analysis (See . Anxiety). Two of five studies selected patients with mental illness (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Siu et al., Citation2020). There was considerable heterogeneity and so uncertainty in the pooled effect estimate, where two trials reported positive effects of the intervention on anxiety and the remaining three had little or no effect. Two further studies assessed the effect of gardening interventions on anxiety but did not have data in a usable format for meta-analysis. One study (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018) where participants were healthy women found no statistically significant changes between pre and post-scores for either the gardening or art therapy group and did not analyse differences between groups. The remaining study (Vujcic et al., Citation2017) selected participants with mental illness and did not find significant interactions between pre and post-tests or groups (gardening and occupational therapy) for anxiety.

Stress

Three studies (100 participants randomised) all of which had a low risk of bias, reported data on stress in a format suitable for meta-analysis (See . Stress). Two of the studies selected patients with mental illness (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Siu et al., Citation2020) though in the later, stress levels were low at baseline. Overall, the pooled effect estimate shows little or no effect of the intervention on stress (SMD −0.17 (95%CI to 0.68, 0.35)). Two further studies reported on stress but not in a format suitable for meta-analysis (Odeh & Guy, Citation2018; Vujcic et al., Citation2017). Odeh and Guy (Citation2018) found improvements in stress for both the gardening and art therapy conditions but did not analyse differences between groups. Vujcic et al. (Citation2017) recruited participants with mental illness and found a significant interaction between tests (pre and post) and groups (gardening and occupational therapy) demonstrating a reduction in stress with gardening (P = 0.027).

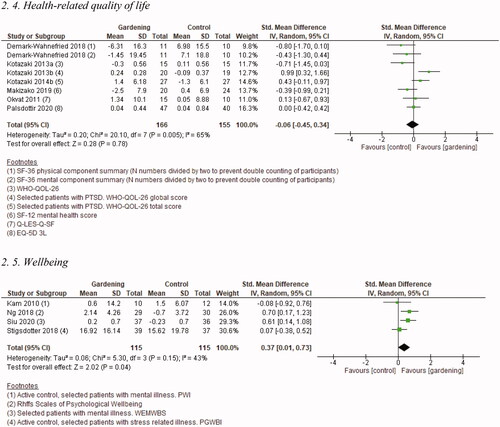

Health-related quality of life

Seven studies (321 participants randomised) reported data on health-related quality of life in a format suitable for meta-analysis (See . Health-related quality of life). There was substantial heterogeneity and so uncertainty in the pooled effect estimate, two trials, both with unclear risk of bias, reported positive effects of the intervention on quality of life, and the remaining five had little or no effect. Three further studies that did not have data in a usable format for meta-analysis also reported on this outcome (Brown et al., Citation2020; Detweiler et al., Citation2015; Odeh & Guy, Citation2018). None of these studies found significant differences in quality of life between comparison groups.

Wellbeing

Four studies (230 participants randomised) all with a low risk of bias, reported data on wellbeing in a format suitable for meta-analysis (See . Wellbeing). Three of the four studies selected patients with mental illness (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Siu et al., Citation2020; Stigsdotter et al., Citation2018). Overall, the pooled effect estimate shows an increase in wellbeing with gardening interventions (SMD 0.37 (95%CI 0.01 to 0.73)).

Affect related outcomes

Five studies included affect-related outcomes such as mood disturbance and positive and negative affect, data for which is presented in . Four of the studies included participants with no mental health conditions (Brown et al., Citation2020; Kotozaki, Citation2013a; Odeh & Guy, Citation2018; Okvat, Citation2011). Brown et al. (Citation2020) reported a statistically significant difference between the groups for total mood disturbance while Odeh and Guy (Citation2018) and Kotozaki (Citation2013a) found no significant differences. Similarly, Okvat (Citation2011) reported no significant differences between groups however, in this study, scores were already high for positive affect and low for negative affect at baseline. Kotozaki (Citation2013b) included women with PTSD symptoms and found a significant improvement in positive affect but not for negative affect when compared to a stress control intervention.

Other relevant outcomes

Burnout was assessed by Stigsdotter et al. (Citation2018) significant reductions in burnout were observed for both the gardening intervention group and CBT control group with no significant difference between them. The Global Impression scale was used by Vujcic et al. (Citation2021) to assess the severity of mental illness in a study of people with diagnosed mental health conditions. Baseline scores of both groups reflected moderate illness. In the intervention group, scores decreased following the intervention reflecting ‘minimal improvement’ while no change was observed in the occupational therapy control group.

Kotozaki (Citation2013a; Citation2014a; Citation2014b) assessed the mental health of participants using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). A significant decrease in GHQ scores (improvement in mental health) was observed among young adults without mental health conditions taking part in a group gardening intervention when compared to both those assigned to the individual gardening intervention as well as the control condition (Kotozaki, Citation2013a). No significant effect of the intervention on GHQ was observed in the two remaining studies (Kotozaki, Citation2014a; Citation2014b).

Two studies by Kotozaki (Citation2013b; 2014b) assessed the effect of gardening interventions for women with PTSD using the Clinician Administered PDSD scale, both found a statistically significant effect of the intervention on symptoms.

Discussion

The results of this systematic review on the effects of gardening interventions on mental health and wellbeing are mixed. The current evidence indicates positive effects of group-based gardening interventions on depression and wellbeing, but these results need to be corroborated in larger sufficiently powered studies. No overall effects were seen on measures of anxiety, stress or quality of life when compared with active and inactive controls or those selected with mental illness, but numbers were small for both stress and anxiety. The most promising results were observed for wellbeing, showing significant improvements in the pooled effect estimate of four trials, all with a low risk of bias. Effects on wellbeing were largest for studies using inactive comparators, those using active comparators recruited participants with mental illness. Further studies are needed to corroborate these initial findings. The results of the four ongoing studies we identified and the conduct of additional high-quality studies will add to the evidence base and reduce uncertainty in the findings.

While the results are limited, the present review expands upon previous reviews by focussing exclusively on RCTs, reflecting advances in the quality of evidence in the field, as well as including a greater number of studies, several of which were published in recent years, which demonstrates an active research area. The results of this review also support and reaffirm those found in past reviews of gardening interventions for mental health, where positive effects were also found among various outcomes, including depression and anxiety (Cipriani et al., Citation2017; Clatworthy et al., Citation2013; Kamioka et al., Citation2014). However, methodological limitations and heterogeneity limited the conclusions that were able to be drawn from the results. The current review’s focus on RCTs and use of meta-analysis overcome many of the previously identified limitations, nonetheless, further high-quality trials are needed to make definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of these interventions for mental health. However, stronger conclusions have been made in other areas. For example, Spano et al. (Citation2020b) found positive effects of gardening interventions for psychosocial outcomes such as trust and social networking, which may, in turn, lead to positive effects on participants mental health and wellbeing.

The positive findings in this present review regarding wellbeing also support the results of Soga et al. (Citation2017) meta-analysis, where a significant positive effect of gardening on health was found. The authors’ sub-group analysis identified a statistically significant difference in the effect sizes of wellbeing variables compared to physical health variables, with wellbeing variables observing a greater effect size. Soga et al. (Citation2017) hypothesised that physical health outcomes may take longer to respond to change. While this present review did not include physical health outcomes, this may nonetheless help to explain why some outcomes, such as health-related quality of life, showed less improvement than others.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of the current review is the heterogeneity of the included studies, in particular the diversity of the gardening interventions; including their structure, duration, frequency and follow-up periods. Additionally, there were few studies reporting on each outcome except for depression and quality of life where there was substantial heterogeneity and so, uncertainty in the pooled effect estimates. For most studies, the sample sizes were small and so were subject to small study bias where larger effects are seen for smaller trials (Sterne et al., Citation2000). This needs to be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings.

One of the strengths of the review is its inclusion of only RCTs, many of which were published in recent years, which provides stronger evidence than was previously available, as well as a greater number of total studies than earlier reviews. We attempted to increase the precision of our findings by using meta-analysis where possible. For some outcomes, notably depression, several studies were not suitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis. This was due to a lack of reporting of data in a useable format, either missing baseline or follow-up data, lack of numerical reporting or use of alternative analyses. Where meta-analysis was possible, heterogeneity limited the interpretation of findings with pooled effect estimates reported only for stress, wellbeing, and quality of life where heterogeneity was either moderate or absent. We used Standardised Mean Difference as a measure of intervention effect as, whilst all scales measuring mental health and wellbeing were validated, several different scales were used for each outcome.

Recommendations for future research

It is recommended that future research focus on larger, well-reported trials as this would help further the evidence base, reduce uncertainty in the findings and make more definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of such interventions. Evidence is currently limited to predominantly small trials at unclear risk of bias. Trials of both healthy participants and people with poor mental health would be valuable to determine the effects on both groups. It is recommended that where trials include participants with mental health conditions, their baseline scores reflect this. In some of the included trials participants had low levels of symptoms at baseline (e.g. Ng et al., Citation2018; Pálsdóttir et al., Citation2020; Siu et al., Citation2020). This may have indicated sample bias and limited opportunity for improvement following the interventions.

Implications for practice and policy

While promising effects were seen for wellbeing and possibly also depression, no definitive conclusions can be made about the effectiveness of such interventions currently. Consequently, no recommendations can be made about their use more widely. Nonetheless, there are already numerous such projects being offered by various charities and organisations, as such, it would be reasonable for future studies to evaluate these interventions to help further the evidence base. This would align with the UK Government’s 25-Year Environment Plan, which highlights the need to understand how environmental therapies could be integrated into mental health services (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, Citation2018). The research area is active as evidenced by the four ongoing studies we have identified. If in the future, the evidence finds group-based gardening interventions to be effective, they could help to contribute to reducing the burden of mental ill health in society either integrated within tiered mental health services or facilitated as social prescribing schemes.

Conclusion

The findings of this review include mixed results for the effectiveness of group-based gardening interventions for mental health and wellbeing. Results for wellbeing and depression are promising, with further studies needed to corroborate these findings among both general population participants and those with identified poor mental health. More studies, with a focus on larger, well conducted and well-reported trials, are needed to confirm initial findings and to determine the effectiveness of these interventions on other health outcomes where results are less clear.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rowena Stewart for her help with devising the search strategy.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- A Dose of Nature: An Interdisciplinary Study of Green Prescriptions (2019). Identification number NCT04175561. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04175561?term=a+dose+of+nature&draw=2&rank=1

- Annerstedt, M., & Währborg, P. (2011). Nature-assisted therapy: Systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810396400

- Assessing the Effect of Environmental Activity on Depressive Symptoms (2020). Identification number IRCT20181206041871N1. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=IRCT20181206041871N1

- Barton, H., & Grant, M. (2006). A health map for the local human habitat. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 126(6), 252–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424006070466

- Bay-Richter, C., Träskman-Bendz, L., Grahn, P., & Brundin, L. (2012). Garden rehabilitation stabilises INF-gamma and IL-2 levels but does not relieve depressive-symptoms. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 18(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2012.02.002

- Brown, B., Dybdal, L., Noonan, C., Pedersen, M. G., Parker, M., & Corcoran, M. (2020). Group gardening in a Native American Community: A collaborative approach. Health Promotion Practice, 21(4), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919830930

- Buck, D. (2016). Gardens and health implications for policy and practice. The Kings Fund.

- Cases, M. G., Fruge, A. D., De Los Santos, J. F., Locher, J. L., Cantor, A. B., Smith, K. P., Glover, T. A., Cohen, H. J., Daniel, M., Morrow, C. D., Moellering, D. R., & Demark-Wahnefried, W. (2016). Detailed methods of two home-based vegetable gardening intervention trials to improve diet, physical activity, and quality of life in two different populations of cancer survivors. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 50, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2016.08.014

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2008). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews in health care. University of York.

- Chan, H. Y., Ho, R. C., Mahendran, R., Ng, K. S., Tam, W. W., Rawtaer, I., Tan, C. H., Larbi, A., Feng, L., Sia, A., Ng, M., Gan, G. L., & Kua, E. H. (2017). Effects of horticultural therapy on elderly’ health: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0588-z

- Cipriani, J., Benz, A., Holmgren, A., Kinter, D., Mcgarry, J., & Rufino, G. (2017). A systematic review of the effects of horticultural therapy on persons with mental health conditions. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2016.1231602

- Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J., & Camic, P. (2013). Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(4), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-02-2013-0007

- Corazon, S. S., Stigsdotter, U. K., Jensen, A. G., & Nilsson, K. (2010). Development of the nature-based therapy concept for patients with stress-related illness at the Danish healing forest garden Nacadia. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 20, 34–51.

- Corazon, S. S., Nyed, P. K., Sidenius, U., Poulsen, D. V., & Stigsdotter, U. K. (2018). A long-term follow-up of the efficacy of nature-based therapy for adults suffering from stress-related illnesses on levels of healthcare consumption and sick-leave absence: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010137

- Dean, J., Van Dooren, K., & Weinstein, P. (2011). Does biodiversity improve mental health in urban settings? Medical Hypotheses, 76(6), 877–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.02.040

- Demark-Wahnefried, W., Cases, M. G., Cantor, A. B., Fruge, A. D., Smith, K. P., Locher, J., Cohen, H. J., Tsuruta, Y., Daniel, M., Kala, R., & De Los Santos, J. F. (2018). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a home vegetable gardening intervention among older cancer survivors shows feasibility, satisfaction, and promise in improving vegetable and fruit consumption, reassurance of worth, and the trajectory of central adiposity. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 118(4), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.11.001

- Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. (2018). A green future: Our 25-year plan to improve the environment. UK Government.

- Detweiler, M. B., Self, J. A., Lane, S., Spencer, L., Lutgens, B., Kim, D.-Y., Halling, M. H., Rudder, T. F., & Lehmann, L. (2015). Horticultural therapy: A pilot study on modulating cortisol levels and indices of substance craving, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and quality of life in veterans. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 21(4), 36–41.

- Harris, H. (2017). The social dimensions of therapeutic horticulture. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(4), 1328–1336. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12433

- Hartig, T. (2004). Restorative environments. In Spielberger, C., (Ed). Encyclopedia of applied psychology. Academic Press. pp. 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-657410-3/00821-7

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

- Harvest for Health in Older Cancer Survivors (2016). Identification number NCT02985411. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02985411

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savovic, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343(7829), d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Howarth, M., Brettle, A., Hardman, M., & Maden, M. (2020). What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: A scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open, 10(7), e036923. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036923

- Huang, W. Z., Liu, L., Wang, Z. J., Mai, G. H., Cui, A. Y., & Yan, W. (2018). Effect of horticultural therapy on psychological factors of patients with hand functional rehabilitation. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, 122(2), 50.

- Kam, M. C. Y., & Siu, A. M. H. (2010). Evaluation of a horticultural activity programme for persons with psychiatric illness. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(2), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1861(11)70007-9

- Kamioka, H., Tsutani, K., Yamada, M., Park, H., Okuizumi, H., Honda, T., Okada, S., Park, S.-J., Kitayuguchi, J., Abe, T., Handa, S., & Mutoh, Y. (2014). Effectiveness of horticultural therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 22(5), 930–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2014.08.009

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kim, K. H., & Park, S. A. (2018). Horticultural therapy program for middle-aged women’s depression, anxiety, and self-identify. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 39, 154–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.06.008

- Kotozaki, Y. (2013a). Comparison of the effects of individual and group horticulture interventions. Health Care: Current Reviews, 02(02). https://doi.org/10.4172/hccr.1000120

- Kotozaki, Y. (2013b). The Psychological changes of horticultural therapy intervention for elderly women of earthquake related areas. Journal of Trauma & Treatment, 3(1).

- Kotozaki, Y. (2014a). Horticultural therapy as a measure for recovery support of regional community in the disaster area: A preliminary experiment for forty five women who living certain region in the coastal area of Miyagi Prefecture. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 16(2), 112–116.

- Kotozaki, Y. (2014b). The psychological effect of horticultural therapy intervention of earthquake related stress in women of earthquake related areas. Journal of Translational Medicine & Epidemiology, 2(1)

- Litt, J. S., Alaimo, K., Buchenau, M., Villalobos, A., Glueck, D. H., Crume, T., Fahnestock, L., Hamman, R. F., Hebert, J. R., Hurley, T. G., Leiferman, J., & Li, K. (2018). Rationale and design for the community activation for prevention study (CAPs): A randomized controlled trial of community gardening. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 68, 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2018.03.005

- Makizako, H., Tsutsumimoto, K., Doi, T., Hotta, R., Nakakubo, S., Liu-Ambrose, T., & Shimada, H. (2015). Effects of exercise and horticultural intervention on the brain and mental health in older adults with depressive symptoms and memory problems: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial [UMIN000018547]. Trials, 16(1), 499. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1032-3

- Makizako, H., Tsutsumimoto, K., Doi, T., Makino, K., Nakakubo, S., Liu-Ambrose, T., & Shimada, H. (2019). Exercise and horticultural programs for older adults with depressive symptoms and memory problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010099

- McGuinness, L. A., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2021). Risk-of-bias Visualization (Robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1411

- McKenzie, J. E., Brennan, S. E (2021). Chapter 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., Welch, V. A., (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane.

- Nacadia Effect Study (NEST) (2013). Identification number NCT01849718. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01849718

- Ng, K. S. T., Chan, H. Y., Sia, A., Mahendran, R., Tan, H. C., Feng, L., Ng, M. K.-W., Tan, C. T. Y., Larbi, A., Ho, R. C.-M., & Kua, E. H. (2016). The effects of horticultural therapy on the psychological well-being and associated biomarkers of elderly in Singapore. Alzheimers and Dementia, 12(7), 1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.117

- Ng, K., Sia, A., Ng, M., Tan, C., Chan, H., Tan, C., Rawtaer, I., Feng, L., Mahendran, R., Larbi, A., Kua, E. H., & Ho, R. (2018). Effects of horticultural therapy on Asian older adults: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1705–1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081705

- Ng, K. S. T., Sia, A., Ng, M. K.-W., Kua, E., & Ho, R. C.-M. (2019). Horticultural therapy improves IL-6 and social connectedness differentially. Alzheimers and Dementia, 15(7), P1211–P1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.3649

- Nicholas, S. O., Giang, A. T., & Yap, P. L. K. (2019). The effectiveness of horticultural therapy on older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(10), 1351.e1–1351.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.021

- Odeh, R., & Guy, C. (2018). Gardening and art study: Assessing biometric changes for healthy women in a randomized. Controlled Intervention. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, 131, 224–227.

- Okvat, H. (2011). A pilot study of the benefits of traditional and mindful community gardening for urban older adults’ subjective well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University] ASU Digital Repository. https://repository.asu.edu/

- Pálsdóttir, A. M., Andersson, G., Grahn, P., Norrving, B., Kyrö-Wissler, S., Petersson, I. F., & Pessah-Rasmussen, H. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of nature-based post-stroke fatigue rehabilitation ("the nature stroke study" (NASTRU)): study design and progress report Paper presented at the ESO, Glasgow.

- Pálsdóttir, A. M., Stigmar, K., Grahn1, P., Norrving, B., & Pessah-Rasmussen, H. (2016). The Nature Stroke Study (NASTRU), Nature-based rehabilitation of post stroke fatigue- A randomised controlled trial. Paper presented at the 2nd European Stroke Organisation Conference 2016.

- Pálsdóttir, A., Stigmar, K., Norrving, B., Grahn, P., Petersson, I., Åström, M., & Pessah-Rasmussen, H. (2020). The nature stroke study; NASTRU: A randomized controlled trial of nature-based post-stroke fatigue rehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 52(2), jrm00020. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2652

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. (2020). Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration,

- Sempik, J. (2010). Green care and mental health: Gardening and farming as health and social care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 14(3), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.5042/mhsi.2010.0440

- Sempik, J., Hine, R., & Wilcox, D. (2010). (Eds) Green care: a conceptual framework: a report of the working group on the health benefits of green care, COST Action 866, Green Care in Agriculture, Loughborough: Loughborough University, Centre for Child and Family Research. From: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254841074_Green_Care_a_Conceptual_Framework_A_Report_of_the_Working_Group_on_the_Health_Benefits_of_Green_Care

- Sidenius, U., Karlsson Nyed, P., Linn Lygum, V., & Stigsdotter, U. K. (2017). A diagnostic post-occupancy evaluation of the Nacadia(R) therapy garden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080882

- Siu, A. M. H., Kam, M., & Mok, I. (2020). Horticultural therapy program for people with mental illness: A mixed-method evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 711–710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030711

- Soga, M., Gaston, K. J., & Yamaura, Y. (2017). Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports, 5, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.007

- Sterne, J. A., Gavaghan, D., & Egger, M. (2000). Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: Power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(11), 1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00242-0

- Spano, G., Giannico, V., Elia, M., Bosco, A., Lafortezza, R., & Sanesi, G. (2020a). Human health-environment interaction science: An emerging research paradigm. The Science of the Total Environment, 704, 135358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135358

- Spano, G., D’Este, M., Giannico, V., Carrus, G., Elia, M., Lafortezza, R., Panno, A., & Sanesi, G. (2020b). Are community gardening and horticultural interventions beneficial for psychosocial wellbeing? A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103584

- Stigsdotter, U. K., Corazon, S. S., Sidenius, U., Karlsson Nyed, P., Larsen, H. B., & Fjorback, L. O. (2018). Efficacy of nature-based therapy for individuals with stress-related illnesses: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 213(1), 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.2

- The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Med, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Thompson, R. (2018). Gardening for health: A regular dose of gardening, Clinical Medicine. Clinical Medicine, 18(3), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.18-3-201

- Thomson, L. J., Camic, P. M., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2015). Social prescribing: A review of community referral schemes. University College London.

- Ulrich, R. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

- Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

- Vujcic, M., Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J., Grbic, M., Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., & Toskovic, O. (2017). Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environmental Research, 158, 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.030

- Vujcic, M., Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J., Tosevski, D. L., Vukovic, O., & Toskovic, O. (2021). Development of evidence-based rehabilitation practice in botanical garden for people with mental health disorders. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 14(4), 242-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867211007941

- Wang, D., & MacMillan, T. (2013). The benefits of gardening for older adults: A systematic review of the literature. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 37(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2013.784942

- Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

- Yeo, N. L., Elliott, L. R., Bethel, A., White, M. P., Dean, S. G., & Garside, R. (2020). Indoor nature interventions for health and wellbeing of older adults in residential settings: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 60(3), e184–e199. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz019