Abstract

Background

Recovery Colleges (RCs) are education-based centres providing information, networking, and skills development for managing mental health, well-being, and daily living. A central principle is co-creation involving people with lived experience of mental health/illness and/or addictions (MHA). Identified gaps are RCs evaluations and information about whether such evaluations are co-created.

Aims

We describe a co-created scoping review of how RCs are evaluated in the published and grey literature. Also assessed were: the frameworks, designs, and analyses used; the themes/outcomes reported; the trustworthiness of the evidence; and whether the evaluations are co-created.

Methods

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology with one important modification: “Consultation” was re-conceptualised as “co-creator engagement” and was the first, foundational step rather than the last, optional one.

Results

Seventy-nine percent of the 43 included evaluations were peer-reviewed, 21% grey literature. These evaluations represented 33 RCs located in the UK (58%), Australia (15%), Canada (9%), Ireland (9%), the USA (6%), and Italy (3%).

Conclusion

Our findings depict a developing field that is exploring a mix of evaluative approaches. However, few evaluations appeared to be co-created. Although most studies referenced co-design/co-production, few described how much or how meaningfully people with lived experience were involved in the evaluation.

Introduction

Personal recovery in mental health and addictions (MHA) is defined as living a purposeful, meaningful life despite the presence of mental distress (Slade, Citation2010). While recovery-oriented practices existed in European healthcare settings as early as 200 years ago, their appearance in North America at the national policy level did not occur until the late 1980s in the U.S. (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Citation2004) and the early 2000s in Canada (Kirby & Keon, Citation2006). This introduction was due to persistent consumer/survivor/ex-patient advocacy (Morrow & Weisser, Citation2012) and epidemiological evidence that substantial symptom reduction could occur in mental illnesses previously thought to be “incurable” (Harding & Zahniser, Citation1994).

The key conceptual shift introduced by recovery is that the focus is the individual not the symptoms. The concept of recovery “…involves making sense of, and finding meaning in, what has happened; becoming an expert in your own self-care; building a new sense of self and purpose in life; discovering your own resourcefulness and possibilities and using these, and the resources available to you, to pursue your aspirations and goals” (Perkins et al., Citation2012, p. 2). In this context, social inclusion can be a significant goal for many people working toward recovery (Mental Health Commission of Canada, Citation2015).

However, despite decades of efforts to incorporate a recovery approach into the mental health care system, people with lived experience of mental health/illness and/or addictions (MHA) continue to confront inequitable social inclusion, including high rates of un- and under-employment and low rates of educational achievement (Whitley et al., Citation2019). In response, recovery colleges (RCs) were developed and first implemented in 2009 in the United Kingdom. They have since been established in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan, and the United States (Perkins et al., Citation2018). Drawing on educational theories such as transformative and constructivist learning (Hoban, Citation2015), RCs provide education and skills development courses to help manage and navigate daily living.

A critical principle is that RCs are co-created by people with lived experience of MHA and people with other forms of relevant expertise (e.g. mental health professionals, administrators, and researchers). Co-creation encompasses a wide range of activities including co-design, co-production, collaborative implementation, and mutual decision-making and planning. It can be defined as multiple stakeholders with various perspectives and areas of expertise, including lived experience, collaboratively identifying gaps and subsequently producing, developing, implementing, and evaluating programs (Brandsen et al., Citation2018). Co-created programming produces a culture of equity and inclusion where everyone’s assets, strengths, resources, and networks are celebrated and leveraged in pursuit of a common goal (Lewis et al., Citation2017). Co-creation allows for the right to self-determination and choice to be exercised by all stakeholders. It is thus central to providing those with lived experiences the opportunity to gain skills, confidence, hope, and resilience through the shift from “patient” to “student.” By re-centering the voices of lived experience, the diverse nature of consumer needs and understandings of neurodiversity become visible (Happell et al., Citation2003).

There is promising evidence that RCs increase positive recovery outcomes such as connection, hope, meaning, and empowerment (Thériault et al., Citation2020). However, researchers also note the need for more evaluation. A recent systematized search found almost no robust evaluative research on how RCs work and what outcomes they produce (Toney et al., Citation2018). This is a significant concern given the rapid global expansion of RCs.

There are complexities to developing evaluation measures for RCs. A fundamental issue is the complex nature of recovery that encompasses one’s attitude, values, feelings and goals (Mead et al., Citation2000). As such, recovery and the intended impacts of RCs include both objectively measurable (e.g. re-hospitalization, employment, return to school) and subjectively defined outcomes (e.g. increased confidence, improved resilience).

Our response is to conduct a scoping review to map out what work has been reported and identify important knowledge gaps (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This would serve as a first step for establishing an evaluation framework and designing corresponding methodologies, data collection, and analysis tools. However, given the centrality of co-creation to all aspects of RCs, it is crucial that this principle is also applied within the context of a meaningful and rigorous review.

Our purpose is to describe the process and results of a co-created scoping review designed to answer the question: How have RCs been evaluated in the published and grey literature?

This review is part of a larger grant that aims to combine the review results with qualitative research findings to identify recovery-oriented processes and outcomes that matter most to RC participants and use this information to co-create how RC evaluation measures will be selected (Lin et al., Citation2022).

Method

Overview

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) methodology with one important modification. “Consultation,” originally an optional last stage, became our first, foundational step. We re-conceptualized this as “co-creator engagement.” The purpose was to ensure that RC student/facilitator participation was integrated throughout the review process.

The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to ensure our process and results met the current standards for reporting on knowledge synthesis research (Tricco et al., Citation2018). Covidence, a systematic review management software program, was used to import citations, screen titles and abstracts, upload references, and for data abstraction (https://www.covidence.org/).

Step 1: Co-creator engagement

Although we describe co-creator engagement as a “step,” it was imbedded throughout the scoping review. To ensure the inclusion of the RC student/facilitator perspective, individuals with the relevant experiences were recruited and eventually constituted two-thirds of the team. To create a common knowledge base, education sessions were a standing agenda item, with the sessions addressing the voiced needs of the team members. Topics included presentations by team members on their own lived experiences with mental health challenges; introductions to scoping review methods, evaluation, qualitative research, epistemology and ontology; the philosophy and history of RCs; and a walkthrough of a complex analytic publication by a researcher team member.

Processes were established to address the power differentials inherent in co-production teams. Every meeting began with a “check-in” where members were encouraged to share what had happened in their lives since the previous meeting. The purpose of this style of communication is to establish that all are valuable contributors with lives outside of the project, equalize power relations across the different roles and types of expertise, and provide unique perspectives to the team. Sharing personal daily experiences and individual challenges creates a culture of trust essential to fostering reciprocity and mutual respect (Peters et al., Citation2013).

As the team developed, we added a recorded “check-out” at the end of each meeting. The purposes were to share reflections on how the meeting went and generate a potential database on co-production processes. A structure was also developed so that members uncomfortable with any aspect of the meetings were encouraged to consider the options of raising them to the group or discussing them privately with either the team or project leaders.

The team routinely revisited issues such as whether the scoping review questions and search terms were adequate; whether the data abstraction plans and templates needed revision; and how the results should be analyzed, interpreted, and communicated.

Step 2: Identifying the research question

Our research question was: how have RCs been evaluated in the published and grey literature?

Related questions included what theoretical frameworks, approaches, and designs were chosen; how trustworthy was the evidence provided; what kind of impact did the evaluations have; and, most importantly, how were people with lived experience involved in the evaluation?

Step 3: Identifying relevant studies

The librarian (TR) designed a comprehensive search strategy based on consultation with the team. A preliminary sample of abstracts were test-reviewed and used to refine the strategy. To identity relevant scholarly literature, TR then translated and executed the finalized strategy in the following bibliographic databases: Medline, Embase, APA PsycInfo, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), and the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS). A “wide angle” approach was used to ensure broad coverage and include all relevant disciplines and articles regardless of study design or article type (Levac et al., Citation2010). Publication year limits were from the date of each database’s inception to 18–19 January 2021. No language limits were applied. (See full search strategy, Supplementary Material A.) In addition, national and international RC networks were consulted and reference lists of review articles handsearched to ensure that evaluation studies were not missed. Each database search was rerun on 17 March 2022 to capture articles published in the 14 months since the original searches were conducted.

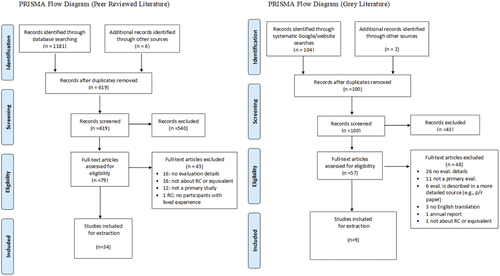

To identify relevant grey literature, team experts and national and international RC networks were consulted to develop a list of known RCs and recovery-oriented organizations around the world. TR handsearched each program or organization’s website to locate evaluation reports, feedback materials, or documents that included robust metrics. TR also conducted multiple Google searches using keywords such as “recovery college” AND “evaluation” and advanced search operators (e.g. filetype:pdf) to identify any additional relevant documents. All identified materials were presented to the team in an Excel spreadsheet in preparation for screening. During the location of the full texts associated with this initial list, a further two grey literature documents were found and added to screening. shows the PRISMA-ScR flowcharts for our peer-reviewed and grey literature searches.

Stage 4: Study selection

A two-step selection process was performed. First, titles and abstracts were screened; then full-text screening followed for those articles or reports that met criteria. The team discussed potential inclusion and exclusion criteria which were then applied to a random selection of four articles and four reports. Team discussions led to modifications of the criteria and refinement of the team’s understanding of what these criteria meant. These discussions continued until the team was satisfied with both the criteria and the screening process.

Five inclusion and one exclusion criteria were chosen (). Criterion 2 was identified as especially complex and difficult to apply. The team discussed extensively questions such as “how do we know they are a ‘real’ Recovery College as opposed to an organization that simply uses the label?” or “what characteristics should they have before they count as a true Recovery College?” Since RC fidelity guidelines are neither mandated nor universally accepted and since it was not within our scope to dictate a definition, we opted to include all studies that assessed an organization that either called itself a Recovery College or whose main focus was clearly educational rather than therapeutic.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for abstract screening template.

Each screening step was performed by two independent reviewers. General concerns about how to apply the criteria were discussed and resolved in the group’s weekly meetings. For reviewer differences regarding specific article/reports, a designated team member who was not a screener (SS) made the consensus decision.

Step 5: Charting the data

The 43 articles and reports that passed the screening process then underwent full abstraction. The development, piloting, and modification of the abstraction template followed the same method used for the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A draft template was co-created and piloted on two peer-reviewed articles and one grey literature report and then discussed and modified by the team. Each article or report was abstracted by two independent reviewers with general concerns about how to apply the template discussed and resolved by the group and specific differences between reviewers resolved by a third team member (SS) who did not perform any abstractions.

The final abstraction template covered two main domains: descriptive and evaluation information. (For the full template, see Supplementary Material B.)

Descriptive information included the RC’s name, its geographic location, the year it was founded, and who was eligible to attend. The team also judged whether any aspect of the RC or the evaluation itself was co-produced or co-created. “Co-production” and “co-creation,” like the definition used for “Recovery College,” were liberally defined. Essentially, any mentions of words such as “co-create,” “co-produce,” “co-facilitate,” or “co-design” were coded as “yes” while the absence of such words was coded as “information not provided.” If abstractors were unsure, they used an “uncertain” code. For all “yes” and “uncertain” codes, the abstractors were provided supporting information from the study in the template.

Information about the evaluation included what theory or framework was used, whether qualitative or quantitative approaches were taken, the study and analysis design, and what outcomes were measured or themes identified. In keeping with Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), we did not assess study quality. However, we felt that addressing the “trustworthiness” of the results was important. Consequently, for qualitative studies, we noted whether the authors described processes supporting the credibility of the results or reflection by the evaluators. For quantitative studies, we recorded whether conflict of interest statements or evidence of instrument reliability or validity was provided. Also, for quantitative evaluations, we noted whether influences other than RC attendance were considered – for example, analyzing covariates or control/comparison groups. Finally, we were interested in any reported impacts or consequences of the evaluation.

Step 6: Collating and summarizing the results

Pairs of team members collated and summarized the abstraction results for the descriptive information, evaluation frameworks, and co-production/co-design sections while the lead author (EL) reviewed all of these summaries. Occasionally, the original articles or reports were re-examined to verify that the important details had been correctly captured. These summaries were then integrated into a complete final draft by the lead author (EL) and then reviewed, discussed, and modified by the full team.

Results

Descriptive information ()

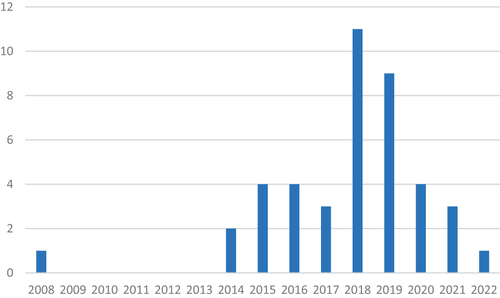

Of the 43 evaluations we reviewed, 34 (79%) were peer-reviewed, and nine (21%) were grey literature. These latter included six reports (Anglia Ruskin University, Citation2014; Barton & Williams, Citation2015; Kaminskiy & Moore, Citation2015; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Taylor et al., Citation2017; Wels, Citation2016), one PowerPoint presentation (Arbour et al., Citation2019), one conference poster (Mayo Recovery College, Citationn.d.), and one white paper (Canadian Mental Association Calgary, Citation2020). The earliest evaluation in our search was published in 2008, with numbers beginning to increase in 2014 and reaching a peak in 2018 and 2019 (). The numbers decreased by a half to two-thirds in 2020 and 2021.

Table 2. Descriptive information of RCs provided in peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Because some RCs were evaluated more than once, these 43 papers and reports represented 33 individual RCs. The majority were from the UK (19, 58%), followed by Australia (5, 15%), Canada and Ireland (3 RCs each, 9% each), the USA (2, 6%), and Italy (1, 3%). Additionally, one evaluation surveyed multiple countries (King & Meddings, Citation2019). The majority of the individual RCs were initiated between 2013 and 2016 (23, 70%) with one beginning in 2012 (Frayn et al., Citation2016), two in 2017 (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2019), and the remaining seven providing no information (Burhouse et al., Citation2015; Canadian Mental Association Calgary, Citation2020; Dunn et al., Citation2008; Harper & McKeown, Citation2018; Newman-Taylor et al., Citation2016; Peer et al., Citation2018; Windsor et al., Citation2017).

Twenty-six RCs (79%) used the label “Recovery College.” The remaining seven used a variety of terms including “Recovery Academy,” “Recovery Education Center,” “Recovery Education Project,” “Recovery Center,” “Discovery College,” or “Discovery Centre.”

Involving people with lived experience, since it was an inclusion criterion, was endorsed by all of the RCs represented in . Nineteen RCs also described other groups who were eligible to attend. The most commonly mentioned were family members (100% of the 19 RCs), health and other professionals (17, 89%), and the public (7, 37%).

Table 3. Evaluation information provided in peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Table 4. Co-production information provided in peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Evaluation frameworks ()

The definition of “evaluation framework” varies but can be conceptualized as “both a planning process and written product” that guides the conduct of evaluation (Markiewicz & Patrick, Citation2016, p. 1). Based on this definition, we identified 14 evaluations (33%) as using a framework.

Four employed frameworks that they identified as rooted in RC principles. Taylor et al. (Citation2017) used the CHIME (Connectedness, Hope and Optimism, Identity, Meaning, Empowerment) framework (Leamy et al., Citation2011) while three studies were steered by ImROC guidance on quality and outcomes assessment for RCs (Shepherd et al., Citation2014). Ebrahim et al. (Citation2018) drew on a framework, designed in partnership with ImROC, covering six areas of evaluation: quality of recovery-supporting care, achievement of recovery goals, subjective measures of personal recovery, achievement of socially valued goals, quality of life, and service use. Sommer et al. (Citation2019) adopted a framework based on the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS)—an instrument and process outlined in the ImROC guidance (Kiresuk & Sherman, Citation1968). Kaminskiy and Moore (Citation2015) used a 4-part evaluation framework informed by Moore’s process evaluation of complex interventions (Citation2015) and the ImROC practice guidelines for choosing outcome domains.

Although not specifically informed by RC frameworks, two further papers noted that their evaluation was based on recovery concepts. Cameron et al. (Citation2018) drew from social learning theory within the context of developing communities of practice (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2014), and Critchley et al. (Citation2019) used the BASIC Ph Model of resilience (Lahad et al., Citation2013) in their evaluation of their RC’s dramatherapy program.

Three papers (Durbin et al., Citation2021; Khan et al., Citation2020; Reid et al., Citation2019), evaluating the same RC, used realist evaluation to develop a mixed-methods quasi-experimental design to assess the impact of RC participation on individuals with mental health challenges who had also experienced homelessness (Durbin et al., Citation2021). Another evaluation (Thompson et al., Citation2021) used the Framework Method (Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003) to guide an inductive qualitative evaluation.

Finally, four evaluations used “bespoke” frameworks – that is, ones that they developed for their own purposes. This included one framework for evaluating financial and social return on investment (Barton & Williams, Citation2015) and one based on the principles of recovery (Peer et al., Citation2018). Two other evaluations described collaborative mixed-methods frameworks. Hall et al. (Citation2018) used a co-produced design comprised of document review, interviews, surveys, and focus groups while Kenny et al. (Citation2020) conducted a cross-sectional evaluation of outcomes experienced by RC members.

What evaluation approaches and designs were chosen?

There were 33 evaluations that used qualitative methods and 31 that used quantitative methods. Nearly half used both (49%, 16 peer-reviewed, 5 grey literature). Twenty-eight percent used qualitative methods only (11 peer-reviewed, 1 grey literature), and 23% used quantitative methods only (eight peer-reviewed, two grey literature). Two other evaluations included student quotations illustrating their quantitative findings but gave no description of how these were obtained (Canadian Mental Association Calgary, Citation2020; Critchley et al., Citation2019).

Sample size, data sources, data analysis

Sample sizes varied widely between four (Harper & McKeown, Citation2018) and 781 participants (Peer et al., Citation2018). While the qualitative evaluations tended to have smaller numbers, some analyzed open-ended questions embedded in quantitative surveys resulting in larger than usual qualitative samples (e.g. 89 students, Ebrahim et al., Citation2018).

For the 33 qualitative studies, the most common data sources were free-text information gathered from answers to open-ended survey questions, course feedback comments, or other forms of written communication such as solicited anonymous letters (48%, 12 peer-review, 4 grey literature). One-on-one interviews and focus groups were the next most common (45% and 39%, respectively). Only two studies used group interviews (Kaminskiy & Moore, Citation2015; Newman-Taylor et al., Citation2016). Thirty-six percent used two or more qualitative data collection methods.

The qualitative studies largely used thematic analysis (23 studies, 70%) with only one using grounded theory (Hopkins et al., Citation2018). Four used additional analytic methods. Hall et al. (Citation2018) used their bespoke evaluation framework in addition to thematic analysis for their 1-on-1 interviews and focus groups and content analysis for their secondary analysis of RC documents. Stevens et al. (Citation2018) used Fisher’s exact test, a quantitative method, to examine the relationship between themes identified from a qualitative interview and subsequent self-reported improvement. Thompson et al. (Citation2021) used the Framework Method (Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003) to support their thematic analysis, and Wilson et al. (Citation2019) grouped responses to free-text answers to survey questions although methodological details were not provided.

Data sources for the 31 quantitative studies included administrative/archival databases, student surveys, and course feedback forms. Twenty-nine percent analyzed administrative or archival data such as student registration information, linked health service records, or financial/cost data while 71% conducted RC student surveys. Thirteen percent used course feedback information, and 19% used two or more of these sources of data.

Sixty-one percent (15 peer-reviewed, 4 grey literature) used a pre-post design. Of these, three (Dunn et al., Citation2008; Durbin et al., Citation2021; Sommer et al., Citation2019) also measured at least one additional time point (e.g. 1 year later).

In analyzing quantitative data, 48% (nine peer-reviewed, six grey literature) reported descriptive statistics only such as frequencies, unweighted percentages, or means. Forty-five percent (12 peer-reviewed, 2 grey literature) evaluated whether the differences they found were statistically meaningful using tests such as the Wilcoxon signed, Fisher’s exact, or paired-sample t-test. Four of these studies also controlled for covariates via multivariate modeling techniques (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Dunn et al., Citation2008; Durbin et al., Citation2021; Sommer et al., Citation2019), and three studies (Dunn et al., Citation2008; Durbin et al., Citation2021; Peer et al., Citation2018) included comparison groups.

Themes, outcomes

The purposes for which the evaluations were done fell roughly into three categories: to explore or evaluate impacts at the system-level, the RC or course-level, or the individual student level. Of the 43 evaluations, 26% (eight peer-reviewed, three grey literature) covered more than one category.

Ten evaluations (23%) gathered information about system-level outcomes with the most common being health care use and costs. Pre-post changes for RC students were examined by five studies using linked administrative health or financial data (Barton & Williams, Citation2015; Bourne et al., Citation2018; Cronin et al., Citation2021; Kay & Edgley, Citation2019; Sutton et al., Citation2019). Wels (Citation2016) also evaluated the RC’s performance against the standards defined in their health system service level agreement.

Three studies considered impacts outside of health care. Sutton et al. (Citation2019) also considered the impact of attending RC courses on employment status, primary income source, and job seeking behaviour. Hall et al. (Citation2018) reported qualitative findings that some students became involved in RC volunteer or paid positions. Finally, Meddings et al. (Citation2019) used census information to evaluate access by comparing diversity of the RC student body to that of the local community.

Not surprisingly, the majority of the 43 studies (28, 65%) focused on the RC/course level. Sixteen used primarily qualitative methods to explore aspects of RC development or implementation including facilitators and barriers, course design processes, and RC adherence to recovery principles (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Frayn et al., Citation2016; Hall et al., Citation2018; Harper & McKeown, Citation2018; Hopkins et al., Citation2022; Hopkins et al., Citation2018; Hopkins et al., Citation2018; Kaminskiy & Moore, Citation2015; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Khan et al., Citation2020; King & Meddings, Citation2019; Lucchi et al., Citation2018; Meddings et al., Citation2014; Peer et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2019; Windsor et al., Citation2017). Some of the themes found in these studies included the shift from treatment to education, the value of co-facilitation, the utility of lived experiences of mental ill-health, redressing power imbalances, and social inclusion.

Twenty (47%) examined the impact of RC attendance particularly related to specific courses (Anglia Ruskin University, Citation2014; Arbour et al., Citation2019; Burhouse et al., Citation2015; Critchley et al., Citation2019; Dunn et al., Citation2008; Durbin et al., Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2018; Frayn et al., Citation2016; Hall et al., Citation2018; Hopkins et al., Citation2022; Hopkins et al., Citation2018; Kaminskiy & Moore, Citation2015; Kay & Edgley, Citation2019; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Meddings et al., Citation2015; Nurser et al., Citation2017; Sommer et al., Citation2019; Stevens et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2019; Windsor et al., Citation2017). The majority of these studies used quantitative methods to describe cross-sectional results or assess pre-post changes. The most commonly measured outcomes were satisfaction (10 studies); well-being (6 studies); and recovery, gains in knowledge and skills, and achievement of the student’s learning goals (5 studies each). There were 28 standardized instruments used in these quantitative studies (see end of ), but no universally adopted ones. The most frequently administered were the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) which measures well-being and psychological distress (Tennant et al., Citation2007) and the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) (Neil et al., Citation2009).

Some of these studies also included qualitative components which yielded a number of themes including many of the themes described above as well as personal transformation, increased motivation and recovery management skills, and a sense of hope and purpose.

Finally, 16 evaluations (37%) used qualitative methods to further elicit student perceptions and experiences. In addition to the themes reported by the RC/course-level studies, students mentioned topics such as the RC as a transformational space (Muir-Cochrane et al., Citation2019), appreciating the value of education (Anglia Ruskin University, Citation2014), addressing their own fears (Kenny et al., Citation2020), and the opportunity to widen their horizons (Newman-Taylor et al., Citation2016).

How trustworthy was the evidence provided?

While quality assessment of these studies was out-of-scope, we did abstract several characteristics related to the trustworthiness of the evaluation results. For qualitative studies, we noted whether the authors mentioned reflexivity or strategies to address credibility, two important processes in qualitative research to identify influences or biases in the results (Santiago-Delefosse et al., Citation2016). For quantitative studies, we noted where potential biases might be introduced by not considering non-RC factors, not disclosing conflict of interest, or not considering instrument reliability and validity.

Only one qualitative evaluation described reflection by the authors (Stevens et al., Citation2018) while 12 of the 33 studies (36%) mentioned strategies supporting credibility. For the quantitative studies, as described earlier, the potential influence of non-RC factors was addressed by five studies through including covariates (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Sommer et al., Citation2019), comparison groups (Dunn et al., Citation2008; Peer et al., Citation2018), or both (Durbin et al., Citation2021). Two quantitative studies included conflict-of-interest statements in the body of their publications (Bourne et al., Citation2018; Durbin et al., Citation2021) although others likely included them in journal sections not retrieved by our search process. Finally, 14 of the 31 quantitative studies either specifically mentioned the reliability and/or validity of their survey instruments or chose established questionnaires.

What kind of impact did the evaluations have?

Only four RCs (12%) reported consequences resulting from their evaluations. Impact on courses was reported by three studies in terms of modifying course duration and order (Cameron et al., Citation2018), refining curriculum committee processes (Hall et al., Citation2018), or improving registration (Arbour et al., Citation2019). Another RC used their evaluation results to improve their outreach efforts, particularly for underrepresented groups (Meddings et al., Citation2019), to change the RC’s training methods and governance, and to create processes that would support routine outcome measurement (Meddings et al., Citation2014). Finally, one RC reported using their results to support funding applications as well as to establish external partnerships (Hall et al., Citation2018).

How were people with lived experience involved? ()

Because of the importance of co-production and co-design in RCs, it is not surprising that the majority of the 43 evaluations (79% overall; 76% peer-reviewed, 89% grey literature) described some aspect of their RCs using terms such as “co-produced,” “co-developed,” “co-designed,” or “co-facilitated.”

However, only six studies (14%) provided specific information describing co-development or co-production of their evaluations with two describing fairly extensive processes. Hall et al. (Citation2018) note their “deliberate strategy to ensure that the perspectives of people with lived experience was [sic] invited and valued through all aspects of the project” (p. 10). This included involving people with lived experience in the co-design and implementation of the evaluation framework, methods, and data collection materials and having them participate in a focus group to digest and distill the results. The study by Thompson et al. (Citation2021) recruited and hired a previous RC student to serve as a Lived Experience Advisor. This individual helped shape their evaluation approach, developed and pilot-tested the data collection materials, and co-authored the publication.

Three other studies also reported the participation of people with lived experience in the research process or the evaluation working group. Meddings et al. (Citation2015) noted that all methodological decisions were co-produced via consultation with both students and peer trainers as well as mental health professionals. In the study by Bourne et al. (Citation2018), all stages were reviewed and discussed in monthly meetings with RC students, trainers, managers, researchers, and service providers. Harper and McKeown (Citation2018) also described collaboration between a working group of former students with the research team in developing both broad and specific aspects of the evaluation.

Finally, Zabel et al. (Citation2016) used an semi-structured interview guide that they described as collaboratively created.

The remaining evaluations either provided no (32, 74%) or limited information (5, 12%). For example, no mention was made of stakeholder collaboration, input, or consultation (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Stevens et al., Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2019). One study (Durbin et al., Citation2021) mentioned service user input but provided no details, and another (Taylor et al., Citation2017) reported using an evaluation approach that had been co-created elsewhere but not how the decision was made to adopt it.

Summary and discussion

The literature covered by this scoping review demonstrates a growing appreciation of the need for evaluation in RCs. The number of publications and reports almost quadrupled between 2017 and 2018/2019. There was a recent decrease in 2020 and 2021 possibly due to the impact of the global pandemic.

One-third used a theoretical framework. These frameworks tended to be recovery-based (e.g. CHIME, ImROC) rather than using traditional evaluation approaches such as Kirkpatrick (Citation1994) or Moore et al. (Citation2009). Almost half used both qualitative and quantitative methods, reflecting a combination of intentions to both explore and assess. Within these methods, a number of studies (36% for qualitative studies, 19% for quantitative studies) used more than one data-gathering method. Several evaluations took advantage of already gathered, secondary data (e.g. open-ended questions from quantitative surveys, administrative health data), either alone or together with primary data. For quantitative evaluations that assessed RC/course-level impact, almost half provided descriptive statistics only. However, a promising 45% tested for meaningful pre-post differences with a few using more complex multivariate or comparison group analyses to account for non-RC influences.

These 43 studies investigated a variety of outcomes or experiences at the system, RC/course, and student levels. Over one-quarter examined at least two levels. System-level evaluations focussed primarily on health care and related costs although a few studies included wider impacts such as volunteering, paid employment, and participation in further education. RC/course-level evaluations focused on both implementation processes and pre-post student outcomes. At the student-level, the results yielded information on the personal impact of attending RCs and of the underlying principles of inclusion and co-development that the RCs embodied.

Our findings depict a field that is developing, growing, and consequently exploring a mix of evaluative approaches. However, we also identified a number of areas that would benefit from further consideration.

The most striking is the small number of evaluations (14%) that appeared to be co-developed or co-produced. As a pillar of the RC model, co-production should be a guiding principle for all RC activities. While nearly every study referenced recovery and co-design/co-production in their introductions and descriptions of their RC, many did not provide clear information about how these principles were applied to their evaluations. In particular, very few described how much or how meaningfully people with lived experience were involved. There may be many explanations for this scarcity of information including that it was provided elsewhere (e.g. an internal report) or that the contributing individuals chose not to disclose their personal histories in published form. However, co-production is such a central principle that our review suggests that this is a sizeable information gap in the published literature that deserves considerably greater attention.

The second point is that the variety of study approaches, consistent with the developmental nature of RC evaluation, encompasses a mix of top-down and bottom-up methods. There is an inherent tension between the use of standardized tools and more individualized approaches that measure success by the individual’s own goals. The use of standardized tools is often consistent with the expectations and even requirements of external accountability audiences such as government ministries or funding agencies (Shepherd et al., Citation2014). The perceived advantage is that such tools allow us to compare and/or combine data with other RCs using the same instruments. Comparing or creating opportunities for larger sample sizes can generate information about gaps or strengths beyond the individual RC doing the evaluation. On the other hand, evaluations geared towards measuring success as defined by an individual’s own goals are better for creating a more complete picture of the human experience. These client-centered methods can provide in-depth information about the experience and impact of the individual RC on its participants, which is the driving value in recovery. In addition, evaluations that are for participants are more likely to be meaningful to RC participants and others with lived experience (Bloom, Citation2010).

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses, and the variability in the studies we reviewed suggests that RCs are very much aware of them. We propose that the choice of which approach or mix of approaches should be tailored to the RC’s purpose (e.g. comparability with other RCs, in-depth exploration of their own students). Regardless of the purpose, our results suggest two important considerations. First, procedures establishing the trustworthiness of the evaluation results should be described. Second, as mentioned earlier, there should be close attention to how individuals with lived experience are actively and meaningfully involved in the evaluation. In particular, clearer descriptions of whether and how co-creation was used to choose methods, analyze findings, and prepare the final manuscript are critical even if they are worded broadly (e.g. individuals with lived experiences were actively involved vs. person XX was an individual with lived experience) to respect individual preferences about disclosing their backgrounds.

Finally, as the field develops, more attention is needed toward synthesizing findings, either via theoretical frameworks or by integrating quantitative and qualitative analytic methods. For example, Stevens et al. (Citation2018) used a creative combination of quantitative and qualitative tools to evaluate an RC arts course. They conducted a pattern-matching analysis where they used Fisher’s exact test to determine whether the presence of certain themes identified at a 3-month follow-up interview were associated with being categorized as having improved wellbeing three or six months later. They synthesized these findings with pre-post test scores from standardized instruments, deductive qualitative analyses of post-course focus groups with facilitators, and written student feedback. In this way, they sought to balance the tension across evaluation priorities to provide a nuanced exploration of program outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

As with all scoping reviews, this project is not without limitations. The lack of a universally accepted definition of Recovery College and associated fidelity criteria means that there is variability in how this term is used. Consequently, we chose to broadly include studies using “Recovery College” or an equivalent term indicating that education was the main approach to supporting or improving recovery for students. An additional limitation is that only English-language literature was reviewed. Future directions should address scholarship presented in different languages. Also, due to limited resources, we were unable to update our grey literature search in 2022; therefore, grey literature published after January 2021 was not included.

Nonetheless, this project offers a significant and unique contribution to the scholarship landscape. To our knowledge, this is the first peer-reviewed publication examining the methods and outcomes used to evaluate Recovery Colleges. This report also offers unique insight into the ways in which the methods and outcomes are chosen. Given that co-design is central to the Recovery College model, an important future direction would be to engage various stakeholders to co-design an evaluation strategy for Recovery Colleges that is relevant and impactful to students.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (127.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The support and contributions of Sanjeev Sockalingam are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anglia Ruskin University. (2014). Evaluation of the mid Essex Recovery College, October – December 2013. https://arro.anglia.ac.uk/id/eprint/347125/

- Arbour, S., Stevens, A., & Gasparini, J. (2019). Recovery College: Influencing recovery-related outcomes. Culture and System Transformation.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Barton, S., & Williams, R. (2015). Evaluation of “the exchange” (Barnsley Recovery College). https://rfact.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Evaluation-of-The-Exchange-Barnsley-Recovery-College-SWYFT.pdf

- Bloom, M. (2010). Client-centered evaluation: Ethics for 21st century practitioners. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 7(1), 7. http://secure.ce-credit.com/articles/101748/3bloom.pdf

- Borkin, J., Steffen, J., Ensfield, L., Krzton, K., Wishnick, H., & Yangarger, N. (2000). Recovery attitudes questionnaire: Development and evaluation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24(2), 95–102.

- Bourne, P., Meddings, S., & Whittington, A. (2018). An evaluation of service use outcomes in a Recovery College. Journal of Mental Health, 27(4), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417557

- Boyd, J. E., Otilingam, P. E., & DeForge, B. R. (2014). Brief version of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to depression, self esteem, recovery orientation, empowerment, and perceived devaluation and discrimination. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 37(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000035

- Brandsen, T., Steen, T., & Vershuere, B. (Eds.). (2018). Co-production and co-creation: Engaging citizens in public services (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315204956

- Burhouse, A., Rowland, M., Marie Niman, H., Abraham, D., Collins, E., Matthews, H., Denney, J., & Ryland, H. (2015). Coaching for recovery: A quality improvement project in mental healthcare. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports, 4(1), u206576.w2641. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u206576.w2641

- Cameron, J., Hart, A., Brooker, S., Neale, P., & Reardon, M. (2018). Collaboration in the design and delivery of a mental health Recovery College course: Experiences of students and tutors. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(4), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466038

- Canadian Mental Health Association. (2020). Recovery College: White paper. Canadian Mental Health Association.

- Chisholm, D., Knapp, M. R., Knudsen, H. C., Amaddeo, F., Gaite, L., & Van Wijngaarden, B. (2000). Client socio-demographic and service receipt inventory – European Version: development of an instrument for international research – EPSILON Study 5. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(S39), s28–s33. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.39.s28

- Critchley, A., Dokter, D., Odell-Miller, H., Power, N., & Sandford, S. (2019). Starting from Scratch: Co-production with dramatherapy in a Recovery College. Dramatherapy, 40(2), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263067219843442

- Cronin, P., Stein-Parbury, J., Sommer, J., & Gill, K. H. (2021). What about value for money? A cost benefit analysis of the South Eastern Sydney Recovery and Wellbeing College. Journal of Mental Health, 0(0), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1922625

- Davies, W. (2011). Manhattan Recovery Measure.

- Derogatis, L. R., & Lazarus, L. (1994). SCL-90-R, Brief Symptom Inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M. E. Mariush (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment (pp. 217–248). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dinnis, S., Roberts, G., Hubbard, C., Hounsell, J., & Webb, R. (2007). User-led assessment of a recovery service using DREEM. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31(4), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.106.010025

- Dunn, E. C., Rogers, E. S., Hutchinson, D. S., Lyass, A., MacDonald Wilson, K. L., Wallace, L. R., & Furlong-Norman, K. (2008). Results of an innovative university-based recovery education program for adults with psychiatric disabilities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(5), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0176-9

- Durbin, A., Nisenbaum, R., Wang, R., Hwang, S. W., Kozloff, N., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2021). Recovery education for adults transitioning from homelessness: A longitudinal outcome evaluation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 763396. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.763396

- Ebrahim, S., Glascott, A., Mayer, H., & Gair, E. (2018). Recovery Colleges: How effective are they? The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 13(4), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2017-0056

- Eisen, S. V., Dill, D. L., & Grob, M. C. (1994). Reliability and validity of a brief patient report instrument for psychiatric outcome education. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 45(3), 242–247.

- Ensfield, L., Steffen, J., & Borkin, J. (1999). Personal vision of recovery questionnaire: The development of a consumer-driven scale. University of Cincinnati.

- EuroQol Office. (n.d.). EQ-5D-5L – EQ-5D. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/

- Fitts, W. H., & Warren, m W. L. (1996). Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services.

- Frayn, E., Duke, J., Smith, H., Wayne, P., & Roberts, G. (2016). A voyage of discovery: Setting up a recovery college in a secure setting. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 20(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-06-2015-0025

- Greenwood, K. E., Sweeney, A., Williams, S., Garety, P., Kuipers, E., Scott, J., & Peters, E. (2010). CHoice of Outcome In Cbt for psychosEs (CHOICE). Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(1), 126–135.

- Hall, T., Jordan, H., Reifels, L., Belmore, S., Hardy, D., Thompson, H., & Brophy, L. (2018). A process and intermediate outcomes evaluation of an Australian Recovery College. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 1(3), 7–20. papers3://publication/uuid/93E2A4F5-3590-45F1-85FE-14A4CA7CDD1B

- Happell, B., Pinikahana, J., & Roper, C. (2003). Changing attitudes: The role of a consumer academic in the education of postgraduate psychiatric nursing students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 17(2), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1053/apnu.2003.00008

- Harding, C. M., & Zahniser, J. H. (1994). Empirical correction of seven myths about schizophrenia with implications for treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(s384), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05903.x

- Harper, L., & McKeown, M. (2018). Why make the effort? Exploring recovery college engagement. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-10-2017-0043

- Hibbard, J. S., Stockard, J., Mahoney, E. R., & Tusler, M. (2004). Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Services Research, 39(4 Pt 1), 1005–1026.

- Hoban, D. (2015). Developing a sound theoretical educational framework [Paper presentation]. Recovery Colleges: International Community of Practice. Proceedings of June 2015 Meeting (pp. 8–13). Recovery Colleges Internaitonal COmunity of Practice (RCICoP).

- Hopkins, L., Foster, A., Belmore, S., Anderson, S., & Wiseman, D. (2022). Recovery colleges in mental health-care services: An Australian feasibility and acceptability study. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 26(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-06-2021-0035

- Hopkins, L., Foster, A., & Nikitin, L. (2018). The process of establishing Discovery College in Melbourne. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(4), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-07-2018-0023

- Hopkins, L., Pedwell, G., & Lee, S. (2018). Educational outcomes of Discovery College participation for young people. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-07-2018-0024

- Kaminskiy, E., & Moore, S. (2015). South Essex Recovery College evaluation project report (pp. 1–53). https://arro.anglia.ac.uk/id/eprint/600456

- Kay, K., & Edgley, G. (2019). Evaluation of a new recovery college: Delivering health outcomes and cost efficiencies via an educational approach. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 23(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-10-2018-0035

- Kenny, B., Kavanagh, E., McSherry, H., Brady, G., Kelly, J., MacGabhann, L., Griffin, M., Farrelly, M., Kelly, N., Ross, P., Barron, R., Watters, R., & Keating, S. (2020). Informing and transforming communities, shaping the way forward for mental health recovery. Dublin North. North East Recovery College.

- Khan, B. M., Reid, N., Brown, R., Kozloff, N., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2020). Engaging adults experiencing homelessness in recovery education: A qualitative analysis of individual and program level enabling factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 779. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00779

- King, T., & Meddings, S. (2019). Survey identifying commonality across international Recovery Colleges. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 23(3), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-02-2019-0008

- Kirby, M. J. L., & Keon, W. (2006). Out of the shadows at last: Transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada (highlights and recommendations). https://sencanada.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/391/soci/rep/pdf/rep02may06high-e.pdf

- Kiresuk, T. J., & Sherman, R. E. (1968). Goal attainment scaling: A general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(6), 443–453. 10.1007/BF01530764

- Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1994). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler; Publishers Group West.

- Lahad, M., Schacham, M., & Ayalon, O. (Eds.). (2013). The ‘BASIC Ph’ model of coping and resilience: Theory, research and cross-cultural application. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Lehman, A. F., Postrado, L. T., Roth, D., McNary, S. W., & Goldman, H. H. (1994). Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program on chronic mental illness. The Milbank Quarterly, 72(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350340

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lewis, A., King, T., Herbert, L., & Repper, J. (2017). Co-production – Sharing our experiences, reflecting on our learning. http://imroc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ImROC-co-pro-briefing-FINAL-4.pdf

- Lin, E., Harris, H., Gruszecki, S., Costa-Dookhan, K. A., Rodak, T., Sockalingam, S., & Soklaridis, S. (2022). Developing an evaluation framework for assessing the impact of Recovery Colleges: protocol for a participatory stakeholder engagement process and co-created scoping review. BMJ Open.

- Lucchi, F., Chiaf, E., Placentino, A., & Scarsato, G. (2018). Programma FOR: A recovery college in Italy. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 1(3), 29–37.

- Markiewicz, A., & Patrick, I. (2016). Developing monitoring and evaluation frameworks. Sage Publications.

- Mayo Recovery College. (n.d.). My words, my way. Mayo Recovery College.

- Mead, S., Copeland, M. E., & Lehman, A. F. (2000). What recovery means to us: consumer’s perspective. Community Mental Health Journal, 36(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1001917516869

- Meddings, S., Campbell, E., Guglietti, S., Lambe, H., Locks, L., Byrne, D., & Whittington, A. (2015). From service user to student: The benefits of recovery college. Clinical Psychology Forum, 2015(268), 32–37.

- Meddings, S., Guglietti, S., Lambe, H., & Byrne, D. (2014). Student perspectives: Recovery college experience. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 18(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-05-2014-0016

- Meddings, S., Walsh, L., Patmore, L., McKenzie, K. L. E., & Holmes, S. (2019). To what extent does Sussex Recovery College reflect its community? An equalities and diversity audit. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 23(3), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-04-2019-0011

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2015). Guidelines for recovery-oriented practice: Hope. dignity. Inclusion. Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- Moore, D. E. J., Green, J. S., & Gallis, H. A. (2009). Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 29(1), 1–15.

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O'Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 350, h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmh.h1258

- Morrow, M., & Weisser, J. (2012). Towards a social justice framework of mental health recovery. Studies in Social Justice, 6(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v6i1.1067

- Muir-Cochrane, E., Lawn, S., Coveney, J., Zabeen, S., Kortman, B., & Oster, C. (2019). Recovery college as a transition space in the journey towards recovery: An Australian qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 21(4), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12637

- Neil, S. T., Kilbride, M., Pitt, L., Nothard, S., Welford, W., Sellwood, W., & Morrison, A. P. (2009). The questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR): A measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis, 1(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522430902913450

- Newman-Taylor, K., Stone, N., Valentine, P., Sault, K., & Hooks, Z. (2016). The Recovery College: A unique service approach and qualitative evaluation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(2), 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000179

- Nurser, K., Hunt, D., & Bartlett, T. (2017). Do recovery college courses help to improve recovery outcomes and reduce self-stigma for individuals who attend? Clinical Psychology Forum, 300, 32–37.

- Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136319

- Peer, J. E., Gardner, M., Autrey, S., Calmes, C., & Goldberg, R. W. (2018). Feasibility of implementing a recovery education center in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(2), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000295

- Perkins, R., Meddings, S., Williams, S., & Repper, J. (2018). Recovery Colleges 10 years on. www.cnwl.nhs.uk/recoveryCollege

- Perkins, R., Repper, J., Rinaldi, M., & Brown, H. (2012). 1. Recovery Colleges. https://imroc.org/resources/1-recovery-colleges/

- Peters, D. H., Adam, T., Alonge, O., Agyepong, I. A., & Tran, N. (2013). Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. British Journal of Medicine, 347(v20), f6753. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6753

- Reid, N., Castel, S., Veldhuizen, S., Roberts, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2019). Effect of a psychiatric emergency department expansion on acute mental health and addiction service use trends in a large urban center. Psychiatric Services, 70(11), 1053–1056. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900112

- Ridgway, P., & Press, A. (2004). Assessing the recovery-orientation of your mental health program: A user’s guide for the recovery-enhancing environment scale (REE). Version 1. https://recoverycontextinventory.com/images/resources/A_users_guide_for_developing_DREEM.pdf

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications.

- Rogers, E. S., Chamberlin, J., Ellison, M. S., & Crean, T. (1997). A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 48(8), 1042–1047.

- Santiago-Delefosse, M., Gavin, A., Bruchez, C., Roux, P., & Stephen, S. L. (2016). Quality of qualitative research in the health sciences: analysis of the common criteria present in 58 assessment guidelines by expert users. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 148, 142–151.

- Secker, J., Hacking, S., Kent, L., Shenton, J., & Spandler, H. (2009). Development of a measure of social inclusion for arts and mental health project participants. Journal of Mental Health, 18(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701677803

- Shepherd, G., Boardman, J., & Rinaldi, M. (2014). Supporting recovery quality and outcomes briefing (pp. 1–34). Centre for Mental Health and Mental Health Network. http://www.nhsconfed.org/-/media/Confederation/Files/public-access/Supporting-recovery-quality-and-outcomes-briefing.pdf

- Shepherd, G., Boardman, J., Rinaldi, M., & Roberts, G. (2014). Supporting recovery in mental health services: Quality and outcomes. Briefing Paper No. 8. UK.

- Slade, M. (2010). Mental illness and well-being: The central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 10(26), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-26

- Sommer, J., Gill, K. H., Stein-Parbury, J., Cronin, P., & Katsifis, V. (2019). The role of recovery colleges in supporting personal goal achievement. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(4), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000373

- Sommer, J., Gill, K., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2018). Walking side-by-side: Recovery Colleges revolutionising mental health care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-11-2017-0050

- Stevens, J., Butterfield, C., Whittington, A., & Holttum, S. (2018). Evaluation of arts based courses within a UK recovery college for people with mental health challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061170

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2004). National consensus statement on mental health recovery. SAMHSA.

- Sutton, R., Lawrence, K., Zabel, E., & French, P. (2019). Recovery College influences upon service users: A Recovery Academy exploration of employment and service use. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 14(3), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-06-2018-0038

- Taylor, D., Boland, A., & Wallace, N. (2017). Mid West ARIES project: A report on the development, progress and outcomes of a pilot project to provide a recovery education service in the Mid West. University of Limerick.

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7252-5-63

- Thériault, J., Lord, M. M., Briand, C., Piat, M., & Meddings, S. (2020). Recovery Colleges after a decade of research: A literature review. Psychiatric Services, 71(9), 928–940. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.PS.201900352

- Thompson, H., Simonds, L., Barr, S., & Meddings, S. (2021). Recovery colleges: Long-term impact and mechanisms of change. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 25(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-01-2021-0002

- Toney, R., Elton, D., Munday, E., Hamill, K., Crowther, A., Meddings, S., Taylor, A., Henderson, C., Jennings, H., Waring, J., Pollock, K., Bates, P., & Slade, M. (2018). Mechanisms of action and outcomes for students in recovery colleges. Psychiatric Services, 69(12), 1222–1229. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800283

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850/SUPPL_FILE/M18-0850_SUPPLEMENT.PDF

- Tsemberis, S., McHugo, G., Williams, V., Hanrahan, P., & Stefancic, A. (2007). Measuring homelessness and residential stability: The residential time-line followback inventory. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(1), 29–42. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20132

- Uttaro, T., & Lehman, A. (1999). Graded response modeling of the quality of life interview. Evaluation and Program Planning, 22(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(98)00039-1

- Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Bayliss, M. S., McHorney, C. A., Rogers, W. H., & Raczek, A. (1995). Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the medical outcomes study. Medical Care, 33(4), AS264–AS279.

- Ware, J., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. (1995). SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales (2nd ed.). The Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

- Wels, J. (2016). Recovery College Greenwich – Evaluation report. https://www.bridgesupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Enc-4.1-Greenwich-University-Evaluation-Report-August-2016-Final.pdf

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2014). Learning in a landscape of practice: A framework. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton-O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, & B. Wenger-Trayner (Eds.), Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning (pp. 13–29). Routledge.

- Whitley, R., Shepherd, G., Slade, M., Whitley, R., Shepherd, G., & Slade, M. (2019). Recovery colleges as a mental health innovation. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20620

- Williams, J., Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Norton, S., Pesola, F., & Slade, M. (2015). Development and evaluation of the INSPIRE measure of staff support for personal recovery. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(5), 777–786.

- Wilson, C., King, M., & Russell, J. (2019). A mixed-methods evaluation of a Recovery College in South East Essex for people with mental health difficulties. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1353–1362. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12774

- Windsor, L., Roberts, G., & Dieppe, P. (2017). Recovery Colleges – Safe, stimulating and empowering. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(5), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-06-2017-0028

- Zabel, E., Donegan, G., Lawrence, K., & French, P. (2016). Exploring the impact of the recovery academy: A qualitative study of Recovery College experiences. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(3), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-12-2015-0052