Abstract

Background

Environmental adversity and subclinical symptoms of psychopathology in adolescents increase their risk for developing a future psychiatric disorder, yet interventions that may prevent poor outcomes in these vulnerable adolescents are not widely available.

Aims

To develop and test the feasibility and acceptability of a prevention-focused program to enhance resilience in high-risk adolescents.

Method

Adolescents with subclinical psychopathology living in a predominantly low-income, Latinx immigrant community were identified during pediatrician visits. A group-based intervention focused on teaching emotion recognition and regulation skills was piloted in three cohorts of adolescents (n = 11, 10, and 7, respectively), using a single arm design. The second and third iterations included sessions with parents.

Results

Eighty-eight percent of participants completed the program, which was rated as beneficial. Also, from baseline to end of treatment, there was a significant decrease in subclinical symptoms and a significant increase in the adolescents’ positive social attribution bias (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

A resilience-focused intervention administered to high-risk adolescents was found to be feasible and acceptable to participants. Future work is needed to determine whether such a program can reduce the incidence of negative outcomes, such as the development of psychiatric disorders and related disability, in this population.

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of heightened vulnerability for the development of psychiatric disorders. Preceding the onset of a full syndromal psychiatric illness, many adolescents experience subsyndromal or subthreshold symptoms for variable amounts of time. Consistent with this, it has been well-established that subthreshold symptoms are associated with elevated risk for the development of future psychiatric illnesses (Hofstra et al., Citation2002), including psychotic (Hanssen et al., Citation2005; Poulton et al., Citation2000) and mood disorders (Carpenter et al., Citation2022; Kelleher, Keeley, et al., Citation2012; Uchida et al., Citation2017). Moreover, adolescents with subthreshold symptoms often experience significant distress (Kelleher et al., Citation2012), suicidality (Kelleher, Keeley, et al., Citation2012) and lower social functioning (Balázs et al., Citation2013; Rai et al., Citation2010) compared to their peers without subthreshold symptoms. Psychosocial interventions designed to target subthreshold symptoms in adolescents could delay or prevent the onset of psychiatric illness (Addington et al., Citation2019; Dozois et al., Citation2009). However, few programs implementing such an approach have been validated or studied in community settings.

Because many common risk factors have been identified across a range of psychiatric illnesses, including genetic risk, trauma, early psychiatric symptoms, and environmental factors (Mandelli et al., Citation2015; Stilo et al., Citation2017; van Os & Reininghaus, Citation2016), a “transdiagnostic” prevention approach, which relies on the identification of adolescents with risk factors that are shared across psychiatric conditions, may be more effective than focusing on preventing a single category of illness (McGorry et al., Citation2018; Shah et al., Citation2020). Many subthreshold symptoms of psychiatric illness (such as subclinical negative affect, anxiety, and mild psychotic symptoms) represent transdiagnostic risk factors, as these symptoms are associated with risk for developing multiple psychiatric illnesses (van Os & Reininghaus, Citation2016).

Based on this literature, we designed a group-based behavioral intervention for adolescents that focuses on teaching emotion recognition skills and strategies for managing distressing thoughts and emotions that have been effective in previous studies (Hollon et al., Citation2002; Horowitz & Garber, Citation2006; Thompson et al., Citation2015). We then delivered this intervention to middle school-aged adolescents with two risk factors for developing psychiatric disorders: (1) subclinical symptoms of psychopathology, and (2) living in a community in which high levels of adversity are commonly experienced.

This community was based in a town in Massachusetts with relatively high rates of poverty (18% of residents are under the federal poverty line), substance misuse, violence, and low educational attainment, compared to elsewhere in the state (Massachusetts General Hospital & Center for Community Health Improvement, Citation2012; Patrick et al., Citation2007; U.S. Census Bureau, Citationn.d.). More than half of this community’s residents are first-generation immigrants and 67% identify as Hispanic or Latinx (U.S. Census Bureau, Citationn.d.).

Adolescents with ethnically diverse backgrounds and non-English speaking families are less likely to receive psychiatric treatment (Rickwood et al., Citation2007), are poorly represented in intervention trials (Hollon et al., Citation2002), and at higher risk for developing psychiatric illness (Liang et al., Citation2016). Thus, the adolescents living in this community have multiple risk factors for developing psychiatric conditions and are unlikely to receive mental health services in a timely manner, suggesting that a brief, low burden, prevention-focused intervention could be beneficial to them.

Therefore, we designed and piloted a group-based intervention for these at-risk adolescents focused on teaching emotion recognition and emotion regulation skills. The primary outcomes assessed in this pilot study were acceptability and feasibility of the program. We also hypothesized that the intervention would be associated with reductions in subthreshold symptoms, less negative affect, and improved social functioning, assessed in secondary, exploratory analyses.

In addition, we tested a hypothesized mechanism of the intervention, related to emotion recognition skills. We focused on emotion recognition in the intervention because performance on measures of emotion recognition, which is an initial step in emotion regulation (Wiggins et al., Citation2016), has been shown to predict social functioning in adults and children (McLaughlin et al., Citation2011; Osborne et al., Citation2017). Moreover, certain types of “errors” or biases in emotion recognition have been linked to psychopathology or resilience-promoting capacities. Biases towards labeling emotionally neutral stimuli as negatively-valenced has been associated with negative affect and symptoms of psychopathology (Leppänen et al., Citation2004; Pinkham et al., Citation2011; Yoon & Zinbarg, Citation2008), whereas a bias towards labeling neutral stimuli as positively-valenced has been associated with positive affect and optimism (Beadel et al., Citation2016). Psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapies aim to modify such biases, and this bias modification is thought to represent an underlying mechanism that accounts for these interventions’ positive effects on mental health (Reiter et al., Citation2021). Thus, based on this well-known model, we also explored whether the intervention altered emotion recognition biases.

Methods

Study design

Adolescents were screened for eligibility during visits to their pediatrician at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Chelsea Healthcare Center Department of Pediatrics. Parents/caregivers (referred to simply as “parents” below for the sake of brevity) of adolescents with elevated scores on the self-report screening measure (see details below) were told that their child may be eligible for a research study evaluating a group-based intervention that teaches techniques for managing stress, interacting effectively with others, and managing difficult emotions. Families received $10 gift cards for participating in each session of the program and $30 gift cards for participating in baseline and post-intervention assessments.

The study was approved by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Partners Healthcare IRB (protocol 2018P002421). Parents provided consent, and children provided assent prior to the initiation of any study procedures. Parent consent was completed in their preferred language (English or Spanish) by bilingual research staff.

Program cohorts

The intervention was piloted in three cohorts of adolescents, Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 (n = 11, 10, and 7, respectively). For Cohorts 1 and 2, the intervention was delivered in-person. For Cohort 3, the intervention was delivered virtually via Zoom due to restrictions on in-person meetings related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants and recruitment

Screening

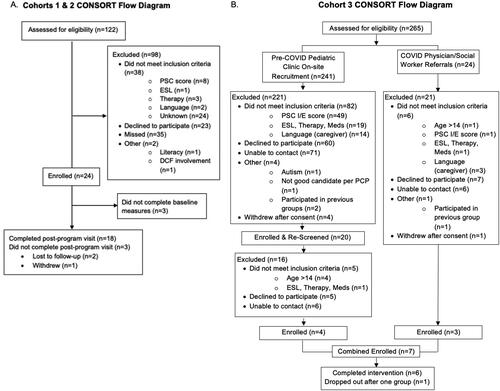

For all cohorts, a bilingual clinical research coordinator was present in the MGH Chelsea Healthcare Center. To minimize burden for participants and providers, screening for the study relied on screening instruments already being collected in the pediatrics clinic as a part of annual well child pediatrician visits. Potentially eligible youth and their parents were approached in person before or after their appointment or via telephone after the visit (see , CONSORT diagram).

Adolescents in Cohort 1 completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Citation2001) in English. The SDQ includes five subscales: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. All subscales except the prosocial subscale were summed to calculate a “total difficulties” score. Adolescents were deemed eligible if their scores were equal to or exceeded the “high normal” cut-off for one or more of the SDQ subscales or for the SDQ total difficulties scale.

In 2019, the Pediatrics Department of the MGH Chelsea Healthcare Center chose to no longer administer the SDQ and changed their behavioral health screening instrument to the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC; Jellinek et al., Citation1988). Thus the PSC was used for screening Cohorts 2 and 3 of this study. Given the known lower sensitivity of the PSC in Latinx populations (Jutte et al., Citation2003), a score of ≥1 on either the internalizing or externalizing symptoms subscale of the PSC was used as the eligibility cut-off for this scale.

For Cohort 3, adolescents were initially screened for the intervention 10 months prior to its start, due to delays related to the COVID-19 pandemic and were rescreened immediately prior to the baseline evaluation (see ). Potentially eligible adolescents were also referred to study staff by their pediatrician and/or social work and were screened by phone.

Eligibility

Eligibility requirements for the adolescent participants in all three cohorts were: (1) age of 11–14 years, (2) proficiency in English, and (3) subclinical psychiatric symptoms as reflected by an elevated score on the screening instrument. Exclusion criteria included: a referral by the adolescent’s pediatrician for a psychiatric assessment or any behavioral health treatment, any history of psychotropic medication use (except for stimulant medications), current psychological or psychiatric treatment, unstable medical illness, developmental delay, or an urgent need for mental health care. For Cohorts 2 and 3, because the parent sessions were conducted in Spanish, the child was eligible if they met the above criteria and their participating parent/caregiver was proficient in Spanish. For Cohort 3, adolescents and parents were also required to have a smartphone or computer with internet access to participate. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of Chelsea Public Schools provided laptop computers and internet access to all students, so this requirement did not represent a significant barrier to participation.

Assessments

Overview

In Cohorts 1 and 2, in-person assessments were conducted at baseline and post-intervention. Assessments included satisfaction surveys (see below), the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL; Achenbach, Citation2009) and an emotion recognition task (Wiggins et al., Citation2017). In Cohorts 1 and 2, 18 adolescents and their parents completed the post-intervention visit (85.7% completion rate). Two adolescents did not complete the baseline emotion recognition task, and two adolescents did not complete the post-intervention emotion recognition task. For Cohort 3 (virtual), only feasibility and acceptability were assessed. Adolescent measures were completed in English and parent measures were collected in the parent’s preferred language (English or Spanish).

Feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility data included percentage of eligible participants who enrolled and group attendance. For all cohorts, acceptability was measured by an adolescent satisfaction survey. For Cohorts 2 and 3, parents completed a quantitative parent satisfaction survey and a qualitative feedback form. Responses on the acceptability questionnaires ranged from 0 to 4 (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) and included questions assessing engagement and comfort during the sessions and what they learned (see Supplemental Figure 1).

Parent-report of symptoms

Parents completed the parent-report CBCL for ages 6–18 (Achenbach, Citation2009), which is comprised of five subscales: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Social Problems, Somatic Complaints, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior (Ebesutani et al., Citation2010). Given the focus of the intervention on emotional regulation/negative affect reduction and related social functioning skills, we examined the Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Social Problems subscales as secondary outcomes. Subscale scores were converted to age and gender-normed T-scores which range from 50-100.

Emotion recognition task (i.e., facial emotion labeling)

Adolescents completed a computerized facial emotion labeling task adapted from the task of Wiggins and colleagues (Wiggins et al., Citation2016). The stimuli used in the task were images from the Pictures of Facial Affect set (Ekman & Friesen, Citation1976) of angry, fearful, and happy faces that had been digitally combined with neutral faces to create faces with varying intensities of each emotion category: 0%, 50%, 75%, and 100% intensity. Participants were presented with eight trials of each of the four levels of emotional intensity (0, 50, 75, 100%) per emotion (angry, fearful, happy) resulting in 96 trials (the task was shortened relative to the original version to decrease participant burden). The stimuli were presented in a random order for a duration of two seconds each. During stimulus presentation, participants were instructed to identify the emotion (angry, fearful, happy, neutral) that the face expressed as quickly as possible.

Iterative design and content of the intervention

Overview of intervention design

The intervention aimed to improve emotion recognition skills, promote communication about emotions, and teach adaptive ways of responding to difficult experiences and emotions. All sessions were co-led by two licensed masters or doctoral-level clinicians, one of whom was bicultural and bilingual (fluent in English and Spanish).

Adolescents in Cohort 1 completed a ten-session intervention. Based on observations of this cohort and evidence that psychoeducation of parents and parent training can positively impact the mental health of adolescents (Martinez & Eddy, Citation2005; Smith, Citation2004), two parent-only sessions were added and the youth-only component was delivered in 8 sessions (to maintain the same total number of sessions) for Cohort 2. Because these two parent-only sessions were experienced as beneficial by parents (see ), one youth-parent combined session was then added to the program, for Cohort 3, to allow for modeling of discussions between parents and youth about emotion recognition and adaptive ways of responding to emotional distress.

Intervention content

Adolescent sessions: Group agreements with participants were discussed in the first session of the intervention to establish ground rules, and ice-breaker activities were used to identify commonalities among participants. Each session included a mindfulness practice (e.g., breathing, mindful eating), and additional experiential exercises were also woven into each session, to allow participants to practice the skills with support. Home practice assignments then allowed them to consolidate and generalize the skills learned during the session to their home environment.

Activities related to learning emotion recognition skills included: instruction in emotion self-monitoring, “emotion detective” exercises, instruction in the thought-feeling-behavior behavioral model of specific emotions (e.g., commonly associated thoughts, somatic sensations, body language, facial expressions), and vignettes depicting interpersonal interactions that trigger emotional reactions as a stimulus for learning about how to recognize the emotional states of others (i.e., mentalization).

Parent sessions: The material for parents similarly focused on emotion recognition, and the purpose of emotions. Specifically, the parent sessions focused on teaching parents emotion regulation skills and prompting their children to use these skills based on the Social Regulatory Cycle (SRC) framework (Reeck et al., Citation2016). The SRC proposes that parents, as “emotion regulators”, can intervene to strengthen their adolescents’ emotion regulation skills. The regulator functions to (1) accurately identify the adolescent’s emotional state; (2) assess if there is a need for emotion regulation; (3) select an emotion regulation strategy; and (4) implement this strategy. According to this model, the adolescent will act in parallel to (1) identify the situational trigger and their own emotional state; (2) decide how to direct their attention; (3) appraise the situation; and (4) decide how to respond behaviorally. By teaching emotion regulation skills to parents, the SRC framework emphasizes the ways that parents can help children identify a need for emotion regulation and respond appropriately.

Also, group leaders discussed with parents that certain reactions to their children’s experience may not be helpful, such as responding to negative emotional states by invalidating, minimizing, or punishing a child’s expression of negative emotions. Discussions of adaptive ways of responding emphasized cognitive response modulation skills, such as emotional acceptance, attentional shifting, and cognitive reappraisal. Mindfulness, or awareness of the current moment, including the non-judgmental acceptance of emotions (Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990), was taught as a method of exerting positive effects on mental health, via increases in emotion recognition and emotional acceptance (vs. suppression/avoidance). In addition, techniques that promoted self- and other-compassion were taught as an alternative to emotional suppression, self-blame, and self-criticism in response to difficult emotions (Neff, Citation2003).

Along with their children, parents were also assigned emotion tracking and recognition exercises for home practice that would allow them to integrate the skills learned in the sessions into their daily lives and to facilitate communication about emotional experiences within their families.

Lastly, during the parent sessions and throughout the program, the group leaders strove to adhere to values important in Latinx culture, such as personalismo (friendliness and ability to relate), familismo (an appreciation of the central role of family, including extended family), and respeto (providing space for participants to share their stories).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 24. Differences among the cohorts were first examined using t-tests and chi square analyses.

Symptoms

CBCL scores on the Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Social Problems subscales were converted to T-scores based on normative data and were analyzed using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Facial emotion labeling

We tested for changes in the rates of misattribution of negative or positive affect to neutral faces (i.e., mislabeling neutral faces as angry/fearful or happy) using paired-samples t-tests. We also explored whether the intervention impacted overall accuracy of labeling emotional faces, using a repeated measures ANOVA on number of correct trials, with time (baseline/post-intervention) and emotional valence as factors, as well as emotional intensity.

Results

Participants

Participant characteristics (across the three cohorts) are shown in . The cohorts differed only on reported race, with Cohort 1 reporting significantly more “other” race than the other two cohorts (overall χ2=14.9, p = 0.005; Cohort 1 versus Cohort 2: χ2 = 6.5, p = 0.04; Cohort 1 versus Cohort 3: χ2 = 9.2, p = 0.01). Participants were predominantly male (59%, n = 16) and had a mean age of 12.4 (SD = 1.1) years. Virtually all participants identified as Hispanic (96%, n = 26). Most parents had not completed high school (57.2%), and Spanish was the most common primary language spoken at home (82% of families).

Table 1. Adolescent participant characteristics (n = 28).

Feasibility

Across the three cohorts, a total of 387 participants were screened. Of those, 104 (27%) were eligible and 32 (31% of those eligible) consented to participate. Four withdrew after the consenting process, resulting in a total of 28 participants (11 in Cohort 1, 10 in Cohort 2, and seven in Cohort 3; ).

Due to a data storage error, attendance information was not available for Cohort 1. Adolescent participants of Cohort 2 attended 93% of the sessions on average (7.44 ± 0.73/8 total), and Cohort 2 parents attended 100% of the two parent sessions. Adolescent participants of Cohort 3 attended 88% of the sessions on average (6.50 ± 0.84/8 total) and parent participants of Cohort 3 attended an average of 72% of the parent sessions (2.17 ± 0.75/3 total).

Acceptability

Following the program, both the adolescents and parents were asked questions about how useful, interesting, and helpful the sessions were, their level of comfort during the program, whether they would recommend the program, and the degree to which they applied the concepts and tools they were taught during their daily lives. In addition, the adolescents were asked about effects of the program on their confidence, self-efficacy and self-knowledge, and the parents were asked whether the program taught them new ways to communicate with their child and new approaches for helping their child manage their emotions.

Overall, the ratings revealed that the adolescents and parents were generally satisfied with the intervention (see for examples of parent feedback comments and Supplemental Figure 1 for the mean adolescent and parent satisfaction scores for each item).

Table 2. Qualitative data – parent feedback (cohorts 2 and 3).

For example, for Cohorts 1 and 2, most adolescents agreed or strongly agreed that the program taught them how to better manage “when things go wrong” (mean rating ± SD: 2.6 ± 0.9), that the program was interesting (mean rating ± SD: 2.6 ± 0.8), and that “this group has helped me communicate better with others” (mean ± SD: 2.6 ± 0.9). In Cohort 2, the parents agreed or strongly agreed that the program taught them “new information about emotions and why they are important” (mean ± SD: 3.4 ± 0.5), reported that they would repeat the program if given the opportunity (mean ± SD: 3.6 ± 0.5), and would recommend the program to family and friends (mean ± SD: 3.7 ± 0.5). For Cohort 3, the satisfaction ratings were similar to Cohorts 1 and 2 (see Supplemental Figure 1).

Symptoms (Parent-Report Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL))

Parent report of symptoms on the three CBCL subscales of interest (see Methods) showed a significant effect of time (F(1,17)=7.2, p = 0.016; see Supplemental Figure 2) and there was no significant effect of CBCL subscale or CBCL subscale × Time interaction (all p > 0.08). Post-hoc tests revealed that parent report of Anxious/Depressed symptoms decreased from baseline (M = 55.8, SD = 1.4) to post-intervention (M = 52.7, SD = 1.0; t(17) = 2.3, p = 0.03). Parent report of Social Problems also decreased from baseline (M = 57.2, SD = 1.9) to post-intervention (M = 53.6, SD = 0.9; t(17) = 2.1, p = 0.049). There was no significant change in parent-reported Withdrawn/Depressed symptoms following the intervention (t(17) = 0.47, p = 0.65).

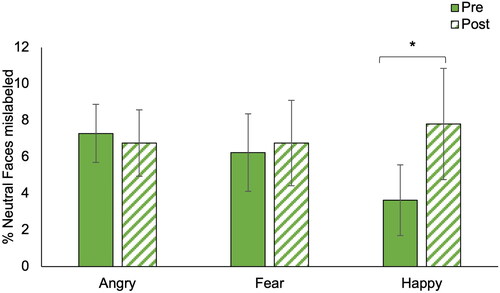

Figure 2. Following the intervention, participants were more likely to label neutral faces as happy (baseline: happy: 3.6% ± 1.9%; post-intervention: happy: 7.8% ± 3.0%, F(1,15)=5.5, p = 0.034), but there was no significant pre-post change in rates of labeling neutral faces as fearful or angry. *p < .05.

Emotion Recognition

Following the intervention, participants were more likely to label neutral faces as happy (baseline: 3.6% ± 1.9%; post-intervention: 7.8% ± 3.0%, F(1,15) = 5.5, p = 0.034; ). There was no change in rates of labeling neutral faces as fearful or angry (p > 0.05).

Also, exploratory analyses revealed a significant Time by Emotion interaction for emotion labeling accuracy, F(2,13) = 3.6, p = 0.04, and a significant Time by Intensity interaction (F(3,12) = 3.1, p = 0.04), but no main effect of time (F(1,14) = 0.004, p = 0.95; see Supplementary Figure 3). However, follow-up simple effects tests comparing baseline to post-intervention accuracy for each emotion and intensity category were not significant.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This pilot study showed that a brief, group-based, resilience-focused program delivered to at-risk adolescents growing up in an economically and socially disadvantaged community is feasible and acceptable to participants. In addition, we found preliminary evidence that the intervention is associated with reductions in transdiagnostic symptoms of psychopathology and may enhance a bias towards positive social attributions.

Targeting transdiagnostic risk

We found evidence for post-intervention reductions in subthreshold levels of negative affect and social impairment. These changes could, in theory, be protective of the mental health of these adolescents, reducing the level of risk for the future development of psychiatric illness, given the risk associated with the presence of such subthreshold symptoms (Balázs et al., Citation2013; Philipp et al., Citation2018; Rai et al., Citation2010). Screening for non-specific symptoms of psychopathology has been previously recognized as a way to identify children who may not need immediate treatment but could benefit from learning resilience-promoting skills (Ani & Garralda, Citation2005). This study shows that this strategy is feasible to implement through a community-based pediatrics practice and that many families welcome the opportunity to participate in this type of program.

When considering how to conduct this type of program, it is clearly important to consider the barriers to implementing such prevention-oriented programs in communities affected by high poverty rates and structural inequality, including inaccurate beliefs about such communities such as: (1) there is little interest or ability to participate in these types of interventions in these communities, or (2) these types of programs will have limited benefit given the substantial structural issues these families face. Our initial findings are not consistent with these assumptions. This type of program development is in line with the World Health Organization’s emphasis on developing and testing scalable psychosocial interventions in communities affected by adversity, since these communities often have fewer clinical services available, more barriers to accessing services, and greater clinical need, compared to those with greater resources (World Health Organization, Citation2017).

Adapting to the cultural and societal context

The program evaluated in this study was tailored to the cultural context of the participants; commonly held Latinx community values informed the delivery of the material, and there was at least one bilingual/bicultural group facilitator, who conducted the parent sessions in Spanish. Prior work suggests that these types of adaptations increase efficacy; one meta-analysis demonstrated that culturally-adapted mental health interventions are four times more effective than those which are not adapted (Griner & Smith, Citation2006). Also, conducting the parent sessions in the native language of the participants likely improved uptake of the material, as shown in prior studies (Griner & Smith, Citation2006).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the intervention was delivered virtually (via video teleconferencing), since in-person sessions were not possible due to pandemic-related restrictions. The virtually-delivered intervention was as well-received as the in-person version (as reflected by the satisfaction ratings) and was feasible in this population. However, more work is needed to directly compare the in-person and virtual delivery approaches.

Emotion attribution biases

In this study we also collected a task-based measurement of emotion recognition, to investigate one hypothesized mechanism of the intervention: modification of biases to attribute negative or positive valence to a neutral social stimulus. We predicted that the intervention would be associated with decreases in negative, and increases in positive, social attribution biases. We found that the adolescent participants of this study were significantly more likely to misattribute positively-valenced emotion (i.e., happiness) to neutral faces following the intervention, compared to baseline. This change may reflect an enhanced ability to generate positive affect. In contrast, we did not observe a reduction in the bias to attribute negative affect (i.e., anger, fear) to neutral faces following the intervention. Our finding of an enhanced positive social attribution bias following the intervention may provide clues about the underlying mechanisms of the program given prior evidence suggesting that increasing positive affect may improve psychiatric outcomes and overall emotional resilience (Craske et al., Citation2019; Seligman et al., Citation2006). However, additional larger, controlled studies will be needed to definitively link such hypothesized mechanisms to any clinical effects of the intervention.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that are primarily related to its intended function as a pilot program. The samples were small and a single-arm design was used; thus no inferences about the efficacy of the program can be made based on the current results. Also, the instrument used to screen for subthreshold symptoms and determine eligibility was the same behavioral health screening instrument used by the pediatrics clinic where recruitment for the study took place. Using a screener that was an existing component of routine clinical care was a central feature of the program’s design and contributed to its feasibility. However, because the clinic chose to switch to a different screening instrument during the course of the study, all of the participants of the three cohorts were not screened using the same instrument. However, despite this change, the clinical characteristics and demographics of the cohorts were similar.

Although 29% of those who were eligible agreed to participate in the program, approximately 43% of eligible families could not be reached via phone or email following screening and 27% of eligible families declined to participate. Many eligible families had multiple children and had several jobs, thus participating in the program may have been challenging due to competing demands on their time. In addition, enrollment in Cohort 3 was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a large impact on the town where this study was conducted (Sequist, Citation2020). In the future, having staff available in the clinic to follow up with families after screening or connecting with parents through the school system may increase program participation. Additionally, “parent ambassadors” who previously completed the program could assist with recruiting eligible families.

Future directions

A randomized-controlled trial with longitudinal follow-up is needed to determine whether the program has specific, beneficial effects on subthreshold symptoms of psychopathology and positive social attribution biases. Such a trial could also assess the efficacy of this program, and its cost-effectiveness, with respect to prevention of long-term negative outcomes including psychiatric diagnoses and treatment, involvement in the juvenile justice system, and declines in academic, occupational, or social functioning.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the critical assistance of Rebecca Lambert, M.D., Sara Nelson M.D., Rebecca Cronin, M.D., Nancy Lundy, Ed.D., Mary Lyons-Hunter, Psy.D., Kelsey Han, M.D., Francisco Palacios Bustamante, M.D., Maria Luisa Victoria, Ph.D., and Leah Namey, M.P.H. in the design and execution of this project.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Clauss, Ms. Bhiku, Dr. Burke, Ms. Pimentel-Diaz, Dr. DeTore, Ms. Zapetis, Ms. Zvonar, Ms. Kritikos, Dr. Canenguez, Dr. Cather, and Dr. Holt report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (2009). The achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development. Findings, theory, and applications. University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

- Addington, J., Devoe, D. J., & Santesteban-Echarri, O. (2019). Multidisciplinary treatment for individuals at clinical high risk of developing psychosis. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-019-0164-6

- Ani, C., & Garralda, E. (2005). Developing primary mental healthcare for children and adolescents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18(4), 440–444. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000172065.86272.c7

- Balázs, J., Miklósi, M., Keresztény, A., Hoven, C. W., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Apter, A., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Cosman, D., Cotter, P., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J.-P., Keeley, H., Marusic, D., Postuvan, V., Resch, F., … Wasserman, D. (2013). Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: Psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk: Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(6), 670–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12016

- Beadel, J. R., Mathews, A., & Teachman, B. A. (2016). Cognitive bias modification to enhance resilience to a panic challenge. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(6), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9791-z

- Carpenter, J. S., Scott, J., Iorfino, F., Crouse, J. J., Ho, N., Hermens, D. F., Cross, S. P. M., Naismith, S. L., Guastella, A. J., Scott, E. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2022). Predicting the emergence of full-threshold bipolar I, bipolar II and psychotic disorders in young people presenting to early intervention mental health services. Psychological Medicine, 52(10), 1990–2000. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003840

- Craske, M. G., Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Treanor, M., Dour, H., & Rosenfield, D. (2019). Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000396

- Dozois, D. J. A., Seeds, P. M., & Collins, K. A. (2009). Transdiagnostic approaches to the prevention of depression and anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(1), 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.23.1.44

- Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., Nakamura, B. J., Chorpita, B. F., Higa-McMillan, C. K., & Weisz, J. R. (2010). Concurrent validity of the child behavior checklist DSM-oriented scales: Correspondence with DSM diagnoses and comparison to syndrome scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9174-9

- Eisenhower, A., Suyemoto, K., Lucchese, F., & Canenguez, K. (2014). “Which box should I check?”: Examining standard check box approaches to measuring race and ethnicity. Health Services Research, 49(3), 1034–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12132

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

- Griner, D., & Smith, T. B. (2006). Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 43(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531

- Hanssen, M., Bak, M., Bijl, R., Vollebergh, W., & Os, J. (2005). The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 2), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29611

- Hofstra, M. B., Van Der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002). Child and adolescent problems predict DSM-IV disorders in adulthood: A 14-year follow-up of a Dutch epidemiological sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200202000-00012

- Hollon, S. D., Muñoz, R. F., Barlow, D. H., Beardslee, W. R., Bell, C. C., Bernal, G., Clarke, G. N., Franciosi, L. P., Kazdin, A. E., Kohn, L., Linehan, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., Miklowitz, D. J., Persons, J. B., Niederehe, G., & Sommers, D. (2002). Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: Promoting innovation and increasing access. Biological Psychiatry, 52(6), 610–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01384-7

- Horowitz, J. L., & Garber, J. (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401

- Jellinek, M. S., Murphy, J. M., Robinson, J., Feins, A., Lamb, S., & Fenton, T. (1988). Pediatric Symptom Checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. The Journal of Pediatrics, 112(2), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80056-8

- Jutte, D. P., Burgos, A., Mendoza, F., Ford, C. B., & Huffman, L. C. (2003). Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist in a low-income, Mexican American population. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 157(12), 1169–1176. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1169

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Dell.

- Kelleher, I., Connor, D., Clarke, M. C., Devlin, N., Harley, M., & Cannon, M. (2012). Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1857–1863. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002960

- Kelleher, I., Keeley, H., Corcoran, P., Lynch, F., Fitzpatrick, C., Devlin, N., Molloy, C., Roddy, S., Clarke, M. C., Harley, M., Arseneault, L., Wasserman, C., Carli, V., Sarchiapone, M., Hoven, C., Wasserman, D., & Cannon, M. (2012). Clinicopathological significance of psychotic experiences in non-psychotic young people: Evidence from four population-based studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 201(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101543

- Leppänen, J. M., Milders, M., Bell, J. S., Terriere, E., & Hietanen, J. K. (2004). Depression biases the recognition of emotionally neutral faces. Psychiatry Research, 128(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.020

- Liang, J., Matheson, B. E., & Douglas, J. M. (2016). Mental health diagnostic considerations in racial/ethnic minority youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 1926–1940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0351-z

- Mandelli, L., Petrelli, C., & Serretti, A. (2015). The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 30(6), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007

- Martinez, C. R., & Eddy, J. M. (2005). Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 841–851.

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Center for Community Health Improvement (2012). Chelsea community health: Needs assessment and strategic planning report. Massachusetts General Hospital, Center for Community Health Improvement.

- McGorry, P. D., Hartmann, J. A., Spooner, R., & Nelson, B. (2018). Beyond the “at risk mental state” concept: Transitioning to transdiagnostic psychiatry. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20514

- McLaughlin, K. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Mennin, D. S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(9), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003

- Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

- Osborne, K. J., Willroth, E. C., DeVylder, J. E., Mittal, V. A., & Hilimire, M. R. (2017). Investigating the association between emotion regulation and distress in adults with psychotic-like experiences. Psychiatry Research, 256, 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.011

- Patrick, D., Murray, T., Bigby, J., & Auerbach, J. (2007). Regional health status indicators Boston Massachusetts. Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

- Philipp, J., Zeiler, M., Waldherr, K., Truttmann, S., Dür, W., Karwautz, A. F. K., & Wagner, G. (2018). Prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems and subthreshold psychiatric disorders in Austrian adolescents and the need for prevention. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(12), 1325–1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1586-y

- Pinkham, A. E., Brensinger, C., Kohler, C., Gur, R. E., & Gur, R. C. (2011). Actively paranoid patients with schizophrenia over attribute anger to neutral faces. Schizophrenia Research, 125(2-3), 174–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.006

- Poulton, R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Cannon, M., Murray, R., & Harrington, H. (2000). Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: A 15-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(11), 1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1053

- Rai, D., Skapinakis, P., Wiles, N., Lewis, G., & Araya, R. (2010). Common mental disorders, subthreshold symptoms and disability: Longitudinal study. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 197(5), 411–412. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.079244

- Reeck, C., Ames, D. R., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The social regulation of emotion: An integrative, cross-disciplinary model. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.003

- Reiter, A. M. F., Atiya, N., Berwian, I. M., Huys, Q. J. M., & Huys, Q. (2021). Neuro-cognitive processes as mediators of psychological treatment effects. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 38, 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.007

- Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7), S35-S39. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x

- Seligman, M. E., P., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. The American Psychologist, 61(8), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774

- Sequist, T. D. (2020). The disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on communities of color. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 1(4). https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0370

- Shah, J. L., Scott, J., McGorry, P. D., Cross, S. P. M., Keshavan, M. S., Nelson, B., Wood, S. J., Marwaha, S., Yung, A. R., Scott, E. M., Öngür, D., Conus, P., Henry, C., & Hickie, I. B. (2020). Transdiagnostic clinical staging in youth mental health: A first international consensus statement. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 19(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20745

- Smith, M. (2004). Parental mental health: Disruptions to parenting and outcomes for children. Child & Family Social Work, 9(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00312.x

- Stilo, S. A., Gayer-Anderson, C., Beards, S., Hubbard, K., Onyejiaka, A., Keraite, A., Borges, S., Mondelli, V., Dazzan, P., Pariante, C., Di Forti, M., Murray, R. M., & Morgan, C. (2017). Further evidence of a cumulative effect of social disadvantage on risk of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 47(5), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002993

- Thompson, E., Millman, Z. B., Okuzawa, N., Mittal, V., DeVylder, J., Skadberg, T., Buchanan, R. W., Reeves, G. M., & Schiffman, J. (2015). Evidence-based early interventions for individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: A review of treatment components. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(5), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000287

- Uchida, M., Fitzgerald, M., Lin, K., Carrellas, N., Woodworth, H., & Biederman, J. (2017). Can subsyndromal manifestations of major depression be identified in children at risk? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12660

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (2014–2018).

- van Os, J., & Reininghaus, U. (2016). Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20310

- Wiggins, J. L., Adleman, N. E., Kim, P., Oakes, A. H., Hsu, D., Reynolds, R. C., Chen, G., Pine, D. S., Brotman, M. A., & Leibenluft, E. (2016). Developmental differences in the neural mechanisms of facial emotion labeling. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(1), 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv101

- Wiggins, J. L., Brotman, M. A., Adleman, N. E., Kim, P., Wambach, C. G., Reynolds, R. C., Chen, G., Towbin, K., Pine, D. S., & Leibenluft, E. (2017). Neural markers in pediatric bipolar disorder and familial risk for bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.009

- World Health Organization (2017). Scalable psychological interventions for people in communities affected by adversity: A new area of mental health and psychosocial work at WHO. WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254581/WHO-MSD-MER-17.1-eng.pdf

- Yoon, K. L., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2008). Interpreting neutral faces as threatening is a default mode for socially anxious individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 680–685.